Yearning for Love: Exploring the Interplay of Parasocial Romantic

Attachment, Loneliness, and Purchase Behavior Within Dating

Simulation Games

Jeanette Buhleier

a

, Benjamin Engelst

¨

atter

b

and Omid Tafreschi

c

Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences, Darmstadt, Germany

Keywords:

Dating Simulation Games, Romantic Parasocial Relationships, Romantic Loneliness, Free-to-Play, Purchase

Behavior.

Abstract:

Female-oriented dating simulation games (i.e., games centered around the romantic relationships between a

female player and its game characters) have grown increasingly popular internationally and developed into

a profitable business model. The genuine feelings of love players develop for these virtual characters (i.e.,

parasocial love), particularly the motifs behind such attachments, have garnered rapid curiosity. Applying the

parasocial compensation hypothesis, this study conducted an online survey among female players of the free-

to-play dating simulation game Mystic Messenger to explore romantic loneliness as a motivator for players’

parasocial love and its impact on players’ purchasing behavior. The correlation analysis revealed a weak

negative relationship between romantic loneliness and parasocial love, indicating a complementary rather than

compensatory function of such attachments. Further, while the strength of para-romantic feelings did not drive

in-game spending, romantic loneliness was negatively associated with willingness to invest money. These

findings suggest that other motivations drive real-money investments in romance-themed games, highlighting

the complexity of player behavior in this context.

1 INTRODUCTION

More than 39000 $ – that was the worth of a recent

LED advertisement a Chinese women splurged on her

‘boyfriend’, one of the love interests in the popular

mobile game Mr Love: Queen’s Choice (PaperGames

2017). Clearly, the world of love has gone digital in

a spectacular way (Huang, 2018); not just in Japan,

where these so-called dating simulation games (short:

dating sims) first originated from (Schwartz, 2018).

In fact, dating sims have become an international phe-

nomenon, prompting players to spend increasingly

more time and money on nurturing these so-called

parasocial romances – one-sided romantic feelings

people develop for media characters (Tukachinsky,

2010). Indeed, it seems like players have come to

deeply care about these fictional relationships, openly

swooning over their virtual love interests as if the in-

timacy provided by them was real (Schwartz, 2018).

Amongst rising tendencies of women specifically to

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-3278-8452

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6865-9918

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2284-4349

stay single and independent, the growing popularity

of dating sims have raised concerns on their potential

function as a replacement for real-life intimacy and

affection.

Whether individuals turn to media figures to com-

pensate for a deficit in their social lives has long been

controversially discussed. While studies revealed that

these so-called parasocial bonds cannot compensate

for unmet social needs, e.g., (Canary and Spitzberg,

1993; Chory-Assad and Yanen, 2005; Rubin et al.,

1985), most of the existing research focused on tradi-

tional mass media personalities, e.g., (Hu et al., 2021;

Wang et al., 2008), or failed to align specific paraso-

cial experiences with distinct unmet needs, e.g., (Ru-

bin et al., 1985; Wang et al., 2008). Dating simula-

tion games have largely been overlooked in these con-

templations despite their unique appeal. As players

become active participants in the simulated romance,

these games may afford gratifications that traditional

mass media characters cannot provide. This paper

aims to close this research gap by looking at compen-

satory effects of parasocial experiences from the per-

spective of interactive video games. To do so, we con-

Buhleier, J., Engelstätter, B. and Tafreschi, O.

Yearning for Love: Exploring the Interplay of Parasocial Romantic Attachment, Loneliness, and Purchase Behavior Within Dating Simulation Games.

DOI: 10.5220/0013203800003929

In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2025) - Volume 2, pages 405-416

ISBN: 978-989-758-749-8; ISSN: 2184-4992

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

405

ducted a quantitative survey addressing the following

research questions:

RQ1: Which role does the longing for romantic in-

timacy play in developing romantic feelings for dating

sim characters?

RQ2: How do romantic loneliness and romantic

feelings for the dating sim characters relate to play-

ers’ in-game purchasing behavior?

RQ1 aspires to explore what draws individuals to

engage in romantic parasocial relationships with vir-

tual characters in dating simulation games, more pre-

cisely those targeted at a female audience. By do-

ing so, it adopts the angle of parasocial compensation

theory by focusing specifically on feelings of roman-

tic loneliness, that is, an inherent desire for love and

intimacy, and their influence on feelings of paraso-

cial love. Moreover, considering the immense com-

mercial success of some titles within the niche, RQ2

strives to unveil how either of these feelings may af-

fect players’ willingness to invest real money in these

games.

Against the backdrop of the research questions,

we first discuss the mechanisms of dating simulation

games as well as the phenomenon of romantic paraso-

cial relationships and its related concepts. Next, we

explain the utilized methodology before detailing the

results of the analysis. After discussing key findings,

this paper concludes with a summary and research

outlook.

2 RESEARCH BACKGROUND

AND HYPOTHESES

The rise of interactive video games has altered how

individuals can get involved with fictional media char-

acters – especially romantically. Among these games,

dating sims have enabled players to cultivate rich and

meaningful virtual romances with these game char-

acters. Once these feelings spill over into real-life,

researchers (Tukachinsky, 2010; Waern, 2010) refer

to them as parasocial love which may closely resem-

ble experiences of traditional romantic relationships

– in their development, dissolution, or gratifications.

Hereafter, the concept of female-oriented dating sims,

the notion of romantic parasocial relationships as well

as their possible role in romantic need fulfillment will

be looked at more closely, before deriving our re-

search hypotheses based on the existing literature.

2.1 Female-Oriented Dating Simulation

Games

Female-oriented dating simulation games are

romance-themed single player games that blend

elements of simulation games with characteristics of

visual novels (Saito, 2021). They typically revolve

around a playable female main character (MC) and

a selection of attractive – and mostly male – ro-

manceable non-playable characters (NPCs), so-called

love interests. The purpose of these games is for the

player to win over the affections of one or more of

these love interests by interacting with them through

pre-scripted dialogue. These interactions often hold

heavy romantic connotations and are interspersed

with accompanying romantic scenes that slowly build

up the virtual relationship. Through their chosen

responses, players can shape the love story and

experience multiple idealized relationship scenarios

with their virtual lovers (Schwartz, 2018; Taylor,

2007).

Although originally limited to the Japanese mar-

ket, the advances of the Internet and emergence of

new distribution channels have significantly driven

the international success of dating sims. In 2020,

the niche counted roughly 22 million active players

worldwide, ramping up significant revenues while do-

ing so (Russon, 2020). Leading Japanese developer

Voltage, for instance, recently reported annual earn-

ings of roughly 33 million $

1

across its more than

100 dating sim titles (Voltage Inc., 023a; Voltage Inc.,

023b). Notably, most modern dating sims employ a

free-to-play or freemium model which enables play-

ers to make in-game purchases (i.e., micropayments)

at different points in the game. These in-app pur-

chases typically involve ways to progress faster in the

game, for example, by granting the players access to a

certain number of chapters a day, speeding up game-

play or boosting certain stats that will help to suc-

cessfully pursue the chosen romantic route (Ganzon,

2022). At the same time, players can enrich the vir-

tual relationship by unlocking additional content such

as new interactions like phone calls, messages, or ro-

mantic dates. Some games even offer epilogues or

additional side stories which allow players to extend

the relationship beyond the initial playthrough of the

main story. As most of these purchases are character-

focused, they require the player to have formed some

sort of attachment to these characters (Ganzon, 2022).

In some ways, then, players’ love for their virtual

boyfriend has become a commodity in these games

1

Earnings of 5392 million Yen taken from official Volt-

age financial highlights and converted to $ (exchange rate

on January 17: 1 Yen = 0,0068 $) for easier comparability.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

406

as females invest increasingly more money into nur-

turing the relationships with these fictional characters.

2.2 Romantic Parasocial Relationships

How people form emotional connections to media

characters has been a central theme in media and

communication research for many years. These at-

tachments were coined parasocial relationships (PSR)

(Horton and Wohl, 1956). PSR are genuine feelings

people develop for media characters throughout a se-

ries of individual encounters (Liebers and Schramm,

2019). They typically manifest in a sense of inti-

mately knowing, understanding, and caring for the

character, as well as thinking or talking about them

outside of reception. Because these bonds are asym-

metric and lack reciprocity, they typically remain

bound to the fantasy of the audience (D

¨

oring, 2013).

Although parasocial relationships have often been

compared to friendships, Tukachinsky called for a

more nuanced treatment of such attachments, intro-

ducing romantic parasocial relationships (PSRR) to

conceptualize the feeling of being in love or being

infatuated with certain media characters (Tukachin-

sky, 2010). Compared to amicable parasocial bonds

which relate to feelings of trust or being fond of the

character, romantic parasocial relationships are mo-

tivated by strong romantic affection as well as sex-

ual and emotional attraction towards the media figure

(Tukachinsky, 2010). The more intense these feelings

are, the more effort and time are spent on these rela-

tionships, often involving a significant amount of ide-

alization and fantasizing about being with the roman-

tic parasocial partner (Erickson et al., 2018). These

parasocial partners can be real-life celebrities or ac-

tors but can extend towards virtual game characters

as well (Tukachinsky, 2010). Indeed, scholars ana-

lyzing online fan discussions have found that play-

ers of role-playing video games regularly mentioned

genuine feelings of love and affection for their non-

playable counterparts regardless of them being only

visual representations of real people (Coulson et al.,

2012; Mallon and Lynch, 2014). Some players even

noted that these feelings had prompted them to ex-

tend additional effort into their gameplay (Burgess

and Jones, 2020).

At first glance, PSRR with media characters may

appear to have little in common with romantic at-

tachments in real life. After all, genuine reciprocated

love and affection as well as physical dimensions of

romance remain entirely out of reach – especially

where fictional characters are concerned (Karhulahti

and V

¨

alisalo, 2020). Yet, romantic parasocial rela-

tionships have shown several astounding parallels to

interpersonal relations in how they are developed and

maintained (Tukachinsky and Stever, 2019). Like

with social relations, initial attraction to the me-

dia character is of particular importance, especially

when it comes to romantic interests (Sphancer, 2014;

Tukachinsky, 2010). Frequent exposure, as well, has

been found to be essential for parasocial bonds to

form (Gleich, 1997). As people grow to learn more

about the character, these experiences add up and

create a shared history (Branch et al., 2013; Hart-

mann, 2016a). Similar values, experiences and back-

grounds further contribute to strong emotional re-

sponses towards these characters (McPherson et al.,

2001; Turner, 1993), making these relationships feel

“very human, very warm, and very caring” (Mey-

rowitz, 1994). Not surprisingly, the dissolution of

these bonds can elicit strong negative responses akin

to distress upon break-up experiences in real life (Eyal

and Cohen, 2006).

2

Unlike real-life relationships, however, romantic

parasocial relationships bear hardly any risks and har-

bor little to no obligations (Schiappa et al., 2011). As

individuals have full control over the relationship and

can engage with different types of characters, these

bonds may be an easy and appealing way for wish ful-

fillment without the pitfalls of real-life romances like

fear of rejection or infidelity (Caughey, 1986). Dat-

ing sims, specifically, offer a canvas where romantic

relationships can be quickly cultivated with minimal

effort. The players have full agency over their virtual

romances and can curate relationships on their own

terms.

2.3 Parasocial Compensation

Hypothesis & Impact on Purchasing

Behavior

People possess an inherent desire for love and inti-

macy, a longing ultimately fulfilled by a committed

romantic partnership. Yet, if this love appears fickle

or temporarily unavailable, people may find other

means to stave off unmet romantic needs (Baumeister

and Leary, 1995). Considering the close resemblance

to interpersonal relationships and the emotional re-

sponses to media characters, one such alternative may

be afforded by engaging in romantic parasocial re-

lationships with dating sim characters (Gardner and

Knowles, 2008). Indeed, the parasocial compensa-

tion hypothesis assumes that lonelier people are more

2

Dissolution of parasocial bonds, typically referred to

as parasocial break-up, may occur when a character dies,

the media is discontinued or completed. In such cases, the

bond is no longer being reinforced and be cut abruptly or

fizzle out (Eyal and Cohen, 2006).

Yearning for Love: Exploring the Interplay of Parasocial Romantic Attachment, Loneliness, and Purchase Behavior Within Dating

Simulation Games

407

likely to develop stronger bonds with media figures

to compensate for unmet social needs (Hartmann,

2016b). In the context of romantic parasocial phe-

nomena, this loneliness may be understood as roman-

tic loneliness – a yearning for romantic intimacy that

is caused by deficits in people’s love lives, for exam-

ple, due to an unsatisfying partnership or the overall

lack of a romantic partner (Hu et al., 2021).

While numerous studies have aimed – and failed

– to find evidence for the parasocial compensation

hypothesis in the broader sense of parasocial phe-

nomena and loneliness, e.g., (Canary and Spitzberg,

1993; Chory-Assad and Yanen, 2005; Rubin et al.,

1985), only few scholars have considered this no-

tion from the perspective of romance and its related

needs. (Wang et al., 2008), for instance, compared

distinct loneliness dimensions and how they inter-

acted with parasocial experiences with mass media

personae. Yet, despite this more nuanced undertak-

ing, they found no evidence for compensatory effects

with respect of romantic loneliness. (Hu et al., 2021)

later expanded on this approach and investigated ro-

mantic loneliness in the specific context of roman-

tic parasocial phenomena. Across a sample of Chi-

nese students, they anticipated that romantic feelings

for the chosen parasocial partner would be more pro-

nounced for romantically lonely participants. Against

these expectations, however, the alignment of these

dimensions did not confirm romantic deficits to be a

motivator for parasocial love. On the contrary, it was

found, that less romantically lonely respondents de-

veloped stronger attachments and more often fanta-

sized about them. These implications may point to

complementary rather than compensatory functions

of parasocial relationships regardless of their nature

(Wang et al., 2008). Notably, however, both stud-

ies either applied a more generalized understanding

of parasocial relationships (Wang et al., 2008) or fo-

cused exclusively on traditional media characters (Hu

et al., 2021). In contrast to traditional mass media,

romantic relationships in dating sims are actively ex-

perienced with characters designed to cater to roman-

tic fantasies without any risks involved. In this vein,

players experiencing deficits in their love lives may

be more susceptible to the affection of these charac-

ters to compensate for unpleasant or insufficient ro-

mantic encounters in the real world. Therefore, it is

hypothesized:

H1: Players high in romantic loneliness exhibit

stronger parasocial love for dating sim love interests.

Compared to dating or married individuals, people

without a romantic partner are more sensitive to suf-

fering romantic loneliness (Adamczyk, 2016; Bernar-

don et al., 2011). In view of this, single players may

be more inclined to compensate for unmet roman-

tic needs by seeking romantic relationships in dating

simulation games. (Adam and Sizemore, 2013), as

an example, found that romantic parasocial relation-

ships with mass media personae provided benefits not

unlike those gained in real-life partnerships. These

benefits included feeling overall happier, feeling bet-

ter about themselves or less lonely and increased the

more an individual was invested in the romance with

the media persona. Interestingly, singles reported to

draw stronger benefits from their parasocial partner

than their dating counterparts. Likewise, (Liebers,

2022) observed that romantic parasocial relationships

were stronger for non-dating individuals and those re-

porting less satisfaction in their current partnership.

This suggests that in the absence of a (satisfying) ro-

mantic partner, individuals may look towards media

characters to derive certain romantic gratifications.

Consequently, it seems reasonable to argue that play-

ers currently not in a romantic relationship more heav-

ily rely on romantic attachments to their virtual love

interests to alleviate feelings of romantic loneliness

than dating players. Thus, it is assumed that:

H2: There is a difference in the relationship be-

tween romantic loneliness and parasocial love for

dating and non-dating players.

When players develop strong romantic feelings

for characters in games they play, they experience a

heightened sense of emotional investment. This emo-

tional investment can lead to a desire to enhance their

gameplay experience and nurture the bond with their

virtual lover (Mallon and Lynch, 2014). Many mod-

ern dating sims are specifically designed to offer in-

game purchases tied to elevating the romantic experi-

ences in the game. For example, by positively influ-

encing the relationships or offering additional content

to cater to the provided fantasy (Ganzon, 2022). In

pursuit of this fantasy, players may not stop at simply

immersing themselves into these stories but actively

attempt to enhance these experiences by displaying

specific purchasing behavior (Hirschman, 1983). In

other words, the more players have grown to love and

care for their virtual lover – and, by extend, the fan-

tasy they provide – the more they might be willing to

invest money to enrich it. Consequently, it is derived

that:

H3: Players high in parasocial love are more

likely to invest money in dating simulation games.

Unlike traditional media characters such as actors

or idols who individuals can encounter in other me-

dia formats or even in real life, the fictional nature of

dating sim characters essentially binds them to their

specific media contexts. Once the game has ended

and the romantic parasocial relationship is no longer

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

408

enforced through regular interactions, the bonds play-

ers curated with their virtual partners eventually fizzle

out (Branch et al., 2013). The loss of this relationship

may result in distress not unlike real-life break-up ex-

periences (Eyal and Cohen, 2006). Lonelier individ-

uals have been prone to suffer from this dissolution,

suggesting a more intense emotional dependence on

parasocial relationships as a need satisfier (Eyal and

Cohen, 2006). Modern dating simulation games in-

creasingly offer in-game purchases to expand these

virtual relationships through additional game content.

In view of this, romantically lonely players may have

a stronger urge to invest real money in-game to pre-

serve the fantasy of the romantic relationship and con-

tinue receiving love and affection from their paraso-

cial partner. This leads to our final hypothesis:

H4: Players high in romantic loneliness are more

likely to invest money in dating simulation games.

Following the above-outlined theoretical consid-

erations, we collected data to thoroughly examine the

hypotheses and further the research objective of this

paper. To do so, we adopted a cross-sectional study

design which we will explain in the following.

3 METHODOLOGY

An online survey was chosen as a suitable approach

for investigating the above derived research hypoth-

esis. In doing so, this study focuses particularly on

the female-oriented dating simulation game Mystic

Messenger (MysMe). The measures leveraged for this

study included a combination of established research

scales as well as questions specifically created for the

study. Ahead of distribution, the survey was tested

through a series of face-to-face interviews which were

conducted in May 2022. Where applicable, amend-

ments were incorporated into the final questionnaire.

3.1 Mystic Messenger

Launched in 2016, MysMe is a free-to-play dating

simulation game that revolves around a female main

character and seven romanceable love interests who

are part of a mysterious charity organization called

RFA. Roped into joining their charity as the new party

planner, the player soon discovers that each RFA

member has their tribulations and secrets to navigate

through.

As a mixture of the slice-of-life and thriller genre,

MysMe expertly exploits players’ dependency on

their phones, leveraging the interface and functions

of well-known messenger apps to create a new and

immersive dating sim experience that unfolds in real-

time across eleven weekdays (Ganzon, 2019). Unlike

other games within the genre, MysMe almost entirely

takes place in the game’s in-game chatroom which

opens every two to three hours and is used to inter-

act and romance one of the available love interests.

Missed interactions and additional story content can

be bought using the in-game currency hourglasses.

Due to this unique gameplay approach and the

genuine character interactions, the game has received

broad international acclaim since its release and has

become one of the most successful titles within its

niche. Downloadable for both Android and iOS, the

game currently counts more than five million down-

loads in Google Play Store, ranging at a high 4.6 stars

with more than 440000 reviews (Google Play, 2023).

Albeit numbers on revenue remain unclear, the fact

that its developer Cheritz donated more than 100000

$ to charity organizations within a few months of its

release speaks for MysMe’s overall commercial suc-

cess (Cowley, 2018). Given the above-mentioned ex-

planations, MysMe is considered an appealing avenue

to examine the interplay of unmet romantic needs,

parasocial love and purchasing behavior.

3.2 Measures

To investigate the research hypothesis and answer

the research question, we first defined several mea-

sures, covering the gameplay of the chosen game con-

text, pre-defined measurement scales for parasocial

love and romantic loneliness as well as several demo-

graphic parameters.

MysMe Gameplay Habits. To capture MysMe

specific gameplay behavior, five questions related to

how players engaged with the game in the past. These

questions asked about whether the game had been

played previously, how long it had been played, if

players engaged with it in the past six months, if

they had repeated a romance more than once, and

whether they had ever used the game’s in-game cur-

rency hourglasses. Players’ investment of real-game

money was measured by asking if they had previously

spent money on the game and, if so, how much money

they had spent and their reasons for spending money.

Parasocial Love. Two established scales were

used to measure the intensity of players’ romantic

feelings for their love interests. Firstly, participants

were asked to rank eleven items of the parasocial

love subscale of Multiple-Parasocial Relationships-

Scale (MPSR) proposed by (Tukachinsky, 2010).

Items reflected both physical attraction towards and

emotional closeness with the chosen media charac-

ter, including, for example, ‘I find MysMe charac-

ter very attractive physically’ or ‘MysMe character

Yearning for Love: Exploring the Interplay of Parasocial Romantic Attachment, Loneliness, and Purchase Behavior Within Dating

Simulation Games

409

would be the perfect romantic partner for me’. Sec-

ondly, the recently introduced Adolescent Romantic

Parasocial Attachment Scale (ARPA) (Erickson and

Dal Cin, 2018) was employed, expanding PSL sub-

scale (Tukachinsky, 2010) by incorporating cognitive

aspects (two items, e.g., ”I want to know as much as

I can about MysMe character.”), more in-depth affec-

tive experiences (three items, e.g., ”My relationship

with MysMe character makes me feel happy.”) as well

as the element of romantic fantasy (three items, e.g.,

”I often daydream about MysMe character.”). Re-

spectively, one item of the cognitive and two items

of the fantasy dimension were omitted as they did

not fit the fictional nature of the MysMe characters

(e.g., ”I imagine that MysMe character will some-

day pick me out of a crowd and see me as special.”).

Both scales were ranked from 1 (”strongly disagree”)

to 7 (”strongly agree”) with higher scores indicat-

ing higher intensity of PSL. To capture the full scope

of romantic parasocial experiences, both MPSR-PSL

and ARPA scale were combined

3

, with the combined

scale achieving excellent reliability (α = .94).

Romantic Loneliness. To investigate whether

players romantic loneliness motivated stronger feel-

ings of parasocial love, respondents were asked to

complete eleven items of the Romantic Loneliness

subscale (DiTommaso and Spinner, 1993). The sub-

scale was originally created as part of the Social and

Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA). Ex-

amples of the romantic loneliness items included ”I

find myself wishing for someone with whom to share

my life” and ”I have someone who fulfills my emo-

tional needs (reverse coded)” among others. Rankings

for each item spanned from 1 (”strongly disagree”)

to 7 (”strongly agree”) with higher scores hinting at

stronger feelings of romantic loneliness. Consistent

with previous studies (Hu et al., 2021; Wang et al.,

2008), the subscale yielded reliability at a very good

level (α = .85; M = 3.95; SD = 1.33).

Player Demographics. Lastly, participants were

asked a series of personal questions, covering stan-

dard information like their age, ethnical identity, cur-

rent occupation and average yearly income. As it

could not be ruled out that MysMe attracted non-

3

A Spearman correlation was performed between the

individual subscales to eliminate potential redundancies.

Correlation confirmed positive relationships between all

subscales (p < .001 for all), however the strong correlation

between the ARPA fantasy and PSL Emotional subscale

(r = 0.807; p < .001) pointed to the possibility of essentially

measuring the same constructs (Field, 2024). Accordingly,

the three items included in the ARPA fantasy scale were

dropped after an additional review of scale contents, seeing

as they closely resembled items within the PSL Emotional

subscale.

female players as well, a question about gender iden-

tity was added. To allow conclusions about players’

romantic loneliness, participants were requested to

disclose whether or not they were currently in a ro-

mantic relationship with anyone.

3.3 Sample & Procedure

Participants were recruited from MysMe specific on-

line communities on Reddit, Amino App and Face-

book via sharing of the survey link. Permission was

granted by the moderators of the respective forum

prior to posting the invitation. Alongside emphasizing

the anonymity of the survey, volunteers were given

the option to win a play store gift card to increase

the participation rate. Over a two-week survey pe-

riod in August 2022, a total of 855 participants com-

pleted the survey. However, several participants were

omitted from the sample due their lack of fit to the

research criteria. This included respondents who had

never played MysMe, admitted to not having played

the game the past 6 months, players under 18 and

players who did not identify as female, leaving a fi-

nal sample of N = 402 female players.

Most players were between 18 and 30 years (85%)

with a few players aged 41 and above (1.2%). With

regards to ethnicity, most players identified as Cau-

casian (66.4%), Asian (14.9%) or Hispanic (10.2%).

Most respondents had a full-time job (39%), stud-

ied (35.1%) or were currently looking for employ-

ment (17.2%). A majority earned between 35 000 and

75 000 $ (41.5%) annually or ranged below 15000 $

(28.4%). More than half of the players declared to be

currently married or in a committed romantic relation-

ship (62.4%). In terms of gameplay behavior, play-

ers indicated to have played MysMe for a little more

than two years on average (M = 2.002;SD = 1.5803).

Most of the players had engaged with any of MysMe’s

characters between one and six times (81.6%). De-

spite MysMe being a F2P title, 70% of the partici-

pants revealed to have spent money on the game. To-

tal investments ranged between 5 and 99.99 $ (48%)

for most, while 12% of respondents expended more

than 100 $ on the game. Reasons for investing money

mainly included unlocking new routes (62%) or ac-

cess to additional content (62.8%).

4 RESULTS

Hypothesis 1 suggested that players high in roman-

tic loneliness would also exhibit stronger romantic

feelings for their dating sim love interest. To exam-

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

410

ine this relationship, a Pearson correlation

4

was con-

ducted after calculating the mean scores for both ro-

mantic loneliness and parasocial love. Against expec-

tations, a non-significant relationship between both

variables emerged (r = −.048, p = .336) suggest-

ing that players’ romantic loneliness does not play

a role in developing romantic feelings for their vir-

tual love interests. As a result, hypothesis 1 is re-

jected. This effect, however, might have been driven

by the rather large share of dating participants within

the sample as studies (Adam and Sizemore, 2013;

Liebers, 2022) have shown that dating status, indi-

vidually, has effects on both the extent of roman-

tic loneliness and romantic feelings for media char-

acters. Therefore, it was asserted that non-dating

players would experience stronger romantic attach-

ments to their love interests to satisfy latent unful-

filled romantic needs (H2). Two independent sam-

ple t-tests

5

were run to first examine if potential dif-

ferences existed between dating and non-dating play-

ers. As anticipated, the comparison of romantic lone-

liness revealed a significantly stronger yearning for

love among non-dating (M = 5.23; SD = 0.94) than

dating players (M = 3.18;SD = .84), with differ-

ences between both groups appraised as very high

(t(287.82) = 21.92, p < .001, d = 2.32). Feelings of

parasocial love for a love interest, in comparison,

were not significantly different between non-dating

(M = 5.21; SD = 1.10) and dating participants (M =

5.23;SD = 1.16;t(400) = −.252, p = .80, d = −.03).

Albeit surprising, this points at the possibility that

romantic loneliness, regardless of relationship status,

does not play a role when it comes to romantic feel-

ings for dating sim characters. To account for poten-

tial moderation effects of dating status, a moderation

analysis was performed using the PROCESS macro

by (Hayes, 2022) with parasocial love as the outcome

variable, romantic loneliness as predictor and dating

status as the moderating variable. Both predictor and

moderator were mean centered. The analysis applied

bootstrapping with 5000 samples and heteroscedas-

ticity consistent standard errors (HC3; (Davidson,

4

Pearson correlation was chosen as neither linearity nor

normalcy of distribution could not be assumed after ex-

amining the variables via scatterplot and the Shapiro-Wilk

test (p < 0.001) for both romantic loneliness and parasocial

love.

5

Studies have found the t-test to be rather sturdy in

terms of non-normal distribution in cases where samples

sizes were higher than n = 30 (Bortz and Schuster, 2010).

Considering the sample sizes of both contrasted groups

(dating : n = 251; non − dating : n = 151), this requirement

was neglected. Outliers, too, were checked in advance us-

ing a box plot. Ultimately, however, they were kept within

the sample as they were considered rather weak.

1993) to determine confidence intervals. The overall

model was weakly significant (F(3, 398) = 2.25, p =

.082, R

2

= .0151). However, the moderation analysis

did not provide significant evidence that dating status

moderated the effect between romantic loneliness and

parasocial love (∆R

2

= .0006, F(1, 398) = 0.27, p =

.60, 95%CI[−.3188, .1724]). To conclude, hypothesis

2 has to be rejected.

Alongside romantic loneliness as a motivator for

parasocial love with virtual characters, another focus

of this study is on how either feeling affected the will-

ingness to invest real money within a F2P title. Given

this interest, two independent point-biserial correla-

tion analyses

6

were performed. To measure the will-

ingness to purchase within the game, this variable was

binary coded with 0 for ”no money spent” and 1 for

”money spent”. Hypothesis 3 suggested that players

high in parasocial love would be more willing to in-

vest money to further enhance the relationship with

their love interest. However, the first point-biserial

correlation found no relationship between both vari-

ables (r(400) = .064; p = .202). Consequently, play-

ers’ feelings for their love interest had no impact on

the willingness to spend money within MysMe, sug-

gesting other underlying purchase motivations not ex-

plored within this study. Thus, hypothesis 3 cannot be

supported.

The last hypothesis assumed that players high in

romantic loneliness would be more willing to invest

money to keep the fantasy of the relationship alive and

protect themselves against potential break-up experi-

ences (H4). Unlike assumed, the correlation analysis

revealed a weak but significant negative relationship

(r(400) = −.133; p = .007), suggesting that less ro-

mantically lonely individuals are more willing to in-

vest money within the game. Therefore, hypothesis 4

is refuted.

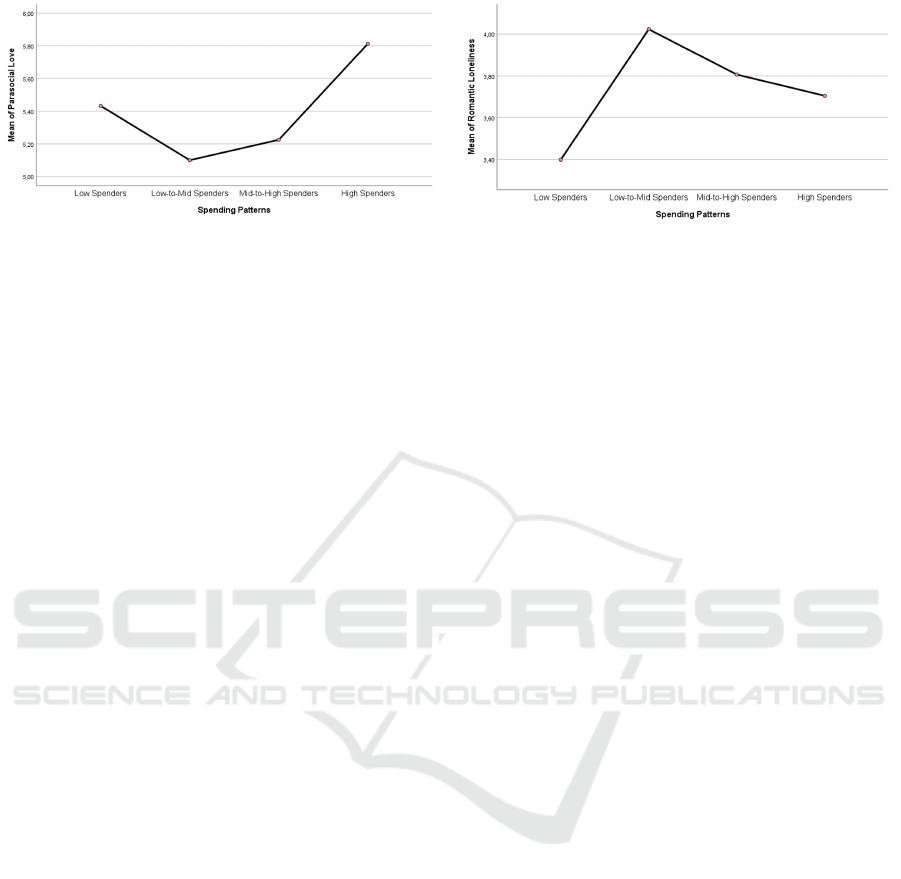

Despite neither of parasocial love nor romantic

loneliness being related to the willingness to invest

money, this study also looked at how either feeling in-

fluenced the actual spending patterns of players. For

this, paying players were first divided into four dif-

ferent spending groups: low spenders (less than 5

$), low-to-mid spenders (5 to 49.99 $), mid-to-high

spenders (50 to 149.99 $) and high spenders (150 $

and above). Next, two independent Welch-ANOVA

7

were performed to account for differences. The anal-

6

Although different ways to do a correlation between

metric and numeric variables are possible, point-biserial

correlation was chosen due to its easier interpretability.

7

Because Levene’s test could not assume equal vari-

ances for either variable (parasocial love: p = .038, roman-

tic loneliness: p = .002), the Welch-ANOVA was applied

for both analyses.

Yearning for Love: Exploring the Interplay of Parasocial Romantic Attachment, Loneliness, and Purchase Behavior Within Dating

Simulation Games

411

Table 1: Summary of Hypothesis Testing.

Hypothesis Statement Results

H1 Players high in romantic loneliness exhibit r = −.048 Rejected

stronger parasocial love for dating sim love interests. p = .336

H2 There is a difference in the relationship between romantic F(1, 398) = 0.27 Rejected

loneliness and parasocial love for dating and non-dating players. p = .60

H3 Players high in parasocial love are more likely to invest money r(400) = .064 Rejected

in dating simulation games. p = .202

H4 Players high in romantic loneliness are more likely to invest r(400) = −.133 Rejected

money in dating simulation games. p = .007

ysis identified significant differences when looking at

feelings of parasocial love and individual spending

patterns (F(3, 107.11) = 5.74, p < .001). More pre-

cisely, low-to-mid spenders (−.712;CI[−1.18, −.24])

and mid-to-high spenders (−.59;CI[−1.08, −.09])

showed significantly less parasocial love compared

to high spenders. In a similar vein, the corre-

sponding Welch-ANOVA also revealed significant

differences between levels of romantic loneliness and

spending patterns (F(3, 100.53) = 2.83, p = .042).

Specifically, low spenders scored significantly lower

on romantic loneliness than mid-to-high spenders

(−0.62;CI[−1.19, −.06]) as depicted by Figure 1.

5 DISCUSSION

This paper focused on the potential influence of ro-

mantic loneliness on the intensity of romantic feel-

ings for the fictional protagonists of the free-to-play

game MysMe – one of the first to address roman-

tic parasocial phenomena in the context of such dat-

ing simulation games. While it was assumed that the

romantic nature of dating sims would make paraso-

cial love for these characters particularly appealing

for romantically lonely players, findings suggest that

the opposite is true. Less romantically lonely play-

ers exhibit stronger feelings for their love interests.

This is consistent with a study done by (Hu et al.,

2021) who found a similar relationship when inquir-

ing about parasocial love with mass media characters.

It appears, then, that romantic parasocial compensa-

tion is no more likely to occur in interactive media

environments than in traditional ones. It might just

be that, despite the simulated reciprocity offered in

these games, most players remain aware that these

relationships are not real (Karhulahti and V

¨

alisalo,

2020). Therefore, such attachments might not be

deemed adequate to fulfill romantic desires. As a re-

sult, romantically lonely players may look for other,

real-life alternatives instead. Indeed, according to So-

cial Presence Theory (Short et al., 1976) people are

more inclined to turn to interpersonal bonds for their

relational needs rather than using mediated commu-

nication to satisfy them. The same may be true for

romantic needs. For less romantically lonely play-

ers, on the other hand, the appeal of such romantic

attachments might simply lie in their design. (Mal-

lon and Lynch, 2014) contend that it is natural for

players to develop meaningful emotional attachments

to non-playable game characters if these figures are

well-rounded, responsive, and able to change depend-

ing on players’ choices. Other factors such as physi-

cal and personal attraction, as well, have been found

as reasons to develop romantic feelings to game char-

acters (Coulson et al., 2012). In dating simulation

games, these factors greatly contribute to their suc-

cess. Moreover, with their romantic needs fulfilled,

such players may be generally more open to pursu-

ing these intimate attachments for what they are – an

easy and risk-free way to enjoy and indulge in differ-

ent romantic scenarios with a set of attractive char-

acters. All in all, the results further underpin the no-

tion that romantic parasocial bonds as complementary

relationships (Karhulahti and V

¨

alisalo, 2020; Wang

et al., 2008).

While we assumed that dating status would influ-

ence the relationship between romantic loneliness and

parasocial love, this assumption was not supported.

Instead, no significant differences were observed be-

tween dating and non-dating players. This finding is

intriguing as it contradicts research by (Greenwood

and Long, 2011) and (Liebers, 2022) who found sin-

gles to be generally more receptive to more intense

parasocial bonds. While surprising at first glance, the

little difference in the intensity of feelings between

both groups can be ascribed to the fact that parasocial

bonds are a natural part of the media experience. Af-

ter all, the virtual relationship between the players and

love interests develops gradually the more they get to

know each of them and their quirks. Moreover, they

offer (young) women a way to explore their roman-

tic relationships with little consequences or dangers

in real-life relationships. This is particularly impor-

tant as women tend to be more at risks when it comes

to exploring their sexual and romantic identity, es-

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

412

Figure 1: Mean differences of parasocial love and romantic loneliness by spending patterns.

pecially in early adolescence (Erickson and Dal Cin,

2018). Therefore, the relationships fostered in dat-

ing simulation games might be especially appealing

as they give players a sense of control over their de-

velopment that might be empowering and fulfilling.

Moreover, whereas single players might indeed derive

certain benefits from their romantic parasocial attach-

ments in the absence of a romantic partner (Adam and

Sizemore, 2013), dating participants may use these

relationships to spice up their day-to-day love life. As

explained above, dating simulation games often offer

a diverse cast of love interests, each with their distinct

personality. By engaging with them, players get to ex-

periment with different characters who not necessar-

ily have to be the kind of person they are committed to

in real-life (Beusman, 2016; Schwartz, 2018). More-

over, compared to their real-life partners, these love

interests typically lavish players with their undivided

attention as they do not need to concern themselves

with responsibilities common in daily life.

In terms of investing money in MysMe, players’

romantic feelings for a love interest did not relate to

their decision to spend money in-game as the relation-

ship was not significant. Given the large number of

reported paying players (69.2%), this might suggest

that players invested for reasons driven more by over-

all gameplay than the attachments themselves. How-

ever, when viewing the actual amount of money pay-

ing players had invested, a slightly different picture

emerged. Both low spenders (¡5 $) and high spenders

(¡ 150 $) showed significantly higher levels of paraso-

cial love, indicating at least some sort of interdepen-

dence. In comparison, low-to-mid (5 to 49.99 $)

and mid-to-high (50 to 149.99 $) spenders exhibited

overall fewer romantic feelings for their love interest,

though, that did not seem to hinder them from spend-

ing money in the game.

There are several explanations for this. On the

one hand, some players might not view purchasing

virtual goods in the game as a valuable way to en-

hance their virtual relationship despite their intensity

of feelings. While it is true that some content can only

be bought by investing real money, other content can

be unlocked by extending some effort towards collect-

ing the in-game currency during gameplay. Compared

to other games with similar business models, MysMe

allows players to do so relatively easy by participat-

ing in the daily chatrooms. As such, players high in

parasocial love might not be required to spend a lot of

money to achieve the desired outcome. On the other

hand, other players with strong feelings of parasocial

love might invest exceedingly more money to get the

full experience of the simulated relationship at a more

rapid pace. Impatience might play a role in this re-

spect. The desire to progress fast might be enough

of a motivator to disregard the amounts of money in-

vested because the gratifications achieved momentar-

ily make up for it. This might be especially true for

single-player games like MysMe where there is no

competition and thus no feelings of guilt or unfairness

when taking such shortcuts (Evans, 2016).

The overall level of romantic loneliness did re-

late to spending money in MysMe, albeit in an un-

expected way. Rather than greater romantic loneli-

ness, it was less romantically lonely players who were

more likely to spend money within the game. Consid-

ering the time and effort needed to complete routes

or unlock content in MysMe, and the fact that many

players were in a committed relationship, speeding up

gameplay or using money for convenience might be

the logical conclusion. Indeed, the excessive use of

mobile devices while in the presence of a romantic

partner can significantly impair and damage existing

relationships (Zhan et al., 2022). To avoid ignoring

the real-life partner without hampering the enjoyment

of the game might have less lonely players more will-

ing to invest real money in dating sims.

Additionally, more ambiguous findings emerged

for romantic loneliness when looking more closely at

the amount of money invested. Those indicating the

most romantic loneliness tended to have spent consid-

erably more money compared to players with lower

scores who only spent moderate sums of money (less

than 5 $). This insinuates that unfulfilled romantic

Yearning for Love: Exploring the Interplay of Parasocial Romantic Attachment, Loneliness, and Purchase Behavior Within Dating

Simulation Games

413

needs and the fear of losing the virtual relationship

do play their part in terms of purchasing decisions.

Albeit this might only be true for a selective group

of paying players. For these players, the absence of

a (fulfilling) romantic partner might trigger more in-

tense purchase behavior to sustain the gratifications

from the virtual relationship and avoid any unpleas-

ant repercussions upon its dissolution (Eyal and Co-

hen, 2006). Thereby, the emotional response to an

expected loss might be so intense that simply replay-

ing the game as usual without getting any additional

interactions out of it may no longer be sufficient.

6 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Amidst rising concerns about whether female players

flock to dating simulation games to compensate for

missing real-life romance, the present study explores

the role of romantic loneliness and dating status in de-

veloping romantic parasocial attachments. Moreover,

it is one of the first to address how these feelings in-

teract with the decision to invest real money into these

virtual relationships. For this purpose, an online sur-

vey among 402 female players of the viral mobile dat-

ing sim MysMe was conducted and evaluated. On the

question of which role the longing for romantic inti-

macy played in fostering romantic feelings for these

virtual characters, the general answer is none. Players

do not use these bonds to compensate for any void

in their love lives, joining findings of related stud-

ies on parasocial compensation among mass media

figures. While players, indeed, develop strong emo-

tionally meaningful attachments to their chosen vir-

tual lovers, unfulfilled romantic needs are not the cen-

tral motivator around doing so. Neither romantically

lonely nor non-dating players show more intense feel-

ings for these characters. Rather interestingly, there is

little to no difference in the overall intensity of paraso-

cial love between these groups, highlighting the need

for more qualitative research in this field. In-depth

interviews with dating and non-dating players of dat-

ing simulation games may provide more detailed in-

sights into what prompted them to indulge in these

simulated relationships to begin with. Furthermore,

exploring the impact of playing such games while in

a committed relationship might also be a fruitful new

avenue of research. Matters such as viewing such re-

lationships as cheating or feelings of jealousy of the

non-playing partner would certainly be interesting to

explore.

Despite the strong feelings many players exhibited

for the virtual characters in MysMe, these emotional

attachments have little impact on the willingness to

invest real money in the game. Though some more

heavily involved players show more intense spend-

ing behavior, the overall spending patterns are con-

flicting and do not allow for a conclusive interpreta-

tion. Similar findings are observed for romantic lone-

liness. While overall willingness to expend money

is more prominent for less romantically lonely peo-

ple, for paying players, more intense feelings of lone-

liness do prompt more excessive spending behavior

overall. Apparently, investing in the game offers ad-

ditional benefits to some players. As this study takes

an exploratory approach and no prior study has in-

quired about the hypothesized relationships, further

research is certainly needed before drawing any in-

ferences. Future studies might expand variables on

purchase behavior, asking what had prompted players

to initially invest in the game to gain a more thorough

understanding of paying motivations in this specific

niche. Tracing potential direct or indirect relations

to motifs recognized in studies on other free-to-play

environments, as well, may further provide valuable

insights into spending behavior.

Ultimately, this study points at the complexities in

the development of these one-sided romances while

also offering insights into the dating sim niche and

its players as a whole – with promising new areas of

research in the future. By understanding the allure of

this simulated romantic intimacy, scholars can gain an

idea of how people’s emotions intertwine with inter-

active media characters and how this shapes their ex-

periences and behaviors. Specifically, when it comes

to investing money. As dating simulation games con-

tinue to evolve, this might become increasingly im-

portant.

REFERENCES

Adam, A. and Sizemore, B. (2013). Parasocial romance: A

social exchange perspective. Interpersona: An Inter-

national Journal on Personal Relationships, 7(1):12–

25.

Adamczyk, K. (2016). An Investigation of Loneliness

and Perceived Social Support Among Single and

Partnered Young Adults. Current Psychology (New

Brunswick, N.J.), 35(4):674–689.

Baumeister, R. F. and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to

belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fun-

damental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin,

117(3):497–529.

Bernardon, S., Babb, K. A., Hakim-Larson, J., and Gragg,

M. (2011). Loneliness, attachment, and the perception

and use of social support in university students. Cana-

dian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadi-

enne des sciences du comportement, 43(1):40–51.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

414

Beusman, C. (2016). Meine sinnliche Reise in die Welt der

japanischen Dating-Sims. Accessed 11.06.2023.

Bortz, J. and Schuster, C. (2010). Statistik f

¨

ur Human-

und Sozialwissenschaftler: Limitierte Sonderausgabe.

Springer, 7th edition.

Branch, S. E., Wilson, K. M., and Agnew, C. R. (2013).

Committed to Oprah, Homer, or House: Using the

investment model to understand parasocial relation-

ships. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(2):96–

109.

Burgess, J. and Jones, C. (2020). ”I harbor strong feelings

for Tali despite her being a fictional character”: Inves-

tigating videogame players’ emotional attachments to

non-player characters. The International Journal of

Computer Game Research, 20(1):1–16.

Canary, D. J. and Spitzberg, B. H. (1993). Loneliness

and media gratifications. Communication Research,

20(6):800–821.

Caughey, J. L. (1986). Social relations with media figures.

In Gumpert, G. and Cathcart, R., editors, Intermedia:

Interpersonal communication in a media world, pages

219–252. Oxford University Press, New York, NY,

3rd edn edition.

Chory-Assad, R. M. and Yanen, A. (2005). Hopelessness

and loneliness as predictors of older adults’ involve-

ment with favorite television performers. Journal of

Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49(2):182–201.

Coulson, M., Barnett, J., Ferguson, C. J., and Gould, R. L.

(2012). Real feelings for virtual people: Emotional at-

tachments and interpersonal attraction in video games.

Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(3):176–184.

Cowley, R. (2018). China-only dating sim Love and Pro-

ducer generated $32 million in January 2018. Ac-

cessed 24.03.2023.

Davidson, R. (1993). Estimation and inference in econo-

metrics. Oxford University Press.

DiTommaso, E. and Spinner, B. (1993). The develop-

ment and initial validation of the Social and Emotional

Loneliness Scale for Adults (SELSA). Personality

and Individual Differences, 14(1):127–134.

D

¨

oring, N. (2013). Wie Medienpersonen Emotionen und

Selbstkonzept der Mediennutzer beeinflussen. In

Schweiger, W. and Fahr, A., editors, Handbuch

Medienwirkungsforschung, pages 295–310. Springer

Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden.

Erickson, S. E. and Dal Cin, S. (2018). Romantic Paraso-

cial Attachments and the Development of Roman-

tic Scripts, Schemas and Beliefs among Adolescents.

Media Psychology, 21(1):111–136.

Erickson, S. E., Harrison, K., and Dal Cin, S. (2018). To-

ward a Multi-Dimensional Model of Adolescent Ro-

mantic Parasocial Attachment. Communication The-

ory, 28(3):376–399.

Evans, E. (2016). The economics of free. Convergence:

The International Journal of Research into New Me-

dia Technologies, 22(6):563–580.

Eyal, K. and Cohen, J. (2006). When good friends say good-

bye: A parasocial breakup study. Journal of Broad-

casting & Electronic Media, 50(3):502–523.

Field, A. (2024). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS

statistics. Sage publications limited.

Ganzon, S. C. (2019). Investing Time for Your In-Game

Boyfriends and BFFs: Time as Commodity and the

Simulation of Emotional Labor in Mystic Messenger.

Games and Culture, 14(2):139–153.

Ganzon, S. C. (2022). Playing at Romance: Otome Games,

Globalization and Postfeminist Media Cultures. Doc-

tor of philosophy, Concordia University, Montreal,

Quebec.

Gardner, W. and Knowles, M. (2008). Love makes you real:

Favorite television characters are perceived as ”real”

in a social facilitation paradigm. Social Cognition,

26(2):156–168.

Gleich, U. (1997). Parasocial interaction with people on the

screen. New horizons in media psychology: Research

cooperation and projects in Europe, pages 35–55.

Google Play (2023). Mystic messenger. Accessed

08.06.2023.

Greenwood, D. N. and Long, C. R. (2011). Attachment,

belongingness needs, and relationship status predict

imagined intimacy with media figures. Communica-

tion Research, 38(2):278–297.

Hartmann, T. (2016a). Mass communication and para-

social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a dis-

tance (by donald horton and r. richard wohl (1956)).

In Potthoff, M., editor, Schl

¨

usselwerke der Medien-

wirkungsforschung, pages 75–84. Springer Fachme-

dien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden.

Hartmann, T. (2016b). Parasocial interaction, parasocial re-

lationships, and well-being. In The Routledge hand-

book of media use and well-being, pages 131–144.

Routledge.

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation,

and conditional process analysis: A regression-based

approach. Guilford publications.

Hirschman, E. C. (1983). Predictors of self-projection, fan-

tasy fulfillment, and escapism. Journal of Social Psy-

chology, 120(1):63–76.

Horton, D. and Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication

and parasocial interaction: Observations on intimacy

at a distance. Psychiatry, 19(3):215–229.

Hu, M., Zhang, B., Shen, Y., Guo, J., and Wang, S. (2021).

Dancing on my own: Parasocial love, romantic lone-

liness, and imagined interaction. Imagination, Cog-

nition and Personality: Consciousness in Theory, Re-

search, and Clinical Practice, pages 1–24.

Huang, Z. (2018). Chinese women are spending millions of

dollars on virtual boyfriends. Accessed 15.08.2023.

Karhulahti, V.-M. and V

¨

alisalo, T. (2020). Fictosexuality,

fictoromance, and fictophilia: A qualitative study of

love and desire for fictional characters. Frontiers in

Psychology, 11.

Liebers, N. (2022). Unfulfilled romantic needs: Effects of

relationship status, presence of romantic partners, and

relationship satisfaction on romantic parasocial phe-

nomena. Psychology of Popular Media, 11(2):237–

247. Advance online publication.

Liebers, N. and Schramm, H. (2019). Parasocial interac-

tions and relationships with media characters: An in-

Yearning for Love: Exploring the Interplay of Parasocial Romantic Attachment, Loneliness, and Purchase Behavior Within Dating

Simulation Games

415

ventory of 60 years of research. Communication Re-

search Trends, 38(2):4–31.

Mallon, B. and Lynch, R. (2014). Stimulating psychological

attachments in narrative games. Simulation & Gam-

ing, 45(4-5):508–527.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., and Cook, J. M. (2001).

Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. An-

nual review of sociology, 27(1):415–444.

Meyrowitz, J. (1994). The life and death of media friends:

New genres of intimacy and mourning. In Cathart, R.

and Drucker, S., editors, American heroes in a media

age, pages 52–81. Cresskill, NJ.

Rubin, A. M., Perse, E. M., and Powell, R. A. (1985).

Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and local televi-

sion news viewing. Human Communication Research,

12(2):155–180.

Russon, M.-A. (2020). 22 Million Women Worldwide

Hooked on ’Otome’ Romantic Dating Simulator

Games. Accessed 23.04.2023.

Saito, K. (2021). From Novels to Video Games: Romantic

Love and Narrative Form in Japanese Visual Novels

and Romance Adventure Games. Arts, 10(42):1–18.

Schiappa, E., Allen, M., and Gregg, P. B. (2011). Paraso-

cial relationships and television: A meta-analysis of

the effects. In Preiss, R. W., Gayle, B. M., Bur-

rell, N., Allen, M., and Bryant, J., editors, Mass me-

dia effects research: Advances through meta-analysis,

pages 301–314. New York, London: Routledge.

Schwartz, O. (2018). Love in the time of AI: meet the peo-

ple falling for scripted robots. Accessed 25.05.2022.

Short, J., Williams, E., and Christie, B. (1976). Social psy-

chology of telecommunications. London: John Wiley.

Sphancer, N. (2014). Laws of Attraction: How Do We

Select a Life Partner?: What we know, and don’t

know, about the process of mate selection. Accessed

15.08.2023.

Taylor, E. (2007). Dating-simulation games: Leisure

and gaming of Japanese youth culture. Accessed

11.09.2021.

Tukachinsky, R. (2010). Para-romantic love and para-

friendships: Development and assessment of multiple

parasocial relationships scale. American Journal of

Media Psychology, 3:73–94.

Tukachinsky, R. and Stever, G. (2019). Theorizing De-

velopment of Parasocial Experiences. Accessed

01.09.2021.

Turner, J. R. (1993). Interpersonal and psychologi-

cal predictors of parasocial interaction with differ-

ent television performers. Communication Quarterly,

41(4):443–453.

Voltage Inc. (2023a). Company: Business. https://www-

en.voltage.co.jp/company/business/. Accessed

03.04.2023.

Voltage Inc. (2023b). Financial highlights: Earnings high-

light. https://www-en.voltage.co.jp/ir/highlight/. Ac-

cessed 03.04.2023.

Waern, A. (2010). ”I’m in love with someone that doesn’t

exist!!” Bleed in the context of a Computer Game.

In DiGRA Nordic ’10: Proceedings of the 2010 In-

ternational DiGRA Nordic Conference: Experiencing

Games: Games, Play, and Players, pages 1–7.

Wang, Q., Fink, E. L., and Cai, D. A. (2008). Loneli-

ness, gender, and parasocial interaction: A uses and

gratifications approach. Communication Quarterly,

56(1):87–109.

Zhan, S., Shrestha, S., and Zhong, N. (2022). Romantic re-

lationship satisfaction and phubbing: The role of lone-

liness and empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13:1–12.

ICEIS 2025 - 27th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

416