Large Language Model-Informed Geometric Trajectory Embedding for

Driving Scenario Retrieval

Tin Stribor Sohn

1,∗

, Maximilian Dillitzer

1,2,∗

, Tim Br

¨

uhl

1

, Robin Schwager

1

,

Tim Dieter Eberhardt

1

, Michael Auerbach

2

and Eric Sax

3

1

Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG, Weissach, Germany

2

Hochschule Esslingen, Esslingen, Germany

3

Karlsruher Institut f

¨

ur Technologie, Karlsruhe, Germany

Keywords:

Geometric Trajectory Embedding, Large Language Model, Scenario Retrieval, Behavioural Scenario.

Abstract:

This paper introduces a Large Language Model-informed geometric embedding for retrieving behavioural

driving scenarios from unlabelled trajectory data, aimed at improving the search of real driving data for

scenario-based testing. A Variational Recurrent Autoencoder with a Hausdorff Distance-based loss generates

trajectory embeddings that capture detailed spatial patterns and interactions, offering enhanced interpretability

over traditional mean squared error-based models. The embeddings are further organised through unsuper-

vised clustering using HDBSCAN, grouping scenarios by similarities at the scene, infrastructure, behaviour,

and interaction levels. Using GPT-4o for describing scenarios, clusters, and inter-cluster relationships, the

approach enables targeted scenario retrieval via a Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation pipeline, enabling a

natural language search of unlabelled trajectories. Evaluation demonstrates a retrieval precision of 80.2% for

behavioural queries involving infrastructure, multi-agent interactions, and diverse traffic conditions.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Safety of the Intended Functionality (SOTIF)

standard provides guidance for the validation and ver-

ification (V&V) process of automated driving systems

(ADS). According to SOTIF, driving functions must

not only ensure safety under typical operating condi-

tions, but must also be able to deal with hazardous

and unforeseen scenarios that pose the highest safety

risks (International Organization for Standardization,

2022). This standard emphasises the need for an ADS

not only to behave safely on its own, but also to antic-

ipate and handle potential faults and misbehaviour of

other road users, emphasising that driving functions

need to be evaluated at a behavioural level to ensure

robust fault anticipation.

In real-world driving data, road user behaviour is

often represented by object lists with associated tra-

jectories that serve as indicators of driving scenar-

ios. However, mapping scenarios and their associ-

ated trajectories to each other remains a significant

challenge for V&V tasks. Existing manoeuvre-based

∗

Equal contribution

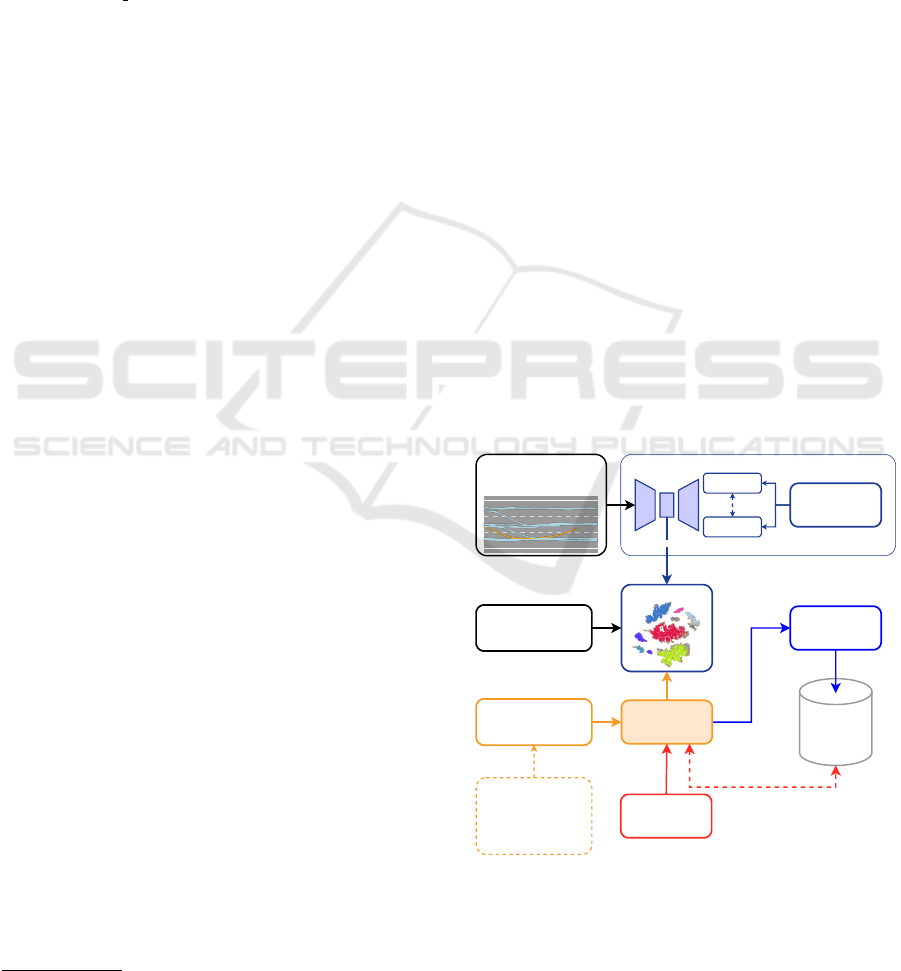

Ego Trajectory

& Trajectories of other

Road Users

VRAE

Latent Space

Geometric Embedding

LLM

Trajectory and Cluster

Description with

Prompts

Cluster Embedding

(HDBSCAN)

GraphRAG

Indexing

Graph

Database

Natural Language

Query

queried Output

Reconstructed

Ground Truth

Hausdorff

Distance

1. Describe Sample Scene

2. Compare to neighbouring

Samples in same Cluster

3. Compare to random

Samples of other Clusters

Figure 1: Method for generating geometric trajectory em-

beddings and mapping them to textual descriptions, en-

abling scenario retrieval and searchability at a behavioural

level through natural language queries.

approaches often rely on pre-defined rules, which

66

Sohn, T. S., Dillitzer, M., Brühl, T., Schwager, R., Eberhardt, T. D., Auerbach, M. and Sax, E.

Large Language Model-Informed Geometric Trajectory Embedding for Driving Scenario Retrieval.

DOI: 10.5220/0013276500003941

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems (VEHITS 2025), pages 66-75

ISBN: 978-989-758-745-0; ISSN: 2184-495X

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

may not be sufficient to capture the full range of be-

havioural complexity.

This paper proposes a novel method to enhance

the searchability of unlabelled trajectory-based sce-

narios found in naturalistic driving data through the

integration of geometric trajectory embeddings and

Large Language Models (LLMs) (Fig. 1). By ad-

dressing existing limitations in the searchability of be-

havioural scenarios in scenario-based testing (SBT),

the proposed method contributes to the state of the art

in five key ways:

• Fine-Grained Clustering of Unlabelled Trajec-

tories: Using a variational recurrent autoencoder

and a Hausdorff loss function, geometric embed-

dings are generated for unlabelled trajectories that

capture fine-grained attributes rather than aver-

age metrics such as mean squared error (MSE).

Cluster analysis within this embedding space is

achieved by Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial

Clustering of Applications with Noise (HDB-

SCAN) to reveal attribute patterns.

• Integrated Embedding of Scene Elements and

Interactions: The joint geometric embedding en-

compasses infrastructure, general scene context,

manoeuvres, and object interactions, reflecting

multi-object scenarios.

• Behavioural Scenario Description and Search-

ability: By describing and comparing trajec-

tory clusters in the geometric embedding through

prompting an LLM for natural language descrip-

tions (Wei et al., 2022), the method improves in-

terpretability and enables behaviour-based search-

ability across clusters, allowing natural language

queries to be mapped to trajectory data.

• Indexing Through the GraphRAG Pipeline:

Embeddings are indexed within a Graph

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipeline

(Edge et al., 2024), enabling natural language re-

trieval and open vocabulary manoeuvre mapping,

along with combinatorial behaviour scenario

search.

• Demonstrated Retrieval Performance: Evalua-

tion results indicate an average retrieval precision

of 80.2% with promising results in scenarios re-

trieval involving infrastructure and object interac-

tions, as well as in the combinatorial manoeuvre

space.

2 RELATED WORK

Current behavioural scenario extraction methods can

be classified into learning-based embeddings, trajec-

tory clustering and rule-based manoeuvre extraction.

Learning-based trajectory embedding approaches

use deep learning techniques to generate embeddings

of driving scenarios.

Sonntag et al. introduced a method to minimise

the test space by identifying edge cases using deep

learning based outlier detection (Sonntag. et al.,

2024). Their approach used autoencoders to gener-

ate trajectory embeddings and calculated MSE recon-

struction errors to identify unusual scenarios. How-

ever, this method has limitations as it focuses primar-

ily on spatio-temporal features and relies on an overall

scenario embedding, which limits its applicability for

detailed scenario analysis, particularly when address-

ing SOTIF. The use of MSE often fails to preserve

the finer geometric properties of the trajectories, re-

sulting in a more generalised representation that may

miss critical behavioural nuances such as local lateral

driving behaviour. In addition, the interpretability and

searchability of the embedding is challenging as the

properties of the clusters are not described.

Hoseini et al. present a non-parametric trajectory

clustering framework using Generative Adversarial

Networks (GANs) to generate realistic synthetic data

(Hoseini et al., 2021). Their approach incorporates

geometric relations through Dynamic Time Warping

(DTW) and models transitive relations within an em-

bedding space. However, its applicability to be-

havioural scenario search is limited due to the limited

interpretability of the embedding space. Furthermore,

it only considers lateral and longitudinal positioning,

omitting key parameters essential for dynamic sce-

nario characterisation, and focuses on only three spe-

cific scenarios: cut-in and left or right pass-by ma-

noeuvres.

Clustering-based methods have also been ex-

plored to group similar driving scenarios, often focus-

ing on the temporal and dynamic aspects of trajecto-

ries.

Ries et al. introduced a method for trajectory-

based clustering using DTW, which identifies similar

driving scenarios by comparing the temporal align-

ment of dynamic object trajectories (Ries et al., 2021).

While this method is effective for querying similar

trajectories, it does not capture the full complexity of

driving scenarios, particularly in terms of abstraction

layers that involve multiple interacting entities and re-

lated infrastructure.

Similarly, Watanabe et al. proposed a sce-

nario clustering method based on predefined features

(Watanabe et al., 2019). Although this approach al-

lows for the organisation of scenario data, it lacks the

ability to adaptively discover relevant features from

the trajectory data itself, limiting its applicability to

Large Language Model-Informed Geometric Trajectory Embedding for Driving Scenario Retrieval

67

behavioural scenario search.

Rule-based manoeuvre extraction approaches for

driving scenario retrieval are based on pre-defined

rules and patterns.

Montanari et al. introduced a pattern cluster-

ing method that identifies recurring scenario patterns

from time series data (Montanari et al., 2020). While

this method is useful for recognising common scenar-

ios and corner cases, it does not explicitly consider

the geometric properties of the trajectories in relation

to the infrastructure and lacks interpretability due to

missing pattern descriptions.

Elspas et al. introduced a more sophisticated

rule-based system using regular expressions to extract

driving scenarios (Elspas et al., 2020). Their method

focuses on detecting specific manoeuvres, such as

cut-ins and lane changes, by applying pre-defined

rules to time series data. While this allows for a

functional interpretation of scenario patterns, the rule-

based nature of the system requires significant manual

effort to define appropriate patterns, which limits its

scalability and adaptability to new scenarios, and may

also lead to missing specifications of certain edge and

corner cases.

Later, Elspas et al. used fully Convolutional Neu-

ral Networks (CNNs) to extract scenarios from time

series data (Elspas et al., 2021). However, their ap-

proach relies on labelled datasets with ground truth

annotations, which presents challenges in terms of

complexity and scalability, as manually annotating

large and diverse datasets is labour intensive and

may not cover all relevant aspects of real-world be-

havioural driving scenarios.

Sohn et al. investigated natural language sce-

nario retrieval, assessing the ability of different LLMs

to capture scenario information (Sohn et al., 2024).

However, as this work focused on the description and

retrieval of perceptual data within the 6-Layer Model

(6LM) framework (Scholtes et al., 2021), behavioural

scenario retrieval was not a primary focus.

The methods reviewed address different aspects of

trajectory embedding and scenario retrieval, but tend

to either over-generalise or focus narrowly on specific

aspects of driving behaviour. Learning-based meth-

ods tend to oversimplify trajectory embeddings by re-

lying on MSE and overall scenario representations,

which may obscure critical geometric and relational

properties. Clustering methods focus primarily on

temporal alignment and pre-defined features, but fail

to capture the full complexity of multi-agent interac-

tions. Rule-based methods, while useful for detecting

specific manoeuvres, require significant manual effort

and may struggle to adapt to new or complex scenar-

ios. All presented methods lack searchability and in-

terpretability of the derived clusters, leaving out the

mapping of user queries or behavioural scenario de-

scriptions to the trajectory space.

3 METHOD

To overcome these limitations, a novel method is

proposed that aims to enhance the retrieval of driv-

ing scenarios by combining geometry-aware trajec-

tory embeddings with word embeddings from LLMs,

enabling behavioural-level searchability through nat-

ural language queries (Fig. 1). This approach is in-

tended to support V&V processes for ADS, ensuring

that behavioural patterns in unlabelled driving data

can be effectively analysed and retrieved through nat-

ural language or behavioural scenario descriptions.

3.1 Fine-Grained Trajectory

Embedding Using Geometric Loss

To generate a trajectory embedding that models the

fine-grained geometric aspects of behavioural scenar-

ios, a Variational Recurrent Autoencoder (VRAE) is

employed using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

cells with self-attention to capture sequential pat-

terns. The model is trained using the Hausdorff Dis-

tance (HD) as the loss function. Unlike the MSE,

which tends to generalise trajectory features, the HD

is able to preserve spatial properties by quantifying

the largest deviation between trajectory points. This

property is necessary to preserve the geometric at-

tributes required for fine-grained analysis of driving

behaviour, particularly in scenarios involving multi-

ple agents and dynamic interactions such as cut-ins,

overtaking manoeuvres or multiple lane changes.

The HD (d

H

) between two trajectories A =

{a

1

, a

2

, . . . , a

m

} and B = {b

1

, b

2

, . . . , b

n

} in a metric

space with the Manhattan (L1) distance d

M

(a, b) =

∑

d

i=1

|a

i

− b

i

| is defined as follows:

d

H

(A, B) = max

sup

a∈A

inf

b∈B

d

M

(a, b), sup

b∈B

inf

a∈A

d

M

(a, b)

This metric ensures that each point in A is close to

at least one point in B and vice versa, capturing tra-

jectory similarity based on maximum deviation. Us-

ing HD as a loss function within the VRAE allows for

a more accurate representation of trajectory structure,

which is required for behavioural scenario analysis.

VEHITS 2025 - 11th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

68

3.2 Clustering of Trajectory

Embeddings with HDBSCAN

Following embedding generation, trajectories are

clustered using Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial

Clustering of Applications with Noise (HDBSCAN)

(McInnes et al., 2017). It is well suited to dealing

with the distinctive features of unlabelled, naturalis-

tic trajectory data by identifying clusters of different

densities based on spatial and behavioural character-

istics from coarse to fine-grained properties. HDB-

SCAN helps to isolate clusters that reflect different

driving behaviours, allowing further analysis at a sce-

nario level. By explicitly accounting for noise in the

data, it also helps to identify unique patterns that rep-

resent outliers. This clustering step thus organises

the trajectory embeddings according to fine-grained

attributes, preserving the distinctions between the dif-

ferent driving behaviours observed.

3.3 Semantic Interpretation of

Scenarios Using LLMs

To make the generated embedding interpretable, each

trajectory cluster and individual scenarios within the

clusters are described using an LLM, in this approach

GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2024). This is achieved using a

prompt pipeline consisting of three main steps for

each sample in the dataset:

1. A single scenario is given as context with the task

to analyse overall properties such as traffic density

and each of the object trajectories in relation to

the infrastructure (road properties such as lanes)

as well as the interaction with other objects.

2. The corresponding cluster in the embedding space

is used to sample the five nearest neighbours of the

sample within its cluster to describe the intrinsic

attributes of the cluster by comparing the samples

to each other.

3. Each of the other clusters is considered by sam-

pling randomly five samples and describing them

as well as comparing them with the previously de-

scribed cluster.

Each description is referenced to the correspond-

ing data samples and associated clusters. This en-

sures interpretability at sample level, within clusters

and between clusters of behavioural scenarios, and

allows user queries to search from coarse to fine-

grained behavioural similarities and differences. This

step facilitates the translation of raw geometric data

into semantically meaningful interpretable represen-

tations, bridging the gap between abstract trajectory

data and functional driving behaviour. The integration

of LLMs improves searchability by linking trajectory

embeddings to a descriptive language.

3.4 Natural Language Scenario

Retrieval via GraphRAG Pipeline

The generated descriptions, combined with the corre-

sponding references in the dataset and the clustered

embedding, are indexed using a GraphRAG pipeline.

The idea of RAG is to provide a queryable external

context source for LLMs to answer targeted questions

about specific data not previously used to train the

LLM. GraphRAG implements this idea by modelling

the data into a knowledge graph, addressing relation-

ships between entities as well as general concepts by

clustering the knowledge graph (Edge et al., 2024).

By embedding the knowledge graph in the same em-

bedding as the LLM queries, natural language search

can be performed by referencing the previously gener-

ated descriptions as well as their associated data sam-

ples and trajectory embedding clusters.

4 EXPERIMENTS

4.1 Dataset

In this paper, a naturalistic vehicle trajectory dataset is

used to support trajectory embedding generation and

retrieval tasks.

The HighD dataset consists of more than 110,500

vehicles covering approximately 44,500 kilometres of

driving over 147 hours. The data, focusing on high-

way scenarios, was collected with a drone at six dif-

ferent German highway locations, overcoming com-

mon limitations of traditional traffic data collection

such as occlusion. The trajectory of each vehicle, in-

cluding manoeuvres and dimensions, was extracted

with a positioning error of less than ten centimetres

(Krajewski et al., 2018). For analysis, within the

frame of this research, the dataset is segmented into

15-second sequences to allow for the analysis of ve-

hicle interactions and manoeuvres at a higher granu-

larity.

4.2 Embedding Generation and Cluster

Analysis of Driving Scenarios

To analyse the embedding, both MSE and HD are

used as loss functions to generate the trajectory em-

bedding with VRAE. The differences identified are

compared by analysing the HDBSCAN clusters on

Large Language Model-Informed Geometric Trajectory Embedding for Driving Scenario Retrieval

69

a t-distributed Stochastic Neighbour Embedding (t-

SNE) projection and mapping general properties such

as number of lanes, lane change, speed, acceleration,

and traffic density to the embedding.

These metrics not only provide insight into the

specific behavioural characteristics of each cluster,

but also help validate the plausibility of behavioural

scenario representations, as clusters are expected to

reflect infrastructure characteristics, ego-object dy-

namics, as well as manoeuvres and interaction pat-

terns.

Both the description and the retrieval performance

of the proposed approach are validated using a set of

33 different user queries related to behavioural sce-

nario analysis (Table 1). Specifically, these queries

are categorised as follows:

• General Scene: Retrieval of scenarios based on

general properties such as traffic density or base

infrastructure such as amount of lanes.

• Infrastructure Manoeuvres: Focused retrieval

based on manoeuvre interactions with infrastruc-

ture elements such as lane markings (e.g. a lane

change).

• Ego Manoeuvres: Retrieval based on trajectory

characteristics and behaviour of the trajectory it-

self, which can be broken down into motion prim-

itives such as speed and acceleration.

• Object Interaction: Retrieval focused on inter-

actions between road users, capturing multi-agent

dynamics.

• Combinatorial Scenarios: Retrieval based on

combinations of general, infrastructure, ego ma-

noeuvres and interactions, such as simultaneous

high density traffic and lane change manoeuvres.

Scenario retrieval performance is assessed using

the Precision@k (prec@k) metric, measured across

different retrieval categories (General, Infrastructure,

Ego, Interaction and Combinatorics). Specifically, the

prec@k metric is used to determine the relevance of

the top five retrieved samples for each query. The av-

erage prec@k value for all queries belonging to the

same category is used for the analysis.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Analysis of Geometric Embedding

In order to evaluate the properties and feasibility of

geometric embedding using HD, a comparison with

an MSE-based embedding is performed.

(a)

(b)

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

(c)

2

3

4

(d)

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

(e)

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

(f)

Figure 2: Trajectory embeddings using MSE (a) and HD

(HD) (b), along with their corresponding embeddings of

scenario features such as the number of lanes (c, d) and lane

changes (e, f).

5.1.1 General Structure of the Embedding

Space and Resulting HDBSCAN Clusters

The MSE and HD embeddings, along with their re-

spective clustering results, show differences in cluster

granularity, as seen in the clustering results produced

by the HDBSCAN algorithm (Fig. 2a, 2b). The iden-

tified clusters show differences in coarseness between

the embedding methods, with a notable difference in

the number of clusters observed in each embedding

type, which is 8 for MSE and 49 for HD.

5.1.2 Mapping of Behavioural Scenario Features

to the Embedding Space

To illustrate the separability of features within clus-

ters, two features are mapped: one general (number

of lanes) and one trajectory-specific (lane change). In

both embeddings, clusters representing different lane

numbers are visually distinct (Fig. 2c, 2d). The map-

ping of lane changes shows different distributions,

with the MSE embedding showing a randomly dis-

tributed pattern of samples, whereas the HD embed-

ding shows these changes along the edges of visu-

ally separated clusters, as seen in the grey HDBSCAN

cluster (Fig. 2e, 2f).

VEHITS 2025 - 11th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

70

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

(a)

10

20

30

40

50

(b)

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

(c)

−10

−5

0

5

10

15

(d)

Figure 3: HD embeddings of driving scenario features, including mean velocity in [m/s] (a), number of road users (b), lateral

velocity change in [m/s²] (c) and longitudinal velocity change in [m/s²] (d).

Given these observations, while the MSE embed-

dings can be used to identify general attributes, the

ability to identify fine-grained details of the trajecto-

ries is significantly compromised. Consequently, only

the HD embedding is considered for the subsequent

analysis.

5.2 Driving Scenario Features

To analyse the interpretability and searchability of

the HD embedding, additional previously extracted

features such as mean velocity, number of objects,

lateral velocity change and acceleration are mapped

onto the embedding visualisation. These features are

also cross-referenced with the descriptions generated

by the LLM for the corresponding clusters.

The mean velocity evaluation shows a clear gradi-

ent across the clusters, with low speed scenarios con-

centrated on the left and high speed conditions on the

right (Fig. 3a).

The number of road users within a scenario fur-

ther supports this division, as a higher density of road

users appears on the left side of the visualisation (Fig.

3b). In particular, a dense cluster at the leftmost tip

of the embedding, characterised by a high number of

road users and low speed, suggests traffic congestion.

This observation is consistent with the LLM descrip-

tions, which highlight congestion and disrupted flow

in this area. Conversely, the right side of the visual-

isation, characterised by fewer road users, correlates

with high speed scenarios and continuous traffic flow.

Changes in lateral velocity are more pronounced

at the periphery of the clusters (Fig. 3c), consis-

tent with the HD embedding’s identification of lane

changes, particularly at the edges (Fig. 2f). The LLM

descriptions support this by noting lane changes and

multi-lane adjustments within the edges of the respec-

tive main clusters.

The longitudinal speed changes show the dynam-

ics of acceleration and deceleration across the sce-

narios (Fig. 3d). Acceleration values are concen-

trated on the left side of the embedding, where lower

General Scene

Infrastructure Manoeuvre

Ego Manoeuvre

Object Interaction

Combination

1 1 1 1

0.9

1

0.94

0.8

0.67 0.6

0.6

0.72 0.73

0.6

0.47

L1

L2

L3

Figure 4: Retrieval performance of the LLM for behavioural

queries and their combinatorics with three levels of detail

(average prec@5 over several queries).

speeds dominate, allowing greater acceleration poten-

tial. Conversely, deceleration values are concentrated

in the right-hand clusters, corresponding to the high-

speed conditions. This inversion, where lower speeds

allow greater acceleration and higher speeds involve

greater deceleration, is consistent with typical driving

behaviour, as confirmed by the LLM scenario descrip-

tions, which capture this contrasting pattern between

the low-speed, acceleration-rich areas and the high-

speed, deceleration-dominant clusters.

5.3 Retrieval Analysis

For retrieval analysis, the LLM is queried at three lev-

els of detail: L1, L2 and L3. Example queries are

listed in Table 1. The query results are shown in Fig-

ure 4, where darker tiles indicate better model per-

formance, with 0% being the lowest score and 100%

being the best possible score. As the prec@k is calcu-

lated based on the top five retrieved samples, values

up to 100% are possible for the average prec@k value

of several queries.

The performance of the model varies with the

complexity of the queries. At the lowest level of de-

tail (L1), simple queries, such as keeping the speed of

the ego trajectory constant, give an average prec@k of

98%. At the medium complexity level (L2), queries

such as ” pass-by from left” result in an average

Large Language Model-Informed Geometric Trajectory Embedding for Driving Scenario Retrieval

71

Table 1: Overview of query types for trajectory retrieval: Categorisation of General Scene, Infrastructure Manoeuvre, Ego

Manoeuvre, Object Interaction and Combination queries by level of complexity (L1, L2, L3). Text in italic denotes place-

holders for specific values (e.g., direction = left, speed value = 20 km/h)

Description Objective L1 Queries L2 Queries L3 Queries

General Scene

Retrieve trajectories of vehicles on a two-

lane highway; three-lane highway sce-

nario

Retrieve trajectories in moderate traffic

density; congested traffic conditions

Retrieve trajectories with high traffic den-

sity in lane number; heavy traffic in mid-

dle and left lanes with free traffic flow in

right lane

Infrastructure Manoeuvre

Retrieve trajectories of vehicles maintain-

ing lane number

Retrieve trajectories involving lane

changes at speeds above speed value;

performing aggressive lane changes

Retrieve trajectories showing lane change

to the direction; multi-lane changes of

different road users at the same time

Ego Manoeuvre

Retrieve trajectories of vehicles travelling

at a constant speed of speed value

Retrieve trajectories with acceleration;

deceleration; lateral movement without

lane change

Retrieve stop-and-go trajectories; acceler-

ation up to speed value; braking to below

speed value

Object Interaction

Retrieve trajectories following an object

at speed value; approaching an object at

speed value

Retrieve trajectories with pass-by ma-

noeuvre from the direction; cut-in at

speeds above speed value

Retrieve trajectories with evasive ma-

noeuvre; overtaking; merging into high-

way traffic in high density

Combination

Retrieve trajectories following a lane on a

two-lane highway with high acceleration

Retrieve trajectories showing lane change

after pass-by in moderate traffic

Retrieve trajectories with evasive ma-

noeuvre to the right to lane lane number

at high speeds; multi-lane changes of one

road user in heavy traffic

prec@k of 80.2%, indicating the ability to cover fine

granularities in the description of behavioural sce-

narios. At the highest level of complexity (L3),

queries such as ”evasive manoeuvre to the right at

high speed” are challenging and result in an average

prec@k of 62.4%.

Overall, the Infrastructure Manoeuvre category

achieves the highest performance across all levels,

with an average prec@k of 88.7%. Conversely, the

Combination category shows the lowest performance,

with an average prec@k of 65.7%.

An extract of the detailed output from the LLM in

response to a natural language query is shown in Table

2, which includes the exact query, the corresponding

retrieved trajectory, and a condensed response from

the LLM, shortened for total length.

Qualitative analysis of these responses reveals the

model’s deep overall understanding of the objects in-

volved and their relationships by querying the knowl-

edge graph. The LLM provides detailed references

within the knowledge graph, specifying information

such as concrete object IDs and precise speed and ac-

celeration values relevant to the queries. In partic-

ular, the model demonstrates high accuracy by pro-

viding the vehicle ID and specific time frames for

each queried manoeuvre. In addition, the LLM out-

put includes direct indices to data sources relevant to

the query context, supporting traceability across data

layers. Responses to complex queries remain clear

and comprehensive, providing descriptions that cap-

ture both the sample retrieved and its contextual pa-

rameters.

6 EVALUATION

The embedding analysis results indicate that the HD

embedding is highly effective for trajectory data.

Compared to the MSE embedding, the HD embed-

ding shows better performance in modelling and clus-

tering trajectories, allowing for fine-grained differen-

tiation of attributes such as lane change behaviour and

specific ego manoeuvres. In contrast, MSE embed-

ding primarily captures broader scenario characteris-

tics and lacks the resolution to distinguish between

detailed manoeuvres. Beyond the more distinct clus-

ters, the applicability of the HD embedding is re-

inforced by consistent performance across different

visualisations, such as the clear correlation between

high-speed scenarios and low object counts, and vice

versa. This geometric embedding approach facili-

tates the targeted search for behavioural scenarios and

supports nuanced trajectory analysis. The generated

LLM descriptions include the previously extracted

features in their descriptions at the same locations in

the same clusters as visualised in the embedding. This

further demonstrates the feasibility of the three-stage

cluster description by prompting an LLM for the pur-

poses of interpretability and searchability.

Evaluating the retrieval performance, with an av-

erage prec@k of 80.2%, the presented approach

shows that even higher levels of detail of the general

scene, infrastructure, ego manoeuvres as well as ob-

ject interactions can be described and retrieved. On

the other hand, the high degree of combinatorics in

the queries can be a challenge, with performance de-

grading towards higher levels of detail, affecting the

overall performance.

VEHITS 2025 - 11th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

72

Table 2: Detailed overview of trajectory retrieval queries: Examples of query types, corresponding top retrieved trajectories

and shortened responses from the LLM, highlighting different driving manoeuvres and traffic conditions in real-world highway

scenarios.

Query Top Retrieved Trajectory Shortened Answer of LLM

Retrieve trajectories in

dense traffic on the right

lane with low speed.

(General Scene, L3)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

xVelocity

In several highway scenarios, Lane 0, which is the rightmost lane, ex-

hibits dense traffic with vehicles maintaining low speeds. Vehicles

in Lane 0 generally show consistent following behavior, maintaining

steady speeds and positions without significant lane changes or aggres-

sive maneuvers. For instance, Vehicle ID 300 travels at below 9.3 m/s,

maintaining a consistent lane-following behavior without significant

speed variation [Data: Entities (981)]. Similarly, Vehicle 369 travels

slower at around 15.3 m/s, slightly decelerating over time and main-

taining its position in Lane 0, indicating moderate traffic density [Data:

Entities (963)]. Additionally, Vehicle 678 follows a steady path with

incremental velocities, further indicating a following behavior in Lane

0 [Data: Entities (193)]. These observations highlight the dense and

low-speed traffic conditions in Lane 0, contributing to the overall traffic

flow on the highway [Data: Reports (226); Entities (1480, 198, 347);

Relationships (697, 743, 741, 1839, 2039)].

Retrieve trajectories of a

lane change to the left.

(Infrastructure Maneuver, L2)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

xVelocity

Several vehicles in the dataset exhibit lane changes to the left, indicat-

ing maneuvers from a higher-numbered lane to a lower-numbered lane.

Notable examples include: Vehicle ID 273: Changes from Lane 1 to

Lane 2 at frame 2990, showing a leftward shift in trajectory [Data: Re-

ports (147); Entities (1956); Relationships (663, 1583, 3782)]. Vehicle

ID 2286: Moves from Lane 2 to Lane 1 at frame 27404, indicating a

smooth, controlled transition [Data: Reports (147); Entities (304, 309);

Relationships (2672, 128)]. Vehicle ID 2295: Lane change from Lane

1 to Lane 2 at frame 27488, demonstrating a smooth high-speed ma-

neuver [Data: Reports (147); Entities (307, 310); Relationships (2674,

129)]. Vehicle ID 1383: Leftward shift from Lane 1 to Lane 2 around

frame 16407[Data: Entities (630); Relationships (240)]. Vehicle ID

1176: Changes from Lane 1 to Lane 2 at frame 14070, possibly indicat-

ing an overtaking maneuver or adaptive lane positioning [Data: Entities

(90); Relationships (1099)].

Retrieve trajectories of a

multi lane change to the

left.

(Infrastructure Maneuver, L3)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

xVelocity

Vehicle 210 initiates in Lane 2 and shifts to Lane 0 around frame 2321,

with slight speed changes before and after the lane change, indicating

a maneuver to overtake or evade slower traffic [Data: Entities (4); Re-

lationships (15, 17, 663, 1583, 3782)]. Vehicle 2186 starts in lane 0

with a velocity around

˜

31.9 m/s initially and changes to lane 2 around

frame 2165, demonstrating a lane change maneuver without any signif-

icant speed variation [Data: Entities (1414); Relationships (478, 2763,

3955, 3962, 3969)]. Vehicle 273 changes lanes from Lane 2 to Lane 0

around frame 2990, indicated by a laneId change and a minor deviation

in y-velocity [Data: Entities (1956); Relationships (663, 1583, 3782)].

Vehicle 1994 starts in lane 0 and transitions to lane 1 with a higher xVe-

locity around 33.58 and noticeable x-Velocity, indicating a lane change

from 0 to 2, possibly for evasive maneuver [Data: Entities (1946); Re-

lationships (4371, 2107, 2109)].

Retrieve trajectories of a

aggressive lane change

over multiple lanes to the

right.

(Infrastructure Maneuver, L3)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

xVelocity

In the provided data, Vehicle 214 exhibits aggressive lane-changing be-

havior over multiple lanes to the right. Vehicle 214 maintains a high

speed ranging from 35.65 to 37.17 m/s and shifts between Lanes 0,

1, and 2 over various frames, indicating multiple lane changes. These

maneuvers suggest attempts to overtake other vehicles or adjust to vary-

ing traffic densities, reflecting a responsive and adaptive driving pattern

[Data: Reports (261); Entities (6); Relationships (21, 20, 22, 24, 19,

+more)].

Retrieve trajectories of an

evasive maneuver to the

right with a speed over

70 km/h.

(Combination, L3)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

xVelocity

The data provided indicates the presence of evasive maneuvers to the

right by vehicles with speeds over 20 m/s. Within the highway scene,

several vehicles exhibit high-speed driving with specific instances of

abrupt lane changes or swerving actions that qualify as evasive maneu-

vers. For instance: Vehicle 214, and Vehicle 221 are noted for high-

speed driving and dynamic lane-changing behaviors, which include

evasive actions intended to avoid potential collisions. These maneu-

vers go beyond strategic overtaking or adaptive driving, as they involve

rapid adjustments in trajectory to evade other vehicles. Additionally,

the entity labeled ”EVADE” confirms instances of evading within the

dataset, specifically highlighting scenarios where evasive actions were

observed. This entity references particular relationships and data points

(Entities 32 and 867; Relationships 1810) that document recorded eva-

sive maneuvers to the right by vehicles traveling over 20 m/s.

At the lowest levels of detail (L1 and L2), the

LLM retrieves scenarios with high accuracy, and the

descriptions it generates closely match the queried

behaviours. This high accuracy indicates that the

LLM effectively understands simple and moderately

detailed scenarios, capturing key trajectory features

and behavioural cues with little difficulty.

However, performance drops for the most com-

plex queries (L3). This drop is most noticeable

for queries that capture combined manoeuvres over

Large Language Model-Informed Geometric Trajectory Embedding for Driving Scenario Retrieval

73

longer periods of time, such as stop-and-go scenarios

or long overtaking manoeuvres. One reason for this

performance drop could be the segmentation of the

data into 15 second sequences. As a result, these sce-

narios cannot be adequately queried as they are not

properly embedded within this short time window. In

these cases, the LLM reports that there are few or no

such instances in the dataset, again demonstrating a

good understanding but limiting its retrieval perfor-

mance score for these queries. Choosing variable time

windows to capture both short and long term manoeu-

vre development could help to capture these manoeu-

vres with the presented method. Additional perfor-

mance challenges are particularly notable within the

Combination category, which captures combinatorial

queries of multiple behavioural elements. In many

cases, the response contains specific subsets of the

combinatorics, but often struggles to capture all re-

lated aspects for highly combinatorial queries at L2

and L3.

Qualitative analysis of the model responses shows

a comprehensive understanding of the LLM in terms

of the data samples and the associated clusters in the

geometric embedding space. By providing both data

and knowledge graph references, coupled with a full

text answer and detailed reasoning about the retrieved

scenarios, interpretability is facilitated.

7 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper presents a comprehensive approach for re-

trieving behavioural scenarios on unlabelled trajecto-

ries from real driving data. The geometric embed-

ding based on HD is able to capture detailed scenario

attributes such as infrastructure, specific features of

object trajectories as well as their interactions. The

guided description of the trajectory space by GPT-4o

combined with the indexing by a GraphRAG pipeline

allows users to query and analyse the generated repre-

sentation with natural language and behavioural sce-

nario descriptions without prior annotation and addi-

tional information extraction. The open context na-

ture of the LLM, by providing an open vocabulary,

allows queries that do not necessarily need to be con-

sidered prior to data extraction.

Future research could focus on improving the pro-

posed approach in several ways. First, the introduc-

tion of different segment lengths can be considered

to accommodate different granularities in manoeuvre

combinations, which would address potential perfor-

mance issues, such as the observed challenges in stop-

and-go scenarios as longer length takeovers. Subse-

quently, the use of alternative models to VRAE, such

as Transformers, may also prove beneficial for ex-

tended context representation. This can be coupled

with the inclusion of additional scenario parameters

based on the 6LM for enhanced context representa-

tion and search. The database should be extended

beyond the highway scenarios in the highD dataset,

such as intersections, urban scenarios and other real-

world use cases. To evaluate the scenario retrieval

performance, ground truth datasets should be created

that allow for additional performance metrics such as

Recall@k. This can be combined with the evalua-

tion of different alternative prompting and RAG ap-

proaches to improve retrieval specifically for combi-

natorial queries. Besides the HD which introduces a

spatial distance, additional metrics should be evalu-

ated with respect to the resulting embedding space for

driving scenarios, specifically including temporal and

spatial distances. Finally, the method should be eval-

uated and improved on the basis of user studies with

the involvement of V&V engineers, investigating the

most important types of queries as well as drawing the

relation to the application related to the SOTIF stan-

dard.

REFERENCES

Edge, D., Trinh, H., Cheng, N., Bradley, J., Chao, A., Mody,

A., Truitt, S., and Larson, J. (2024). From local to

global: A graph rag approach to query-focused sum-

marization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.16130.

Elspas, P., Klose, Y., Isele, S. T., Bach, J., and Sax, E.

(2021). Time series segmentation for driving scenario

detection with fully convolutional networks. In VE-

HITS, pages 56–64.

Elspas, P., Langner, J., Aydinbas, M., Bach, J., and Sax,

E. (2020). Leveraging regular expressions for flexible

scenario detection in recorded driving data. In 2020

IEEE International Symposium on Systems Engineer-

ing (ISSE), pages 1–8. IEEE.

Hoseini, F., Rahrovani, S., and Chehreghani, M. H. (2021).

Vehicle motion trajectories clustering via embedding

transitive relations. In 2021 IEEE International In-

telligent Transportation Systems Conference (ITSC),

pages 1314–1321.

International Organization for Standardization (2022).

Road vehicles - safety of the inteded fuctionality. ISO

21448:2022(E). ICS: 43.040.10.

Krajewski, R., Bock, J., Kloeker, L., and Eckstein, L.

(2018). The highd dataset: A drone dataset of natural-

istic vehicle trajectories on german highways for val-

idation of highly automated driving systems. In 2018

21st International Conference on Intelligent Trans-

portation Systems (ITSC), pages 2118–2125.

McInnes, L., Healy, J., and Astels, S. (2017). hdbscan: Hi-

VEHITS 2025 - 11th International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems

74

erarchical density based clustering. Journal of open

source software, 2(11):205.

Montanari, F., German, R., and Djanatliev, A. (2020). Pat-

tern recognition for driving scenario detection in real

driving data. In 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Sym-

posium (IV), pages 590–597. IEEE.

OpenAI, I. (2024). Hello gpt-4o. https://openai.com/index/

hello-gpt-4o/. Accessed: 2024-08-29.

Ries, L., Rigoll, P., Braun, T., Schulik, T., Daube, J., and

Sax, E. (2021). Trajectory-based clustering of real-

world urban driving sequences with multiple traffic

objects. In 2021 IEEE International Intelligent Trans-

portation Systems Conference (ITSC), pages 1251–

1258.

Scholtes, M., Westhofen, L., Turner, L. R., Lotto, K.,

Schuldes, M., Weber, H., Wagener, N., Neurohr, C.,

Bollmann, M. H., K

¨

ortke, F., et al. (2021). 6-layer

model for a structured description and categoriza-

tion of urban traffic and environment. IEEE Access,

9:59131–59147.

Sohn, T. S., Dillitzer, M., Ewecker, L., Br

¨

uhl, T., Schwa-

ger, R., Dalke, L., Elspas, P., Oechsle, F., and Sax, E.

(2024). Towards scenario retrieval of real driving data

with large vision-language models. In 10th Interna-

tional Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelli-

gent Transport Systems (VEHITS 2024), pages 496–

505.

Sonntag., M., Vater., L., Vuskov., R., and Eckstein., L.

(2024). Detecting edge cases from trajectory datasets

using deep learning based outlier detection. In Pro-

ceedings of the 10th International Conference on Ve-

hicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems -

VEHITS, pages 31–39. INSTICC, SciTePress.

Watanabe, H., Tobisch, L., Rost, J., Wallner, J., and Prokop,

G. (2019). Scenario mining for development of

predictive safety functions. In 2019 IEEE Interna-

tional Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety

(ICVES), pages 1–7. IEEE.

Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., Bosma, M., ichter,

b., Xia, F., Chi, E., Le, Q. V., and Zhou, D. (2022).

Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large

language models. In Koyejo, S., Mohamed, S., Agar-

wal, A., Belgrave, D., Cho, K., and Oh, A., editors,

Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems,

volume 35, pages 24824–24837. Curran Associates,

Inc.

Large Language Model-Informed Geometric Trajectory Embedding for Driving Scenario Retrieval

75