Explaining the Judges’ Decisions Criteria

Aerty Santos

1 a

, Gabriel Silveira de Queir

´

os Campos

3 b

, Cristine Griffo

5 c

,

Eliana Zandonade

4 d

and Elias de Oliveira

1,2 e

1

Programa de P

´

os-Graduac¸

˜

ao em Inform

´

atica, Universidade Federal do Esp

´

ırito Santo, Vit

´

oria, Brazil

2

Departamento de Arquivologia, Universidade Federal do Esp

´

ırito Santo, Vit

´

oria, Brazil

3

Faculdade de Direito de Vit

´

oria, Vit

´

oria, Brazil

4

Departamento de Estat

´

ıstica, Universidade Federal do Esp

´

ırito Santo, Vit

´

oria, Brazil

5

Eurac Research, Bolzano, Italy

Keywords:

Knowledge Organization, Clustering, Large Language Models, Information Extraction, Judicial Decision.

Abstract:

The identification of named entities in free text is a foundational research area for building intelligent systems

in text and document mining. These textual elements allow us to evaluate the reasoning expressed by document

authors. In a judicial decision, for example, by identifying time-related entities, an intelligent system can as-

sess and verify whether a sentence issued by a justice agent falls within socially agreed-upon statistical param-

eters. In this study, 769 judicial decisions from the S

˜

ao Paulo court were evaluated. Our experiments compared

the extreme time-value sentences against those with the lowest sentence, for instance, to infer the expressions

that justified and have explained their values. The results revealed differences in sentence severity among rob-

bery, drug trafficking, and theft, as well as in how judges cluster based on their sentencing behavior. The study

also highlights anomalies in sentencing and links them to specific textual justifications, demonstrating how

judges’ decisions can reflect both legal criteria and subjective biases. [. . .] In a lawsuit the first to speak seems

right, until someone comes forward and cross-examines. (Proverbs 18:17)

1 INTRODUCTION

Information retrieval tools have significantly im-

proved over the last decade. Companies like Google,

Yahoo, and Bing provide powerful search engines that

enable near-instantaneous access to vast amounts of

documents worldwide. Nevertheless, we need to fur-

ther improve these tools to provide the user with better

search engine for more complex meta-indexing (Izo

et al., 2021). Inasmuch as similar tools are still lack-

ing in many information systems used by the Brazil-

ian justice department. Integrating such tools into

local institutional systems could both enhance effi-

ciency by enabling precise and rapid retrieval of in-

formation from extensive document archives (Lima

et al., 2024) and allow one to perform complex in-

ferences on hitherto statistical parameters.

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0496-0272

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9244-157X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4033-8220

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5160-3280

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2066-7980

The judge’s decision-making landscape must

be minimally justified in their decision document.

Therefore, to apply a sentence s

i

, the judge must

justify it by presenting facts F , in other words, we

must find these elements, F

acts

→ s

i

, explicitly reg-

istered in the decision. F can be either the defen-

dant’s past criminal history f

1

, or the defendant’s

ties to the community f

2

, or the defendant’s employ-

ment history f

3

, or any other fact f

n

, or all together,

one may add to the decision’ description. Therefore,

F

acts

= { f

1

, f

2

, . . . , f

n

}, where F

acts

⊂ F , are the ex-

planation a judge gives to charge someone with a s

i

penalty.

Judges can also adopt the strategy of comparing

two, or more cases, to set up their decision. In this

case, a threshold is used to say that F

i

and F

j

– where

F

i

, F

j

⊂ F – are somehow similar to induce the same

sentence s

i

. By doing so, judges’ decisions become as

rational and clear as mathematics, aligning with so-

ciety’s expectation that judges remain impartial and

dispassionate (Maroney, 2011). Unfortunately, some

judges do not decide entirely on the record. They

add to the judgment decision their emotional feeling

266

Santos, A., Campos, G. S. Q., Griffo, C., Zandonade, E. and de Oliveira, E.

Explaining the Judges’ Decisions Criteria.

DOI: 10.5220/0013707500004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 1: KDIR, pages 266-274

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

and sympathy instead of the logic and strict descrip-

tion of the law. Other studies, discussed by (Rach-

linski and Wistrich, 2017), demonstrate that specific

religious values lead judges to decide certain kinds

of cases differently. Also, the authors in (Rachlinski

and Wistrich, 2017) examined various cognitive bi-

ases that may influence judges when issuing their ver-

dicts. Some are: (a) demographic characteristics of

judges. (b) relying heavily on intuitive reasoning and

not on facts, or even worse, relying on facts outside

the judicial records. In Brazil, we may include the

social class of the defendant as a bias factor on the ju-

dicial decisions. In theory, judges’ beliefs should not

override the original agreement expressed by the peo-

ple in the ordinary laws established under the Brazil-

ian Constitution.

The judge’s decision is the final administrative act

issued by the judicial system referring to facts dis-

puted by parts. Having this in mind, these documents

can be valuable instruments to assess the performance

of the system. However, to achieve this goal, we need

to build a better archive system to increase the acces-

sibility of these documents by attaching them to new

access points. Today’s accesses are based mainly on

the number of processes, the name of the parts, the

subject type in dispute, and keywords.

The extraction of the aforementioned metadata

may be straightforward using pattern recognition

strategies. In this work, we go beyond that by extract-

ing other information within these documents, such

as the names of other people mentioned, the dates

of the referenced events, and the time prescribed by

the court. More complex pieces of information re-

quire Natural Language Processing (NLP) (Manning

and Schuetze, 1999). To handle these more complex

extractions, this work incorporates prompt engineer-

ing techniques, which have proven effective in guid-

ing natural language models. This approach involves

the careful formulation of instructions for Large Lan-

guage Models (LLM)s, enabling a more efficient use

of their capabilities. Understanding how to construct,

refine, and strategically apply prompts is essential to

maximizing these models’ performance. Well-crafted

prompts allow the model to recognize subtle patterns,

such as temporal relationships and specific entities

(Schulhoff1 et al., 2024). Thus, prompt engineering

serves as a bridge between expert knowledge and arti-

ficial intelligence, expanding the practical application

potential of these models.

The contributions of this work are threefold. First,

we make publicly available a large dataset of court de-

cisions regarding the crimes discussed here. Second,

we organize these decisions into popular software fre-

quently used by archivists, such as AtoM

1

. Finally,

we analyze 769 decisions from 290 different equiv-

alents to USA district judges. We attempted to ex-

plain their statistical similarities and discrepancies by

extracting factual elements from their decision docu-

ments.

To present our proposal, we consider only four

types of crime: 1) Simple Theft, 2) Qualified Theft,

3) Robbery and 4) Drug Trafficking. We formed an

archive of 769 decisions from that issued by the S

˜

ao

Paulo Court of Appeal – (TJSP) in 2022 only.

This article is structured as follows. In Section

2, we discuss some recent works that will serve as

a basis for comparison with our proposal. In Sec-

tion 3, we present our proposal with an emphasis on

the efficient use of computational resources and arti-

ficial intelligence techniques aimed at the extraction

and structuring of legal data. In Section 4, we discuss

the experiments and results. Finally, we present our

conclusions in Section 5.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Advances in artificial intelligence and data analytics

have enabled computers to predict judicial decisions

by analyzing patterns in case law, judges’ rulings, and

legal reasoning.

Regarding judicial decision-making and the ap-

plication of technologies, the seminal Lawlor’s ap-

proach, developed by legal scholar Reed C. Lawlor,

arose in the 1960s. His work applied early computa-

tional logic to legal reasoning, using syllogistic struc-

tures to model how judges interpret facts and legal

rules. Lawlor’s method broke down judicial deci-

sions into discrete components - facts, legal princi-

ples, and outcomes - to identify predictable decision

pathways. From 70s to 90s, there were proposals to

combine the automation of legal reasoning and ex-

pert systems, such as: TAXMAN (McCarthy, 1977)

and FINDER (Tyree et al., 1987). Later, a compu-

tational breakthrough was introduced by (Susskind,

1998), and (Ashley, 1990) proposed a rule-based and

case-based reasoning paradigm, respectively. These

theoretical debates set the stage for computational

models aiming to replicate or predict judicial reason-

ing.

A paradigm shift from symbolic AI to data-driven

methods was proposed by (Bench-Capon and Sar-

tor, 2003), emphasizing the value-driven reasoning in

AI systems, and (Katz et al., 2017) applying tech-

niques such as machine learning, considering data-

1

https://www.accesstomemory.org/

Explaining the Judges’ Decisions Criteria

267

based decision-making but ignoring some contextual

factors.

Recent advances have pointed out on interdisci-

plinary innovations, for instance, NLP and Bench-

marking (Chalkidis et al., 2023), with LexGLUE

dataset standardizing legal NLP tasks; and topics as

ethical risks (Sourdin, 2021), such as the ethical con-

cerns about replacing judges with algorithms; biases

and hallucinations in automatic judicial decision mak-

ing ((Medvedeva et al., 2020): how evaluates biases

in AI predictions of human rights cases, and explain-

ability (how adapt AI for different legal systems).

In recent years, several projects have been sug-

gested to study how technology can be used in courts.

One of these projects is called ADELE. The ADELE

project tried to create a plan for using technology

to understand legal data. It focused on court deci-

sions to help analyze and process legal data more

effectively. The main goals were to enhance legal

data analysis, improve accessibility to case law in-

sights, and provide a structured approach to inter-

preting judicial decisions in these domains. The ap-

proaches applied were Natural Language Processing

(NLP) and machine learning (ML) to analyze court

decisions in Italian and Bulgarian case law, focus-

ing on Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) and Value

Added Tax (VAT). Key methods included text prepro-

cessing, named entity recognition (NER), and topic

modeling to extract legal concepts, classify cases, and

identify patterns. The project also utilized predictive

analytics and knowledge graphs to map legal relation-

ships and precedents, enabling structured analysis of

judicial decisions.

While these approaches offer valuable insights for

legal practitioners and policymakers, challenges re-

main, such as ensuring algorithmic transparency and

addressing biases in training data. Nevertheless, the

integration of computational methods into judicial

analysis represents a significant evolution in legal re-

search, bridging traditional doctrinal analysis with

data-driven forecasting.

As regards the legal nature of judicial decision,

its definition varies across legal traditions, for in-

stance, in Legal Positivism theory, a judicial decision

is ”the application of pre-existing rules to facts, de-

riving authority from the legal system’s hierarchy of

norms.” (Hart, 1961); in Legal Realism theory, ju-

dicial decisions are influenced by contextual factors

(e.g., judge’s worldview, societal values) beyond for-

mal rules (Fuller, 1958); in Legal Interpretivism, de-

cisions encompass principles (e.g., justice, fairness)

alongside rules, constructing a coherent moral nar-

rative (Dworkin, 1977), just to cite some legal doc-

trines.These theories reveal tensions between rule-

bound formalism and discretionary judgment, shap-

ing computational modeling attempts.

The Brazilian penal legal system is grounded in a

combination of legal theories (e.g., legal positivism,

social-critical critiques) that shape its substantive (Di-

reito Penal) and procedural (Direito Processual Penal)

dimensions. In this work, the scope of the Brazilian

theory of judicial decisions was limited to sentences,

which are a final court ruling that resolves the merits

of a case. Interlocutory decisions or provisional orders

were excluded from the scope.

A Judicial Sentence is issued by a competent

judge, who articulates the factual and legal basis for

the ruling. In terms of communicative acts, judicial

sentences are a subtype of institutional acts (Searle,

1995; Austin, 1975), i.e., an act requiring objective

and subjective validity conditions. Under the Brazilian

Code of Criminal Procedure (C

´

odigo de Processo Pe-

nal – CPP, Art. 381 to 383), to be considered as a valid

judicial sentence (sentenc¸a penal) must be signed and

dated, and necessarily containing 1) the identification

of all parties involved in the case, including their full

names or, when such information is unavailable, any

other details sufficient to establish their identity; 2)

must present a concise description (aka relat

´

orio) of

both the prosecution’s accusations and the defense’s

arguments, outlining the key claims and counterargu-

ments that frame the legal dispute; 3) the legal reason-

ing (aka fundamentac¸

˜

ao), which is the factual analy-

sis, the subsumption of the fact to the criminal type

(analyzing materiality, culpability, legal grounds). For

example, the defendant’s nocturnal entry into the vic-

tim’s property, captured on CCTV, satisfies the aggra-

vator of ’night-time’ under Art. 155, §4º.”; 4) the

dispositive part (aka dispositivo), containing the final

ruling, a clear decision on conviction or acquittal, the

penalty in case of convicted, and, in some cases, civil

liability. Also, there are some differences between

criminal type definitions as shown in Table 1.

The legal definitions and treatment of theft, rob-

bery, and drug trafficking reveal significant differ-

ences between Brazil’s civil law system and the United

States’ common law tradition. These distinctions re-

flect broader variations in legal philosophy, legislative

structure, and societal priorities.

In Brazil, simple theft is defined under Article 155

of the Penal Code as the unlawful taking of movable

property without consent and without violence, car-

rying a penalty of one to four years imprisonment.

The U.S. approach, guided by state statutes and the

Model Penal Code, focuses instead on the value of

stolen goods, distinguishing between petty theft (mi-

nor offenses) and grand theft (more serious crimes),

with penalties varying accordingly. Brazilian law fur-

KDIR 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

268

ther recognizes qualified theft, where aggravating fac-

tors such as breach of trust or nighttime commission

increase the sentence, while U.S. law lacks an exact

counterpart, instead enhancing penalties based on vic-

tim vulnerability or stolen property value.

Robbery in Brazil, as outlined in Article 157 of

the Penal Code, requires theft accompanied by vio-

lence or grave threat, punishable by four to ten years

in prison. The U.S. adopts a broader definition, where

any use of force or intimidation during theft consti-

tutes robbery, with penalties ranging from ten years

to life imprisonment, particularly in cases involving

firearms. This reflects a stricter stance on crimes in-

volving personal violence in the U.S. compared to

Brazil’s more narrowly defined thresholds for aggra-

vated theft.

Drug trafficking presents another area of contrast.

Brazilian law (Law 11.343/2006) criminalizes unau-

thorized production, transport, or sale of illicit drugs,

with sentences of five to fifteen years, while distin-

guishing between personal use and trafficking based

on quantity. The U.S., under federal law (21 U.S.C.

§ 841), emphasizes intent to distribute, imposing se-

vere penalties—often five to forty years—depending

on drug type and quantity, with mandatory minimum

sentences playing a prominent role.

These differences highlight how Brazil’s codified

legal system provides precise definitions and fixed

sentencing ranges, whereas the U.S. system’s flexibil-

ity allows for contextual adjustments based on judi-

cial interpretation and legislative enhancements. Un-

derstanding these distinctions is crucial for compara-

tive legal studies and cross-jurisdictional policy anal-

ysis.

3 THE METHODOLOGY

A judge’s decision statment contains numerous facts,

F

acts

, that may hold valuable information for some-

one in the future. However, it is impossible to predict

a priori which words, complex textual structures, or

other linguistic phenomena will be most useful to a

researcher, citizen, or archivist as their access points.

Therefore, we need enhanced tools and methodolo-

gies to efficiently adapt archival description structures

to meet users’ specific needs. The case study pro-

posed in this work is the evaluation of the behavior of

judges on sentencing. This information was not pre-

viously available to the information system for us to

process and perform various statistical analyses. For

that reason, we needed to extract them from the doc-

uments using modern artificial intelligence tools.

To protect the privacy of all parties involved in

the analyzed judicial documents, we adopted a rig-

orous anonymization process. All personal informa-

tion – including names of defendants, victims, wit-

nesses, and judges – was removed or replaced with

coded identifiers before applying the clustering al-

gorithms. Additionally, we ensured that the identi-

fiers used do not allow reverse re-identification, even

through cross-referencing analysis. This careful ap-

proach is especially important in grouping judges by

sentencing patterns, where we take additional mea-

sures to prevent any risk of individual exposure.

3.1 The Prompting Engineering

Strategy

To construct the database, structured information

was automatically extracted from judicial rulings, in-

cluding case number, category, district, court divi-

sion, presiding judge, imposed sentences (base, pro-

visional, and final), as well as judicial circumstances

and aggravating or mitigating factors such as recidi-

vism, use of weapons, attempt, voluntary confession,

and characteristics of both the defendant and the vic-

tim. The extraction process was carried out with

the assistance of the Qwen 2.5-32B-Instruct language

model (Qwen et al., 2025), an open-source model

with 32 billion parameters, run locally. The choice of

this dense version of the model ensured greater con-

trol over processing, preservation of the confidential-

ity of judicial decisions, and advanced performance

in tasks involving legal language understanding and

structured data handling. A prompt was developed to

traverse all decisions, identifying sentences and cor-

rectly linking them to the respective individuals, as

some rulings involve multiple defendants. This step

was essential to properly structure the data, enabling

subsequent analyses of judicial behavior in sentenc-

ing decisions.

The prompt followed a zero-shot approach, in

which the model is guided solely by natural language

instructions without being provided with prior input-

output examples (Boyina et al., 2024). This technique

allows for quick adaptation to new texts and tasks,

although it may face limitations in more complex or

ambiguous contexts, as is often the case with judicial

rulings. For this reason, few-shot variations were also

tested, incorporating concrete examples to guide the

model regarding the expected format and the type of

information to be extracted (Huang and Wang, 2025).

The combination of these approaches proved effec-

tive in increasing the accuracy and consistency of the

extraction process, contributing to the creation of a

reliable and reusable dataset for empirical analyses of

the criminal justice system.

Explaining the Judges’ Decisions Criteria

269

Table 1: Comparative analysis of theft, robbery, and drug trafficking: Brazil vs. U.S.

Crime Type Brazilian Law U.S. Law Key Distinctions

Simple Theft Definition: Unlawful taking of

movable property without violence

or consent (Art. 155, CP).

Penalty: 1–4 years + fine.

Definition: Unlawful taking with

intent to deprive the owner perma-

nently (no force).

Penalty: Petty theft (≤6 months)

to grand theft (1–3 years, state-

dependent).

Brazil focuses on property

type (movable), U.S. prioritizes

property value thresholds.

Qualified Theft Definition: Theft + codified aggra-

vators (e.g., breach of trust, night-

time; Art. 155, §4º).

Penalty: 2–8 years.

No standalone category; aggrava-

tors (e.g., victim age, high value) el-

evate to felony theft.

Brazil’s aggravators are explicit

in law, U.S. uses contextual en-

hancements.

Robbery Definition: Theft with vio-

lence/grave threat (Art. 157, CP).

Penalty: 4–10 years (increased if

armed).

Definition: Theft by

force/intimidation (e.g., armed

robbery; 18 U.S.C. § 1951).

Penalty: 10 years–life (varies by

state).

Brazil requires grave

threat; U.S. accepts any

force/intimidation.

Drug Traffick-

ing

Definition: Unauthorized pro-

duction/sale of drugs (Law

11.343/2006, Art. 33).

Penalty: 5–15 years.

Definition: Manufac-

ture/distribution with intent to

distribute (21 U.S.C. § 841).

Penalty: 5–40 years (mandatory

minimums apply).

Brazil distinguishes trafficking

from personal use by quantity.

U.S. focuses on proven intent.

4 EXPERIMENTS AND RESULTS

The experiments carried out in this work show the be-

havior of a set of district judges from S

˜

ao Paulo, the

biggest city in Brazil, with regard of four diffrent type

of crimes (see Section 2). Initially, we evaluated the

best statistical distribution to characterize the Simple

Theft sample of 99 sentences. In Table 2, we show

the statistics for these sample sentences issued in our

dataset for that type of crime.

Table 2: The simple theft statistics.

Simple Theft

Base Penalty Final Penalty

year month year month

minimum 1.00 12.00 0.33 4.00

average 1.20 14.37 1.16 13.96

σ 0.33 3.99 0.58 6.95

median 1.17 14.00 1.17 14.00

maximum 3.00 36.00 5.00 60.00

Based on the facts presented by the state’s attor-

ney and the defendant, the judge may determine a

base penalty in their decision (refer to the first and

second columns in Table 2). This base penalty serves

as the starting point, while the final penalty (see the

third and fourth columns) results from adjustments –

either increases or reductions – based on the evalua-

tion of previously described factors. The values in the

second column indicate that the minimum sentence

is one year (365 days), while the maximum is three

years. The average lies close to the center of this in-

terval. Adding further statistical insight, the standard

deviation (σ = 0.33) is less than one year, indicating

that for this type of crime, the variation around the

average sentencing is relatively small. The third col-

umn shows similar figures but in months, considering

all months with 30 days. These are two usual ways

for professionals in the justice domain to deal with

sentences. Above all, one can notice that all the me-

dian figures among year and month columns are very

similar to the average values, suggesting a symmetric

normal-curve.

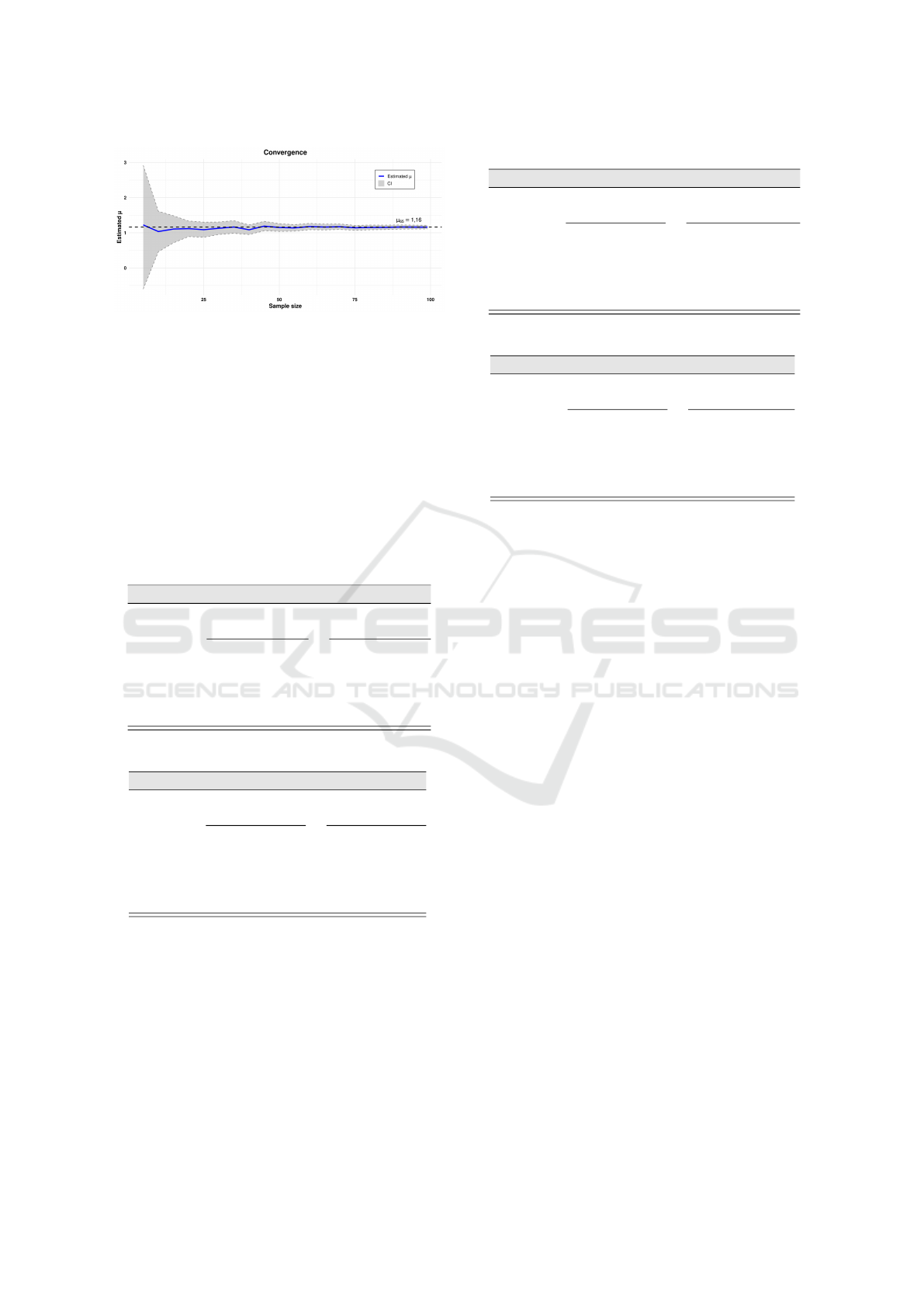

Besides the previous deterministic experiments,

we also carried out a different approach to estimate

the same value discussed in Table 2 by applying the

Probabilistic Programming (PP) technique with Stan

language (Carpenter et al., 2017). PP is an approx-

imation strategy, therefore the values of average and

σ are not exactly the same of that calculated by the

deterministic strategies in Table 2. Currently built

within many modern languages, such as Python and

R, PP uses an efficient engine to sample and re-sample

to find the converging parameters to find a statistical

distribution model for a given problem (Gelman et al.,

2013). Nevertheless, we show the convergence of the

approximated averages, for years, using a set of dif-

ferent samples in Figure 1.

The convergence in Figure 1 pointed out the aver-

age estimated by our PP approach. The approximated

average given by the PP tool is 1.16, and the stan-

dard deviation is 0.59 at the level of the 65 sample

items, much similar to that provided by the determin-

KDIR 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

270

Figure 1: Convergence of years average for Simple Theft.

istic procedure in Table 2. Besides, note that the cred-

ible interval shown in Figure 1 by the light gray area

around the convergence line is narrowing as we in-

crease the sample. This straight light gray area tells

us we do not need a larger sample than 99 random

sentences to conclude the average is 1.16 with 95%

certainty.

The following Table 3 up to Table 6 present statis-

tics for all four crimes considered in this study, each

with a sufficient sample size to ensure that the average

falls within a 95% credible interval.

Table 3: The simple theft statistics.

Simple Theft – 276 sample

Base Penalty Final Penalty

year month year month

minimum 0.29 3.50 0.22 2.67

average 1.62 19.48 1.68 20.16

σ 0.69 8.31 1.00 12.03

median 1.25 15.00 1.33 16.00

maximum 4.67 56.00 5.83 70.00

Table 4: The qualified theft statistics.

Qualified Theft – 174 sample

Base Penalty Final Penalty

year month year month

minimum 1.00 12.00 0.67 8.00

average 2.18 26.15 2.31 27.68

σ 0.65 7.78 1.13 13.59

median 2.33 28.00 2.04 24.43

maximum 4.75 57.00 7.58 91.00

Each table describes a model to explain mathe-

matically its respective crime sentencing behavior by

the population of judges of that district. With these

prior models, we can compare and contrast judicial

patterns across different districts and states in Brazil.

In addition, this framework allows for discussions on

whether these models reflect local culture and social

norms or whether interventions might be necessary to

influence or redirect judicial behavior.

A particularly interesting statistical analysis in

this context is the analysis of variance (ANOVA),

Table 5: The robbery statistics.

Robbery – 149 sample

Base Penalty Final Penalty

year month year month

minimum 1.00 12.00 0.58 7.00

average 4.57 54.82 7.52 90.25

σ 0.78 9.35 4.24 50.90

median 4.67 56.00 6.67 80.00

maximum 6.67 80.00 36.00 432.00

Table 6: The drug trafficking statistics.

Drug Trafficking – 170 sample

Base Penalty Final Penalty

year month year month

minimum 2.00 24.00 1.62 19.43

average 5.48 65.77 4.63 55.55

σ 0.87 10.41 2.47 29.69

median 5.00 60.00 1.33 16.00

maximum 8.00 96.00 9.72 116.67

which revealed significant differences in the average

sentences among the crimes evaluated (simple theft,

qualified theft, robbery, and drug trafficking), with an

F distribution value of 144.14 and p < 0.0001. This

result shows that at least one group differs from the

others. Tukey’s post hoc test revealed that sentences

for robbery are significantly higher than for the other

crimes, and that drug trafficking also has higher aver-

age sentences compared to both simple and qualified

theft. The only comparison without a significant dif-

ference was between simple theft and qualified theft,

indicating that, in terms of average sentencing, these

two types of theft are treated similarly in the dataset

analyzed.

These results indicate a clear gradation in the

severity of sentences, with robbery receiving the high-

est penalties, followed by drug trafficking, and finally

theft-related offenses. Robbery stands out not only for

having higher average sentences but also for greater

variability, including extreme cases with very long

sentences. Drug trafficking also shows a high me-

dian and greater dispersion compared to the theft cate-

gories. In contrast, simple theft and qualified theft ex-

hibit similar patterns, with close medians and lower

variability, reinforcing the lack of significant differ-

ence between them identified in the statistical analy-

sis.

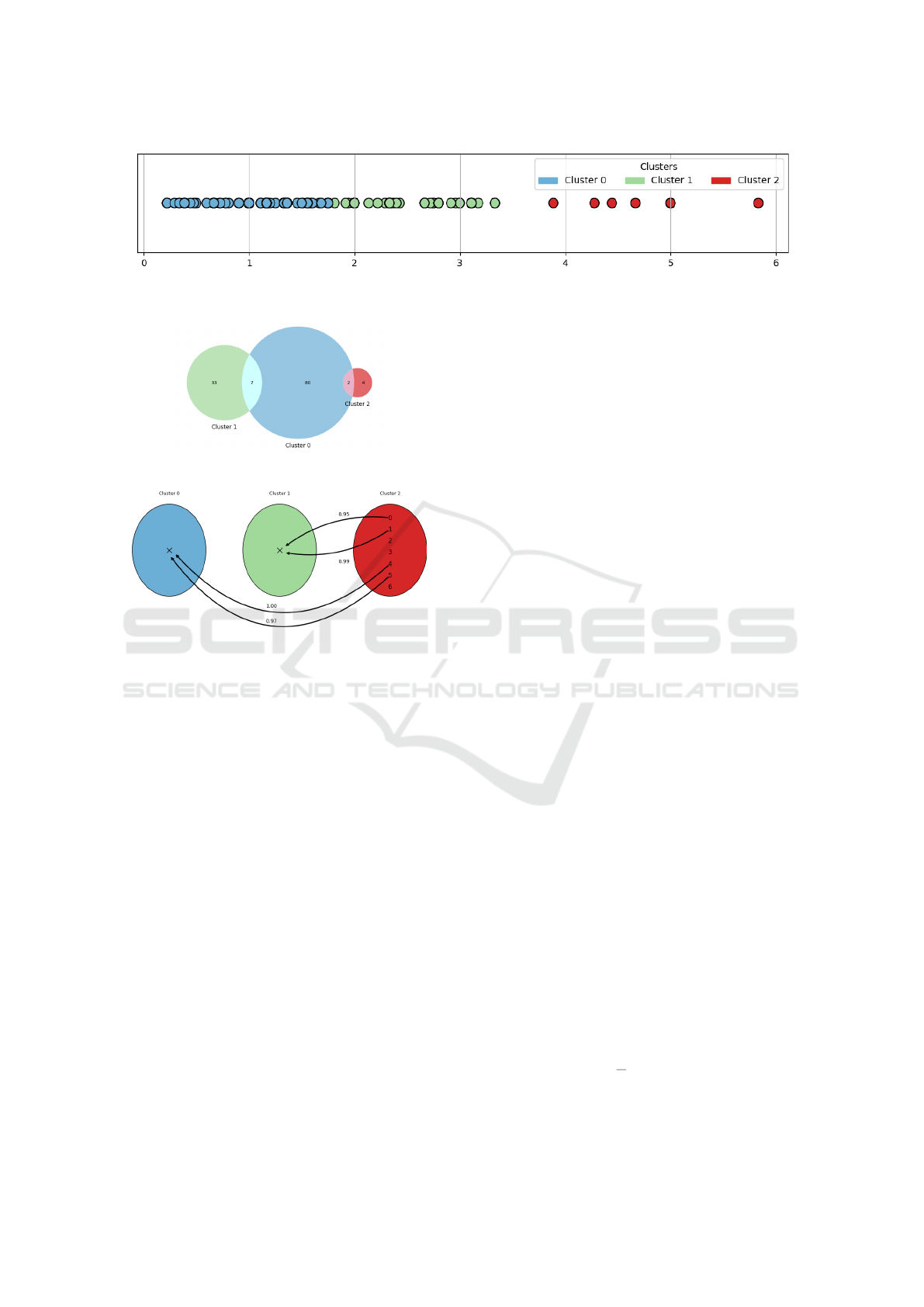

Note that within this dataset, there are 290 judges

who, through their sentencing behavior, contributed

to the models described by the parameters in the pre-

vious tables. In Figure 2, three clusters were defined

with the aim of identifying patterns of similarity in

sentencing, considering only those judges who sen-

tenced this type of crime. The choice of the num-

Explaining the Judges’ Decisions Criteria

271

ber of clusters was guided by quantitative criteria, ex-

tracted during the automated clustering process. The

K-Means algorithm was used, with its configuration

driven by multiple internal validation indices, such as

the Silhouette Score (SS), the Calinski-Harabasz in-

dex (CHS), and the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE). The

combination of these indicators allowed identifying

the three-cluster configuration as the most consistent

in terms of group separation and internal cohesion of

the data. Thus, the resulting structure reflects clusters

based on objective quality metrics.

In Figure 2, the N(µ

ST

l

, σ

ST

l

) = N

ST

l

(1.08, 0.37)

normal distribution is a model to describe the

first group of judges on the left. On the right,

N(µ

ST

r

, σ

ST

r

) = N

ST

r

(4.72, 0.58) explains the second

group. Each model may account for the sentencing

patterns observed among a particular group of judges

in relation to this type of crime. The range of val-

ues of sentencing by these judges shows, hopefully,

how different the circumstances faced by these judges

for sentencing they did. Nonetheless, we are not yet

looking into their sentencing text to combine the im-

plication of their decision text and the time assigned

to the sentence. We expect that the similar decision

text should lead to the same time assigned to the sen-

tence. These models also allow us to identify an un-

known judge by one of these patterns by testing the

judge characteristics under the the null hypothesis, to

a previous known N

ST

(µ, σ). To build the models in

Figure 2, we clustered all sentences’ values in years

and fractions because of months and days. That re-

sulted in 51 decisions in the left cluster and 7 in the

right cluster out of 276 decisions in total of this type

of crime. The other sentences are in the clusters be-

tween these extreme ones.

So far, we illustrated our constructed mathemati-

cal structure only with N

ST

(µ, σ) models, for simple

theft. However, we have also built similar structures

for: (a) N

QT

(µ, σ), qualified theft; (b) N

R

(µ, σ), rob-

bery; and (c) N

T

(µ, σ), drug trafficking.

The devised structures allow us to quickly search

for the seven sentences, but one is overlapping an-

other, placed on the right in Figure 2 as potential out-

liers sentences of this type of crime. We can also iden-

tify the judge, or judges, who have issued the court

sentence in the N

ST

r

(µ, σ) cases. Only six different

judges issued those sentences, as shown in Figure 3.

Among them, other twenty judges also issued sen-

tences in different clusters. This unveils a very par-

ticular pattern of sentencing of these judges, which

we can now look into the reasons why that occurred.

Similarly, we identified some outlier sentences for

qualified theft in Figure 3. Using the same quantity of

four clusters previously applied to simple theft, four

judges handed down sentences in the highest time-

value group, while the remaining twenty were dis-

tributed among the other clusters.

To sum up, although the judges’ decision texts dif-

fered from one another – explaining the variation in

sentencing durations – some decisions appeared out

of place or inconsistent with their respective clusters,

as depicted in Figure 4.

We note that sentence 0, currently in Cluster 2,

shares 95% similarity with Cluster 2. Similarly, sen-

tence 1 shows 99% similarity with the same cluster.

This suggests that both sentences could reasonably

belong to Cluster 1, but are assigned to Cluster 2 due

to their penalty values. Likewise, sentences 4 and 5

show strong similarity to those sentences in Cluster

1 – 100% and 97%, respectively. These sentences

are considered outliers for this type of crime. Simi-

lar cases are also found on another type of crimes.

5 CONCLUSION

This work proposes the use of LLMs to extract com-

plex information from legal texts, optimizing both

archival description and the progress of legal pro-

ceedings through automation and semantic analysis.

Unlike traditional approaches that focus only on ele-

ments such as case numbers or involved parties, our

method analyzes the full text to identify named en-

tities, allowing inferences about judges’ behavior in

their decisions.

The analysis focused on the duration of sentences

to identify behavioral patterns, particularly in extreme

cases. Empirical studies (Rachlinski and Wistrich,

2017) show that judicial decisions may be influenced

by subjective factors—such as stereotypes or emo-

tional states—rather than strictly legal reasoning.

One of the key findings is the connection between

Figures 2, 3, and 4, all related to the crime of simple

theft. Figure 2 presents the distribution of sentences

across three distinct clusters, based on duration. Fig-

ure 3 retains the same sentences, now grouped by

the judges who issued them, with colors preserved

to represent the same clusters as in Figure 2. Fig-

ure 4, in turn, focuses on the sentences originally clas-

sified under cluster 2, redistributing them among the

same three clusters—based on the textual similarity of

each sentence to the centroids of these groups—while

maintaining the same colors for comparison. This se-

mantic comparison allows the user not only to verify

thematic compatibility between the sentence and the

reference group, but also to justify the inferred sen-

tence based on observed linguistic patterns. The anal-

ysis reveals that some decisions, although grouped by

KDIR 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

272

Figure 2: Clustering judges based on their sentencing to time – Simple Theft.

Figure 3: Simple Theft.

Figure 4: Clusters according to their texts – Simple Theft.

sentence length, are linguistically closer to the dis-

courses of other clusters. This suggests inconsisten-

cies in reasoning and possible influence of extralegal

criteria in sentencing, even in legally homogeneous

cases.

The proposed tool proved effective in detecting

linguistic patterns and behavioral anomalies. How-

ever, discrepancies were observed between the terms

identified automatically and those recognized by legal

experts. As future work, we propose the development

of ontologies to define metadata types and synonyms,

the segmentation of clusters into more homogeneous

subgroups, and the filtering of sentences with low se-

mantic cohesion. We also suggest using embeddings

or legal dictionaries to normalize linguistic variations

and reduce noise in the analyses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Jos

´

e Jesus-Filho and Julio Trecenti

for their support and for providing the software that

enabled the collection and organization of data from

the S

˜

ao Paulo Court of Justice (Jesus-Filho and Tre-

centi, 2020).

REFERENCES

Ashley, K. D. (1990). Modeling Legal Argument: Reason-

ing with Cases and Hypotheticals. MIT Press, Cam-

bridge, MA.

Austin, J. L. (1975). How to do things with words. Harvard

university press.

Bench-Capon, T. J. M. and Sartor, G. (2003). A model of

legal reasoning with cases incorporating theories and

values. Artificial Intelligence, 150(1–2):97–143.

Boyina, K., Reddy, G. M., Akshita, G., and Nair, P. C.

(2024). Zero-shot and few-shot learning for telugu

news classification: A large language model approach.

In 2024 15th International Conference on Computing

Communication and Networking Technologies (ICC-

CNT), pages 1–7.

Carpenter, B., Gelman, A., Hoffman, M. D., Lee, D.,

Goodrich, B., Betancourt, M., Brubaker, M., Guo, J.,

Li, P., and Riddell, A. (2017). Stan: A Probabilistic

Programming Language. Journal of Statistical Soft-

ware, 76(1).

Chalkidis, I., Jana, A., Hartung, D., Bommarito, M., An-

droutsopoulos, I., Katz, D. M., and Aletras, N. (2023).

Lexglue: A benchmark dataset for legal language un-

derstanding in english. In Proceedings of the 61st

Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational

Linguistics, pages 1–15.

Dworkin, R. (1977). Taking Rights Seriously. Harvard Uni-

versity Press, Cambridge, MA.

Fuller, L. L. (1958). Positivism and fidelity to law—a reply

to professor hart. Harvard Law Review, 71(4):630–

672.

Gelman, A., Carlin, J., Stern, H., Dunson, D., Vehtari, A.,

and Rubin, D. (2013). Bayesian Data Analysis. Chap-

man and Hall/CRC, 3 edition.

Hart, H. L. A. (1961). The Concept of Law. Oxford Univer-

sity Press, Oxford.

Huang, D. and Wang, Z. (2025). Logical reasoning with

llms via few-shot prompting and fine-tuning: A case

study on turtle soup puzzles. In 2025 IEEE Sympo-

sium on Computational Intelligence in Natural Lan-

guage Processing and Social Media (CI-NLPSoMe

Companion), pages 1–5.

Izo, F., Oliveira, E., and Badue, C. (2021). Named Entities

as a Metadata Resource for Indexing and Searching

Information. In 21

th

International Conference on In-

telligent Systems Design and Applications – (ISDA),

volume 418, pages 838–848, On the WWW. Springer

International Publishing.

Explaining the Judges’ Decisions Criteria

273

Jesus-Filho, J. and Trecenti, J. (2020). Coleta e

Organizac¸

˜

ao de Dados do Tribunal de Justic¸a de S

˜

ao

Paulo. S

˜

ao Paulo, SP.

Katz, D. M., Bommarito, M. J., and Blackman, J. (2017).

A general approach for predicting the behavior of

the supreme court of the united states. PLOS ONE,

12(4):e0174698.

Lima, J., Santos, A., Almeida, E., Pirovani, J., and

de Oliveira, E. (2024). Extrac¸

˜

ao de Metadados para

um Grande Arquivo de Decis

˜

oes Judiciais: Uma

Abordagem com Intelig

ˆ

encia Artificial. In X CNA –

Congresso Nacional de Arquivologia, Salvador, BA.

CNA.

Manning, C. D. and Schuetze, H. (1999). Foundations of

Statistical Natural Language Processing. The MIT

Press, New York, NY, 1

st

edition.

Maroney, T. A. (2011). The Persistent Cultural Script of

Judicial Dispassion. Calif. L. Rev., 99:629.

McCarthy, L. T. (1977). Reflections on taxman: An ex-

periment in artificial intelligence and legal reasoning.

Harvard Law Review, 90(5):837–893.

Medvedeva, M., Vols, M., and Wieling, M. (2020). Using

machine learning to predict decisions of the european

court of human rights. Artificial Intelligence and Law,

28(2):237–266.

Qwen, Yang, A., Yang, B., Zhang, B., Hui, B., Zheng, B.,

Yu, B., Li, C., Liu, D., Huang, F., Wei, H., Lin, H.,

Yang, J., Tu, J., Zhang, J., Yang, J., Yang, J., Zhou, J.,

Lin, J., Dang, K., Lu, K., Bao, K., Yang, K., Yu, L.,

Li, M., Xue, M., Zhang, P., Zhu, Q., Men, R., Lin, R.,

Li, T., Tang, T., Xia, T., Ren, X., Ren, X., Fan, Y., Su,

Y., Zhang, Y., Wan, Y., Liu, Y., Cui, Z., Zhang, Z., and

Qiu, Z. (2025). Qwen2.5 technical report.

Rachlinski, J. J. and Wistrich, A. J. (2017). Judging the

Judiciary by the Numbers: Empirical Research on

Judges. Annual Review of Law and Social Science,

13(1):203–229.

Schulhoff1, S., Ilie, M., Balepur, N., Kahadze, K., Liu,

A., Si, C., Li, Y., Gupta, A., Han, H., Schulhoff,

S., Dulepet, P. S., Vidyadhara, S., Ki, D., Agrawal,

S., Pham, C., Li, G. K. F., Tao, H., Srivastava, A.,

Costa, H. D., Gupta, S., Rogers, M. L., Goncearenco,

I., Sarli, G., Galynker, I., Peskoff, D., Carpuat, M.,

White, J., Anadkat, S., Hoyle, A., and Resnik, P.

(2024). The Prompt Report: A Systematic Survey of

Prompting Techniques.

Searle, J. R. (1995). The construction of social reality. Si-

mon and Schuster.

Sourdin, T. (2021). Judge v. robot? ai and judicial decision-

making. University of New South Wales Law Journal,

44(3):1110–1133.

Susskind, R. (1998). The future of law: facing the chal-

lenges of information technology. Oxford University

Press.

Tyree, A., Greenleaf, G., and Mowbray, A. (1987). Legal

Reasoning: The Problem of Precedent. In Gero, J. S.

and Stanton, R., editors, Artificial Intelligence Devel-

opments and Applications, pages 231–245.

KDIR 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval

274