Knowledge Management in Finnish Comprehensive Security

Ecosystem

Jussi Kosonen

Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä, Seminaarinkatu 15, FI-40014, Finland

Keywords: Comprehensive Security, Knowledge Networks, Knowledge Management, Collaboration.

Abstract: Society is exposed to a wide range of threats that can jeopardise the continuity of organisations and the

security of citizens. In previous years, deliberate hybrid influence from authoritarian countries has increased

significantly. Finland's comprehensive security is a cooperative concept for implementing preparedness and

crisis management. Organisations involved in comprehensive security require knowledge to prepare and

respond appropriately to crises. This study aimes to determine how knowledge is managed within the Finnish

comprehensive security knowledge network. A theory-guided mixed methods study investigated the security-

related knowledge management practices of 54 diverse Finnish organisations involved in comprehensive

security. The study identifies knowledge management in a four-layer architecture: institutional, organisational,

interaction, and knowledge layers, all of which need to be aligned to facilitate effective knowledge

management. According to the findings, networked knowledge management works partly well, but there is

potential for improvement in the breadth and depth of knowledge-sharing. This study suggests proposals for

the development of knowledge networks and management for comprehensive security.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Finnish Security Strategy defines comprehensive

security as the foundation of national resilience, in

which vital societal functions are maintained through

cooperation between public, private, and third-sector

organisations. The preparedness within The Finnish

comprehensive security ecosystem is based on

legislation, agreements, and voluntary contributions.

Multifaceted threats create challenges for societal

security and resilience caused by state, non-state and

environmental factors. The unpredictable nature of

these threats complicates forecasting and

preparedness. Knowledge and situational

understanding are key factors for efficient

preparedness and crisis management. (Finnish

Security Committee, 2025) This study aims to answer

an under-researched question: How knowledge is

managed within Finland's comprehensive security

ecosystem?

Hybrid threats refer to hostile actors' efforts to

undermine society by exploiting vulnerability across

domains. State actors pursue political objectives

through hybrid activities (Galeotti, 2019), with

warfare being the ultimate option for authoritarian

states. Organisations face constant risks, such as

cyber-physical vulnerabilities, information

manipulation, and intelligence collection. Artificial

intelligence has expanded hybrid capabilities,

especially in the information domain (Yan, 2020).

According to a Finnish survey, half of the large

enterprises considered themselves targets of hybrid

activities. Because many of them fall out of

systematic security knowledge sharing, 96 % of

businesses would expect better knowledge from

officials (Vesterinen, 2022).

Knowledge is a key component in comprehensive

security. A diverse comprehensive security

ecosystem requires networked knowledge

management practices to facilitate situational

awareness and decision making. Since responsibility

is shared without one central organisation,

information exchange practices and collaboration at

the international, national, regional, and local levels

are crucial. Organisations can enhance their

adaptability to security threats by fostering

knowledge sharing and continuous learning within

the network. Sufficient security-related knowledge

enables proactive preparedness. Synergy between

comprehensive security and knowledge management

enables organisations to leverage explicit and tacit

knowledge in their preparedness and activities.

370

Kosonen, J.

Knowledge Management in Finnish Comprehensive Security Ecosystem.

DOI: 10.5220/0013676400004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

370-377

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

2 RELATED LITERATURE

2.1 Knowledge Networks

Knowledge management (KM) is a methodical

approach to creating, sharing, and applying

knowledge to gain competitive advantage and fulfil

organisational goals (Nicolas, 2004). Several studies

have identified significant benefits of well-

functioning knowledge management (Andreeva &

Kianto, 2012; Kebede, 2010; Rousseau, 2006).

Knowledge networks are groups of connected

people or organisations that store knowledge and

interact with knowledge tasks. (Phelps et al., 2012).

The structure encompasses diverse participants

within defined boundaries, with participants

understanding their roles in making the ecosystem

less vulnerable to external pressures (Cobben et al.,

2022). The key attributes of knowledge ecosystems

include dynamic value creation from exchanges

between organisations and ecosystem management

(Van der Borgh et al., 2012). Ecosystems include

techniques and platforms enabling knowledge

development, transfer and utilisation, with their

primary characteristic being ability to produce new

insights and solutions (Vodă et al. 2023).

Organisations face a paradox when protecting and

sharing knowledge, highlighting the need to manage

cross-boundary knowledge flows within knowledge

ecosystems (Loebbecke et al. 2016). According to the

information-processing view by Premkumar et al.

(2005), organisations have two strategies for

managing uncertainty: developing protective buffers

or enhancing information-processing capabilities to

improve knowledge flow. Öberg and Lundberg

(2022) noted that knowledge ecosystems operate

through structure and openness mechanisms. The

structure involves linear knowledge transfer through

formal channels, whereas content development is

collaborative. A functioning ecosystem requires

parties to reach a sufficient understanding before

collaboration can occur.

Knowledge sharing within a network facilitates

three processes: knowledge creation, transfer, and

adoption (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). This sophistication

varies across organisations. Nunamaker et al. (2001)

categorised these capabilities into three levels: Level

1 represents individualistic and uncoordinated

efforts; Level 2 shows emerging coordination that

remains ad hoc; and Level 3 exhibits concerted

capabilities where teams work through repeatable,

adaptive processes. Collaborative dynamics affect

inter-organisational knowledge sharing positively or

negatively. Huxham (2003) highlighted collaborative

advantage, signifying gains from joint efforts, and

collaborative inertia, referring to unsatisfactory

outcomes. A collaborative advantage occurs when a

collective achieves what individuals cannot achieve.

However, the results often seem minimal, suggesting

that organisations must weigh benefits against

investments.

2.2 Attributes of Knowledge

Knowledge is a resource that can be transferred

within a knowledge network. The Data-Information-

Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy is a

foundational framework for knowledge management

that illustrates cognitive transformations. This

suggests that wisdom emerges from collecting data,

transforming it into information, refining it into

knowledge, and combining it with experience

(Ackoff, 1999). The DIKW model implies that each

level builds on the previous one: data are raw facts,

information includes context, knowledge applies

information through experience, and wisdom is the

judicious application of knowledge. However, this

concept has been criticised. Tuomi (1999) argued

data emerge only after meaningful structures and

semantics are established through existing

knowledge. This suggests that the DIKW model

enhances the interplay of technical solutions and

social processes, enabling users to make sense of

shared meanings within organisational contexts.

Explicit and tacit knowledge may be

distinguished. While explicit knowledge can be

documented and shared through formal channels,

tacit knowledge represents a deeply internalised

understanding that individuals possess, but cannot

easily articulate. (Polanyi, 1958; Nonaka, 1994).

Knowledge creation occurs through a dialoque

between tacit and explicit knowledge, ultimately

crystallising into concrete forms. The SECI model,

named after Socialisation (tacit-tacit), Externalisation

(tacit-explicit), Combination (explicit-explicit), and

Internalisation (explicit-tacit), identifies knowledge

development as a continuous cycle between tacit and

explicit knowledge in which knowledge is amplified

and expanded across individual, group, and

organisational levels (Nonaka & Toyama, 2003). This

principle may also be applied in the inter-

organisational context of knowledge transfer (Alavi

& Leidner, 2001). Such knowledge transfers can

occur bilaterally or multilaterally within the

knowledge network.

Knowledge Management in Finnish Comprehensive Security Ecosystem

371

3 METHODOLOGY

A theory-guided, qualitative, mixed-methods

approach was selected to answer the research

question. The three main phases of the study were

establishing a theory-based framework, interviews,

and a survey. The phased approach enabled iterative

development of understanding between the phases.

The research design was driven by diverse research

population and complex phenomena. The choice for

mixed-methods research aimed to combine the

strengths of both research traditions, allowing for a

deeper understanding of phenomena (Venkatesh,

2016; Plano Clark, 2019).

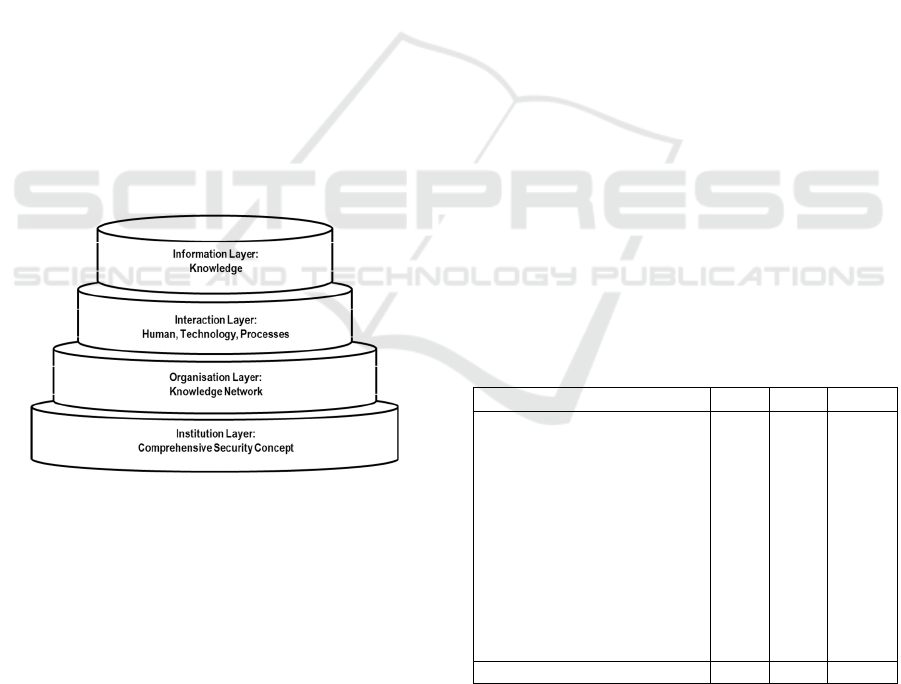

Theories related to inter-organisational

knowledge management provided a starting point for

the study, based on which a 4-layer model (Figure 1)

was established as a framework. The base layer,

named as the institution layer, encompasses a

comprehensive security ecosystem and state-level

regulation. The subsequent network layer comprises

various organisations operating in a hybrid-threat

environment. The interaction layer, as the third layer,

facilitates the exchange of knowledge between

organisations. Finally, the fourth layer pertains to the

knowledge itself, which is transferred and developed

among organisations.

Figure 1: 4-Layer Knowledge Management Framework.

The data were collected in two phases: interviews

and a survey. The data collection also included other

elements aimed at a larger research project, the results

of which are reported separately. The organisations

and representatives for interviews were selected in

such a way that they represented each of the seven

vital functions of society, as defined in the Security

Strategy. In the first data collection phase (Ph1),

interview requests were sent to 17 key persons, 15 of

whom agreed to be interviewed, resulting in a

response rate of 88 %. The interviews were semi-

structured and the questions were guided by relevant

knowledge management theories. The interview

consisted of 20 questions tailored to explore each

organisation’s knowledge management practices and

knowledge exchange with other organisations.

Interviews were conducted face-to-face or on the

phone between November 2022 and October 2024,

each lasting 45–70 minutes. The main questions

related to this study were: “How does your

organisation obtain security-related knowledge?” and

“Describe your organisations knowledge transfer

with other organisations”.

The interviews were transcribed and saved in

Microsoft Excel. Theory-guided content analysis

focused on identifying and coding content related to

the established theoretical 4-layer model. As Hsieh

and Shannon (2005) noted, directed content analysis

results can support, contradict, or add to this theory.

The second phase of data collection (Ph2) aimed

to add reliability and generalisability to the results of

the interviews. The survey was conducted using an

electronic Webropol questionnaire distributed via

email to 126 respondents. The respondents were

identified as important members of organisations

involved in the Finnish comprehensive security

ecosystem. The survey was conducted in March 2025

and received 39 responses, yielding a response rate of

31 %. The questionnaire contained 106 multiple-

choice and seven open-ended questions. The main

questions contributing to this study focused on the

intensity, means, and content of transfer between

organisations, as well as facilitators and barriers for

interaction. Table 1 presents the two phases of data

collection.

Table 1: Sample (n=54) divided by the vital functions of

society (Security Committee, 2025).

Function Ph1 Ph2 Total

Mental crisis resilience

Defense capability

Internal security

Leadership

International and EU

activities

Economy, infrastructure and

security of supply

Functional capacity of the

population and services

3

2

3

2

1

2

2

5

6

1

2

2

16

7

8

8

4

4

3

18

9

Total n=15 n=39 n=54

The second dataset included both qualitative and

quantitative data; however, the analysis was

qualitatively oriented. Identified themes and findings

from the previous phase were used as a baseline. The

content of the open-ended questions was coded using

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

372

the same process as in Ph1 and added to prior

findings. Quantitative data were referenced to the

interview results, partly confirming the previous

findings. Completely new themes did not emerge

from the second dataset. In conclusion, the results

were improved by combining the interviews and

complementing survey responses.

4 RESULTS

The analysis of the research data revealed complex

knowledge flows within Finland's comprehensive

security ecosystem. Some distinct but interconnected

themes emerged from the data, demonstrating

networked and often self-synchronising practices

rather than hierarchical knowledge flow. Formal

structures were complemented by informal

relationship-based exchanges. The findings express

both multi-source integration and adaptability, as well

as weaknesses and risks. The main findings are

presented next based on the 4-layer model.

4.1 Knowledge Network

The Finnish comprehensive security ecosystem

comprises diverse organisations with varying security

relevance. Every organisation’s knowledge

requirements are unique, as are their connectness in

the knowledge network. According to the findings,

society's vital functions express domain-specific

networks to some extent. More importantly, four

cross-domain categories were identified: security

authorities, administration, critical infrastructure, and

other organisations. All these categories are also

internationally connected.

Centrality and depth of security-related

knowledge varied significantly according to these

categories.

The central actors in a comprehensive security

knowledge ecosystem are security authorities. These

organisations possess and provide the most relevant

security-related knowledge in Finland. As many

respondents mentioned, “We are dependent on the

knowledge of security authorities”. The second

category comprises governmental organisations,

including ministries and agencies, that perform

statutory tasks within their respective domains while

also maintaining comprehensive security obligations.

The findings indicate that governmental

organisations have systematically organised their

information exchanges, establishing regular and well-

institutionalised interagency networks.

The third category consists of organisations that

sustain the critical functions of society. In Finland,

approximately 1,500 organisations, predominantly

from the private sector, hold this designation

(National Emergency Supply Agency, 2025). These

entities seek to maintain profitable operations while

simultaneously fulfilling their statutory or contractual

roles in supply security.

Fourth, a large majority of other organisations,

including numerous businesses, municipalities, and

third-sector organisations, fall outside systematic

security knowledge exchange.

It is also worth mentioning that domain-specific

subnetworks overlap all these categories. They are

particularly important in facilitating topical

information exchange, often on a voluntary basis. An

example is the cybersecurity domain and its

continuous information exchange which benefits all

the participants. However, such specialisation can

also create information silos and coordination

challenges when cross-domain incidents occur.

Some organisations were mentioned frequently in

the research data as key nodes for knowledge transfer.

The government situation center, Security committee,

National emergency supply agency, and Cyber

security center function as knowledge brokers,

following Davenport and Prusak (1998). Knowledge

brokers facilitate the exchange of both research-based

and tacit knowledge at the individual, organisational,

and systemic levels (Ward et al. 2009). The activities

of these knowledge brokers are based, but also limited

to legislation, and thus not ecosystem wide.

4.2 Interaction

Interaction and knowledge transfer between

organisations require a balance of people, technology,

and processes, as often categorised in knowledge

management theory (Chan, 2017). The research

findings are presented accordingly.

The human factor is critical to knowledge transfer

and development. Trust-based personal contacts were

found to substantially enhance knowledge flow,

facilitating deeper knowledge transfer and agility

among organisations. “I just called the guy I know”

as was mentioned in the interviews. Personal contact

from leadership or active experts is often required to

establish an initial connection between organisations.

Human interaction facilitates sharing of tacit

knowledge, which is not possible through other

means. In practice, a representative of a security

authority often provides insight or advice on

comprehensive security matters. These findings

resonate with prior literature. Informal ties often

Knowledge Management in Finnish Comprehensive Security Ecosystem

373

compensate for the limitations of formal coordination

mechanisms (Granovetter, 1985), and trust is a crucial

factor (Csepregi & Papp-Horváth, 2024). In the

context of comprehensive security Valtonen (2010)

suggests that trust, professionalism, and commitment

are fundamental enablers of successful inter-

organisational cooperation and knowledge transfer at

every level, and common security concerns are

emphasised over competitive dynamics.

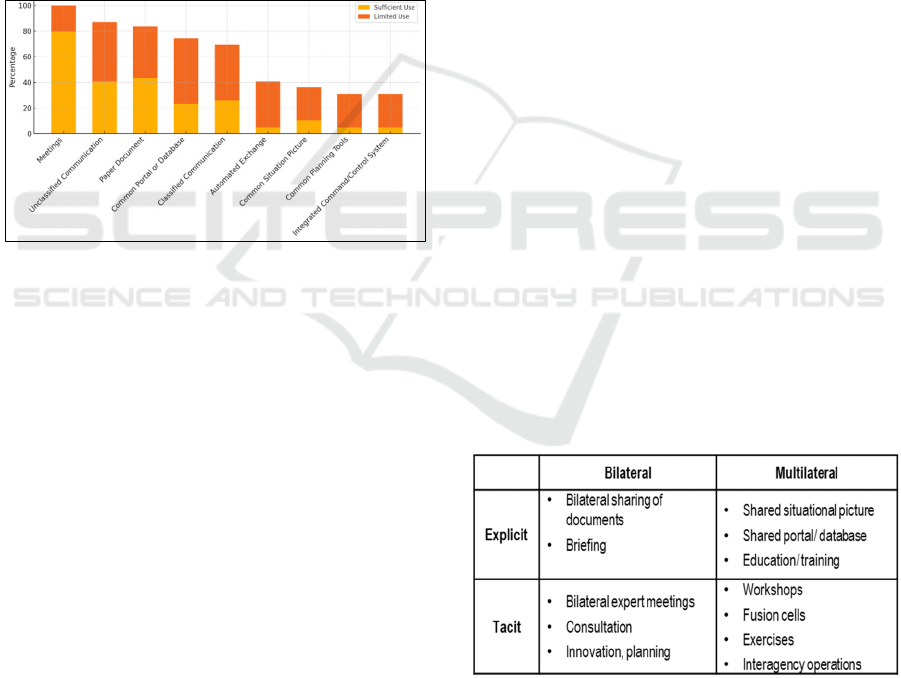

A technology factor, as data reveals, enables, but

in many cases, also limits, knowledge flows between

organisations. The usability of different means of

communication varied significantly between

organisations. The following chart (Figure 2) depicts

the survey responses concerning the availability of

different methods for information exchange, scaled as

sufficiently available, limited, or unavailable.

Figure 2: Availability of Information Exchange Methods (n

=39).

The data reveal several key findings. Traditional

methods dominate, as face-to-face meetings and

unclassified communication methods remain the

primary means for exchanging security-related

knowledge. These methods are easy to use and

available everybody. Security considerations also

influence method selection. In addition to face-to-

face meetings, secure networks and paper documents

play a significant role for security authorities who

often prioritise confidentiality over usability. While

basic digital communication is common, integrated

systems such as joint situation awareness applications

or collaborative planning tools show limited

adoption. Automated inter-organisational data

transfers are also rare. Technology primarily

facilitates knowledge transfer, leaving collaboration

as an option for future development.

Technological connectivity was found to mirror

the structure of comprehensive security knowledge

network. Security authorities have their own

classified networks, administration uses limited

restricted networks, and some domain-specific

portals are operated on the Internet. There is no

overlap between these networks, while a large

majority of organisations do not have access to any of

these networks. Limited technological integration is

evident even though there are some well-functioning

elements. The technological gap severely limits

knowledge flows between the entities, while the

majority of organisations have access only to open-

source information.

Processes facilitating inter-organisational

knowledge transfer were noticed to occur bilaterally

and multilaterally, each with distinct advantages and

disadvantages. Bilateral exchanges are prone to

deeper interactions when multilateral knowledge

transfers provide access to wider knowledge and save

time. Most organisations seemed to prioritise bilateral

exchange, since they are easier to organise, typically

more confidential, and involve more trust. Only 21%

of the private companies engage in multilateral

knowledge sharing, while security authorities (100%)

and administration (86%) were regularly involved in

multilateral exchanges. These organisations

consistently conduct also bilateral exchanges.

Explicit knowledge is easier to transfer and,

accordingly, is most commonly shared. Explicit

knowledge is often insufficient, because security-

related information often requires interpretation by

experienced experts. Additionally, organisational

learning requires interplay between explicit and tacit

knowledge, referring to Nonaka´s SECI model

(1994). In sum, inter-organisational knowledge

transfer processes include bilateral and multilateral,

as well as explicit and tacit knowledge transfer

between organisations. The most common processes

observed in the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Knowledge transfer processes. Modified based on

(Alavi&Leidner, 2001, p. 117).

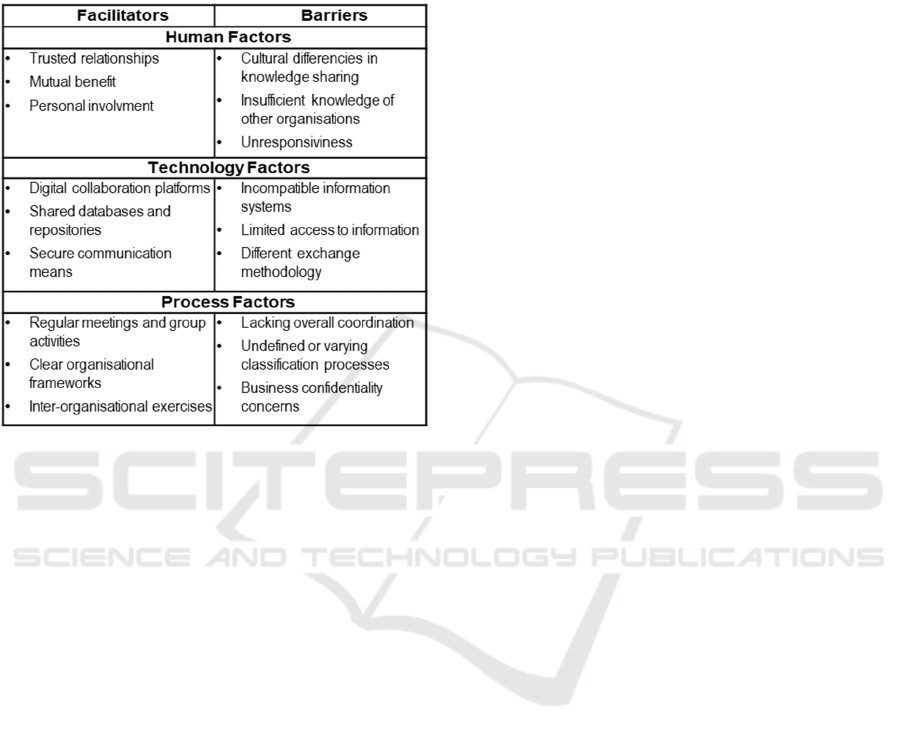

4.3 Facilitators and Barriers

Knowledge management theories suggest that certain

factors can either enhance or cause friction in inter-

organisational knowledge exchange (Nunamaker et

al. 2001; Fang et al., 2013). The survey revealed

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

374

similar findings. The three most frequent human-,

technology-, and process-related factors are listed in

Table 3.

Table 3: Facilitators and barriers to inter-organisational

knowledge transfer.

4.4 Knowledge to Be Managed

Knowledge is valuable only when it is relevant and

timely for the receiving organisation. It also needs to

add value to the knowledge that an organisation

already possesses. According to the findings,

knowledge requirements vary among organisations.

Moreover, knowledge in security contexts is not

static, but fluctuates based on organisational priorities

and situational demands. The challenge seems to be

to identify relevant information from the vast

amounts of incomplete and unreliable data. Hardly

any organisation indicated that the knowledge they

receive fully meets their requirements. This

underlines the importance of organisational

multisource knowledge management and absorptive

capabilities (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

Transferred knowledge in the security context

typically includes situational updates, incident

reports, and threat assessments. Knowledge of

protection and resilience is also valuable. Besides

topicality, other important attributes of knowledge

seemed to be the classification level, explisit/tacit

knowledge, and maturity in relation to the DIKW-

pyramid. The results indicate that the most common

transfer is unclassified but sensitive explicit

knowledge, often a written report. Examples of more

sophisticated transfers include the delivery of

authentic fingerprint data related to cyber threats or

secret raw data pertaining to intelligence findings

accompanied by expert interpretation. A higher

sensitivity of knowledge usually requires a habitual

relationship and trust between the organisations

involved. Understanding these attributes is important

for developing systematic knowledge management

arrangements.

5 DISCUSSION

Inter-organisational knowledge sharing is

fundamental to ensuring situational awareness and

operational continuity. This study has explored

knowledge management within Finland's

comprehensive security ecosystem. While the results

reflect subjective perspectives from representatives

of diverse organisations and may not fully capture the

continuously evolving security landscape, they

nonetheless enable the identification of key elements

for enhancing knowledge management efficiency

across a comprehensive security network. The

established theory-based 4-layer model on inter-

organisational knowledge management can capture

the phenomena and main research findings as a

framework, enabling a more comprehensive analysis

of knowledge-sharing practices.

The depth of knowledge transferred between

organisations varies significantly. While security

organisations have accurate and sensitive information

and dynamic interactions, many organisations remain

excluded from systematic security information

sharing. Non-governmental organisations may be

forced to rely on openly available information, which

is often unsystematic. Moreover, the lack of

standardised processes or dedicated personnel to

facilitate network-wide knowledge transfer is

problematic. Consequently, situational awareness

may remain superficial across networks. This

presents a significant challenge for wide and

heterogeneous knowledge networks. Rather than

attempting to maintain uniform high-quality

functioning across the network, it has been pragmatic

to prioritise inter-organisational knowledge

management among critical entities. It is important to

consider that practically any organisation may also

pose societal vulnerability and should be included in

more systematic knowledge sharing.

The Finnish comprehensive security model

operates through a decentralised structure in which

knowledge management responsibilities are

distributed across the network within their respective

domains, rather than hierarchically coordinated by a

Knowledge Management in Finnish Comprehensive Security Ecosystem

375

single entity. The findings indicate that besides

statuory requirements, mutual benefits motivate key

organisations to participate in knowledge-sharing

activities. Although self-synchronisation offers an

alternative approach, it remains limited due to

organisations’ lack of security expertise and access to

sensitive information. Informal links compensate for

formal limitations, as Granovetter (1985) noted. The

importance of active individuals and social networks

was still unexpected. The research findings suggest

that there may be a requirement for appointing

governmental knowledge broker to enhance network-

wide effectiveness by coordinating security

knowledge management and assisting preparedness.

Two main topics for future research have

emerged. First, expanding investigations into the

intenational context and second, a possible paradigm

shift towards Mass Collaborative Knowledge

Management (MCKM) (Borjigen, 2015) that values

knowledge from professional amateurs rather than

solely from exclusive organisations. An example is

provided by voluntary networks of open-source

analysts developing detailed documentation of the

Ukrainian war. Given the diversity of security

knowledge networks, knowledge-sharing challenges,

information proliferation, and AI advancements,

crowdsourcing security knowledge is a conceptual

alternative that is worth studying.

6 CONCLUSION

For an effective comprehensive security knowledge

network, alignment is required across all levels of the

proposed four-layer architecture: a common

conceptual framework, functioning network

structure, established knowledge transfer methods,

and effective delivery of actionable knowledge to

appropriate recipients in suitable formats and in a

timely manner. In addition, organisations need

knowledge absorption and utilisation competency to

identify and conduct necessary activities. According

to the research findings, all of these elements exist

within the current Finnish comprehensive security

ecosystem, but none operate at optimal levels,

indicating substantial room for improvement.

Network coverage, secure electronic communication

methods, and systematic inter-organisational expert

collaboration are the most important areas in need of

improvement. It is also worth mentioning that pre-

established cooperative networks and information

management protocols enable dynamic knowledge

transfer and collaboration during crises.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study has received partial financial support from

the Fund of Nils Eduard von Veh.

REFERENCES

Ackoff, R. L. (1999). Ackoff’s best: His classic writings on

management. Wiley. New York. http://archive.org/

details/ackoffsbesthiscl00russ

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Review: Knowledge

Management and Knowledge Management Systems:

Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues. MIS

Quarterly,25(1),107–136. https://doi.org/10.2307/

3250961

Andreeva, T., & Kianto, A. (2012). Does knowledge

management really matter? Linking knowledge

management practices, competitiveness and economic

performance. Journal of Knowledge Management,

16(4),617–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/

13673271211246185

Borjigen, C. (2015). Mass collaborative knowledge

management: Towards the next generation of

knowledge management studies. Program, 49(3), 325–

342. https://doi.org/10.1108/PROG-02-2015-0023

Chan, I. (2017). Knowledge Management Hybrid Strategy

with People, Technology and Process Pillars.

Knowledge Management Strategies and Applications.

IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.70072

Cobben, D., Ooms, W., Roijakkers, N., & Radziwon, A.

(2022). Ecosystem types: A systematic review on

boundaries and goals. Journal of Business Research,

142,138–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.jbusres.2021.12.046

Cohen, M., & Levinthal, W. (1990, March). Absorptive

Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and

Innovation. //classic_papers/absorptive-capacity.html

Csepregi, A., & Papp-Horváth, V. (2024). Overview of

Knowledge Sharing Concept in a Project Environment:

A Systematic Literature Review.

https://papers.academic-conferences.org/index.php/

eckm/article/view/2437/2260

Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working

Knowledge: How Organizations Manage what They

Know. Harvard Business Press.

Fang, S.-C., Yang, C.-W., & Hsu, W.-Y. (2013). Inter-

organizational knowledge transfer: The perspective of

knowledge governance. Journal of Knowledge

Management,17(6),943–957. https://doi.org/10.1108/

JKM-04-2013-0138

Galeotti, M. (2019). Russian Political War: Moving Beyond

the Hybrid. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/

9780429443442

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic Action and Social

Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness | American

Journal of Sociology: Vol 91, No 3. https://

www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/228311

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

376

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches

to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health

Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1049732305276687

Huxham, C. (2003). Theorizing collaboration practice.

Public Management Review, 5(3), 401–423. https://

doi.org/10.1080/1471903032000146964

Kebede, G. (2010). Knowledge management: An

information science perspective. International Journal

of Information Management, 30(5), 416–424. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2010.02.004

Loebbecke, C., van Fenema, P. C., & Powell, P. (2016).

Managing inter-organizational knowledge sharing. The

Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 25(1), 4–14.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2015.12.002

National Emergency Supply Agency. Topical questions

and answers concerning critical infrastructure and

preparedness. Retrieved 21 April 2025, from https://

www.huoltovarmuuskeskus.fi/en/a/topical-questions-

and-answers-concerning-critical-infrastructure-and-

preparedness

Nicolas, R. (2004). Knowledge management impacts on

decision making process. Journal of Knowledge

Management,8(1),20–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/

13673270410523880

Nonaka, I. (1994). A Dynamic Theory of Organizational

Knowledge Creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–

37. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

Nonaka, I., & Toyama, R. (2003). The knowledge-creating

theory revisited: Knowledge creation as a synthesizing

process. Knowledge Management Research & Practice,

1(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/

palgrave.kmrp.8500001

Nunamaker, J. F., Romano, N. C., & Briggs, R. O. (2001).

A framework for collaboration and knowledge

management. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences, 12 pp.-.

https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2001.926241

Phelps, C., Heidl, R., & Wadhwa, A. (2012). Knowledge,

Networks, and Knowledge Networks: A Review and

Research Agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4),

1115–1166. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0149206311432640

Plano Clark, V. L. (2019). Meaningful integration within

mixed methods studies: Identifying why, what, when,

and how. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 57,

106–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.cedpsych.2019.01.007

Polanyi, M. (1958). Personal Knowledge. Routledge.

Premkumar, G., Ramamurthy, K., & Saunders, C. (2005).

Information Processing View of Organizations: An

Exploratory Examination of Fit in the Context of

Interorganizational Relationships. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 22(1), 257–294.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045841

Rousseau, D. M. (2006). Is there Such a thing as “Evidence-

Based Management”? Academy of Management

Review,31(2),256–269. https://doi.org/10.5465/

amr.2006.20208679

Security Commitee. (2025). Security Strategy of Society

https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/16602

4

Tuomi, I. (1999). Data is more than knowledge:

Implications of the reversed knowledge hierarchy for

knowledge management and organizational memory.

Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Hawaii International

Conference on Systems Sciences. 1999. https://doi.org/

10.1109/HICSS.1999.772795

Valtonen, V. (2010). Turvallisuustoimijoiden Yhteistyö

Operatiivis-Taktisesta Näkökulmasta. National

Defence University. https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/

handle/10024/74154/Valtonen+-

+Turvallisuustoimijoiden+yhteistyo.pdf

van der Borgh, M., Cloodt, M., & Romme, A. G. L. (2012).

Value creation by knowledge-based ecosystems:

Evidence from a field study. R&D Management, 42(2),

150–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-

9310.2011.00673.x

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S., & Sullivan, Y. (2016).

Guidelines for Conducting Mixed-methods Research:

An Extension and Illustration. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 17(7). https://

doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00433

Vesterinen. (2022). Yrityksiin kohdistuva

hybridivaikuttaminen lisääntynyt.

Keskuskauppakamari. https://kauppakamari.fi/tiedote/

keskuskauppakamarin-selvitys-yrityksiin-kohdistuva-

hybridivaikuttaminen-lisaantynyt-sahkonjakelun-

keskeytyminen-yrityksille-suurin-uhka/

Vodă, A. I., BORTOÅž, S., & ÅžOITU, D. T. (2023).

Knowledge Ecosystem: A Sustainable Theoretical

Approach. European Journal of Sustainable

Development, 12(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/

10.14207/ejsd.2023.v12n2p47

Ward, V., House, A., & Hamer, S. (2009). Knowledge

brokering: The missing link in the evidence to action

chain? Evidence & Policy, 5(3), 267–279. https://

doi.org/10.1332/174426409X463811

Yan, G. (2020). The impact of Artificial Intelligence on

hybrid warfare. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 31(4),

898–917. https://doi.org/10.1080/

09592318.2019.1682908

Öberg, C., & Lundberg, H. (2022). Mechanisms of

knowledge development in a knowledge ecosystem.

Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(11), 293–307.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2021-0814

Knowledge Management in Finnish Comprehensive Security Ecosystem

377