Enhancing National Digital Identity Systems: A Framework for

Institutional and Technical Harm Prevention Inspired by Microsoft’s

Harms Modeling

Giovanni Corti

1,3 a

, Gianluca Sassetti

1,4 b

, Amir Sharif

1 c

, Roberto Carbone

1 d

and Silvio Ranise

1,2 e

1

Center for Cybersecurity, FBK, Trento, Italy

2

Department of Mathematics, University of Trento, Trento, Italy

3

Department of Defence Studies, King’s College London, London, U.K.

4

Department of Informatics, Bioengineering, Robotics and Systems Engineering, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy

Keywords:

Identity Management, Harms Modeling, Human Rights, Institutional Path Dependence.

Abstract:

The rapid adoption of National Digital Identity systems (NDIDs) across the globe underscores their role in

ensuring the human right to identity. Despite the transformation potential given by digitization, these sys-

tems introduce significant challenges, particularly concerning their safety and potential misuse. When not

adequately safeguarded, these technologies can expose individuals and populations to privacy risks as well as

violations of their rights. These risks often originate from design and institutional flaws embedded in iden-

tity management infrastructures. Existing studies on NDIDs related harms often focus narrowly on technical

design issues while neglecting the broader institutional infrastructures that enable such harms. To fill this

gap, this paper extends the collection of harms for analysis through a qualitative methodology approach of

the existing harm-related literature. Our findings suggest that 80% of NDID-related harms are the product of

suboptimal institutions and poor governance models, and that 47.5% of all impacted stakeholders are consid-

ered High Risk. By proposing a more accurate harm assessment model, this paper provides academia and the

industry with a significant contribution that allows for identifying the possibility of NDID-related harms at an

embryonic state and building the necessary infrastructure to prevent them.

1 INTRODUCTION

Civil registration and efficient Identity Management

systems (IdMs) are essential for providing individu-

als worldwide with a legal identity as well as tack-

ling the statelessness crisis, which to this day affects

1 billion people globally (Desai et al., 2018). More

studies reveal that a quarter of all children age five

and under worldwide do not possess any form of

birth registration (UNICEF, 2020), and that half of

the African population is not registered at birth (Chin-

ganya, 2019). A legal identity is considered a human

right under Article 6 of the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights (United Nations, 2021), and in light of

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8717-7512

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-2239-1913

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6290-3588

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2853-4269

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7269-9285

the previously mentioned deficiencies in guarantee-

ing this right on a global scale, the attention of gov-

ernments worldwide has turned to the capabilities of

digital IdMs in achieving greater access to identifica-

tion. The adoption of digital IdMs ranges from guar-

anteeing identification and authentication to enhanc-

ing security across technological infrastructures, but

also to simplifying the user experience in a wide range

of web applications and online services (Bertino and

Takahashi, 2010). Today, the adoption of National

Digital Identity systems (NDIDs) allows for easy ac-

cess to governmental services and applications both

online and offline with a uniform user experience. As

of 2022, at least 186 nations worldwide (out of 198)

have adopted NDIDs.

1

Adopting an NDID requires

the collection, storage, and sharing of sensible and

identifying personal data that exposes individuals–

both the direct users and the general population–to a

1

https://id4d.worldbank.org/global-dataset

Corti, G., Sassetti, G., Sharif, A., Carbone, R., Ranise and S.

Enhancing National Digital Identity Systems: A Framework for Institutional and Technical Harm Prevention Inspired by Microsoft’s Harms Modeling.

DOI: 10.5220/0013601400003979

In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Security and Cryptography (SECRYPT 2025), pages 723-728

ISBN: 978-989-758-760-3; ISSN: 2184-7711

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

723

range of potential threats (e.g., data leak) and harms

(e.g., discrimination) (Hernández, 2024). For exam-

ple, in January 2018, the world’s biggest ID database

was breached, exposing the identities and biomet-

ric information of more than 1 billion Indian citi-

zens (World Economic Forum, 2019). As a conse-

quence, NDIDs’ increased adoption is just as signifi-

cant as the controversies that they have raised (Center

for Human Rights and Global Justice (NYU), 2022).

The role of stakeholders is an important consider-

ation that is too often disregarded in the NDIDs dis-

course. Individual users, service providers, institu-

tions, and the general public are all to some extent af-

fected by NDIDs. A comprehensive Harms Modeling

strategy involving all stakeholders is essential to avoid

incomplete impact assessments. Without broad rep-

resentation, harms can extend beyond data breaches,

affecting societal institutions, reinforcing power im-

balances, and intensifying existing disparities. For

example, marginalized communities may be subject

to disproportionate surveillance or biased profiling as

a result of system design flaws or even underlying in-

stitutional biases (The Institute on Stalessness and In-

clusion, 2020).

To the best of our knowledge, the current litera-

ture presents the following gaps: (i) There is no com-

prehensive survey of NDID-related harms around the

world. (ii) Most existing studies only focus on NDID-

related harms caused by technological flaws, and lim-

ited attention is instead given to the suboptimal insti-

tutional infrastructures that enable them. (iii) There

is a lack of analysis of the causes of each harm. (iv)

There is no framework other than Microsoft’s (Mi-

crosoft Corporation, 2022) for harm assessment of

emerging technologies, and even in Microsoft’s case,

its limitations lead to underrepresentation of all im-

pacted stakeholders and inaccurate assessment of po-

tential harm.

To address these gaps, this paper extends Mi-

crosoft’s Harms Modeling (Microsoft Corporation,

2022) with a detailed qualitative analysis of the roots

of harms related to NDIDs. It introduces a more ac-

curate, NDID-focused harm measurement model that

helps anticipate potential harms and captures both di-

rect and indirect harm to General End Users. Our

research provides actionable insights for harm-aware

policymaking and assessment of NDID-enabled harm

potential in emerging technology solutions. In sum-

mary, the paper provides two main contributions:

• A survey and analysis of the harms related to

NDIDs, which also allows us to broaden the list

of affected stakeholders and analyze the root of

each harm.

• Extend Microsoft’s Harms Modeling methodol-

ogy by integrating the extended list of new harms

and stakeholders and the root of each harm, which

provides actionable insights for assessing NDID

infrastructures.

2 BACKGROUND

To make the paper self-contained, we briefly cover

the main notions underlying IdMs, NDIDs, Harms,

Threats, and Microsoft’s Harms Modeling.

2.1 Identity Management Systems

IdMs offer identification and authentication services,

provide users with a digital identity, and allow them to

access their remote resources online. IdMs may create

large and complex infrastructures in which a number

of services (RPs) rely on the digital identity issued by

identity providers (IdPs), which in turn enroll and au-

thenticate users. In this context, NDIDs represent a

special case of IdMs that is designed to access gov-

ernmental resources. In this paper, we consider both

centralized and decentralized IdMs. In decentralized

systems, IdPs are referred to as Issuers, and RPs are

called Verifiers. Given the wider audience of NDIDs

and the sensitivity of the data and resources they han-

dle, they need to ensure a high security and privacy

profile for all users. We refer to the extended set of

NDID users as General End Users, which include all

people impacted by the deployment of NDIDs, in-

cluding indirect users (for example, the children of

parents who are denied medical assistance (Center for

Human Rights and Global Justice (NYU), 2021) or

access to welfare programs (Sawhney et al., 2021) as

a result of NDID-related harms). Among General End

Users, we highlight High-Risk stakeholders: a subset

of the General End Users category considered at risk

of experiencing disproportionate harm (e.g., stateless

people) (OpenID Foundation, Elizabeth Garber and

Mark Haine (editors), 2023).

2.2 Harms Modeling and Threat

Modeling

In this paper, we focus on harms, which, despite some

similarities, differ from threats, as highlighted in Fig-

ure 1. A threat is an event with the potential to ad-

versely impact organizational operations, assets, or

individuals (Gutierrez et al., 2006). Threats occur

through attacks exploiting one or more system vulner-

abilities. Harms are events or circumstances that neg-

atively impact stakeholders directly or indirectly in-

teracting with the system that do not necessarily occur

SECRYPT 2025 - 22nd International Conference on Security and Cryptography

724

Figure 1: Intersection between threats and harms.

through an attack. Harms may result from flawed sys-

tem design and the disregard of the system’s impact

on users. A perfectly secure and privacy-preserving

system may still harm its users if it violates one or

more of their rights.

An example of a threat is a denial-of-service at-

tack during which users are denied access to services

due to malfunctions in the technical infrastructure. In-

stead, a harm would be the loss of representation as a

consequence of being unable to access NDIDs.

2.3 Microsoft’s Harms Modeling and

Foundations for Assessing Harm

Microsoft’s Harms Modeling framework (Microsoft

Corporation, 2022) has been developed to assess the

harms produced by emerging technology solutions

and consists of five steps. Step (i) focuses on examin-

ing the scope, goals, and technology employed in the

project. Step (ii) describes in detail the technology

use cases, which helps the assessor identify instances

of abuse and misuse (Strohmayer et al., 2021).

Step (iii), Consider Stakeholders, identifies all

possible stakeholders, including both those directly

and indirectly impacted by the system (we refer to this

superset of users as General end users). Identification

of all individuals is crucial for a more comprehen-

sive and inclusive harm assessment. Step (iv), Assess

potential for harm, is the central part of the analy-

sis. Harms are first identified, enumerated, and sub-

sequently evaluated in function of the system design

and the impacted stakeholders. To do this, Microsoft

suggests a qualitative and collaborative approach to

better grasp the potential extent of identified harms.

One way to identify potential harms is to brainstorm

with a selection of stakeholders. We use historical

data to develop a comprehensive selection of harms

related to NDIDs and assess their impact (see Sec-

tion 3). This approach allows for a more accurate as-

sessment of potential for harm because it provides the

parties involved in the harm potential evaluation with

an extensive list of real-world cases of harms, harm

categories, and examples that help to visualize how

harm could occur.

Additionally, during step (iv), four metrics are

produced to help evaluate the potential for harm:

severity, scale, probability, and frequency. Severity

refers to the degree of harm on impacted stakehold-

ers. Scale measures the range of the harm; this could

be a single individual, a community, the broader user

base, or even the whole population itself. Finally,

Probability measures the chances of a harm being in-

flicted on stakeholders, while frequency indicates the

quantification of the repetition of a harm. The poten-

tial of each harm is carried out as a function of these

four metrics. The reader should note that Microsoft’s

framework only differentiates harm potential in three

categories: low, medium, and high. It does not ex-

plain how the potential is carried out, nor what the

threshold is between low, medium, and high poten-

tial. The assessors are thus tasked with defining their

own potential functions.

Harm potential helps weigh the effect of different

harms on stakeholders. Step (v), Build for positive

outcomes, is dedicated to interpreting the results of

the previous steps and providing solutions for miti-

gating harm potential. In our paper, we focus on steps

(iii) and (iv) as these steps are the foundation of both

Microsoft’s Harms Modeling and our adapted NDID

Harms Modeling.

3 METHODOLOGY

We propose a qualitative methodology approach, with

which we collect NDID-related harms documented

worldwide, and we interpret them in function of our

NDID Harms Modeling, based on Microsoft’s frame-

work (Microsoft Corporation, 2022).

To gather the necessary data, we conducted a

Enhancing National Digital Identity Systems: A Framework for Institutional and Technical Harm Prevention Inspired by Microsoft’s Harms

Modeling

725

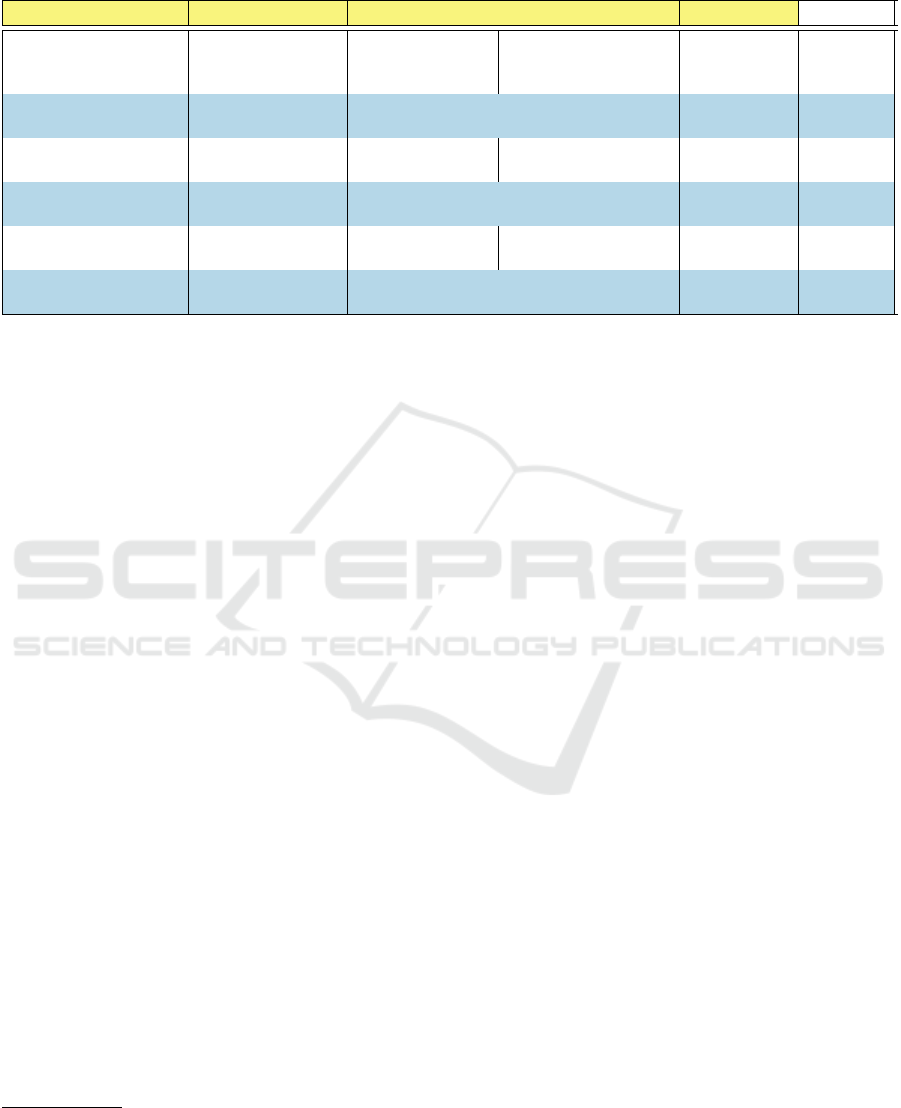

Table 1: Excerpt of harms evaluation using NDID Harms Modeling. The columns that were added are highlighted in yellow.

SH stands for stakeholders.

Harm SH (Specific) SH (General) Root (Specific) Root (General) Potential

Amplification of power in-

equality

Lower classes High Risk Abuse of power, undermin-

ing of democratic and social

processes

Institutional Pit-

fall

HIGH

Identity theft Direct users General End Users Exposure of sensitive infor-

mation

Design Flaw HIGH

Denied medical assistance Vulnerable individuals High Risk Poor governance and/or de-

ployment

Institutional Pit-

fall

HIGH

Denied monetary assis-

tance

Low-income earners High Risk Poor governance and/or de-

ployment

Institutional Pit-

fall

HIGH

Overreach and Surveil-

lance

Direct users General End Users Abuse of power Institutional Pit-

fall

HIGH

No Right to an identity Marginalized communi-

ties

High Risk Unlawful procedures Institutional Pit-

fall

HIGH

survey of harms directly and indirectly produced by

NDIDs globally. Sourcing the harms from real-world

cases allows for a more fine-grained categorization

and proof of the relevance and accuracy of each harm.

We first identified the countries that had developed

and deployed NDIDs using the data provided by the

World Privacy Forum.

2

We identified the relevant

academic and gray literature on NDID-related harms

using tailored search queries on three different search

engines (Google, DuckDuckGo, and Yandex) with

state-of-the-art adverse media search tools

3

and orga-

nized the harms collected in a final selection of harms.

The queries we used were: (digital identity OR iden-

tity management OR IdM OR NDID OR NeID OR

eID) AND (harm OR risk OR problem OR issue OR

threat OR challenge OR abuse OR misuse) AND name

of country (for each country we previously identified).

We started with 83 potentially relevant sources. After

removing duplicates and selecting sources based on

their title, abstract, and content, we were left with 71

relevant sources. From these, we analyzed the ref-

erences and collected 5 additional sources for a total

of 76 sources. A complete list of sources is available

on our companion website (Corti, 2025). These in-

clude academic papers, journalistic pieces, white pa-

pers, and other relevant grey literature, and were col-

lected during the months of July and August 2024. All

sources of harms were cross-checked to assess their

validity as well as the trustworthiness of the informa-

tion they contained.

The results of our survey were then integrated into

the Harms Modeling framework. During this step,

we extended the original framework by adding new

2

https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/2021/10/national

-ids-and-biometrics

3

https://www.no-nonsense-intel.com/adverse-media-s

earch-tool

columns to support our analysis (the reader can find

them highlighted in Table 1). We added (i) a col-

umn to include the harms found during the survey,

(ii) two columns, Stakeholders (Specific) and Stake-

holder (General), for a detailed analysis of all af-

fected stakeholders, and (iii) another two columns,

Roots of harm (Specific) and Roots of harm (Gen-

eral), to trace each harm back to a specific cause.

We populated these additional columns referencing

the relevant literature and stakeholders impacted by

the harms collected during the survey (OpenID Foun-

dation, Elizabeth Garber and Mark Haine (editors),

2023; Center for Human Rights and Global Justice

(NYU), 2022). Harms were also classified accord-

ing to whether they targeted specific subsets of stake-

holders (High Risk Stakeholders), or all stakehold-

ers indiscriminately. Finally, for the evaluation of

the roots of harm, we defined two new terms: Design

Flaw and Institutional Pitfall. The former covers all

harms produced by a technological flaw in the De-

sign of the NDIDs, including flaws caused by poor de-

sign choices as well as flaws produced by the lack of

specific technologies (e.g., Privacy-Enhancing Tech-

nology, selective disclosure, anonymous revocation,

etc.). The latter incorporates all harms produced or

enabled by flawed institutional infrastructures respon-

sible for the development and deployment of NDIDs.

Examples of institutional pitfalls include (but are not

limited to) corrupt practices, inadequate data gover-

nance legislation, abuse of authority, lack of issue-

specific agencies, and lack of critical information pro-

tection infrastructures. These additions to the original

framework make up for its shortcomings, i.e., incon-

sideration of all impacted stakeholders and missing

insights into the roots of harm, and allow for holistic,

in-depth interpretations of the collected harms.

SECRYPT 2025 - 22nd International Conference on Security and Cryptography

726

3.1 NDID Harms Modeling

Walk-Through

The end result of our Harms evaluation (Table 1) us-

ing NDID Harms Modeling is an easy-to-interpret, vi-

sual representation of different harms, along with the

root cause for said harms, the stakeholders affected by

it, and an assessment of their potential impact. Our

example evaluation shows how NDID Harms Mod-

eling can allow for an exhaustive and accurate harm

assessment of NDIDs in real-world applications. This

provides all parties involved in the development and

deployment of emerging NDIDs with a framework

that anticipates harm potential with more accuracy

and allows them to mitigate the identified risks and

develop harm-free NDIDs.

Our Harm evaluation example (Table 1), allows

for two particular values to stand out: the percentage

of High Risk Stakeholders and the percentage of De-

sign Flaws and Institutional Pitfalls. In other words,

thanks to the addition of columns Roots of harm (Spe-

cific) and Roots of harm (General) that trace each

harm back to a specific cause, a harm evaluation

through NDID Harms Modeling highlights whether

each identified harm is caused by design flaws in the

technology or by poor governance and institutional

capacity. In real-world applications, this allows for

better assessment the potential for harm infliction on

an extended pool of stakeholders at the development

stage.

To present a real-world working example of harm

evaluation through NDID Harms Modeling, we high-

light one harm from Table 1. According to our litera-

ture review, in 2022 a technical flaw in the UK’s Na-

tional Health Service (NHS) record system inadver-

tently exposed personal and sensitive patient informa-

tion which notified domestic abusers of their’ victims

medical appointments (Oppenheim, 2022). In this

case, the lack of privacy-preserving technologies and

interoperability within the complex set-up of 32,000

different computer systems in the NHS’ infrastructure

even allowed domestic abusers to track down their

victims.

In our harms evaluation example (Table 1), we

identified this as “Exposure to Domestic Abusers”

harm, which impacts victims of domestic abusers,

which in turn, are classified as High Risk stakehold-

ers. This harm is caused by the exposure of sensitive

information, which finds its roots in a Design Flaw in

the technical architecture of the system.

In real-world scenarios like this, NDID Harms

Modeling would enable all parties involved in system

development to effectively evaluate possible negative

outcomes, anticipate potential harms, and identify all

affected stakeholders. More broadly, it would help

developers detect system flaws that might put users at

risk, while also providing a potential metric of harm

that clarifies the full scope of identified risks.

This example from our research helps grasp the

importance of step (iii) Consider Stakeholders, and

(iv) Assess Potential for Harms at the foundation of

Microsoft’s Harms Modeling and our NDID Harms

Modeling. Additionally, it highlights the need for a

thorough and all-stakeholder-inclusive evaluation of

harm potential at an early stage of emerging technol-

ogy development. An extensive harm analysis such as

the one proposed in this paper through NDID Harms

Modeling would lead to a more accurate identification

of harm potential and the development of Harm-free

NDID systems. In other words, in an ideal scenario

where an exhaustive and rigorous harm assessment

that considers all impacted stakeholders is carried out,

the only harms the users could realistically be exposed

to should be limited to unforeseeable causes, such as

zero-day exploits (for Design Flaws), and a few inher-

ent limitations of bureaucratic and institutional struc-

tures (for Institutional Pitfalls).

4 RESULTS

With our survey, we identified a total of 39 harms,

which we derived from a total pool of 76 sources. Ta-

ble 1 presents an excerpt of the results; the complete

table is listed on our website (Corti, 2025). From the

analysis of the harms, we have found that:

• High-Risk Stakeholders account for an alarming

49% of all affected stakeholders, while the re-

maining 51% are General End Users.

• Stakeholders (specific) sourced from the litera-

ture include pregnant women, low-income earn-

ers, lower classes, victims, minorities, vulnerable

individuals, marginalized communities, and direct

users.

• Institutional Pitfalls make up 80% of all roots of

harm analyzed, while the remaining 20% are in-

stead traced back to Design flaws.

• Roots of harm (specific) that we have found in-

clude (but are not limited to): exclusion from wel-

fare systems, exposure of sensitive information,

poor governance and/or deployment, discrimina-

tory processes, unlawful procedures, abuse of

power, poor technical design choices, and dis-

criminatory processes, denial of human rights, bi-

ased institutions.

• Exclusion from welfare system together with Ex-

posure of sensitive information are the two most

Enhancing National Digital Identity Systems: A Framework for Institutional and Technical Harm Prevention Inspired by Microsoft’s Harms

Modeling

727

frequent Specific roots of harm.

• The category with the most sources document-

ing the harms is: Infringement on human rights,

which also includes the two most extensively re-

searched harms: Exposure of Sensible Data and

Overreach and Surveillance.

• 34 out of 39 (87%) harms analyzed are high po-

tential (potential metric greater than 35).

• 16 out of the 19 (84%) harms affecting High Risk

stakeholders are high potential.

• 55% of harms produced by technical design flaws

and 97% of harms rooted in institutional pitfalls

are high potential.

5 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, we have presented a survey of harms

related to NDIDs, which is then embedded in an

adaptation of Microsoft’s Harms Modeling frame-

work. The framework enables a user-centric evalua-

tion of the impacts of NDIDs, highlighting their con-

flict with human rights and international law. The

goal of the survey is to identify and evaluate harms.

To do so, we analyzed academic and grey literature

to investigate NDIDs-related harms across the world.

Alarmingly, our results show that 80% of NDID-

related harms are the product of suboptimal institu-

tions and poor governance models and that 47.5% of

all impacted stakeholders are considered High Risk.

In future work, we plan to involve expert evalua-

tions to validate the completeness and correctness of

our qualitative findings, and we plan to investigate

the potential of institutional path dependence theory

and increasing returns dynamics in explaining the re-

sults of this research. The idea behind this approach

is to analyze the causal, self-reinforcing relation-

ship between poor governance models and suboptimal

NDIDs, even in light of better alternatives. Addition-

ally, future work will explore possible suboptimal-

to-optimal path switch-over solutions in the name of

harm-aware NDIDs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been partially supported by a joint

laboratory between FBK and the Italian Government

Printing Office and Mint and by project SERICS

(PE00000014) under the MUR National Recovery

and Resilience Plan funded by the European Union

- NextGenerationEU.

REFERENCES

Bertino, E. and Takahashi, K. (2010). Identity Management:

Concepts, Technologies, and Systems. Artech House.

Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (NYU) (2021).

Chased away and left to die. Accessed: 2024-02-13.

Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (NYU) (2022).

Paving a digital road to hell? Available at: Report:

Digital Road to Hell.

Chinganya, C. (2019). Speech at the 5th conference of

africa ministers responsible for civil registration, ex-

pert group meeting. Available at: Civil Registration

Expert Group Meeting.

Corti, G. (2025). Complete List of NDID Harms. Available

at:NDID Harms List.

Desai, V., Diofasi, A., and Lu, J. (2018). The global identifi-

cation challenge: Who are the 1 billion people without

proof of identity? Available at: The global identifica-

tion challeng.

Gutierrez, C. M., Jeffrey, W., and FURLANI, C. M. (2006).

NIST FIPS PUB 200. Available at: NIST FIPS 200.

Hernández, M. D. (2024). Why we need tailored identity

systems for our digital world. Available at: Access-

Now Web.

Microsoft Corporation (2022). Harms Modeling Frame-

work. Available at: Harms Modeling Framework.

OpenID Foundation, Elizabeth Garber and Mark Haine (ed-

itors) (2023). Human-centric digital identity: for gov-

ernment officials. Available at: Human-Centric Digi-

tal Identity Report.

Oppenheim, M. (2022). NHS to send alerts to domestic

abuse victims. Available at: Independent UK News.

Sawhney, R. S., Chima, R. J. S., and Aggarwal, N. M.

(2021). Busting the dangerous myths of big ID pro-

grams: Cautionary lessons from India. Access Now

Publication.

Strohmayer, A., Slupska, J., Bellini, R., Coventry, L.,

Hairston, T., and Dodge, A. (2021). Trust and abus-

ability toolkit: Centering safety in human-data inter-

actions. Northumbria University.

The Institute on Stalessness and Inclusion (2020). Locked

in and locked out: the impact of digital identity sys-

tems on rohingya populations. Available at: Report:

Impact of NDIDs in Rohingya.

UNICEF (2020). Birth registration data. Available at:

UNICEF Report on Birth data.

United Nations (2021). Universal declaration of human

rights. Available at: UN declaration of Human Rights.

World Economic Forum (2019). The global risks report

2019 (14th edition). Available at: Global Risks Re-

port.

SECRYPT 2025 - 22nd International Conference on Security and Cryptography

728