Global Bike Go: SAP-Based Mini Business Simulation Games

Robert Häusler

1a

, Malte Rathjens

1

, Erik Werner

1

, Boris Gulyak

2

and Klaus Turowski

1

1

Magdeburg Research and Competence Cluster Very Large Business Applications,

Faculty of Computer Science, Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Magdeburg, Germany

2

Research Group Non-linear Partial Differential Equations and Geometric Analysis,

Faculty of Mathematics, Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg, Magdeburg, Germany

Keywords: Business Simulation Game, IS Education, Enterprise Resource Planning, Teaching and Learning

Environment, SAP S/4HANA.

Abstract: Education Service Providers try to support lecturers by offering standardized teaching and learning

environments (TLEs). With the help of Bloom’s taxonomy, learning environments can be described and

modified by creating, adding, or adjusting learning objectives and activities. The paper shows one possible

way to adjust SAP S/4HANA TLEs for the individual learning setup. The suggestion is to use mini business

simulation games (BSGs) to enhance learners’ motivation. These games can tap into the general play instinct,

impart knowledge in a playful and practice-oriented approach, give the possibility to try things risk-free and

use the positive aspects of game elements for learning success. Exemplary, the idea and implementation of

Global Bike Go: Explore Sales as one BSG is presented. Besides the game procedure, the systemic game

architecture is elaborated to emphasize flexibility and reusability on the implementation side. Even though

game aspects in learning arrangements could enhance the learning itself, gamification is not the Holy Grail

for good learning setups. There is a need e.g. to keep the initial motivation up and to impart the knowledge,

not just seeking rewards or simply playing the game without taking any learning success out of it.

1 INTRODUCTION

Due to ubiquitous digitalization and rapid IT

progress, the demand for Enterprise Resource

Planning (ERP) systems is increasing, as they

represent a success factor for companies (Sarferaz,

2023). Consequently, trained personnel are obviously

essential. However, the number of job vacancies

increases in many countries at the same time and the

shortage of skilled workers limits the growth of

companies (Gartner, Inc.). This makes it important to

focus on education and training but the challenge is

to use suitable concepts to convey process and

application knowledge in heterogeneous ERP

education (Brehm et al., 2009; Leyh et al., 2012;

Leyh, 2017; Winkelmann and Leyh, 2010). In this

field, SAP plays a key role as one of the leading ERP

software providers.

Education Service Providers (ESPs) try to support

lecturers and trainers (Prifti et al., 2017) by offering

standardized teaching and learning environments

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2534-6070

(TLEs) consisting of a system, a model company, and

teaching materials (Häusler and Bosse, 2018).

Exemplary ESPs in the SAP domain are the SAP

University Competence Centers (UCC). They

provide curricula with theoretical and practical

materials as well as supporting tools and services

besides essential access to software, platforms, or

infrastructures. In the field of ERP teaching, the case

study method is prevailing until now (Leyh, 2017;

Leyh et al., 2012) but faces limitations in generating

motivation and providing incentives (Häusler et al.,

2021) but also in reaching sufficient levels of

cognitive learning according to Bloom’s Revised

Taxonomy (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2021).

This leads to the following research question

(RQ): How can an existing SAP-based TLE be

extended to cover additional learning objectives

and increase intrinsic motivation?

Various investigations have shown that

educational games can bridge these gaps (Fischer et

al., 2017; Hamari et al., 2016; Jacob and Teuteberg,

2017; Lukita et al., 2017) via more involving learning

868

Häusler, R., Rathjens, M., Werner, E., Gulyak, B. and Turowski, K.

Global Bike Go: SAP-Based Mini Business Simulation Games.

DOI: 10.5220/0013483600003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 2, pages 868-875

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

environments, self-effective learning options, and fun

elements. A well-known and established collection of

business simulation games (BSGs) in the field of ERP

systems is ERPsim, which has been used in education

since 2004 (Hwang, 2018; Léger, 2006; Léger et al.,

2010; Leyh, 2017; Utesch et al., 2016). But what if

existing BSGs do not fit into the highly individualized

TLEs of lectureres? ERPsim, for example, is widely

but differently used all over the world (Häusler et al.,

2024). The reasons can vary, e.g. how the educational

area is structured, and which teaching methods are

mainly used there. Regarding the games themselves,

the scope, as well as scale (number of scenarios),

complexity, or learning objectives are crucial aspects.

However, causal research should not be part of this

work, instead, it will be about additional, flexible

possibilities on the lecturers’ side.

2 BACKGROUND

The following section examines the background and

introduces the exemplary research subject. First, an

outline of BSG theory is given. Bloom’s Taxonomy,

including its two-dimensional matrix, is then briefly

introduced. It provides the basis for classifying and

describing an exemplary TLE. In this way, the actual

and target states can be compared.

The approach of this paper is to show a feasible

option to individualize, flexibalize, enrich, and extend

TLEs by adding suitable learning objectives and

activities for the respective setting with the help of

Bloom’s Taxonomy. Mini BSGs could be one option

for implementing the desired extensions. This method

is exemplary, though not the only one to take. The use

of game elements in learning scenarios is widely

examined. To date, no final, definite evaluation of the

gamification approach as a whole has been conducted

and likely never will be, due to the variety of TLEs,

content, time scope, methodologies used, the

lecturer’s role, and the different teaching and learning

types (Martí-Parreño et al., 2016; Vergara et al.,

2023; Zahedi et al., 2021). Besides the uncertainty of

the game elements’ impact, it seems quite secure that

they have a positive one on the motivation of learners,

even if gamification should be critically viewed.

2.1 Business Simulation Games

BSGs are an educational teaching method that

enhances existing learning methodologies in various

contexts (Jacob and Teuteberg, 2017). The key aspect

of BSGs lies in simulating real-world business

processes, thus allowing participants to engage with a

virtual world that goes beyond merely theoretical

learning. This simulation-based approach enables

learners to experience and act within a risk-free

environment that mirrors reality, which is conducive

to experiential and active learning (Ulrich, 2002).

BSGs comprise four fundamental elements: a

model, a simulation, roles, and a set of rules. The

model encapsulates the game’s structural framework,

temporal sequence, and overarching guidelines for

play. The simulation acts as a proxy for the system or

circumstance under examination, which is usually

strongly abstracted for ease of interaction. Within the

context of BSG, this simulation typically manifests as

a market environment with one or more competitors.

In addition to several game rounds, a BSG

comprises an introduction and evaluation (La Guardia

et al., 2014). In the introductory phase, all necessary

content-related and organizational information is

communicated, and the game rules are explained.

After the introduction, participants dive into the game

world. During individual game rounds, four phases

reoccur for players: concrete experience, reflective

observation, abstract conceptualization, and active

experimentation and testing. Concrete experiencing

describes perceiving the constantly changing system

in each round. During reflective observation,

participants question and analyze the altered

circumstances created by the simulation. Abstract

conceptualization involves forming and testing

hypotheses about the existing system and the effects

of possible actions on it (Ulrich, 2002).

Finally, the course of the game rounds is

systematically analyzed and reflected upon together

with the game leader. This aims to reinforce the

respective learning objective of the BSG among the

participants so that, ideally, the acquired skills can be

transferred to the real world. This debriefing is

essential for the successful implementation of

simulation games (Ulrich, 2002).

2.2 Bloom’s Taxonomy

“In life, objectives help us to focus our attention and

our efforts [...]. In education, objectives indicate what

we want students to learn [...]” (Anderson and

Krathwohl, 2021). Hence, it is about how to support

the learners in achieving them. Curriculum

implementers oftentimes face externally given

objectives and have to design learning environments

aligned with these objectives. Frameworks like

Bloom’s Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and

Assessing may help lecturers with this creational

process. The revised version can be represented in a

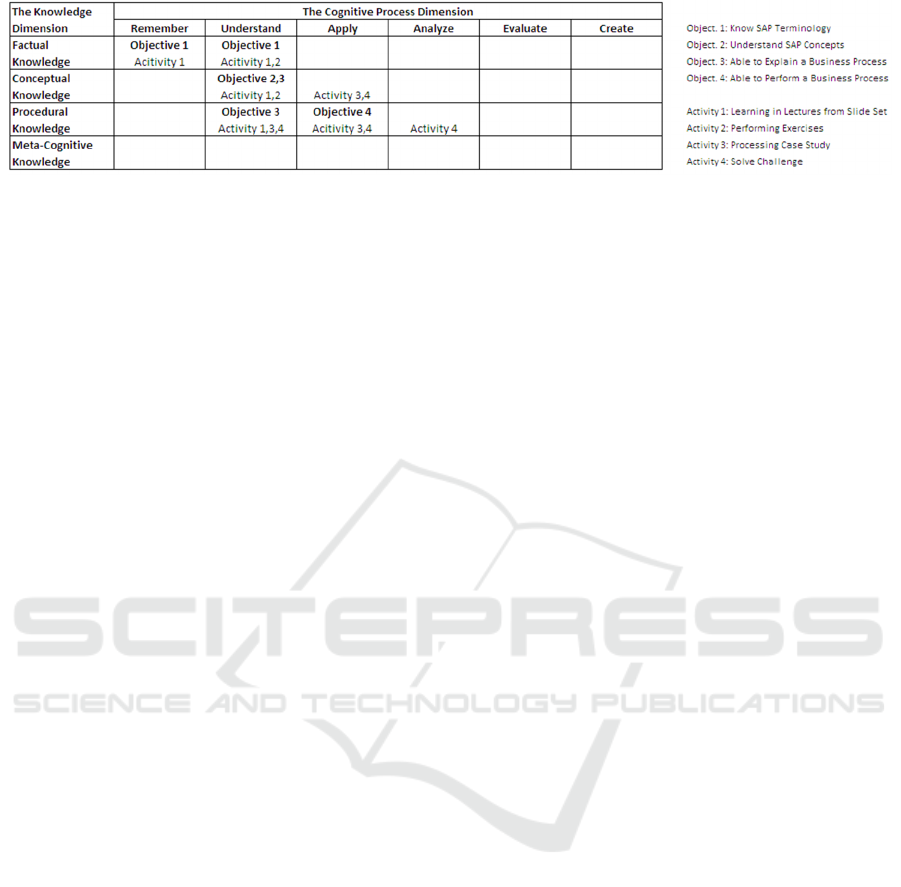

two-dimensional table as shown in Figure 1.

Global Bike Go: SAP-Based Mini Business Simulation Games

869

Figure 1: Bloom’s Taxonomy and one possible representation of an SAP S/4HANA TLE.

The first dimension represents a hierarchy of

cognitive processes that build upon one another.

Remembering involves the basic recall of facts, terms,

concepts, or procedures, whereas understanding

requires comprehension and interpretation of the

meaning. Applying entails using knowledge in new or

familiar situations to solve problems, execute tasks,

or perform actions. Analyzing consists of breaking

down complex matters into smaller components to

identify relationships, patterns, or structures.

Evaluating involves making judgments about the

quality, value, relevance, or effectiveness of

information, arguments, or outcomes. Creating

represents the highest level of cognitive processes,

which involves generating new ideas or perspectives

through synthesis, reorganization, or transformation

of existing knowledge. The knowledge dimension

complements the cognitive process dimension. It

focuses on different knowledge types that learners

develop. Learning outcomes can be categorized based

on their content. In the cells of the table which

represent intersections between both dimensions,

learning objectives can be placed (explanation

follows in the next subsection). Based on this, the

educator can design activities to match the objectives.

At best, several categories should be covered for a

sustainable learning outcome.

2.3 SAP S/4HANA TLE

To make this taxonomy more tangible, the

“Introduction to SAP S/4HANA” TLE of the SAP

UCC Magdeburg serves as experimental object. The

model company included is a bicycle manufacturer

called Global Bike. The TLE gives a comprehensive

overview of integrated business processes while

covering different taxonomy dimensions. For each of

the S/4HANA modules – like Sales and Distribution

(SD), Materials Management (MM), and Production

Planning (PP) – there are associated ready-to-use

teaching and learning materials: Slide Sets, Exercises,

Case Studies, and Challenges. They are just named

here but will be explained later on. One possible

taxonomy representation for this TLE could be the

exemplary matrix which is depicted in Figure 1. The

learning objectives listed are typical in this area but do

not correspond to any objective standard due to their

subjective nature.

As can be seen in the matrix, objective 1 is mostly

about remembering and understanding factual

knowledge, whereas objectives 2 and 3 support

understanding conceptual as well as procedural

aspects. Objective 4 would therefore be located in

applying procedural knowledge. Subsequently,

lecturers could assign activities according to the

learning objectives. Slide sets are used to provide

theoretical basic knowledge about the respective

business process (and their transition to SAP

terminology) as well as the required master and

transactional data concept. The exercises mostly give

learners an insight into the IT system and the relevant

applications, but without creating any data. In the

introductory case study, the participants perform a

well-described business process on their own in the

system. The main aim is to provide the learners with a

broad knowledge of how to interact with the system.

Mostly each case study includes a challenge where the

learners can apply the acquired knowledge in a similar

but slightly different process without precise

instructions.

The matrix is highly individualizable and

dependent on the particular curriculum. The role of the

lecturer is decisive (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2021)

and the learning arrangement is of great importance

(Kern, 2003). Especially when using third-party

materials, the objectives must be clearly defined and

the activities need to be planned on this basis. This

makes it even more important for ESPs to offer

adequate curricula, solutions, and services that match

the lecturers’ needs and support their individual TLE.

But what if they have unique requirements or identify

gaps respectively potentials in their matrix? Using

Bloom’s Taxonomy model, this results in two

possibilities. On the one hand, additional activities can

be defined with different teaching methods, but

aiming at the same learning objectives. For example,

ERPsim (“learning of ERP and business concepts

while making decisions”) could replace case studies

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

870

and challenges because of the same purpose. On the

other hand, additional learning objectives could be

defined that support or extend the original ones. If

these objectives are not achievable with the existing

activities (ESP materials or solutions), additional

activities need to be defined here as well. Both

possibilities result in the need for ESPs to increase the

variety of new, innovative solutions and possibilities

offered while meeting the demands of educators.

To enrich the taxonomy matrix for this use case,

the TLE is extended based on the gaps that the SAP

UCC Magdeburg has already identified by gathering

feedback from the user community. In addition to the

four learning objectives depicted in Figure 1, two

more could be defined to cover a broader range.

Additional learning objective 1: Get to know

the S/4HANA system (login, Fiori Launchpad,

Fiori tiles, etc.) and take the first guided steps

since ERP systems are very complex.

Additional learning objective 2: Understand

simple market mechanisms and economic

backgrounds.

To answer the first part of the RQ (how to cover

additional learning objectives), further activities

imply the design of new or adaptive solutions.

However, ESPs are facing challenges in this regard

(Häusler et al., 2024), e.g., development costs. A

flexible, scalable, and therefore cost-efficient

approach would be ideal to handle individual

community requirements. The more flexible the

solution, the easier it is to integrate into individual

TLEs. Looking at the second part of the RQ (how to

increase intrinsic motivation), many publications

demonstrated that a game-based approach can foster

motivation. By bringing both aspects together, the

individual BSG as a service approach seems

promising (Häusler et al., 2024). This is a step

towards adaptive ERP education.

3 A GAME-BASED EXTENSION

As part of the so-called Global Bike Go initiative by

the SAP UCC Magdeburg, the S/4HANA TLE

(version 4.0) was enhanced with three simple,

independent mini BSGs: (1) Explore Procurement,

(2) Explore Production, (3) Explore Sales.

They extend the problem- and scenario-based

TLE (slide sets, exercises, case studies, challenges)

with game-based aspects to expand the offerings for

lecturers. The basic ideas were to create a new

learning experience with the main focus on simplified

business processes and to use gamification elements

to improve user engagement and learning success.

In each game scenario, different companies

(between 1 and 25) compete with each other. The

participants (learners) take on business management

decisions for their assigned company. They can be

assigned individually or in groups. As determined by

the lecturer, several successive rounds are played,

with one round always corresponding to one month.

Before the game starts, the participants familiarize

themselves with the respective scenarios, and any

comprehension questions are discussed with the

lecturer. After completing the last rounds and

announcing the rankings of the participants, a

debriefing is conducted together with the lecturer. At

this point, the course of the mini-games can be

recapitulated and analyzed.

The games complement the teaching and learning

materials of the MM, PP, and SD modules and depict

parts of the business processes covered in the

S/4HANA modules. The other materials included in

the respective module can be used independently of

the games. The name part “Explore” already indicates

their low-complex and introductory character. The

games can be used as a connector between the

theoretical slide sets before taking a practical deep-

dive (case study) into a complex business process in

the S/4HANA system. The Explore games are only

intended to provide a (partial) introduction to

business processes, a basic understanding of simple

market mechanisms, an idea of the business field of

action, and to promote interest in the business

processes. However, the assumption is that especially

learners from non-specialized/other fields can be

provided with a simplified and thus facilitating access

to complex economic topics with the help of BSGs.

Additionally, one hypothesis is that learners will find

it easier to work through the case studies if they have

previously mastered the BSG because there is one

supplementary point of contact in the sense of

Bloom’s Taxonomy matrix. Furthermore, active and

playful activities as well as the simulation of real-

world processes should lead to an increase in

motivation among learners (Häusler et al., 2021;

Marinensi and Botte, 2022). Learners are offered

didactic variety through the games, which could lead

to increased motivation as well. According to

Prensky’s mini-games approach recommendation

(2008), the BSGs are highly simplified – with at most

two input parameters – and consist of easy-to-

understand scenarios and rules. Contrary to ERPsim,

they have a short duration (45 to 90 minutes in

comparison to 3h+ ERPsim) and can be used flexibly,

independently, and with different objectives. Due to

their low complexity, they can be relatively easily

Global Bike Go: SAP-Based Mini Business Simulation Games

871

extended or changed demand-driven, as already

elaborated (Häusler et al., 2024).

In general, these innovative learning tools should

enable participants to interact with S/4HANA’s

features and operations within a simulated business

environment while continually improving their

decision-making and teamwork skills. All games

were built and structured similarly. The following

exemplarily shows the idea and implementation of

Global Bike Go: Explore Sales which was developed

first. In addition to the game procedure, the systemic

game architecture is presented to emphasize

flexibility and reusability on the implementation side.

4 Global Bike Go: EXPLORE

SALES

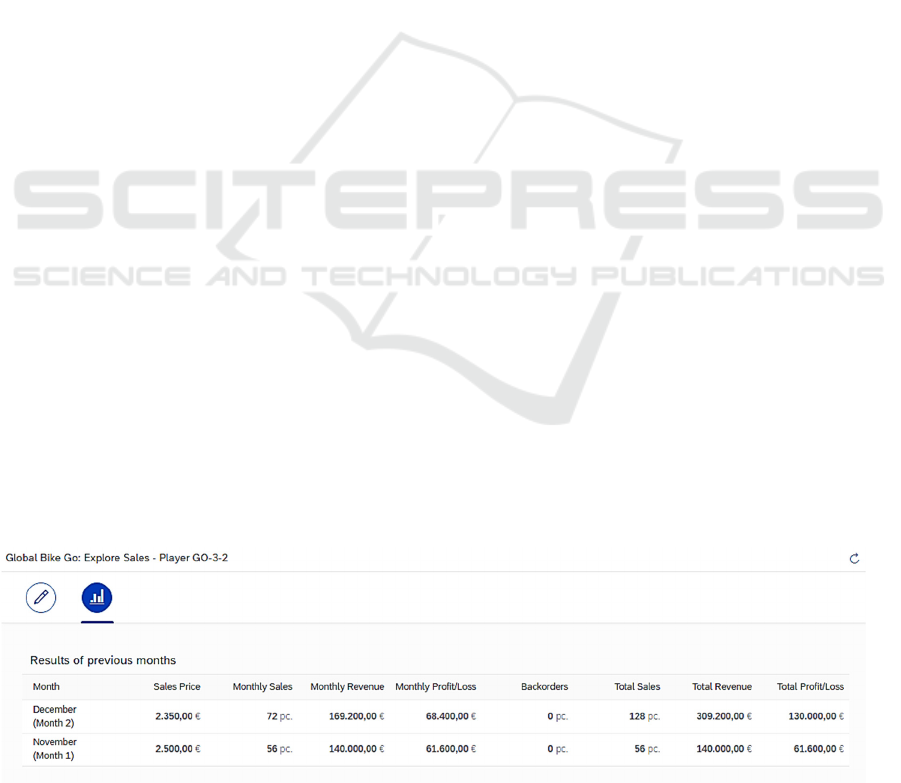

Global Bike Go: Explore Sales is a simple sales mini-

game. The ESP provides the game itself, a scenario

document, and instructions. As described in the

scenario, groups or individual players compete as

bicycle retailers for customers in a shared market. All

distributors buy the same bicycles under identical

conditions. The products and the perceived quality by

the customers are therefore the same. The only

difference between the bikes is the sales price set by

the players. By analyzing the sales results of the

current month (cf. Figure 2) and setting the sales price

for the next one, the overall goal is to maximize their

profits. After each round, stocks of all distributors are

replenished automatically, if the company has a

sufficient cash balance. As there is only one input

decision parameter, simple market mechanisms (such

as demand and supply as well as pricing) could be

better focussed on without getting lost in details.

4.1 Game Procedure

The participants make business decisions for the

company to which they are assigned in several

rounds, determined by the lecturer. Before the game

starts, the participants should familiarize themselves

with the scenario and discuss any questions with the

lecturer. After the game ends, the lecturer should

moderate a joint debriefing in which the progress of

the BSG is recapitulated and analyzed. To sum up, the

game follows one common and recommended

scheme: Briefing, Decision-making, Simulation, and

Debriefing/Evaluation (La Guardia et al., 2014).

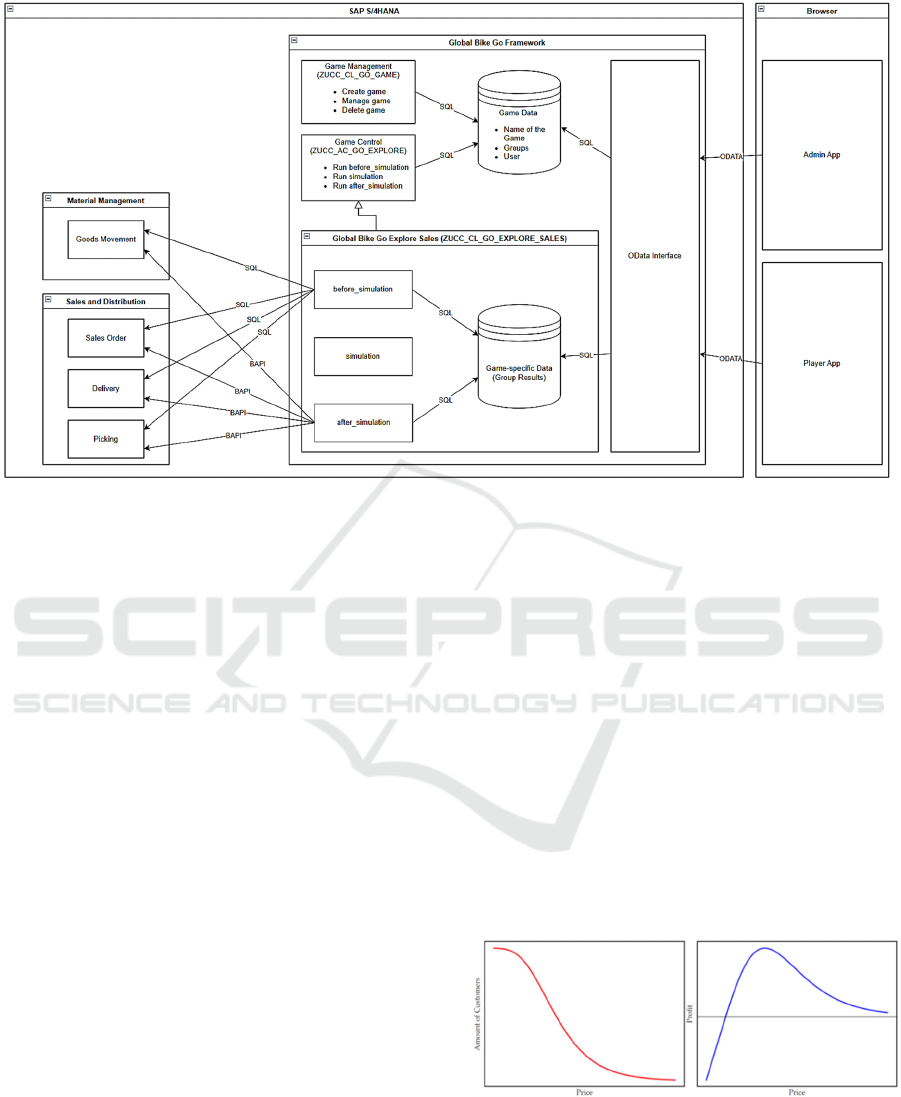

4.2 System Implementation

To get a better understanding, this section explains

the technical build. The systemic game architecture is

depicted in Figure 3.

As can be seen, the game is fully integrated into

an S/4HANA system with a browser-based user

interface. The Global Bike Go Framework which is

based on the SAP-specific programming language

ABAP and the Open Data Protocol (OData) is located

in the S/4HANA backend. It is designed in such a way

that other mini-games can use the same logic and thus

be integrated easily in the future. Besides, to interact

with the backend components, the frontend consists

of two apps – one for the player and one for the admin

– which were developed in SAP UI5 and run in the

user’s browser (accessed via SAP Fiori Launchpad).

There are three classes in the Global Bike Go

Framework: Two general ones (Game Management

and Game Control) and the exchangeable game-

specific class. The game management class is

responsible for creating, managing, and deleting the

game instances, whereas the game control class is

used to administer all necessary game-specific

metadata and actions. It generates the required data

and controls the simulation of the next round. The

Game Control is technically implemented as an

abstract class that encapsulates methods relevant to

all games. It contains the three abstract methods

before_simulation, simulation, and after_simulation.

These are executed sequentially when a round is

simulated and must be implemented by the

corresponding

game-specific class, in this case

Figure 2: Exemplary results tab from (player’s view).

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

872

Figure 3: Systemic game architecture of Global Bike Go.

Global Bike Go: Explore Sales. Both use the central

data memory Game Data via SQL, in which the meta

information of the games is stored (such as the name

of the game, information about the groups, and the

current simulation round).

The data required for the simulations is prepared

in before_simulation. This means that transactional

data is fetched from the corresponding system data

tables (e.g. stock level, number of sales), player input

values are processed, and, depending on this, further

actions are triggered in the system. In this specific

case among other things, pricing conditions are

updated and material stocks are replenished

automatically if necessary. The actual simulation

logic takes place in simulation. After_simulation

defines the result storage and the creation of

transactional data on the system side. Sales orders,

deliveries, and goods movements were created and

posted via Business Application Programming

Interfaces (BAPIs) using the standard functionalities

of the corresponding S/4HANA module (SD or MM).

All input values and game results were stored in the

Game-specific data memory – read access via SQL.

To close the loop, an OData interface is used to

deliver the data from both storages to the frontend for

all users.

To sum up, the architecture was mainly built

component-based. All existing games follow this

structure. The high level of reusability reduces future

development costs. Another advantage of the modular

structure is that individual parts can also be easily

exchanged within the games (e.g. away from profit

maximization towards other target variables).

Anyway, simulation models are controversial in

general. For some people it is too simple, some may

wish other calculations with the same variables and

others would choose a completely different approach.

The good thing about modular design, it is relatively

easy to adapt or even replace.

4.3 Simulation Model

For the first version of Explore Sales, a non-complex

market model was created. It is based on two

simplified functions: a demand function (maps

amount of sales to the selling price) and a price

difference function (maps market share to price

differences). Figure 4 shows the simplified functions.

Figure 4: Schematic representation of market model parts.

The demand is a function of the price (left side)

which is monotonically decreasing. If this function is

multiplied by the profit per piece, the graph of the

potential profit has a unique global maximum

Global Bike Go: SAP-Based Mini Business Simulation Games

873

representing the optimal selling price for the single-

player game. Upon switching to multiplayer mode,

the optimal price will shift depending on the set prices

per company (simple differential sorting and

distribution algorithm). Thirdly, seasonal effects, like

public holidays or weather conditions of different

seasons, influence the monthly demand and are also

taken into consideration. These simple curves bring

competition and make the game playable.

Surprisingly, they cover a few real-world phenomena

like dumping.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

ESPs provide technology, instructions, materials, and

service (training) if this is wanted. They support the

lecturers to make teaching more attractive, while the

lecturers continue to act as implementers. This aspect

underlines the big and relevant role the lecturers have

which needs to be filled with good didactics and

patience. With the help of Bloom’s taxonomy, they

can modify the learning environment by creating,

adding, or adjusting learning objectives and activities.

When using a BSG in their TLEs, e.g. Global Bike

Go, briefing and de-briefing are crucial; getting to

know the game rules and the setup, reflecting and

analyzing the played simulation. The so far

implemented mini BSGs are all mainly built

component-based. This way, further games can be

developed faster, easier, and more sustainable by

reusing components. Exchanges and adjustments

within the games can be adapted with low(er) effort.

Even though game aspects in learning

arrangements could enhance the learning itself,

gamification is not the Holy Grail for good learning

setups. There is the need e.g. to keep the initial

motivation up and to impart the knowledge, not just

seeking rewards or simply playing the game without

taking any learning success out of it.

A first beta use of Explore Sales in teaching led to

a small study delivering the first findings and

generated positive feedback (Häusler et al., 2023).

The study setup and practical guidance for educators

can be found there. The first small evaluation of the

use of the BSG will be extended with the help of the

SAP UCC community. This will allow more data to

be collected and evaluated to assess the embedding

and impact of BSGs. A comparative evaluation with

existing serious gaming solutions such as ERPsim at

different levels could also be target-oriented. Two

more games have already been implemented, which

should be presented in further work: Explore

Procurement and Explore Production. The

combination of the games should be used following

the value chain to assemble the whole picture; the

output of one game is the input for the following.

REFERENCES

Anderson, L.W.; Krathwohl, D.R. (2021): A taxonomy for

learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom's

taxonomy of educational objectives.

Brehm, N.; Haak, L.; Peters, D. (2009): Using FERP

Systems to Introduce Web Service-Based ERP Systems

in Higher Education. In van der Aalst, W., Mylopoulos,

J., Sadeh, N.M., Shaw, M.J., Szyperski, C.,

Abramowicz, W., Flejter, D. (Eds.): Business

Information Systems Workshops, vol. 37: Springer

Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 220–225.

Fischer, H.; Heinz, M.; Schlenker, L.; Münster, S.; Follert,

F.; Köhler, T. (2017): Die Gamifizierung der

Hochschullehre – Potenziale und Herausforderungen.

In Strahringer, S., Leyh, C. (Eds.): Gamification und

Serious Games, vol. 18: Springer Fachmedien

Wiesbaden (Edition HMD), pp. 113–125.

Gartner, Inc.: Gartner Forecasts Worldwide IT Spending to

Grow 2.4% in 2023. Available online at

https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-

releases/2023-01-18-gartner-forecasts-worldwide-it-

spending-to-grow-2-percent-in-2023.

Hamari, J.; Shernoff, D.J.; Rowe, E.; Coller, B.; Asbell-

Clarke, J.; Edwards, T. (2016): Challenging games help

students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow

and immersion in game-based learning. In Computers

in Human Behavior 54, pp. 170–179.

Häusler, R.; Bosse, S. (2018): Analysis and Modeling of

Learning Systems and Development of a Process Model

for Flexible Orchestration of Learning Environments.

In : Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik 2018.

Leuphana Universität Lüneburg, pp. 795–806.

Häusler, R.; Rathjens, M.; Staegemann, D.; Turowski, K.

(2023): Towards an Evaluation Concept for Business

Simulation Games: Preliminary Work and Piloting in

SAP ERP Teaching. In : Proceedings of the 20th

International Conference on Smart Business

Technologies. Rome, Italy: SCITEPRESS - Science

and Technology Publications, pp. 94–103.

Häusler, R.; Staegemann, D.; Turowski, K. (2024):

Individual Business Simulation Games as a Service:

Towards a Concept for Adaptive ERP Education. In :

Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on

Computer Supported Education. Angers, France:

SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications,

pp. 494–501.

Häusler, R.; Tröger, M.; Staegemann, D.; Volk, M.;

Turowski, K. (2021): Towards a Systematic

Requirements Engineering for IT System-based

Business Simulation Games. In : Proceedings of the

13th International Conference on Computer Supported

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

874

Education: SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology

Publications, pp. 386–391.

Hwang, M.I. (2018): Relationship between teamwork and

team performance: Experiences from an ERPsim

competition. In Journal of Information Systems

Education 29, pp. 157–168.

Jacob, A.; Teuteberg, F. (2017): Game-Based Learning,

Serious Games, Business Games und Gamification. In

Strahringer, S., Leyh, C. (Eds.): Gamification und

Serious Games: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden

(Edition HMD), pp. 97–112.

Kern, M. (2003): Planspiele im Internet. Wiesbaden:

Deutscher Universitätsverlag.

La Guardia, D.; Gentile, M.; Dal Grande, V.; Ottaviano, S.;

Allegra, M. (2014): A Game based Learning Model for

Entrepreneurship Education. In Procedia - Social and

Behavioral Sciences 141, pp. 195–199.

Léger, P.-M. (2006): Using a Simulation Game Approach

to Teach ERP Concepts. In Journal of Information

Systems Education 17, pp. 441–447.

Léger, P.-M.; Robert, J.; Babin, G.; Lyle, D.; Cronan, P.;

Charland, P. (2010): ERP Simulation Game: A

Distribution Game to Teach the Value of Integrated

Systems. In developments in business simulation and

experiential learning 37.

Leyh, C. (2017): Serious Games in der Hochschullehre: Ein

Planspiel basierend auf SAP ERP. In Strahringer, S.,

Leyh, C. (Eds.): Gamification und Serious Games:

Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden (Edition HMD),

pp. 151–166.

Leyh, C.; Strahringer, S.; Winkelmann, A. (2012): Towards

Diversity in ERP Education – The Example of an ERP

Curriculum. In Møller, C., Chaudhry, S. (Eds.): Re-

conceptualizing Enterprise Information Systems, vol.

105: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (Lecture Notes in

Business Information Processing), pp. 182–200.

Lukita, H.; Sujana, Y.; Budiyanto, C. (2017): Can

Interactive Learning Improve Learning Experience? A

Systematic Review of the Literature. In : Proceedings of

the International Conference on Teacher Training and

Education 2017 (ICTTE 2017). Surakarta, Indonesia:

Atlantis Press.

Marinensi, G.; Botte, B. (2022): Fostering Motivation to

Learn Through Gamification. In Bernardes, O.T.F.,

Amorim, V., Moreira, A.C. (Eds.): Handbook of

research on the influence and effectiveness of

gamification in education: Information Science

Reference (Advances in game-based learning book

series), pp. 618–635.

Martí-Parreño, J.; Seguí-Mas, D.; Seguí-Mas, E. (2016):

Teachers’ Attitude towards and Actual Use of

Gamification. In Procedia - Social and Behavioral

Sciences 228, pp. 682–688.

Prensky, M. (2008): Students as designers and creators of

educational computer games: Who else? In British

Journal of Educational Technology 39 (6), pp. 1004–

1019.

Prifti, L.; Knigge, M.; Löffler, A.; Hecht, S.; Krcmar, H.

(2017): Emerging Business Models in Education

Provisioning: A Case Study on Providing Learning

Support as Education-as-a-Service. In Int. J. Eng. Ped.

7 (3), p. 92.

Sarferaz, S. (2023): Herausforderungen und Merkmale von

ERP-Systemen. In Sarferaz, S. (Ed.): ERP-Software:

Funktionalität und Konzepte: Springer Fachmedien

Wiesbaden, pp. 3–16.

Ulrich, M. (2002): Sind Planspiele langwierig und

kompliziert? Eine Abhandlung über die

Planspielmethodik und die Ausbildung von Planspiel-

Fachleuten. In Blötz, U. (Ed.): Planspiele in der

beruflichen Bildung. 2., überarb. Aufl.: Bertelsmann.

Utesch, M.; Heininger, R.; Krcmar, H. (2016):

Strengthening study skills by using ERPsim as a new

tool within the Pupils' academy of serious gaming. In :

2016 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference

(EDUCON). Abu Dhabi: IEEE, pp. 592–601.

Vergara, D.; Gómez-Vallecillo, A.I.; Fernández-Arias, P.;

Antón-Sancho, Á. (2023): Gamification and Player

Profiles in Higher Education Professors. In

International Journal of Game-Based Learning 13 (1),

pp. 1–16.

Winkelmann, A.; Leyh, C. (2010): Teaching ERP systems:

A multi-perspective view on the ERP system market. In

Journal of Information Systems Education 21 (2),

pp. 233–240.

Zahedi, L.; Batten, J.; Ross, M.; Potvin, G.; Damas, S.;

Clarke, P.; Davis, D. (2021): Gamification in

education: a mixed-methods study of gender on

computer science students’ academic performance and

identity development. In J Comput High Educ 33 (2),

pp. 441–474.

Global Bike Go: SAP-Based Mini Business Simulation Games

875