Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness

Emerson Veiga

a

, Nabson Silva

b

, Bruno Gadelha

c

, Hor

´

acio Oliveira

d

and Tayana Conte

e

Institute of Computing, Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

Keywords:

Dark Patterns, Games, Personal Opinion Survey, Empirical Study.

Abstract:

Dark patterns (DPs) are manipulative design strategies that exploit players’ cognitive biases, often at their

expense. DP in games can negatively affect players’ experiences by coercing them into unwanted behaviors,

often without informed consent. While previous research has categorized DPs and explored their impacts,

an empirical evaluation of their perceived harmfulness remains unexplored. This study aims to create a cat-

alog of DP and evaluate players’ perceptions of them to gather insights into how they are experienced and

understood by players. We extracted DPs and their definitions from prior academic work, refining them with

examples from community forums. To evaluate players’ perceptions, we developed a survey to assess each

DP’s harmfulness, problematic nature, and prevalence. We surveyed 30 participants representing a range of

gaming engagement levels. Statistical tests were conducted to compare harmfulness scores across different

patterns, identifying significant differences among them. Additionally, qualitative analysis provided insights

into players’ experiences and perceptions, highlighting key concerns regarding specific Dark Patterns. The

results provide valuable insights into players’ perceptions of DPs and how they may be unaware of these pat-

terns, aiming to raise awareness and reduce their use in game design.

1 INTRODUCTION

The design of video games often aims to create en-

gaging and enjoyable experiences. However, not

all design practices prioritize the players’ best inter-

ests. A notable example is the use of Dark Patterns

(DPs). According to Brignull (2010), Dark Patterns

are intentional design strategies that exploit cogni-

tive biases or manipulate users into making decisions

against their best interests. Initially introduced in

user interface design (Brignull, 2010), Dark Patterns

have since been identified and studied in the context

of video games, where their impact can be particu-

larly pronounced (Zagal et al., 2013). These patterns

can coerce players into actions that are not fully con-

sensual, such as excessive spending, tedious game-

play, or social pressures to engage. While some ar-

gue that these mechanics are necessary for commer-

cial success, their negative impact on players raises

ethical concerns, ranging from frustration to financial

harm (Zagal et al., 2013; Aagaard et al., 2022).

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-6555-9815

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8617-4201

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7007-5209

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2022-7950

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6436-3773

Although prior studies have identified and catego-

rized Dark Patterns, their focus has often been theo-

retical or qualitative, with limited empirical evidence

on how harmful players perceive these patterns to

be (Zagal et al., 2013; Aagaard et al., 2022; Dahlan

and Susanty, 2022). Furthermore, the definitions and

examples of Dark Patterns in the literature need more

systematization to bridge theoretical knowledge with

practical applications in game design. This reveals a

gap in the existing literature regarding the severity of

harm caused by Dark Patterns and how players inter-

act with them.

While previous research has categorized dark pat-

terns and examined their ethical and psychological

impacts, a comprehensive catalog tailored to games,

enriched with real-world examples, and systemati-

cally analyzed for harmfulness is still lacking. To fill

this gap, we developed a detailed catalog of Dark Pat-

terns in games, categorized and supported by exam-

ples drawn from player communities. We conducted a

survey to assess players’ perceptions of each pattern’s

harmfulness, problematic nature, and prevalence. We

applied statistical analyses to identify differences in

harmfulness across patterns and generate rankings.

Additionally, we analyzed the feedback provided by

participants in open-ended questions to gain further

470

Veiga, E., Silva, N., Gadelha, B., Oliveira, H. and Conte, T.

Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness.

DOI: 10.5220/0013365800003929

In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 2, pages 470-481

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

insights into their perceptions.

Our findings reveal significant variations in how

players perceive the harmfulness of Dark Patterns.

For instance, patterns like Impersonation stood out for

their controversial nature and the challenges partic-

ipants faced in fully grasping their examples, high-

lighting the need for more transparent communica-

tion of such patterns in the industry. On the other

hand, most patterns were perceived with high clar-

ity, demonstrating the reliability of the catalog as a

tool for understanding these practices. These find-

ings underscore the nuanced impact of Dark Patterns:

while some are widely recognized as harmful, oth-

ers may go unnoticed despite their pervasive presence

in games. This research provides a foundation for

addressing the ethical implications of game design,

offering insights that can guide developers in mini-

mizing harm and fostering a more player-centered ap-

proach to design. Additionally, the rankings of harm-

fulness, problematic nature, and prevalence serve as a

practical framework for evaluating and mitigating the

use of Dark Patterns in games.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2

presents the definition of Dark Patterns and related

work; Section 3 outlines the methodology of this

study; Section 4 presents the catalog of Dark Pat-

terns, including definitions and examples of each one;

Section 5 presents the quantitative and qualitative re-

sults; Section 6 delves into the implications of the re-

sults; Section 7 addresses the threats to validity and

the measures taken to mitigate them; and Section 8

concludes the paper by summarizing the key findings,

contributions, and directions for future work.

2 BACKGROUND

This section explores the foundational concepts of

dark patterns and discusses related work. It provides

readers with the essential background to understand

the motivations and significance of this study.

2.1 Dark Patterns in Games

According to Brignull (2010), Dark Patterns (DPs)

are deliberate design strategies implemented in user

interfaces to exploit cognitive biases, guiding users

toward decisions that may not align with their in-

tentions or best interests. These manipulative tech-

niques are often subtle, capitalizing on users’ lack

of information, urgency, or emotional triggers (Gray

et al., 2018). Unlike user-centered design, which pri-

oritizes enhancing user experience and satisfaction,

Dark Patterns are purposefully crafted to benefit busi-

nesses at the expense of user autonomy (Mathur et al.,

2019). Examples include deceptive language, hid-

den fees, and confusing or misled interface designs.

The essence of Dark Patterns lies in their intention-

ality; they are not accidental flaws but carefully en-

gineered mechanisms to achieve specific outcomes,

such as increased spending, prolonged engagement,

or the surrender of personal data. While their origin is

rooted in e-commerce and user interface design (Gray

et al., 2018), their application has expanded into vari-

ous domains, including video games, where their im-

pacts can range from frustration to significant finan-

cial harm (Zagal et al., 2013).

Zagal et al. (2013) defines dark patterns in games

as systemic features designed to create negative expe-

riences, such as frustration, coercion, or regret, often

without the player’s informed consent. These patterns

are not accidental; they are purposefully implemented

to increase player retention, engagement, or moneti-

zation, frequently at the expense of user satisfaction.

In this study, we adopted the three primary categories

of Dark Patterns in games as defined by Zagal et al.

(2013):

• Temporal Dark Patterns in Games: manipulate

players’ time, often requiring repetitive tasks or

specific schedules to progress.

• Monetary Dark Patterns in Games: exploit

players’ financial investments through mecha-

nisms such as microtransactions or loot boxes.

• Social Capital Dark Patterns in Games: lever-

age social relationships, sometimes coercively, to

encourage engagement.

Dark patterns in games are particularly controver-

sial due to their intersection of entertainment and ex-

ploitation (Zagal et al., 2013). While some mechan-

ics may enhance gameplay when used ethically, their

misuse can lead to significant negative consequences

for players, such as financial loss, addiction, or re-

duced autonomy (Aagaard et al., 2022).

2.2 Related Work

Beyond games, dark patterns have been extensively

documented in other domains. Brignull (2010) high-

lighted their presence in e-commerce, where manip-

ulative designs nudge users toward undesired pur-

chases. Gray et al. (2018) analyzed dark patterns in

social media platforms, showing how they encourage

data sharing and prolonged engagement. In mobile

applications, Greenberg and Pashang (2020) identi-

fied patterns that leverage persistent notifications and

gamification to retain users. Additionally, Mathur

et al. (2019) revealed how health apps exploit user

Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness

471

anxiety to extract sensitive information, while McCoy

and Luger (2020) described the use of autoplay and

cancellation barriers in streaming services to increase

consumption.

The ethical concerns surrounding dark patterns in

games have garnered increasing attention in Human-

Computer Interaction (HCI) and game design re-

search. Zagal et al. (2013) laid the groundwork

for understanding dark patterns in games by cate-

gorizing them and exploring their ethical implica-

tions. They argue that these patterns intentionally

create negative experiences, often to maximize prof-

its. This work has been instrumental in framing dis-

cussions about the trade-offs between player satisfac-

tion and developer goals. Aagaard et al. (2022) ex-

amined how dark patterns are implemented in mobile

games and their effects on players and industry pro-

fessionals. Their findings highlight the complexity of

ethical game design, noting that dark patterns often

emerge from industry pressures rather than overt ma-

licious intent. They advocate for more transparent and

player-centered design practices to mitigate harm.

Dahlan and Susanty (2022) identified prevalent

dark patterns in casual mobile games using heuris-

tic evaluation. Their quantitative approach provides

insights into the severity and frequency of patterns

such as Grinding and Pay to Skip. This research

offers a framework for evaluating dark patterns and

highlights their potential harm to player experiences.

Flankkum

¨

aki and S

¨

oderholm (2020) investigated the

impact of dark patterns on user desirability in Candy

Crush Saga. Their research highlights how specific

manipulative design patterns influence players’ en-

gagement and decisions to continue or quit the game.

Through a user experience survey, they identified that

temporal and monetary dark patterns, such as time-

limited boosters and excessive difficulty without in-

game purchases, significantly decrease the game’s

perceived enjoyment. Hodent and Others (2024) ex-

plore ethical concerns in the gaming industry, high-

lighting issues such as dark patterns, microtransac-

tions, gambling-like mechanics, and exploitative de-

sign choices. Their work provides an evidence-based

perspective on safeguarding players and developers

from manipulative and harmful game design prac-

tices. This aligns with our research focus on dark

patterns in games, reinforcing the need for systematic

evaluations of their harmfulness and prevalence from

a player-centered perspective.

Together, these studies underline the growing

need for ethical guidelines and countermeasures to re-

duce the occurrence of dark patterns in games. De-

spite these efforts, a significant gap remains in cat-

aloging dark patterns systematically and assessing

their impact quantitatively, particularly from the play-

ers’ perspective. This study addresses this gap by pre-

senting a comprehensive catalog of game dark pat-

terns, their categorizations, and an empirical evalua-

tion of their perceived harmfulness and prevalence.

3 METHODOLOGY

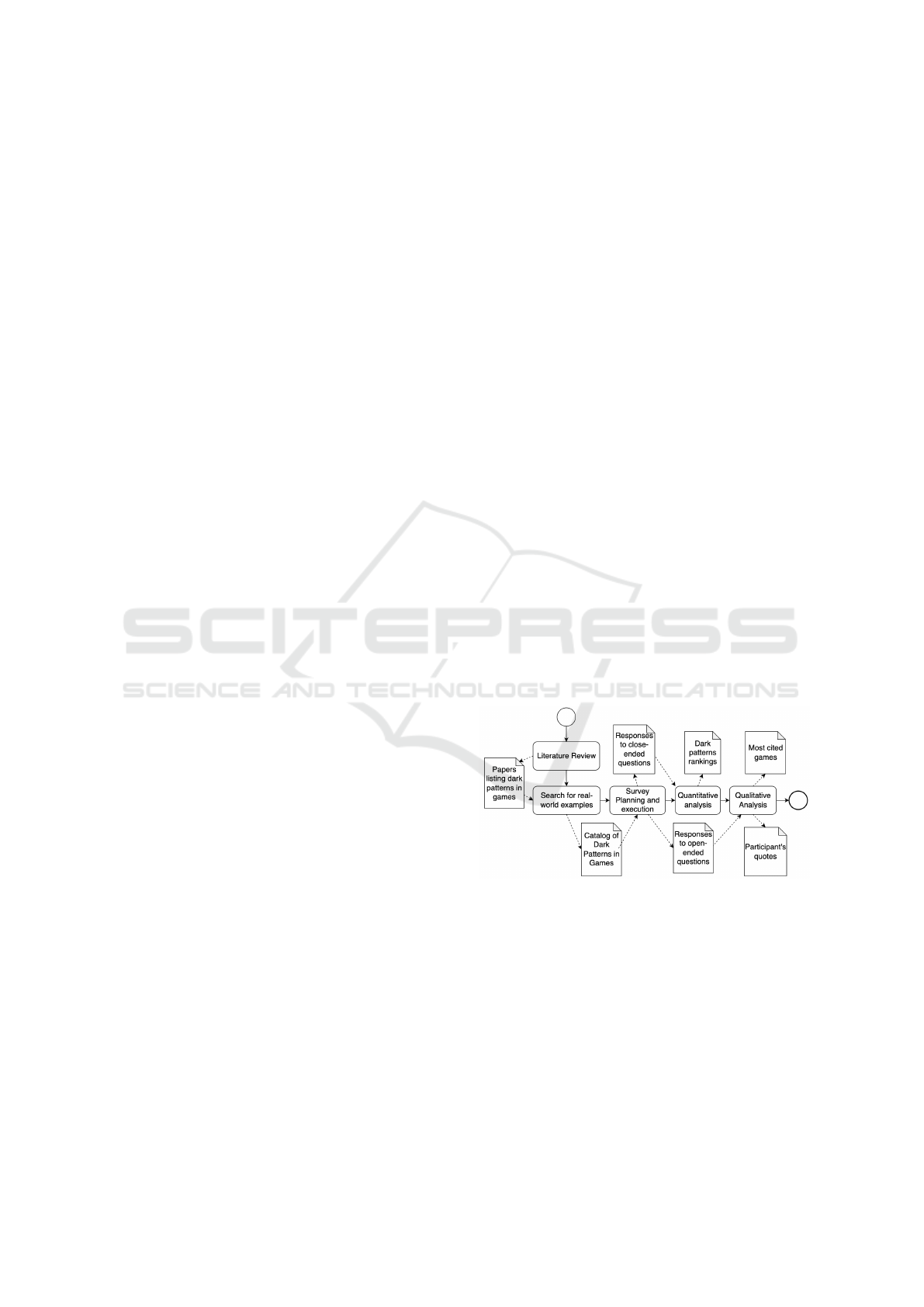

Figure 1 illustrates the process of creating the catalog

of dark patterns in games and evaluating them through

an empirical study. The process began with a litera-

ture review to search for papers listing dark patterns

in games. The next step involved gathering real-world

examples from community discussions on Reddit fo-

rums and Discord groups. By combining the defini-

tions of dark patterns with these real-world examples,

we developed our catalog of Dark Patterns in Games.

We then designed a survey to evaluate each dark pat-

tern’s definitions, examples, and perceived harmful-

ness. We conducted a pilot study to refine and assess

the survey instruments. The survey included closed-

ended and open-ended questions, providing the data

for subsequent analyses. The quantitative analysis

measured the harmfulness of each dark pattern and

generated rankings based on their harmfulness, preva-

lence, and problematic nature. Finally, a qualitative

analysis of the open-ended responses highlighted par-

ticipant quotes and identified the most cited games as-

sociated with these patterns.

Figure 1: Diagram illustrating the methodology of this

study.

This study aims to catalog dark patterns in games

and quantitatively measure their perceived harmful-

ness. The dark patterns included in the catalog were

identified based on the works of Zagal et al. (2013);

Aagaard et al. (2022); Dahlan and Susanty (2022).

We primarily adapted definitions from Zagal et al.

(2013), as their work provides foundational insights

into dark patterns in game design. Aagaard et al.

(2022) contributed to understanding how dark pat-

terns operate in mobile games and the tension be-

tween engagement and manipulation, enriching the

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

472

contextual scope of our catalog. Dahlan and Susanty

(2022) provided a framework for identifying patterns

in casual mobile games, guiding the selection of pat-

terns most relevant to player experiences. We gath-

ered real-world examples for each pattern through re-

search in community discussions across online fo-

rums, such as Reddit

1

, and gaming-focused Discord

groups. This process involved carefully identifying

and analyzing relevant conversations to extract illus-

trative examples. We choose these examples for their

clarity and ability to demonstrate each Dark Pattern,

enriching the catalog by grounding it in authentic

player experiences. This step validated the patterns

and ensured the catalog reflects the diverse ways these

Dark Patterns manifest in real gaming scenarios.

We designed a survey to collect participants’ per-

ceptions to evaluate dark patterns’ prevalence, harm-

fulness, and problematic nature. To enhance clar-

ity and conciseness in question formulation, we con-

sidered the principles outlined by Kitchenham and

Pfleeger (2008) as a reference for survey design. We

conducted a pilot study with two participants to evalu-

ate the catalog and the questionnaire. Feedback high-

lighted two main issues: the definitions of the dark

patterns were overly lengthy, and the examples pro-

vided needed to be adequately illustrative. Based on

this feedback, we simplified the definitions, polished

the questions, and refined the examples to enhance

clarity and relevance. Additionally, three researchers

reviewed the revised survey to ensure consistency and

comprehensibility before finalizing it. The final ver-

sion incorporated these refinements to improve partic-

ipant understanding. We used convenience sampling

and referral-chain methods (Babbie, 2014) to recruit

participants, reach out to players, and share the online

survey link in gaming forums and Discord channels

to ensure a diverse yet accessible sample.

We divided the survey into three sections, combin-

ing closed-ended and open-ended questions to quan-

tify participants’ perceptions of harmfulness, prob-

lematic nature, and prevalence of the identified Dark

Patterns. Additionally, we included a consent form,

ensuring participants provided informed consent to

participate voluntarily. We assured participants

anonymity, and all data collected was anonymized to

maintain privacy and foster honest feedback.

The first section aimed to characterize participants

by gathering information about their gaming habits,

such as the time spent gaming per week and the types

of games they play. We asked the following questions

to help contextualize the feedback provided and en-

sured that the sample includes a diverse representation

of players, enhancing the study’s generalizability:

1

https://www.reddit.com/

1. How many hours per week do you spend playing

games?

(a) Less than 5 hours

(b) Between 5 and 10 hours

(c) Between 10 and 20 hours

(d) Between 20 and 30 hours

(e) More than 30 hours

2. What genres of games do you usually play?

(multiple-choice)

(a) MOBA (Multiplayer Online Battle Arena)

(b) FPS (First Person Shooter)

(c) Battle Royale

(d) Action/Adventure

(e) Sports Games

(f) Single Player RPG (Role Playing Game)

(g) Fighting Games

(h) Racing Games

(i) Others (open-ended)

The second section focused on validating each of

the 13 dark patterns in the catalog. We asked the

participants to evaluate each Dark Pattern based on

its clarity, harmfulness, and real-world presence. We

used a 10-point Likert scale (Likert, 1932) ranging

from ‘Not Harmful’ to ‘Very Harmful’ for the ques-

tion ‘How harmful do you think this dark pattern

is?’. This choice was guided by established prac-

tices in empirical software engineering, as discussed

by Wohlin et al. (2012), who recommend the system-

atic use of quantitative scales to capture nuanced par-

ticipant feedback while maintaining statistical rigor.

This scale improves sensitivity in measuring subjec-

tive evaluations, as outlined in evidence-based soft-

ware engineering practices (Kitchenham and Pfleeger,

2008). Additionally, this section included open-ended

questions, allowing participants to provide detailed

insights. The following questions composed the sec-

ond section of the survey:

1. Is the definition and example of Grinding clearly

stated? (Yes/No)

2. If not, what is unclear?

3. Considering the provided definition, do you con-

sider this issue to be a problem? (Yes/No)

4. If you’d like to justify, why do you think so?

5. Have you noticed this dark pattern in any game?

(Yes/No)

6. If yes, in which game?

7. How harmful do you think this dark pattern is? (1

– Not Harmful / 10 – Very Harmful)

Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness

473

The third section allowed participants to share

their insights and experiences. This section aimed

to capture qualitative data that could supplement the

quantitative findings, though the primary focus of the

analysis was on statistical evaluations. The follow-

ing questions were presented to the participants in this

section of the survey:

1. Do you agree that a forum-like website, where

players could vote on games that use these pat-

terns in their development, would help reduce

their usage by companies? (Yes, I agree/No, I dis-

agree)

2. If you’d like to justify, why do you think so?

3. How would you feel knowing, before playing a

game, that the company responsible frequently

uses these patterns in the development of their

other games?

4. How can this catalog be used to reduce the occur-

rence of the listed Dark Patterns?

5. Do you have any suggestions to improve the Dark

Patterns in Games catalog?

We used descriptive statistics, including mean,

mode, median, and standard deviation, to summarize

participant responses to the question ‘How harmful

do you think this dark pattern is?’. We conducted

a series of statistical tests to test the hypothesis re-

garding differences in perceived harmfulness among

dark patterns. Initially, we employed the Shapiro-

Wilk test (Shapiro and Wilk, 1965) to assess whether

the score samples for each pattern followed a normal

distribution. Since data significantly deviated from

normality, we chose non-parametric tests for further

analysis. To examine differences in perceived harm-

fulness among dark patterns, we utilized the Kruskal-

Wallis test (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952). To compare

pairs of distributions, we applied Dunn’s post-hoc

test (Dunn, 1964). Ultimately, we generated three

rankings of Dark Patterns to highlight the most and

the least harmful, problematic, and prevalent ones.

Finally, we analyzed the open-ended responses to

gain further insights into participants’ perceptions of

each dark pattern. It complemented the quantitative

findings and provided additional context for under-

standing how players experience them. Additionally,

we could identify the games with the most dark pat-

terns perceived by participants.

4 CATALOG OF DARK

PATTERNS IN GAMES

This section presents the catalog of Dark Patterns

evaluated in the survey. Each dark pattern includes its

name, category, definition, and real game examples.

4.1 Grinding

Category: Temporal Dark Patterns

Definition: Grinding refers to any repetitive and

tedious activity required to achieve a goal in a game.

It is typically used when no more convenient meth-

ods of progression are available. This approach often

coerces players to spend significantly more time than

initially intended.

Example: In role-playing games (RPGs) like

Black Desert Online (Abyss, 2015), players must de-

feat monsters to earn in-game currency and items. As

players progress, they realize they must dedicate more

time to keep up with others, creating an endless cycle

as the game is frequently updated with new content.

4.2 Playing by Appointment

Category: Temporal Dark Patterns

Definition: Playing by Appointment occurs when

a game requires players to log in at specific times to

achieve objectives, penalizing those who miss these

designated times. This mechanic pushes players to

adjust their routines around the game. Without penal-

ties for missing these times, this becomes a non-issue.

Example: In online games, events may happen

at set times, such as 8:00 a.m. and 6:00 p.m., and

missing out means forfeiting valuable rewards, lead-

ing players to adjust their schedules. However, this

issue is mitigated in games where these rewards can

be obtained later.

4.3 Endowed Progress

Category: Temporal Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern refers to a misleading

sense of progression ceded to encourage players to

continue playing beyond their initial intent. The ini-

tial advancement is often much faster than the pro-

gression required in later stages, forming a dark pat-

tern.

Example: In a game with a battle pass, the first

few levels are easy to achieve, creating a sense of

progress. However, subsequent levels require much

more time, coercing players to keep playing based on

their initial progress, even if it demands more time

than planned.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

474

4.4 Fear of Missing out

Category: Temporal Dark Patterns

Definition: Fear of Missing Out (F.O.M.O.) is

used in games through daily login rewards, battle

passes, frequent updates, and surprise events with ex-

clusive items. This mechanic pressures players to reg-

ularly check for updates to ensure they get all the po-

tential rewards. The randomness and frequency of

these events increase player anxiety, aggravating this

dark pattern.

Example: In Final Fantasy XIV (Enix, 2010), sur-

prise events can occur at any time, offering rare items

available only for a few hours upon defeating certain

enemies. The unpredictability and frequency of these

updates lead players to remain vigilant and anxious

about missing any opportunity.

4.5 Pay to Skip

Category: Monetary Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern persuades players to

spend money to overcome challenging stages, easing

progression after payment. This creates the illusion

that paying is worthwhile; however, new levels even-

tually require more payments, resulting in frustration

and more significant expenses than anticipated. Pay

to Skip is often linked to Grinding, where players pay

to avoid repetitive tasks.

Example: A player encounters a difficult stage

and buys an item to advance. The following levels be-

come easier, but soon, another challenging stage ap-

pears, prompting more spending and creating a cycle

of unexpected costs.

4.6 Loot Boxes

Category: Monetary Dark Patterns

Definition: Loot Boxes are randomized item con-

tainers, available through gameplay or real money.

The problem lies in the lack of transparency about

the odds of obtaining rare items, often hidden or diffi-

cult to access. Some countries, like China and South

Korea, require companies to disclose these probabil-

ities and set daily purchase limits (Gach, 2018), but

this has yet to be a global standard, leading players to

spend more than they intended.

Example: A player purchases a loot box hop-

ing for a rare weapon but receives only common

items. Unaware of the true odds, they continue buying

boxes, spending far more than they initially planned.

4.7 Invested Value

Category: Monetary Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern exploits the Sunk Cost

Fallacy (Arkes and Blumer, 1985), making players

feel compelled to continue playing due to the time or

money they have already invested. The problem arises

when games continually extend goals, making players

feel that quitting would waste their past investments.

Example: In games like World of Warcraft (En-

tertainment, 2004), players invest years completing

objectives. With each new paid expansion, more

goals are added, compelling players to keep playing

to avoid wasting their invested time and money.

4.8 Pay Wall

Category: Monetary Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern imposes a cost for full

participation in the game. Although payment is op-

tional, non-paying players experience a limited game

or a competitive disadvantage. This pay wall is often

subtle and unexpected, creating frustration and pres-

sure to spend money and forming a dark pattern.

Example: A player starts a free game but soon re-

alizes important areas, characters, or items are locked

behind a pay wall. Their experience is limited with-

out payment, and in competitive games, they cannot

fairly compete with paying players.

4.9 Pre-Delivered Content

Category: Monetary Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern occurs when a game is

marketed as complete but contains locked content that

requires additional payment to access. These locked

features, already present in the game from the start,

are disguised as downloadable content (DLCs), de-

ceiving players who thought they purchased the entire

game.

Example: Fighting games like Mortal Kom-

bat (Games, 1992) are sold as complete, but many

characters and maps are only accessible through extra

payment. These features were part of the game from

launch, leaving players feeling they bought an incom-

plete game and forcing them to pay more to access

everything.

4.10 Monetized Rivalries

Category: Monetary Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern takes advantage of play-

ers’ competitive drive, encouraging them to spend

more to achieve or maintain a desired ranking, such as

Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness

475

on leaderboards, pushing them to spend beyond their

initial budget.

Example: In a game with a leaderboard, players

can buy items or upgrades to improve their ranking.

Seeing their rank threatened, players feel pressured to

spend more money to maintain their competitive sta-

tus, often investing more than they initially intended.

4.11 Social Obligation

Category: Social Capital Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern pressures players to par-

ticipate in group activities to maintain their social sta-

tus in the game. Those who opt out experience slower

progress and lose access to certain content, feeling ob-

ligated to meet group goals.

Example: Guild systems exemplify this pattern,

where leaders assign tasks to members and penalize

non-participants, compelling players to invest more

time in the game to maintain their social standing.

4.12 Impersonation

Category: Social Capital Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern pretends to befriend play-

ers, using their name and image to motivate them to

play more. While its effectiveness has declined over

time, as players recognize the tactic, it persists.

Example: Some games send notifications or mes-

sages that appear as if they are from friends, encour-

aging players to return or perform actions in-game,

attempting to manipulate players into spending more

time playing.

4.13 Social Pyramid Schemes

Category: Social Capital Dark Patterns

Definition: This pattern slows player progress un-

less they recruit others to play, offering exclusive ben-

efits in return. While pyramid schemes are illegal

business models, this system is often covertly embed-

ded in specific game designs.

Example: A game may require players to invite

friends to obtain specific items or advance to new lev-

els. Without these recruits, the player’s progress is

slower or even blocked, promoting the game’s spread

like a pyramid scheme.

5 RESULTS

In this section, we present the analysis of the results

obtained from 30 participant responses to the survey.

Due to the open-access nature of the survey, precise

control over recruitment was not feasible, and the re-

sponse rate could not be determined. Before complet-

ing the survey, all participants signed a consent form

that outlined the purpose of the study, the voluntary

nature of their participation, and their right to with-

draw at any time without any consequences. The con-

sent form also assured participants of the anonymity

of their responses and the confidentiality of all data

collected, reinforcing the study’s commitment to eth-

ical research practices. This analysis includes in-

sights into the harmfulness, prevalence, and clarity of

the dark patterns evaluated. The survey’s questions,

participants’ characterization and complete catalog of

dark patterns used in this research can be found at our

supplementary material

2

.

Most dark patterns achieved 100% clarity in their

definitions and examples. However, Impersonation

was an exception, with six participants reporting dif-

ficulty understanding its definition or example. The

following subsections present the results of partic-

ipants’ characterization, the quantitative analysis of

harmfulness, problematic nature, and prevalence, the

dark pattern rankings, and the analysis of participants’

feedback.

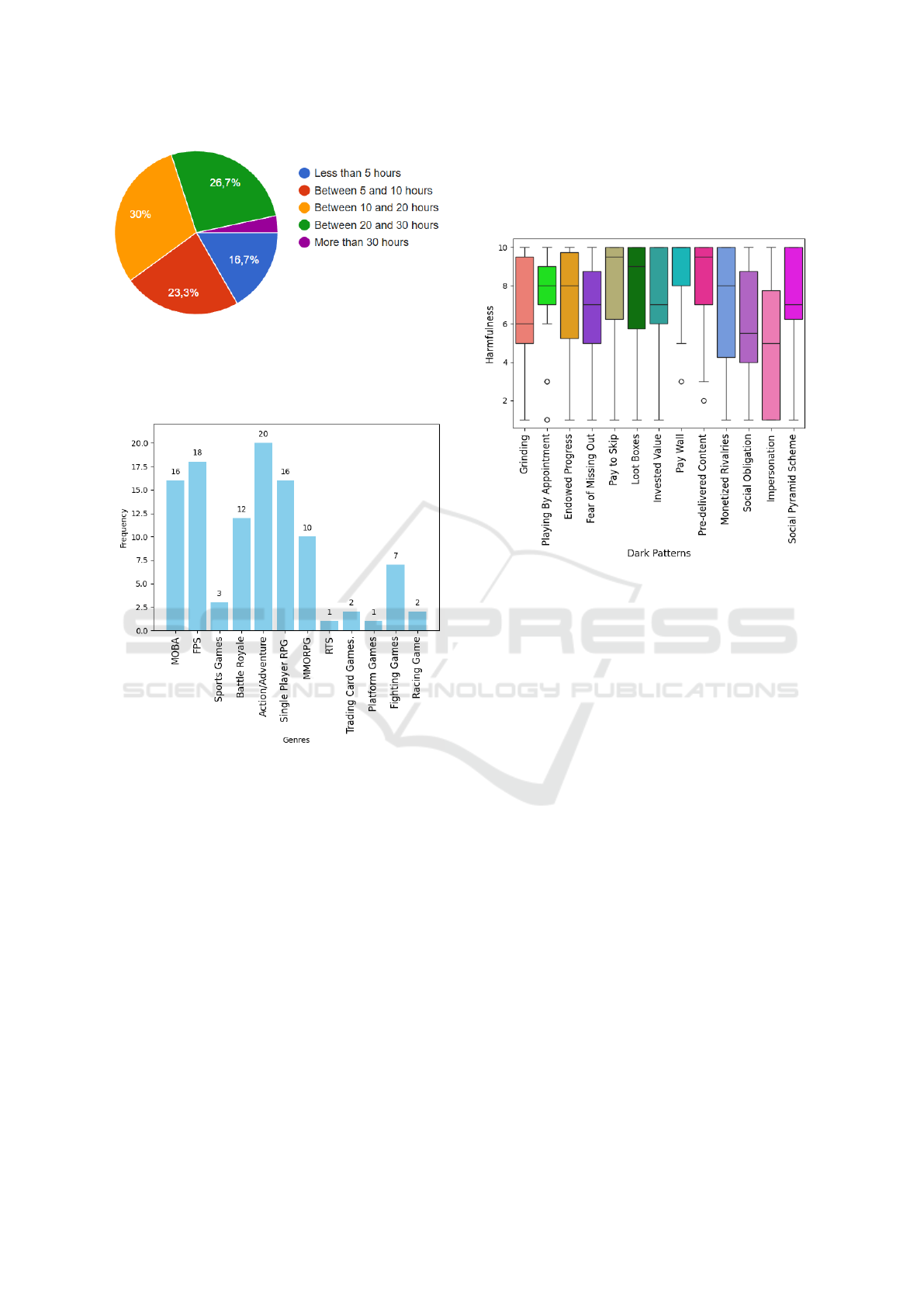

5.1 Participants’ Characterization

Figure 2 shows a Pie chart presenting the responses

to the question, ‘How many hours per week do you

spend playing games?’. The study included partic-

ipants with varying levels of gaming engagement:

16.7% of participants play less than 5 hours per week,

23.3% between 5 and 10 hours, 26.7% between 10

and 20 hours, and 30% between 20 and 30 hours. A

smaller proportion, 3.3%, reported playing more than

30 hours weekly. This distribution highlights a bal-

anced representation of casual, moderate, and inten-

sive gamers, ensuring that the sample captures a broad

spectrum of gaming habits. Such diversity strength-

ens the generalizability of the findings by encompass-

ing varied perspectives on dark patterns across differ-

ent levels of gaming engagement.

Figure 3 shows a bar chart presenting the re-

sponses to the question, ‘What genres of games do

you usually play?’. It illustrates the distribution of

game genres played by the participants, revealing a

diverse range of preferences. Popular genres included

RPGs, FPS, and Action/Adventure, while less fre-

quent choices ranged from Racing to RTS games.

This diversity underscores the varied gaming habits

of the participants, ensuring the study reflects a broad

2

https://github.com/efmantyke/ICEIS-2025

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

476

Figure 2: Pie chart showing the distribution of participants’

weekly gaming hours.

range of player experiences and perspectives on dark

patterns across different game genres.

Figure 3: Bar chart presenting the distribution of game gen-

res played by participants.

5.2 Harmfulness

Figure 4 shows a boxplot presenting the perceived

harmfulness ratings for each dark pattern. Patterns

like Grinding showed a tight interquartile range, indi-

cating consistent agreement among participants about

its harmfulness. In contrast, Impersonation and Pay

Wall patterns displayed wider interquartile ranges, re-

flecting more varied experiences and perceptions of

harm. The analysis reveals that the median harm-

fulness scores for all dark patterns, except Imperson-

ation, fall within the high range on a 1 to 10 scale,

indicating that participants generally perceive these

patterns as highly detrimental. This underscores the

significant negative impact of most dark patterns on

players’ experiences. Outliers were retained in the

analysis, as they provided contextual insights without

significantly deviating from group medians. For ex-

ample, while Impersonation had some unclear ratings,

these did not substantially impact its overall harmful-

ness evaluation.

Figure 4: Boxplot illustrating the harmfulness ratings for

each dark pattern.

We conducted a series of statistical tests to analyze

the perceived harmfulness of dark patterns. First, the

Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that the data significantly

deviated from a normal distribution (p < 0.05), ne-

cessitating non-parametric methods for further anal-

ysis. Using the Kruskal-Wallis test, we confirmed

significant differences in harmfulness scores among

the dark patterns (p < 0.05), indicating that partic-

ipants did not perceive all patterns equally. There-

fore, we applied the post-hoc Dunn test, identifying

specific patterns’ differences. For example, Grind-

ing demonstrated significant differences compared to

Pay Wall, Impersonation, and Pre-delivered Content.

Similarly, Impersonation differed significantly from

most other patterns, except Social Obligation, Grind-

ing, and F.O.M.O. Pay Wall, in particular, showed

significant differences with F.O.M.O., Impersonation,

Social Obligation, and Grinding.

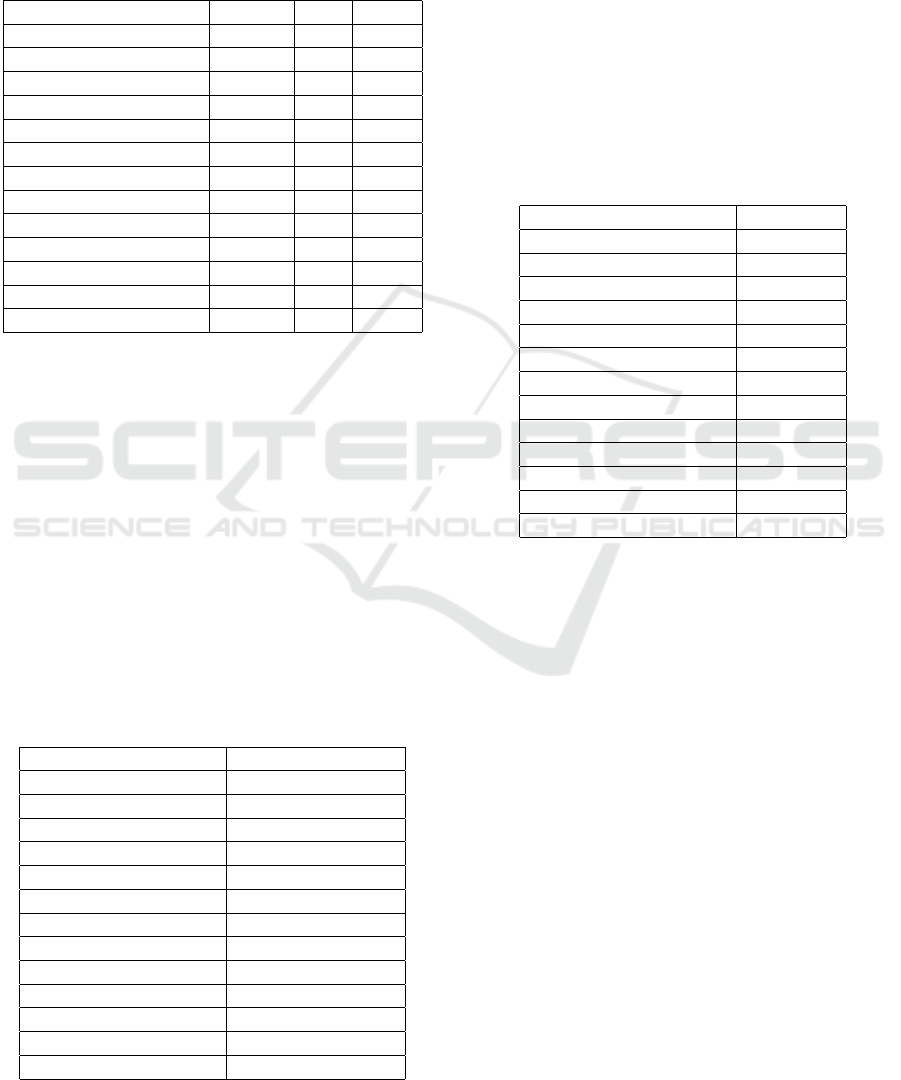

Table 1 presents the ranking of harmfulness. The

ranking is based on the harmfulness median of each

dark pattern. We used the interquartile range fol-

lowed by the median as tiebreaker measures. Pay

Wall emerged as the most harmful pattern, reflecting

players’ frustration with being coerced into spending

money to progress in games. This aligns with partic-

ipants’ feedback, highlighting the disruption of their

autonomy and satisfaction. On the other hand, Grind-

ing was perceived as one of the least harmful patterns,

Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness

477

suggesting that players view it as a standard aspect of

many games rather than a manipulative tactic. The

disparity between these patterns underscores the fi-

nancial and emotional impact that monetary Dark Pat-

terns can have compared to temporal ones.

Table 1: Ranking of Dark Patterns based on harmfulness.

Dark Pattern Median IQR Mean

1. Pay Wall 10.0 2.0 8.83

2. Pre-delivered 9.5 3.0 8.16

3. Pay to Skip 9.5 3.75 7.83

4. Loot Boxes 9.0 4.25 7.83

5. Appointment 8.0 2.0 7.40

6. Endowed Progress 8.0 4.5 7.03

7. Monetized Rivalries 8.0 5.75 7.10

8. Social Pyramid 7.0 3.75 7.03

9. F.O.M.O. 7.0 3.75 6.63

10. Invested Value 7.0 4.0 7.26

11. Grinding 6.0 4.5 6.50

12. Social Obligation 5.5 4.75 5.86

13. Impersonation 5.0 6.75 4.86

5.3 Problematic Nature

Table 2 presents the ranking according to how prob-

lematic the dark patterns are. The ranking is related

to the problematic nature based on the answers to

the question, ‘Considering the provided definition, do

you consider this issue to be a problem?’. As in the

harmfulness ranking, Pay Wall appears in the first po-

sition. Patterns like F.O.M.O. (Fear of Missing Out)

and Playing by Appointment ranked lower, suggest-

ing that while these patterns can be frustrating, they

are less likely to disrupt players’ overall gaming ex-

perience.

Table 2: Ranking of Dark Patterns based on problematic

nature.

Dark Pattern Problematic Nature

1. Pay Wall 100.00%

2. Pre-delivered 93.30%

3. Pay to Skip 86.70%

4. Loot Boxes 86.70%

5. Appointment 86.70%

6. Monetized Rivalries 80.00%

7. Invested Value 80.00%

8. F.O.M.O. 76.70%

9. Endowed Progress 70.00%

10. Social Obligation 66.70%

11. Impersonation 66.70%

12. Grinding 60.00%

13. Social Pyramid 53.30%

5.4 Prevalence

Table 3 presents the ranking of prevalence. The rank-

ing presents the most common dark patterns based on

the answers to the question: ‘Have you noticed this

dark pattern in any game?’. It highlights that Mone-

tary Dark Patterns, such as Loot Boxes and Invested

Value, were the most commonly recognized dark pat-

terns. This suggests that players frequently encounter

these practices, potentially due to their widespread

adoption in contemporary game monetization strate-

gies. Participants identified patterns like Imperson-

ation less frequently, which may be linked to the low

perceived harmfulness and problematic nature.

Table 3: Ranking of Dark Patterns based on prevalence.

Dark Pattern Prevalence

1. Loot Boxes 100.00%

2. Invested Value 96.70%

3. Endowed Progress 90.00%

4. Grinding 86.70%

5. Pre-delivered 86.70%

6. Pay to Skip 83.30%

7. Pay Wall 83.30%

8. F.O.M.O. 76.70%

9. Appointment 70.00%

10. Social Obligation 53.30%

11. Social Pyramid 53.30%

12. Impersonation 43.30%

13. Monetized Rivalries 40.00%

In the question ‘If yes, in which game?’ partic-

ipants cited specific games where they had encoun-

tered dark patterns. Among the most mentioned were

World of Warcraft (Entertainment, 2004), League of

Legends (Games, 2009), and Genshin Impact (mi-

HoYo, 2020), reflecting their widespread influence in

the gaming community. World of Warcraft was high-

lighted for employing various dark patterns, mainly

Grinding, often tied to its subscription model and

endgame content. League of Legends was noted for

using grinding in ranked play and battle passes. Gen-

shin Impact, known for its gacha mechanics, stood

out as a key example of Grinding and a type of

Loot Boxes, emphasizing the psychological pressure

these systems can exert on players (Xia and Hadden,

2021). These repeated references underscore how

widely recognized dark patterns are in major games,

particularly those with large and diverse player bases.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

478

5.5 Qualitative Analysis of Participant

Comments

Participants frequently expressed difficulty in recog-

nizing the harmfulness of specific dark patterns, es-

pecially when these were integrated seamlessly into

gameplay. For instance, in the case of Grinding, some

participants noted that it often feels like a natural part

of progression rather than an exploitative design. P15

reflected, “Grinding is not necessarily bad; it is only

problematic when progression becomes impossible

without dedicating hours to it.” Similarly, P16 high-

lighted Endowed Progress’s deceptive nature: ”It can

easily lead players to burnout as soon as they reach the

plateau of their level progression.” These comments

underline how dark patterns may go unnoticed until

players experience negative impacts, such as burnout.

A recurring theme in responses was participants’

varying levels of awareness about the manipulative in-

tent behind dark patterns. For example, several com-

ments about F.O.M.O. revealed that it affects players’

psychological state. P25 remarked, “It directly im-

pacts the player’s psychological state negatively, as

it makes them anxious about the possibility of miss-

ing an opportunity.” Likewise, in discussions about

Pay to Skip, P16 acknowledged how casual players or

those with limited time might feel coerced into spend-

ing money, noting, “It is a cheap trick to get quick

cash from players who do not have the time to grind.”

The qualitative responses also highlighted signif-

icant emotional and psychological impacts caused by

dark patterns. P10 described the frustration and ex-

clusion caused by Social Obligation, stating, “It dis-

regards players who have less time to play or are

not particularly inclined toward online socialization.”

Similarly, participants critiqued Loot Boxes for their

gambling-like mechanics, with P16 saying, “It is a

system that exploits players vulnerable to gambling

and probability mechanics to make its monetization

opaque, thereby increasing profits.” These patterns

create emotional pressure and financial harm, empha-

sizing the need for ethic in game design.

6 DISCUSSION

Among the three main categories of Dark Patterns,

the Monetary category emerged as the most harmful,

based on participants’ ratings. Patterns such as Pay

Wall and Pre-Delivered Content consistently ranked

highest in perceived harmfulness and problematic na-

ture. The significant harmfulness of Pay Wall re-

flects participants’ frustrations with being coerced

into spending money to progress in games, which dis-

rupts their sense of autonomy and satisfaction. Like-

wise, Pre-Delivered Content was perceived as highly

harmful due to its deceptive nature, as it locks content

that is already present in the game, creating a sense of

unfair monetization. Similarly, Impersonation drew

polarized reactions, as it manipulates players by mim-

icking relationships or personal relevance, making its

social and emotional impact particularly contentious.

Temporal patterns, such as Grinding, were deemed

less harmful but problematic due to their exploitative

demand for repetitive gameplay. While frustrating,

these patterns were perceived as a standard aspect of

many games rather than deliberate manipulations.

Participants demonstrated a strong ability to iden-

tify and understand dark patterns across most cate-

gories. The clarity ratings of 100% for nearly all pat-

terns suggest that players know the mechanics used

to manipulate them. This is particularly evident in

patterns like Grinding and Playing by Appointment,

which players frequently encounter in games and can

easily recognize. However, six participants reported

difficulties understanding Impersonation’s definition

or example, underscoring the need to better articu-

late its characteristics. This may be related to the low

ranking of Impersonation among the three rankings.

The rankings highlight that players perceive some

patterns as more problematic due to their immediate

impact. For example, Monetary patterns like Pay Wall

harm the player experience and evoke a sense of co-

ercion, making them stand out as particularly egre-

gious. On the other hand, Temporal patterns were

seen as more subtle, often blending into the structure

of games without immediate recognition as harmful.

The frequent mention of World of Warcraft,

League of Legends, and Genshin Impact in par-

ticipant responses highlights how dark patterns are

deeply embedded in some popular games. The promi-

nence of Grinding in both MMORPGs and com-

petitive online games suggests that time-consuming

mechanics are widely accepted but still perceived

as problematic by players. We observed a relation

between perceived harmfulness and problematic na-

ture: patterns that directly exploited players finan-

cially, such as Pay Wall and Loot Boxes, were rated

both highly problematic. In contrast, patterns that

primarily affected players’ time or progression, such

as Grinding and Endowed Progress, were considered

less harmful but disruptive to the gaming experience.

This relation highlights how players recognize imme-

diate financial exploitation as more detrimental than

time-based inconveniences.

These findings underscore the nuanced percep-

tions players hold about dark patterns. While they

recognize the negative aspects of these patterns, their

Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness

479

tolerance or acceptance may vary depending on the

context. For instance, Patterns like Grinding are seen

as a trade-off for extended gameplay, suggesting that

the player’s gaming habits moderate their harmful-

ness. In contrast, Monetary patterns breach ethical

boundaries more clearly, as they directly exploit fi-

nancial commitments, often without offering mean-

ingful in-game benefits. The results also suggest a

growing awareness among players of manipulative

design strategies, which could drive demand for trans-

parency and ethical practices in game design.

7 THREATS TO VALIDITY

This study’s validity assessment follows the frame-

work proposed by Cook and Campbell (1979), en-

compassing threats to conclusion, internal, construct,

and external validity.

Internal validity refers to the ability to ensure

that the observed outcomes are causally related to the

treatment rather than extraneous factors. In this study,

internal validity was bolstered by conducting a pi-

lot test of the survey instrument. The pilot allowed

refinement of unclear definitions and examples, en-

suring that participants fully understood the dark pat-

terns being evaluated. However, potential biases, such

as participant fatigue or differences in interpretation,

may still exist. These were minimized by informing

participants of the estimated time required to com-

plete the survey, providing clear instructions, and en-

suring a concise survey design.

External validity concerns the generalizability of

results to broader populations. A primary limitation

of this study is convenience sampling and a relatively

small sample size (N=30). While this limits the gener-

alization of findings, the sample included participants

with diverse gaming engagement levels, which helps

capture varied perceptions.

Construct validity relates to the alignment be-

tween theoretical constructs and their operationaliza-

tion in the study. To address this threat, the dark pat-

terns catalog was developed systematically using es-

tablished literature and real-world examples sourced

from gaming communities. We refined definitions

and examples iteratively, ensuring they accurately

represented the intended constructs. Additionally, the

final survey included clarity assessments, confirming

that most participants found the definitions under-

standable. Despite these efforts, the pattern Imper-

sonation had a lower clarity rating, indicating room

for further refinement.

Conclusion validity refers to the statistical sound-

ness of the results. This study ensured conclusion va-

lidity through robust statistical testing. The Shapiro-

Wilk test confirmed that data did not follow a normal

distribution, leading to the appropriate use of non-

parametric tests. We provided descriptive statistics to

contextualize the findings and identify outliers, which

were retained to preserve the integrity of the analysis.

8 CONCLUSION

This study presents a catalog of dark patterns in

games. The definitions were derived from previous

research and clarified with practical examples from

actual games. Using a survey administered to 30 par-

ticipants with varying levels of gaming engagement,

we analyzed the perceived harmfulness, problematic

nature, and prevalence of each dark pattern. As a re-

sult, we generated three rankings and discussed the

participants’ feedback on each dark pattern.

The results revealed that Monetary Dark Patterns,

such as Pay Wall and Loot Boxes, were perceived as

the most harmful and highly problematic, reflecting

players’ heightened sensitivity to financial exploita-

tion. In contrast, Temporal Dark Patterns, like Grind-

ing and Endowed Progress, were deemed less harmful

but disruptive to the gaming experience. The relation

between harmfulness and problematic nature under-

scores how different dark patterns affect player enjoy-

ment and well-being in distinct ways. The generated

rankings provide a nuanced perspective on these pat-

terns, highlighting the varied psychological and emo-

tional impacts of financial versus time-based exploita-

tion.

This research extends previous studies by provid-

ing an empirically validated perspective on the harm-

fulness of dark patterns in games. While earlier

work mainly focused on theoretical categorization or

heuristic evaluations, this study adds value by incor-

porating player perceptions into the analysis. Further-

more, the rankings of harmfulness, problematic na-

ture, and prevalence offer a practical framework for

assessing and reducing the use of dark patterns in

games. The findings underscore the importance of

ethical game design practices prioritizing player en-

gagement and well-being.

Future work could expand this research by in-

creasing the sample size, exploring additional pat-

terns, or examining the cultural and demographic fac-

tors influencing perceptions of dark patterns. More-

over, longitudinal studies could provide insights into

how player attitudes toward dark patterns evolve, par-

ticularly in the context of emerging game monetiza-

tion strategies.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

480

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the participants in the empirical study

and USES Research Group members for their sup-

port. The present work is the result of the Research

and Development (R&D) project 001/2020, signed

with Federal University of Amazonas and FAEPI,

Brazil, which has funding from Samsung, using re-

sources from the Informatics Law for the Western

Amazon (Federal Law nº 8.387/1991), and its disclo-

sure is in accordance with article 39 of Decree No.

10.521/2020. Also supported by CAPES – Financing

Code 001, CNPq process 314797/2023-8, CNPq pro-

cess 443934/2023-1, CNPq process 445029/2024-2,

and Amazonas State Research Support Foundation –

FAPEAM – through POSGRAD 24-25.

REFERENCES

Aagaard, M., Meyer, J. J., and Schumacher, S. (2022).

A game of dark patterns: Designing healthy, highly-

engaging mobile games. In Proceedings of the 12th In-

ternational Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for

Serious Applications (VS-Games), pages 34–45. IEEE.

Abyss, P. (2015). Black desert online. PC.

Arkes, H. R. and Blumer, C. (1985). The psychology of

sunk cost. Organizational Behavior and Human Deci-

sion Processes, 35(1):124–140.

Babbie, E. (2014). The Practice of Social Research. Cen-

gage Learning, 14th edition.

Brignull, H. (2010). Dark patterns: Deceptive user inter-

faces. https://darkpatterns.org.

Cook, T. D. and Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-

Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field

Settings. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Dahlan, R. P. and Susanty, M. (2022). Finding dark pat-

terns in casual mobile games using heuristic evaluation.

PETIR: Jurnal Pengkajian dan Penerapan Teknik Infor-

matika, 15(2):185–190.

Dunn, O. J. (1964). Multiple comparisons using rank sums.

Technometrics, 6(3):241–252.

Enix, S. (2010). Final fantasy xiv. PC, PlayStation 3,

PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5.

Entertainment, B. (2004). World of warcraft. http://www.

worldofwarcraft.com.

Flankkum

¨

aki, S. and S

¨

oderholm, E. (2020). How dark pat-

terns affect desirability in candy crush saga. Bachelor

Thesis, J

¨

onk

¨

oping University, School of Engineering.

Gach, E. (2018). China cracks down on loot boxes by forc-

ing companies to disclose odds. Accessed: 2024-06-18.

Games, M. (1992). Mortal kombat. Arcade, PlayStation,

Xbox, PC, and others.

Games, R. (2009). League of legends. http://www.

leagueoflegends.com.

Gray, C. M., Kou, Y., Battles, B., Hoggatt, J., and Toombs,

A. L. (2018). The dark (patterns) side of ux design. Pro-

ceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction,

2(CSCW):1–18.

Greenberg, S. and Pashang, S. (2020). Dark patterns in mo-

bile apps: Understanding how apps use manipulative de-

sign to increase engagement. In Proceedings of the 2020

CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Sys-

tems, pages 1–12. ACM.

Hodent, C. and Others (2024). Ethical concerns in the gam-

ing industry: Safeguarding players and developers. In

Proceedings of the Ethical Games Conference.

Kitchenham, B. A. and Pfleeger, S. L. (2008). Personal

opinion surveys. In Shull, F., Singer, J., and Sjøberg,

D. I. K., editors, Guide to Advanced Empirical Software

Engineering. Springer.

Kruskal, W. H. and Wallis, W. A. (1952). Use of ranks in

one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American

Statistical Association, 47(260):583–621.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of atti-

tudes. Archives of Psychology, 140:1–55.

Mathur, A., Acar, G., Friedman, M., Lucherini, E., Mayer,

J., Chetty, M., and Narayanan, A. (2019). Dark patterns

at scale: Findings from a crawl of 11k shopping web-

sites. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer In-

teraction, 3(CSCW):1–32.

McCoy, T. and Luger, E. (2020). Streaming by default:

Dark patterns in subscription-based media platforms. In

Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Conference on Fairness,

Accountability, and Transparency (FAT* ’20), pages 1–

10. ACM.

miHoYo (2020). Genshin impact. https://genshin.mihoyo.

com.

Shapiro, S. S. and Wilk, M. B. (1965). An analysis of vari-

ance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika,

52(3-4):591–611.

Wohlin, C., Runeson, P., H

¨

ost, M., Ohlsson, M. C., Regnell,

B., and Wessl

´

en, A. (2012). Experimentation in Software

Engineering. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Xia, H. and Hadden, D. (2021). Gacha mechanics in Gen-

shin Impact: A study of player motivation and spend-

ing behavior. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds,

13(2):123–142.

Zagal, J. P., Bj

¨

ork, S., and Lewis, C. (2013). Dark patterns

in the design of games. In Proceedings of the 8th Interna-

tional Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games

(FDG), pages 1–8. ACM.

Dark Patterns in Games: An Empirical Study of Their Harmfulness

481