Student Views in AI Ethics and Social Impact

Tudor-Dan Mihoc

a

, Manuela-Andreea Petrescu

b

and Emilia-Loredana Pop

c

Department of Computer Science, Babes Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Keywords:

Computer Science, AI, Ethics, Study, Students, Opinion, Threat, Benefit, Survey.

Abstract:

An investigation, from a gender perspective, of how students view the ethical implications and societal effects

of artificial intelligence is conducted, examining concepts that could have a big influence on how artificial

intelligence may be taught in the future. For this, we conducted a survey on a cohort of 230 second-year

computer science students to reveal their opinions. The results revealed that AI, from the student’s perspective,

will significantly impact daily life, particularly in areas such as medicine, education, or media. Men are

more aware of potential changes in Computer Science, autonomous driving, image and video processing,

and chatbot usage, while women mention more the impact on social media. Both men and women perceive

potential threats in the same manner, with men more aware of war, AI-controlled drones, terrain recognition,

and information war. Women seem to have a stronger tendency towards ethical considerations and helping

others.

1 INTRODUCTION

The exposure of AI in the media causes deep unrest in

society about the future of this technology. Suddenly,

more aware of AI tools (Vieweg, 2021), people be-

gin to debate their implications on the economy, the

job market, education, and, not least, ethical issues.

Researchers in (Ouchchy et al., 2020) examine and

categorize how these topics are portrayed in the press

to better understand how this representation could af-

fect public opinion. According to their findings, the

media coverage is still on the surface but has a realis-

tic and pragmatic perspective. Other topics related to

certain AI methods of information retrieval exposed

are: privacy, transparency, biases, censorship, filter

bubbles, security, accessibility, data handling, surveil-

lance, job displacement, or data ownership (Boren-

stein and Howard, 2021).

There is concern that these systems can reinforce

or magnify the biases present in the training data, re-

sulting in injustice and discrimination. Furthermore,

the processing of user data raises privacy problems

because it can lead to data breaches, illegal access,

and surveillance (Banciu and C

ˆ

ırnu, 2022).

Students, as future workers and decision makers,

should have a high level of understanding of AI ethics,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2693-1148

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9537-1466

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4737-4080

which will help them design and implement AI sys-

tems ethically. Therefore, an insight into students’

awareness of ethical concerns related to AI is very im-

portant.

In the study (Cernadas and Calvo-Iglesias, 2020)

the author acknowledges the existence of gender dis-

criminatory biases in the development of students. In

order to limit these, he underlines the need to intro-

duce gender perspectives in studies.

Such disparities can also be found in other coun-

tries. In some of Romania’s largest universities, ap-

proximately 31% of computer science students are

female. We asked related data to the number of

women/men that graduated computer science using a

law of transparency that states that public institutions

must provide any public information.

There have been studies (Pop and Coroiu, 2024;

Pop, 2024) on the inclination of middle school stu-

dents to technical education education using machine

learning, but little research has been conducted on the

students’ inclination to actually use and perfect AI.

A survey could reveal the knowledge gaps and

capture the diverse perspectives on this topic with re-

spect to gender. The purpose of the study was to

contribute to academic research on AI ethics and can

provide empirical evidence for scholarly publications,

furthering the understanding of ethical considerations

in AI.

In order to address these topics, we defined the

research questions as:

26

Mihoc, T.-D., Petrescu, M.-A. and Pop, E.-L.

Student Views in AI Ethics and Social Impact.

DOI: 10.5220/0013139500003932

In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2025) - Volume 1, pages 26-35

ISBN: 978-989-758-746-7; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

⋆ Which domains will be most affected by AI?

gender-based perspective.

⋆ What are the ethical considerations related to the

potential threats associated with Artificial Intelli-

gence?

⋆ Who is willing to sacrifice ethical values for

money and social status? Is there a difference be-

tween how women and men perceive them?

We run a survey among students studying computer

science in their second year at Babes-Bolyai Univer-

sity, Romania, to get their opinions. We highlight

that at the end of the second term, the students have

a fundamental understanding of artificial intelligence.

They were knowledgeable with rule-based systems,

machine learning, decision trees, artificial neural net-

works, deep learning, intelligent systems, support

vector machines, clustering, and problem solving as

a search. Throughout the semester, a lecture focused

on fraud prevention and AI-related ethical issues. We

highlighted sensitive topics and approaches from the

perspective of an IT expert, using examples of fake

news and the techniques used to create them, as well

as how an AI could be tainted and biased through the

training database. The survey questions were related

to the lecture topics, allowing us to assess students’

understanding of the material as well as their thoughts

on the ethical implications of AI.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Gender disparities related to IT and, more recently,

artificial intelligence have been the subject of several

studies that have surfaced over the years.

The impact of artificial intelligence on female

employment is multifaceted. Men and women are

disproportionately affected by industrial growth and

platformization, driving the latter out of the labor

force (Mohla et al., 2021). A possible reason for per-

petuating stereotypes and discrimination is the dimin-

ished importance of women in AI development and

implementation. The need to address the gender gap

before it becomes pervasive and embedded in AI cul-

ture was highlighted by (Roopaei et al., 2021).

According to (Abdullah, 2019), AI is seen as

a complex potential threat that could affect human

behavior, replace jobs, and generate economic in-

equality. Cultural differences, discrimination, and in-

discriminate use of computing resources are just a

few ethical challenges that exacerbate these threats

(Baeza-Yates, 2022). In (Fisher and Fisher, 2023) the

authors call for increased cooperation and considera-

tion of human interests in the development of artificial

intelligence. They pleaded for legislative approaches

that address these concerns.

More ethical concerns about AI, such as bias, un-

employment, and socioeconomic inequality, are also

raised by (Green, 2018), who also emphasizes the

need for a more thorough analysis of these problems.

There are differences in the ethical decision mod-

els used by men and women (Schminke and Am-

brose, 1997), with a significant difference in the way

men and women perceive and prioritize ethical values

in different scenarios. When financial gain and so-

cial status are involved, research consistently shows

that women are more averse to ethical compromises

(Kennedy et al., 2013; Kennedy et al., 2014) than

men. They tend to associate business with immorality

more than men, and this aversion seems to be related

to their lower representation in high-ranking business

positions.

While the underrepresentation of women and mi-

norities in the IT workforce is a problem, their inclu-

sion may offer a way to address the industry’s skills

gap (Gallivan et al., 2006).

Particularly in AI jobs, there are large variations

between different groups. (Jakesch et al., 2022) dis-

covered that AI practitioners had different values in

mind than the broader public, with black and female

respondents giving ethical AI ideals more weight.

This aligns with the findings of (Callas, 1992), who

indicated that female workers were more inclined to

consider discriminatory actions to be morally wrong.

According to (Rothenberger et al., 2019; Zhou et al.,

2020), ethical standards for AI are crucial and may

reflect the values that black and female respondents

found most important.

(Cave et al., 2023; Brown et al., 2022; Yarger

et al., 2020) also found similar findings, demonstrat-

ing that minorities and women are notably underrep-

resented in AI development jobs. One major prob-

lem with AI teams is the attrition of individuals with

marginalized identities; many people leave because of

the culture and environment of these teams. This is-

sue is made worse by algorithmic bias in talent acqui-

sition tools, which keeps hiring practices unfair.

These studies collectively suggest that AI’s influ-

ence on gender is multifaceted, with the potential to

exacerbate existing inequalities.

With this research, we want to have a better under-

standing of these issues in relation to gender. By ad-

dressing the research questions, we want to determine

the students’ areas of interest in ethical concerns.

Student Views in AI Ethics and Social Impact

27

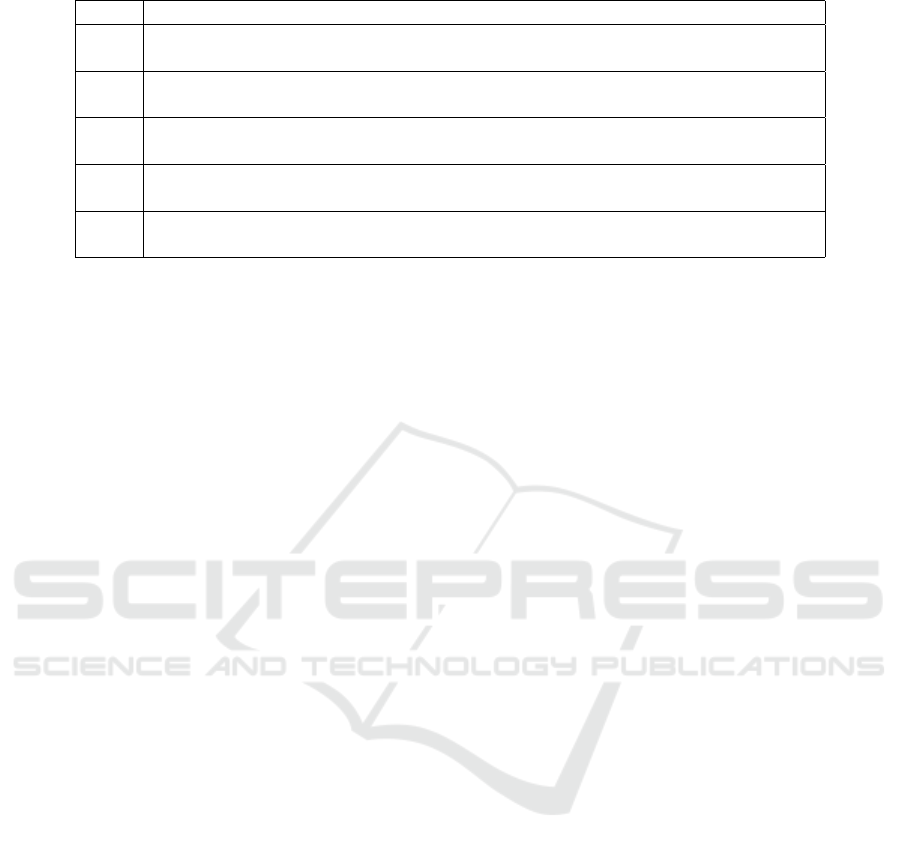

Table 1: Survey Questions.

Q1 Please specify your gender. Choice of male, female, or I prefer not to answer.

Q2 In which domains do you think Artificial Intelligence will have the greatest impact

and why? (Mention at least 3)

Q3 Which are considered the main benefits related to Artificial Intelligence that

might appear in the next 3 years?

Q4 Which are considered the main risks related to Artificial Intelligence that

might appear in the next 3 years?

Q5 Which are the main reasons you do NOT like a career in Artificial

Intelligence?

Q6 Which are the main reasons you would like to have a career in

Artificial Intelligence?

3 STUDY DESIGN

We used the guidelines provided by (Runeson and

H

¨

ost, 2009) to organize this research in accordance

with the norms of the scientific community, as stated

in (Ralph, 2021). We first determined the study’s

scope before deciding on the methodology.

Scope: The purpose of the study was to evaluate

students’ attitudes about the advancement of artificial

intelligence, as well as their interest in learning more

about and working in this field with respect to gender

identity.

Who: Second-year students from computer sci-

ence departments who took an introductory AI course

constituted the group of participants.

When: At the conclusion of the semester, we

asked the students to take a survey to find out their

perspectives.

How to: We used a hybrid strategy, analyzing the

gathered replies both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Observations: Analysing the answers, we found

out that students have concerns about the ethics of AI,

so we performed an analysis to find out AI related

ethics interests.

Participation: Participation in the study was vol-

untary, and the survey was anonymous, so we could

not map participants with their answers.

3.1 Survey Design

After we established the purpose of the investiga-

tion and formulated the research questions, we pre-

pared the survey questions. The process was an iter-

ative one; first, we elaborated on a set of questions,

then two authors discussed, proposed, and validated

changes to the form and structure of the questions.

The second draft was discussed with the third author,

and we agreed on the final versions of the questions.

We decided to add questions that we will not use in

the study, for example, questions Q3 and Q6. The

purpose of these questions was to prevent bias in the

received responses and to ask for positive and nega-

tive aspects.

We decided to use both closed and open questions.

The first question was used to determine the groups

and categories of participants (men versus women).

The other questions were used to encourage students

to freely express their opinions, since open-ended

questions can offer valuable insights into the students’

perspectives and perceptions. The questions asked in

the survey are listed in Table 1.

3.2 Participants

The target audience for our survey was formed by

second-year computer science students. As a result,

the set of participants consisted of 230 individuals, of

whom 198 agreed to participate in the study. Seven

of them did not wish to disclose their gender, 119 of

them were men and 72 women. Given the size of the

sample and the fact that the ratio of female partici-

pants is similar to the ratio of female students enrolled

in the faculty, we may conclude that the study’s fe-

male representation is statistically significant.

3.3 Methodology

The following methodologies used in this study are

consistent with those used in previous research efforts

(Petrescu and Motogna, 2023; Motogna. et al., 2021).

At the end of the second semester, we conducted

a survey that included open and closed-ended items.

Accountable questions facilitate the work with and in-

terpretation of the data, whereas open questions lead

to a greater degree of comprehension. The analy-

sis and interpretation of the responses to open ques-

tions were carried out using quantitative approaches.

The questionnaire surveys met the accepted empirical

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

28

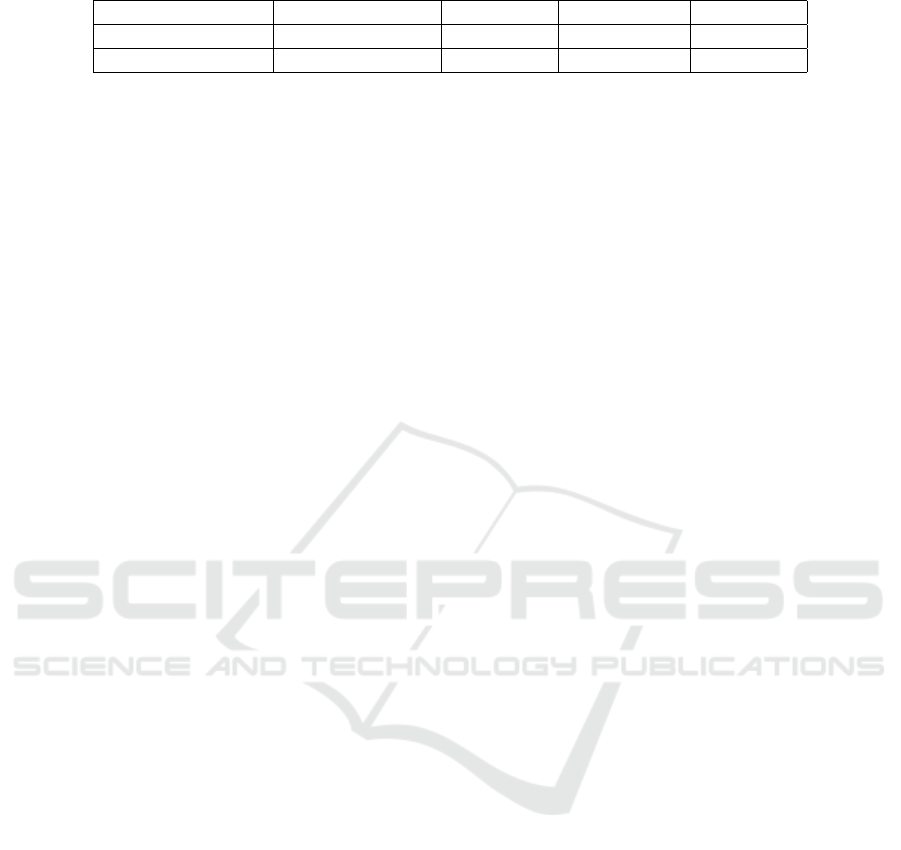

Table 2: Key item classes percentages for Data Processing.

Data Processing Data Processing Investing Economics Marketing

Men 7.81% 7.03% 5.47% 6.25%

Women 7.69% 8.97% 5.13% 5.13%

community norms (Ralph, 2021). Thematic analysis

was used for text interpretation, following the guide-

lines provided in (Braun et al., 2019). We applied the-

matic analysis using the following subsequent stages:

1. Two researchers independently attempted to

identify codes or key items within the text.

2. These key items were divided into classes ac-

cording to the frequently seen themes or cate-

gories. Those with low appearance frequency

will be reassigned to larger classes using tech-

niques such as generalization, elimination, and

reassignment.

3. The last step was a comprehensive debate

among all authors, so a certain degree of con-

fidence is achieved in the methodology. In the

discussions, reviews of several topics, represen-

tations, and supporting data for the categoriza-

tion procedure were included.

We computed the frequency of the important

terms. Even if some responses from students were

extremely succinct, many others included up to five

phrases or justifications. As a result, a response can

contain more items or important keys. A direct con-

sequence is that, in our analyses, the total cumulative

percentages will exceed 100%.

3.4 Data Collection

We proposed the questions set in English, as their line

of study is English based. The purpose of this choice

was to minimize the possible threats resulting from

translation. The information from the responses was

collected exactly as we received it, without any ma-

nipulation.

The students received a link to the anonymous sur-

vey via their MSTeams faculty account and were pro-

vided with enough time to ensure that their comments

were not too brief or non-existent.

4 RESULTS

In this section, we analyze the data collected and out-

line the results of student surveys. We took into ac-

count the different gender perspectives when we elab-

orated our analysis. We received 72 responses from

students who identified themselves as women, and we

considered it a representative number to have valid re-

sults. When we calculated the results, we computed

the prevalence of key items in women’s responses to

the total number of women, not the total number of

participants in the study.

When we asked students to mention at least three

domains (Q1), we had a couple of responses that men-

tioned four domains, there were three responses that

did not mention any domain, all the other students

mentioned two or three areas, some of them proving

details and explanations. We selected the key items,

classified and summarized them, and computed the

appearance percentages. Due to this process, the sum

of the percentages exceeds 100%. Responses to the

other survey questions were treated in the same way,

as each answer could contain zero, one, or more key

items, so the total percentages of prevalence of key

elements exceed 100%.

4.1 Q1: Which Domains Will Be Most

Affected by AI? Gender Based

Perspective?

To find the answer to this question, we used the an-

swers provided by the students to the survey question:

”In which domains do you think Artificial Intelligence

will have the greatest impact and why? (Mention at

least 3)”.

In the perception of the students, the domains with

the greatest impact that scored more than 10% of

their responses were medicine, education, program-

ming/computer science (CS), industries, and jobs that

involve repetitive tasks and autonomous driving. For

the domains most affected, there is no significant dif-

ference between the perceptions of men and women,

as can be seen in Figure 1, only three participants did

not answer this question.

Medicine was the domain most mentioned, scor-

ing above 50% for both men and women: ”health

care (detecting diseases, finding the best treatment,

etc.)”, ”I think AI will have the greatest impact in

medicine, in recognizing flaws unseen by the human

eye & in predictions of many kinds”. A larger differ-

ence appeared for the programming/computer sci-

ence domain, considered to be impacted by 30.47%

men and 21.79% women, ”Programming - helping

developers with repetitive code”, ”write code eas-

ier”, ”find errors such as missing coma”, ”in test-

Student Views in AI Ethics and Social Impact

29

Table 3: Key item classes percentages for Automatization.

AM Engineering Robots Research Physics Architecture Astronomy

Men 3.13% 3.91% 1.56% 1.56% 3.91% 2.34%

Women 7.69% 3.85% 2.56% 2.56% 3.85% 0.00%

Figure 1: Domains affected by AI. Gender Perspective.

ing”. A larger difference, more than 10% appears

to be related to autonomous driving, men seem to

be more interested in AI’s influence, they specify this

domain in a percent of 21.88% compared to women

10.26%: ”In the automotive industry, with regard to

cars that drive themselves”, ”self driving cars”. Ed-

ucation is mentioned more by women, but the differ-

ence is smaller compared to previous domains; only

about 4.55% women mention education more com-

pared to men: ”education as virtual tutoring will be

new thing”, ”Learning: you can access all knowledge

with AI”.

The rest of the domain were less prevalent in the

student’s answers, obtaining less than 10% and we

group them by categories based on the main charac-

teristics: automatization, the capacity to process large

amounts of data, and the capacity to generate content.

Large Data Processing Capabilities. In their opin-

ion, with the ability to process large amounts of data,

AI can have an impact in many areas, from analyz-

ing market trends and statistics to making predictions

for the stock market and betting: ”Identifying mar-

ket trends and strategies (economy)”, ”Data analysis,

works easily with large data”, ”Stock market predic-

tion, obviously”, ”Betting (sports, betting)”. Also,

concerns about marketing appear: ”because it is eas-

ier to detect patterns” in people’s behavior. A partic-

ular response synthesized this aspect: ”I think it will

have the greatest impact on education, data process-

ing, and research because it has access to information

beyond a single person’s capacity”. As shown in Ta-

ble 2, both genders fairly mentioned these aspects.

Automatization. (AM). An answer stated that ”Au-

tomatization of everyday tasks, can be done better

by AI than by humans”, either if we are referring to

”Surgery domain - great robots for operations” or to

”repetitive and boring tasks”. There are no signifi-

cant gender differences in perceptions, as can be seen

in Table 3.

Content Generation. A specific characteristic of

some AI tools is their ability to generate new con-

tent in terms of art, music, photo, and video editing

and processing. In art ”because it can generate high

quality free photos” or ”generate an image based on

description”, in ”design by generating images, pat-

terns or logos”, in fact ”In the creative industry (im-

ages, videos, music, etc.), the linguistic/news industry

(articles, translations, etc.)”. Music and even fash-

ion were mentioned: ”music: you can create music

with AI”, ”fashion: you can use different AI to create

clothes”. Men mention chatbots more compared to

women: ” Internet bots - easy to write text that looks

written by a human”, women mentioned more media

and social media: ”in algorithms used by social me-

dia platforms and in the video game industry because

it could learn about human behavior”.

Ethics Related Concerns. Some responses revealed

concerns related to mass manipulation through the de-

tection and use of patterns in people’s behavior. In

the view of the students, AI poses threats through ad-

vanced processing and generation of multimedia con-

tent (video, image, or audio) – ”deep fakes, it is a ma-

jor problem if they become hard to detect”. The use

of artificial intelligence in communication and social

media can have an impact on governments, wars, and

politics: ”politics because the generation of different

fake videos leads to disinformation”. Male partici-

pants also mentioned the use of drones, war recogni-

tion, and fighting. Although the question had a differ-

ent scope, there were responses concerned about pos-

sible job replacements since automation could elimi-

nate repetitive jobs: ”IT, in testing; I think it will be

the first job that will disappear”, ”industrial implies

that robots could replace people”.

Q1 Conclusion. The domains mentioned in the re-

sponses were diverse, suggesting that AI will have a

non-negligible impact on daily life. It was interesting

to analyze the fact that the domains most present in

the answers were the domains where there was a lot of

progress in AI: medicine, education, or photo/video

processing and generating.

In a general view, there are no significant differ-

ences between men’s and women’s perceptions re-

lated to the most affected domains; however, men

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

30

Table 4: Key item classes percentages for Content Generation.

Creation Art Text Video/photo (Social) Chatbots

generation editing Media

Men 6.25% 4.69% 8.59% 4.69% 10.94%

Women 5.13% 1.28% 3.85% 7.69% 2.56%

seem more aware of the potential changes in Com-

puter Science, autonomous driving, image and video

processing, and chatbot usage (either to replace jobs

or to be used in personalized learning). Women men-

tion, compared to men, only the impact on social me-

dia.

4.2 Q2: What Are the Ethical

Considerations Related to the

Potential Threats Associated with

Artificial Intelligence?

Following the analysis of the responses received,

we classified the key items into classes, resulting in

five main classes of threats: economic, information-

related, general, apocalyptic fear, and absence of

risks. Additionally, there were students who did not

respond to this question or indicated that they were

indifferent to it. A set of responses, 5.24% of them,

emphasized the need for regulations in the field of ar-

tificial intelligence. A rather significant percentage of

23.03% of students did not answer to this question

and stated that they consider AI not to pose any risks

2.45% and other 1.47% mentioned that they don’t

care. We designated this question as optional to avoid

introducing bias, as we did not want to force students

to respond if they had not considered the implications

of AI. The main threats identified by us were related

to economic issues, misinformation and fake news,

ethical concerns, the military, the loss of human abil-

ities, and becoming uncontrolled. The gender-based

concerns are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Major threats due to AI. Gender Perspective.

Economic Threats. are represented by a major cat-

egory: job cuts due to AI 26.56% men and 34.25%

women, the possible replacement of the artist’s work,

which was mentioned separately in 4.69% men’s re-

sponses and 1.37% women’s responses. Job cuts are

exemplified in responses such as: ”loss of jobs due

to human replacement by robots”, ”Job loss maybe

in programming” and even in creative domains such

as art: ”replacing artists” work or ”destruction of

multiple career paths (arts, writing currently endan-

gered)”. We got some responses that take into con-

sideration even ”market manipulation”, but in terms

of prevalence, responses that mention other domains

are rare.

Misinformation. Misinformation is the second most

mentioned threat, with a total of 10.16% men and

4.11% women. Separately, the threat of fake news

was mentioned by 10.94% of men and 6.85% of

women. AI can facilitate ”fake news spreading”, also

”misinformation will be more easily achieved”, and

”deep fake that becomes more and more convincing”.

Ethical Concerns. related to AI are mentioned as

ethical implications by 5.48% women and 8.59%

men, concerns related to copyright and/or plagiarism,

and a generic ”bad influence or ”bad direction” men-

tioned by 6.85% women and 5.47% men.

Ethical implications are mentioned in a general

manner, often quite succinct: ”the problem of ethic”,

”ethics concerns”, or ”I think there will be le-

gal and moral implications”, others offer more de-

tails: there is ”one enormous risk is that AI will be

needed for unethical or malicious purposes”. Pla-

giarism is mentioned as ”copyright of train data,

defamation, ethical concerns”, ”Art plagiarism, de-

commissioning artists, intellectual property theft (in-

tentional or not)”.

Military. The use of AI for military purposes ap-

pears in more than 14% of the answers, mentioned

by men and women in relatively similar percentages:

14.84% men versus 10.96% women: ”Use in mili-

tary, become smarter than humans, become incontrol-

lable”, ”Military: can lead to mass destruction”, can

be used for :”political biases” and ”propaganda. You

can already find on the internet deep fake of presi-

dents”. Protecting information in the information war

is essential, and AI can make a change at individual

levels: ”privacy issues, surveillance”, ”ethical con-

cerns regarding personal information and integrity”

Student Views in AI Ethics and Social Impact

31

or at mass levels: ,”It could get too much access to

important features”, it could ”leak dangerous infor-

mation”, and provide a ”better control and influences

over masses”.

There is a threat that AI could become uncon-

trolled, 12.50% men and 9.59% women expressed

this concern; they mention ”Self-improvement of al-

gorithms, to the point where control is lost”, and that

AI could ”become self-conscious”.

The last concern mentioned by students is not re-

lated to ethics but more to loss of human abilities

10.16% men and 15.07% women referred to it: ’De-

crease in the level of intelligence of humanity”,” We

can become dependent on it and lose our ability to

think”.

Conclusion. Men and women perceive potential

threats relatively in the same manner; even if the men

are more aware of the destructive character, they men-

tion war, AI controlled drones, terrain recognition, or

informational war in terms of sensitive information

leakage. In addition, men appear to be more aware of

the phenomenon of fake news and disinformation.

4.3 Q3: Who Is Willing to Sacrifice

Ethical Values for Money and Social

Status? Is There a Difference

Between How Women and Men

Perceive Them?

When people are asked about themselves, they often

respond how they would like to be or act (Rogers,

1966), so instead of asking if they would give up

financial benefits and status for ethical reasons, we

asked them to provide reasons for which they would

follow or not a career path in AI. If the number of

students who did not answer the previous questions

was relatively small, in these cases a larger number

of students had chosen not to answer or had clearly

specified that they did not know. When asked to give

reasons for not working in AI, 21.92% women and

34.11% men did not give any reason, and 17.81%

women and 6.98% stated that they want another ca-

reer. When asked for reasons to work in AI, 28.77%

women and 35.16% men did not provide reasons,

since the other 15.07% women and 9.38% men clearly

specified that they do not want a career in AI.

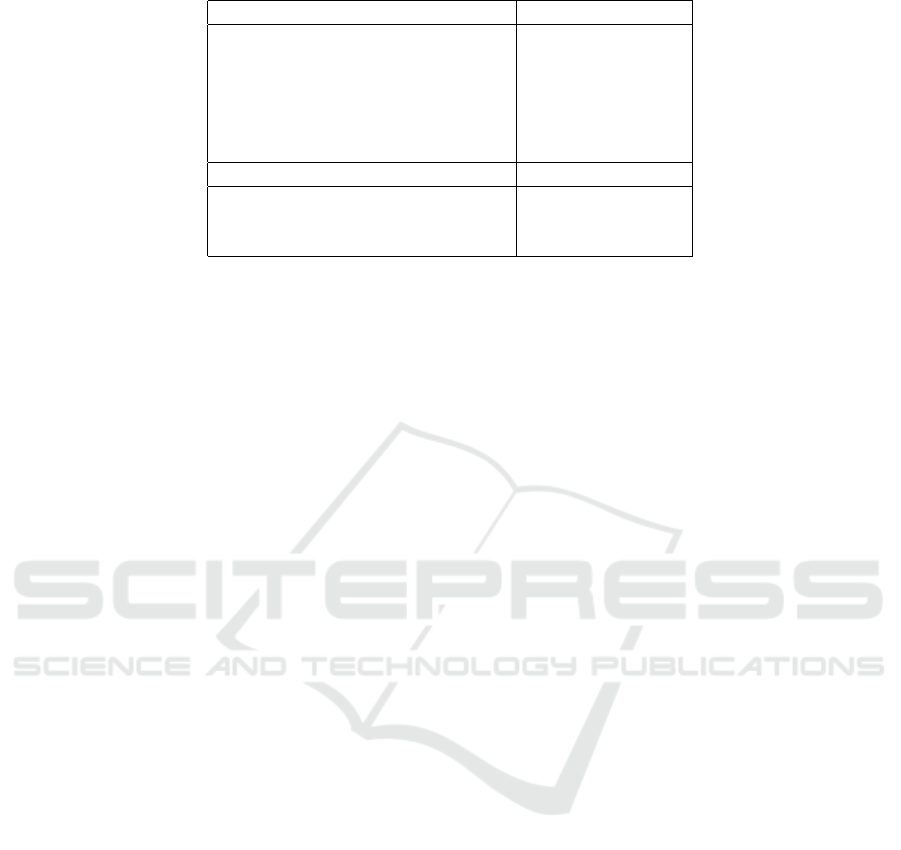

We grouped the items in the responses into two

large categories: ethical and non-ethical reasons. The

non-ethical reasons can be classified into financial and

non-financial reasons, summarizing more than 45%

for both men and women for both questions. In Table

5 we can see the key items for these non-financial per-

sonal reasons for choosing or not choosing to work in

an AI project for men versus women.

The non-ethical reasons are mostly financial - the

number of jobs and the opportunities to work in AI,

the pay for such a job. Men are more interested in

these aspects 18.75% compared to 12.33% women:

”Current lack of AI-focused jobs that allow transi-

tioning between workplaces for non-seniors.”, ”Hard

to get it”,”it has a very right chance that it will not

pay well because you gotta be on top”.

Ethical reasons are present in 13.70% of the

women’s responses and 10.08% in the men’s re-

sponses. Some perceive that AI is heading in a bad

direction 6.85% women versus 3.88% men, and some

believe that there are moral problems 4.11% women

versus 3.88% men. The students who clearly specify

that they do not want to contribute to AI’s develop-

ment due to ethical reasons or because the fact job

cuts and the effect on the people are 2.72% women

and 2.33% men.

Results Discussion.

There are no significant differences between gen-

ders in students’ perceptions related to beliefs and

perceptions, although there are some minor differ-

ences between men and women regarding the mention

of more frequent war fair, inaccurate information, fi-

nancial aspects, and ethical reasons.

Both men and women mentioned that the domains

most affected by AI development are the domains that

are already using AI (medicine, art, military, automa-

tion). A notable difference between men and women

appears only in fake news propagation and disinfor-

mation, aspects most mentioned by men. Women

mention loss of human abilities reasons more than

men. When asked about the reasons for a career in

AI, women more mentioned the desire to help: 9.59%

vs 6.25%: ”I could save people from a rare disease”,

”To help people with this technology in each aspect

of life to make a lot of comfort in society and help the

planet be more healthy”. Another difference is the

fact that men are more preoccupied by the financial

aspects (number of job opportunities and money) and

they are less preoccupied about ethics, compared to

women, who are more preoccupied about ethics, they

want more ”to help”.

5 THREATS TO VALIDITY

Through the analysis and application of the commu-

nity standards outlined in (Ralph, 2021), our objec-

tive was to minimize any possible risks. Similar prac-

tices have also been applied in other research pa-

pers, as in (Petrescu et al., 2023; Kiger and Varpio,

2020). We also mitigated the potential threats to va-

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

32

Table 5: Key item classes percentages for personal non-financial reasons of men versus women.

Personal reasons for not choosing Men — Women

Complex/Difficult 13.95% — 12.33%

Math 13.95% — 10.96%

Boring 5.43% — 1.33%

Constantly evolving 0.00% — 4.11%

No interest 6.20% — 8.22%

Other career 6.98% — 17.81%

Personal reasons for choosing Men — Women

Interesting 30.47% — 31.51%

Great impact 5.47% — 6.85%

AI is the future 9.38% — 9.59%

lidity that were identified in software engineering re-

search (Ralph, 2021). Due to the guidelines consid-

ered, we have identified and analyzed three aspects:

construct validity, internal validity, and external va-

lidity. For internal validity, we focus specifically on

the participant set, participant selection, dropout con-

tingency measures, and author biases.

Construct Validity. To reduce the authors’ biases,

the questions were developed in a multi-step process

as outlined in the Survey Design. The suggested sur-

vey questions aligned with the research objectives as

stated in the Introduction.

Internal Validity. The potential internal threats iden-

tified by us were participant and participant selection,

drop-out rates, author subjectivity, and ethics.

Participant Set and Participant Selection. Ev-

ery student enrolled in the AI course, regardless

of gender or other characteristics, has been noti-

fied about the survey and asked to participate in it.

Consequently, the target group of participants was

comprehensive, eliminating any potential risks as-

sociated with the set of participants or their selec-

tion.

Drop-Outs Rates. Due to the voluntary nature

of the survey, we had limited methods to reduce

the dropout rates. The survey consisted of only a

few questions in order to increase student partici-

pation. The open-ended questions were optional.

By outlining the benefits of our research and al-

lowing the survey to remain open for two weeks,

we encouraged participation.

Author Subjectivity. Aware of the possible sub-

jectivity in data processing, we have taken this

into account and examined it. We tried to re-

duce this risk by using text analysis according

to the recommended data processing protocols.

Additionally, by taking into account suggested

data processing practices, we have validated each

other’s work. By debating every facet (includ-

ing the clarity of the approach, the selection of

keywords, and the themes), we attempted a non-

subjective approach.

Ethics in our Research. We demonstrated our

commitment to ethics by providing participants

with information about our purpose of collecting

data, our anonymous data collection method, and

our intended use of the data. Additionally, we

made it clear that participation was voluntary, and

some of them chose not to do so as evidence (from

230 students, only 198 participated).

External Validity. We examine the potential to gen-

eralize the findings of our study. One concern is

whether the results can be extrapolated to a broader

cohort of AI (or even IT) students. We mention that

any extrapolation can not be made to the whole so-

ciety since we considered a specific cohort. How-

ever, we can extrapolate to the students’ set enrolled

in IT, with some caution, because the percentage of

women who participated in the study is comparable

to the percentage of women enrolled in general in

Computer Science studies in universities. Also, the

men/women percentages in our study correlate with

the global gender percentages in STEM according to

the Global Gender Gap Report (2023) (Zahidi, 2023).

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

This research aims to evaluate students’ attitudes and

interest in AI advancement and ethics with respect to

gender identity. The survey design was iterative, with

changes made to ensure accuracy. The data were col-

lected in English to minimize translation threats and

ensure accurate analysis.

The study involved 230 second-year computer sci-

ence students, of which 198 participated. The study’s

female representation was statistically significant, as

it correlates with the gender percentages of women

enrolled in computer science in universities. The

Student Views in AI Ethics and Social Impact

33

methodology used was thematic analysis, with key

items divided into classes based on frequency.

The responses to the survey revealed that AI will

significantly impact daily life, particularly in areas

such as medicine, education, and photo/video pro-

cessing. While there are no significant differences

between men and women in their perceptions of the

most affected domains, men are more aware of poten-

tial changes in Computer Science, autonomous driv-

ing, image and video processing, and chatbot usage.

Women, however, mention more the impact of losing

human abilities.

Both men and women perceive potential threats in

the same manner, with men more aware of war, AI

controlled drones, terrain recognition, and informa-

tional war. They also seem to be more aware of fake

news and disinformation.

Ethical reasons were more prominent among

women, with women expressing a desire to help peo-

ple in various aspects of life, such as saving people

from rare diseases and making society more comfort-

able. Men were more preoccupied with financial as-

pects, while women were more concerned with help-

ing others.

The study aimed to minimize potential risks and

validate the findings through construct validity, inter-

nal validity, and external validity.

The study revealed that both men and women had

distinct motivations and priorities when it came to

emerging technologies. While men focused more

on financial gains and advancements, women had

a stronger inclination towards ethical considerations

and helping others. Overall, the research shed light on

the gender differences in motivations and highlighted

the need for a balanced approach in the development

and implementation of emerging technologies.

In the future, we hope to expand the study to in-

clude a larger and more diverse cohort of students

from other universities, resulting in a widely compa-

rable data set across European or international institu-

tions. Analyzing the data not only in terms of gender

but also comparing differences among different na-

tionalities as well as the development over time for

several generations of students would be great next

steps, and the paper at hand is the first step in that

direction.

REFERENCES

Abdullah, S. M. (2019). Artificial intelligence (ai) and its

associated ethical issues. ICR Journal, 10:124–126.

AI bots have achieved the capability to interact with

humans and build relationships through conversations.

Baeza-Yates, R. (2022). Ethical challenges in ai. Proceed-

ings of the Fifteenth ACM International Conference

on Web Search and Data Mining, pages 1–2.

Banciu, D. and C

ˆ

ırnu, C. E. (2022). Ai ethics and data pri-

vacy compliance. In 2022 14th International Confer-

ence on Electronics, Computers and Artificial Intelli-

gence (ECAI), pages 1–5. IEEE.

Borenstein, J. and Howard, A. (2021). Emerging challenges

in ai and the need for ai ethics education. AI and

Ethics, 1:61–65.

Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., and Terry, G. (2019).

Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sci-

ences, chapter Thematic Analysis, pages 843–860.

Brown, J., Park, T., Chang, J., Andrus, M., Xiang, A., and

Custis, C. (2022). Attrition of workers with minori-

tized identities on ai teams. In Equity and Access in

Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization, pages 1–

9.

Callas, V. . (1992). Predicting ethical values and training

needs in ethics. Journal of Business ethics, 11:761–

769.

Cave, S., Dihal, K., Drage, E., and McInerney, K. (2023).

Who makes ai? gender and portrayals of ai scientists

in popular film, 1920–2020. Public Understanding of

Science, 32:745–760.

Cernadas, E. and Calvo-Iglesias, E. (2020). Gender per-

spective in artificial intelligence (ai). ACM Interna-

tional Conference Proceeding Series, pages 173–176.

Fisher, E. J. P. and Fisher, E. (2023). A fresh look at ethical

perspectives on artificial intelligence applications and

their potential impacts at work and on people. Busi-

ness and Economic Research, 13(3):1–22.

Gallivan, M., Adya, M., Ahuja, M., Hoonakker, P., and

Woszczynski, A. (2006). Workforce diversity in the

it profession: Recognizing and resolving the shortage

of women and minority employees panel: Workforce

diversity in the it profession: Recognizing and resolv-

ing the shortage of women and minority employees.

pages 44–45.

Green, B. P. (2018). Ethical reflections on artificial intelli-

gence.

Jakesch, M., Buc¸inca, Z., Amershi, S., and Olteanu, A.

(2022). How different groups prioritize ethical val-

ues for responsible ai. pages 310–323. Association

for Computing Machinery.

Kennedy, J. A., Kray, L. J., and Kray, J. (2013). Who is

willing to sacrifice ethical values for money and so-

cial status?: Gender differences in reactions to ethical

compromises. Social Psychological and Personality

Science, 5.

Kennedy, J. A., Kray, L. J., and Kray, J. (2014). Gender

and reactions to ethical compromises 2 who is willing

to sacrifice ethical values for money and social sta-

tus? gender differences in reactions to ethical compro-

mises. Social Psychological and Personality Science,

5:52–59.

Kiger, M. E. and Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis

of qualitative data: Amee guide no. 131. Medical

Teacher, 42(8):846–854.

CSEDU 2025 - 17th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

34

Mohla, S., Bagh, B., and Guha, A. (2021). A material lens

to investigate the gendered impact of the ai industry.

Motogna., S., Suciu., D., and Molnar., A. (2021). Inves-

tigating student insight in software engineering team

projects. In Proceedings of the 16th International

Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to

Software Engineering - ENASE,, pages 362–371.

Ouchchy, L., Coin, A., and Dubljevi

´

c, V. (2020). Ai in

the headlines: the portrayal of the ethical issues of

artificial intelligence in the media. AI & SOCIETY,

35:927–936.

Petrescu, M. and Motogna, S. (2023). A perspective from

large vs small companies adoption of agile method-

ologies. pages 265–272.

Petrescu, M.-A., Pop, E.-L., and Mihoc, T.-D. (2023). Stu-

dents’ interest in knowledge acquisition in artificial

intelligence. Procedia Computer Science, 225:1028–

1036.

Pop, I.-D. (2024). Prediction in pre-university education

system using machine learning methods. In ICAART

(3), pages 430–437.

Pop, I.-D. and Coroiu, A. M. (2024). Advancing educa-

tional analytics using machine learning in romanian

middle school data. In CSEDU (2), pages 230–237.

Ralph, P. (2021). Acm sigsoft empirical standards for

software engineering research, version 0.2. 0. URL:

https://github. com/acmsigsoft/EmpiricalStandards.

Rogers, C. R. (1966). Client-centered psychotherapy”, vol-

ume 3.

Roopaei, M., Horst, J., Klaas, E., Foster, G., Salmon-

Stephens, T. J., and Grunow, J. (2021). Women in

ai: Barriers and solutions. pages 0497–0503. IEEE.

Rothenberger, L., Fabian, B., and Arunov, E. (2019). Rele-

vance of ethical guidelines for artificial intelligence-a

survey and evaluation. Progress Papers.

Runeson, P. and H

¨

ost, M. (2009). Guidelines for conduct-

ing and reporting case study research in software en-

gineering. Empirical Soft. Eng., 14(2):131–164.

Schminke, M. and Ambrose, M. L. (1997). Asymmetric

perceptions of ethical frameworks of men and women

in business and nonbusiness settings. Journal of Busi-

ness Ethics, 16:719–729.

Vieweg, S. H. (2021). AI for the Good. Springer.

Yarger, L., Payton, F. C., and Neupane, B. (2020). Algo-

rithmic equity in the hiring of underrepresented it job

candidates. Online Information Review, 44:383–395.

Zahidi, S. (2023). Global gender gap report 2023.

Zhou, J., Savage, S., Chen, F., Berry, A., Reed, M., and

Zhang, S. (2020). A survey on ethical principles of ai

and implementations. pages 3010–3017. IEEE.

Student Views in AI Ethics and Social Impact

35