Sharing and Accessing Autobiographical Memories Tied with Media

Francisco Ludovico and Teresa Chambel

a

LASIGE, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal

Keywords: Autobiographical and Collective Memories, Movies, Music, Personal Journal, Family Ties, Serendipity.

Abstract: Autobiographical Memory is a vital cognitive tool, as it plays a crucial role in identity formation, helping

individuals establish a sense of self and continuity across time; and it contributes to social bonding by enabling

the sharing of personal narratives. In turn, movies, music, and other media types are always present in our

lives due to being among the most relevant and emotional forms of entertainment and education. So much so

that we can easily make connections between media and memorable moments and places in our lives,

supporting autobiographical memory; and these important remembrances tend to be somehow shared with

other people, like family and close friends. With that in mind, we present a user survey carried out to learn

about user habits, preferences, and perceived needs in this context; an interactive web application being

designed and developed to allow users to register, navigate, and share their memories associated with media,

with spatio-temporal and emotional perspectives, aiming to support and strengthen sense of self and social

bonding even across generations; and a preliminary user evaluation with encouraging results.

1 INTRODUCTION

Media, in its many forms, has always had a predomi-

nant role in our lives and can serve different purposes.

Movies, songs, and TV shows are not just a form of

entertainment; as with any other art form, they allow

us to relate with them by expressing emotions and

experiences similar, in some ways, to the ones we

have lived throughout our lives (Kubrak, 2020).

Music, in particular, quite present in movies as well,

can be a strong cue for autobiographical memories,

accessible and relatively stable throughout adulthood;

being effective for achieving motivation, by favoring

positive emotional memory experiences, in particular

in older adults, also quite relevant in healthy aging

(Jakubowski et al., 2021).

As such, we can, in a straightforward manner,

make bridges and connect moments of our lives, like

important milestones and more personal remembran-

ces (for instance, trips abroad, or the first time we

have been to a place that is near and dear to us) with

movies and songs. These connections allow us to

build a richer and more complete autobiographical

memory since they are based on moments, places, and

the emotions that certain forms of media make us feel

(Holland and Kensinger, 2010). Sometimes, we also

like to share and talk about these key memories with

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0306-3352

people that surround us. Usually, these are family

members or some of our closest friends, who find

enjoyment in knowing these often-shared memories,

and sometimes they are even able to feel some of the

feelings that those important moments sparked in us.

This practice can have positive implications,

strengthening relationships with family members, and

even in our mental health (Elias and Brown, 2022).

Therefore, it is important to find a way to join

media with personal and collective memories and to

share them with people that are relevant to us,

possibly improving or nurturing relationships, and

allowing the discovery of media content that may be

found significant. Even social networks and social

media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, or

WhatsApp, respectively, allow us to share media

content that may make us remember important times

in our lives in a variety of different ways; but they

have a different purpose. While these ways of sharing

media content have become a sort of standard in our

current digital society, none of them fully explore the

articulation between personal memories, the media,

and the emotional impacts that these can have, along

time and space.

In this paper, we present a user survey conducted

to learn about how people relate to media; how often

and how they write about, keep, and share important

674

Ludovico, F. and Chambel, T.

Sharing and Accessing Autobiographical Memories Tied with Media.

DOI: 10.5220/0013370600003912

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 20th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2025) - Volume 1: GRAPP, HUCAPP

and IVAPP, pages 674-681

ISBN: 978-989-758-728-3; ISSN: 2184-4321

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

moments in their lives; how they represent the

passage of time; and their previous experience and

expectations concerning applications to store and

share autobiographical memories. Based on these

results and a review of the background in the area, we

propose and present As Ties Go By an interactive web

application being designed and developed to let users

register, navigate, and share with family members and

friends some of their most important memories,

especially those related with movies and music, and

be notified in contextualized settings in time and

space, promoting the discovery of new media content

by serendipity. Then, we present a user evaluation to

assess the usability, usefulness, and overall quality of

the user experience with the application, with

encouraging results; and conclude with final

reflections and perspectives for future work.

2 BACKGROUND

This section presents an overview of the most signifi-

cant concepts and previous research and applications

relevant to our work.

2.1

Context

Autobiographical Memory: At its core, it involves

retaining and retrieving specific events, emotions,

and contextual details tied to personal experiences

(Byrne, 2017). This multidimensional construct

comprises: episodic memory, capturing the ”what,”

”where,” and ”when” of events; and semantic

memory, providing the broader knowledge

framework that contextualizes these experiences

within one’s life story. Moreover, autobiographical

memory contributes to social bonding by enabling the

sharing of personal narratives. Through storytelling,

individuals strengthen social connections, foster

empathy, and deepen interpersonal relationships

(Bietti, 2010). The shared reminiscence of past events

creates a communal reservoir of experiences,

reinforcing the fabric of family and friendship bonds.

Collective Memory: This type of memory

represents the shared recollections and interpretations

of historical events within a community, forming a

collective narrative that transcends individual

perspectives. It emerges through the collective

processes of encoding, storage, and retrieval of

information within a community. Collective memory

is shaped by cultural, social, and historical contexts,

encompassing events, traditions, and cultural artifacts

that become part of the group’s identity (Coser,

1992). One of the inherent strengths of collective

memory lies in its ability to reinforce group identity

and cohesion. By weaving a shared narrative,

community members establish a sense of continuity,

belonging, and shared values (Harris et al., 2008).

Personal Computing: The advent of personal

computing has transformed the way individuals

interact with information, media, and each other. It

encompasses the use of individualized computational

devices, such as personal computers, smartphones,

and tablets, which have become integral components

of modern daily life. These devices empower users to

access, create, and share digital content, fostering a

new era of connectivity and personal expression

(Denby et al., 2016). In the context of memory-

sharing applications, personal computing can serve as

the foundational framework for facilitating the

seamless exchange of movies and music among

family members and close friends. The ubiquity of

personal devices opened doors to the possibility of a

digital landscape where individuals can curate and

share multimedia content that resonates with specific

events and paths of their lives (Van Dijck, 2007).

Emotional Models: Emotions significantly

influence human experiences, shaping thoughts,

actions, and wellbeing (Chambel et al., 2011). Movies

and music evoke complex emotional responses

(Hanich et al., 2014), with even sad or unsettling

content often leading to positive experiences through

”passive engagement.” This unique dynamic fosters a

deeper connection between audiences and the media,

highlighting the value of understanding emotional

models. Two major approaches to emotions rely on

dimensional and categorical models. Russell’s Model

stands out in the dimensional approach; and Ekman’s

as a Categorical Model based on universally

recognized facial expressions. Plutchik’s model

combines aspects of both dimensional an categorical

perspectives, organizing emotions in opposing pairs,

with assigned colors, around a wheel. For more

details, see e.g. (Caldeira et al., 2023).

2.2

Related Work

Media platforms allow users to explore and gather in-

formation about a wide array of media content. One

of the most popular is IMDb(.com), allowing users to

search for movies and TV shows based on several

properties, and to create media lists, save, share, rank

and comment, in reviews, these movies or TV shows;

whereas, Netflix and Spotify allow to access the

actual movies and music content. Within a research

project and with a focus both on music and movies,

As Music Goes By (Moreira and Chambel, 2019;

Serra et al., 2020) helps users discover, compare, and

Sharing and Accessing Autobiographical Memories Tied with Media

675

watch music and movies through music versions,

musicians, movie soundtracks, and movie quotes,

along time and with an emotional flavor. But they are

not focused on keeping and sharing memories.

In personal information systems and social media,

Facebook(.com) emerged as one of the first social

networks to remind its users of a post’s anniversary, as

a memory they can relive, repost, and share. Even the

posts are published in a sequence, as a timeline, in

individual accounts or groups. But they are not

specifically memories or associated with media, and

there are no visualizations and filtering in time, space,

nor based on emotions, even though it supports

reactions based on emojis and mood. In terms of

memories, more recently, some mobile phones and

tablets automatically highlight a selection of photos,

and generate memories in videos, adding a musical

background, to recall and share, as compilations of

photos and videos around common perspectives, like

proximity in location, or date, or activity (like dining,

or at the beach), etc., even suggesting a title. But these

are highlights and summaries based on photos and

videos, potentially ephemeral and isolated, not in an

integrated memory timeline, not in groups, and without

an emotional dimension. Apps like WhatsApp or

Messenger allow groups and sharing of messages with

media; but the focus is on communication, not on

memory building or sharing, non on viewing, filtering

of searching individual and group storylines other than

text search and image/msgs browsing, nor notifying

about relevant events regarding these memories.

On the other hand, Family Stories (Bentley et al.,

2011) emerged as a noteworthy creation of research to

promote intergenerational communication through

location-based asynchronous video communication.

Its users, family members in this case, capture brief

video stories encapsulating cherished memories and

engaging narratives, with properties like when and

where the memory happened. This allows to notify the

family members family, when they are close to the

place where the memory told in the video happened. In

another context, personalized video storytelling

techniques were adopted to design an interactive

weather forecast, where: family interaction supported

social reflection on the data, and connecting data with

memories was a compelling way to foster engagement

with the data presented and to support retelling the data

stories. In particular, episodic memories form a

compelling narrative device to encourage reflection,

and, linked with the data, they can be a medium to

share personal or social experiences (Van Den Bosch

et al., 2022).

EmoJar (Chambel and Carvalho, 2020) is based

on keeping and reliving memories associated with

media, with a strong focus on positive emotional

impact. Adopting the Happiness Jar metaphor, users

save in a digital jar media content represented by

“colored papers” as circles (with the color of the

dominant emotion) after having commented the semi-

automatically detected emotional impact of the

media; and then pull one out at random, when feeling

down or wanting to be reminded of good memories.

It has a personal perspective and allows one to view

and filter the jar, even search and filter by time, but it

does not represent them along time, nor space.

And “Nothing is more fundamental to a biography

than time” (Larsen et al., 1996), although viewing

information over time can be a challenge. In previous

work, we addressed multimodal search and visualiza-

tion of movies over time (Caldeira et al., 2023) with

recent extensions to As Music Goes By (Moreira and

Chambel, 2019). It explored methods that take into

account how emotional information evolves as a

movie unfolds, and enables users to query movies

based on dominant emotions, percentage of different

emotions, emojis, and emotional trajectories along

time, inside the movies; now we are focusing on the

time when the memories happened, along the years.

3 USER SURVEY

Before designing and developing the application, we

conducted a user survey to learn about: 1) how people

relate to media, in terms of their habits, attitudes,

awareness, and preferences; 2) how often and how

people write about, keep, and share important

moments that happened in their lives; 3) the different

ways that people have to represent the passage of

time; and 4) their previous experience and expecta-

tions concerning applications that allow them to store

and share their memories, connected or not to media.

Method: The survey was made available and

advertised on social media and work and family

contexts, to reach a wide range of people, in terms of

background, age, and interest in digital platforms. It

was carried out as: an online questionnaire, for wider

participation; and some interviews, based on the same

questions, in an attempt to get more complete and

insightful answers. It had a total of five sections,

mostly relying on closed questions, with the

opportunity to choose ”other” options and provide

additional comments.

Results: We present a summary of the results

gathered from the first 45 participants in the

questionnaire and 8 in interviews, focusing mainly on

the aspects that more closely inform our work.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

676

Section 1: Demographic information: Participants

aged 13-64 (M:28), 62.3% Fem, all from our country

(Portugal); 26.4% completed high school, 5.7% did

not, 7.6% had a professional course, 43.4% BSc, 17%

MSc. Participants work or study in fields that range

from informatics (20.8%) to health (11.3%),

psychology (11.3%), and education (9.4%), along

with others less frequent, in areas like finance,

economics, law, sociology, arts, and math.

Section 2: Accessing and sharing media content:

most common were communication platforms (like

WhatsApp or Messenger), followed by social

networks, video, and music streaming services, then

”others” (like videogames, museums, and movie the-

atres). Their motivation to use media: more often to

feel more relaxed, then to share with family and

friends, to feel more motivated, and to help them go

through hard times. Media content shared more often

with family and friends: music, followed by movies

and TV shows, photos, and videos.

Section 3: Memory register and sharing: 28%

quite often, 25% occasionally, and 47% rarely or

never, write about and register their memories;

whereas 55% quite often, 29% occasionally, and 16%

rarely or never, share important memories with fam-

ily or friends. To keep and share memories, they use

photos (88.2%), videos (66.7%), conversations (58.9

%), digital writing (19.6%), and personal journals

(11.8%). The importance of keeping and sharing

memories with family and friends was considered

high (5-1): very important (5) 52.8% | 26.4% | 15.1%

| 5.7% | 0% (1) not important. They associate media

with important memories: very often (28.3%), often

(41.5%), and reasonably often (24.5%). In the

interviews, they mentioned specific memories, like:

”going to the fountain in Barcelona where Shakira

recorded one of her video clips”, ”going to Disney in

Paris”, and ”a Fast and Furious movie recorded near

my father’s birthplace”.

Section 4: Time Perception: ways of visualizing

time: based on events that happened along time

(66%), in the form of a timeline (35.8%), cyclic

(17%), and divided into chapters (1.9%). In the in-

terviews, they were also asked to recall the year 2016

(when our country won the Euro football champion-

ship, and most participants mentioned it) and to think

about the last and next years, to help achieve a clearer

awareness about how they perceive and represent

time in their minds; as in the questionnaires, with a

prevalence of the role of the main events that

happened or are expected to happen in the future

coming to their minds. Big events’ impact on Time

perception: they are like milestones and help have a

better perception of time (80.8%), it makes time go

faster (13.5%), go slower (3.8%), or have no impact

(1.9%). Effect of digital technology, like social

networks, etc., on time perception: they agreed that it

makes time passage seem faster (76.9%), has no such

effect (15.4%), or depends on the situation.

Section 5: Interest in platforms that connect

memories to media: Very Interested, VI:(20.8%), and

Interested, I:(71.6%). Interest in hypothetical features

of a platform that connects memories to media: 1)

saving memories with media and time visualization in

a private journal VI:(47.2%); I:(35.8%); and 2) sha-

ring memories with media with time visualization in

a shared space: VI:(30.2%); I:(43.4%); 3) identifying

songs playing to access and create related memories:

VI:(29.4%); I:(45.1%); 4) having emotional informa-

tion on the memories they saved and shared: VI:(29.4

%); I:(31,4%); 5) filtering memories by author in

groups: VI:(32.1%); I:(37.7%); and 6) notifications

about memories based on time they happened, or

place close to their current location, etc.: VI:(32.1%);

I:(43.4%). On the last open question, about feature

suggestions, the most relevant answers include: ”ha-

ving our memories show up in a map visualization”;

“configure to not be reminded about some memories,

e.g. sad events”; and “be notified when someone from

our family adds a memory with us”.

4 AS TIES GO BY

This interactive web application has been designed

and developed to allow users to register, access, and

share their memories, especially those associated with

media like music and movies, taking into account the

results of the user survey. It integrates As Music Goes

By (Moreira and Chambel, 2019; Serra and Chambel,

2020), where users can search, visualize, and explore

music and movies from complementary perspectives

of music versions, artists, quotes and movie

soundtracks over time; and the EmoJar application,

also developed in the context of the AWESOME

project (Chambel et al., 2023). In this paper, we

emphasize this new perspective centered around

personal and shared autobiographical memories,

connecting or tying media with life events and the

people involved, by the name of As Ties Go By.

Memories can be registered in a personal space,

like in a journal; and also shared in groups, like fam-

ily or friends, at the time they happened, not nec-

essarily when they are registered. In each of these

spaces, memories can be represented in different per-

spectives. Main features are described next, and

illustrated in Figs. 1-2, exemplifying navigation.

Sharing and Accessing Autobiographical Memories Tied with Media

677

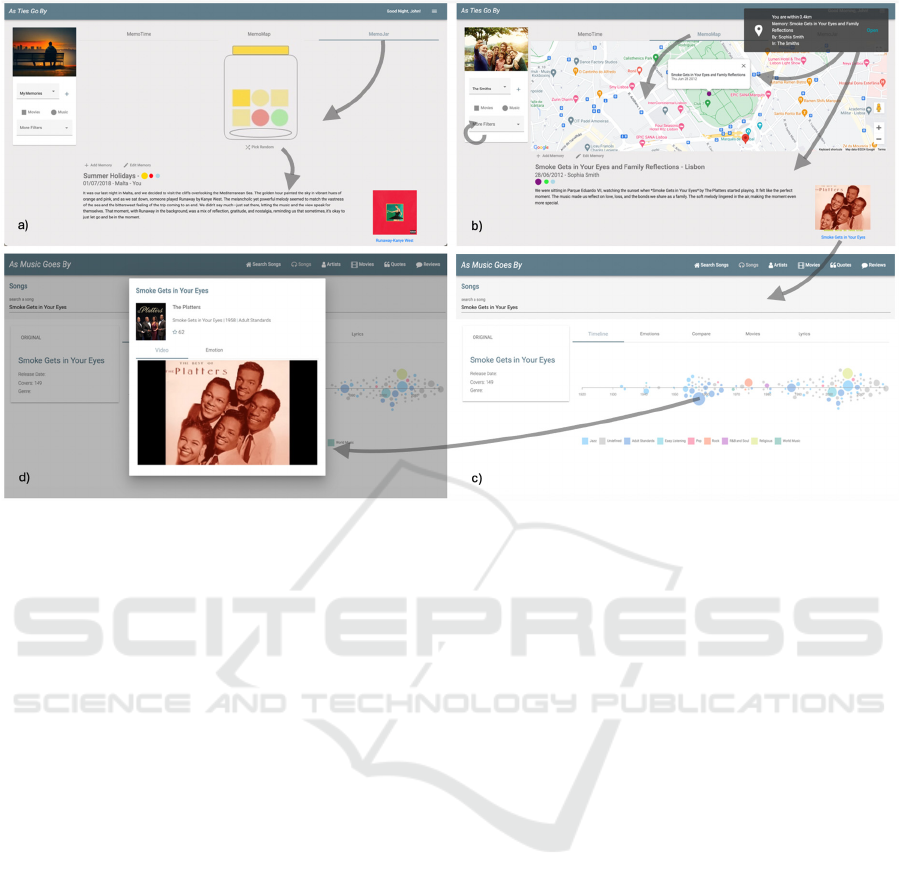

Figure 1: As Ties Go By - MemoTime View in “My Memories” Space: (a) MemoTime view (1st tab on the top) showing

timeline with memories, and exemplifying the access to a memory detail below the timeline; (b) MemoTimeSpiral view.

Memory Spaces: When users first land in the

application, they are met with their own memories in

the ”My Memories” personal space (Fig. 1a). They

can switch to their group memory spaces (e.g. “The

Smiths”, Fig. 2b), choosing from a scrollable list on

the left, below the identification of the current space.

Memory Views:

The first View displayed when

users enter a memory space (Fig.1) is MemoTime:

Memory markers are placed chronologically on the

dates they occurred on an horizontal timeline,

offering a familiar and comprehensive overview of

time within the memory space. For an alternative

perspective, based on spirals (Weber et al., 2001),

aligned with the “cyclic” representation identified in

the user survey, and the annual circle we go around

the sun: users can switch to the MemoTimeSpiral

View (Fig. 1b), accessible in the MemoTime tab.

Time flows from the bottom to the top of the spiral,

each lap representing a year. This design highlights

temporal patterns within the memory space, such as

recurring events like summer holidays or Christmas.

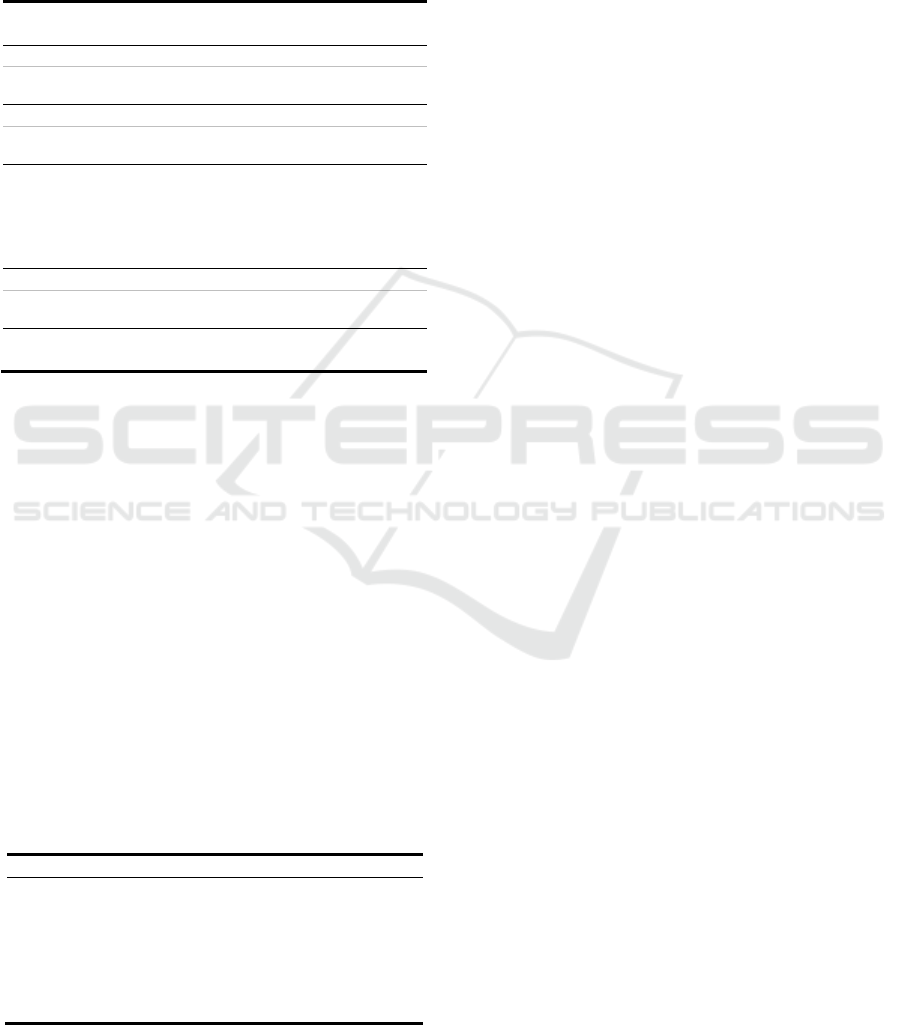

On MemoMap View (Fig. 2b) users have a world

map, where they can see the memories in the places

they happened, depending on the zoom used in this

Google Maps view. Like in the other views, filters can

be applied, here with a geographical perspective.

On MemoJar View (Fig. 2a), inspired by EmoJar

(Chambel and Carvalho, 2020), users add their

memories to a happiness jar, and later revisit them, to

remember or relive a happy or treasured memory;

with a twist of serendipity, by randomly picking one.

Memories: In all the Views, memories are

represented by pins, markers, with shape dependent

on media type (circles for music, inspired by cd or

vinyl music records; and squares for movies, inspired

by celuloid film frames); and the color of the main

emotion associated with that memory, based on

Plutchik’s model of emotions (Caldeira et al., 2003).

When clicking a memory pin, it gets highlighted in

the view, and its details appear below (Fig. 1a, 2a,b).

The memory title is followed by its date; location; or

pins reflecting the media type and dominant emotions

(highlighting in front of the title the one that

corresponds to the current Memory View, and

presenting the other ones below; along with author,

media content, and a brief description written by the

user. Music and movies can be accessed via As

Music Goes By (Fig. 2b-c-d), with the opportunity to

access more information and songs contextualized in

movie soundtracks.

To create a new memory, users click the ”Add

Memory” button, below the active tab view, openning

a pop-up form for inputting memory details. After

saving, the memory appears in the various memory

view tabs. Users can also edit memories, openning a

similar form pre-filled with the current details.

Memory Filters: select content to be displayed

on the different Memory Views, for more focused

perspectives and understanding of memory spaces, in

2 types: Media filters accessible via 2 labeled

buttons: Music & Movies, beneath the memory space

list; Hashtag filters in a dropdown list below the

media filter buttons allow users to select one or more

hashtags for filtering. These can signify various

themes like holidays, birthdays, or summer vacations.

Notifications: based on time and space. Users are

notified about memory anniversaries and memories

that happened close to their current location. Users

can click on them to access corresponding memories:

the memory pin and the details below (Fig.2b).

See Figure captions

for

more detailed descriptions

of the exemplified navigation among different views.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

678

Figure 2: As Ties Go By – MemoJar and MemoMap Views, Notifications and Access to Music and Movies: (a) MemoJar

View’s ’Pick Random’ button retrieves a memory: (b) MemoMap View, transitioning from the personal to a group Memory

Space (“The Smiths”), then receiving a location-based notification, and by clicking on it, the notified memory of The Smiths

Family is accessed with details, below, and highlighted in a close-up of the map, where it happened, in relation to the current

user location, near by; this memory is about the first ball of the user’s grand parents, where they danced to the song Smoke

Gets in Your Eyes; (c) Accessing the memory song: Smoke Gets in Your Eyes to watch and navigate it, in As Music Goes

By (Moreira and Chambel, 2019): first contextualized in its different versions; and (d) playing the song by the Platters.

5 USER EVALUATION

A preliminary user evaluation was conducted to

assess perceived usefulness, usability, and user

experience in the As Ties Go By interactive features.

Methodology: A task-focused evaluation was

carried out using semi-structured interviews and

direct observation as users interacted with the

application and all its features. Before the tasks,

participants were introduced to the evaluation’s

purpose, answered demographic questions, and

received a brief overview of the application. The

evaluation was based on USE (Lund, 2001), assessing

the perceived Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of

Use for each task on a 5-point scale. After the

evaluation, users were asked to provide an overall

assessment of the application through a global USE

rating, and encouraged to identify their favorite

features, suggest potential improvements, and

describe the application’s perceived qualities,

selecting predefined ergonomic, hedonic and appeal

terms (Hassenzahl et al., 2000).

Participants: The evaluation involved 10

participants, 6 males and 4 females, ages 22-48,

average 30.3. 4 held bachelor’s degrees, 3 had

master’s degrees, 1 had a technical degree, and 1

completed high school. Professionally, they worked

in informatics, health, psychology, business, physics,

and education. All familiar with digital applications

to some extent. Music consumption habits: 9 listened

to music daily, 1 a few times per month, using:

Spotify (7 participants), YouTube (4) and Apple

Music (2). Movie consumption: 5 watched movies 2-

3 times per month, 3 weekly, and 2 monthly. They

also reported using streaming services like

SkyShowtime, Prime Video, Disney+, and Netflix.

Sharing memories: 4 occasionally document or save

important moments, 3 monthly and 3 weekly.

Memory-sharing: 4 occasionally, 3 weekly, and 3

daily. Almost all (9 out of 10) agreed that storing and

sharing memories with family and friends was

important or very important, and 8 found it easy or

very easy to connect memories to media content like

music and movies; overall highlighting the relevance

of the platform’s purpose.

Sharing and Accessing Autobiographical Memories Tied with Media

679

Results: The users completed all tasks efficiently

and with minimal hesitation, overall having a positive

experience with the application, with main features

highlighted in Figs. 1 and 2; and the USE results

summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: USE evaluation of As Ties Go By by feature.

Scale:1-5: lowest-highest); M=Mean; SD=Std. Deviation

U S E

F# Feature

M SD M SD M SD

1 MemoTime view (mean)

4.3 0.8 4.3 0.7 4.7 0.6

1.1 MemoTime 4.4 0.7 4.5 0.5 4.8 0.4

1.2 MemoTime Spiral 4.1 0.9 4.0 0.9 4.5 0.7

2 Filters (mean)

4.6 0.6 4.8 0.4 5.0 0.2

2.1 Media Filters 4.6 0.6 4.8 0.4 5.0 0.0

2.2 Hashtag Filters 4.5 0.5 4.8 0.4 4.9 0.3

3 Memor

y

Entr

y

Creation

4.9 0.3 4.8 0.4 4.7 0.5

4 MemoMap View

4.8 0.4 4.9 0.3 4.9 0.3

5 MemoJar View

3.7 0.9 4.0 0.8 4.9 0.3

6 Notifications (time&place)

4.5 0.5 3.5 0.7 4.8 0.4

7 Access to Music&Movies

4.2 0.5 4.3 0.4 4.0 0.8

8 Memory Spaces (mean)

4.7 0.4 3.6 0.8 4.8 0.5

8.1 Memory Spaces: Types 4.5 0.5 3.5 0.7 4.8 0.4

8.2 Memory Spaces: Creation 4.9 0.3 3.7 0.9 4.7 0.5

Total by Feature (mean)

4.6 0.6 4.3 0.6 4.7 0.4

Global Evaluation

4.3 0.4 4.1 0.9 4.6 0.6

Global Evaluation: Overall, participants rated the

application quite positively in terms of usefulness

(U:4.3), satisfaction (S:4.1) and especially ease of use

(E:4.6). Interesting to note that, in spite of high scores

for other features during the evaluation, at the end,

when asked about preferences, they especially

enjoyed features that are more specific to what As

Ties Go By is all about: MemoTime and MemoMap

views, time and location-based Notifications, and the

contextualized Access to Music and Movies from

memories. As final suggestions, they highlighted the

importance of developing further mobile features and

related notifications, citing benefits like easier real-

time capture of moments; and improving media

connections to services like IMDb and Spotify.

Table 2: Quality terms users chose for As Ties Go By.

H: Hedonic; E: Ergonomic; A: Appeal;

bold: more frequent; italics: negative terms

Terms type # Terms type #

Original H 8 Innovative H 3

Understandable E 7 Aesthetic A 3

Simple E 7 Attractive A 3

Interestin

g

H 6 Predictable E 2

S

y

m

p

athetic A 6 Trustworth

y

E 2

Pleasant A 5 Unaesthetic A 1

Goo

d

A 5

Finally, users were asked to describe the applica-

tion using quality terms (Hassenzahl et al., 2000),

results in Table 2. The chosen terms are reasonably

well distributed among the (H)edonic, (E)rgonomic

and (A)ppeal qualities. Original was the most chosen

term; then Understandable and Simple; Interesting

and Sympayhetic, then Pleasant and Good, all chosen

by half or more subjects. Just one negative term

chosen: Unaesthetic (by 1 subject), but superseded by

the opposite positive term: Aesthetic (by 3). These

results align and complement the feedback from the

feature evaluation and the user comments.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND

PERSPECTIVES

This paper addressed the concept and introduced

interactive means to capture, visualize and link

memories with media, such as movies and music,

along time and space, with an emotional impact, and

the potential to enhance memory recall and foster

deeper connections, by sharing important memories

and moments that happened in our lives with others,

like family and friends. User feedback in the

evaluation highlighted features like MemoTime,

MemoMap, notifications and access to music and

movies as particularly engaging; with most chosen

quality terms including Original, Interesting,

Sympathetic, Pleasant, Simple and Understandable;

and the application received quite good ratings in

usefulness, satisfaction, and ease of use. Quite

relevant and encouraging as a proof of concept, with

potential for future developments

Future work includes refining, based on the

evaluation and user feedback, and further extending

the interactive features. In particular, main challenges

and perspectives for the future include:

To explore further the spiral representation, in 3D,

and other time representations, and extend search,

based on time and emotions (Caldeira et al., 2023) in

this context. To go beyond a web application to

include a dedicated mobile app with seamless

crossplatform functionality and native notification

support, to improve flexibility and engagement. To

extend the notifications, beyond time and space,

taking into account the emotions associated with the

memories and felt by the users, and other contextual

information, including ambient music detection to

trigger related memory recall in serendipitous ways.

To go towards user-generated content at a larger

scale, and consider integrating and accessing media

content in larger platforms like IMDb and Spotify.

HUCAPP 2025 - 9th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

680

To allow memories to have richer ways for user

expression in this context; linking to songs on the

movies’ soundtracks; and the possibility of having

trajectories, instead of a static position, on the map.

In group spaces there is a potential challenge of

having different versions or perspectives of the same

events. Who is right or how can they cohexist as

shared memories? Approaches like Storytelling could

be explored here, with interactive digital narratives,

for its adequacy in complex, causal and multi-

sequential stories (Silva et al., 2021). This type of

biographical information could as well be explored in

reminiscence therapy with potencial benefits in social

interactions and self-esteem.

Finally, it is also important to account for privacy,

while providing significant ties involving memories

with media.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by FCT through

the AWESOME project, ref. PTDC/CCIINF/29234/

2017, and the LASIGE Research Unit, ref. UIDB/

00408/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00408/

2020) and ref. UIDP/00408/202 (https://doi.org/10.

54499/UIDP/00408/2020).

REFERENCES

Bentley, F. R., Basapur, S., and Chowdhury, S. K. (2011).

Promoting intergenerational communication through

location-based asynchronous video communication.

In Proc. of UbiComp 2011), ACM, 31-40.

Bietti, L. M. (2010). Sharing memories, family conversa-

tion and interaction. Discourse & Society, 21(5):499–

523.

Byrne, J. H. (2017). Learning and memory: a comprehen-

sive reference. Academic Press.

Caldeira, F., Lourenço, J., and Chambel, T. (2023). Happy

or Sad, Smiling or Drawing: Multimodal Search and

Visualisation of Movies Based on Emotions Along

Time. VISIGRAPP (2: HUCAPP), 85-97. Best Paper

Award.

Chambel, T., Arriaga, P., Fonseca, M. J., Langlois, T.,

Postolache, O., Ribeiro, C., Piçarra, N., Alarcão, S. M.,

and Jorge, A. (2023). That's AWESOME: Awareness

While Experiencing and Surfing On Movies through

Emotions. In Proc. of ACM IMX Workshops 2023, 110-

117.

Chambel, T. and Carvalho, P. (2020). Memorable and

Emotional Media Moments: reminding yourself of the

good things!, VISIGRAPP/ HUCAPP 2020, 86-98. Best

Paper Award.

Chambel, T., Oliveira, E. and Martins, P. (2011). Being

happy, healthy and whole watching movies that affect

our emotions. In Proc. of ACII 2011, 35-45. Springer.

Coser, L. A., editor (1992). On Collective Memory. Uni-

versity of Chicago Press.

Denby, R. W., Gomez, E., and Alford, K. A. (2016). Pro-

moting well-being through relationship building: The

role of smartphone technology in foster care. Journal of

Technology in Human Services, 34(2):183–208.

Elias, A. and Brown, A. D. (2022). The role of intergener-

ational family stories in mental health and wellbeing.

Frontiers in Psychology, 13.

Hanich, J., Wagner, V., Shah, M., Jacobsen, T., and

Menninghaus, W. (2014). Why we like to watch sad

films. The pleasure of being moved in aesthetic

experiences. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and

the Arts, 8(2), 130.

Harris, C. B., Paterson, H. M., and Kemp, R. I. (2008).

Collaborative recall and collective memory: What

happens when we remember together?. Memory, 16(3),

213-230.

Hassenzahl, M., Platz, A., Burmester, M, and Lehner, K.

(2000). Hedonic and Ergonomic Quality Aspects

Determine a Software’s Appeal. In ACM CHI 2000.

pp.201-208.

Holland, A. C. and Kensinger, E. A. (2010). Emotion and

autobiographical memory. Physics of Life Reviews,

7(1):88–131.

Jakubowski, K., Belfi, A. M., and Eerola, T. (2021).

Phenomenological differences in music-and television-

evoked autobiographical memories. Music Percep-tion:

An Interdisciplinary Journal, 38(5):435–455.

Kubrak, T. (2020). Impact of films: Changes in young peo-

ple’s attitudes after watching a movie. Behavioral Sci-

ences, 10(5), 86.

Larsen, S. F., Thompson, C. P., and Hansen, T. (1996)..

Time in autobiographical memory. Remembering our

past: Studies in autobiographical memory, 129-156.

Lund, A. M. (2001). Measuring usability with the use ques-

tionnaire. In Usability interface, pp.3–6.

Moreira, A. and Chambel, T. (2019). This music reminds

me of a movie, or is it an old song? an interactive

audiovisual journey to find out, explore and play. In

VISIGRAPP (1: GRAPP), pp. 145–158.

Serra, V., and Chambel, T. (2020). Quote Surfing in Music

and Movies with an Emotional Flavor. In VISIGRAPP

(2: HUCAPP), pp. 75-85.

Silva, P., Gao, S., Nayak, S., Ramirez, M., Stricklin, C., and

Murray, J. (2021). Timeline: An authoring platform for

parameterized stories. In Proc. of ACM IMX 2021,

pp.280-283.

Van Den Bosch, C., Peeters, N., & Claes, S. (2022). More

weather tomorrow. engaging families with data through

a personalised weather forecast. In Proc. of ACM IMX

2022, pp.1-10.

Van Dijck, J. (2007). Mediated memories in the digital age.

Stanford University Press.

Weber, M., Alexa, M., and Müller, W. (2001). Visualizing

time-series on spirals. In Infovis, Vol. 1. 7–14.

Sharing and Accessing Autobiographical Memories Tied with Media

681