Designing a Multimodal Interface for Text Simplification: A Case Study

on Deepfakes and Misinformation Mitigation

Francisco Lopes

1 a

, S

´

ılvia Ara

´

ujo

1 b

and Bruno Reynaud Sousa

2 c

1

School of Letters, Arts and Human Sciences, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

2

School of Law, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

Keywords:

Text Simplification, AI Literacy, Multimodal Learning, Graphical Abstract, Misinformation, Deepfakes.

Abstract:

The complexity of scientific literature often prevents non-experts from understanding science, limiting ac-

cess to scientific knowledge for a broader audience. This paper presents a proof-of-concept system designed

to enhance the accessibility of primary scientific literature through multimodal graphical abstracts (MGAs).

The system simplifies complex content by integrating textual simplification, visual elements, and interactive

components to support a broader range of learners. Using a case study on deepfake detection, the paper

demonstrates the system’s functionalities. Key features include automated text simplification, audio narration,

content summarization, and information visual representation. The example presented suggests the use of the

generated MGA to improve AI literacy and misinformation resilience by promoting direct engagement with

scientific content. Future work will focus on assessing the quality of text simplification and validating its

effectiveness through user studies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital literacy equips individuals with competencies

necessary to critically interact with, evaluate, and

ethically utilize digital tools. It includes the ability

to find, evaluate, utilize, share, and create informa-

tion through digital technologies (Reddy et al., 2021).

Similarly, Artificial Intelligence (AI) literacy focuses

on understanding AI systems, enabling users to criti-

cally evaluate their implications, use them effectively,

and address ethical concerns surrounding their adop-

tion (Long and Magerko, 2020; Ng et al., 2021; Allen

and Kendeou, 2023). Promoting these skills align

closely with the United Nations’ Sustainable Devel-

opment Goal (SDG) number 4 (Quality Education),

which emphasizes the importance of ensuring equi-

table and inclusive education for all, and is recognized

as a catalyst for achieving broader SDGs. As digital

and AI literacy become increasingly essential, they

also offer opportunities to narrow the gap between

technical expertise and public understanding, poten-

tially improving scientific communication.

Challenges in scientific communication present

barriers to the dissemination and understanding of

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0372-6257

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4321-4511

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0502-1305

knowledge, particularly due to the complexity of sci-

entific texts and the inaccessibility of technical lan-

guage (Borowiec, 2023). Overcoming technical and

complex language in scientific texts is a challenge

for communicating with the general public (Pruneski,

2018). The use of specialized vocabulary, complex

syntax, and jargon often alienates non-expert audi-

ences and contributes to misunderstanding and mis-

trust of science (Ivleva, 2022).

One potential approach to this challenge is text

simplification, which can reduce lexical and syntac-

tic complexity while preserving the core meaning

of scientific content, making it more accessible to

non-experts (Al-Thanyyan and Azmi, 2021). Sim-

plified texts have improved readability, making sci-

ence more understandable for individuals with low

literacy, non-native speakers, and those unfamiliar

with technical domains (Wan, 2018; Engelmann et al.,

2023). This is particularly relevant for those who

may have limited exposure to the terminology and

structure of specialized scientific texts (Engelmann

et al., 2023). Moreover, simplified scientific com-

munication enables broader public engagement with

research findings, which is essential for promoting

trust in science (Beks van Raaij et al., 2024). One

of the main challenges in simplifying scientific texts

is reducing both lexical (word-level) and syntactic

Lopes, F., Araújo, S. and Sousa, B. R.

Designing a Multimodal Interface for Text Simplification: A Case Study on Deepfakes and Misinformation Mitigation.

DOI: 10.5220/0013513100003932

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 1, pages 737-742

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

737

(sentence-level) complexity, without compromising

technical accuracy or losing essential meaning (Garuz

and Garc

´

ıa-Serrano, 2022; Ivleva, 2022).

The ongoing development of text simplification

technologies, particularly those based on generative

AI, presents significant potential for improving com-

munication between experts and non-experts (Sikka

and Mago, 2020). Recent advancements have enabled

the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) like T5,

PEGASUS, and ChatGPT to simplify complex sci-

entific content (Wan, 2018; Engelmann et al., 2023).

These models have been shown to be effective in sim-

plifying technical language across various contexts,

such as radiology reports (Doshi et al., 2023), dietary

supplement information (Tariq et al., 2023) and gov-

ernment communication (Beks van Raaij et al., 2024).

Building on these premises, this work presents a proof

of concept for a system designed to generate sim-

plified multimodal abstracts from primary literature.

The major contributions of this paper are:

• Designing a proof of concept system that simpli-

fies complex scientific content through the gener-

ation of multimodal graphical abstracts.

• Demonstrating the system’s functionality through

its application in simplifying a research paper on

deepfakes.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 re-

views related work on text simplification, multimodal

learning, and graphical abstracts. Section 3 details

the system design and implementation. Section 4

presents a case study focusing on deepfake detec-

tion, demonstrating the system’s capabilities. Section

5 discusses findings and implications. Finally, Sec-

tion 6 offers conclusions and directions for future re-

search.

2 RELATED WORK

This section reviews key concepts supporting the de-

velopment of the system, focusing on adapting pri-

mary literature, applying multimodal learning prin-

ciples, and integrating the concept of graphical ab-

stracts.

2.1 Adapting Primary Literature

Didactic transposition refers to the process of trans-

forming scientific knowledge from its original form

into a form that is suitable for teaching, ensuring it

is meaningful to learners in the classroom (Cheval-

lard and Bosch, 2020). As scientific knowledge is ini-

tially designed for use in its original context, not for

direct teaching, it must undergo transformations to fit

the goals of education (Kang and Kilpatrick, 1992).

This process involves adapting the content to ensure

it is both comprehensible and engaging, while main-

taining its integrity and core concepts. The result of

didactic transposition is the creation of learning ob-

jects, small, self-contained units of learning that en-

capsulate specific scientific knowledge in a format

that is easy for students to engage with (Chevallard

and Bosch, 2020). These objects could be textbooks,

teaching materials, online resources, or even interac-

tive models. The ability to adapt complex knowledge

into teaching-friendly formats is therefore essential

for cultivating scientific literacy.

2.2 Multimodal Learning

Multimodal learning refers to the use of multiple sen-

sory systems (e.g., visual, auditory, kinesthetic) in the

learning process, which can keep students more in-

terested and promote deeper understanding (Al-Jarf,

2024). This approach integrates various modes of

learning, such as text, images, video, audio, and

physical interaction, to create a holistic learning en-

vironment that engages learners on multiple levels

(Qushem et al., 2021). The combination of modalities

can help learners better understand complex explana-

tions and concepts by reducing cognitive load (Mayer,

2001, 2003).

Multimodal learning supports learner autonomy

by allowing students to interact with content in var-

ious ways and to select the modes of learning that

suit their preferences and needs (Al-Jarf, 2024). Mul-

timodal technologies like MOOCs, serious games,

and learning management systems employ multi-

ple modes of interaction to support diverse learn-

ing preferences and knowledge acquisition (Qushem

et al., 2021). These technologies create more inclu-

sive learning environments, allowing students to en-

gage with content in a flexible, interactive manner.

Neurodivergent learners (e.g., students with ADHD,

dyslexia) particularly benefit from multimodal learn-

ing, as it provides alternative means of engagement

and helps maintain their focus through diverse sen-

sory inputs (White, 2024).

2.3 Graphical Abstract

As scientific research becomes more specialized, tra-

ditional text-heavy abstracts often fail to engage non-

expert readers and even specialists from other fields.

Graphical abstracts (GA) provide an alternative by

offering concise, visual summaries of a study’s key

findings. These visual representations make research

EKM 2025 - 8th Special Session on Educational Knowledge Management

738

easier to understand, share, and remember, helping to

improve accessibility and engagement, allowing au-

diences to quickly grasp and retain essential informa-

tion (Lee and Yoo, 2023).

Graphical abstracts simplify complex ideas by

breaking them down into visually digestible elements,

making them accessible to both expert and non-expert

audiences. They transform dense, technical informa-

tion into easily understandable content, using images,

icons, and diagrams to represent key concepts, pro-

cesses, and results (Misiak and Kurpas, 2023). This

visual representation makes it easier for readers to un-

derstand the main ideas of a study without needing to

read through the entire paper. By creating a visually

compelling summary, researchers are more likely to

attract attention to their work, encouraging citations,

and greater engagement with their research.

2.4 Multimodal Graphical Abstract

Building on the ideas of text simplification, multi-

modal learning, and graphical abstracts, we intro-

duce the concept of the Multimodal Graphical Ab-

stract (MGA). It aims to support efforts to improve

the accessibility and comprehensibility of primary lit-

erature by combining visual elements, simplified text,

and multimodal principles into a cohesive format. A

traditional graphical abstract distills the key findings

of a research paper into a visual format. However,

for non-expert audiences, even these visual represen-

tations still pose challenges, as they are typically de-

signed with expert audiences in mind.

Combining interactive elements, dynamic visual-

izations, and simplified text creates a richer, more en-

gaging learning experience, making complex scien-

tific discourse more accessible to the general public’s

diverse learning needs. The simplified text ensures

that key concepts are communicated clearly, while the

graphical elements reinforce and expand on the text,

offering a more holistic understanding of the subject

matter. The interactive nature of the multimodal com-

ponents further encourages active learning, allowing

users to explore the content at their own pace.

Ultimately, the MGA serves as a means to democ-

ratize scientific knowledge, making it more accessi-

ble, engaging, and understandable for a wider audi-

ence.

3 SYSTEM DESIGN

The goal of this system is to automate the creation of

MGAs. The system’s main target users are individu-

als with varying levels of expertise in scientific top-

ics. Specifically, the system aims to support students

and educators who require simplified access to com-

plex academic research, as well as citizens interested

in gaining a deeper understanding of scientific con-

tent. To build the system, we conducted literature re-

views and analyzed existing graphical abstract guide-

lines and resources that focus on simplifying primary

scientific literature. We reviewed specialized journals

like Frontiers for Young Minds

1

, which focuses on

making complex science more accessible for younger

audiences. This research helped shape the system’s

goals and features, ensuring that it would meet the

needs of its target users.

The system was built using the OpenAI API for

text processing and simplification, the Narakeet API

for audio generation, and the Streamlit framework for

the user interface. Currently, in its initial version, the

system is still in the testing phase. As a proof-of-

concept prototype, only a subset of the functional re-

quirements has been implemented, with further devel-

opment planned for future versions. Non-functional

requirements, such as performance and scalability,

will also be addressed in subsequent iterations.

4 STUDY CASE: DEEPFAKES

Deepfakes refer to digital content, like images,

videos, and audio, created using AI tools that manip-

ulate reality, often producing content indistinguish-

able from authentic material (Kietzmann et al., 2020).

These technologies can be used to create fake media

that is harder to detect, posing serious risks to pri-

vacy, security, democracy, and trust (Nguyen et al.,

2019; Verdoliva, 2020). The creation and detection of

deepfakes require a sophisticated level of both AI and

media literacy. Without proper understanding, users

can become susceptible to misinformation and may

struggle to critically engage with this kind of content

(Sanchez-Acedo et al., 2024).

One of the primary barriers to addressing the chal-

lenges posed by deepfakes is the lack of AI literacy

among the general public. Simplifying and contex-

tualizing complex AI concepts can help individuals

understand how deepfakes are created, how they can

be detected, and why they are a problem in the first

place (McCosker, 2022). By breaking down the tech-

nical aspects of deep learning and AI algorithms used

to create deepfakes, it becomes possible to educate

the public in a way that makes these concepts more

accessible and meaningful (Nguyen et al., 2019). By

providing resources that demystify deepfake creation

1

https://kids.frontiersin.org/

Designing a Multimodal Interface for Text Simplification: A Case Study on Deepfakes and Misinformation Mitigation

739

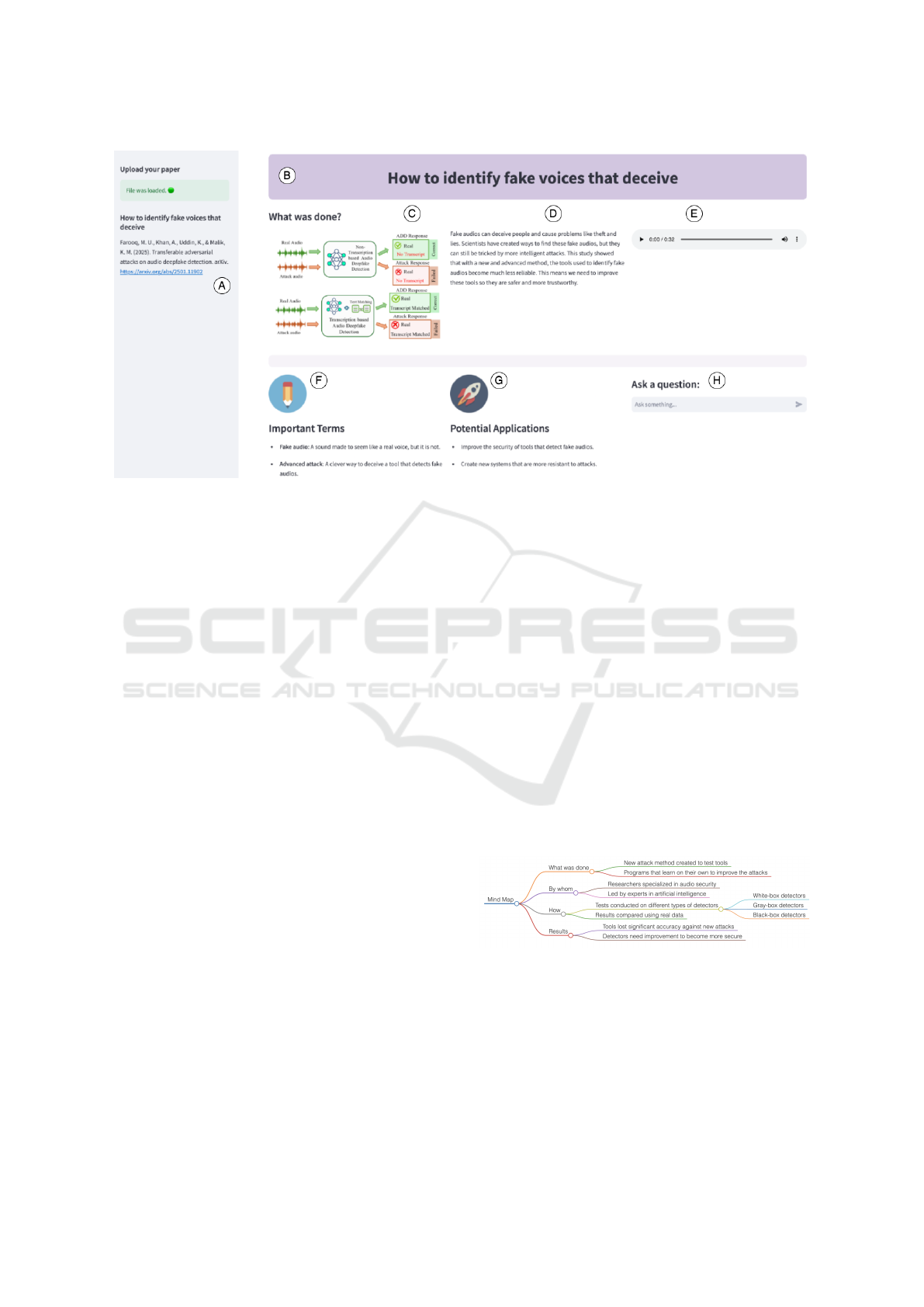

Figure 1: Screenshot of the system interface showcasing the main features (Content in Portuguese): (A) Uploaded scientific

paper reference, (B) Simplified title, (C) Extracted image from the study, (D) Simplified text summary, (E) Audio playback

of the summary, (F) Important terms glossary, (G) List of potential applications, and (H) Interactive chatbot.

and detection can help educate the public, enabling

them to identify and reject false media. It can also

enhance understanding of AI’s broader implications,

such as ethical concerns, algorithmic biases, and se-

curity threats (Verdoliva, 2020; Kian et al., 2024).

Programs designed to increase AI literacy can

equip individuals with the critical thinking skills

needed to recognize deepfake content, thereby en-

hancing societal resilience against misinformation

(Mokadem, 2023). Studies have shown that media lit-

eracy training significantly improves detection rates

for fake news, including deepfake videos (Mokadem,

2023).

For demonstration purposes, we use a study by

Farooq et al. (2025) on transferable adversarial at-

tacks to showcase the system’s capabilities. The

study investigates the robustness of audio deepfake

detection models against adversarial attacks, explor-

ing how these attacks can be transferred between dif-

ferent models.

The system interface, as shown in Figure 1, inte-

grates several features to provide users with a inter-

active experience when exploring research on deep-

fake detection. The interface begins with (A) the up-

loaded scientific paper reference, which allows users

to quickly trace the original study. The (B) simpli-

fied title offers a concise overview of the research,

while (C) displays an example of an image extracted

from the paper, illustrating the type of visual con-

tent included in the study. The system also provides

a simplified text summary (D), breaking down intri-

cate concepts into digestible information. Addition-

ally, (E) enables audio playback of the summary, of-

fering support for those who prefer auditory learning.

To support understanding of technical jargon, (F) in-

cludes a glossary of important terms relevant to deep-

fake detection. Users can also explore (G) a list of

potential applications, showcasing how the findings

can be practically implemented in various real-world

scenarios. Finally, (H) offers an interactive chatbot,

allowing users to engage directly with the content by

asking questions or seeking additional information,

thus enhancing the overall accessibility and usability

of the system.

The system also generates a mind map that sum-

marizes key aspects of the study (Figure 2). It vi-

sually organizes the research objectives, contributors,

methodology, and findings, providing a clear and con-

cise overview.

Figure 2: Mind map generated by the system, summarizing

key aspects of the study. Originally in Portuguese, trans-

lated into English for easier comprehension.

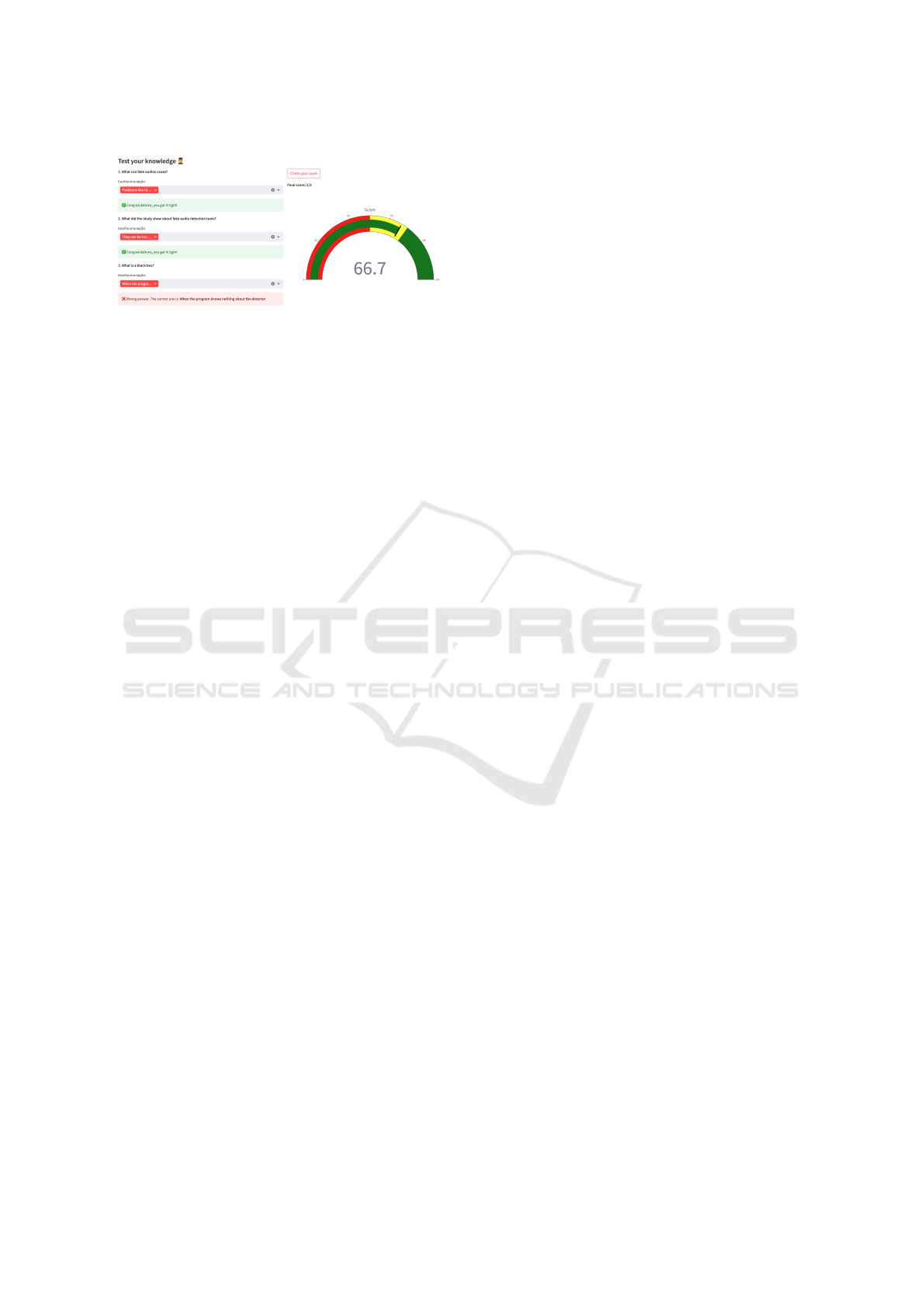

As shown in Figure 3, the system features a gami-

fied quiz designed to reinforce key concepts from the

study. By answering questions related to the research,

users can engage interactively while earning points

based on their accuracy.

EKM 2025 - 8th Special Session on Educational Knowledge Management

740

Figure 3: Screenshot of the gamified quiz feature, where

users answer questions related to the study to earn points.

The quiz features multiple-choice questions, with

correct answers highlighted in green and incorrect

ones marked in red, along with feedback on the cor-

rect response. A gauge-style score visualization pro-

vides a overview of the user’s performance.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper presents a proof-of-concept prototype

designed to make complex scientific content more

accessible, demonstrated through its application in

deepfake research. The system implements the con-

cept of multimodal graphical abstracts, combining el-

ements of text simplification, multimodal learning,

and visual elements to enhance comprehension of

complex scientific topics. We outlined the system’s

design process, and demonstrated its capabilities by

applying it to simplify a paper on deepfake detection.

The system illustrates the capacity of combining text

simplification with multimodal tools to support non-

expert communities in understanding scientific infor-

mation. This allows users to directly interact with

original research, helping them develop a more accu-

rate and trustworthy understanding of scientific con-

tent.

Future work will focus on ensuring that the sim-

plified information remains technically accurate and

does not oversimplify key concepts. This will in-

volve validating text simplification using computa-

tional metrics, along with incorporating feedback

from both experts and end-users to enhance the sys-

tem’s reliability and effectiveness.

REFERENCES

Al-Jarf, R. (2024). Multimodal teaching and learning in the

efl college classroom. Journal of English Language

Teaching and Applied Linguistics.

Al-Thanyyan, S. and Azmi, A. (2021). Automated text sim-

plification. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 54:1–

36.

Allen, L. and Kendeou, P. (2023). Ed-ai lit: An interdis-

ciplinary framework for ai literacy in education. Pol-

icy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences,

11:3–10.

Beks van Raaij, N., Kolkman, D., and Podoynitsyna, K.

(2024). Clearer governmental communication: Text

simplification with chatgpt evaluated by quantitative

and qualitative research. In Di Nunzio, G. M., Vez-

zani, F., Ermakova, L., Azarbonyad, H., and Kamps,

J., editors, Proceedings of the Workshop on DeTermIt!

Evaluating Text Difficulty in a Multilingual Context

@ LREC-COLING 2024, pages 152–178. ELRA and

ICCL.

Borowiec, B. (2023). Ten simple rules for scientists engag-

ing in science communication. PLOS Computational

Biology, 19.

Chevallard, Y. and Bosch, M. (2020). Didactic transposi-

tion in mathematics education. In Proceedings of the

2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Comput-

ing Systems, pages 214–218.

Doshi, R., Amin, K., Khosla, B., Bajaj, S., Chheang, S., and

Forman, M. (2023). Utilizing large language models

to simplify radiology reports: A comparative analy-

sis of chatgpt-3.5, chatgpt-4.0, google bard, and mi-

crosoft bing.

Engelmann, B., Haak, F., Kreutz, C., Nikzad, N., and

Schaer, P. (2023). Text simplification of scientific

texts for non-expert readers. ArXiv.

Farooq, M. U., Khan, A., Uddin, K., and Malik, K. M.

(2025). Transferable adversarial attacks on audio

deepfake detection. arXiv.

Garuz, A. and Garc

´

ıa-Serrano, A. (2022). Controllable sen-

tence simplification using transfer learning. Journal

of Computational Linguistics, pages 2818–2825.

Ivleva, N. (2022). Scientific text language code complex-

ity as a factor of communication difficulties. Bulletin

of Udmurt University. Series History and Philology,

32(3):537–545.

Kang, W. and Kilpatrick, J. (1992). Didactic transposition

in mathematics textbooks. For the Learning of Math-

ematics, 12:2–7.

Kian, L. S., Mamat, N., Abas, H., Hamiza, W., and Ali, W.

(2024). Ai integrity solutions for deepfake identifi-

cation and prevention. Open International Journal of

Informatics.

Kietzmann, J., Lee, L., McCarthy, I., and Kietzmann, T.

(2020). Deepfakes: Trick or treat? Business Horizons.

Lee, J. and Yoo, J. (2023). The current state of graphical

abstracts and how to create good graphical abstracts.

Science Editing.

Long, D. and Magerko, B. (2020). What is ai literacy?

competencies and design considerations. In Proceed-

ings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors

in Computing Systems.

Mayer, R. (2001). Multimedia Learning: The Promise of

Multimedia Learning. Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. (2003). The promise of multimedia learning: us-

ing the same instructional design methods across dif-

ferent media. Learning and Instruction, 13:125–139.

Designing a Multimodal Interface for Text Simplification: A Case Study on Deepfakes and Misinformation Mitigation

741

McCosker, A. (2022). Making sense of deepfakes: So-

cializing ai and building data literacy on github and

youtube. New Media & Society, 26:2786–2803.

Misiak, M. and Kurpas, D. (2023). In a blink of an eye:

Graphical abstracts in advances in clinical and experi-

mental medicine.

Mokadem, S. (2023). The effect of media literacy on misin-

formation and deep fake video detection. Arab Media

& Society.

Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., and Qiao, M. S.

(2021). Conceptualizing ai literacy: An exploratory

review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelli-

gence, 2.

Nguyen, T., Nguyen, Q., Nguyen, D., Nguyen, D., Huynh-

The, T., Nahavandi, S., Nguyen, T., Pham, V., and

Nguyen, C. (2019). Deep learning for deepfakes cre-

ation and detection: A survey. Comput. Vis. Image

Underst., 223.

Pruneski, J. (2018). Introducing students to the challenges

of communicating science by using a tool that em-

ploys only the 1,000 most commonly used words.

Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 19.

Qushem, U., Christopoulos, A., Oyelere, S., Ogata, H., and

Laakso, M. (2021). Multimodal technologies in preci-

sion education: Providing new opportunities or adding

more challenges? Education Sciences.

Reddy, P., Sharma, B., and Chaudhary, K. (2021). Digi-

tal literacy: A review in the south pacific. Journal of

Computing in Higher Education, 34(1):83–108.

Sanchez-Acedo, A., Carbonell-Alcocer, A., G

´

ertrudix, M.,

and Rubio-Tamayo, J. (2024). The challenges of me-

dia and information literacy in the artificial intelli-

gence ecology: Deepfakes and misinformation. Com-

munication & Society, 37(4):223–239.

Sikka, P. and Mago, V. (2020). A survey on text simplifica-

tion. ArXiv.

Tariq, R., Malik, S., Roy, M., Islam, M., Rasheed, U., Bian,

J., Zheng, K., and Zhang, R. (2023). Assessing chat-

gpt for text summarization, simplification, and extrac-

tion tasks. In 2023 IEEE 11th International Confer-

ence on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), pages 746–

749.

Verdoliva, L. (2020). Media forensics and deepfakes: An

overview. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal

Processing, 14:910–932.

Wan, X. (2018). Automatic text simplification. Computa-

tional Linguistics, 44(4):659–661.

White, J. (2024). Unlocking potential with multimodal

learning and assessment. GILE Journal of Skills De-

velopment.

EKM 2025 - 8th Special Session on Educational Knowledge Management

742