Optimizing Morphological Design in High-Density Residences in

Hong Kong to Enhance Mental Health

Zijun Wang

School of Landscape Architecture, Beijing Forestry University, China

Keyword: High-Density Urban Living, Mental Well-Being, Urban Morphology, Visual Exposure, Thermal Comfort,

Wallacei Optimization.

Abstract: This study addresses the challenges of enhancing mental well-being in high-density residential environments,

with a specific focus on Hong Kong. Employing a 3D model in Rhino and parametric design in Grasshopper,

we used the Wallacei plugin for multi-objective optimization to balance four critical factors—visual exposure,

direct sun hours, Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) standard deviation, and building volume—across

four building typologies: East-West oriented dot-and-row forms, North-South oriented dot-and-row forms,

crossing layouts, and loop-shaped layouts. This process generated six locally optimal configurations for each

typology. We then examined how variations in building morphology and street configurations influenced

these factors and, in turn, emotional responses. The results indicate that wider streets and a greater number of

street intersections enhance visual emotional impact, while narrower streets yield a lower UTCI standard

deviation, thereby improving thermal comfort. Typological differences underscore the need for context-

specific design strategies to balance these factors. Our findings provide insights for optimizing building

configurations to promote emotional well-being in high-density urban settings.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Context

High-density urban living, especially in cities such as

Hong Kong, poses unique challenges to mental well-

being owing to limited open spaces, extreme urban

density, and various environmental stressors. (Wong

et al., 2016).

A growing body of research has examined the

relationship between urban environmental factors—

such as visual exposure, greenery, and thermal

comfort—and mental health. Building on this

foundation, the present study explores the specific

impact of building typologies and morphology on

mental well-being in high-density environments.

1.2 Research Gap

Although prior studies have examined the influence

of urban morphology on microclimates and energy

efficiency, there is a paucity of research on using

morphological designs to balance key factors—such

as visual exposure, sunlight exposure, thermal

comfort, and residential density—relative to mental

health in high-density residential areas.

1.3 Research Aim

The primary aim of this research is to use parametric

modeling to control building morphologies and street

configurations, evaluating the combined impact of

different morphologies across various typologies on

visual and thermal exposure—factors that directly

affect environmental comfort.

The ultimate goal is to enhance mental health in

high-density urban settings.

1.4 Framework

The framework of the study is as follows: after the

introduction, the second section will provide a

literature review covering four key areas relevant to

the study. The methodology follows, consisting of

three steps: parametric modeling, environmental

simulation, and multi-objective optimization.

In the parametric modeling step, four building

typologies will be parameterized. The primary

decision variables that influence these typologies will

114

Wang, Z.

Optimizing Morphological Design in High-Density Residences in Hong Kong to Enhance Mental Health.

DOI: 10.5220/0013341600003953

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2025), pages 114-121

ISBN: 978-989-758-751-1; ISSN: 2184-4968

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

be defined, and relevant constraints—such as

dimensional limits and design features—will be

identified for each variable.

For environmental indicators simulation and

quantification, the Isovist plugin in Grasshopper will

first be used to generate five visual exposure metrics

for each layout, while Ladybug will be employed to

calculate thermal metrics. Basic operations will also

be performed to determine the overall volume.

Notably, a mathematical model will establish the

relationship between visual metrics and visual

emotional value, while thermal metrics and volume

will serve as direct optimization objectives.

The key step, multi-objective optimization, will

utilize the Wallacei multi-objective optimization tool,

incorporating the NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting

Genetic Algorithm II). This tool will balance

environmental indicators and identify configurations

that maximize positive mental health outcomes.

Simulations will be conducted for each building

typology, yielding six representative locally optimal

solutions per typology. A post-hoc analysis will then

be performed on these solutions within each building

type, uncovering consistent findings.

Last by not

least, a conceptual approach to exploring the

improvement saturation effect will be proposed,

which could be used for further investigation in the

future.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Mental Health and Urban Density

Urban living and city-based upbringing affect human

neural responses to social stress. (Lederbogen et al.,

2011). Crowding, noise, and prolonged exposure to

dense environments further exacerbate stress and

anxiety (Tost et al., 2015).

Urban planning increasingly focuses on

enhancing visual and thermal comfort to mitigate

these stressors (Liu et al., 2024).Urban parks, for

example, enhance visual openness and regulate local

climates in dense settings (Chiesura, 2004), while

abundant greenery aids stress recovery (Ulrich et al.,

1991) and improves overall emotional well-being

(Xiang et al., 2021), particularly benefiting older

adults (Luo et al., 2024). These findings align with the

concept of “affective atmospheres,” which suggests

that urban green spaces optimized for visual and

thermal comfort can effectively reduce stress (Deitz

et al., 2018).

However, integrating green spaces often conflicts

with the demand for additional living areas in high-

density cities, such as Hong Kong. This trade-off

necessitates alternative strategies, such as optimizing

building morphologies and street layouts.

2.2 Visual Exposure and Emotion

Visual exposure plays a key role in emotional well-

being in dense urban environments.

Visual openness has been shown to reduce stress

(Stamps, 2005), while individuals' perceptions of it

significantly shape emotional responses (Yang et al.,

2024). In addition, building forms influence visibility

in crowded settings (Giseop et al., 2019); specifically,

moderate building heights, combined with visible

green spaces, enhance emotional comfort (Lindal et

al., 2013). Together, these findings highlight the

importance of designing urban spaces that enhance

visibility to promote mental well-being.

2.3 Thermal Comfort and Emotion

Thermal comfort is critical for mental well-being,

particularly in densely populated areas with limited

climate control.

Specifically, open spaces and vegetation help

improve thermal comfort by reducing the urban heat

island effect (Wang et al., 2021), which in turn

positively influences both physical and emotional

well-being (Yan et al., 2023). Moreover, the

configuration of streets and buildings is essential for

thermal comfort: narrower streets and taller buildings

provide shading that reduces direct sun exposure

(Wang et al., 2023), while layouts that minimize

temperature fluctuations further enhance comfort (Xu

et al., 2019)

2.4 Quantification and Optimization

To optimize urban design for mental well-being, tools

such as Rhino and Grasshopper, along with plug-ins

like IsoVist, Ladybug, and Wallacei, are invaluable

for balancing visual and thermal comfort in high-

density settings.

IsoVist expands visibility analysis by capturing

three-dimensional spatial relationships, helping to

evaluate how building heights and layouts influence

accessibility and psychological comfort. Originally

developed for 2D analysis (Benedikt, 1979) and later

enhanced for 3D relationships, IsoVist is now a key

tool in assessing emotional well-being (Giseop et al.,

2019).

Ladybug supports climate-based simulations to

assess thermal comfort and sunlight exposure across

urban layouts, allowing urban designers to refine their

Optimizing Morphological Design in High-Density Residences in Hong Kong to Enhance Mental Health

115

designs for improved environmental comfort (Wang

et al., 2023).

Wallacei, a genetic algorithm, facilitates multi-

objective optimization to enhance spatial efficiency

(Xu et al., 2019). In our study, it plays a crucial role

in balancing visual exposure, thermal comfort, and

urban density in high-density urban environments.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Site Selection

The experimental site is located in To Kwa Wan,

Hong Kong, within a residential zone.

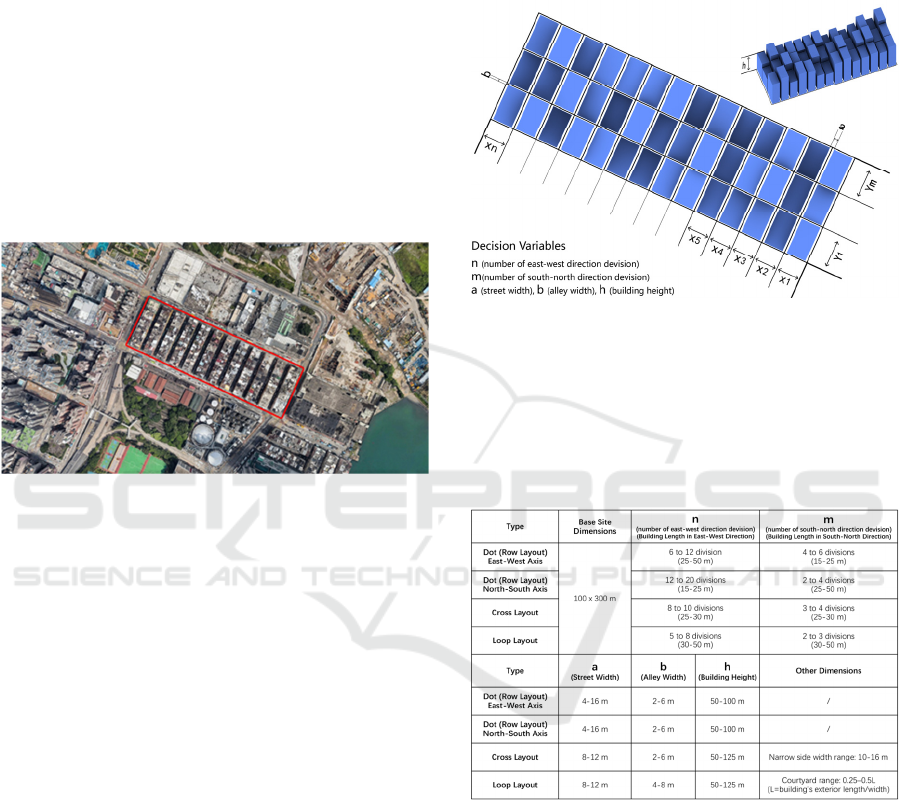

Figure 1: Site location.

Chosen for its redevelopment potential, the area

features low-density buildings with large footprints

that may be replaced by higher-density developments

to improve housing capacity and environment. The

site’s layout comprises regular residential buildings

arranged in long, parallel rows along narrow streets

and alleys, typical of older urban districts in Hong

Kong. With a low floor area ratio (FAR), extensive

ground coverage, and minimal building height

variation, the area provides an ideal setting for testing

different building typologies and exploring how high-

density redesigns can optimize visual exposure,

thermal comfort, and living space to enhance

residents’ emotional well-being. The site location is

shown in Figure 1.

3.2 Parametric Modeling

Hong Kong’s high-density urban environment is

characterized by four typical building typologies:

East-West oriented dot-and-row forms, North-South

oriented dot-and-row forms, crossing layouts, and

loop-shaped layouts. To explore their design

potential, these typologies were parameterized and

simplified for testing. Figure 2 provides an example

of the East-West oriented dot-and-row form, with key

variables involved in parametric modeling including

n (number of divisions along the east-west direction),

m (number of divisions along the north-south

direction), a (street width), b (alley width), and h

(building height).

Figure 2: Five decision variables.

These five variables serve as the decision

variables for the multi-objective optimization. The

parameter constraints for these variables were derived

from map distance calculations in Hong Kong and

supported by relevant architectural research. The

dimensional details are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Parameter constraints.

3.3 Visual Exposure Metrics

Visual exposure was analyzed using the IsoVist plug-

in in Grasshopper, enabling both 2D and 3D isovist

calculations to simulate visibility across the

experimental site. The goal was to understand how

different building forms, along with variations in

street and alley dimensions, affect the visual

experience of residents in a high-density setting.

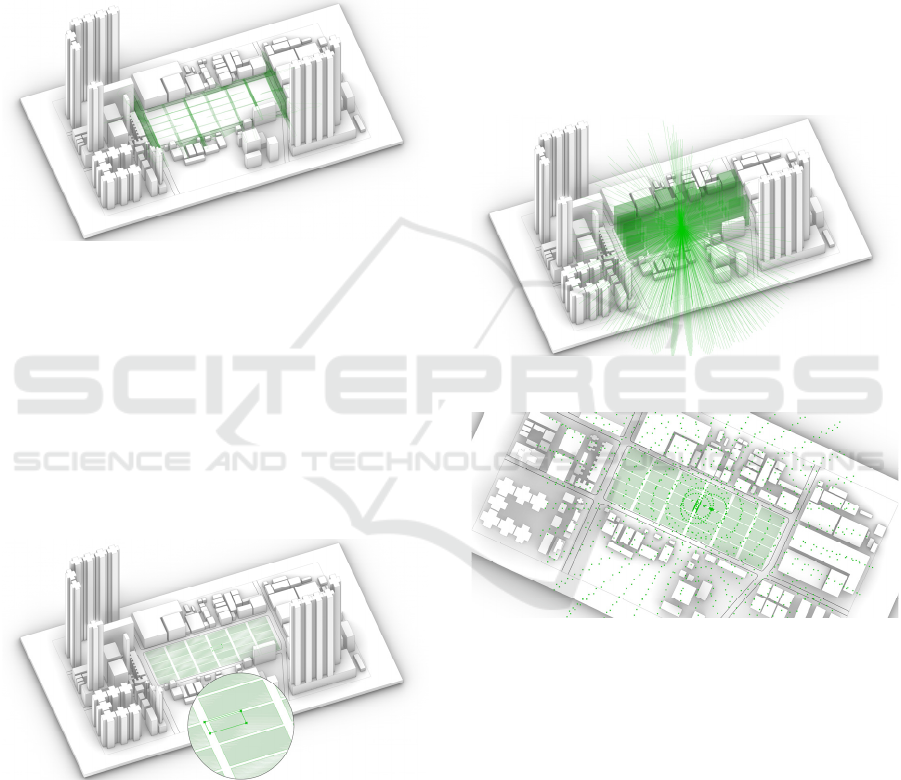

2D Isovist Calculations: The 2D analysis involved

placing observation points uniformly across the site,

SMARTGREENS 2025 - 14th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

116

excluding building interiors to focus solely on the

external visual experience. This approach ensured

comprehensive coverage of the experimental area,

enabling the calculation of average visibility in terms

of ground-level access to streets and open spaces.

Using the IsoVist 2D tool, three key metrics—drift

magnitude, mean radial, and compactness—were

generated to support the subsequent Emotional Value

Calculation. The results of the 2D Isovist calculations

are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: 2D Isovist Calculations

3D Isovist Calculations: For the 3D spatial

analysis, four key observation points were selected to

capture diverse visibility perspectives within the

dense residential layout. In high-density areas with

tall, closely packed buildings, street-level visibility is

often limited to nearby structures; therefore, the four

central points are representative of most viewing

angles. This strategy ensures a balanced assessment

while optimizing computational efficiency. The four

observation points are shown in the figure 5.

Figure 5: Four observation points for 3D.

The four points include: street-alley intersection,

street midpoint, alley midpoint and building center.

When the building layout changes, the street–alley

intersection point can be replaced with the midpoint

of the building's interior. This adjustment ensures that

observation points remain consistent and adaptable,

as both serve as diagonal anchors within a rectangular

layout, preserving their role throughout the analysis.

For each layout type, the 3D visual exposure score is

calculated as the average of the values from all four

observation points, regardless of building type. This

approach ensures a consistent basis for comparing

different layouts. For loop-shaped layouts with

courtyards, the interior point adds a unique visibility

perspective, enabling an evaluation of how the

courtyard influences overall visibility compared to

layouts with more restricted internal sightlines.

Building on this, 3D Isovist analysis calculates

two supplementary metrics—3D object proportion

and 3D visual volume—to further quantify visibility.

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the 3D IsoVist visibility

and effective collision points.

Figure 6: 3D IsoVist visibility.

Figure 7: Effective collision points.

The emotional value, derived from these visibility

parameters, was calculated using an existing Multiple

Linear Regression (MLR) model developed by Xiang

et al. This model estimates emotional responses to

visual exposure by linking isovist parameters to

psychological comfort based on environmental

psychology studies. The MLR coefficients for each

parameter were applied to compute the overall visual

comfort score.

Y=1/n

∑

(0.528a

i

-0.178b

i

+0.29c

i

-0.304d

i

+0.461e

i

)

n: total number of observation points randomly placed on

the site, a: drift magnitude, b: mean radial, c: compactness,

d: 3d object proportion, e: 3d visual volume

Optimizing Morphological Design in High-Density Residences in Hong Kong to Enhance Mental Health

117

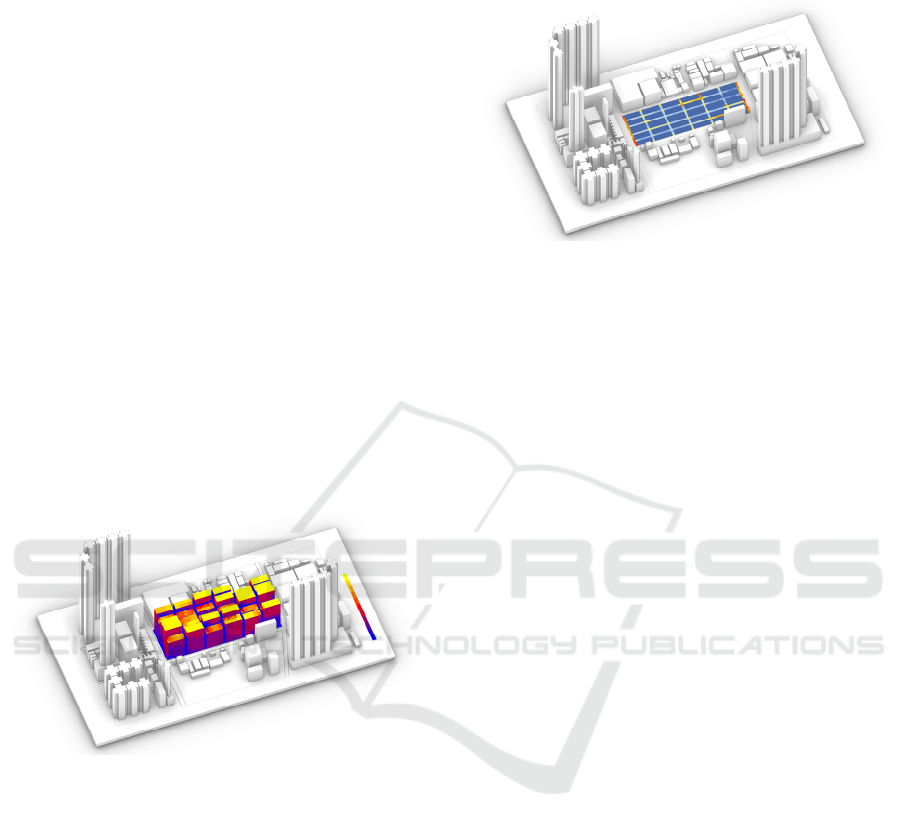

3.4 Thermal Comfort Metrics

Thermal comfort was assessed using two primary

metrics: direct sunlight hours and the standard

deviation of UTCI (Universal Thermal Climate

Index). These metrics help quantify residents' thermal

comfort in relation to the built environment and

weather conditions, particularly important in a hot

climate like Hong Kong.

Direct Sunlight Hours: The Ladybug plug-in in

Grasshopper was used to simulate direct sunlight

exposure on the site, incorporating the experimental

buildings, surrounding structures, and local climate

conditions. The simulation accounted for building

heights and orientations (East-West and North-South)

to estimate sunlight exposure for both the buildings

and the streets. The site was divided into a 10-meter

grid to balance precision with computational

efficiency. By including outdoor spaces alongside

building facades, the analysis aimed to capture thermal

comfort across the entire neighborhood. The focus was

on minimizing excessive sunlight exposure, which can

significantly reduce thermal comfort in hot climates.

Figures 8 illustrates the direct sunlight hours.

Figure 8: Direct Sunlight Hours.

UTCI Standard Deviation: The Universal Thermal

Climate Index (UTCI) measures thermal comfort by

accounting for factors like air temperature, humidity,

and wind speed. In this study, the standard deviation

of UTCI values was used to evaluate temperature

variability across the site, prioritizing spatial

consistency over average UTCI. Using the Ladybug

plug-in in Grasshopper, the site was divided into a 5-

meter grid, with UTCI values calculated for each grid

cell to capture localized temperature variations in

outdoor areas. This approach enabled a detailed

analysis of how design elements—such as building

dimensions, orientation, and spacing—affect thermal

stability. Examining UTCI standard deviation helped

identify areas prone to sudden temperature changes,

offering insights into how design adjustments can

promote stable outdoor thermal comfort. Figures 9

illustrates the UTCI standard deviation.

Figure 9: UTCI Standard Deviation.

3.5 Building Volume

The total building volume was calculated to reflect the

density and massing of the proposed morphologies.

As density is critical in urban planning, this metric

was essential for balancing high-density residential

needs with emotional well-being. Building volume

for each morphology was determined based on height,

footprint, and spatial configuration, ensuring that the

designs met density requirements.

3.6 Optimization with Wallacei

Metrics for visual exposure, thermal comfort (direct

sunlight and UTCI deviation), and building volume

were calculated and optimized using the Wallacei

plug-in. This tool employed a genetic algorithm to

balance competing factors—visual access, thermal

comfort, and building density—across four building

typologies. The optimization process aimed to

maximize visual exposure, minimize excessive

sunlight, maintain stable thermal comfort, and

achieve higher density.

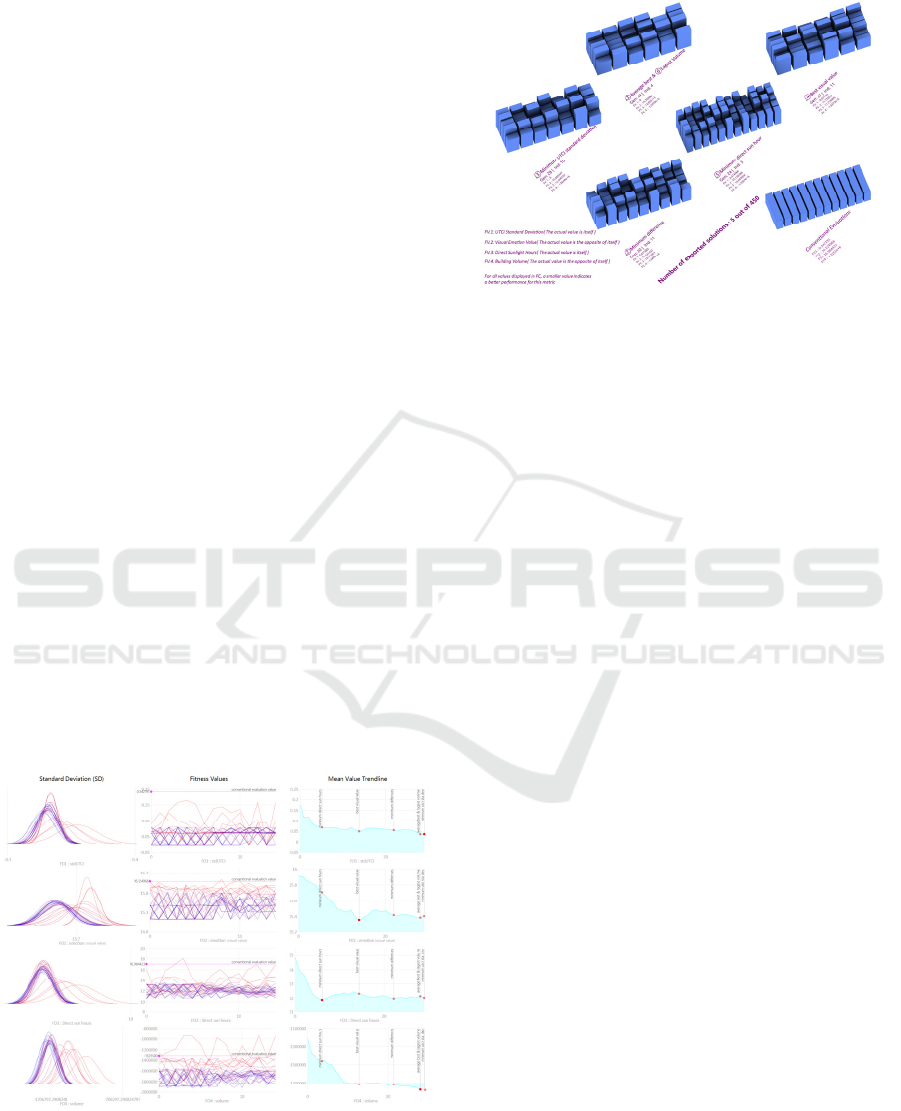

4 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

4.1 Overview

Using Wallacei X, which integrates the built-in

genetic algorithm with NSGA-II (Non-dominated

Sorting Genetic Algorithm II), each of the four

typologies underwent 15 generations, with 30

individuals per generation.

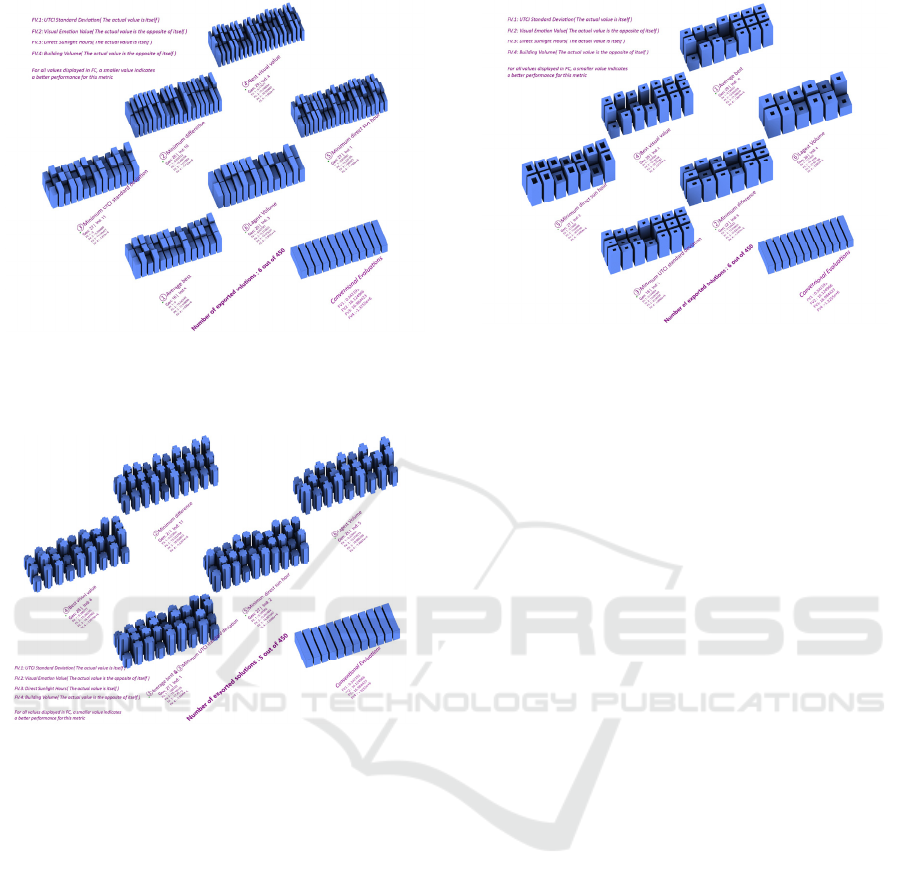

Taking the East-West Oriented Dot and Row form

as an example (Figure 10), the first column illustrates

the evolution of the curve from red (initial

generations) to blue (subsequent generations), while

SMARTGREENS 2025 - 14th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

118

the left-to-right progression indicates progressively

better results.

The second column shows the changes in the

values of each optimization objective, where the

values decrease from red to blue, reflecting improved

optimization outcomes. The conventional evaluation

values are also annotated on the graph, demonstrating

that the majority of optimized results are lower than

the initial values, thus validating the effectiveness of

the optimization.

The third column depicts the trend of the objective

variables across generations, showing a gradual

reduction, which further supports the success of the

optimization process. Additionally, it also highlights

the specific values of six outstanding individuals and

the time they first appear.

Similarly, the other three typologies were also

optimized, and six local optimal individuals were

selected for each typology, including the Average

Best, Minimum Difference, and the local optima for

the four key criteria (Minimum UTCI Std. Dev., best

visual emotion value, minimum direct sun hours, and

largest volume). After obtaining the final shapes of

the selected individuals, a preliminary analysis was

conducted to explore the relationship between the

individual shapes and the four indicators.

This analysis examined the impact of street (alley)

width and number on visual exposure, UTCI standard

deviation, and direct sunlight hours, as well as the

influence of typology-specific differences on these

factors. Additionally, the conventional building

shapes and the corresponding evaluation values were

also presented across all four groups of results to

further validate the reliability of the optimization

outcomes.

Note: The lower the value shown in the image, the better the

corresponding indicator. The value of building volume should

be converted to a positive number for practical use.

Figure 10: Result of the Wallacei genetic algorithm.

4.2 East-West Oriented Dot and Row

Figure 11: Local Optimal Solutions (Type 1).

Street Width Impact: Comparing configurations ①

and ④, we find that with the same number of streets

and alleys, wider streets improve the visual emotion

value (p<0.05).

Number of Streets and Alleys: With consistent

street width (①, ②, ③, ⑤), an increase in street

count enhances the visual emotion value, indicating

that a higher street density may promote emotional

well-being.

Sunlight and UTCI: Consistent street width (①,

②, ③, ⑤) shows that more streets correlate with

longer minimum direct sun hours, impacting thermal

comfort. However, the effect on UTCI Std. Dev. is

inconsistent.

Building Dimensions: With the same number of

streets and alleys ( ① vs. ④ ), larger buildings

mitigate direct sun exposure but increase UTCI Std.

Dev.

All optimized results for the four indicators are

below the conventional values, demonstrating the

effectiveness of the optimization.

4.3 North-South Oriented Dot and Row

Street Width and Emotion Value: Similar to East-

West forms, wider streets (④ vs. ⑤) enhance visual

emotion value.

Street Count and Emotion Value: With consistent

alley width, more streets increase visual emotion

value, suggesting a positive relationship between

urban density and emotional well-being.

Contradiction in UTCI: The negative effect of

street width on UTCI Std. Dev. contradicts the

findings from Experiment 1, highlighting the need for

further investigation into this discrepancy.

Optimizing Morphological Design in High-Density Residences in Hong Kong to Enhance Mental Health

119

Figure 12: Local Optimal Solutions (Type 2).

4.4 Crossing Layouts

Figure 13: Local Optimal Solutions (Type 3).

Street Width and Visual Emotion: Wider streets (①

vs. ④) improve visual emotion value, aligning with

other layouts.

Street Count and Thermal Comfort: Increasing

street count with consistent width improves direct sun

exposure but has an inconsistent impact on UTCI Std.

Dev.

Building Dimensions As observed in other

layouts, larger buildings mitigate direct sun exposure

but increase UTCI Std. Dev.

4.5 Loop-Shaped Layouts

Street Width and Emotion Value: Wider streets (①

vs. ④) enhance visual emotion value.

Street Count and UTCI: An increase in street

count positively affects UTCI Std. Dev., which

contrasts with findings from other experiments,

indicating a complex relationship.

Figure 14: Local Optimal Solution (Type 4).

Atrium Scale Impact: Atrium scale has a more

significant positive impact on visual emotion value

than street count, suggesting the importance of open

spaces in dense urban areas.

5 DISCUSSIONS

By comparing the six locally optimal solutions for

each of the four building typologies, a clear pattern

emerged: wider streets and higher street counts

enhance visual emotion values, while narrower streets

help stabilize UTCI Std. Dev., improving thermal

comfort. Typology-specific differences were also

noted. For example, loop-shaped layouts with atriums

had a greater positive impact on visual emotion value

than street count. These findings highlight the

importance of adjusting designs for individual

typologies while adhering to broader principles.

However, the results were validated only within a

limited sample. To explore the potential thresholds of

influence—such as when changes in decision

variables lead to saturation—we propose further

investigation. Wallacei genetic algorithm propagates

optimal offspring, meaning that decision variables

favorable to the objectives appear more frequently,

concentrating high-quality solutions. We plan to

analyze the optimization data to track variable

frequencies. Preliminary analysis offers three key

thresholds for further investigation: at what street

widths and intersection counts do visual value

improvements saturate, and at what widths does

thermal comfort reach saturation? Given Wallacei's

discrete selection method, we propose reclassifying

street widths into smaller intervals (e.g., 0.5 meters)

from 4 meters to 16 meters, resulting in 24 intervals.

This approach will help track and compare the

SMARTGREENS 2025 - 14th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

120

frequency of intervals, improving accuracy in

identifying the ranges where saturation effects occur.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study explored how optimizing building

morphologies and street configurations improves

mental well-being in high-density areas by balancing

visual exposure, thermal comfort, and urban density.

However, the study has limitations. The small dataset

may limit generalizability, and the emotional value

model (MLR) may not fully reflect local conditions.

Additionally, the simplified parametric models and

focus on Hong Kong may reduce applicability to other

regions. Future research could address these

limitations by exploring growth thresholds,

expanding the dataset, refining the emotional value

model, and incorporating more detailed urban

representations to validate and extend the findings.

REFERENCES

Wong, C. S. M., Chan, W. C. (2016). Living Environment

and Psychological Distress in the General Population of

Hong Kong. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 36, 78-

81. ISSN 1878-0296.

Lederbogen, F., Kirsch, P., Haddad, L. (2011). City living

and urban upbringing affect neural social stress

processing in humans. Nature, 474, 498–501.

Tost, H., Champagne, F. A., Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2015).

Environmental influence in the brain, human welfare

and mental health. Nat Neurosci, 18(10), 1421-1431.

Liu, Z., Liu, C. (2024). The association between urban

density and multiple health risks based on interpretable

machine learning: A study of American urban

communities. Cities, 153, 105170. ISSN 0264-2751.

Chiesura, A. (2004). The role of urban parks for the

sustainable city. Landscape and Urban Planning, 68(1),

129-138. ISSN 0169-2046.

Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles,

M. A., Zelson, M. (1991). Stress recovery during

exposure to natural and urban environments. Journal of

Environmental Psychology, 11(3), 201-230. ISSN

0272-4944.

Xiang, L., Cai, M., Ren, C., Ng, E. (2021). Modeling

pedestrian emotion in high-density cities using visual

exposure and machine learning: Tracking real-time

physiology and psychology in Hong Kong. Building

and Environment, 205, 108273. ISSN 0360-1323.

Luo, W., Chen, C., Li, H., Hou, Y. (2024). How do

residential open spaces influence the older adults’

emotions: A field experiment using wearable sensors.

Landscape and Urban Planning, 251, 105152.

Deitz, M., Notley, T., Catanzaro, M., Third, A., Sandbach,

K. (2018). Emotion mapping: Using participatory

media to support young people's participation in urban

design. Emotion, Space and Society, 28, 9-17.

Stamps, A. E. (2005). Isovists, Enclosure, and Permeability

Theory. Environment and Planning B: Planning and

Design, 32(5), 735-762.

Yang, S., Dane, G., van den Berg, P., Arentze, T. (2024).

Influences of cognitive appraisal and individual

characteristics on citizens’ perception and emotion in

urban environment: model development and virtual

reality experiment. Journal of Environmental

Psychology, 96, 102309.

Giseop, K. I. M., Ayoung, K. I. M., Youngchul, K. I. M.

(2019). A new 3D space syntax metric based on 3D

isovist capture in urban space using remote sensing

technology. Computers, Environment and Urban

Systems, 74, 74-87.

Lindal, L. P. J., Hartig, T. (2013). Architectural variation,

building height, and the restorative quality of urban

residential streetscapes. Journal of Environmental

Psychology, 33, 26-36. ISSN 0272-4944.

Wang, W., Liu, K., Zhang, M., Shen, Y., Jing, R., Xu, X.

(2021). From simulation to data-driven approach: A

framework of integrating urban morphology to low-

energy urban design. Renewable Energy, 179, 2016-

2035. ISSN 0960-1481.

Yan, T., Jin, H., Jin, Y. (2023). The mediating role of

emotion in the effects of landscape elements on thermal

comfort: A laboratory study. Building and

Environment, 233, 110130.

Wang, J., Liu, W., Sha, C., Zhang, W., Liu, Z., Wang, Z.,

Du, X. (2023). Evaluation of the impact of urban

morphology on commercial building carbon emissions

at the block scale – A study of commercial buildings in

Beijing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 408, 137191.

ISSN 0959-6526.

Xu, X., Yin, C., Wang, W., Xu, N., Hong, T., Li, Q. (2019).

Revealing Urban Morphology and Outdoor Comfort

through Genetic Algorithm-Driven Urban Block

Design in Dry and Hot Regions of China. Sustainability,

11(13), 3683.

Benedikt, M. L. (1979). To take hold of space: Isovists and

isovist fields. Environment and Planning B: Planning

and Design, 6(1), 47-65.

Optimizing Morphological Design in High-Density Residences in Hong Kong to Enhance Mental Health

121