Developers’ Insight on Manifest v3 Privacy and Security Webextensions

Libor Pol

ˇ

c

´

ak

1 a

, Giorgio Maone

2

, Michael McMahon

3

and Martin Bedn

´

a

ˇ

r

1

1

Brno University of Technology, Faculty of Information Technology, Bo

ˇ

zet

ˇ

echova 2, 612 66 Brno, Czech Republic

2

Hackademix, via Mario Rapisardi 53, 90144 Palermo, Italy

3

Free Software Foundation, 31 Milk Street, 960789 Boston, MA 02196, U.S.A.

fi

Keywords:

Webextensions, Manifest v3, Privacy, Security, Web Browsers, Survey Among Developers.

Abstract:

Webextensions can improve web browser privacy, security, and user experience. The APIs offered by the

browser to webextensions affect possible functionality. Currently, Chrome transitions to a modified set of

APIs called Manifest v3. This paper studies the challenges and opportunities of Manifest v3 with an in-

depth structured qualitative research. Even though some projects observed positive effects, a majority express

concerns over limited benefits to users, removal of crucial APIs, or the need to find workarounds. Our findings

indicate that the transition affects different types of webextensions differently; some can migrate without

losing functionality, while others remove functionality or decline to update. The respondents identified several

critical missing APIs, including reliable APIs to inject content scripts, APIs for storing confidential content,

and others.

1 INTRODUCTION

Webextensions are a collection of JavaScript code run

by a web browser. As web and browsers evolve, re-

quirements change, and occasionally, extension de-

velopers need to adapt their code (Teller, 2020).

At the end of 2018, Google proposed a break-

ing change in the webextension API called Manifest

v3 (Mv3) that changes several crucial mechanisms

of webextensions (Google Inc., 2018). The goal of

Mv3 is to enable the easy creation of secure, perfor-

mant, and privacy-respecting extensions, while writ-

ing an insecure, non-performant, or privacy-leaking

extension should be difficult (Google Inc., 2018). Ac-

cording to Google, Mv3 webextensions should have

the same capabilities as Manifest v2 (Mv2) webexten-

sions

1

. However, the proposal quickly received criti-

cism (O’Flaherty, 2019; Chrome-stats.com, 2025).

We started this research to shed light on the dis-

pute between Google and the critics. Specifically, we

aimed at answering research questions: (RQ1) How

are webextension projects affected by the migration

from Mv2 to Mv3? (RQ2) Are developers reluctant or

hesitant to migrate? (RQ3) Is the migration smooth?

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9177-3073

1

https://groups.google.com/a/chromium.org/

g/chromium-extensions/c/qFNF3KqNd2E/m/

uZlWrml1BQAJ

(RQ4) Does Mv3 make webextensions better? To find

answers to these questions, we conducted a structured

qualitative study complemented with a longitudinal

study based on chrome-stats.com presented in this pa-

per.

Due to the diversity of webextensions and the

distinct impact of Mv3 on various APIs offered

to webextensions, we observe miscellaneous conse-

quences. Some webextensions could have been up-

dated quickly. Other projects report a migration pe-

riod of up to one year. Some projects decided not

to migrate as Mv3 lacks essential APIs, or due to

frustration from frequent forced changes or changing

deadlines. Other projects remove functionality due to

missing APIs. Most participants do not consider Mv3

to make writing safe and privacy-friendly webexten-

sions easier, as participants need to spend time to find

workarounds around missing or buggy APIs.

We disclosed all research details to our partici-

pants. We stressed that participation in the research

is voluntary. Consequently, approval from a research

ethics board is not required.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2

describes differences between Mv2 and Mv3. Sec-

tion 3 reviews related work. Section 4 introduces our

methodology and the participants. Section 5 reports

the results and discusses their impact. The paper is

concluded by section 6.

Pol

ˇ

cák, L., Maone, G., McMahon, M. and Bedná

ˇ

r, M.

Developers’ Insight on Manifest v3 Privacy and Security Webextensions.

DOI: 10.5220/0013669000003985

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2025), pages 15-26

ISBN: 978-989-758-772-6; ISSN: 2184-3252

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

15

2 Mv2 AND Mv3 DIFFERENCES

Webextensions contain a file manifest.json with

metadata about the webextension, such as its name

or required permissions.

Browser vendors version the Manifest to adapt to

the evolving needs. Consequently, the browser can

run a webextension differently based on the Mani-

fest version. Mv3 builds on the previously used Mv2

and maintains most APIs available to webextensions.

However, some APIs and mechanisms available to

webextensions were redesigned.

Webextensions often need to maintain data. For

example, a user can configure and fine-tune the func-

tionality of many webextensions, or webextensions

need to store computed information about visited

pages or the browser as a whole

2

. Both Mv2 and Mv3

allow storing state in a database in the browser. How-

ever, the space is limited

3

. Consequently, Mv2 web-

extensions stored state in background pages, which

offered a private JavaScript run time environment

spanning the whole browser session in which the web-

extension can perform any computation or store any

data (Google Inc., 2018). Mv3 replaced the compo-

nent with background service workers that can stop

running and respawn at any time. The motivation is

to lower memory requirements as the memory is freed

when the worker stops running. However, the shift

from a persistent to the short-lived environment may

affect the capabilities of webextensions

4

.

Webextensions can observe web requests made by

the browser. Blocking web requests allow webexten-

sions to read and modify the content of the requests

and the responses. Various blockers have used this

functionality to block some requests completely or to

sanitize the replies. Non-blocking web requests al-

low only reading the messages. Mv3 removed block-

ing web requests and replaced them with declarative

net request API

5

. Declarative net requests allow web-

extensions to specify rules in advance that (1) de-

fine web requests that should be modified (for ex-

ample, by selecting specific domains or by applying

regexes on URLs), and (2) define actions on the se-

lected requests like blocking, redirecting, or modify-

ing the message. Nevertheless, blocking web requests

API is more powerful as the webextension could have

2

For example, the number of blocked trackers on the

currently visited page.

3

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Mozilla/

Add-ons/WebExtensions/API/storage/session

4

https://groups.google.com/a/chromium.org/g/

chromium-extensions/c/Qpr-Wf8BcsI/m/hC0RNrvqCwAJ

5

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Mozilla/

Add-ons/WebExtensions/API/declarativeNetRequest

used any data in the observed messages and exten-

sion state to decide the actions applied to the mes-

sage. For declarative web requests, the computa-

tion needs to happen in advance, lacking data current

to the exchanged message and webextension internal

state (Miagkov et al., 2019). In addition, the number

of declarative rules is limited.

3 RELATED WORK

Whereas some online resources already provide feed-

back from developers of webextensions (Barnett,

2021; Chrome-stats.com, 2025), this paper is the first

to systematically study the attitude of the developers

and the obstacles associated with the migration, like

the quality of documentation, ease of development,

and the maturity of the APIs, as well as the longitudi-

nal trends in the migration.

Pantelaios and Kapravelos (2024) study the effect

of Mv3; however, they do not learn first-hand experi-

ence from the developers and do not focus on privacy-

and security-related webextensions. They see 87.8 %

removal of APIs related to malicious behavior in

Mv3. However, after adaptation, 56 % of the exam-

ined malicious webextensions retain their malicious

capabilities within the Mv3 framework. Whereas they

found that Google refines the APIs to address devel-

opers’ concerns, we show that these refinements are

insufficient and a significant portion of webextensions

do not migrate. Our research participants often ex-

plain that missing APIs are the reason not to migrate.

Smith and Guzik (2022) also performed a qual-

itative analysis of developers’ attitudes to develop-

ing privacy webextensions. However, they focused

on the motivation of the developers to create privacy-

related webextensions and did not study the migration

to Mv3.

We are not the first to use chrome-stats.com data

for a long-term analysis. Hsu et al. (2024) provides

a holistic view of the webextensions listed in Chrome

Web Store and their lifecycle. The work of Sheryl

Hsu et al. is more generic than this paper. Neverthe-

less, they do not deeply study and explain the issues

of the Mv3 transition. Moreover, their paper was writ-

ten before Google released the first Chrome that turns

off Mv2 webextensions by default. We are the first to

show the effect of the deadline.

We observe uncertainties about the effectiveness

of the APIs (see, for example, section 5.5.3). While

previous studies (Schaub et al., 2016) unveiled that

some users feel protected by webextensions, we show

that developers of webextensions are not certain about

the correct behavior of their webextensions.

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

16

Without a doubt, webextensions are misused for

malicious purposes (Chen and Kapravelos, 2018; Fass

et al., 2021) For example, Chen and Kapravelos

(2018) discovered thousands of webextensions poten-

tially leaking privacy-sensitive information, some of

which have over 60 million users. Fass et al. (2021)

detected suspicious data flows between external ac-

tors and sensitive APIs in webextensions and demon-

strated exploitability for 184 extensions.

These security problems led to a debate about

removing some capabilities for extensions, with the

most dangerous capability being the ability to inspect

and modify or prevent any request the browser makes

to any website (Borgolte and Feamster, 2020). Re-

moving the functionality would clearly prevent mali-

cious extensions from misusing it, and, hence, protect

users’ privacy (Borgolte and Feamster, 2020). The re-

moval of the blocking web request API goes in this di-

rection. However, previous work has pointed out that

removing blocking web request APIs does not prevent

malicious webextensions from observing all browser

traffic (Miagkov et al., 2019).

Borgolte and Feamster (2020) benchmarked

eight popular privacy-focused browser webexten-

sions. They measured that privacy-focused extensions

not only improve users’ privacy but can also increase

users’ browsing experience.

Previous work also showed that the declarative net

request API is inferior to the blocking web request

API, as webextensions cannot make decisions based

on contextual data (Miagkov et al., 2019).

Some webextensions unintentionally and unnec-

essarily hinder security. For example, Agarwal

(2022) detected extensions that remove security head-

ers or affect pages on top of their declared pol-

icy. Such modifications continue to be applicable in

Mv3 (Agarwal, 2022).

4 THE STUDY

To address the research questions, we performed a

structured qualitative research based on a question-

naire with open questions sent to webextension de-

velopers. We also observed Chrome Web Store

and tracked published versions. For missing data,

we employed Chrome-Stats, an independent project

that tracks published webextensions in Chrome Web

Store.

4.1 Methodology

Our research goal needs to focus on the first-hand ex-

perience to get insight into the mindset of developers

of distinct web extensions. As we did not know what

properties might influence the migration, the obsta-

cles to migration, and the qualities that Mv3 brings to

the webextension ecosystem, we opted for qualitative

research with open questions to allow the respondents

to express their views freely. To save time for devel-

opers and give them enough time to contribute, we

prepared a structured questionnaire

6

and asked parti-

cipants to reply in one month, but allowed them to ex-

tend the deadline. Several projects asked for a dead-

line extension.

One of the authors of the paper keyworded all

replies to a vocabulary based on the content of the

open answers. Another author checked the key-

worded answers. During the process, when we had

access to an independent source, we also checked the

validity of the answers (for example, we compared the

migration status to the published version in Chrome

Web Store). We ignored some answers, for example,

when respondents speculated or did not provide a per-

sonal experience for questions where we sought per-

sonal experience.

4.2 Search for Participants

We selected privacy- and security-related projects

based on publicly listed webextensions for Firefox

7

and Chrome

8

. We asked 3,041 projects and 10 ad-

ditional WebExtensions W3C working group partici-

pants questions aiming to answer our research ques-

tions in November 2023. We received the latest reply

at the beginning of February 2024.

For Firefox, we studied webextensions listed un-

der the Privacy and Security category

9

. Hence, we

contacted only developers who self-reported that their

webextensions deal with privacy or security. As the

listings do not provide contact details to reach devel-

opers, we collected e-mail addresses for support. We

gathered e-mail addresses for 2,159 webextensions

listed at addons.mozilla.org. 1,547 webextensions do

not contain a support link in the listing, and we omit-

ted these webextensions from our research.

At the time we started our research, Chrome Web

Store

10

did not offer a category for privacy or security

webextensions. However, a visitor to the store can

search for keywords. We searched for privacy and se-

curity, and collected webextensions that the store of-

fered. We expanded the list as long as the names of

the webextensions were connected to privacy or secu-

6

https://pastebin.com/nTFykFNi

7

https://addons.mozilla.org

8

https://chrome.google.com/webstore/

9

https://addons.mozilla.org

10

https://chrome.google.com/webstore/

Developers’ Insight on Manifest v3 Privacy and Security Webextensions

17

rity. Although we have not curated the list (so it also

contains webextensions that do not deal with privacy

or security), we validated the purpose of the webex-

tensions by one of the questions (see Table 2). Only

two participants develop webextensions not related to

privacy and security. We collected 1,110 webexten-

sions from Chrome Web Store and found 1,058 e-mail

addresses.

Additionally, we asked regular WebExtensions

W3C Working Group participants, as the group

comprises active webextension developers and other

stakeholders. They have first-hand experience in the

standardization process and should be the most famil-

iar with the issues and opportunities raised by Mv3.

In total, we found 2,702 unique e-mail addresses

in addons.mozilla.org and Chrome Web Store. 12 of

these addresses belonged to the projects of the Web-

Extensions W3C Working Group participants, and

we excluded these addresses. Hence, we collected

2,690 e-mail addresses from addons.mozilla.org and

the Chrome Web Store, which we used for the inter-

views.

4.3 Participants

We received 33 replies that contained meaningful an-

swers. One of the participants provided answers for

six projects in one answer without sufficient data to

distinguish between the projects. One participant re-

ported two very similar project names in one answer.

We counted each of these two participants just once.

One participant answered for two projects and another

for three projects. As the answers clearly distinguish

between the projects, we counted each answer as one

for questions dealing with developers’ opinions and

counted each project separately for questions dealing

with the projects.

We gave each reply a unique participant project ID

(PPID) of RXX where XX are two digits. We refer to

PPID in the following text to distinguish the projects

or their answers.

Table 1 shows that we received answers for both

small webextensions that have just a few users, as well

as answers for webextensions with hundreds of thou-

sands of users or more

11

. Consequently, we provide

insight into both small and large projects.

11

Previous research reports that the number of users re-

ported by Chrome Web Store is not precise (Hsu et al.,

2024) as users not using their computer longer than a week

are not counted. Additionally, users with more browser pro-

files might be counted multiple times. We explicitly asked

the participants to provide their estimates. However, of-

ten, participants did not have more precise numbers than

Chrome Web Store.

Table 1: Number of users of the participating extensions.

Users Participating webextensions

Undisclosed 5

Few 1

Tens 3

Hundreds 9

Thousands 3

Tens thousand 5

Hundreds thousand 3

Millions 1

The participants develop various kinds of webex-

tensions (see Table 2). We decoded the primary pur-

pose of each webextension in all answers except for

the participant R25. R25 is both an ad blocker and

a data obfuscation tool, and is counted in both cate-

gories.

Table 2: The purpose of participating webextensions.

Purpose Count

Cookie banner removal 2

Page content sanitizer 1

Cookie manager 3

Ad blocker 3

Tracker blocker 1

Other blocker 3

Referer modifications 1

Password manager 2

Authentication tool 1

Checksum validator 1

Message encryptor 1

Data obfuscation 1

Proxy manager 2

Network boundaries separation 1

Security leak detector 1

Video meeting selector 2

Not related to privacy or security 2

Undisclosed 3

14 webextensions attract any user. 3 webexten-

sions are suitable for users of a specific site, 2 webex-

tensions appeal to customers of a specific company. 4

webextensions aim at power users who usually have

certain IT skills and 1 webextension is for testers.

R22 is both a webextension for power users and a

webextension for everybody. 7 projects did not dis-

close the type of a user attracted by the webextension.

The majority of webextensions support

Chromium-based browsers (at least Chrome re-

ported), and 3 of these also support at least one

Safari-based browser. While 6 projects support

only Firefox, we did not receive any answer of

a developer that supports just Chromium-based

browsers. Nevertheless, 1 project reported that it

would remove Firefox support during the migration

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

18

to Mv3. Another project added support for Firefox

during the migration to Mv3.

We ignored replies that were not in English. All

look like a confirmation e-mail or are too short to con-

tain answers to the questions. We also ignored mes-

sages providing answers for projects not developed by

the respondent. We ignored one reply of a webexten-

sion developer that plans to retire the webextension as

it is obsoleted by other webextensions. The developer

did not have any practical experience with Mv3 and

did not provide any relevant answers.

Often, we received a confirmation e-mail. We

were asked to confirm the message a few times by

clicking a link or sending another e-mail. In such

cases, we followed and performed such actions. How-

ever, we did not create accounts when we were asked.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This section provides an analysis of the responses in

the context of our research questions.

5.1 RQ1: Are Webextensions Affected?

Firstly, we were interested in whether our participants

are affected by the Manifest change and their migra-

tion plan (RQ1). Table 3 shows that the majority of

participating web extensions are affected. One project

reported both that it is inactive and unsure how af-

fected; that project is counted only as inactive.

Table 3: Migration status (at the end of 2023 or the start of

2024).

Affected by Mv3?

Not planned

Not started

Exploration

Paused

In progress

Finished

Yes 5 0 2 2 7 6

No 0 1 0 0 0 1

Likely not 0 1 0 0 0 0

Not sure how 1 1 0 1 0 0

Uses Mv3 from start 0 0 0 0 0 1

Project inactive 0 1 0 0 0 0

4 projects do not plan to migrate the Chrome ver-

sion of the extension and they want to continue the

extension only for Firefox. One project plans a com-

plete shutdown, and one is unsure if the author would

bother with the migration. 2 paused the migration

as there are missing APIs, whereas one project seems

confused about the scope of changes and frustrated

with the impact of the changes on the users. Whereas

6 projects declare a full transition to Mv3, 2 projects

plan to keep the code for Firefox in Mv2. For exam-

ple, one project reported compatibility issues.

The rest of this subsection considers only the 22

webextensions that self-reported to be affected, as

these projects reported meaningful answers to ques-

tions regarding features that were added, lost, or

needed to be rewritten due to the Manifest change.

19 projects did not report any new feature stem-

ming from Mv3. Only 2 projects reported that the

webextension gains availability on low-resource sys-

tems, and a single project reports that it became com-

patible with Android during the migration. Addi-

tionally, R07 reports that they reimplemented their

webextension to Mv3, and the new declarativeNetRe-

quests allowed the extension to interact with web re-

quests less compared to the web request API — con-

sequently, the extension improved performance.

Table 4 shows that almost half of the webexten-

sions do need a rewrite. Most often, the change in

handling background scripts triggers the need for a

rewrite. Only 2 projects declared that a major re-

design of the webextension is needed. One of the res-

pondents reported that he needed to push for a missing

API that browser vendors later added.

Table 4: What needs to be rewritten?

Response count

Undisclosed, probably nothing 13

Background scripts 6

Migration to declarative net requests 3

Initialization code 1

Communication to content scripts 1

Communication to pop-up window scripts 1

External library that is not migrated 1

Huge redesign 2

One respondent shared that they need persis-

tent background pages and found a workaround that

prevents the browser from stopping the background

pages. They found that the service worker runs for-

ever if they initiate a periodic request to local storage.

Nevertheless, this technique defeats the aim of remov-

ing background pages to share resources, especially in

limited environments like on phones.

Only 2 projects stated that they lost functionality

due to migration; in both cases, due to dependency on

the blocking web request API. However, 6 projects

decided not to migrate. Some additional projects did

not migrate in time, even though the projects antici-

pated migration in their answer.

5.2 RQ2: Obstacles in Migration

RQ2 focuses on why the projects are hesitant or even

reluctant to migrate.

Developers’ Insight on Manifest v3 Privacy and Security Webextensions

19

5.2.1 Lack of APIs

The most apparent reason complicating or even pre-

venting the migration is the lack of APIs. 3 projects

lack APIs simplifying work with non-persistent back-

ground workers, and 1 project considers the back-

ground service workers buggy. The lack of block-

ing web requests impacts 6 projects, including one

project that self-reported that it was still determining

the exact scope of the impact. One project reports that

permissions work differently in Firefox and Chrome.

2 projects consider that Mv3 APIs need more real-

world experience and are not mature enough.

Some developers actively highlight missing APIs

to browser vendors. For example, R07 was successful

and migrated after the vendors added a new API.

5.2.2 Stability and Maturity of APIs

Table 5 shows that the respondents disagreed on the

maturity and stability of the APIs. We attempted to

correlate the satisfaction with the APIs’ maturity and

stability to project purpose or migration status, but

found no correlation. Interestingly, similar projects

have varying opinions on this matter.

Table 5: Satisfaction with the maturity and stability of APIs.

Response count

Undisclosed 5

Not studied the APIs 8

No opinion 3

No 7

Yes, but problems with Firefox 1

Yes, but some use cases missing 1

Yes 4

Manifest v3 APIs are more polished 1

5.2.3 Quality of Documentation and Debuggers

Most participants who expressed their views on the

documentation quality were positive (13 projects)

rather than negative (3 projects). Yet, the participants

expressed that they lack more examples. Also, par-

ticipants expressed worries about whether the docu-

mentation is up-to-date due to changes in the APIs

and expressed uncertainty about the stability of the

APIs, as the documentation does not highlight APIs

that can change. Some projects expressed difficulties

in navigation and a lack of comprehensibility.

R01 gives an example of broken documentation

in oversimplifications. Developers are expected to

replace setTimeout calls with Alarms API

12

. How-

12

See https://developer.chrome.com/docs/extensions/

develop/migrate/to-service-workers for the advice.

ever, R01 found that it is more complex, and the de-

veloper must carefully decide the correct approach.

R07 is not sure how host permissions are supposed

to work. They are difficult to test, and they work dif-

ferently in different browsers. The documentation is

not clear. R07 also complains about documentation

for Safari.

Most participants did not express their views on

debugging tools. However, 5 projects find debug-

ging tools good. Some projects consider the debug-

ging tools difficult to use, for example, in the context

of debugging imported libraries.

5.2.4 Browser Compatibility

Another possible reason that might prevent projects

from migrating is code split. Only R35 reported that

the project used different code bases for Firefox and

Chrome, and the project plans to merge the code

bases during migration to Mv3. Additionally, R23

finished the migration, and while the project did not

support Firefox before the migration, it added the sup-

port during the migration. 2 projects plan to keep

the same code base for all supported browsers after

migration, and one project inserted browser-specific

workarounds into the code base during the migration.

Other projects are going in the negative direction:

6 projects started to use different code bases dur-

ing the migration, additional 6 projects do not plan

migration (meaning that the projects drop support for

Chrome), and 1 project dropped support for Firefox.

R34 warns that the uncertainties in deadlines and

support mean the project might need to migrate twice:

first, for Chrome, and later for Firefox. That means

that some decisions and development time might be

invested unnecessarily.

R19 postponed migration until it becomes un-

avoidable. Although the participant believes the ex-

tension should be compatible with Mv3, he is only

interested in migrating once Firefox forces him to do

so. R19 is prepared to lose all Chrome users. This de-

cision makes sense for Firefox users as it allows the

author to focus on other aspects of the extension that

directly impact them.

In summary, while we observe some benefits of

the transition on some projects, most projects sup-

port fewer browsers or increase maintenance costs by

introducing multiple code bases or browser-specific

workarounds.

In this regard, we asked if Mv3 improves the com-

patibility of webextensions across browser vendors.

One participant did not know that Mozilla works on

Mv3 support for Firefox. While counting this project,

14 projects expressed a negative opinion. R08 and

R19 highlight that Mv3, as implemented by Chrome,

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

20

removes some functionality still available in other

browsers, making the compatibility worse. Never-

theless, eight participants expressed positive answers.

One of these is R07, who expects positive improve-

ments in compatibility in the long run.

5.2.5 Confusion About Plans

Developers are uncertain about the plans. For exam-

ple, R33 lost trust in the deadlines and paused the mi-

gration. Only 5 projects are satisfied with the infor-

mation given by browser vendors whereas 8 projects

are not satisfied. One of these unsatisfied projects

does not understand the Firefox plan. Additional 4

projects do not understand the Chrome plan.

Our participants are also unsure about the motives

for the changes introduced by Mv3. Some, like R09

and R19, add that they do not understand why some

APIs must be removed. On the contrary, R14 ap-

proves access to the content of web requests as it gives

very high powers to webextension developers. How-

ever, Chrome does not remove access to the content

of the web requests, as that is also possible by not

blocking web requests (also stressed by R27). Even

so, R14 is correct in the sense that malicious actors

will have limited powers as they would not be able to

change the content of web requests and replies.

R19 speculates on motives behind the scenes. Ac-

cording to the developer of R19, the change to Mv3

benefits Google’s business model.

5.3 RQ3: Migration Process

RQ3 deals with the migration period — is it smooth

or takes much time?

Most projects that finished the migration by the

time they responded reported low impact on the code

and consequently invested only limited development

time in the migration: 3 projects invested just days

(up to a work-week), and one project needed a work

month. In contrast, R29 is an exception that reim-

plemented well in advance despite huge costs and

months of working time.

Similarly, projects estimating a long migration

time defer the migration.

• Two projects expected a short migration process

but had not invested any time in the migration be-

fore they answered our questionnaire.

• Two projects had already invested several days

and are expected to invest several more to com-

plete the transition.

• One project had already invested less than one

month and expected to finish in one more month.

• Six projects expected to need multiple months

for the complete transition (some did not disclose

their expectations, others mentioned four months

up to one year). These projects were in different

transition phases, often around the middle.

To shed more light on the migration process

without unnecessarily disturbing the developers, we

tracked the published version in the Chrome Web

Store around the migration deadlines (see Table 6). At

the beginning of June 2024, Google removed featured

badges from Mv2 webextensions. A featured badge is

manually given to projects that follow Google’s best

technical practices and meet a high standard of user

experience and design (Kim, 2022).

Almost all projects that advertised that they

were going to migrate managed to publish a Mv3-

compatible version of their extension. R10 expressed

that he got busy and could not finish the migration

in time. R27 and R33 expected a smooth transition

of just a few days, yet they did not update. A prob-

able reason is that R27 waits until Firefox supports

Mv3 properly, as expressed in the answer. R33 ex-

plained that they lost faith in the deadlines. Conse-

quently, more than ten thousand Chrome Web Store

users lost their webextensions. R01 migrated a short

time before the announced Featured badge deadline

and managed to keep the badge.

Let us focus on the internals that might complicate

the migration and how the participants deal with the

challenges arising from the change of the APIs.

5.3.1 Web Request API

14 participating webextensions use Web Request

API. However, 3 of them use the API just for non-

blocking purposes, so 11 participating extensions

need the blocking Web Request API. These partici-

pants approached the challenge of migration differ-

ently.

Two proxy managers, one page content sanitizer,

and one tracker blocker claim that the functionality

can be reimplemented using Mv3 APIs without func-

tionality loss. However, one of the proxy managers

explained that the implementation suffers from bugs.

Additionally, the project maintainer of the tracker

blocker explained that many blockers want to provide

feedback to users on what they did to each page. As

the declarative net request API does not provide feed-

back, they keep using Web Request API in parallel

to the declarative net request API and estimate what

actions should have happened through the declarative

net request APIs.

One blocker (R31) removed a feature depending

on the blocking Web Request API and, consequently,

lost functionality during the migration.

Developers’ Insight on Manifest v3 Privacy and Security Webextensions

21

Table 6: Status of the participating projects around the Chrome deadlines to make the transitions.

Participant

project ID

Expected

migration

duration

Before badge After badge Chrome 127 Chrome 127

deadline deadline early release stable release

2024-05-24 2024-06-04 2024-07-17 2024-07-23

Mv? Featured Mv? Featured Mv? Featured Mv? Featured

badge badge badge badge

R04 Not affected 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R13 Several hours 3 NO 3 NO 3 NO 3 NO

R23 Days 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R26 Days 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R27 Days 2 YES 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

R33 Days 2 YES 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

R07 1–2 months 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R03 Months 2 NO 3 NO 3 NO 3 NO

R10 Months 2 YES 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

R29 Months 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R01 12 months 2 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R34 Very long 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R18 Undisclosed 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R31 Undisclosed 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES 3 YES

R06 Not planned 2 YES 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

R14 Not planned 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

R16 Not planned 2 YES 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

R17 Not planned 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

R19 Not planned 2 YES 2 NO 2 NO 2 NO

An adblocker, an authentication tool, and two

cookie managers state that the migration is impossi-

ble. One project did not explain why it uses the block-

ing web request API; other 3 participating webexten-

sions need to modify the requests. The projects de-

cided that it is better not to offer the extension than to

offer an extension that does not fully work.

One project did not reveal its approach to the prob-

lem, and one project was still in the process of decid-

ing how to approach the issue.

It looks like the declarative net requests API is

suitable for some types of webextensions (proxy man-

agers, page content sanitizers, some blockers), but

other types of webextensions cannot use the API to

reimplement the original behavior (mainly various

blockers, cookie managers, and authentication tools).

This division likely stems from the different ways that

the webextensions have used the blocking web re-

quest API, for example, from the different number

and predictability of the rules.

5.3.2 Storing State

Another common problem is the state stored in back-

ground scripts. While Mv2 webextensions can use

background variables to store states, Mv3 webex-

tensions need the asynchronous APIs to access stor-

ages offered by browsers. Consequently, other scripts

might run while the browser performs the asyn-

chronous calls. The majority of participating web-

extensions (18) store state in background scripts.

8 projects answered that they do not store state.

Most projects find handling state challenging or

cannot make it work (see Table 7). Two projects keep

confidential information that should stay in RAM in

the browser storage. R28 underlines the issue of stor-

ing data on private tabs. However, the content of vari-

ables in background scripts of Mv2 webextensions

could have been moved to swap as well. So here,

the better solution should be to provide an API that

can safely store confidential content. Two projects

expressed that the storage is slow. One project de-

pends on an external library, so it needs to wait un-

til the library is migrated or rewrite the code. One

project worries that messages sent from other parts of

the extension do not start the worker.

Table 7: Is migration to background workers smooth?

Response Webext. count

Yes 1

General challenge 7

New solution does not work well 6

Undisclosed 6

Only 1 project feels impacted by the asyn-

chronous calls of the storage access. 2 more projects

expressed a small impact.

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

22

Table 8: Migration status of all projects we selected during

the search for participants (2024-08-26).

Version in store Count Percentage

Mv2 266 26.0 %

Mv3 756 74.0 %

Removed from store with Mv2 19 21.6 %

Removed from store with Mv3 69 78.4 %

5.4 Comparison to all Selected Projects

in Chrome Web Store

Recall that we found 1,110 webextensions of inter-

est in Chrome Web Store (see Section 4.2). Table 8

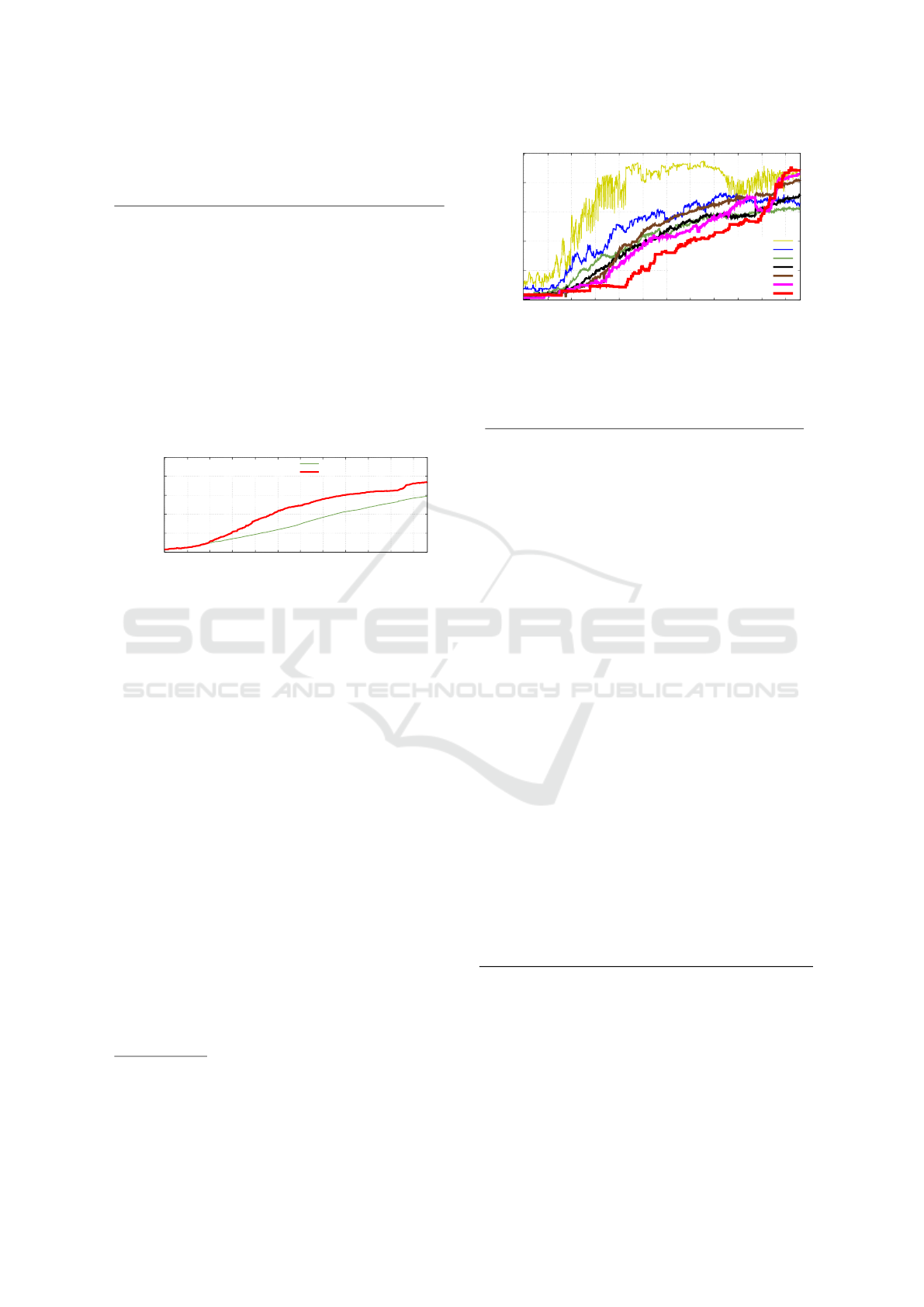

summarizes the status of the extensions at 2024-08-

26, and Fig. 1 shows the progress of migration in time

with the comparison to all extensions.

0

20

40

60

80

100

2021-10-01

2022-01-01

2022-04-01

2022-07-01

2022-10-01

2023-01-01

2023-04-01

2023-07-01

2023-10-01

2024-01-01

2024-04-01

2024-07-01

All extensions

Privacy and security extensions

Extensions migrated to Mv3 [%]

Figure 1: Share of webextensions that migrated to Mv3.

Figure 2 shows the migration status of the selected

privacy and security webextensions grouped by the

user count

13

over time. At the beginning of the time-

frame, small webextensions were more likely to em-

ploy Mv3. This trend is likely caused by new projects

starting directly in Mv3 and avoiding the transition.

Projects with bigger user count were more likely to

wait. This trend is especially visible for webexten-

sions with more than a million users. The transition

rate increased significantly in about three months be-

fore the transition deadline. 44 out of 50 projects with

more than a million users had migrated by the end of

August 2024. Nevertheless, six projects with a huge

user count did not migrate in time.

Our study represents a much higher share of

projects with troubles during migration (see Tab. 1)

compared to the overall picture. Even so, we con-

sider alarming that about one quarter of projects in

our research group did not migrate. The analysis of

responses to our questionnaire provides an explana-

tion for why projects decided not to migrate.

13

See footnote 11 and note that users with deacti-

vated webextensions, for example, because their browser

no longer supports Mv2 webextensions, are counted by

Chrome Web Store while their browser checks for updates.

0

20

40

60

80

100

2021-10-01

2022-01-01

2022-04-01

2022-07-01

2022-10-01

2023-01-01

2023-04-01

2023-07-01

2023-10-01

2024-01-01

2024-04-01

2024-07-01

Up to 10 users

1-100 users

101-1000 users

1001-10000 users

10001-100000 users

100001-1000000 users

More than million users

Extensions migrated to Mv3 [%]

Figure 2: Share of privacy and security webextensions (with

respect to their user count) that migrated to Mv3.

Table 9: Removal reason as listed by Chrome-stats.com.

Reason Mv2 Mv3

Bundled with unwanted software 0 2

Policy violations 3 7

Malware 2 19

Unknown 14 41

5.5 RQ4: Benefits of Mv3

The last research question deals with the possible ben-

efits of Mv3 to webextensions.

5.5.1 Is Mv3 Safer than Mv2?

Some of the projects in our group of likely privacy-

or security-related extensions were removed by July

2023 (see Tab. 8 and 9). The removal might have been

initiated by the owner of the webextension who de-

cided to stop offering the code. Often, the removal

is due to fraudulent purposes of the webextension.

As a significant portion of the removed webextension

for fraudulent behavior were published with Mv3, we

question if the goal of designing Mv3 as a safer re-

placement holds in practice.

5.5.2 Lack of Benefits to Users

A majority of our participants do not see a benefit for

the users in the migration to Mv3 (see Table 10).

Table 10: Will Manifest V3 make your extensions better for

your users?

Response Webext. count

Yes 2

Yes (only in Firefox for Android) 1

No 15

Uses Mv3 from start 1

Both participants who think that Mv3 will im-

prove their extension for users see the main benefit in

making their webextension less performance-heavy.

For example, R07 finds the new declarative net re-

Developers’ Insight on Manifest v3 Privacy and Security Webextensions

23

quest API less performance-heavy. R16 considers

Mv3 to have made webextensions more accessible to

users. R23 highlights the benefit of Mv3 in preserv-

ing the state of the extension among restarts of the

browser caused by the operating system.

Some of the projects that do not think that Mv3

will make their webextension better to their users fear

future changes. Two projects are aware that their Mv3

webextension is buggy. Some recall that some re-

moved APIs (like the blocking Web Requests API)

do not have a full replacement, meaning some exten-

sions cannot be fully migrated. R26 needed to remove

a feature as he did not understand how to implement

the functionality using Mv3 APIs.

R01 expressed: “The gist of Mv3 work is that it

is work that is almost entirely invisible to the user if

we do it right. The users will only notice that some-

thing changed if something no longer works right or

is missing. There are almost no benefits to users, and

certainly none that the vast majority will ever notice.

When we work on MV3, whether for Chrome or Fire-

fox, we are not working on making our webextension

work better for its users. We are running to stay in

place.” R29 adds that migration to Mv3 is the biggest

project they need to undertake, yet the migration is

completely opaque to users.

5.5.3 Content Scripts

Content scripts run in the context of a visited page

and have access to its document object model. Conse-

quently, they can manipulate the content of the page,

including removing, replacing, or extending some

parts of the visited page or the page as a whole.

Some webextensions need to inject content scripts

that must run before page scripts start running.

For example, such content scripts can change the

implementation of some APIs to provide modi-

fied or fabricated values (Michael Schwarz and

Gruss, 2018; Pol

ˇ

c

´

ak et al., 2023). Browsers offer

scripting.RegisteredContentScript API that

allows injecting content scripts to the page

14

. How-

ever, this API is not available for Mv2 webexten-

sions in Chrome

15

. Nevertheless, this API is not the

only way to inject content scripts. For example, some

projects like NoScript Commons Library solve the is-

sue of reliable injection for Mv2 webextensions using

other APIs (Pol

ˇ

c

´

ak et al., 2023).

Hence, we asked the participants if they needed to

run content scripts in advance and if they were con-

14

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/

Mozilla/Add-ons/WebExtensions/API/scripting/

RegisteredContentScript

15

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Mozilla/

Add-ons/WebExtensions/API/scripting

fident that their scripts would indeed run in time in

Mv2 and Mv3. Table 11 shows that only six partici-

pants replied; most were unsure if they inject scripts

on time in their Mv2 extension, and no one is sure in

the Mv3 version. This raises serious questions about

the reliability of the extensions. While the develop-

ers are not sure that the webextensions work as they

should, should users depend on such webextensions?

Do users understand the risks? We leave answering

these questions to future research.

Table 11: Are developers confident that content scripts run

on time? (- means undisclosed, ? means unsure).

PPID Mv2 Mv3 Purpose of content scripts

R01 - - Replace some DOM parts

and modify APIs available

to page scripts

R15 No ? Modify APIs available to

page scripts

R25 - - Replace some DOM parts

R28 Yes No Store settings

R31 No No Replace some DOM parts

R35 Yes No Replace some DOM parts

The developer of R16 and R17 further adds that

he is not confident that content scripts run in time, so

he gives up all efforts on extensions that need such

functionality. The lack of suitable APIs likely pre-

vents some extensions from being developed, as po-

tential developers are not persuaded that the exten-

sions would be reliable.

A related issue is that Firefox suffers from a long-

standing bug 1267027

16

that prevents content scripts

from injecting scripts by inserting script elements

to the page in the presence of Content Security Policy

that disallows such scripts. This means that the author

of the visited page can intentionally or unintention-

ally prevent webextensions from performing their in-

tended functionality if the author of the webextension

is unaware of the bug. For example, GitHub contains

tens of issues referring to the Firefox bug

17

.

Table 12 shows the replies of our respondents

who support Firefox. According to the responses of

the participants, the majority is not affected. How-

ever, only one participant disclosed the mitigations

employed by the webextension — the webextension

modifies the Content Security Policy. As the policy

is primarily intended to prevent bugs like cross-site

scripting, lowering the policy might expose users to

unintentional security risks (Agarwal, 2022).

16

https://bugzilla.mozilla.org/show bug.cgi?id=

1267027, the bug was opened 2016-04-23 and is not

fixed as of 2024-07-17.

17

https://github.com/search?q=https\%3A\%2F\

%2Fbugzilla.mozilla.org\%2Fshow bug.cgi\%3Fid\

%3D1267027&type=issues

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

24

Table 12: Webextensions affected by Firefox bug 1267027.

Response Webext. count

Affected 2

Undisclosed 3

Do not know 1

Not affected 9

We see two potential approaches to solve the prob-

lem. Firstly, Firefox should fix bug 1267027, so that

content scripts work predictably and compatibly with

Chromium-based browsers. Alternatively, browsers

should provide a configurable and reliable script in-

jection mechanism without side-effects

18

. The latter

approach is better as it does not leave artifacts that

can be misused for browser fingerprinting (Starov and

Nikiforakis, 2017; Gulyas et al., 2018).

5.5.4 APIs Missing in General

Finally, we asked participants about the APIs they

think are missing. These APIs can inspire browser

vendors to improve the browser’s extensibility and en-

able developers to create webextensions that are im-

possible today.

Some developers highlighted browser compatibil-

ity. For example, they mentioned that some APIs

behave differently in Firefox and Chromium-based

browsers or that Firefox has additional APIs like the

DNS API

19

or event pages

20

.

Other developers suggested improvements to ex-

isting APIs. For example, the web request API pro-

vides the browser tab ID, but it does not provide the

URL of that tab. Currently, webextensions need to de-

velop workarounds to obtain the URL. The extended

API could simplify the code of webextensions. An-

other example is to provide a dedicated API to change

web request headers. Some provided further exam-

ples of improvements to web requests, such as allow-

ing blocking based on resolved IP addresses and in-

formation from TLS certificates. Others mentioned

improvements to the storages browsers offer, such as

an API that removes records with specific keys.

Participants also proposed new APIs:

• to modify built-in APIs,

• to insert DOM overlay content not accessible

to page scripts to prevent webextension finger-

printability (Starov and Nikiforakis, 2017; Gulyas

et al., 2018),

18

See, for example, https://github.com/w3c/

webextensions/issues/103 for a related issue at W3C.

19

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Mozilla/

Add-ons/WebExtensions/API/dns

20

W3C issue tracker on the topic: https://github.com/

w3c/webextensions/issues/134

• to search all DOM, including all shadow DOMs

for certain elements, for example to detect page

artifacts of interest hidden in shadow DOMs,

• to improve consistent processing of the top level

documents and documents displayed in iframes,

• to enable secret handling,

• high-performance storage API,

• to improve icons displayed in dark themes,

• to allow background and content scripts to open

the webextension popup window.

5.6 Other Lessons Learned

Some developers decided to take another path instead

of migrating their webextension to Mv3. R06 devel-

oped 6 extensions and is bothered by several migra-

tions that browser extensions experienced in the past.

R06 had hoped that webextensions would unify the

code base of browser extensions, which was initially

successful for R06. However, R06 feels that such an

opportunity was lost with Mv3, as it requires learn-

ing from fragmented information and introduces an-

other platform to migrate to. As a result, R06 reimple-

mented the most important functionality of the main-

tained extensions as a user script of Greasemonkey

21

,

a webextension that allows customization of the way

webpages look and allows sharing user scripts

22

. Ef-

fectively, R06 added another layer that removes the

direct dependency on webextension APIs as long as

Greasemonkey continues to work. The cost is that

some functionality is not possible to implement in

Greasemonkey. Additionally, as the move to Grease-

monkey user scripts is not expected by browser ven-

dors, each user needs to manually replace the original

webextension with a Greasomonkey user script.

In one case, we reached an academic researcher

who merely stated that the extension is not meant to

be used by the general public and should be removed

from the public store. This raises questions of how

many similar projects are available in the stores, if in-

stalling such abandoned projects would introduce any

danger to the user, and how users can be protected

from installing potentially harmful extensions that are

not developed anymore.

6 CONCLUSION

Mv3 was supposed to promote secure and privacy-

respecting webextensions without limiting their pow-

21

https://www.greasespot.net/

22

https://wiki.greasespot.net/User Script Hosting

Developers’ Insight on Manifest v3 Privacy and Security Webextensions

25

ers (Google Inc., 2018). While we have seen some

positive effects of the migration, like one project

adding the support for a new browser and another

project unified code bases, most participants reported

the need to redesign their extensions without a pos-

itive impact on the users, dropped support for some

browsers, or need to maintain separate code bases for

the supported browsers.

Our research evaluates the reasons why webex-

tension developers are hesitant to change. Important

APIs are missing or are not mature and stable enough.

Additionally, Mv3 lacks new features and possibili-

ties, and does not motivate developers to switch to the

new APIs. Cross-platform compatibility is another

observed problem. Projects switch to separate code

bases for Chromium-based browsers or completely

give up support for these browsers.

Although some projects report short migration

time, others observe problems, including uncertain-

ties in the guarantees that content scripts run in time,

lost functionality due to missing APIs, slow and un-

safe means to store state, and bugs. Some types of

webextensions, like proxy managers and page con-

tent sanitizers, are affected less than various blockers,

cookie managers, and authentication tools. Partici-

pants also worried about the implications of storing

confidential information (e.g., cryptographic secrets,

information from private browser tabs) in the webex-

tension storages.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was funded through the NGI0 Entrust

Fund, a fund established by NLnet with financial sup-

port from the European Commission’s Next Genera-

tion Internet program, under the aegis of DG Commu-

nications Networks, Content and Technology under

grant agreement No 101069594 as JShelter Manifest

V3 project. This work was partly supported by the

Brno University of Technology grant FIT-S-23-8209.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, S. (2022). Helping or hindering? How browser

extensions undermine security. In ACM CCS ’22, page

23–37, New York, NY, USA.

Barnett, D. (2021). Chrome users beware: Man-

ifest V3 is deceitful and threatening. https:

//www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/12/chrome-users-

beware-manifest-v3-deceitful-and-threatening.

Borgolte, K. and Feamster, N. (2020). Understand-

ing the performance costs and benefits of privacy-

focused browser extensions. In ACM WWW ’20, page

2275–2286, New York, NY, USA.

Chen, Q. and Kapravelos, A. (2018). Mystique: Uncovering

information leakage from browser extensions. In ACM

CCS ’18, page 1687–1700, New York, NY, USA.

Chrome-stats.com (2025). Chrome extensions Manifest V3

migration status. https://chrome-stats.com/manifest-

v3-migration, last visit 2025-03-14.

Fass, A., Som

´

e, D. F., Backes, M., and Stock, B. (2021).

Doublex: Statically detecting vulnerable data flows in

browser extensions at scale. In ACM CCS ’21, page

1789–1804, New York, NY, USA.

Google Inc. (2018). Manifest V3. https://docs.google.com/

document/d/1nPu6Wy4LWR66EFLeYInl3NzzhHzc-

qnk4w4PX-0XMw8, DRAFT.

Gulyas, G. G., Some, D. F., Bielova, N., and Castelluccia,

C. (2018). To extend or not to extend: On the unique-

ness of browser extensions and web logins. In ACM

WPES’18, pages 14–27.

Hsu, S., Tran, M., and Fass, A. (2024). What is in the

chrome web store? In ACM ASIA CCS ’24, page

785–798, New York, NY, USA.

Kim, D. (2022). Find great extensions with new Chrome

Web Store badges. https://blog.google/products/

chrome/find-great-extensions-new-chrome-web-

store-badges/.

Miagkov, A., Gillula, J., and Cyphers, B. (2019). Google’s

plans for chrome extensions won’t really help secu-

rity. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/07/googles-

plans-chrome-extensions-wont-really-help-security.

Michael Schwarz, M. L. and Gruss, D. (2018). Javascript

zero: Real javascript and zero side-channel attacks. In

NDSSS’18.

O’Flaherty, K. (2019). Google confirms timeline for con-

troversial ad blocking plans. https://www.forbes.com/

sites/kateoflahertyuk/2019/06/25/google-confirms-

timeline-for-controversial-ad-blocking-plans/,

Forbes.

Pantelaios, N. and Kapravelos, A. (2024). Work-in-

progress: Manifest V3 unveiled: Navigating the new

era of browser extensions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/

abs/2404.08310.

Pol

ˇ

c

´

ak, L., Salo

ˇ

n, M., Maone, G., Hranick

´

y, R., and McMa-

hon, M. (2023). JShelter: Give me my browser back.

In SECRYPT’23.

Schaub, F., Marella, A., Kalvani, P., Ur, B., Pan, C., Forney,

E., and Cranor, L. F. (2016). Watching them watch-

ing me: Browser extensions’ impact on user privacy

awareness and concern. In Proceedings 2016 Work-

shop on Usable Security.

Smith, K. L. and Guzik, E. (2022). Developing privacy

extensions: Is it advocacy through the web browser?

Surveillance & Society, 20(1).

Starov, O. and Nikiforakis, N. (2017). Xhound: Quanti-

fying the fingerprintability of browser extensions. In

IEEE SSP’17, pages 941–956.

Teller, D. (2020). Why did mozilla remove xul add-

ons? https://yoric.github.io/post/why-did-mozilla-

remove-xul-addons/.

WEBIST 2025 - 21st International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

26