From Knowledge to Action: Understanding Coordination Practices in

Community-Led Urban Sustainability Projects

Leidy J. Palma-Huertas and Néstor A. Nova

a

Department of Information Science, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia

Keywords: Coordination Mechanisms, Knowledge Sharing, Urban Agriculture, Case Study.

Abstract: This study explores how community-based initiatives coordinate knowledge and collective action in urban

agriculture and organic waste management in Bogotá, Colombia. Grounded in coordination theory and

following a design science research approach, the study examines how interdependencies between tasks and

knowledge sources are addressed in grassroots sustainability projects. The discussion is supported by a case

study in a community-driven urban agriculture and organic waste recovery setting. We identify four core

community needs through qualitative methods: resource management, knowledge management,

collaboration, and organization. The findings show that coordination mechanisms are shaped by

sociotechnical variables such as the nature and origin of knowledge, its degree of codification, organizational

learning trajectories, and the availability of technological infrastructures. These factors configure dynamic

conditions that affect both the technical feasibility and social legitimacy of coordination practices. The study

highlights coordination as a situated and adaptive process, offering an analytical framework to understand

knowledge flows in community-led innovation.

1 INTRODUCTION

In community-driven sustainability initiatives,

particularly those related to urban agriculture and

organic waste management, coordination among

diverse actors is both essential and inherently

complex. In cities like Bogotá D.C., where public

institutions, academic sectors, and grassroots

organizations interact across fragmented governance

systems, aligning actions and knowledge flows

becomes a central challenge. This complexity affects

operational efficiency and long-term sustainability, as

well as the social appropriation of knowledge at the

community level. Knowledge sharing, information

circulation, and collaborative decision-making are

fundamental to the effectiveness of these initiatives.

However, poorly managed interdependencies among

tasks—such as compost production, resource

allocation, and cultivation planning—often result in

inefficiencies, duplicated efforts, and fragile

networks. Previous studies have shown that weak

coordination among stakeholders impedes waste

recovery strategies and limits the reach and continuity

of urban agriculture projects (Obule-Abila, 2020;

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2624-8314

Calderón and Rutkowski, 2020). Various studies

highlight that coordination failures represent one of

the main obstacles to sustainable development in

urban contexts. Among these challenges are the lack

of collaboration between institutions to achieve the

Sustainable Development Goals Fu et al. (2020),

ineffective communication between stakeholders

involved in waste management Soltani et al. (2015),

and the persistent disconnection between public,

private, and civil society sectors, which hinders the

achievement of positive environmental and social

outcomes (Batista et al., 2021). Understanding and

addressing these limitations is crucial for advancing

towards more integrated and effective urban

sustainability models. In addition, low levels of

awareness and weak stakeholder engagement in

waste classification processes further hinder

integrated solutions (Obule-Abila, 2020).

To address this challenge, this study draws upon

Coordination Theory Malone and Crowston (1990),

which defines coordination as the management of

interdependencies between activities. Coordination

mechanisms—such as standards, mediation, and

mutual adjustment—are defined as methods or tools

Palma-Huertas, L. J. and Nova, N. A.

From Knowledge to Action: Understanding Coordination Practices in Community-Led Urban Sustainability Projects.

DOI: 10.5220/0013668600004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

213-224

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

213

used to manage interdependencies performed by

different actors within a system (Malone and

Crowston, 1990). These mechanisms are shaped by

the sociomaterial practices in contextual dimensions,

meaning they need to adapt to the social and

technological context in which they are applied

(Nova, 2019). This paper contributes to that

perspective by examining community-driven

knowledge management in the context of peri-urban

agriculture. The empirical basis of this study is the

Terraza Verde Colombia project, launched in 2021

across three peri-urban communities in Bogotá: La

Flora and Alfonso López (Usme), and Palermo Sur

(Rafael Uribe Uribe). These communities engage in

organic waste transformation and food production

through participatory processes that combine

traditional practices, local governance, and the use of

digital tools. The study aims to analyze how

coordination unfolds in these settings and how actors

navigate the interplay between formal structures and

adaptive, community-led mechanisms. Accordingly,

this paper is guided by the following research

question: What sociotechnical and contextual factors

shape the selection and enactment of coordination

mechanisms for managing knowledge-intensive

interdependencies in community-based urban

agriculture and waste management projects?

To explore this question, the study adopts a

Design Science Research (DSR) approach,

incorporating participatory workshops, expert focus

groups, and field observations. The objective is not

only to map the relationships between coordination

mechanisms and the interdependencies they address,

but also to understand how communities decide

which mechanisms to apply in each context. This

includes examining the frequency of use and the

practical criteria that guide their selection—such as

accessibility, cultural alignment, technological

familiarity, or trust. These choices are often shaped

by localized knowledge, the nature of the information

being exchanged, and the dynamic conditions under

which community actors operate. By analyzing these

situated decisions, the study reveals how coordination

unfolds as a flexible and adaptive process within

knowledge-intensive environments. The rest of the

paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews

related research on coordination and knowledge

exchange. Section 3 outlines the research

methodology. Section 4 presents empirical findings.

Section 5 discusses their implications, and Section 6

offers conclusions and directions for future work.

2 RELATED RESEARCH

Coordination Theory (CT), proposed by Malone and

Crowston (1990), examines how tasks and activities

are efficiently managed among individuals,

organizations, or systems to achieve common goals

(Gonzalez, 2010). Coordination becomes essential

when interdependencies arise between activities, as

managing these relationships ensures effective

functioning. Malone et al., (1999) and Herman and

Malone (2003) reinforce this idea, emphasizing that

every interdependence presents an opportunity—or

necessity—for management. Thus, CT focuses on

interactions among actors, the processes (knowledge

sharing), resources (information), and decisions

(actions) that align their efforts. In knowledge

exchange, coordination refers to the mechanisms

facilitating collaboration and efficient interaction

among stakeholders (Nova, 2019). A well-structured

coordination process strengthens adaptability in

complex environments, fosters cooperation, and

enhances communication across diverse sectors. The

challenge lies in managing dynamic

interdependencies, which evolve over time and

require adaptable coordination strategies (Faraj and

Xiao, 2006). Effective coordination not only

optimizes resource utilization but also mitigates

inefficiencies arising from fragmented efforts.

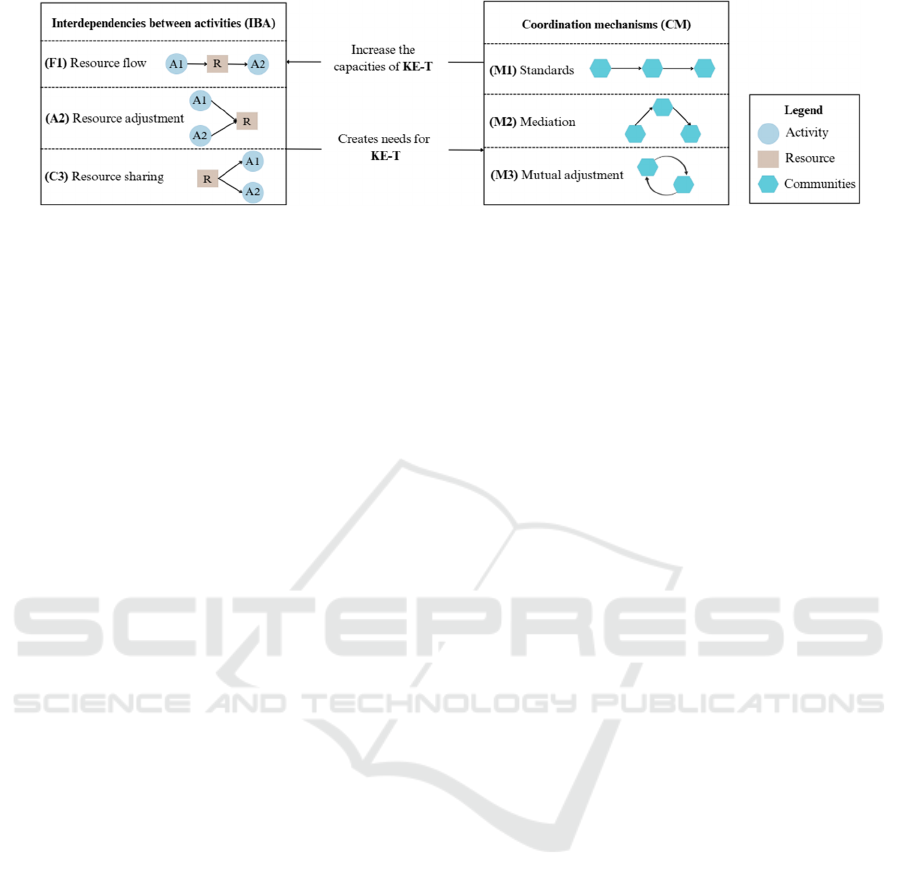

In Figure 1, the left section highlights the three

types of interdependencies between activities, which

create needs for knowledge sharing as well as

coordination. The right section presents the three

types of coordination mechanisms that manage these

needs, increasing the capacities for knowledge

sharing among various actors. According to Figure 1,

flow interdependence (F1) occurs when an activity

generates a resource that is utilized by another.

Meanwhile, adjustment interdependence (A2) arises

when multiple activities create the same resource.

Lastly, resource-sharing interdependence (C3) refers

to a scenario where multiple activities depend on a

common resource for their management.

In parallel, norm-based mechanisms (M1) refer to

formalized guidelines, action strategies, and

predefined objectives in which verbal interaction or

direct communication among agents is not required

for coordination (March and Simón, 1958; Galbraith,

1974). On the other hand, mediation-based

coordination (M2) involves the intervention of an

intermediary to facilitate the process between the

involved parties (Gonzalez, 2010). Finally, mutual

adjustment mechanisms (M3) rely on direct exchange

among participants, where adjustments and

corrections are managed internally without the

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

214

Figure 1: Coordination framework for knowledge exchange and transfer. Based on Gonzalez (2010).

intervention of an external agent (González, 2010).

Coordination theory in knowledge management

practices has been applied in diverse domains.

For example, Nova and González (2016)

examined knowledge transfer in inter-organizational

projects, identifying coordination gaps caused by

technological mismatches and the misalignment of

stakeholders’ expectations. Yu and Zhou (2017)

explored the role of coordination in cooperative

agricultural practices. Additionally, Brennecke et al.

(2024) analyzed informal coordination in knowledge-

intensive work. These studies highlight that

coordination relies on both formal structures and

informal interactions.

Coordination mechanisms are effective in

promoting knowledge exchange, collaboration,

problem-solving, and innovation (Ahmad, 2018). The

ability to share information and experiences fosters

trust, facilitates the resolution of shared challenges,

and enables solutions tailored to local needs (Keller

et al., 2013). However, weak regulatory structures

and insufficient governmental incentives limit the

development of robust knowledge-sharing platforms.

Strengthening legal frameworks and providing

financial support for collaborative initiatives could

enhance knowledge flow and reinforce urban

sustainability efforts Given these challenges,

coordination remains the cornerstone of effective

waste management and urban agriculture, ensuring

that knowledge exchange and resource utilization

contribute to long-term sustainability. Coordination

mechanisms are crucial in agriculture for organizing

collective efforts and optimizing resources. Examples

like China's "Enterprise plus Farmers" model Yu and

Zhou (2017) and cooperative pest management

(Stallman and James, 2015) demonstrate how

collaboration enhances efficiency and profitability. In

knowledge-intensive environments, formal

hierarchies combine with informal networks to

improve adaptive problem-solving (Brennecke et al.,

2024).Furthermore, studies show knowledge

coordination across diverse practices, even in public

organizations, relies on collaborative infrastructures

and shared spaces (Davies et al., 2015). Theoretically,

effective coordination also necessitates

understanding the social dynamics within

communities of practice, where shared meanings and

experiences are vital for overcoming organizational

barriers and fostering collective action (Brown and

Duguid, 2014). Effective coordination and

information flow are crucial for urban agriculture and

integrated organic solid waste management.

Currently, a lack of timely exchange and

collaboration among public entities, community

organizations, and private companies hinders waste

separation and sustainable initiatives (Dotoli and

Epicoco, 2019).

This inefficiency, a persistent challenge in waste

management, obstructs transitions to circular

economy models and limits urban resilience. The

absence of mechanisms linking waste generators,

operators, and authorities prevents integrated

strategies (Obule-Abila, 2020), compromising

information flow and joint decision-making. Inter-

institutional coordination, therefore, is essential for

facilitating knowledge exchange, collaborative

actions, and social transformation (Fu et al., 2020).

The literature underscores the importance of

knowledge coordination from a practical and social

standpoint. Brown and Duguid (2014) argue

organizations must coordinate not just formal units

but also communities of practice to overcome

epistemic barriers and foster knowledge flow. This

requires recognizing the centrality of shared practice

and collective learning. Sudirah (2022) study in

Indonesia exemplifies this, showing how

coordination among community, district, and

irrigation actors was key to addressing water and crop

challenges, boosting both technical efficiency and

local social networks. Conversely, deficient

coordination significantly limits sustainable urban

agriculture projects (Kanosvamhira, 2019).

Therefore, the lack of collaboration among public

institutions, social organizations, and communities

restricts their scalability. Establishing spaces for

dialogue and aligning objectives among actors is key

From Knowledge to Action: Understanding Coordination Practices in Community-Led Urban Sustainability Projects

215

to promoting sustainable initiatives that emerge from

the communities themselves (Méndez-Fajardo and

Gonzalez, 2014). More structured coordination not

only facilitates the integration of various actors but

also enables the optimization of resources and the

sharing of valuable learnings among them.

To understand the dynamics of coordination in

community urban agriculture and waste management,

this study draws on existing research by framing the

issue within a context of community needs that guide

coordination processes (Gonzalez, 2010; Nova,

2019). Previous studies have shown how formal and

informal coordination mechanisms operate in various

settings, highlighting the balance between structures

and relationships. Expanding on this perspective, the

present study introduces a framework of four

interrelated community needs that shape coordination

and knowledge management processes. These are:

Resource Management, focused on the access to and

organization of shared inputs; Knowledge

Management, related to the circulation and

appropriation of technical and community-based

knowledge; Collaboration Management, aimed at

facilitating joint actions among various actors; and

Organizational Management, related to leadership,

decision-making, and conflict resolution. These

categories allow for an examination of how specific

coordination mechanisms interact within community

practices, offering a more nuanced view of their

interdependencies. Building on the existing body of

research, this study seeks to explore the practical

application of coordination mechanisms for

knowledge exchange in community sustainability

projects.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

This research adopts the Design Science Research

(DSR) approach proposed by Hevner et al. (2004) to

analyze coordination and information exchange in

urban agriculture and waste management projects.

DSR is a research methodology centered on the

development and evaluation of practical solutions

that address specific domain challenges, combining

theoretical knowledge with empirical application.

The study follows the three iterative cycles proposed

by Hevner (2007): the relevance cycle, the rigor

cycle, and the design cycle. The study begins by

identifying the limitations in knowledge exchange

and coordination in urban agriculture initiatives,

particularly in the Terraza Verde project.

Stakeholders, including community members and

experts, contribute insights regarding the challenges

in organizing, sharing, and utilizing knowledge

related to waste management and urban farming. The

research integrates theoretical foundations from

coordination theory Malone and Crowston (1990) and

knowledge management to systematically examine

coordination mechanisms in this context.

3.1 Case Study Selection

The study employs a case study approach to explore

collaborative knowledge-sharing practices and

coordination mechanisms within peri-urban

agriculture communities in Bogotá, Colombia. The

selected case study focuses on three communities

participating in the Terraza Verde project: UPZ La

Flora, Alfonso López (Usme), and Palermo Sur

(Rafael Uribe Uribe). These communities are situated

at the urban-rural interface, where socio-economic

and environmental dynamics converge, influencing

resource management and agricultural activities.

The case study follows Yin (2009)

methodological framework, which is suitable for

addressing "how" and "why" questions within

contemporary social contexts. Field observations and

direct engagement with local stakeholders were

essential to understanding the interactions shaping

agricultural knowledge exchange. Through in-depth

interaction with community members, trust-building

facilitated open exchanges of experiences and local

knowledge. This ethnographic engagement allowed

for an integrative analysis of social cohesion,

adaptive capacity, and sustainability practices within

the communities. The presence of formal and

informal networks for knowledge dissemination was

observed, highlighting the role of community-driven

training initiatives supported by public and private

institutions. The case study provides a practical

perspective on knowledge coordination in urban

agriculture, examining the influence of institutional

collaborations, grassroots initiatives, and digital tools

for information exchange. It also offers insights into

coordination mechanisms tailored to the

sociomaterial conditions of peri-urban farming

ecosystems.

3.2 Data Collection

To deepen the understanding of knowledge exchange

mechanisms in these communities, a mixed-method

approach was employed, combining qualitative and

quantitative techniques. The case study selection

informed the data collection process, ensuring that the

identified challenges and knowledge-sharing

practices

were adequately explored. Data were

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

216

collected through participatory workshops with

community members engaged in the Terraza Verde

project (see Figure 2), focusing on identifying

coordination challenges, knowledge gaps, and

possible solutions to improve information flow and

stakeholder collaboration. A focus group involving

experts in urban agriculture, waste management, and

information systems was also organized to validate

the findings and refine the analysis.

Figure 2: Sharing knowledge by community leaders.

Direct observations were conducted in the three

selected communities to document knowledge-

sharing practices, coordination mechanisms, and

stakeholder interactions. Reports, policy documents,

and previous studies related to urban agriculture and

waste management in Bogotá were analyzed to

contextualize the findings and validate the research

framework. The research data supporting this study is

available at [https://osf.io/a9hy6/files/osfstorage].

3.3 Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using a combination

of qualitative coding and network analysis to identify

patterns in knowledge exchange and coordination.

Thematic analysis was conducted by transcribing and

analyzing data from workshops and focus groups,

identifying recurring themes related to coordination

challenges, knowledge transfer barriers, and

community-driven solutions. Findings were validated

by cross-referencing data from multiple sources,

including interviews, observations, and document

analysis, to ensure consistency and reliability.

4 FINDINGS

As a result of these workshops, four community needs

were supported: Resource Management, Knowledge

Management, Collaboration Management, and

Organizational Management. Based on these needs,

eleven interdependencies between activities were

identified and categorized as follows: two related to

flow (F1), three to adjustment (A2), and six to

resource exchange (C3). Additionally, the

relationships between the interdependencies and the

coordination mechanisms within each community

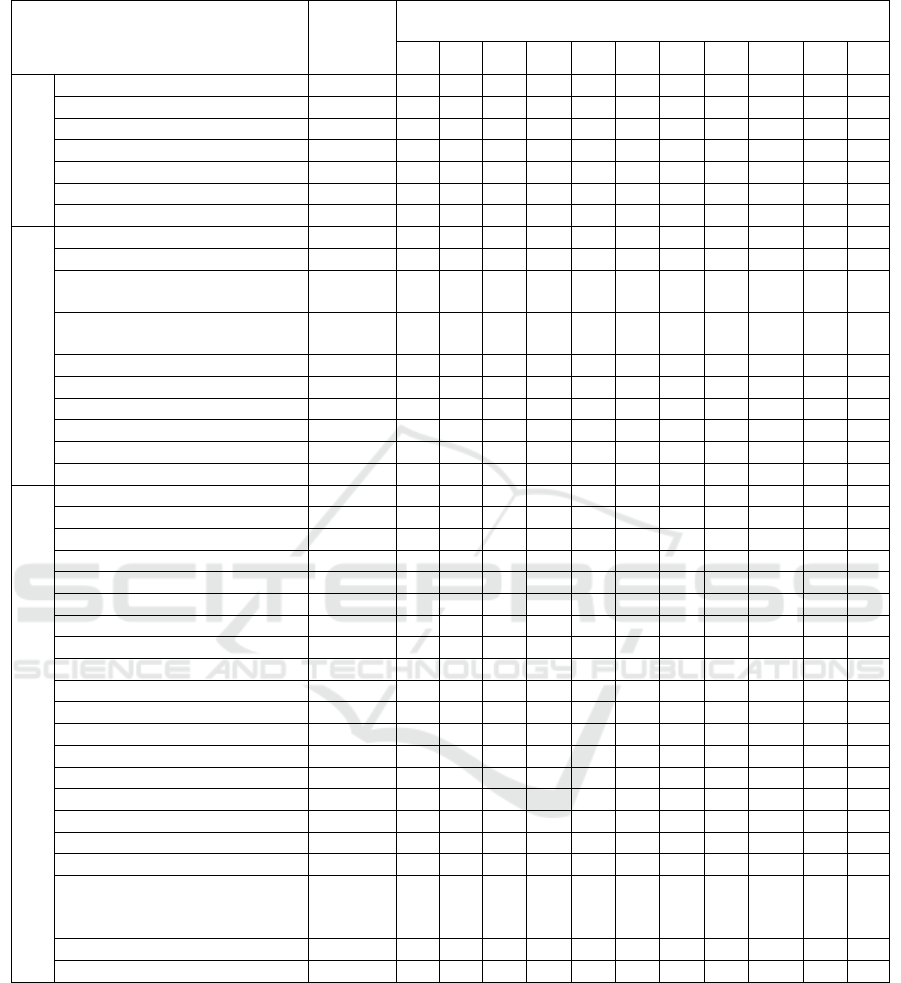

need were established. Table 1 shows how

coordination mechanisms are linked to each

community's need and their corresponding

interdependencies. The purpose of this case study was

twofold: first, to identify the coordination

mechanisms used to manage each interdependency.

Second, to determine the extent to which a particular

mechanism is selected within the overall set and the

criteria that guide that selection. The correlation

between coordination mechanisms and

interdependencies is presented in Table 1, which

includes a ranking of the use of the mechanism with

respect to the interdependency and the community

need to which it is applied. This information made it

possible to identify coordination patterns linked to

each type of interdependency and community need,

facilitating the analysis of the mechanisms used and

the criteria guiding their selection.

4.1 Community Need 1: Resource

Management

This need revealed two resource-sharing

interdependencies (C3) critical to the operation of the

community garden. The first (c3a) involves collective

participation in and exchange of materials and labor

required for various stages of the garden’s

development: from its initial design and formalization

to compost and food production. Coordination

practices identified in this context include collective

work sessions rooted in traditional practices

(Communities of communitarian experts), which are

oriented toward solidarity and community self-

management, and align local labor efforts with shared

goals and territorial realities. Additionally, expert

communities facilitate the exchange of technical

knowledge and the joint construction of solutions

between institutional and community actors. Day-to-

day coordination is maintained through diverse

communication strategies, such as WhatsApp groups,

phone calls, video conferencing, face-to-face

gatherings, and public announcements made through

local institutions like the parish. These practices

enabled real-time interaction despite geographic

From Knowledge to Action: Understanding Coordination Practices in Community-Led Urban Sustainability Projects

217

dispersion and asynchronous availability. The second

interdependency (c3b) refers to the distribution of

agricultural tools and products—such as seeds,

fertilizers, and work implements—by the Botanical

Garden, the UAESP, and the Pontificia Universidad

Javeriana. Coordination in this domain is achieved

through both formal and informal instances of

interaction, including scheduled coordination

meetings, and through the roles assumed by

institutional and community leaders who guide

resource allocation. Communication between actors

is further reinforced through locally adapted methods

such as community notice boards, interpersonal

exchanges, and direct participation in community

events, ensuring that information reached all

stakeholders involved in the distribution process.

Finally, a fit interdependency (A2) was identified

in relation to the collection and contribution of

organic material for composting by the community

(a2a). This involves the aggregation of household and

local organic waste for transformation through

composting and vermiculture techniques. To manage

this process, the community follows established

composting protocols and guidelines co-developed

with institutional actors. Coordination efforts were

supported by the planned use of the CERES (a mobile

application for agriculture management), periodic

follow-ups by coordination committees, and the

participation of community leaders responsible for

overseeing adherence to procedures. These activities

are reinforced by informal but effective practices such

as house-to-house communication, in-person

discussions during community events, and

institutional training sessions. To enhance local

capabilities in organic waste management, additional

educational initiatives and personal development

workshops are envisioned for future implementation.

4.2 Community Need 2: Knowledge

Management

Two resource-sharing interdependencies (C3) are

identified in relation to the community’s acquisition

of knowledge on waste separation and crop

cultivation (c3c). Coordination practices include

printed materials such as booklets, guides, and

training programs that structure and reinforce

community learning. These tools support knowledge

circulation, encourage the involvement of new

participants, and help consolidate a shared foundation

that sustains long-term community action in waste

management and agriculture.

Complementary practices involve digital tools,

such as the moderate use of websites by gardeners to

expand knowledge, address specific questions, or

explore cultivation techniques. Though not widely

adopted, these platforms supplement other learning

formats and create access points to broader

information networks. Coordination is also supported

by everyday peer interaction, including neighbor-to-

neighbor phone calls, community workshops, online

and in-person courses, WhatsApp groups, and voice-

based communication. Institutional actors, including

universities and research centers, play a key role in

delivering technical training, enabling communities

to maintain continuous knowledge exchange and

collective learning through direct and dynamic forms

of engagement. A second interdependency (c3d)

refers to the availability of educational resources on

waste management, compost production, and the

cultivation of vegetables, herbs, tubers, and medicinal

plants. Booklets, work plans, and instructional

documents offer structured guidance, while other

supports include occasional use of the CERES mobile

application and educational websites. Knowledge

also circulates informally through neighborly

dialogue, video tutorials on platforms like YouTube

and Facebook, and participation in local meetings.

Together, these mechanisms reflect the varied ways

knowledge is adapted and shared within the

community, contributing to an active and

decentralized learning environment.

In addition, two resource-flow interdependencies

(F1) are identified. The first (f1a) addresses the

exchange of knowledge and experience related to

crop cultivation. Coordination tools include printed

guides and training programs, as well as coordination

committees, collective work events, expert networks,

and instant messaging. These support cross-learning

among participants and strengthen connections

between actors engaged in agricultural practices. The

second interdependency (f1b) refers to access to

reliable and updated sources of information.

Coordination is driven by peer-led communication

such as phone calls, community workshops, experts

mobility, WhatsApp groups, and education-oriented

activities like talks and personal development

sessions. These mechanisms support sustained access

to shared knowledge and enable collaborative

problem-solving within the community context.

4.3 Community Need 3: Collaboration

Management

This need reveals two resource-sharing

interdependencies (C3) relevant to collaborative

decision-making and collective practices around crop

cultivation and organic waste management. The first

(c3e) focuses on how individual and group decisions

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

218

Table 1: Interdependencies and coordination mechanisms in the case study.

COORDINATION MECHANISMS

(CM)

No.

COM-

MUNITY

NEEDS

INTERDEPENDENCIES BETWEEN ACTIVITIES (IBA)

f1a f1b a2a a2b a2c c3a c3b c3c c3d c3e c3f

STANDARDS (M1)

Booklets 2,3

2 1 1 1 1

Books 2,3

2 2 P

Training programs 2,3

1 2,P 2 2

Policies 2,3

1 1

Documents and work

p

lans 4

2 F F

Protocols 1,3,4

1 3 2.F

Printed

g

uides 2,3

2 1 2

MEDIATION (M2)

Coordination committees 1,2,4

1 1 2 P,F 1,F

Technical reports 3

1

Collective work events

(mingas)

1,2,3

1 3 1

Communities of community

ex

p

erts

1,3

3 2 2 1

CERES mobile a

pp

lication 1,2

F 3,F

Websites 2,3

2 2 2,F 3,F

Software programs (office suite) 4

2 F

Hierarchies 1,2,3

1 1 1 1 1 2

Authorit

y

fi

g

ures 1,2,3

2 2 1 1 2 2

Internet search s

y

stems 2,3

3 2

MUTUAL ADJUSTMENT (M3)

Instant messaging 1,2

2 2

Phone calls 1,2

1 1 1 1 1

Meetings with local leaders 2,4

3 3,F

Communit

y

worksho

p

s 2,3,4

1 1 1 2,F 1 1 1

Nei

g

hborl

y

dialo

g

ue 2,3,4

1 1 1 1 1 1

Online and in-

p

erson courses 2,3,4

2 2 1

Experts mobilit

y

1,2,3

2 2 1

Video conferencing 1

2

WhatsApp groups 1,2,3,4

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1,F

Posters 1

2 2,F

Voice-

b

ased communication 1,2,3,4

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2

Video tutorials on YouTube 2,3,4

2 2 1 1

Video tutorials on Faceboo

k

2

2 2

Face-to-face gatherings 1,2,3,4

1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1

e-mail 2

3

Discussion / debate 2,3

3,F 1

Institutional trainin

g

sessions 1,2,3,4

1 1 1 2 1 1

Open forums / public talks 2,3,4

2 2 2,F

Educational initiatives /

personal development

workshops

1,2,3,4

2 F 1 F

Parish notices 1

2,P 1

Personnel rotation 4

1

are made in these processes. Coordination practices

include the use of community protocols and policies

that provide structure and clarity for everyday

activities. While formal mediation mechanisms—

often associated with hierarchies or authority

figures—are used infrequently, mutual adjustment

practices play a central role. These include neighborly

dialogue, open debate, and face-to-face meetings

between gardeners and experts, which facilitate

shared understanding and collaborative decision-

making within the community.

The second interdependency (c3f) involves the

network of relationships between community

members and external actors such as churches,

companies, foundations, and universities. These

connections enhance the community’s social fabric

and expand its access to resources, skills, and

opportunities that would otherwise remain out of

From Knowledge to Action: Understanding Coordination Practices in Community-Led Urban Sustainability Projects

219

reach. Through these links, gardeners strengthen their

technical capacities and broaden the scope and

sustainability of their collective initiatives. In this

context, coordination mechanisms are diverse and

consistently applied. Printed guides and training

programs provide clear guidance for local practices.

Technical reports, collective work events (mingas),

and internet search systems enable articulation

between internal and external stakeholders.

Knowledge exchange also occurs through more

adaptive and informal means such as community

workshops, YouTube tutorials, WhatsApp groups,

and institutional training sessions. Looking ahead, the

integration of new interaction spaces—such as open

forums and public talks—is anticipated. These would

support continuous learning and allow communities

to respond more flexibly to evolving challenges. The

combination of formal, informal, and context-

sensitive coordination strategies enables actors to co-

produce knowledge, resolve tensions, and sustain

collaborative efforts over time. This highlights the

importance of fostering both internal cohesion and

external connectivity as key drivers of effective

community-based collaboration.

4.4 Community Need 4: Organizational

Management

This need reveals two fit interdependencies (A2)

associated with the structuring and governance of

collective action. The first (a2b) concerns community

inclusion in the selection of leaders and representative

figures. Coordination is supported by planning

documents and work plans that formalize

organizational structures and define roles. The

coordination committees and software programs

(office suite) also contribute to the systematization of

information, organizing tasks and enabling a more

structured follow-up of ongoing initiatives. These

mechanisms strengthen procedural transparency and

support community governance. In parallel, mutual

adjustment practices—such as neighbor-to-neighbor

dialogue, online and in-person courses, and personnel

rotation—promote flexible knowledge articulation

and ongoing adaptation to changing conditions. These

interactions reinforce collaborative dynamics and

sustain shared learning processes that underpin

community-based knowledge management.

The second interdependency (a2c) centers on

addressing conflicts, challenges, and community-

level negotiations that arise during agricultural work

and waste management. In this case, effective

resource adjustment becomes essential to maintaining

continuity and responsiveness in the face of emerging

obstacles. While formal protocols are part of the

organizational repertoire, their application remains

sporadic and context dependent. Defined roles within

hierarchical structures support mediation practices

that facilitate conflict resolution and guide decision-

making. These approaches provide stability,

especially in complex or tense situations. However,

mutual adjustment remains a key coordination

strategy. Face-to-face gatherings and the use of

digital resources such as YouTube tutorials foster

informal interaction, fluid information exchange, and

rapid collective responses to emerging needs. These

flexible mechanisms do not rely on formal

procedures, which allows participants to respond

effectively to challenges and maintain strong levels of

engagement.

Altogether, the combination of formal tools,

mediated roles, and informal practices ensures that

organizational processes are both structured and

adaptable. This hybrid coordination approach

supports shared leadership, enhances responsiveness,

and promotes the development of resilient and

participatory community governance systems. The

case study not only identifies the coordination

practices implemented to manage each

interdependency associated with the community

needs but also examines how frequently these

mechanisms are chosen from the broader repertoire

and the criteria that guide such selection. Table 1

illustrates the relationship between coordination

practices and the types of interdependencies

observed, using a scale from 1 (frequently used) to 3

(rarely used). Additionally, the symbols "P" and "F"

indicate whether a mechanism was previously applied

or is projected for future implementation, as reported

by participants. While these markers provide insight

into the possible evolution and adaptability of

coordination strategies, a deeper analysis of these

trajectories lies beyond the scope of this article.

Finally, the selection and adequacy of

coordination mechanisms in response to community

needs and their associated interdependencies are

influenced by several factors related to the

characteristics of the information and knowledge

involved. These include the volume of information to

be managed, its public or private nature, and its

specific attributes—such as format, level of detail,

organization, accuracy, and timeliness. The diversity

of formats—ranging from written documents and

visual materials to multimedia content and technical

plans—also conditions the suitability of standard-

based tools, mediated interactions, or mutual

adjustment practices. Recognizing and addressing

these variables enhances the effectiveness of

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

220

coordination, strengthens knowledge exchange, and

allows communities to adopt flexible and context-

sensitive strategies for managing shared tasks and

solving complex challenges.

5 DISCUSSION

The coordination model developed in this study

reveals a strategic coexistence between ICT-based

coordination mechanisms and traditional, face-to face

practices rooted in community dynamics. This dual

approach reflects an adaptive response to the

sociomaterial conditions of the communities

involved, where knowledge circulation depends on

both digital platforms and in-person interactions

(Nova and González, 2016). Tools such as

WhatsApp, video conferencing, institutional

websites, and mobile applications enhance the speed

and breadth of information exchange. However,

physical coordination mechanisms—such as

traditional community work gatherings, notice

boards, community meetings, and word-of-mouth

communication—remain essential for strengthening

social bonds, building trust, and ensuring the

collaborative management of local knowledge.

This finding aligns with recent studies that

emphasize the importance of hybrid coordination

environments, where formal structures and informal

dynamics interact to foster knowledge exchange in

decentralized contexts (Brennecke et al., 2024b). In

such environments, digital tools extend the reach of

technical information and facilitate access to broader

networks, while traditional practices enable

contextual interpretation and promote community

engagement. However, the successful integration of

these tools depends heavily on the capacity of actors

to align technological resources with local values,

communication preferences, and relational norms

(Toukola and Ahola, 2022).

In the case of the Terraza Verde project, the use

of ICTs has helped expand networks, access new

sources of information, and streamline some

coordination tasks. Yet, the empirical evidence shows

that many information flows within these

communities still depend on external facilitators—

such as universities, NGOs, and local government

officials—to be fully consolidated and appropriated.

This observation supports the argument that the

appropriation of technology in community contexts is

not only a matter of infrastructure availability, but

also of continuous support, relational trust, and

contextual adaptation (Baladron, 2021), considering

that the most effective interventions tend to

incorporate mechanisms for building trust among

actors, strengthening local capacities, and

implementing flexible frameworks that allow

strategies to be adjusted in response to the social,

organizational, and territorial changes each

community experiences.

This aligns with the notion of organizational

flexibility as a key condition for effective knowledge

exchange in community settings. Flexible

coordination structures, capable of adjusting to

changing environments, reconfiguring alliances, and

absorbing contextual pressures, are essential to

sustaining innovation and community resilience (Li et

al., 2017). From this perspective, the proposed

coordination model should be understood not as a

static structure, but as a dynamic framework that

evolves with the transformations experienced by the

community. Moreover, the analysis of coordination

practices highlights several challenges for

community-based knowledge management. Beyond

ensuring access to information, effective knowledge

management requires mechanisms that contextualize

knowledge, embed it in local practices, and transform

it into actionable insights.

This involves managing not only the technical

dimensions of coordination, but also the social and

relational aspects that condition how knowledge is

shared, validated, and applied (Choi et al., 2008). The

role of communities of practice becomes particularly

relevant in this regard. As Wenger-Trayner and

Wenger-Trayner (2015) suggest, the value created in

community settings depends on the integration of

knowledge into everyday interactions, learning

routines, and shared meaning-making processes.

These communities foster collective knowledge

management by directly linking learning with

performance and enabling the circulation of both tacit

and explicit knowledge. Because of their flexible and

autonomous nature, they can transcend formal

institutional boundaries and foster dynamic

knowledge flows that respond to evolving local needs

(Cohendet et al., 2015). However, this also introduces

a set of challenges for traditional institutions with

hierarchical structures.

When coordination mechanisms fail to adapt to

local dynamics, they may fragment knowledge flows,

reproduce inequalities in information access, and

erode the trust necessary for collective action as

shown in (Nova and González, 2016; Palma-Huertas,

2024). In this study, such tensions became evident in

activities that simultaneously fulfill multiple roles—

such as community training workshops, which not

only serve to disseminate information but also foster

experience-sharing and strengthen social cohesion.

From Knowledge to Action: Understanding Coordination Practices in Community-Led Urban Sustainability Projects

221

Therefore, the complexity and multifunctionality of

these spaces should be recognized and supported

through coordination mechanisms that are both

flexible and inclusive.

In this sense, coordination should be understood

as an inherently social and adaptive process that

articulates local knowledge, situated practices, and

trust-based relationships. It plays a crucial role in

enabling environmental governance at the

community level, where diverse actors and

knowledge must align around shared goals.

Accordingly, designing coordination mechanisms for

community-based knowledge management requires

embracing organizational flexibility, valuing

territorial knowledge, and promoting inclusive,

dialogical, and collaborative practices (Lange et al.,

2020). Such a shift calls for the development of

sustainable knowledge ecosystems—spaces that go

beyond information transfer and actively promote

social innovation, critical knowledge appropriation,

and collective resilience. In peri-urban contexts,

where institutional support may be fragmented and

social capital is unevenly distributed, this means

building interaction platforms that empower

communities to self-organize, manage knowledge

autonomously, and strengthen their adaptive capacity

to face environmental, economic, and social

challenges. This study also confirms that coordination

mechanisms in community settings cannot be reduced

to standardized instruments or rigid structures.

Instead, they must be conceived as adaptive processes

that accommodate diversity, respect local rhythms,

and evolve with the needs and priorities of the

collective. Only through such a sensitive and flexible

approach can coordination strategies foster equitable,

sustainable, and transformative knowledge processes

in peri-urban communities.

Based on these findings, we propose three design

guidelines to strengthen Information and

Communication Technology (ICT)-based

coordination mechanisms within community

contexts. First, it is crucial to foster digital co-

creation. This involves enabling local actors to

actively participate in the design and adaptation of

digital content and tools. Such participation promotes

knowledge appropriation and contextual relevance.

Second, we recommend incorporating technological

intermediation structures. These could include

community facilitators or institutional partners who

can support the progressive integration of

technologies and effectively reduce gaps in access

and usage. Third, activating distributed knowledge

networks through digital community micro-platforms

is essential. These platforms would function as

autonomous nodes for managing local information in

a decentralized, resilient, and scalable manner (Lange

et al., 2020) . These guidelines aim to advance more

inclusive, adaptive, and sustainable forms of

coordination. Here, technology not only mediates

information flows but also enhances collective

learning, local autonomy, and the co-creation of

solutions in direct dialogue with the communities

themselves.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that Coordination Theory

offers a robust analytical framework for examining

knowledge management in community-based

settings, particularly within urban agriculture and

organic waste recovery initiatives. By analyzing

activity interdependencies and the coordination

mechanisms employed to manage them, we identified

how communities develop context-sensitive

arrangements that are not solely dependent on formal

structures, but also on trust-based relationships and

locally embedded knowledge. Our findings indicate

that the selection of coordination mechanisms is

neither arbitrary nor purely functional. Rather, it

emerges from the interaction of sociotechnical

variables such as the epistemological nature of

knowledge (tacit or explicit); the source of knowledge

(technical, ancestral, or Indigenous); the degree of

information structuring and codification (e.g.,

informal knowledge transmitted through oral

practices vs. formally documented technical

protocols); organizational learning trajectories (e.g.,

prior experience with empowerment, self-

management, or collective organization); and the

availability of technological infrastructures (e.g.,

limited internet access or lack of digital tools to

support communication and knowledge sharing).

These variables configure dynamic conditions that

determine both the technical feasibility and social

legitimacy of each coordination mechanism.

Accordingly, coordination must be understood as a

situated practice in which collaboration and

knowledge circulation rely on actors’ capacity to

mobilize cognitive, relational, and technological

resources.

The case study reveals how community-led

initiatives can generate tangible outcomes by

combining knowledge sharing, collective

organization, and sustainable practices. These

processes contribute to food resilience and the

localized management of organic waste, while also

strengthening community governance structures and

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

222

collaborative learning dynamics. Although derived

from a specific context, the findings suggest

coordination patterns and boundary conditions

relevant for broader application. This study, focused

on communities in Usme and Rafael Uribe Uribe

(Bogotá), provides analytical principles and design

guidelines for ICT-based coordination. However,

applying these insights elsewhere requires a critical

understanding of local dynamics, institutional

conditions, and specific technological contexts.

Future research should thus examine how

coordination mechanisms evolve in diverse

sociotechnical environments, particularly with

Industry 4.0 technologies and the potential of

generative AI to enhance knowledge flow, task

assignment, and real-time collective decision-making

in community settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND

FUNDING

We would like to thank the members of the Terraza

Verde project, the local communities. This work was

supported by Pontificia Universidad Javeriana,

Bogotá, Colombia, under grant number 2025-I (ID

20942).

REFERENCES

Ahmad, F. (2018). Knowledge sharing in a non-native

language context: Challenges and strategies. Journal of

Information Science, 44(2), 248–264.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551516683607

Baladron, M. I. (2021). Apropiación de tecnologías en las

redes comunitarias de internet latinoamericanas.

Tripodos, 46, 59–76. https://doi.org/10.51698/t

ripodos.2020 .46p59-76

Batista, M., Goyannes Gusmão Caiado, R., Gonçalves

Quelhas, O. L., Brito Alves Lima, G., Leal Filho, W.,

& Rocha Yparraguirre, I. T. (2021). A framework for

sustainable and integrated municipal solid waste

management: Barriers and critical factors to developing

countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 312, 127516.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127516

Brennecke, J., Coutinho, J. A., Gilding, M., Lusher, D., &

Schaffer, G. (2024a). Invisible Iterations: How Formal

and Informal Organization Shape Knowledge Networks

for Coordination. Journal of Management Studies,

62(2), 706–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.13076

Brennecke, J., Coutinho, J. A., Gilding, M., Lusher, D., &

Schaffer, G. (2024b). Invisible Iterations: How Formal

and Informal Organization Shape Knowledge Networks

for Coordination. Journal of Management Studies,

62(2), 706–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.13076

Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (2014). Knowledge and

Organization: A Social-Practice Perspective.

Organization Science, 12(2), 198–213.

https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.2.198.10116

Calderón, A. J., & Rutkowski, E. W. (2020). Waste

management drivers towards a circular economy in the

global south – The Colombian case. Waste

Management, 110, 53–65.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.05.016

Choi, S. Y., Kang, Y. S., & Lee, H. (2008). The effects of

socio-technical enablers on knowledge sharing: an

exploratory examination. Journal of Information

Science, 34(5), 742–754.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551507087710

Cohendet, P., Grandadam, D., Simon, L., & Capdevila, I.

(2015). Epistemic Communities, Localization and the

Dynamics of Knowledge Creation. Economic

Geography, 14(5), 1–26.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2

687694

Davies, H. T., Powell, A. E., & Nutley, S. M. (2015).

Mobilising knowledge to improve UK health care:

learning from other countries and other sectors – a

multimethod mapping study. Health Services and

Delivery Research, 3(27), 1–190.

https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr03270

Dotoli, M., & Epicoco, N. (2019). Emerging Issues in

Control, Decision, and ICT Approaches for Smart

Waste Management. 2019 6th International

Conference on Control, Decision and Information

Technologies (CoDIT), 446–451. https://doi.org/1

0.1109 /CoDIT.2019.8820603

Faraj, S., & Xiao, Y. (2006). Coordination in Fast-Response

Organizations. Management Science, 52(8), 1155–

1169. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20110591

Fu, B., Zhang, J., Wang, S., & Zhao, W. (2020).

Classification–coordination–collaboration: a systems

approach for advancing Sustainable Development

Goals. National Science Review, 7(5), 838–840.

https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwaa048

Galbraith, J. R. (1974). Organization design: An

information processing view. Interfaces, 4(3), 28–36.

https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.4.3.28

Gonzalez, R. A. (2010). A framework for ICT-supported

coordination in crisis response [Delft University of

Technology].

Herman, G., & Malone, T. W. (2003). What Is in the

Process Handbook? In Organizing Business

Knowledge: The MIT Process Handbook. (pp. 1–38).

http://ccs.mit.edu/papers/pdf/wp221.pdf

Hevner, A. R. (2007). A Three Cycle View of Design

Science Research. Scandinavian Journal of

Information Systems, 19(2), 1–7.: http://aisel.ais

net.org/sjis/vol19/iss2/4

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004).

Design Science in Information Systems Research. MIS

Quarterly, 28(1), 75–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/

25148625

Kanosvamhira, T. P. (2019). The organisation of urban

agriculture in Cape Town, South Africa: A social

From Knowledge to Action: Understanding Coordination Practices in Community-Led Urban Sustainability Projects

223

capital perspective. Development Southern Africa,

36(3), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.

2018.1456910

Keller, K. M., Yeung, D., Baiocchi, D., & Welser, W.

(2013). Barriers to Information Sharing. Facilitating

Information Sharing Across the International Space

Community: Lessons from Behavioral Science, 3–10.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt5hhw06.8

Lange, P. de, Goschlberger, B., Farrell, T., Neumann, A. T.,

& Klamma, R. (2020). Decentralized Learning

Infrastructures for Community Knowledge Building.

IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 13(3),

516–529. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2019.2963384

Li, Y., Li, P. P., Wang, H., & Ma, Y. (2017). How Do

Resource Structuring and Strategic Flexibility Interact

to Shape Radical Innovation? Journal of Product

Innovation Management, 34(4), 471–491.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12389

Malone, T. W., & Crowston, K. (1990). What is

coordination theory and how can it help design

cooperative work systems? Proceedings of the 1990

ACM Conf. on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work

- CSCW ’90, 357–370. https://doi.org/10

.1145/99332.99367

Malone, T. W., Crowston, K., Lee, J., Pentland, B., &

Dellarocas, C. (1999). Tools for Inventing

Organizations: Toward a Handbook of Organizational

Processes. SURFACE at Syracuse University, 1–21.

March, J. G., & Simón, H. A. (1958). Organizations.

Méndez-Fajardo, S., & Gonzalez, R. A. (2014). Actor-

Network Theory on Waste Management. International

Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological

Innovation, 6(4), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.4018

/ijantti.2014100102

Nova, N. A. (2019). Sociomaterial design of coordination

in knowledge sharing: A heritage KMS reference

architecture [Pontificia Universidad Javeriana].

http://hdl.handle.net/10554/44933.

Nova, N. A., & González, R. A. (2016). Coordination

Problems in Knowledge Transfer: A Case Study of

Inter-Organizational Projects. Proceedings of the 8th

International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management, 60–69. https://doi.org/10.5220/00

06053200600069

Obule-Abila, B. (2020). Knowledge management approach

for sustainable waste management [University of

Gävle].

Palma-Huertas, L. J. (2024). AGRORGÁNICOKGC grafo

de conocimiento comunitario para la agricultura urbana

y gestión integral de residuos sólidos orgánicos en

comunidades periurbanas de Bogotá D.C [Pontificia

Universidad Javeriana].

Soltani, A., Hewage, K., Reza, B., & Sadiq, R. (2015).

Multiple stakeholders in multi-criteria decision-making

in the context of Municipal Solid Waste Management:

A review. Waste Management, 35, 318–328.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2014.09.010

Stallman, H. R., & James, H. S. (2015). Determinants

affecting farmers’ willingness to cooperate to control

pests. Ecological Economics, 117, 182–192.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.07.006

Sudirah. (2022). Cross-Sector Coordination of Village

Community Social Institutions and Agricultural

Intensification. Proceedings of the International

Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations

Management, 695–706. https://doi.org/10.46254

/AU01.20220180

Toukola, S., & Ahola, T. (2022). Digital tools for

stakeholder participation in urban development

projects. Project Leadership and Society, 3, 100053.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plas.2022.100053

Wenger-Trayner, B., & Wenger-Trayner, E. (2015).

Introducción a las comunidades de práctica: una breve

descripción del concepto y sus usos. 1–9.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case Study Research: Design and

Methods (SAGE Publications).

Yu, D., & Zhou, R. (2017). Coordination of Cooperative

Knowledge Creation for Agricultural Technology

Diffusion in China’s “Company Plus Farmers”

Organizations. Sustainability, 9(10), 1906.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101906

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

224