Embedding Knowledge Management in R&D Capability

Transformation in Software Startups

Nabil Georges Badr

a

Independent Researcher and Engaged Scholar, Jacksonville, U.S.A.

Keywords: Knowledge Management, Organizational Development, Organizational Transformation, Action Research.

Abstract: Organizational development drives growth, especially for startups. This study presents a longitudinal action

research engagement exploring the strategic integration of Knowledge Management (KM) practices within

Organizational Development (OD) initiatives to catalyse scalable transformation in a software startup.

Grounded in dynamic capability theory and implemented through the continual improvement framework, the

intervention addressed operational inefficiencies, role ambiguity, and delivery challenges across R&D

functions. By layering KM methodologies, such as centralized repositories, stakeholder-driven assessments,

and iterative feedback loops into OD processes, the engagement reconstructed team structures, codified

decision-making routines, and fostered a culture of collaborative innovation. Through cross-functional

restructuring, strategic role definition, and embedded governance practices, KM was operationalized as both

an infrastructural asset and a dynamic capability enabler. The findings underscore KM’s pivotal role in

enhancing adaptability, aligning leadership vision with execution, and sustaining high-performance

trajectories under volatile growth conditions. This research contributes to startup literature by framing KM

not merely as a support function, but as a strategic lever for organizational resilience, learning, and value

creation.

1 INTRODUCTION

In today’s volatile and fast-paced startup ecosystems,

strategic organizational development (OD) has

emerged as a critical determinant of sustainable

growth and innovation (Cantamessa et al., 2018).

Startups, particularly those in software development,

are uniquely challenged by the need to rapidly scale

operations while navigating resource constraints,

fragmented workflows, and evolving market

expectations (da Silva et al., 2021). These pressures

are compounded by underdeveloped team structures

and ambiguous role definitions, often hindering

performance and resilience during crucial growth

phases.

Generally, Research and Development (R&D)

functions serve as the strategic nucleus for software

startups, positioning knowledge creation and

integration at the center of capability transformation.

Yet, to unlock the full potential of R&D

contributions, startups must engage in intentional OD

practices that harmonize human, procedural, and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7110-3718

technological assets. Knowledge management (KM)

thus becomes indispensable—not merely as a tool for

operational efficiency, but as a socio-technical

framework for cultivating dynamic capabilities

(Alavi & Leidner, 2001), institutionalizing learning

(Nonaka, 2009) (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995), and

driving organizational renewal (Ren & Argote, 2011).

Effective KM methodologies enable startups to

transform tacit insights into actionable routines,

thereby enhancing collaborative engagement and

innovation throughput. Practices such as centralized

repositories, iterative feedback loops, and cross-

functional learning rituals support adaptability while

mitigating knowledge fragmentation. When

embedded within an OD strategy, KM not only

elevates execution but serves as a strategic lever for

resilience and value co-creation (Bharadwaj et al.,

2015).

This paper presents a longitudinal action research

case study exploring the strategic deployment of KM

methodologies to catalyze organizational

transformation in a scaling software startup. Guided

Badr, N. G.

Embedding Knowledge Management in R&D Capability Transformation in Software Startups.

DOI: 10.5220/0013656800004000

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2025) - Volume 2: KEOD and KMIS, pages

323-331

ISBN: 978-989-758-769-6; ISSN: 2184-3228

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

323

by continual improvement processes and grounded in

OD theory and capability lifecycle models (Adelman,

1993; Coghlan, 2019), the study demonstrates how

knowledge-led interventions, aligned with leadership

priorities and customer-centric design, can unlock

measurable improvements in delivery, innovation,

and operational alignment. Through an integrated

framework, the paper illuminates how KM functions

as the cornerstone of sustainable growth in emergent

organizational settings.

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Organizational Development in

Startups

In highly dynamic startup ecosystems, organizational

development (OD) emerges as a deliberate, theory‐

driven intervention to foster capability building,

improve process maturity, and align culture with

strategic objectives. OD originated as a planned,

long‐term effort to enhance an organization’s renewal

processes through applied behavioral science and

change‐agent facilitation (Beckhard, 1969). Over

time, OD theories have evolved to address both

stability and change, integrating concepts of learning,

resilience, and adaptability, qualities vital for young

ventures navigating uncertainty (Garengo &

Bernardi, 2007).

Startups differ from established firms in that they

operate under extreme resource constraints,

accelerated growth expectations, and evolving

business models (da Silva et al., 2021). These

conditions frequently give rise to fragmented

workflows, role ambiguity, and ad hoc decision

making, which can derail performance and inhibit

scaling (Giardino et al., 2015). Early OD efforts in

startups must therefore emphasize structural clarity,

process standardization, and team capability

development to mitigate the high failure rate observed

in the first five years of operation (Cantamessa et al.,

2018).

2.2 Essential KM Practices for OD

Within OD, continuous improvement models offer a

structured lens for integrating KM into

transformation efforts. Organizational development

practices prescribe learning cycle, for example,

prescribes iterative phases of assessment,

intervention, and monitoring, enabling startups to

validate knowledge‐led changes and calibrate

interventions in real time (Beckhard, 1969).

Similarly, action research methodology, rooted in

practitioner inquiry and collaborative problem

solving, has been successfully applied to guide

iterative OD interventions where KM artifacts, such

as dashboards and knowledge maps, serve as both

diagnostic and change‐management tools (Coghlan,

2019).

Knowledge management (KM) practices

complement OD by offering systematic practices to

capture, codify, and disseminate both tacit and

explicit knowledge, thereby institutionalizing

learning and driving dynamic capabilities (Nonaka,

2009). In nascent ventures, where knowledge resides

disproportionately with founding teams or key

technical experts, KM practices such as centralized

repositories, collaborative rituals, and feedback loops

become foundational to preserving critical insights

and preventing knowledge loss as teams expand

(Badr, 2018). KM frameworks rest on socio‐technical

foundations, recognizing that people, processes, and

technology must coalesce to enable effective

knowledge flows (Ren & Argote, 2011). For startups,

embedding KM as a socio‐technical system within

OD interventions ensures that knowledge‐centric

routines—such as design reviews, post‐mortems, and

best‐practice coding standards—are not peripheral

activities but core organizational processes that

reinforce innovation and operational consistency

(Bharadwaj et al., 2015).

2.3 KM as Dynamic Capability

A stream of research highlights the linkage between

KM capabilities and organizational performance in

technology‐driven contexts. For instance, startups that

invest in knowledge repositories and collaborative

platforms report faster product iterations and improved

cross‐functional coordination, leading to shortened

time‐to‐market and enhanced customer responsiveness

(da Silva et al., 2021). These findings underscore the

dual role of KM in driving both efficiencies through

process codification, and innovation via knowledge

recombination and serendipitous learning.

Dynamic capabilities theory further articulates

how firms sense opportunities, seize resources, and

transform operations to maintain competitive

advantage. In startup settings, the integration of KM

within OD reconstructs routines that underpin

dynamic capabilities, such as rapid prototyping,

customer‐centered iteration, and ambidextrous

exploration, thus enabling ventures to pivot

effectively and sustain value creation under volatile

market conditions (Badr, 2018).

Empirical studies of startup transformations

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

324

reveal that leadership commitment and cultural

alignment are critical precursors to KM‐driven OD

success. Founders and early executives must model

knowledge‐sharing behaviors, allocate resources for

knowledge infrastructure, and incentivize cross‐team

collaboration to overcome the inertia of informal

practices (Bharadwaj et al., 2015). Without this

sponsorship, KM initiatives risk devolving into

disconnected artifacts rather than becoming integral

elements of organizational capability. As startups

scale, the interplay between KM and OD influences

talent management and organizational architecture.

Role clarity exercises (e.g., RACI matrices) and

competency taxonomies help delineate

responsibilities, reduce overlaps, and foster

accountability (Garengo & Bernardi, 2007).

Concurrently, knowledge bases must evolve to

support branching capability lifecycles—retiring

obsolete practices, renewing critical skills, and

redeploying intellectual assets into new product

domains (Badr, 2018).

Notwithstanding these benefits, startups face

barriers in operationalizing KM within OD. Common

challenges include limited change‐management

expertise, competing short‐term priorities, and

technology adoption hurdles in resource‐constrained

environments (Okanović et al., 2020). Addressing

these obstacles requires a phased approach: initial

low‐overhead practices (e.g., peer reviews, learning

retrospectives), followed by incremental investments

in digital platforms, and culminating in governance

structures, such as change control boards and design

councils, that institutionalize knowledge flows

(Tunnicliffe et al., 2021).

3 APPROACH

Our study builds on this rich theoretical and empirical

foundation by examining how an 18-month, action‐

research–driven OD initiative leveraged integrated

KM methodologies to transform a software startup’s

R&D capability. Informed by OD principles, the

intervention prioritized leadership engagement,

customer-centric assessments, and the establishment

of a central knowledge base. By synthesizing

continuous improvement cycles with dynamic

capability theory, the case illustrates how KM can

function as both catalyst and enabler of startup

resilience, innovation, and scalable performance.

3.1 Case Study Setting

The General Manager of Company X commissioned

us to investigate and recommend measures to address

the dual demands of sales oversight and growth

acceleration at the three-year-old startup. At that

point, Company X, a software development firm

holding significant government contracts and guided

by a proactive leadership team, employed 48 full-time

staff. Its structure included a small sales force, an

operations unit responsible for logistics, project

management, and post-implementation support, and a

16-member R&D department charged with core

software development and solution delivery.

Although a human resources team handled

recruitment and compensation, organizational

development efforts were ad hoc, making sustainable

expansion feel out of reach. The GM had growing

concerns about R&D’s performance, chronic project

delays, uneven team output, blurred role definitions,

and uncertainty around deliverable statuses for key

clients. The engagement was thus designed to achieve

three strategic goals: enhance delivery capability and

precision, establish long-term revenue growth, and

strengthen the startup’s competitive position.

3.2 Engagement Summary

Following initial scoping sessions with the General

Manager and R&D Director, we structured the

engagement into three concurrent streams, each with

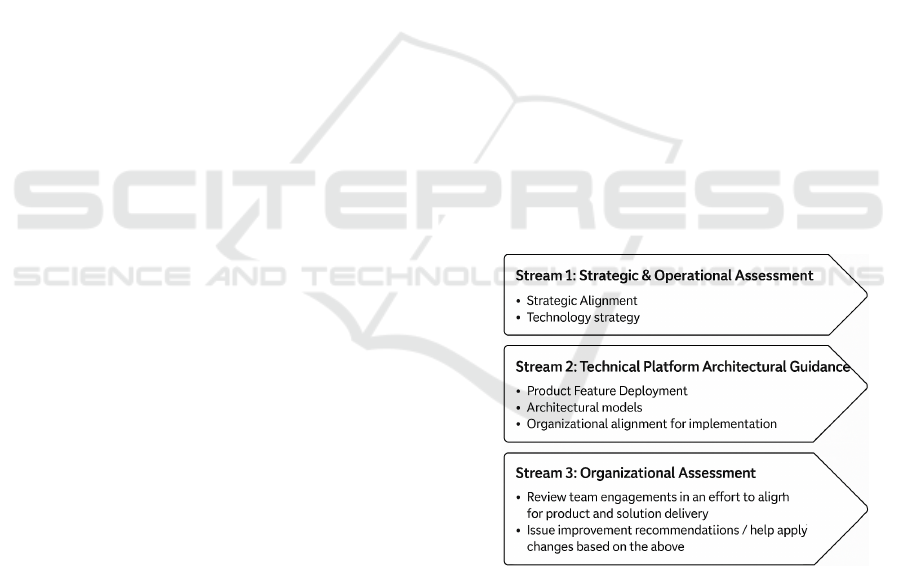

defined deliverables (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Company transformation engagement of three

parallel streams of activities.

Stream 1 – Strategic and Operational Assessment:

This stream carried out a thorough review of the

company’s strategic initiatives and operational

practices. Activities included clarifying strategic

objectives, auditing active projects, and vetting future

opportunity pipelines. We also mapped technology

strategy gaps and adjusted pre-sales proposals to better

match market demands. From these insights, we

Embedding Knowledge Management in R&D Capability Transformation in Software Startups

325

formulated targeted improvement recommendations

and implemented changes to bolster strategic

coherence and operational efficiency.

Stream 2 – Technical Platform Architectural

Guidance: Here, we evaluated the deployment

readiness of core technical components and tackled

client challenges by introducing automation and agile

practices. We developed and refined product

architecture models to align with organizational

standards and support seamless implementation.

Additionally, we delivered a modular platform

blueprint for future product launches, balancing

architectural rigor with project oversight.

Stream 3 – Organizational Assessment: Focused on

optimizing how the company delivers products and

solutions, this stream reviewed team structures and

processes against delivery objectives, then issued

prioritized recommendations for improvement. Over

an 18-month period, we tracked and evaluated the

implementation of those changes to ensure ongoing

organizational refinement and sustained performance

gains.

We conducted our longitudinal case study

centered on the organizational assessment stream

(stream 3). This paper however uses insights from

streams 1 and 2 were instrumental in framing the

broader transformation effort in framing the broader

transformation effort.

3.3 Empirical Inquiry

Once leadership endorsement was secured, the

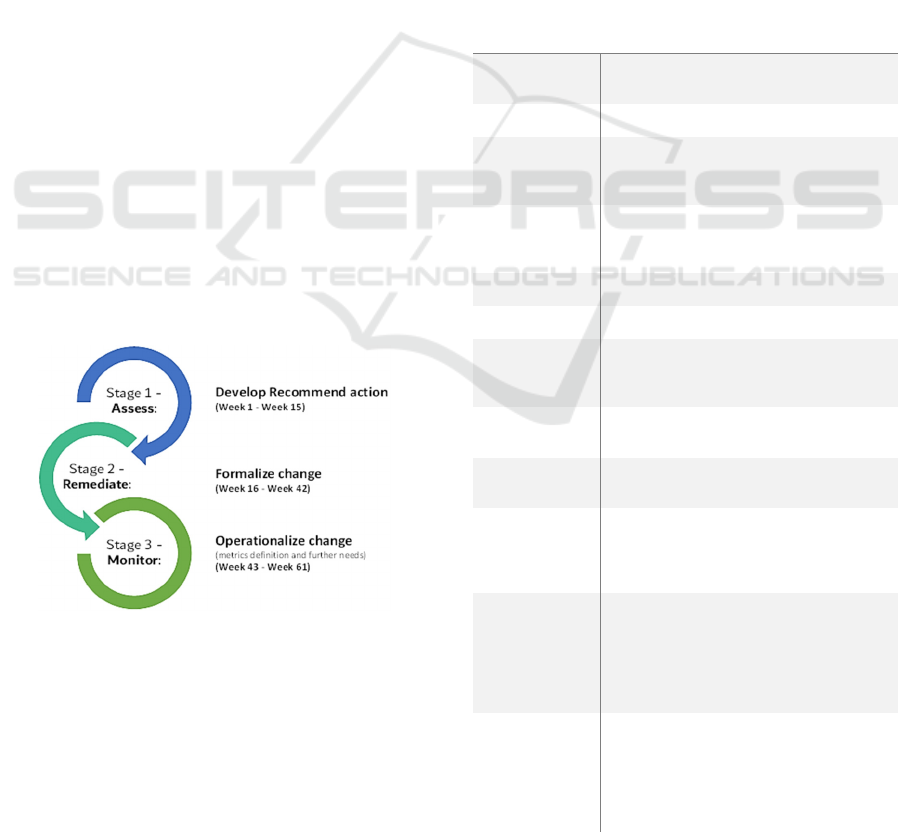

process began in three cycling stages (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Continual organization improvement ARM

process (by the author Inspired by the learning cycle of

continuous improvement (Tunnicliffe et al, 2021).

The first stage, Assess, focuses on initial

information gathering aimed at surfacing tacit

knowledge and structuring organizational insight into

actionable recommendations. This foundation guides

the second stage, Remediate, which involves the

formalization and implementation of proposed

changes derived from the assessment phase. Finally,

the Monitor (Third) stage encompasses the

operational rollout, the definition of performance

metrics, and the ongoing evaluation of effectiveness,

often triggering a return to the Assess phase for

additional data collection and refinement. The three

stages repeated iteratively as fresh data continually

refined each cycle.

At the outset, we convened with the General

Manager and the engagement sponsor to agree on our

methodology, action plan, and desired outcomes. This

kickoff meeting framed the initiative as a formal

improvement effort, fostered trust across the

organization, and created a safe space for open

dialogue (Table 1 for the action plan details).

Table 1: Action Research - Organizational development

Activities Calendar.

TIMELINE ACTIVITIES

WEEK 1

Launch Stage 1 - Assess: (Initial

Assessment)

WEEK 2 Perform initial operational assessment

WEEK 3

Review Employees Personality Tests

conducted by HR upon hire in order to realign

team structures as required.

WEEK 5

Focus on R&D organization - Conduct Team

Climate survey and 1:1 exploratory interview

and produce detailed transcripts

WEEK 9 Complete Assessment and Issue report

WEEK 10 Review report with stakeholders

WEEK 13

Communicate the report’s findings to the

teams and review the recommendations for

final feedback

WEEK 16

Launch Stage 2 - Remediate: Formalize the

changes proposed in Phase 1

WEEK 40

Complete activities for transformation (see

stage 2 activities)

WEEK 42

Review progress with stakeholders and decide

on next action. Through interviews with

middle managers and an assessment by HR

and General manager.

WEEK 43

Launch Stage 3 - Monitor: Operationalize

the changes and assess further organizational

needs. It was determined that another

extension is required to anchor the changes

and assess further organizational needs of

operating, business and functional units.

WEEK 62

Contract was terminated early due to the

completion of the duties required and the

promotion of the essential GM stakeholder to

a new position. Another contract was setup for

other objectives of strategy and corporate level

development.

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

326

3.4 Assess (Stage 1)

During Stage 1 (Assess) we partnered with the GM

and R&D director to conduct an in-depth review of

the R&D division, then planned to extend the process

to other departments by defining interdepartmental

metrics that would feed into companywide

performance evaluations.

In Week 5, we dedicated a full day to capturing

each of the 16 R&D team members’ “voice of the

customer” through individual, 30-minute,

conversational interviews. Participants were prepared

to share (1) their current tasks and priorities, (2)

projects underway, and (3) challenges they wanted

addressed. We probed deeper on recurring themes,

distilled the main improvement ideas, and validated

them with R&D leadership.

All interview transcripts were retained to

preserve the authenticity of their input. Transcripts

were retained to safeguard organizational memory

and validate insights with leadership. We triangulated

findings using transcript coding, HR personality

assessments (reviewed post-analysis to avoid bias),

and alignment checks between challenges and self-

proposed solutions, marking initial knowledge

structuring efforts.

We then conducted data analysis in three phases.

First, we coded each transcript for team

assignment, role, responsibilities, and feedback,

supplementing it with my observational notes.

Second, we reviewed employee personality

assessments from HR—conducted at hire—to

contextualize team dynamics, deliberately analyzing

our interview data first to avoid bias. Third, we

compared informants’ reported issues with their own

suggested remedies, using this alignment as a proxy

for willingness to change. Finally, we clustered

feedback into key observations and action items.

In summary (Table 2), team members cited poor

communication and visibility, particularly around

feature handoffs between PMO, R&D, and

Operations.

The assessment revealed lack in role clarity. The

R&D director had grown the team reactively, leading

to duplicated responsibilities across two product‐

focused subgroups, quality and delivery problems,

cost overruns, and elevated risk to customer

satisfaction and reputation.

Process handoff issues were reported. Process

handoff issues between PMO, R&D and Operations

were complicated with the lack of knowledge

management and documentation: there was no clear

insight regarding what features are currently being

implemented and how they work, leading to surprises

with the clients. Processes covering release

management lacked defined timelines and scope

controls, resulting in surprise deliverables and

inconsistent quality.

Table 2: Points of feedback from the data collection.

Observation Feedback from the data collection

Communication

and reporting

issues

“Total lack of communication from the

R&D team”

“Lack of visibility from upper

management regarding all activities

with the R&D team.”

Process

handoff issues

Process handoff issues between PMO,

R&D and Operations: no insight

regarding what features are currently

being implemented and how they work,

leading to surprises with the clients

Diminished

ability to deliver

Release management misalignment with

desired product objectives and customer

expectations: no time scope and

expected release date of new features.

Quality issues

“Quality assurance reviews are not

effective: serious lack of quality, due to

the fact that some features get

implemented without documentation

and in-depth analysis of the feature”.

Role clarity

Empowerment of PMO is lacking -

Ambiguous role and authority of PM

regarding all R&D functions - no

respect for deadlines, with no heads up

regarding any causes of delays

By the end of Week 9, we compiled our

assessment into a report outlining our findings and the

recommended next steps.

In Week 10, the GM convened stakeholders to

review and refine the report.

We performed an initial, SWOT analysis,

highlighting strengths (S), challenges (Weaknesses),

leadership imperatives (Opportunities), and priority

fixes (Threats). This analysis is a strategic planning

tool used to identify and evaluate an organization's

internal Strengths and Weaknesses, alongside

external Opportunities and Threats, to inform

decision-making and goal setting.

By Week 13, we presented the finalized SWOT-

driven recommendations. in a feedback session.

These high‐level delivery process proposals aim to

improve client engagement, streamline operations,

and support sustainable growth.

3.5 Formalize the Organization

(Stage 2)

Beginning in Week 16, we collaborated with middle

management and HR to translate the assessment

findings into concrete interventions.

Embedding Knowledge Management in R&D Capability Transformation in Software Startups

327

Remediation activities were organized into repeating

cycles of action and feedback, ensuring that each

iteration was built upon the last. Below is a summary

of the principal initiatives:

First, we facilitated a RACI analysis across the

organization to delineate responsibilities, eliminate

overlaps, and sharpen accountability—particularly

distinguishing between “solution development” and

“product packaging,” with the PMO orchestrating

their intersection. The RACI workshops clarified

responsibilities and surfaced latent organizational

knowledge. A RACI matrix stands for Responsible,

Accountable, Consulted, and Informed is a structured

responsibility assignment tool used in project

management to clarify roles and streamline decision-

making across tasks. It helps prevent ambiguity by

explicitly mapping each activity to stakeholders

based on their level of involvement.

Under the existing R&D director, the original

group split into Integration (requirements and

design), Customization (development and

configuration), and Delivery (QA and release

management). Each pod adopted two-week Agile

sprints to accelerate feedback and defect detection.

Agile pods accelerated knowledge loops through

biweekly retrospectives and sprint-based reviews.

Based on the RACI outcomes, a decision was

made to add two new roles to close apparent gaps.

One role was a Solutions Architect to formalize

design rigor before client handoff, and a dedicated

PMO lead to smooth engagement transitions and

reinforce project governance. In partnership with HR,

we redesigned job profiles into three tiers (e.g.,

Junior, Mid-level, Senior Developer) and accelerated

hiring for both new and backfilled roles. This tiered

structure clarified career paths and fostered cross-

disciplinary skill building.

We then established a formal communication

plan between the R&D team and the PMO, and

project managers were empowered to own scope,

timelines, and customer satisfaction throughout

solution delivery. The addition of a Solutions

Architect role institutionalized design knowledge and

ensured rigor prior to handoffs. The PMO Lead role

served as a conduit for codified best practices and

client-facing insights.

3.6 Operationalize Change (Stage 3)

From Week 43 onward, we maintained an ongoing

cycle of observation and adjustment to guide a

sustainable transformation. The latter requires more

than strategic intention, it demands robust change

governance frameworks that align institutional

structures, stakeholder engagement, and adaptive

learning processes. This is particularly critical in

dynamic environments where transformation efforts

often falter due to fragmented leadership or lack of

accountability (Rieg et al., 2021).

Hence, building on the assessment, we set out to

formalize our improvements. We convened a cross-

functional steering committee which met biweekly to

track progress and resolve roadblocks.

Two formal committees were established: a

Change Control Board to vet all internal and external

modifications, and a Design Review Committee to

ensure adherence to standards and client

requirements. These forums were structured to meet

regularly an embed learning and continuous

improvement. KM was embedded directly into

delivery processes and formalized through the Design

Review Committee and Change Control Board,

establishing knowledge as a governance asset.

We codified an end-to-end delivery process

aligned with the new team structure, supplemented by

practices of change management to support adoption.

After reviewing options, we configured Jira

(integrated into a KM platform, Confluence) to

automate workflow tracking, deliverable reporting,

and quality dashboards, thus reducing manual status

updates and enhancing visibility across stakeholders.

These mechanisms provided operational

structure and a sustainable change platform, allowing

the organization to store, share, and act on its

collective insight. Leveraging the same Atlassian

suite, we built a centralized repository for design

documents, best practices, and feedback loops,

enabling faster decision-making and safeguarding

institutional memory. The deployment of Jira and

Confluence created a living repository for design

assets, delivery templates, and continuous feedback,

bridging departmental silos and enhancing real-time

decision-making.

Throughout this phase, we addressed individual

resistance through one-on-one coaching and

customized adoption plans. As role clarity improved

and new hires completed training, team cohesion

strengthened. On Week 40 the organization was

realigned with measurable performance gains.

During Week 42 progress review, stakeholders

elected to extend the engagement briefly to

consolidate these changes into a sustainable plan for

the next product-line rollout.

Our initiative then focused on reinforcing KM

through performance metrics, coaching, and adaptive

monitoring. In collaboration with senior stakeholders,

we defined clear organizational objectives and

designed measurement methods to track progress

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

328

against both top-down and cross-functional targets.

Performance dashboards and centralized

documentation created a feedback-rich environment

that supported iterative refinement and innovation.

Team performance goals were tied to metrics

reflecting cross-team achievements, reinforcing a

culture of shared success. These metrics were

incorporated into regular performance appraisals,

ensuring continuous monitoring and improvement.

Critical information became instantly accessible

through the knowledge repository, improving

onboarding and sustaining project momentum as the

organization scaled. Embedding knowledge

management practices created real-time feedback

loops and performance dashboards that fueled

innovation, collaboration, and iterative refinement. A

centralized knowledge repository made critical

information instantly accessible and kept

documentation up to date.

By Week 60, the company had won two

substantial government contracts, requiring the

addition of roughly 70 new employees. The prior

organizational transformation strengthened the firm’s

dynamic capabilities, enabling it to absorb this rapid

growth with minimal disruption. The structured KM

tools enabled transition of knowledge to the new team

and powered their productivity.

3.7 Celebrating Success

Our intervention markedly altered the company’s

performance trajectory. Within 90 days, a previously

stalled development initiative was revived,

reputational risk was mitigated, customer confidence

was restored, and the firm recovered $2 million in lost

revenue.

On Week 62, we formally closed the action

research engagement—with a celebratory “cake

ceremony”, having met our transformation

objectives.

Although the formal OD activities concluded, the

organization continued to pursue strategic and

corporate goals under a continuous‐improvement

ethos. The organization had realized significant gains,

reviving stalled projects, recapturing revenue,

restoring stakeholder confidence, and winning major

contracts. The final celebration marked not just the

completion of a formal OD engagement, but the

emergence of a knowledge-led enterprise.

While classic OD principles provided a

framework for change, it was the intentional layering

of KM, from tacit insight capture to automated

repositories and governance integration, that

ultimately powered adaptability, alignment, and

innovation. KM transformed scattered data points

into a strategic resource, elevating both human and

organizational potential.

In the weeks that followed, the GM was

promoted to oversee the holding company,

underscoring the lasting impact of our organizational

transformation effort.

4 CONCLUSION

Our approach was built upon the foundational

elements proven to drive successful organizational

transformation (Beckhard, 1969): steadfast

leadership engagement, a clearly articulated vision,

structured change‐management processes, a

customer‐centric and adaptive culture, seamless

technology integration, ongoing improvement cycles,

with decision making grounded in data.

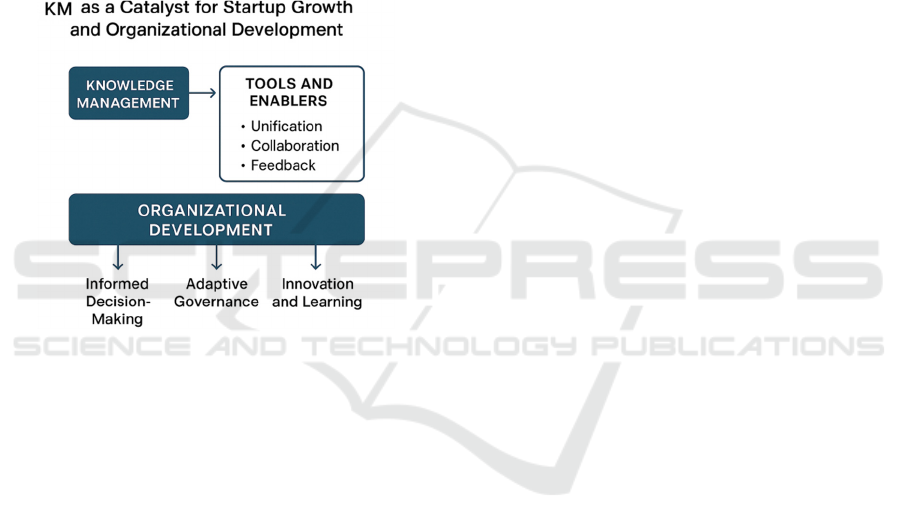

4.1 Strategic KM as Catalyst for

Startup Growth

Success in OD hinges on the startup’s ability to

translate evolving insights into scalable practices. As

demonstrated in our case study, embedding robust

KM practices and empowering the human capital

were strategic imperatives.

Startups that prioritize early investment in KM

frameworks and choose enabling tools with intention

set themselves apart. Proper KM empowers teams to

harness institutional knowledge, reinforce

accountability, and sustain adaptive capacity as scale

increases. With a unified knowledge base powering

decision-support tools, automation, and feedback

mechanisms, startups transform insight into action,

continuously.

Selecting appropriate KM tools, those aligned

with the organization’s values, workflows, and

culture, ensures that knowledge capture and retrieval

are frictionless. Whether through integrated platforms

for real-time collaboration (e.g., Notion, Confluence),

advanced tagging and semantic search engines, or

lightweight consensus and annotation layers for

distributed decision-making, these tools shape how

effectively organizations learn and adapt.

Structured KM tooling also facilitates contextual

reliability modeling—preserving not just data, but the

reasoning and lived experience behind decisions. This

depth supports post-mortem analyses, accelerates

onboarding, and reinforces psychological safety,

critical for experimentation and creative problem-

solving. When embedded into governance structures

such as Change Control Boards or steering

Embedding Knowledge Management in R&D Capability Transformation in Software Startups

329

committees, KM ensures continuity, traceability, and

shared mental models. Decision-support systems

grounded in transparent knowledge access increase

stakeholder trust and reduce cognitive load across

roles.

As scaling demands faster pivots, KM becomes

the compass guiding teams through complexity,

enabling responsible risk-taking without sacrificing

coherence. Furthermore, fostering a knowledge-

sharing culture through inclusive storytelling, active

listening, and open feedback loops amplifies the

impact of OD efforts. From humble inquiry to cross-

functional retrospectives, the social dimension of KM

unlocks innovation that is emergent, co-created, and

meaningful.

Figure 3: Strategic KM as Catalyst for Startup Growth.

4.2 Contribution and Limitations

This study advances scholarship at the intersection of

knowledge management (KM), organizational

development (OD), and startup growth by

demonstrating how KM can be operationalized as a

dynamic capability enabler in resource-constrained

R&D environments. Despite these contributions, the

study’s findings should be interpreted considering

some limitations. The dual role of practitioner-

researcher inherent in action research introduces

potential bias in data interpretation and intervention

design, despite triangulation efforts across

interviews, artifacts, and performance dashboards.

To build on this work, we propose avenues for

scholarly inquiry. Mainly, this work sets the stage for

multi-case comparative research across diverse

startup sectors can illuminate boundary conditions for

KM-embedded OD effectiveness and reveal potential

industry-specific adaptations. Additionally,

experimental or quasi-experimental designs could

isolate the impact of KM strategy elements, such as

governance forums versus repository structures,

independent of technology platforms.

Nevertheless, our paper concretizes that by

embedding strategic KM into capability

transformation, startups could accelerate internal

growth but also position themselves as learning

organizations capable of driving ecosystem-wide

change.

REFERENCES

Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action

research. Educational Action Research, 1(1), 7–24.

Alavi, M., & Leidner, D. E. (2001). Knowledge

management and knowledge management systems:

Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS

Quarterly, 107–136.

Badr, N. G. (2018). Enabling bimodal IT: Practices for

improving organizational ambidexterity for successful

innovation integration.

Beckhard, R. (1969). Organization development: Strategies

and models.

Bharadwaj, S. S., Chauhan, S., & Raman, A. (2015). Impact

of knowledge management capabilities on knowledge

management effectiveness in Indian organizations.

Vikalpa, 40(4), 421–434.

Cantamessa, M., Gatteschi, V., Perboli, G., & Rosano, M.

(2018). Startups’ roads to failure. Sustainability, 10(7),

2346.

Coghlan, D. (2019). Doing action research in your own

organization.

da Silva, L. S. C. V., Kaczam, F., de Barros Dantas, A., &

Janguia, J. M. (2021). Startups: A systematic review of

literature and future research directions. Revista de

Ciências Da Administração, 23(60), 118–133.

Garengo, P., & Bernardi, G. (2007). Organizational

capability in SMEs: Performance measurement as a key

system in supporting company development.

International Journal of Productivity and Performance

Management, 56(5/6), 518–532.

Giardino, C., Bajwa, S. S., Wang, X., & Abrahamsson, P.

(2015). Key challenges in early-stage software startups.

International Conference on Agile Software

Development, 52–63.

Nonaka, I. (2009). The knowledge-creating company. In

The economic impact of knowledge (pp. 175–187).

Routledge.

Okanović, M. Ž., Jevtić, M. V., & Stefanović, T. D. (2020).

Organizational changes in development process of

technology startups. International Conference of

Experimental and Numerical Investigations and New

Technologies, 203–219.

Ren, Y., & Argote, L. (2011). Transactive memory systems

1985–2010: An integrative framework of key

dimensions, antecedents, and consequences. Academy

of Management Annals, 5(1), 189–229.

KMIS 2025 - 17th International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Systems

330

Rieg, N. A., Gatersleben, B., & Christie, I. (2021).

Organizational Change Management for Sustainability

in Higher Education Institutions: A Systematic

Quantitative Literature Review. Sustainability, 13(13),

7299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137299

Tunnicliffe, M., Brown, N., & Shekar, A. (2021). Rapid

Learning Cycles for project-based learning. REES

AAEE 2021 Conference: Engineering Education

Research Capability Development: Engineering

Education Research Capability Development, 1094–

1103.

Embedding Knowledge Management in R&D Capability Transformation in Software Startups

331