The Role of Context to Detect Conflict Expression in Text

Philippe Herr and Nada Matta

LIST3N, University of Technology of Troyes, 12 Rue Marie Curie, 42060 10004 Troyes Cedex, France

Keywords: Textual Semantics, Text, Context, Ambiguity, Conflict, Hermeneutics, Knowledge, NLP.

Abstract: The notion of context, present since Antiquity, has gained increasing importance across various fields such

as linguistic semantics, cognitive psychology, artificial intelligence (AI), and natural language processing

(NLP) since the 1980s. In text analysis, a distinction is made between “internal context” (textual elements

surrounding a linguistic item) and “external context” (circumstances surrounding the production of a fact or

process). Context is thus crucial both for determining the meaning of linguistic signs and for interpreting texts

Although NLP and generative AI systems simulate linguistic exchanges, they often lack explicit internal

representations of contextualization processes This paper aims to shed light on what is meant by “context,”

with a particular focus on “cultural context.” It specifically investigates the expression of conflictual elements

that can be identified in texts through the activation of context.

1 INTRODUCTION

The concept or idea of context, which emerged

implicitly as early as Antiquity, has attracted growing

interest in various fields of knowledge since the

1980s, notably in linguistic semantics, cognitive

psychology, artificial intelligence (AI), and natural

language processing (NLP) (Rastier, 2001). In the

field of text analysis, it is necessary to distinguish

between “internal context,” meaning the textual

elements surrounding the linguistic item under

consideration, and “external context,” referring to the

set of circumstances in which a fact or process is

produced (Hassler et al., 2024).

While NLP and generative AI systems today

make it possible to simulate linguistic exchanges in

human–machine interactions in a convincingly

realistic way, they do not provide an explicit

representation of how linguistic elements are

combined across the different levels of text analysis

(Gastaldi et al., 2024). It is therefore of interest to ask

how potentially active contexts can be identified and

how they operate to generate meaning for a textual

element. First and foremost, we must better define

what is meant by “context,” with particular emphasis

on the notion of “cultural context.”

Our research focuses on written texts. We

approach written texts as structured objects organized

into various levels, whose complex interactions

generate semantic perceptions in the reader–

interpreter (Rastier, 2010). More specifically, we

examine how context enables the identification and

characterization of textual elements that express

conflict. The texts considered span all types of

discourse: legal, religious, scientific popularization,

etc.; private, public; normative, playful; explanatory,

argumentative, etc. (Bronckart, 2008), and all genres:

narrative (fictional or real stories, e.g., novels),

theatrical, poetic, or "literature of ideas" (defined

primarily by its defense or refutation of a thesis). Our

hypothesis is that any type and genre of text may

contain points of conflict, whether in specific parts or

as a whole.

Our specific interest in the expression of conflict

stems from a preliminary study (Matta No.et al.,

2024). The connection between context and elements

of conflict. To identify linguistic segments expressing

conflict and uncover conflictual dimensions, the

reader–interpreter had to engage the identification of

contextual explication, relying not only on their

linguistic knowledge (linguistic competence) but also

on their knowledge of the natural and cultural world.

In the first part of this article, we provide a

conceptual framework for understanding “context”

and “cultural context.” The second part focuses on the

notion or concept of conflict, ultimately preferred

over confrontation. The third part analyzes a text

example by activating only the linguistic context and

considers the limitations of such approach in

identifying conflictual tensions.

Herr, P. and Matta, N.

The Role of Context to Detect Conflict Expression in Text.

DOI: 10.5220/0013712000004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

401-408

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

401

2 CONTEXT vs. CULTURAL

CONTEXT

The notion of context is relevant to numerous

disciplines, including linguistics, semantics,

pragmatics Austin J. (1970). Bazire and Brézillon

(2005) highlight the challenges associated with

understanding context by identifying its main

components through an analysis of definitions across

cognitive science domains. They trace the evolution

of explicit uses of context in industrial applications.

In knowledge engineering, Bachimont (2005)

emphasizes that the definition of an ontology is linked

to “the meaning given in context” (2005, p. 343).

Chuntao and Caiying (2019) underline the

importance of contextual relevance for textual

coherence and assert that language production and

comprehension cannot be separated from context.

Condamines (2005) questions whether it is possible

to decontextualize linguistic phenomena,

emphasizing the interdependence between linguistic

features and the situation in which they are produced.

This theoretical overview highlights the variety,

complexity of the concept of context. Is it even

possible to identify the relevant contexts in a text, to

measure their degree of relevance and their

interactions in order to construct coherent and

explainable interpretive paths? For Adam (2012) the

text possesses a structural cohesion that must be

accounted for as completely as possible, based on the

linguistic elements functioning in each of its

segments (word, phrase, sentence…) and levels (e.g.,

the clause – considered the first hermeneutic level by

Rastier – the paragraph, the whole text). In response

to Schmoll’s (1996) straightforward question: “Is the

notion of context operative?” – which interrogates its

theoretical validity – we can at least say that textual

cohesion is matched by textual coherence, an

interpretive phenomenon that goes beyond the text’s

internal structure and thus justifies maintaining the

hypothesis of an operative external context, at least

heuristically.

Relying on Lichao (2010), Matta et al, (2023), and

Beyssade (2024), we propose a minimal and abstract

initial definition of context as: the set of information

that enables the identification and characterization of

an element. Every act of discourse is a text made

concrete, that is, anchored in a situation. In the same

way, since reading is a situated act, a text read by a

reader–interpreter becomes actualized as discourse

(an internal discourse). Our minimal and abstract

definition of context is not sufficient here. In

discourse, both spoken and written, we distinguish

between the strictly linguistic context (words deriving

meaning from one another based on the language

system) and the extralinguistic situational context

(who is speaking, to whom, under what

circumstances, where, when, how, with what

intentions, etc.), which conditions the interpretation

of utterances – this is the domain of pragmatics

Austin J, (1970). In the individual reading of a written

text, the immediate situational extralinguistic context

appears less decisive: the reader is in solitary

interaction with the text – at least, this is our current

assumption. So, what constitutes the extralinguistic,

or more precisely, extratextual context? It consists of

the representations activated or activatable in the

reader’s memory (or mind?), enabling them to

actualize the text into a coherent discourse – coherent,

that is, for them. This actualization of the text into

discourse depends on cognitive processes of

semantic, pragmatic, encyclopedic, and cultural

orders, some of which are conscious, others not.

These include encyclopedic knowledge, social

representations, cultural frames of reference, and

genre – and discourse-type-related expectations. A

minimal interpretive context is activated as a global

“horizon of expectation” upon approaching the text,

then progressively enriched and refined throughout

the reading process, as the reader builds mental

configurations and hypotheses of meaning according

to their interpretive competence (Rastier, 2010). The

context encoded linguistically and textually (the left–

right linear context of a linguistic element, as well as

the top–bottom typographic context, including

paratext and headlines) activates an interpretive

cognitive context aimed at overall coherence. A

global discursive configuration progressively unfolds

in this “dialogue” with the text. In addition to

linguistic competence (the language code), reading

mobilizes textual competence (a “grammar of text,”

an acquired understanding of textual structures),

pragmatic competence (relevant here to interpret

interlocution situations represented in the text),

shared presupposition knowledge (what Stalnaker,

1998, calls the Common Ground), encyclopedic

knowledge about the real world and fictional worlds

(Beyssade, 2024; Adam, 2012).

Our goal is to better understand what is

encompassed by the notion of “cultural context,”

which at this stage remains a working hypothesis.

Related to these studies, a definition may be

formulated as follows: Cultural context encompasses

the structured set of knowledge, beliefs, norms,

conventions, values, representations, practices, and

symbolic references shared by a community at a

given time, which shape the production, circulation,

and reception of discourse. Cultural context thus

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

402

constitutes a collective memory that guides – and may

even condition – the interpretation of texts by

activating implicit frames of understanding. Cultural

context influences both the production and the

interpretation of texts, helping to actualize them into

coherent discourses (Hoskovec, 2010; Lichao, 2010;

Beyssade, 2024). As we stated before, we aim to

detect conflict in text using context. So, let-us define

the notion of conflict.

3 THE CONCEPT OF CONFLICT

The choice of term – “conflict” or “confrontation” –

to designate the central concept was not made without

debate. Gauducheau & Marcoccia (Gauducheau &

Marcoccia, 2023) point out that conflict can be

expressed indirectly, implicitly, or managed through

discursive avoidance strategies, and thus without

confrontation. Conversely, pure confrontation can

occur without conflict – as in the case of comparing

testimonies in a legal inquiry, which doesn’t

necessarily involve emotional escalation or hostility,

hence no conflict. Similarly, a conflict may exist –

such as over water resource allocation – without

direct confrontation between farmers and local

authorities.

In the literature, “conflict” is the preferred

hypernym used to encompass all forms of

disagreement or opposition, whether these manifest in

confrontation (for clarification on conflict ontology:

Greco Morasso, 2008; Dehais, 2000). Our aim is to

define the conceptual domain of conflict so that it

may be operational in identifying conflict expressions

through explainable contextualization processes.

We aim to determine how different types of

contexts contribute to identifying and interpreting

expressions of conflict in texts, with special attention

to the role of cultural context. This requires a clear

definition of conflict, distinctions between its types,

and the development of analytical methods to assess

the interpretive role of context. Several challenges

arise: enabling NLP to more accurately detect textual

expressions of conflict, enriching linguistic and

semantic theories on context, and potentially

proposing a tool for text analysis.

While an ontology of conflict could be defined

based on prior work (Dehais, 2000; Müller, 2000;

Talmy, 2000; Greco Morasso, 2008), the main

challenge lies in accounting for the complexity and

diversity of contextual factors that define conflict –

especially cultural context.

The expression and representation of conflict are

of interest to linguistics, semantics, and knowledge

engineering. Dehais and Pasquier (2000) propose an

ontology and typology of conflict in cognitive science

that clarifies terminology and conceptual structure.

Müller and Dieng (2000) offer a broad overview of

conflict definitions, emphasizing the diverse contexts

in which conflicts arise. Castelfranchi (2000)

distinguishes psychological from internal conflicts,

revisits Lewin’s (1948) typology, and proposes

formal models for conflict detection and

management. Fayol (1985) adopts an approach rooted

in linguistics and cognitive psychology to analyze the

construction and interpretation of conflict-driven

narratives. Sauquet and Vielajus (2014) explore

conflict in intercultural mediation related to social

and cultural dimensions of conflict. Greco Morasso

(2008) clarifies the ontology of conflict,

distinguishing interpersonal hostility (emotional

level) from propositional incompatibility (intellectual

level), and shows that the meaning of conflict varies

across cultural and social contexts.

A synthesis of these approaches allows us to

propose the following definition of conflict: a

discursive or interactional situation in which two or

more positions, interests, values, representations, or

intentions come into opposition – explicitly or

implicitly – with the potential outcome being

resolution, domination, or coexistence of these

divergences. In texts, conflict is expressed through

linguistic forms (in the language code), discursive

forms (how language is used in context – pragmatics

and rhetoric), or symbolic forms (codified cultural or

ideological representations) that signal tension,

incompatibility, or confrontation. Conflict may be

explicitly expressed (e.g., through markers of direct

opposition, confrontation verbs, syntactic structures,

etc.) or implicitly conveyed – its interpretation then

relying on the activation of encyclopedic knowledge

(general world knowledge), cultural knowledge

(collective socio-historical knowledge), or situational

knowledge (shared assumptions presumed known or

accessible to the interlocutors in a given context).

Our object of study is the written text: we do not

treat conflicts as social or historical facts but as

discursive representations.

In many domains, conflict primarily appeared

through language. This is the case with legal conflicts

(resulting in exchanges or transcripts), discursive

conflicts (expressed in debates or arguments), and

semantic conflicts (where lexical interpretation

disagreements lead to misunderstandings). Pragmatic

conflicts concern the contextual use of language,

particularly through conflicting speech acts

(accusations, reproaches, denials). Intertextual

conflicts are constructed in the relationship between

The Role of Context to Detect Conflict Expression in Text

403

texts that contradict, respond to, or refute each other

through citations or allusions. Finally, ideological

conflicts involve opposing value systems that

underpin discourse.

The Relevance of Cultural Context in Identifying

Conflicts

The specific importance of cultural context –

compared to linguistic context (the left-to-right

sequence of language units) and situational context

(the immediate conditions of enunciation) – lies in its

interpretive depth: it determines the axiological

frameworks through which speakers perceive and

categorize utterances. It thus guides the recognition of

conflict markers, forms of disagreement, and implicit

normative systems embedded in discourse. Conflict

itself is a cultural construct. What constitutes a

manifestation of conflict in one cultural setting may

be interpreted elsewhere as a simple disagreement or

a normative interactional ritual. The use of rhetorical

devices such as irony or indirect criticism varies

across cultural groups and micro-cultures. Likewise,

some cultures value explicit verbal confrontation,

while others regard it as a violation of interactional

norms. Ignoring these frameworks risks

misinterpretation, whether in real-life analyses or in

texts. Cultural context is often implicit in texts.

Unlike linguistic context, which is observable in the

text itself, it is usually inferential: it relies on shared

knowledge, historical references, and implicit norms.

It operates regardless of the type of discourse –

legal, religious, scientific, or literary. It enables the

identification of conflicting value systems, culturally

anchored discursive strategies, and the interpretive

frameworks needed to detect expressions of conflict.

4 DETECTING CONFLICT

THROUGH ACTIVATION OF

INTERNAL CUES

Ultimately, our objective is to demonstrate that taking

cultural context into account is necessary to identify

and characterize certain conflictual tensions within a

text. However, as a first step, let us examine how the

expression of conflict can be detected through cues

that do not require reference to cultural context.

Our previous analysis of the notion of conflict

leads us to identify several types of cues. Some

explicitly indicate conflict; others are implicit but

may suggest the presence of conflict. More often than

not, only the combination of cues enables the

detection of a conflictual dimension.

The table of types of indices for identifying

conflict tensions is based on knowledge of French

grammar (Rigel M. et al., 2014), semantics (Lyons J.,

1980) and more broadly language sciences (Ducrot O.

& Schaefffer J.-M., 1999)." This list is incomplete

and will be gradually expanded and refined.

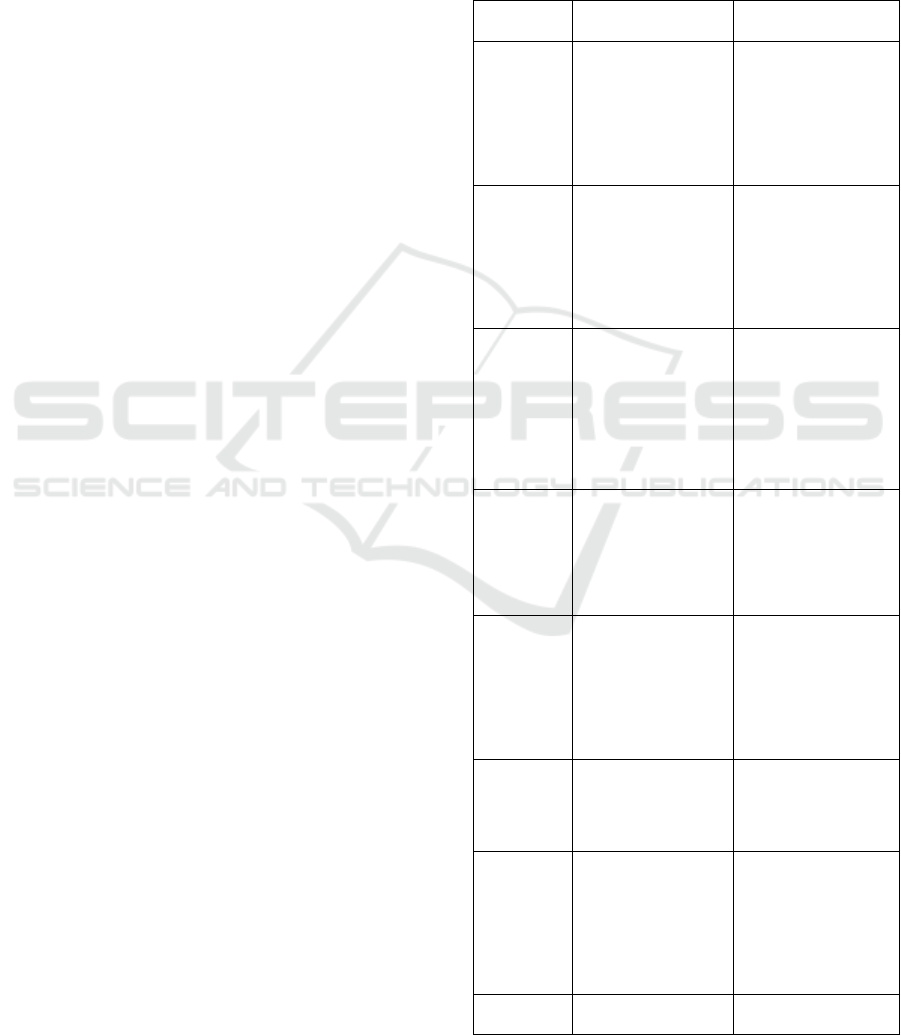

Table 1: Table of Indices Types for Detecting Conflictual

Tension.

Type of

Indices

Definition Examples

Lexical

Lexemes or

nominal/verbal phrases

whose meaning includes

antagonism, refusal, or

confrontation—directly

or indirectly signaling a

conflictual or

intersubjective tension.

“contest,” “refuse,” “to

oppose,” “internal

tensions,” “to come into

conflict with,” “to reject

outright”

Grammatical

Pertains to grammatical

morphology: agreement,

tense, mood, negation,

determiners, pronouns,

conjugations… e.g.,

morphemes or structures

that mark negation or

distancing.

“He does not want to

yield” (negation); “He

might have lied”

(enunciative distancing)

Syntactic

Related to sentence

structure, syntactic roles

(subject, object...),

constituent order,

coordination,

subordination, or

p

ropositional structure

(e.g., conditional

clauses).

“He wanted to come, but

s

he refused”; “Although

he’s right, we must go”;

“If you keep this up…”

Pragmatic

Speech acts (actions

p

erformed by speaking,

with clearly identifiable

intent) or implicatures

(suggested meaning)

expressing

communicative tension.

“Shut up now” (explicit

threat); “I suggest you be

careful…” (implicit

threat); “You always do

that, don’t you?” (implicit

reproach)

Enunciative

Marks of the speaker's

subjective positioning

toward their own

statement, showing

involvement, distance,

judgment, or attitude—

modulating the intensity

of conflict expression.

“It seems he cheated”; “In

my opinion, this is

unacceptable”; “I fear he

sabotaged the project”

(emotional modalization +

implicit accusation); “He

allegedly ignored the

instructions”

Referential

References to entities,

groups, or events

p

resented as opposed or

in tension; may imply

latent or explicit conflict.

“The protesters and the

police…”; “ Two

worldviews are clashing

on the TV set ”

Discursive

Indicators tied to

discourse structure

(dialogue or monologue)

that express opposition,

disagreement, or

argumentative tension via

adversative links,

rebuttals, or refutations.

“Granted… but…”

(concession); “- You

wanted this. -

N

o, you

did.” (conflictual reply /

direct refutation); “While

s

ome applauded, others

walked out.”

Symbolic

Linguistic elements

(metaphors, imagery,

“Fire and ice stood face to

f

ace”; “Between them, it

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

404

Type of

Indices

Definition Examples

mentioned objects) that

figuratively or

allegorically evoke

separation, confrontation,

or incompatibility,

implying implicit

conflict.

was a minefield” (The

conflict presupposes a

relationship, shown here

by “stood face to face”

and “between them”)

Stylistic /

Rhetorical

Formal devices (figures

of speech) that produce

contrast, contradiction, or

reversal, suggesting or

reflecting a conflictual

tension.

“Deafening silence”

(oxymoron); “I live, I die”

(antithesis)

Prosodic /

Typographic

punctuation

Graphic or rhythmic

markers in writing that

mimic or transpose

effects of intonation,

rhythm, volume, or

emphasis—signaling

enunciative tension or

affective intensity.

Expressive punctuation:

“You lied to me again…

Again!” (ellipsis +

exclamation = emotional

intensity + accusatory

insistence); Repetition:

“No, no, no, I don’t

believe you.” (effect of

stubborn refusal, growing

tension)

It is worth noting that so-called “symbolic”

indicators raise questions. For example, fire vs. ice,

or minefield, are allegorical and metaphorical images

that are only activated as such within a given cultural

context - not necessarily in another. At the very least,

it is a matter of identifying some indicators as being

potentially interpretable as symbols of something,

without necessarily specifying what they symbolize.

5 CASE STUDY

The example of text analyzed comes from Chapter 19

of Candide, a philosophical tale by Voltaire published

in 1759 in France: The original text, in French:

“Quand nous travaillons aux sucreries, et que la

meule nous attrape le doigt, on nous coupe la main ;

quand nous voulons nous enfuir, on nous coupe la

jambe : je me suis trouvé dans les deux cas. C’est à ce

prix que vous mangez du sucre en Europe.”The

Literary translation can be

1:

“When we labor in the

sugar works, and the mill happens to snatch hold of a

finger, they instantly chop off our hand; and when we

attempt to run away, they cut off a leg. Both these

cases have happened to me, and it is at this expense

that you eat sugar in Europe.”

This block of this text displays features of

cohesion (grammatical) and coherence (semantic,

logical, enunciative, argumentative, narrative) that

allows for a preliminary interpretation. The objective

is to interpret the part based only on the clues it

contains – that is, internally – seeking to identify

1

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Candide/Chapter_19

conflictual tensions (regardless of their type or level),

without relying on surrounding textual context or

extra-textual knowledge. On this basis, our

interpretive process, guided only by the types of

indices listed in 0 and linguistics analysis principles

(ADAM, 2012), followed the steps below:

5.1 Interpretive Steps

1. Identify WHAT is being discussed:

Establish the “world” in question—

considered a preliminary “domain of

definition” with heuristic value. This can be

linked to referential Category.

2. Identify WHO is involved: Determine which

entities are present (real persons, narrators,

characters), and what kind of physical or

discursive relationships they have. What

linguistic elements refer to them?

3. Identify the verbs: What semantic

relationships exist among them (synonymy,

antonymy, hypernymy, etc.)? What lexical

or semantic fields do they belong to?

4. Analyze the syntactic structures: Look for

recurring structures (e.g., parataxis,

coordination, subordination), structural

parallelisms, or contrasts.

5. Identify temporal elements: Are there

expressions of anteriority, posteriority,

simultaneity, etc.? It can be expressed

through grammatical and syntaxical indices.

6. Identify logical relationships: Detect explicit

or implicit cause-effect relations, conditions,

or hypothetical constructs.

7. Map relationships between entities: Identify

named entities and pronouns. If any entity is

implicit, try to infer its identity. Clarify who

does what to whom and how.

8. Pragmatic approach: Identify and interpret

speech acts Austin J., (1962) and their

discursive roles (e.g., indirect accusations).

ChatGPT 4 has been used to check if this type of

generative AI algorithm can be used to detect conflict

in text. Firstly the description of Cultural context and

conflicts noted in sections (2, 3) has been given to the

algorithm as same as the table of indices (0) and the

interpretative steps we defined (5.1.) Then the

following prompt has been submitted:

“Here is the example to be analyzed:

[EXAMPLE]. The goal is to identify and detect

conflictual tensions or conflicts (of any type or level)

within the text. Analyze the example without using

The Role of Context to Detect Conflict Expression in Text

405

textual context (i.e., the rest of the text) or any

encyclopedic or cultural knowledge. Rely on the

types of indicators listed in the table (0) . Follow

interpretative steps (5.1). The first column presents

each interpretive step. The second column provides

an analysis based only on internal elements of the

text. The third column identifies oppositions or

conflicts revealed through the analysis. At the end of

the table, suggest additional internal indicators

relevant to conflict detection, and their interpretation.

Then produce a written synthesis of your table”.

5.2 Result Generated by the ChatGPT4

0 presents an analysis strictly based on the text itself,

without drawing on any external encyclopedism or

cultural knowledge. It relies only on linguistic,

syntactic, and semantic cues internal to the text.

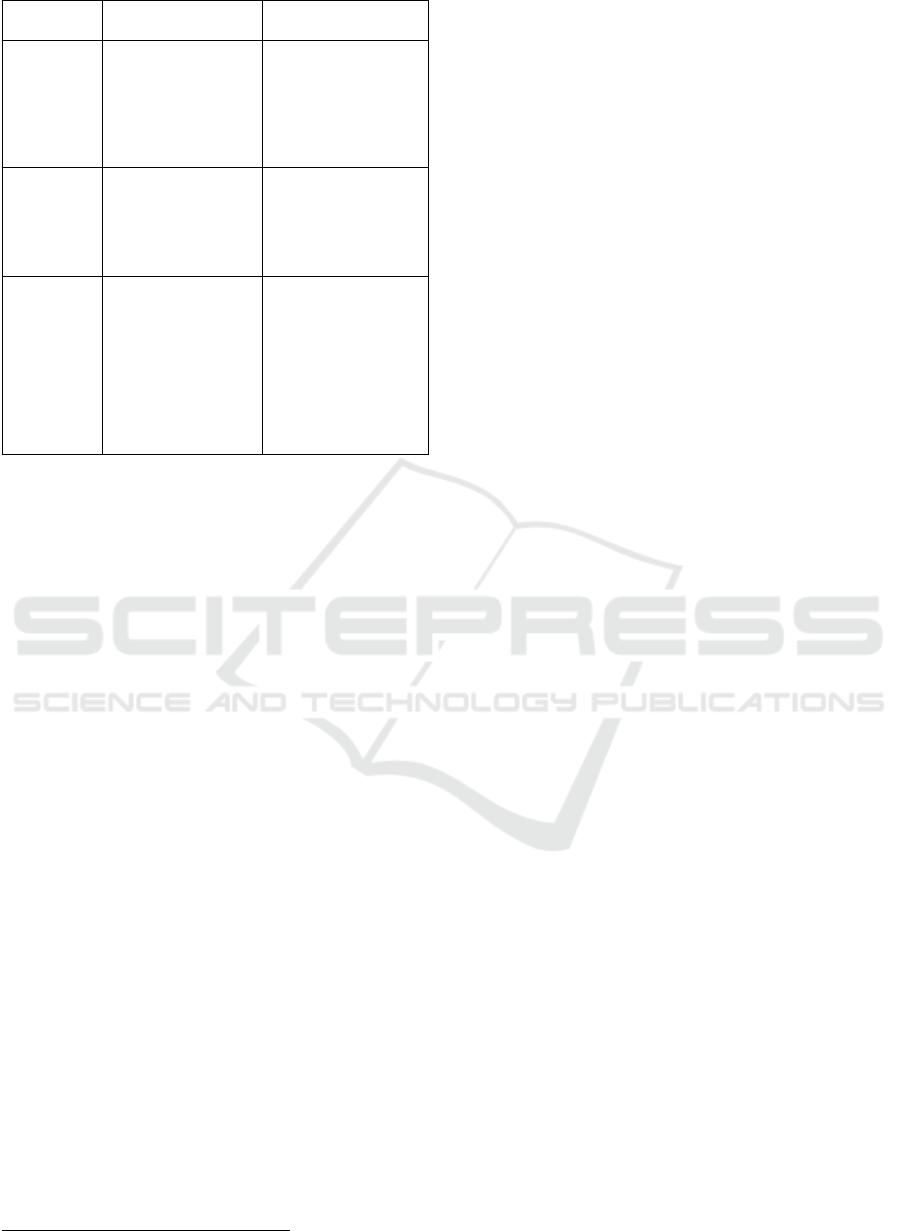

Table 2: Internal textual analysis table with detection of

oppositions and conflicts (without contextual data).

Step

Analysis (based on internal

textual elements)

Oppositions / Conflicts

Revealed

0.

The text forms a structured

whole. It presents two similar

situations (introduced by

"when") leading to a punitive

consequence. A conclusion

results in the form of a

generalization addressed to a

recipient ("you").

Structural: repetition + final

rupture → tension between

a cyclic logic (recurrent

violence) and a final

revelation or denunciation.

1.

It concerns an activity (let’s

work), an incident (the mill

catches our finger), an attempt

to flee (we want to escape),

corporal punishments (our

hand/leg is cut off), and

consumption (you eat sugar).

Semantic: opposition

b

etween local physical

action and distant

consumption; tension

b

etween production and

consumption.

2.

- we: group including the

speaker. - I: the speaker

himself, included in we. - they

(« on » in French): indefinite

agent acting upon us. - you:

designated recipient at the end.

Relations: they (« on » in

French) acts on us, I confirm

the experience, you receive an

indirect effect.

Enunciative and relational:

conflict between we/I

(suffering) and they (« on »

in Fr.) (inflicting), and

b

etween I/we and you

(beneficiaries not involved

in the suffering).

3.

Main verbs: work, catch, cut,

want, flee, found myself, eat. -

Oppositions: work (productive

action) ↔ cut (punitive action).

- Semantic fields: action, will,

pain, consumption. - Logical

grouping: activity verbs →

sanction verbs → consequence

verbs.

Lexical / semantic: tension

b

etween positive active

verbs (work, want) and

violent passive verbs (cut);

opposition between

individual will and brutal

sanction.

4.

- Structural repetition: two

sentences beginning with

"when we..." followed by "they

Syntactic: contrast between

the mechanical regularity of

the first structures and the

Step

Analysis (based on internal

textual elements)

Oppositions / Conflicts

Revealed

cut off our...". - Binary

structure: initial condition →

violent result. - Rupture: the

last sentence breaks the

previous pattern and directly

addresses a "you".

uniqueness of the last →

conflict between violent

routine and awareness.

5.

When: simultaneity or

recurrent condition. - I found

myself: past perfect, personal

moment. - You eat: present,

generalizing and current.

Temporal: opposition

b

etween lived past (I found

myself) vs present ("you

eat") → tension between

memory of experience and

ignorance of the present.

6.

- Implicit causal relations:

when A, then B. - Last sentence

makes explicit a logical

relation: "It is at this price

that..." → consequence of the

previous narrative.

Logical and moral: cause-

effect relation between pain

and consumption; implicit

moral conflict between

b

anal act (eating) and its

hidden consequence.

7.

- we perform two actions

(work, want to flee) and suffer

two actions (they cut off

our...). - I am affected by both

events. - you eat, linked to the

price of the recounted events.

Pragmatic / interactional:

conflict of positions and

effects: we suffer what you

indirectly cause; implicit

hierarchy among actors.

8.

- we: homogeneous group in

discourse. - I: emphasis on

personal experience within the

group. - you: external position,

indirectly but explicitly

concerned. This creates a

confrontation effect between

I/we and you.

Enunciative and

axiological: opposition

b

etween inclusion (we) and

distancing (you); conflict of

perspectives between lived

suffering and implicit

comfort.

9.

- Repetition of constructions

"when... they cut off our..." →

confinement, lack of choice. -

Use of the pronoun "they"

("on" in Fr.) without

specification → impersonal

threat. - Implicit opposition

I/we ↔ you. - Last sentence

b

egins with "It is at this price":

expression of a paradoxical

equivalence between pain and

consumption.

Structural / symbolic:

repetition = confinement;

they (« on » in Fr.) =

impersonal threat; you =

unnamed complicit

addressee; "at this price" =

conflict of values.

5.3 Discussions of the ChatGPT4

Results

In this example, conflicts emerge through clearly

structured formal oppositions. Personal pronouns

establish a power dynamic: we (workers, the speaker

group) and I (individual experience) are opposed to

they (an anonymous punitive force) and you (the

consumer audience). This enunciative opposition

reveals a relational and moral conflict between those

who suffer physical violence and those who benefit

from it, whether knowingly or unknowingly. The

repetitive syntactic structure in the first two sentences

(“when... they cut...”) creates a mechanical,

inescapable pattern that reinforces the idea of

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

406

systemic conflict based on domination. The contrast

between verb tenses (narrative present and past

perfect) and the generalized present in “you eat”

reflects a temporal tension between lived experience

and ongoing consumption. Finally, logical structures

such as the conditional clause “It is at this price

that...” point to a cause–effect relationship between

suffering and comfort, revealing an implicit moral

conflict regarding the conditions of commodity

production. These various indicators suggest a

conflict of axiological, social, and political nature,

rooted in the invisibilities of real violence within

consumption systems.

5.4 Limitations of an Analysis Without

Encyclopedic or Cultural Context

Without cultural context, and using only intra-textual

linguistic clues, one can detect the violence of the

situation – and even infer a possible “relational and

moral conflict between those subjected to physical

harm and another group that benefits from it without

suffering the consequences.” However, it is not

possible to infer the deeper critical scope of the

conflict – namely, the contrast between

Enlightenment values and the colonial reality of 18th-

century Europe.

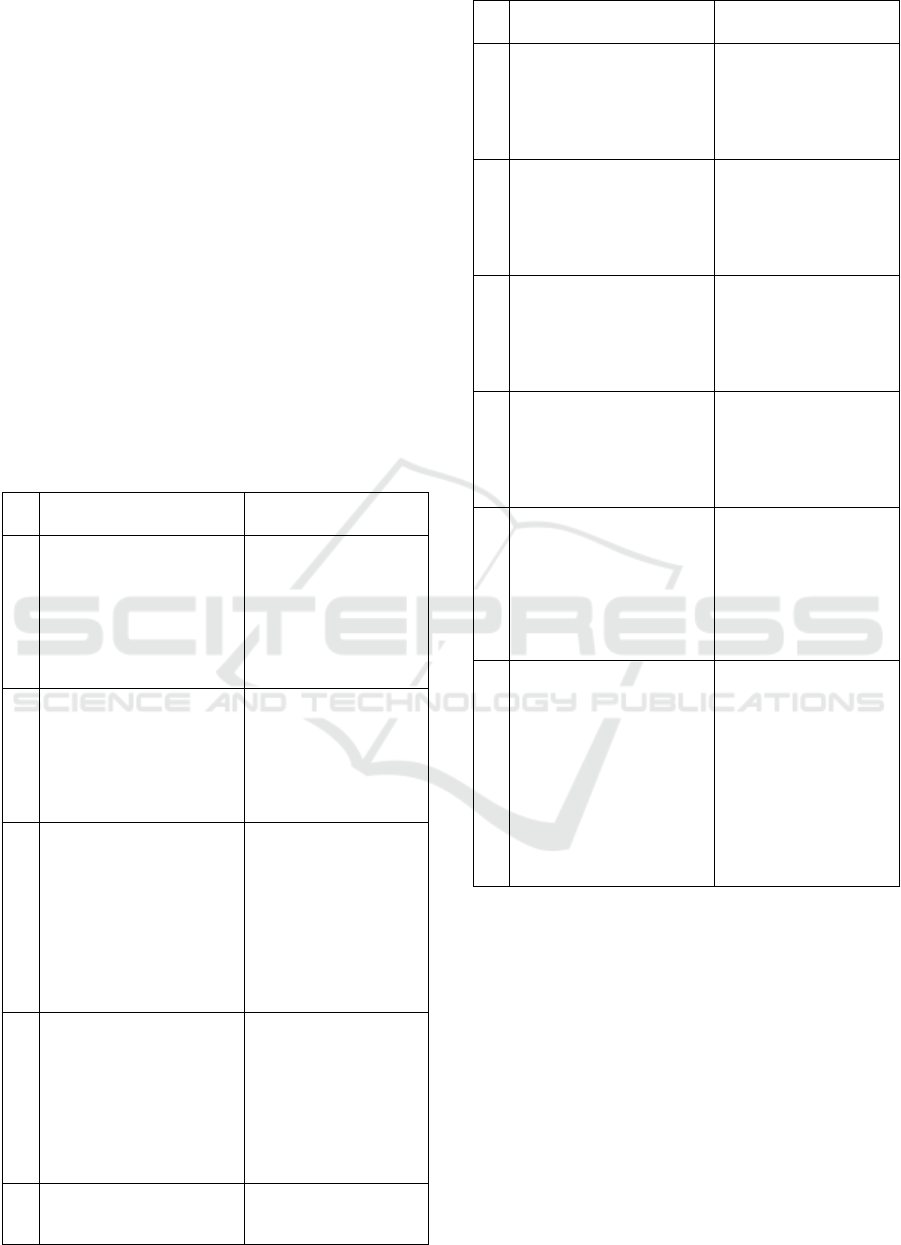

Table 3 illustrates a few specific points where

cultural context would be essential for interpreting the

example:

Table 3: Few specific points where cultural context would

be essential for interpreting the example.

Aspect

analyzed

Interpretation

without cultural

context

Interpretation with

cultural context

Interpretation

of “you”

Unidentified

addressee; may be an

individual or collective

interlocuto

r

Direct address to

Europeans, readers

complicit in the slavery

system

Meaning of “at

this price”

Personal cost,

individual suffering

Moral and political cost

of European

consumption (sugar =

product of slavery)

Status of the

speaker

Suffering subject,

witness of a brutal

system

Spokesperson for the

oppressed, allegorical

figure of social critique

Effect

produced on

the reader

(hypothesis)

Compassion,

indignation towards

violence

Moral discomfort,

questioning of collective

responsibility

6 CONCLUSION

The analysis in this paper has demonstrated that

identifying and detecting the expression of conflict in

a text cannot be accomplished without careful

consideration of the textual elements forming the

internal context. By integrating insights from

traditional grammar, semantics, and pragmatics, we

have shown that conflict can, to a certain extent, be

delineated on the basis of linguistic indicators alone -

that is, through an interpretation internal to the

language system, without needing to appeal to extra-

textual context.

Cultural context, understood as a shared memory

of representations, values, and norms, plays a crucial

role in activating the interpretive frameworks

necessary for detecting conflictual tensions. Without

activating an extra-linguistic context, some conflicts

remain invisible or are poorly interpreted. Thus,

cultural context is not a mere backdrop; it functions

as a hermeneutic operator essential to textual

interpretation.

This approach highlights the need to integrate

more refined and culturally informed

contextualization models. Conflict analysis cannot

remain confined to the linguistic analysis of the text;

it must also mobilize cultural knowledge to clarify

what is implied or latent. We aim at analyzing other

types of text to enrich to define a methodology that

guides to integrate some elements of cultural context

in text analysis and conflict detection.

This study is as first steps to identify guidelines

and Patterns that help the identification of conflicts

and cultural context when analyzing text using

Generative AI algorithms. We aim at studying

linguistics and semantic relations from one side and

testing more LLMs algorithms.

REFERENCES

Adam J-M., « Le modèle émergentiste en linguistique

textuelle ». In: L'Information Grammaticale, N. 134,

2012. L'émergence : un concept opératoire pour les

sciences du langage ? pp. 30-37. doi:

https://doi.org/10.3406/igram.2012.4211

Austin J., Quand dire, c'est faire (trad. Gilles Lane), Paris,

Editions du Seuil, 1970 – traduction de (en) How to do

things with Words : The William James Lectures

delivered at Harvard University in 1955, Oxford, J.O.

Urmson, 1962.

Bachimont B., « Corpus et connaissances : de l’extraction

linguistique à la modélisation conceptuelle » ,

Sémantique et corpus, (dir. A. CONDAMINES),

The Role of Context to Detect Conflict Expression in Text

407

ouvrage de la série Cognition et traitement de

l’information. Lavoisier-Hermès, 2005, pp. 319-346.

Bazire M., et Brezillon P. (2005) « Understanding Context

Before Using It ». In : Dey A., Kokinov B., Leake D.,

Turner R. (eds) Modeling and Using Context.

CONTEXT 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science,

3554. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Beyssade C., « Signification et mises à jour du contexte »,

Le contexte en question. Série : Les concepts fondateurs

de la philosophie du langage, volume 10 (Chapitre 13).

Sous la direction de Gerda Hassler. ISTE éditions, pp.

269-293, 2024.

Bronckart, J-P., « Genres de textes, types de discours, et «

degrés » de langue ». In: Texto !, 2008, vol. 13, n° 1.

https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:37287

Castelfranchi C., « Conflict ontology ». Computational

conflicts : conflict modelling for distributed intelligent

systems, ed. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2000 .

pp. 21-40.

Chuntao Li, Caiying Han Caiying. « Contextual Relevance:

The Basic Condition for Textual Coherence ».

International Journal of Language and Linguistics. Vol.

7, No. 1, 2019, pp. 42-49. doi:

10.11648/j.ijll.20190701.16

Condamines A. (dir.), Sémantique et corpus, ouvrage de la

série Cognition et traitement de l’information.

Lavoisier-Hermès, 2005.

Dehais F. et Pasquier Ph., « Conflit : vers une définition

générique ». In: Acte de l'Interférence Homme Machine

(Biarritz, France), 2000. pp.1-13. hal-04531115

Ducrot O, Schaeffer J.-M., Nouveau dictionnaire

encyclopédique des sciences du langage, Points Essais.

Paris, 1999

Fayol M., Le récit et sa construction : une approche de

psychologie cognitive, Delachaux & Niestlé, coll.

Actualités pédagogiques et psychologiques, 1985

Gastaldi J. L., Moot R., Retore Ch., « Le contexte en

traitement automatique des langues », Le contexte en

question. Série : Les concepts fondateurs de la

philosophie du langage, volume 10 (Chapitre 14). Sous

la direction de Gerda Hassler. ISTE éditions, pp. 295-

323, 2024. ⟨hal-04008967⟩

Gauducheau N., Marcoccia M., « La violence verbale dans

un forum de discussion pour les 18-25 ans : Comment

les jeunes jugent-ils les messages ? ». La haine en ligne,

Réseaux, 2023/5 N°241, La Découverte.

Greco Morasso S., « The ontology of conflict ». Pragmatics

& Cognition 16 (3), 2008, pp. 540-567.

Hassler G. (Dir.), Le contexte en question. Série : Les

concepts fondateurs de la philosophie du langage,

volume 10 (Chapitre 14). Sous la direction de Gerda

Hassler. ISTE éditions, pp. 295-323, 2024.

Hoskovec T., « La linguistique textuelle et le programme

de philologie englobante », Verbum XXXII, n°2, 2010.

Lichao S., « The Role of Context in Discourse Analysis »,

Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 1, No.

6, pp. 876-879, November 2010, ACADEMY

PUBLISHER, Manufactured in Finland ;

doi:10.4304/jltr.1.6.876-879

Lyons J., Sémantique linguistique, Larousse, 1980

(traduction de : Semantics, vol. 2, London : Cambridge

University Press, 1977)

Matta No., Matta N. and Herr Ph. (2024). « Importance of

Context Awareness in NLP ». In Proceedings of the

16th International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management - Volume 3: KMIS, 2024 ; ISBN 978-989-

758-716-0, SciTePress, pages 280-286. DOI:

10.5220/0012994700003838

Müller H.J. and Dieng R., « On Conflicts in General and

their Use in AI in Particular ». Computational

conflicts : conflict modelling for distributed intelligent

systems, ed. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2000.

pp. 1-20

Rastier F., Arts et sciences du texte, Paris, PUF, 2001

Rastier F., Sémantique et recherches cognitives, Paris, PUF,

coll. Formes sémiotiques, 2010.

Rigel M., Pellat J-Ch., Rioul R., Grammaire méthodique du

français, PUF, Paris, 2014 (5e édition)

Sauquet M., Vielajus M., « Le désaccord et le conflit : entre

affrontement et évitement ». Chapitre 11 de l’ouvrage

collectif : L’intelligence interculturelle : 15 thèmes à

explorer pour travailler au contact d’autres cultures.

Essai n°205. Editions Charles Leopold Mayer, Paris,

2014

Schmoll P.. « Production et interprétation du sens : la notion

de contexte est-elle opératoire ? », Contexte(s), Scolia

[sciences cognitives, linguistique et intelligence

artificielle / revue de linguistique], 1996, 6, pp.235-255.

Halshs-02071397

Talmy L., Toward a Cognitive Semantics. Cambridge,MIT

Press, 2000.

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

408