Modelling Goals for Complex Problems: An Approach on the SofIA

Methodology

F. Gracia-Ahufinger , Javier J. Guti

´

errez , J. A. Garc

´

ıa-Garc

´

ıa and Mar

´

ıa-Jos

´

e Escalona

University of Seville, Computer Engineering School, Seville, Spain

Keywords:

Model-Driven Software Engineering, Cynefin, Scrum, Complex Problems, Goal Modelling, Requirements

Engineering, Decision Making.

Abstract:

Complex Problem Solving (CPS) is a paradigm in modern software development. Goal modelling for ad-

dressing complex requirements is a challenge that SofIA, Software Methodology for Industrial Application,

meta-model leverages in the Cynefin framework to define complexity by employing Scrum to manage iterative

development. The key contributions of this article are to introduce new meta-model elements to facilitate goal-

orientated modelling within the SofIA framework, establish relationships between goals and various artefacts

developed during the construction of Information Systems and a practical application of the extended SofIA

meta-model to demonstrate through a case study, showing its effectiveness in a real-world project. The paper

provides an example of integrating Cynefin and Scrum within a Model-Driven (Software) Engineering (MDE)

context to tackle CPS. The extended SofIA approach aims to improve decision-making and project success by

defining clear objectives and iteratively evaluating their adequacy and impact on overall system development.

1 INTRODUCTION

MDE is a software development methodology that

evolved as a shift from object-orientated to model

engineering paradigms, describing a software devel-

opment approach in which developers represent sys-

tems as models that conform to meta-models, (Liddle,

2010), to then use model transformations to manipu-

late them to obtain additional artefacts. For example,

it is possible to create analysis, design, and test arte-

facts such as navigation models or screen prototypes

based on functional requirements.

SofIA is a Computer-Aided Software Engineer-

ing (CASE) tool that provides maximum flexibility

when modelling functionality, data, or prototypes be-

cause it can use any given model to generate other

models. It achieves its objectives by supporting bidi-

rectional transformations and guaranteeing traceabil-

ity between all models (Mar

´

ıa-Jos

´

e Escalona et al.,

2023).

In the software engineering field, there are vari-

ous definitions of requirement engineering. One of

the first, which still prevails today, was provided by

(Ross and Schoman, 1977) in 1977: “requirements

definition is a careful assessment of the requirements

that a system is to fulfil”. Requirements must clar-

ify why a system is desirable according to present re-

quirements, which could indicate an internal opera-

tion or an external effect. It has to respond to which

system properties are suitable in this situation, and it

has to specify how the system will be created. Soft-

ware Engineering Requirements can be categorised as

CPS as part of the complex project management do-

main, (Ahern et al., 2014).

CPS refers to the ability to solve complex and am-

biguous problems that often require creative and in-

novative solutions. It involves identifying the root

cause of a problem, analysing different variables and

factors, developing and evaluating possible solutions,

and selecting the best course of action (Lteif, 2024).

However, in software development, it has been

necessary to address complex problems for which

there is no list of requirements, precisely because of

their complex nature. Is it possible to use MDE in the

development of a system in a complex domain? The

main difficulty is that, in a complex system, correctly

implementing a set of functional requirements does

not guarantee the success of the system.

This paper takes the MDE approach SofIA and

extends it to incorporate a definition of objectives to

address complex problems. Through objectives and

their relationship to requirements, the new SofIA ap-

proach can answer questions such as: What is the goal

of the next iteration? How do we know if the require-

ments are adequate? Is the project succeeding?

In the context of CPS, requirements can be clas-

sified or decomposed into the simplest requirements.

David Snowden worked in a conceptual framework

Gracia-Ahufinger, F., Gutiérrez, J. J., García-García, J. A. and Escalona, M.-J.

Modelling Goals for Complex Problems: An Approach on the SofIA Methodology.

DOI: 10.5220/0013713200003985

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2025), pages 173-180

ISBN: 978-989-758-772-6; ISSN: 2184-3252

Proceedings Copyright © 2026 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

173

to aid decision-making, Cynefin (Snowden, 2010),

which recognises the causal differences that exist be-

tween different types of systems and proposes new

approaches to decision-making in complex social en-

vironments and new mechanisms to understand the

levels of complexity as decisions are made (O’Connor

and Lepmets, 2015). Its extended use in the last 30

years to support decision-making in a complex con-

text has motivated the authors of this article to use it

as part of the research.

The original contributions of this paper are de-

scribed below:

1. A redefinition of Scrum cycle to integrate CPS.

2. An extension of SofIA meta-models with goals.

3. A relationship of the goals with the possible arte-

facts to be developed during the construction of

an information system.

4. A case study of applying goals to real projects.

5. An example of how to extend SofIA in CPS, re-

lating Cynefin and Scrum in a context of model-

driven engineering.

The structure of this paper is; Section 2 introduces

Scrum and Cynefin, and establish the relationships be-

tween both used in the article, and how the Prod-

uct Goal is applied to Scrum, Section 3 introduces

how Scrum and Cynefin can be integrated to approach

CPS, and presents the SofIA meta-model set, Section

4 describes a new meta-model that extends SofIA for

goal modelling, Section 5 presents an example of us-

ing the goals meta-model, with SofIA itself, finally,

Section 6 presents conclusions and future work.

2 RELATED WORKS

2.1 Complexity in Software

Development

Complexity is a term used all over the place. How-

ever, in the last 20 years, the use of this term has been

linked to the popularisation of Cynefin framework, a

heuristic tool to understand and make sense of situa-

tions or problems in order to make decisions (Snow-

den, 2002).

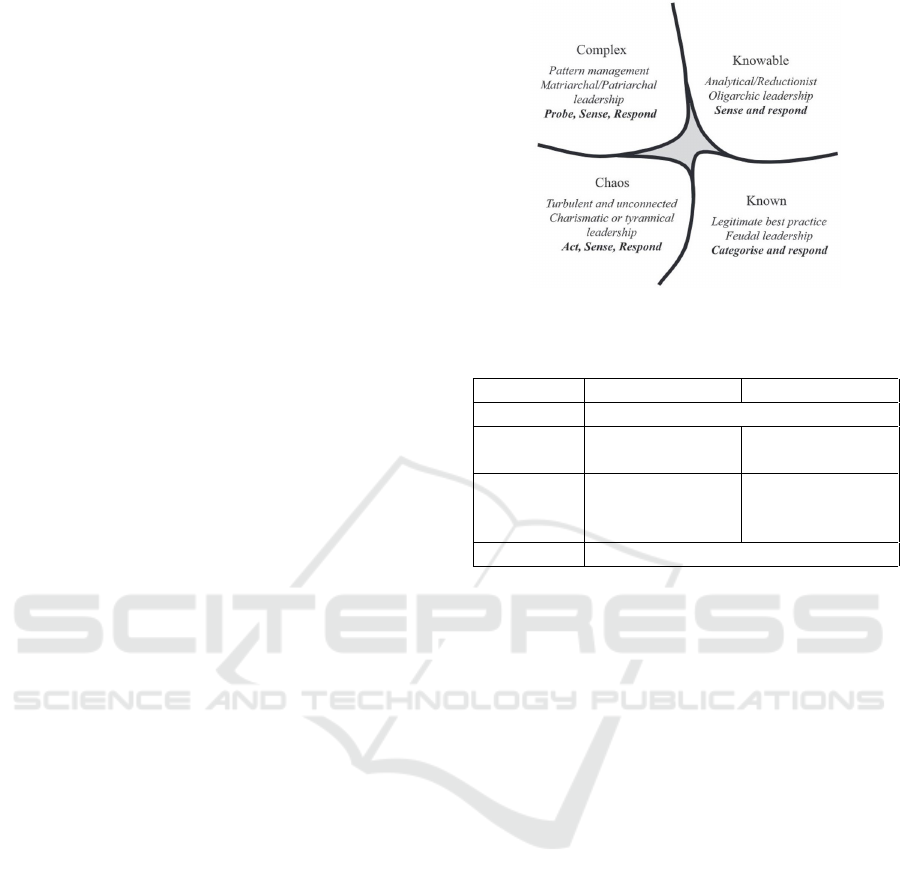

It identifies four different contexts for inference

and decision, plus an additional context symbolised as

the grey one in Figure 1. These contexts do not pro-

vide a hard categorisation. The boundaries are soft

and the contexts close to these have characteristics

drawn from both sides (French, 2015). For the sake

of simplicity, we will focus only on the Known and

Complex contexts.

Figure 1: Cynefin, decision making framework.

Table 1: Known vs. Complex domain.

Known Complex

Sense Search for cause-effect relationships

Categorize Organize a set of

actions

Not used

Probe Not used Introduce a

stimulus into the

system

Respond Define a course of action

Known context is focused on following the best

practices because all levels of knowledge are clear

and there is no margin for error, in fact, the restric-

tions here are strict because the best practices have

already been tested and currently reach the goals for

which they were created. The causes and effects here

are known and we should use known best practices

for resolution (Snowden, 2002) (Snowden and Boone,

2007).

Complex context is unordered and searches for re-

sponses based on emerging patterns (Snowden and

Boone, 2007). It is characterised by unpredictability,

with complex relationships, ”relying on expert opin-

ions based on historically stable patterns of mean-

ing will insufficiently prepare us to recognise and

act upon unexpected patterns” (Kurtz and Snowden,

2003).

Cynefin prescribes that you should Probe, Sense

and Respond in order to resolve a complex problem.

To Probe means to introduce invasive changes to the

system to produce new data. So, the problem solving

approach dictated by Cynefin is actually changing the

way you do things now (Probe) to see what happens

(Sense) and then Respond appropriately (O’Connor

and Lepmets, 2015). Table 1 summarises how to per-

form the actions defined in Cynefin in a Known do-

main and a Complex domain.

Let us see two examples of possible problem clas-

sification in Cynefin’s domains:

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

174

• Known context: e-Commerce development has no

complexity because there is a series of metaphors,

design patterns, and processes that have become

standard in this type of system.

• Complex context: Autonomous driving initially

was faced as looking for an algorithm that would

process a finite number of possible scenarios, and

now artificial intelligence, nurtured by as much

information as possible so that this intelligence

can learn to drive and make the best decision. Ei-

ther way, no final standardised solution has been

found yet.

How can a complex problem be solved in the in-

formation systems domain?

2.2 Scrum for Complex Problems

”Scrum is a lightweight framework that helps people,

teams and organisations generate value through adap-

tive solutions for complex problems” (Schwaber and

Sutherland, 2020), it is not a prescriptive process, it

needs adaptation. Choosing an appropriate software

development process is a complex and difficult task,

compounded by the fact that all process models re-

quire a certain amount of adaptation to fit the business

environment of any specific organisation in which the

model is to be implemented (Hasan and Kazlauskas,

2009) (O’Connor and Lepmets, 2015). It is important

to understand a problem domain to define this pro-

cess.

Scrum approaches CPS through empirical man-

agement using transparent inspection and adaptation

cycles. Scrum proposes work cycles of one month or

less, called Sprint, to create a product increment to

obtain information, for example, to identify some of

the constraints or patterns of the complex problem,

search for relations as seen in Table 1. At the end

of a Sprint, everyone involved in the Sprint works to

inspect the outcomes of the product increment and de-

termine a Respond for further Sprint (Kadenic et al.,

2023) (Saltz and Heckman, 2020).

Scrum’s Product Goal describes a future state of

the product that can serve as an objective for the

Scrum Team, therefore delivering the Sprint Goal, to

plan. The Product Goal is stored in a Scrum artefact

called the Product Backlog, which contains the infor-

mation needed to define ”what” will meet the Product

Goal. The Sprint Goal communicates why the next

Sprint is valuable to stakeholders.

2.3 Goal Definition in Scrum

As part of the related work, we have searched for ex-

amples and proposals on how to define the Product

Figure 2: Vanity metric.

Figure 3: Implement functionality.

Goal and the Sprint Goal in Scrum. For this pur-

pose, we have made a search for the concept ”Prod-

uct Goal” between May and June 2023. The results

of this search show that there appear to be no articles

dedicated to this specific Scrum point despite its im-

portance in Scrum.

Taking into account these results, we have con-

ducted a search for examples of Product Goal pub-

lished in articles of the years 2023, 2022, and 2021.

The reason for selecting these three years is that the

latest version of the Scrum Guide was published at the

end of 2020 and introduced changes in the definition

and management of the Product Goal and the Sprint

Goal. In total, we found 28 articles, but only 2 of them

contain examples. The following are the examples of

Product Goal found.

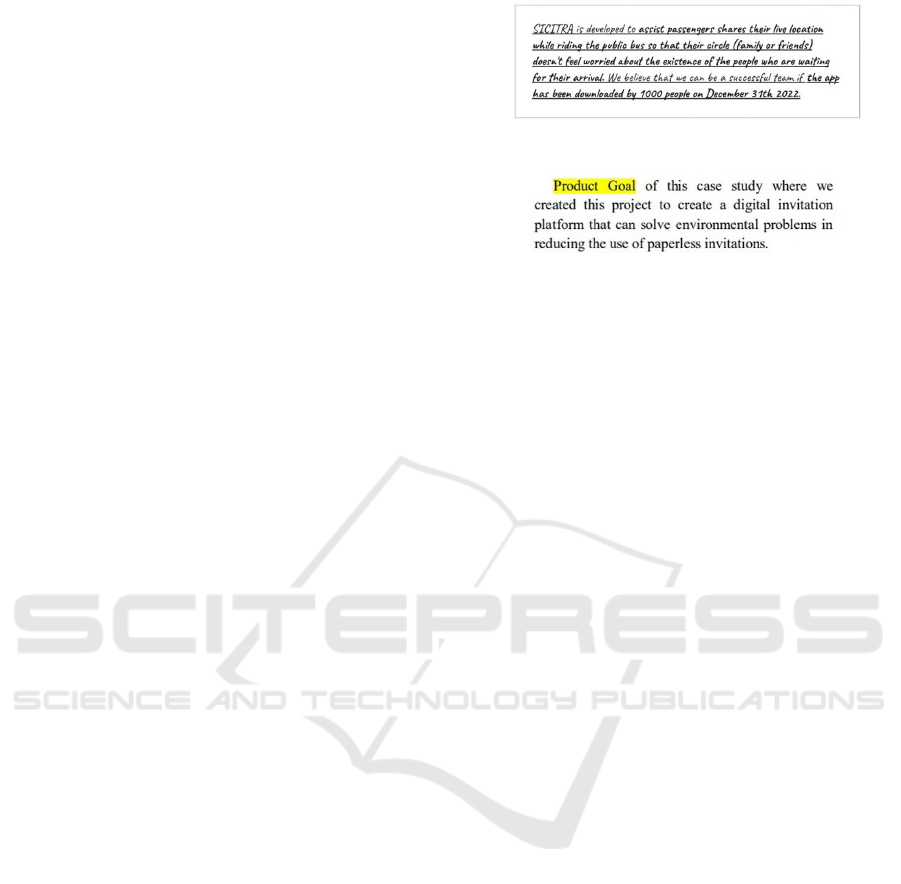

Figures 2 and 3 show examples of a Product Goal.

The first one, (Rachmawati et al., 2023), falls un-

der what is known as the vanity metric, which shows

attractive numbers, but does not fully reflect real

progress. They are classified as non-actionable be-

cause they are not useful for decision making. The

number of downloads is not an indicator of the usage

or usefulness of the system. The second, (Hidayah

et al., 2022), falls within the functional goal, in which

the goal is simply to implement a functionality with-

out taking into account any criterion or measure that

determines whether this functionality is being used or

satisfies the problems and needs of its users.

3 SCRUM AND CYNEFIN TO

APPROACH CPS

The work cycle proposed by Scrum, Figure 4, is not

adequate to solve a complex problem nor does it ad-

equately define Scrum according to the definitions of

Scrum itself seen in the previous Section. First of all,

it is focused on Scrum events and roles, when the im-

portant thing is to identify the mechanisms to reduce

complexity and detect cause-effect relationships that

Modelling Goals for Complex Problems: An Approach on the SofIA Methodology

175

Figure 4: Scrum development process.

Figure 5: Loop for CPS with Scrum.

may exist and move the problem to a Known domain

as seen in Cynefin in the previous Section.

Secondly, stakeholder participation is relegated to

the beginning and end of the cycle. However, in

a complex problem and in cycles of inspection and

adaptation, the constant participation of stakeholders

is essential to understand what is happening and if

progress is being made in the right direction, in par-

ticular, the Sense element seen above.

In addition, Scrum Product Goal is not discrete,

but continuous, since it is possible to get closer to it

as cause-effect relationships are discovered, and the

problem moves to a Known domain as we have al-

ready seen in the previous Section.

For this reason, in order to apply Scrum cycle, to

the resolution of a complex problem, as indicated by

the Scrum definition itself, a redefinition of the Scrum

cycle is proposed in Figure 5. The purpose is to intro-

duce a series of stimuli, Probe, into the system to see

to what extent these stimuli allow to reach an objec-

tive, Sense, and, based on this analysis, to establish a

new action plan, Respond.

It is possible to relate the triplet of Probe, Sense

and Respond to the Scrum way of working. Table 2

shows the relationship between the strategy proposed

by Cynefin for complex problems and the elements of

the lightweight Scrum framework.

Table 2: Relationship of Cynefin elements with Scrum ele-

ments.

Cynefin Scrum

Probe Sprint Goal, Sprint Backlog

Sense Product Goal, Sprint Goal, Increment

Respond Sprint Review

Figure 6: Meta-model for SofIA.

Probe in Scrum is done through the Sprint, since

all the work in Scrum is done within a Sprint. Each

of them contains the Sprint Goal and the Sprint Back-

log. The Sense part is performed by developing a fea-

ture, Increment, that is available to users and collect-

ing user feedback. At the end of the Sprint, an event is

held to evaluate the progress of the Product Backlog

and prepare the Respond by preparing the next Sprint,

Sprint Review.

How can MDE work with goals compatible with

the Product Goal and the Sprint Goal definition in

Scrum?

4 A META-MODEL FOR GOALS

4.1 Introducing SofIA

SofIA is a MDE proposal for models and artefacts that

is accompanied by a CASE tool of the same name

(Mar

´

ıa-Jos

´

e Escalona et al., 2023). SofIA was de-

signed using the four-level architecture (Gonzalez-

Perez and Henderson-Sellers, 2008), which has tradi-

tionally been used to establish a relationship between

models and meta-models, Figure 6. In this architec-

ture each level defines de meta.models and models

used by the next level.

In Section 2, we have seen that there are no ade-

quate sources that offer references on how to define

the Product Goal and the Sprint Goal. The main

sources come from techniques used by practitioners

without the support of research papers. In addition,

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

176

Figure 7: Meta-model for Goals.

papers on requirements in the development of re-

search systems use goals as an additional requirement

definition technique, not with the complex domain ap-

proach defined in Cynefin.

We have chosen to define goals as quantitative at-

tributes due to the lack of uniformity or standard and

widely used criteria. We have defined the following

characteristics to define goals in SofIA:

1. The goal must be quantifiable in a numerical way,

it must be a metric.

2. The goal must have a minimum range and a max-

imum range that indicate the zone of success.

3. The goal can be an aggregation of other goals.

In this way, the goals are not linked to any spe-

cific technique. Any technique that allows meeting

the three previous characteristics can be applied to the

proposal defined in this Section, and teams can adapt

this work to their techniques. In addition, this way of

defining goals fits with the Scrum definitions of Prod-

uct Goal and Sprint Goal.

4.2 Meta-Model Architecture M2-Level

At the M2-level, SofIA defines five meta-models that

represent the following SofIA concepts and their re-

lationships: Conceptual, Functional Requirements,

Prototype, Testing, and Interaction Flow. SofIA

also defines an additional Traceability meta-model

(Escalona et al., 2022), establishing conceptual trace-

ability connections between the different elements

of the meta-models. The Traceability meta-model

implements bidirectional formal transformations that

help to maintain the consistency between models.

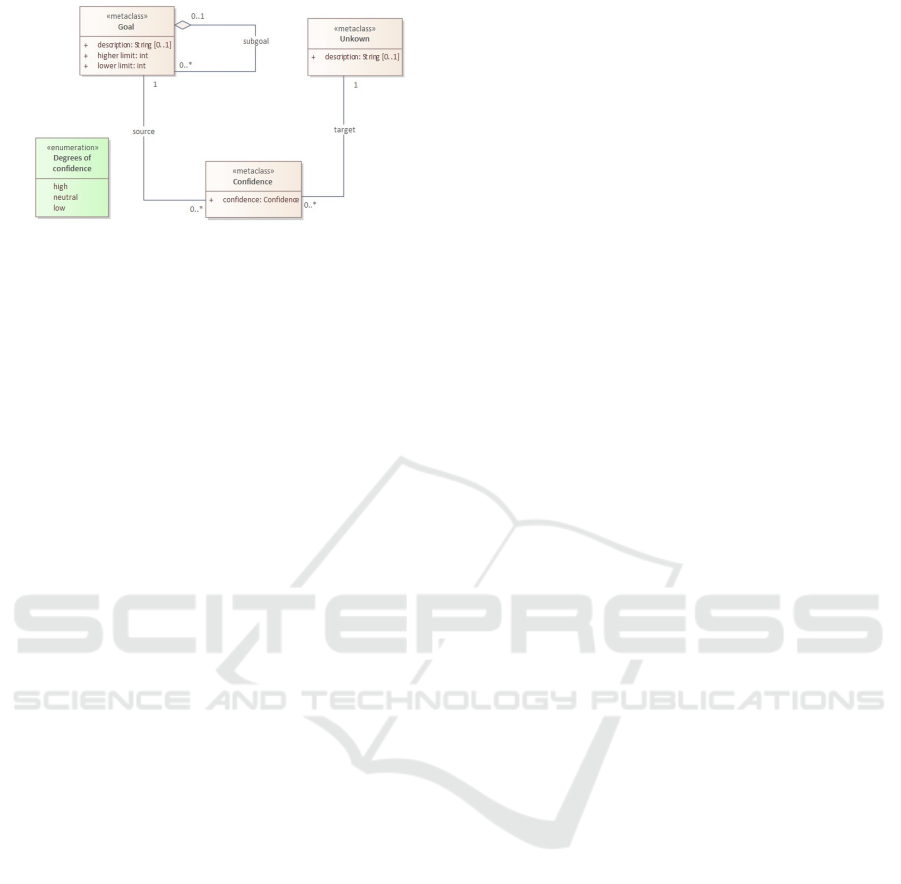

Furthermore, it defines 3 elements: Goal, Unknown

and Confidence, Figure 7.

Goal is the meta-model that models a goal as de-

fined in Section 2. A Goal can exists by itself without

the need to have sub-goals or be part of another Goal.

However, for more complex goals it is necessary to

decompose them into sub-goals.

One way to approach a complex problem is by

defining a goal and developing work periods that im-

plement ideas and evaluate how they affect the goals

set. In SofIA, one of these work periods is likely

to contain functional requirements, scenarios, screen

mock-ups, and tests taken from the various models it

defines.

In order to identify what can be done in one of

these work periods, the Unknown element has been

defined. An Unknown element is a package that stores

elements from other models based on a criterion. The

criterion related to an Unknown serves to define an as-

sumption or hypothesis of how to approach the Goal

related to the Unknown.

To create the Unknown elements, we use a free

buffet technique. As in a free buffet restaurant, de-

velopers take their plate, Unknown, and go through

all that is available, the different SofIA models, se-

lecting what they consider the most appetizing, what

will contribute the most to the goal. Therefore, an

Unknown will probably have part requirements, part

tests, screen mock-ups, and any other element defined

in the SofIA models.

It is possible and easy to identify which elements

are related to elements belonging to the same Un-

known using SofIA traceability elements. In this way,

it is easy to organise Unknown with all related ele-

ments even if they are from different models.

The last element is the Confidence association.

This association links a Goal element with the Un-

known elements by classifying the latter in a scale.

The criterion proposed by the meta-model is a scale

of three values: high, neutral, and low. This scale

is defined by the enumerated type ”Degree of confi-

dence” in Figure 7.

A value of high indicates that the team is very con-

fident that the elements of this Unknown element can

positively affect the Goal element. A value of low

indicates that the team is low confident that the el-

ements of this Unknown can have an impact on the

Goal. A value of neutral indicates that the team does

not know if the elements of this Unknown can affect

the Goal product, or believes that they will have no

effect.

This association is not mandatory, as it only makes

sense when the team raises several possible Unknown

elements. If the team, for example, works on devel-

oping only the Unknown of the next iteration, there is

no value in using this association.

4.3 Meta-Model Architecture M1-Level

For the Conceptual meta-model, at the M1-level,

a UML class diagram was incorporated, while for

Modelling Goals for Complex Problems: An Approach on the SofIA Methodology

177

the Functional Requirements meta-model a UML use

case model and one or more scenario models were

included. For the Prototypes meta-model a mock-ups

model was introduced and, the Interaction Flow Mod-

elling (IFM) meta-model incorporated an interaction

flow model using the IFM Language (Eisenbart et al.,

2015).

At this level, SofIA defines the different models of

the different artefacts defined in the M2-level meta-

model. For example, at this level, the requirements

models of a system in development are defined, such

as the model in Figure 7. These SofIA models provide

a partial view of the project, but the Goal elements are

common to the project and affect all elements that can

be modelled in SofIA.

However, when using Scrum definitions, you will

only have a single Goal element for the whole prod-

uct. This Goal element fulfils the Product Goal mis-

sion. This means that this Goal will be related to

all other artefacts in the system, since all the other

artefacts must be necessary to achieve this Goal, even

though they may contribute to the achievement of the

Goal to a greater or lesser extent, as we have already

seen with the definition of the Confidence association

in the previous Subsection.

Based on our experience with the case study, Sec-

tion 5, we have decided not to impose a specific syn-

tax, but to leave teams free to define their own syntax.

For example, a team working with Scrum will already

use its own tools to manage the Product Backlog, so

it is more appropriate for the modelling of Goal, Un-

known and Confidence elements to be adapted to the

tools and format they already use for their Product

Backlog, since the Product Goal is part of the Prod-

uct Backlog, than to ask the team to use a different

modelling tool and dump all their information into it.

Based on this experience, three examples of con-

crete syntax are proposed below.

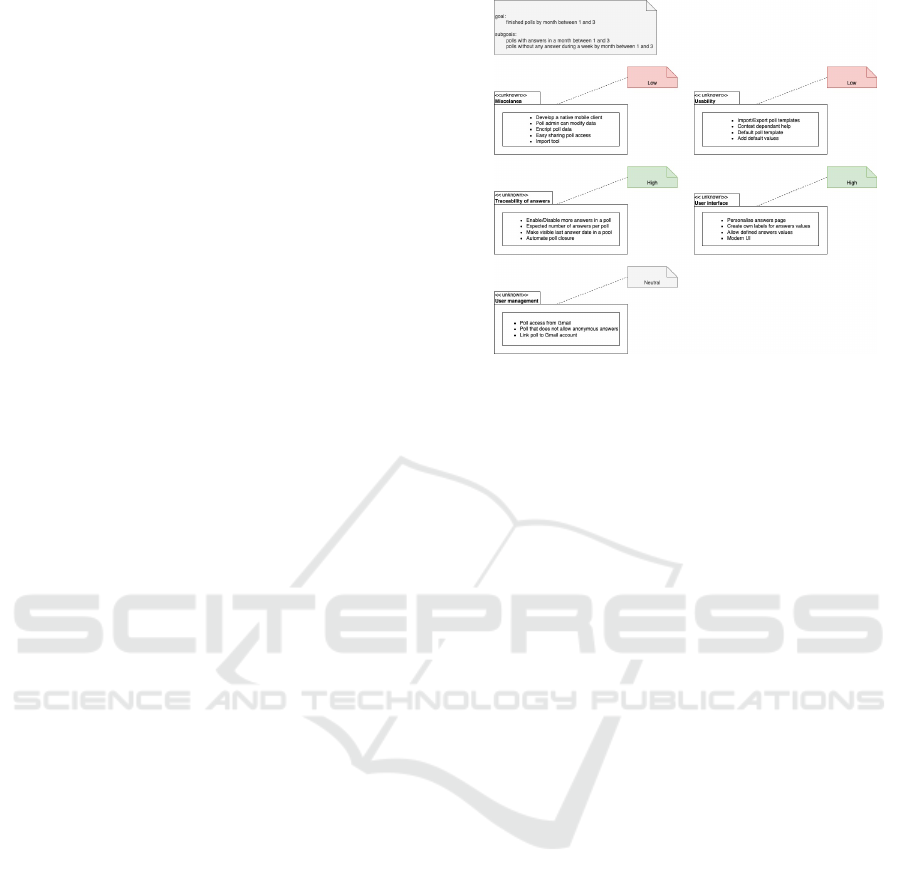

The first of these concrete syntaxes is called

Project Model. The purpose of this Project Model is

to represent the key Goals of the project, define the

Unknown elements, and establish their relationships

with the rest of the elements.

Alternatively, if you do not want to use a UML

use case notation to define Goal elements, you can

define the Goal as a comment as part of the models,

as shown in Figure 8.

4.4 Meta-Model Architecture M0-Level

At the M0-level, SofIA proposes two support tools;

Quality, allows us to check the compliance of specific

rules in the models, which will facilitate the use of the

second tool, Driver, who implements a set of transfor-

Figure 8: Example of Unknown.

mations that allows us to generate new models from

existing models by applying model-driven develop-

ment principles and techniques.

As already mentioned, the elements of the objec-

tive elements are not mandatory. Their use is recom-

mended for complex problems and they are manda-

tory if Scrum is applied to define the Product Goal

and the Sprint Goal. Therefore, the new Quality Tool

traceability rules for Goal elements should allow for

this freedom of choice:

R. 1: At least one Goal element must be related to at

least one Unknown element.

R. 2: Every Unknown element must be related to a

Goal element.

R.2 1: If project uses Scrum, an additional

third rule is added to contemplate the

elements defined in the Scrum guide.

R. 3: Every Unknown element must be related to two

Goals elements, one models the Product Back-

log and the other models the Sprint Backlog.

R. 4: All Goal elements that model the Sprint Back-

log must be related to the Goal that models the

Product Backlog.

SofIA’s Quality tool has been extended with sup-

port for the above four rules. This tool defines a clas-

sification of the rules, so it is necessary to comply

with some of the rules, but others are not manda-

tory but recommended. In the extension of Qual-

ity to incorporate the goals meta-model described in

this work, rules R1 and R2 have been implemented

as mandatory, and rules R3 and R4 as suggestions,

since it is not possible to know if you are working

with Scrum or not.

SofIA’s Driver tool objective is to generate new

models from existing models by applying transforma-

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

178

tions between models (Mens et al., 2006) (Czarnecki

and Helsen, 2003). SofIA goals model does not define

any transformation since it is not possible to create

new artefacts from Goal elements. The main reason is

that Goal elements belong to the problem domain, not

to the solution domain. For this reason, it is not possi-

ble to transform them into requirements, analysis, or

design artefacts, as is possible with other elements.

Let’s see how SofIA works in a practical case of

application.

5 CASE STUDY

5.1 SofIA Case Study

We have applied the extension of the SofIA model

for modelling Goal elements to SofIA itself, in order

to define objectives to help decide the next steps in

SofIA’s evolution.

SofIA is a research tool which exists since 2021

and is the evolution of a previous tool also based on

meta-models and models, which was born in 2004,

with the rise of model-driven engineering. The tool

prior to SofIA was used in several cases of knowledge

transfer with companies (Escalona and Arag

´

on, 2008)

(Escalona et al., 2007).

User satisfaction with SofIA is measured through

a satisfaction survey conducted with the Crew Radar

tool. This satisfaction survey evaluates five factors,

using a block of questions for each factor. The 5 fac-

tors are: added value, autonomy of use, integration

with other tools, flexibility, and detected errors. The

authors of SofIA define the goals based on the results

of the satisfaction survey in order to take into account

the satisfaction of the people who have used SofIA.

The main goal of SofIA in its development pro-

cess is that user satisfaction should be above 66% ac-

cording to the survey results. On a scale of 1 to 5

using the satisfaction survey questions, this means ob-

taining an average of 3.5 out of 5 on all results for all

survey questions. The current average, with 5 SofIA

users that have been working more than a year in the

final degree project, is 3.58 over 5.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presents a methodology for modeling

goals in complex software development environments

using the Cynefin framework, Scrum, and the SofIA

meta-model. It addresses key questions around itera-

tion goals, requirement adequacy, and project success

by introducing a goal-oriented modeling approach.

The original contribution (1.) has been achieved

by extending the SofIA meta-models of M2-level with

a meta-model for goals. In addition, this paper has

shown examples of M1-level models used as concrete

syntax to define goals with different notation accord-

ing to the characteristics of the project and the team.

One of the SofIA tools at M0-level, the Quality tool,

has also been modified to verify the rules to be fol-

lowed in the modelling of goals.

The original contribution (2.) is related to the def-

inition of complex domain. In a complex domain,

there are no clear cause-effect relationships, so the

implementation of system requirements is considered

as hypotheses that may or may not be validated by

customers and users. To model these hypotheses and

allow articulating team conversations and decisions,

the Unknown and Confidence elements have been in-

cluded in the Goals meta-model.

The original contribution (3.) has been fulfilled

with the SofIA case study. SofIA was used by several

students in their final projects degree

The original contribution (4.) has been fulfilled

by mapping the elements proposed by Cynefin in the

complex domain and the elements defined by Scrum.

This mapping has allowed us to apply the Scrum ele-

ments in the case study.

The original contribution (5.) has been shown in

Section 5.

The use of Scrum can help to start working with

goals, but it can also impose limitations when work-

ing with goals. For example, a limitation of Scrum

is that there can only be a single Product Goal, so it

is not very useful to link with stakeholders, since that

goal must satisfy all of them.

However, the meta-model presented in this paper

is capable of working in a more flexible goal envi-

ronment. The SofIA meta-model already contem-

plates the modelling of stakeholders, and the mod-

elled meta-goal that has been used as a base contem-

plates basic associations that could be established to

relate these stakeholders with the goals modelled in

this work.

In this paper, we have presented a meta-model,

tools, and case study to manage uncertainty in a soft-

ware development project. However, by the very na-

ture of this uncertainty, there are different ways of

working, and it is not possible or convenient to offer

a closed and rigid process. This is also aligned with

Scrum as this lightweight framework leaves a great

deal of freedom in the choice of techniques and prac-

tices in its application.

This has been seen, for example, in the case stud-

ies in which different techniques that the teams were

already using have been adapted to implement the

Modelling Goals for Complex Problems: An Approach on the SofIA Methodology

179

meta-model of this work, for example, the use of

MoSCoW or working with a Product Backlog mod-

elled by means of a spreadsheet. Other teams will

have other experience and other techniques and prac-

tices and will be able to benefit from them when work-

ing with this meta-model.

A future line of work will be to apply these ele-

ments to practical cases outside the Scrum framework

to determine whether the SofIA elements are adequate

or if any additional elements need to be incorporated

into the meta-model.

We also expected to have more students and more

surveys that will allow a statistical analysis to know

in more detail the acceptance of SofIA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the EQUAVEL

project PID2022-137646OB-C31, funded by MI-

CIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF,

EU.

REFERENCES

Ahern, T., Leavy, B., and Byrne, P. (2014). Complex project

management as complex problem solving: A dis-

tributed knowledge management perspective. Inter-

national Journal of Project Management, 32(8):1371–

1381.

Czarnecki, K. and Helsen, S. (2003). Classification of

Model Transformation Approaches. Proceedings of

the 2nd OOPSLA Workshop on Generative Techniques

in the Context of the Model Driven Architecture,

45(3):1–17.

Eisenbart, B., Mandel, C., Gericke, K., and Blessing, L.

(2015). Integrated function modelling: Comparing the

ifm framework with sysml. Proceedings of the Inter-

national Conference on Engineering Design, ICED,

5:1–12.

Escalona, M. and Arag

´

on, G. (2008). Ndt. a model-driven

approach for web requirements. IEEE Transactions

on Software Engineering, 34.

Escalona, M., Torres, J., Mej

´

ıas, M., Guti

´

errez, J., and Vil-

ladiego, D. (2007). The treatment of navigation in

web engineering. Advances in Engineering Software,

38:267–282.

Escalona, M. J., Koch, N., and Garcia-Borgo

˜

non, L. (2022).

Lean requirements traceability automation enabled by

model-driven engineering. PeerJ Computer Science,

8(1990):1–31.

French, S. (2015). Cynefin: Uncertainty, small worlds and

scenarios. Journal of the Operational Research Soci-

ety, 66:1635–1645.

Gonzalez-Perez, C. and Henderson-Sellers, B. (2008).

Metamodelling for Software Engineering. Wiley Pub-

lishing.

Hasan, H. and Kazlauskas, A. (2009). Making sense of is

with the cynefin framework. PACIS 2009 - 13th Pa-

cific Asia Conference on Information Systems: IT Ser-

vices in a Global Environment.

Hidayah, N. W., Sasmita, R. R., Mayangsari, M. K.,

Kusuma, O. G. W., Rante, H., and Fariza, A. (2022).

Invitin project: Scrum framework implementation in

a software development project management. INTEK:

Jurnal Penelitian, 9:58.

Kadenic, M. D., Koumaditis, K., and Junker-Jensen, L.

(2023). Mastering scrum with a focus on team ma-

turity and key components of scrum. Information and

Software Technology, 153:107079.

Kurtz, C. F. and Snowden, D. J. (2003). The new dynamics

of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and compli-

cated world. IBM Systems Journal, 42:462–483.

Liddle, S. (2010). Model-driven software development.

Handbook of Conceptual Modeling, pages 17–54.

Lteif, G. (2024). The 7 timeless steps to guide you through

complex problem solving.

Mar

´

ıa-Jos

´

e Escalona, Laura Garc

´

ıa-Borgo

˜

non, J. G.-G.,

L

´

opez-Nicol

´

as, G., and de Koch, N. P. (2023). Choose

your preferred life cycle and sofia will do the rest. In-

ternational Conference on Web Engineering (ICWE),

pages 359–362.

Mens, T., Van Gorp, P., Varr

´

o, D., and Karsai, G. (2006).

Applying a model transformation taxonomy to graph

transformation technology. Electronic Notes in Theo-

retical Computer Science, 152(1-2):143–159.

O’Connor, R. V. and Lepmets, M. (2015). Exploring the use

of the cynefin framework to inform software develop-

ment approach decisions. ACM International Confer-

ence Proceeding Series, pages 97–101.

Rachmawati, O. C. R., Wardani, D. K., Fatihia, W. M.,

Fariza, A., and Rante, H. (2023). Implementing ag-

ile scrum methodology in the development of sicitra

mobile application. Jurnal RESTI (Rekayasa Sistem

dan Teknologi Informasi), 7:41–50.

Ross, D. and Schoman, K. (1977). Structured analysis for

requirements definition. IEEE Transactions on Soft-

ware Engineering, SE-3(1):6–15.

Saltz, J. and Heckman, R. (2020). Exploring which agile

principles students internalize when using a kanban

process methodology. Journal of Information Systems

Education, 31:51–60.

Schwaber, K. and Sutherland, J. (2020). Scrum guide.

Snowden, D. (2002). Complex acts of knowing: Paradox

and descriptive self-awareness. Journal of Knowledge

Management, 6:100–111.

Snowden, D. (2010). The cynefin framework. YouTube

video, 8:38.

Snowden, D. J. and Boone, M. E. (2007). A leaders guide

to decision making. Harvard Business Review, 11:68–

76.

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

180