Traumatic Rescue Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in

Firefighters: The Moderating Roles of Inhibitory Control and

Cognitive Flexibility

Zhong Xia and Wang Jingyi

Shanghai Fire Research Institute of MEM, Shanghai, China

Keywords: Firefighters, PTSD, Traumatic Stress Exposure, Inhibitory Control, Cognitive Flexibility.

Abstract: OBJECTIVES: This study aimed to analyze the correlation between traumatic stress exposure and PTSD

symptoms in Chinese firefighters using questionnaire and test methods, and to examine the moderating

effects of inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility of executive functions.

METHODS: A total of 263 frontline firefighters from China participated in this study. The self-developed

"20-item Firefighter Stress Trauma Exposure Experience Inventory" was employed to investigate the

subjects' experiences of traumatic events related to firefighting and rescue tasks since their recruitment. The

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale (PCL-5) was used to assess the presence and severity of PTSD-related

symptoms. Inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility were evaluated using the Stroop test and the number

manipulation test, respectively. A moderating model was constructed through path analysis.

RESULTS: Linear regression analysis revealed that traumatic stress exposure significantly and positively

predicted the severity of PTSD symptoms in firefighters (p < 0.05). The moderating effect of inhibitory

control was significant (p < 0.05), with simple slope analysis indicating that firefighters with strong

inhibitory control were less adversely affected by traumatic stress exposure. Although the moderating effect

of cognitive flexibility was not significant (p > 0.05), the simple slope analysis exhibited a trend similar to

that of inhibitory control.

CONCLUSION: Inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility can moderate the development of PTSD in

firefighters to some extent. The findings underscore the potential value of utilizing executive function and

other cognitive training to enhance firefighters’ resilience to PTSD.

1 INTRODUCTION

As an unique occupational group, firefighters are

entrusted with the critical tasks of fire prevention,

fire suppression, and emergency rescue, all of which

entail significant danger, complexity, and

uncertainty. Firefighters are frequently exposed to

various hazards, intense auditory and visual stimuli,

traumatic scenes, and the experience or witnessing of

casualties among themselves and others during

rescue missions. Such exposures can easily lead to

traumatic experiences and, consequently, to various

psychological disorders (Smith, Goldstein, & Grant,

2016). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is

characterized by the delayed onset and persistence of

intense fear, anxiety, helplessness, distress, and other

mental disorders resulting from exceptionally

threatening or catastrophic psychological trauma

(Goldstein et al., 2016). PTSD is one of the most

common mental disorders among firefighters,

significantly impairing their occupational health.

Numerous studies have investigated the prevalence of

PTSD in firefighters, with lifetime prevalence rates

ranging from 1.9% to 57% across different countries,

depending on sample sources and assessment methods

(Obuobi-Donkor, Oluwasina, Nkire, & Agyapong,

2022). Overall, firefighters have a higher risk of

developing PTSD and experience more severe

symptoms than the general population.

Various traumatic task experiences are often

considered the primary triggers of PTSD in

firefighters (Serrano-Ibanez, Corras, Del Prado, Diz,

& Varela, 2022). Due to the nature of their work,

firefighters are more frequently exposed to traumatic

events than the general population, including

witnessing gruesome and bloody scenes,

experiencing or witnessing severe injuries, facing

death directly, and encountering various shocking

disaster scenarios (Wagner et al., 2021). In addition

to task experiences, numerous studies have identified

other variables that influence the development of

Xia, Z. and Jingyi, W.

Traumatic Rescue Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Firefighters: The Moderating Roles of Inhibitory Control and Cognitive Flexibility.

DOI: 10.5220/0013036700003938

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2025), pages 155-164

ISBN: 978-989-758-743-6; ISSN: 2184-4984

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

155

PTSD, such as age (Chung, Lee, Jung, & Nam,

2015), marital status (Chen et al., 2007), level of

burnout (Meyer et al., 2012), work climate (Jo et al.,

2018), social support (Jin et al., 2022; Shi, Chen, Li,

& An, 2021), history of psychological and

psychiatric disorders (Kim, Park, & Kim, 2018;

Noor, Pao, Dragomir-Davis, Tran, & Arbona, 2019),

and cognitive factors (Wild & Gur, 2008). The

development of PTSD is thus a multifactorial

process, with traumatic experiences being one of the

most critical causal factors.

Typical symptoms of PTSD include recurrent

intrusive traumatic experiences (such as flashbacks

and nightmares), persistent avoidance, negative

alterations in cognition and mood, and heightened

arousal (Pietrzak et al., 2015). These symptoms

make it difficult for firefighters with PTSD to fully

engage in rescue missions, potentially leading to

mission hindrance or failure. PTSD has also been

associated with cognitive impairments (Qureshi et

al., 2011; Schuitevoerder et al., 2013). Patients with

PTSD often exhibit varying degrees of cognitive

deficits, such as impairments in memory and

learning (Johnsen & Asbjornsen, 2008; Mattson,

Nelson, Sponheim, & Disner, 2019), visuospatial

processing (Kunimatsu, Yasaka, Akai, Kunimatsu, &

Abe, 2020), and central executive functions

(Jagger-Rickels et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019; Polak,

Witteveen, Reitsma, & Olff, 2012), such as

inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility.

Inhibitory control refers to the mental process by

which individuals regulate their attention, thoughts,

behaviors, or emotions to overcome strong internal

tendencies or external temptations, while cognitive

flexibility refers to the ability to shift cognitive

resources across multiple tasks (Diamond, 2012).

Studies have shown that these executive functions

are related to PTSD symptoms such as flashbacks,

nightmares, persistent anxiety, depression, and

heightened arousal (Fitzgerald, DiGangi, & Phan,

2018). Some researchers even suggest that deficits in

executive functions, particularly inhibitory control,

make it difficult for PTSD patients to suppress

memories and thoughts related to traumatic

experiences, leading to recurrent intrusive memories

and persistent negative emotions (Cavicchioli et al.,

2020; Philippot & Agrigoroaei, 2017).

Therefore, researchers have explored the

application of systematic cognitive training in the

treatment and rehabilitation of PTSD, achieving

positive results with interventions such as Eye

Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing

(EMDR) (Jeffries & Davis, 2013) and Cognitive

Processing Therapy (CPT) (Asmundson et al., 2019;

Resick, Suvak, Johnides, Mitchell, & Iverson, 2012).

Based on these findings, it is reasonable to

hypothesize that the chain of PTSD triggered by

traumatic events is moderated by individual

cognitive abilities, such as executive functions.

In this study, frontline firefighters from eastern

and central China were selected to investigate the

pathways by which traumatic task experiences affect

PTSD symptoms and to examine the moderating

effect of higher cognitive abilities, particularly

central executive functions, on this relationship.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Research Design

This retrospective study involved frontline

firefighters (defined as those serving in basic fire

rescue stations) from Anhui and Shanghai province,

China. We assessed their exposure to traumatic

events related to firefighting and rescue duties since

their recruitment and evaluated their current PTSD

symptoms using questionnaires. Additionally, we

measured the participants' inhibitory control and

cognitive flexibility using a set of executive function

tests administered on handheld PDA devices. All

assessments were conducted at the fire rescue

stations where the subjects were employed, with

participants gathered in a conference room to

complete the tests and questionnaires. Informed

consent was obtained from all station officers

(station chiefs or instructors) prior to the study.

The specific procedures for administering the

tests were as follows: First, permission was obtained

from the chief officers of each fire station to conduct

the study. Before administering the tests, these

officers collected demographic information on all

station members, including gender, age, length of

service, marital status, and educational background.

The fire station officers then organized the subjects

to take the tests in the conference room, ensuring

they were seated at intervals to avoid interruptions.

Once all subjects were ready, the researcher guided

them through the completion of the questionnaires

and tests.

2.2 Tools

2.2.1 Traumatic Rescue Experiences

The "20-item Firefighters ’ Stress Trauma

Exposure Experience Inventory," a self-compiled

tool, was used to investigate subjects' exposure to

traumatic events related to firefighting and rescue

missions since their recruitment. The questionnaire

includes 20 items representing typical stress trauma

experiences, such as life-threatening situations for

oneself and comrades, witnessing brutal scenes,

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

156

handling dead bodies or severely injured individuals,

and being present at disaster scenes. Each item is

scored on a 3-point scale: 0 (never), 1 (once), and 2

(twice or more). Higher scores indicate more

extensive exposure to stress trauma. The Cronbach's

alpha coefficient of the scale was 0.914, indicating

good reliability. Specific inventory items are

presented in Appendix.

2.2.2 PTSD Symptoms

The Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Scale (PCL-5)

was used to assess the presence and severity of

PTSD-related symptoms. The scale consists of 20

items that meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD

according to the American Psychiatric Association’

s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (Blevins,

Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015). Although

the PCL-5 is not a stand-alone diagnostic tool for

PTSD, it can be used for initial assessment and

monitoring of potential PTSD-related symptoms

(Wortmann et al., 2016). The Cronbach's alpha

coefficient of the scale was above 0.9, indicating

good reliability (Cheng et al., 2020). Specific

inventory items are presented in Appendix.

2.2.3 Inhibitory Control and Cognitive

Flexibility

A classic Stroop test was used to assess subjects’

inhibitory control, where color words were presented

randomly, and the task was to respond to the font

color of the word with a keystroke. The test included

two conditions: congruent (the word meaning matches

the font color, e.g., "red" in red) and incongruent (the

word meaning does not match the font color, e.g.,

"yellow" in red). The test comprised 36 trials, with

half in the congruent condition and half in the

incongruent condition. Higher accuracy and shorter

response times indicate better inhibitory control.

A number manipulation test was designed to

assess cognitive flexibility. In this test, a pair of

numbers (both within 10) was presented randomly,

and the task was to quickly determine the size

relationship between the two numbers. If the left

number was greater, subtraction was performed (left

minus right); if the right number was greater,

addition was performed. Results were entered via a

numeric keyboard. The test consisted of 20 trials,

requiring 10 conversion processes (switching from

subtraction to addition or vice versa). All subjects

completed a general numerical ability test before this

test to control for differences in mathematical ability.

Higher accuracy and shorter completion times

indicated better cognitive flexibility, assuming

consistent general numerical ability among subjects.

2.3 Subjects

The study involved administering scales and tests in

20 fire rescue stations (the most basic firefighting

units) in Anhui and Shanghai province, China. All

subjects met the following criteria: (1) informed

consent and voluntary participation; (2) completion

of all induction training and formal enrollment in

service; (3) participation in at least one rescue

mission. Subjects were excluded if they: (1) were

absent or left midway through the test due to

vacation, duty, or rescue tasks; (2) had a history of

mental illness or a family history of hereditary

mental illness; (3) had never participated in a fire

rescue mission since recruitment; (4) did not wish to

participate for other reasons.

2.4 Data Analysis

All scale and test data were analyzed using IBM

SPSS 22.0 and IBM SPSS AMOS 22.0.

Demographic data were described using frequency,

percentage, mean, and standard deviation. Linear

regression was employed to model the pathway

linking traumatic rescue experiences to PTSD

symptom severity. Pathway analysis was conducted

to examine the moderating effects of inhibitory

control and cognitive flexibility on this relationship.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Sociodemographic Characteristics

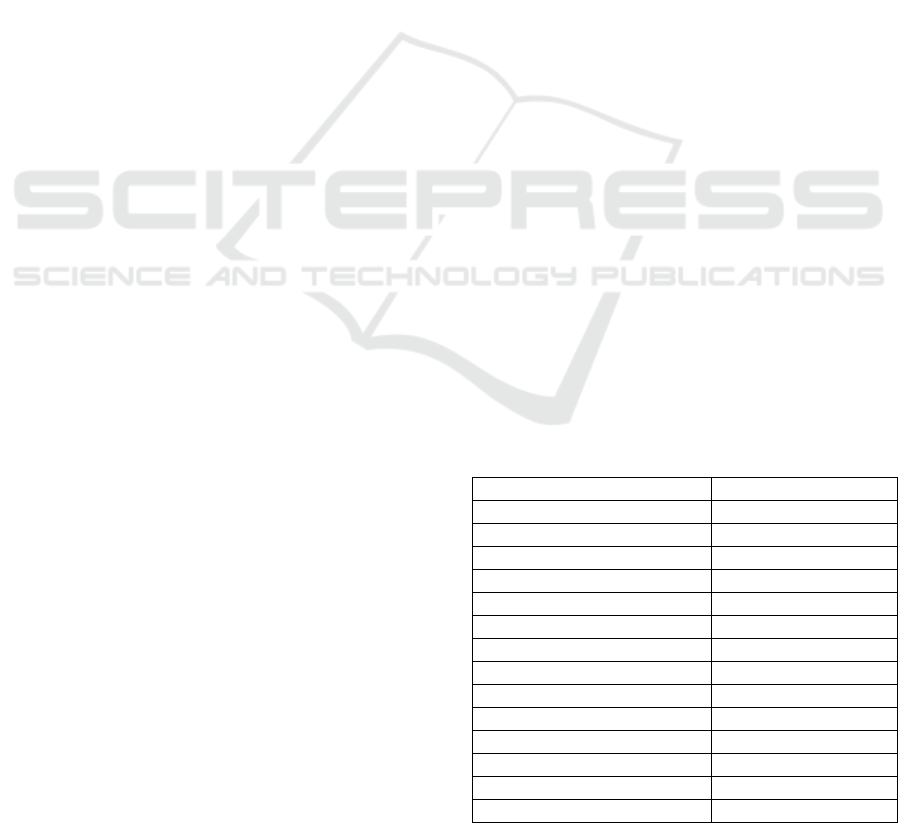

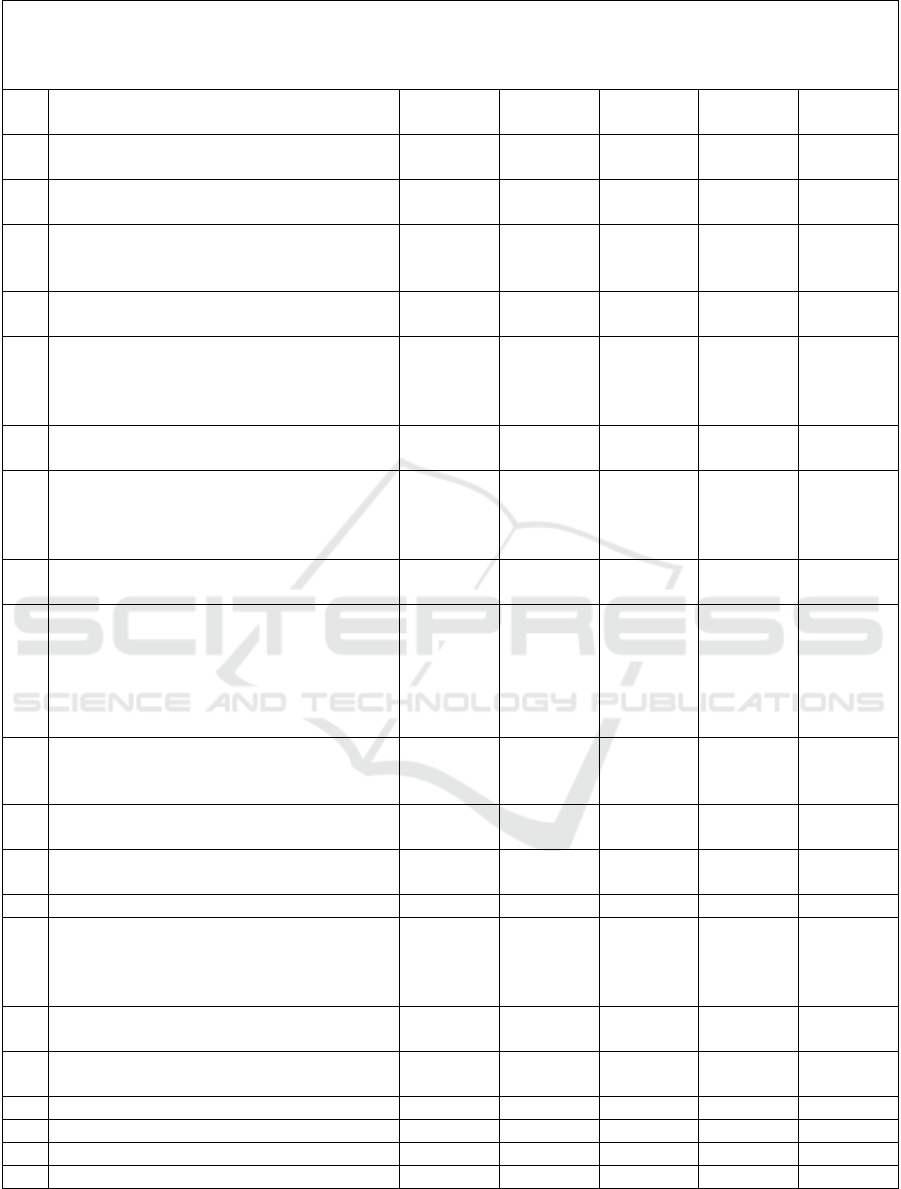

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic information

of all subjects. Data from 263 valid subjects were

collected, all male. Ages ranged from 20 to 44 years,

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics(n=263).

items frequency(%)

age

≤25 123(46.8)

26~30 104 (39.5)

>30 36 (13.7)

Enlistment duration

≤3 142 (54)

4~8 76 (28.8)

>8 45 (17.2)

Marital status

married 72 (27.4)

unmarried 191 (72.6)

Educational background

Below university degree 210 (79.9)

University degree or above 53 (20.1)

Traumatic Rescue Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Firefighters: The Moderating Roles of Inhibitory Control and

Cognitive Flexibility

157

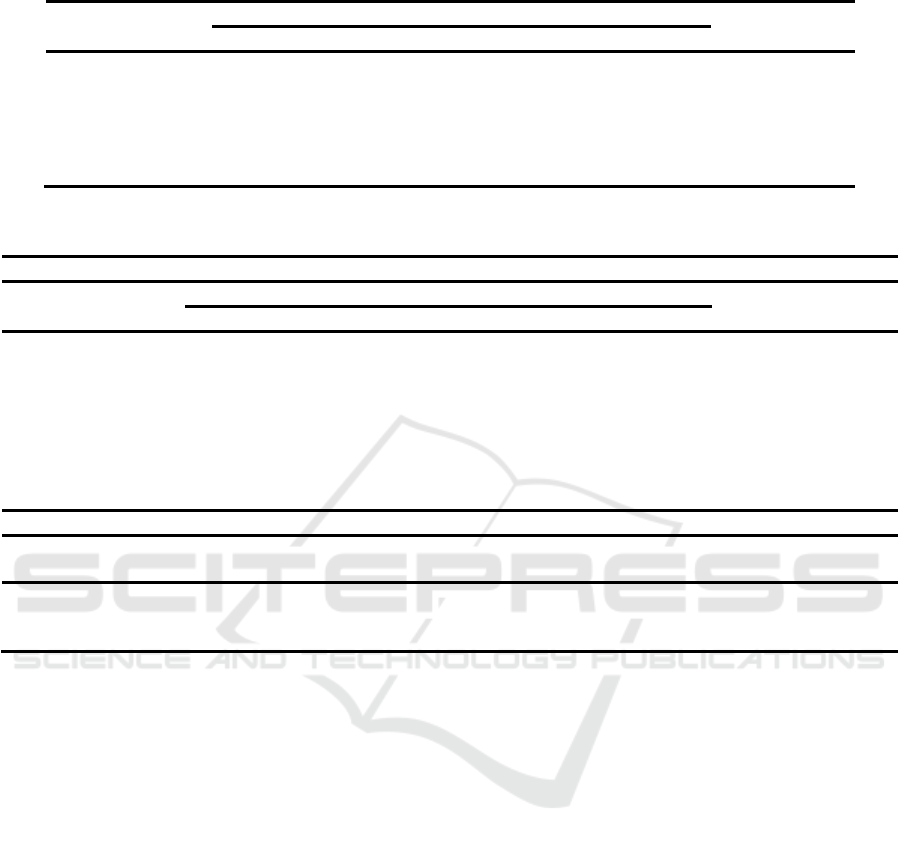

Table 2: Linear regression model of PTSD symptoms on TRAUMA scores.

Unstandardized coefficients Standardized coefficients

t P value

B Standard error Beta

Constant 7.095 1.032 - 6.872 0.000**

TRAUMA scores 0.260 0.071 0.221 3.655 0.000**

R

2

0.049

Adjusted R

2

0.045

F F (1, 261) =13.356, p=0.000

D-W 1.710

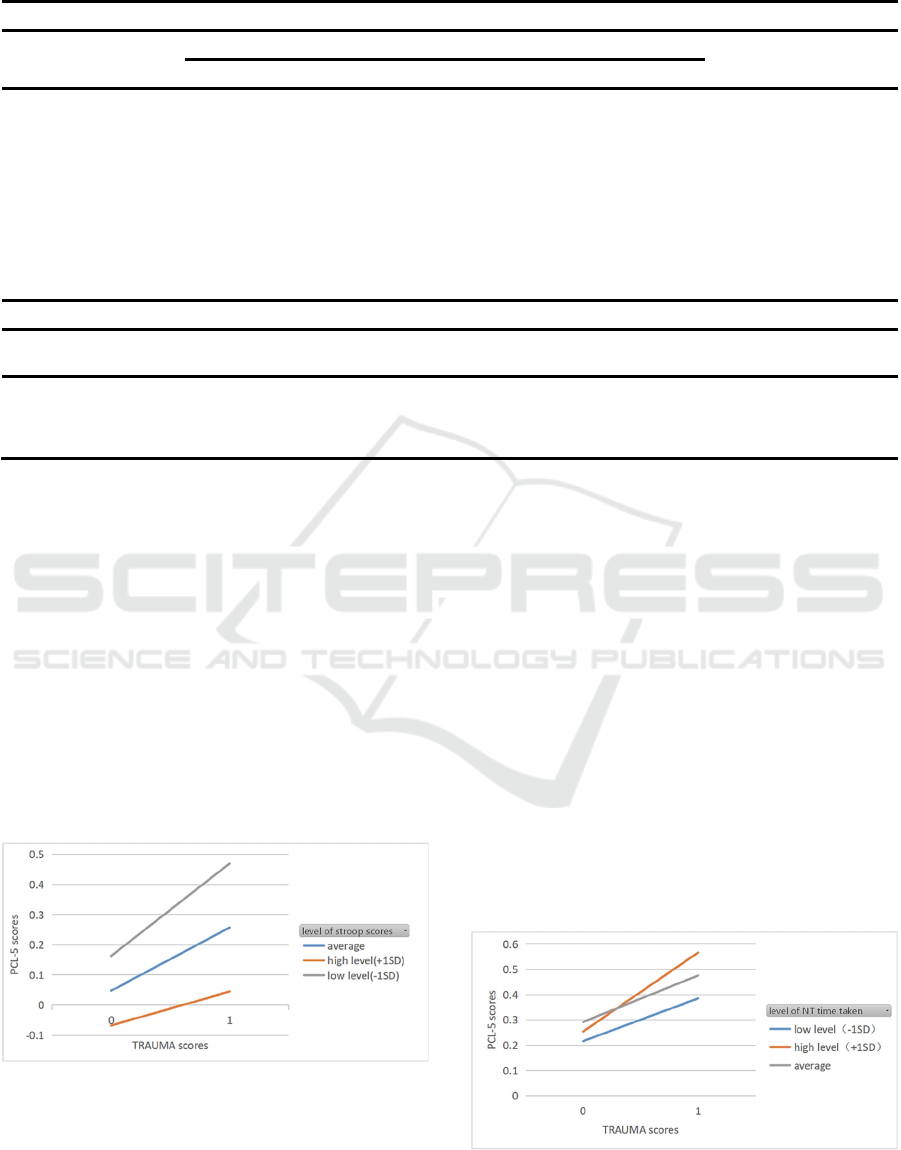

Table 3: Mediating model of Stroop test scores.

Model summary

Unstandardized coefficients Standardized coefficients

t P value

B Standard error Beta

constant 0.048 0.059 - 0.802 0.423

TRAUMA scores 0.209 0.060 0.209 3.494 0.001**

Stroop scores -0.115 0.060 -0.115 -1.929 0.055

TRAUMA*Stroop -0.097 0.042 -0.140 -2.341 0.020*

R

2

0.084

R

2

changes 0.019

F value F (3,259)=7.882,p=0.000

F value changes F(1,259)=5.482,p=0.020

simple slope analysis

Levels of moderating variable

Regression

coefficients

Standard error t P value 95% CI

average 0.209 0.060 3.494 0.001 [0.092,0.327]

High level(+1SD) 0.112 0.076 1.465 0.144 [-0.038,0.262]

Low level(-1SD) 0.307 0.069 4.435 0.000 [0.171,0.442]

with a mean age of 26.51 ± 4.18 years (M ± SD).

The shortest length of service was less than 1 year,

and the longest was 25 years, with a mean of 4.44 ±

4.29 years (M ± SD). There were 191 unmarried

subjects (72.6%) and 72 married subjects (27.4%).

Educational levels were as follows: 1 junior high

school graduate (0.4%), 86 high school graduates

(32.7%), 123 college degree holders (46.8%), 48

university degree holders (18.3%), and 5 with a

bachelor’s degree or higher (1.9%).

3.2 The Effect of Traumatic Rescue

Experiences on PTSD Symptoms

A linear regression model was constructed with the

subjects' scores on the PCL-5 as the dependent

variable and their scores on the '20-item Firefighters’

Stress Trauma Exposure Experience Inventory'

(hereafter referred to as the TRAUMA Inventory) as

the independent variable. Table 2 presents the model

fit with R

2

=0.049, indicating that this independent

variable explains 4.9% of the variance in the

dependent variable. The model passed the F-test

(F=13.356, p=0.000<0.05). The regression

coefficient for the independent variable was 0.260

(p=0.000<0.05), indicating that the independent

variable had a significant positive effect on the

dependent variable. This result suggests that

firefighters who scored high on the TRAUMA

Inventory may exhibit a higher propensity for PTSD

symptoms.

3.3 Moderating Effects of Inhibitory

Control and Cognitive Flexibility

To explore the moderating effects of subjects'

inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility on PTSD

symptoms, all variables involved in the analysis

were converted to standard Z scores. The subjects'

scores on the Stroop test and the number

manipulation test (hereafter referred to as the NT)

were added to the model constructed in section 3.2.

Table 3 presents the model with Stroop test scores as

a moderating variable. In this model, the number of

correct responses (ranging from 0 to 36) was used as

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

158

Table 4: Mediating model of NT time taken.

Model summary

Unstandardized coefficients Standardized coefficients

t P value

B Standard error Beta

constant 0.254 0.418 - 0.608 0.544

TRAUMA scores 0.222 0.061 0.222 3.626 0.000**

NT time taken 0.038 0.065 0.038 0.581 0.562

TRAUMA*NT 0.053 0.067 0.048 0.793 0.429

R

2

0.057

R

2

changes 0.002

F value F (3, 257) = 3.110, p=0.010

F value changes F (1,257) = 0.628,p=0.429

simple slope analysis

Levels of moderating variable

Regression

coefficients

Standard error t P value 95% CI

average 0.222 0.061 3.626 0.000 [0.102,0.342]

High level(+1SD) 0.275 0.093 2.941 0.004 [0.092,0.458]

Low level(-1SD) 0.169 0.087 1.931 0.055 [-0.002,0.340]

an indicator of test performance. The interaction

regression coefficient for TRAUMA scores and

Stroop scores was −0.097(p=0.020<0.05), indicating

a significant moderating effect. Further simple slope

analysis showed that when the moderating variable

(Stroop scores) was at a low or average level, there

was a significant positive effect of TRAUMA scores

on PTSD symptoms (B=0.307,p=0.000<0.05;

B=0.209,p=0.001<0.05), while at a high level, this

effect was not significant (B=0.112,p=0.144>0.05),

as shown in Figure 1 and Table 3. This suggests that

subjects with greater inhibitory control are somewhat

able to withstand the impact of traumatic rescue

experiences, as evidenced by the lesser effect on

PTSD symptoms.

Figure 1: Simple slope diagram for different Stroop scores

levels.

Table 4 presents the model with NT scores as a

moderating variable. Due to the low difficulty of the

test items (addition and subtraction within 10), the

vast majority of subjects achieved nearly 100%

accuracy. Therefore, the time taken by subjects to

complete the test was used as an indicator of

performance, with longer times indicating worse

cognitive flexibility. To avoid confounding general

numerical ability with cognitive flexibility, subjects'

time on the General Numerical Ability Test

(completed before the formal test) was added as a

covariate. The model fit indicated that the interaction

term's regression coefficient was

0.053(p=0.429>0.05), suggesting that the

moderating effect of NT was not significant. Despite

the poor model fit, simple slope analysis was

performed, as shown in Figure 2. Results indicated

that TRAUMA scores had a significant positive

effect on PTSD symptoms when NT time was at

average or high levels (B=0.222, p=0.000 < 0.05;

B=0.275, p=0.004 < 0.05), but not at low levels

(B=0.169, p=0.055 > 0.05).

Figure 2: Simple slope diagram for different NT levels.

Traumatic Rescue Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Firefighters: The Moderating Roles of Inhibitory Control and

Cognitive Flexibility

159

4 DISCUSSION

This study constructed a pathway model to examine

the effect of stress trauma exposure on the

development of PTSD symptoms in firefighters.

Findings indicate that the extent of stress trauma

exposure significantly positively affects the severity

of PTSD symptoms in firefighters, meaning those

who experience more traumatic rescue events tend to

exhibit more PTSD symptoms. Traumatic events and

scenarios are inevitable for firefighters. The majority

of firefighters face shocking events including injury,

illness, death, heat, noise, and explosions, making

them more susceptible to PTSD compared to the

general population. Studies in the United States,

Canada, and the United Kingdom show that

firefighters have a much higher prevalence of PTSD

than the general population, as well as military

personnel and first responders (Obuobi-Donkor et

al., 2022). Additionally, PTSD can coexist with

other psychological disorders, and firefighters are

often at risk for other mental health problems such as

anxiety and depression due to their work

environment (Alghamdi, Hunt, & Thomas, 2015),

complicating the screening, diagnosis, and

intervention processes for PTSD.

For PTSD prevention, avoiding stressors is an

effective option (Kyron, Rikkers, LaMontagne,

Bartlett, & Lawrence, 2022). However, for

firefighters, this is difficult to achieve since exposure

to various stressors is inherent to their job. Even

retired firefighters may have a high prevalence of

PTSD (McFarlane & Bryant, 2007). Thus,

preemptive approaches to reduce PTSD incidence in

firefighters are challenging.

In recent years, cognitive therapy has been

widely used for treating various psychological

disorders, such as autism (Wass & Porayska-Pomsta,

2014), Alzheimer's disease (Vecchio et al., 2022),

and PTSD (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Executive

function, a core aspect of higher cognitive abilities,

has been linked to PTSD development and recovery

(Olff, Polak, Witteveen, & Denys, 2014; Smits,

Geuze, Schutter, van Honk, & Gladwin, 2021). This

study tested the moderating effects of inhibitory

control and cognitive flexibility. Results indicated

that inhibitory control significantly moderates PTSD

symptoms, with stronger inhibitory control

associated with fewer PTSD symptoms. Although

the moderating effect of cognitive flexibility was not

significant, slope analysis suggested a potential

effect. Inhibitory control allows individuals to

suppress dominant responses detrimental to current

activities (Ullsperger & Danielmeier, 2022), helping

control intrusive traumatic experiences and negative

thinking in PTSD. Cognitive flexibility enables

individuals to transfer cognitive resources between

tasks, potentially reducing hypervigilance, a

common PTSD symptom, by shifting attention and

adjusting mental states.

Firefighters' occupational characteristics make

them vulnerable to various hazards and traumatic

events, and their management practices may increase

susceptibility to anxiety, depression, and stress

disorders, impacting performance and increasing

separation and suicide risks (Davidson, Stein,

Shalev, & Yehuda, 2004). Effective treatment or

alleviation of PTSD symptoms is crucial for

maintaining firefighters' occupational health.

However, many PTSD treatments are not suitable for

firefighters due to the long duration and systematic

interventions required, often necessitating time away

from duty, which is not feasible. Moreover, the fire

department's militaristic and masculine culture can

stigmatize mental health treatment, leading to

condition concealment or negative treatment. Given

these factors, enhancing firefighters' resilience to

traumatic stress through cognitive training to reduce

PTSD probability or alleviate symptoms appears to

be a prudent intervention.

5 CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study verified the moderating

effects of inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility

on PTSD morbidity and symptom severity in

firefighters. Firefighters with greater inhibitory

control and cognitive flexibility under the influence

of traumatic rescue experiences are less likely to

develop PTSD symptoms. Enhancing executive

functioning in firefighters to prevent PTSD onset or

reduce symptom severity is a viable strategy for

improving their occupational mental health.

REFERENCES

Alghamdi, M., Hunt, N., Thomas, S. (2015). The

effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy with

traumatised firefighters in Saudi Arabia: A randomized

controlled study. Behaviour Research and Therapy,

66, 64-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.brat.2015.01.008.

Asmundson, G. J. G., Thorisdottir, A. S., Roden-Foreman,

J. W., Baird, S. O., Witcraft, S. M., Stein, A. T.,

Powers, M. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of

cognitive processing therapy for adults with

posttraumatic stress disorder. Cognitive Behaviour

Therapy, 48(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/165060

73.2018.1522371.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

160

Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T.

K., Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress

disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development

and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of

Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489-498. https://doi.org/

10.1002/jts.22059.

Cavicchioli, M., Ramella, P., Vassena, G., Simone, G.,

Prudenziati, F., Sirtori, F., Maffei, C. (2020). Mindful

self-regulation of attention is a key protective factor

for emotional dysregulation and addictive behaviors

among individuals with alcohol use disorder. Addictive

Behaviors, 105, 106317. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106317.

Chen, Y. S., Chen, M. C., Chou, F. H., Sun, F. C., Chen, P.

C., Tsai, K. Y., Chao, S. S. (2007). The relationship

between quality of life and posttraumatic stress

disorder or major depression for firefighters in

Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Quality of Life Research, 16(8),

1289-1297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9248

-7.

Cheng, P., Xu, L. Z., Zheng, W. H., Ng, R. M. K., Zhang,

L., Li, L. J., Li, W. H. (2020). Psychometric property

study of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for

DSM-5 (PCL-5) in Chinese healthcare workers during

the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 277, 368-374.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.038.

Chung, I. S., Lee, M. Y., Jung, S. W., Nam, C. W. (2015).

Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory as related

factor for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms

according to job stress level in experienced

firefighters: 5-year study. Annals of Occupational and

Environmental Medicine, 27, 16. https://doi.org/

10.1186/s40557-015-0067-y.

Davidson, J. R., Stein, D. J., Shalev, A. Y., Yehuda, R.

(2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder: Acquisition,

recognition, course, and treatment. The Journal of

Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 16(2),

135-147. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.16.2.135.

Diamond, A. (2012). Activities and programs that improve

children's executive functions. Current Directions in

Psychological Science, 21(5), 335-341.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412453722.

Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of

posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and

Therapy, 38(4), 319-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/

s0005-7967(99)00123-0.

Fitzgerald, J. M., DiGangi, J. A., Phan, K. L. (2018).

Functional neuroanatomy of emotion and its regulation

in PTSD. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 26(3),

116-128. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000

000000185.

Goldstein, R. B., Smith, S. M., Chou, S. P., Saha, T. D.,

Jung, J., Zhang, H., Grant, B. F. (2016). The

epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder

in the United States: Results from the National

Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related

Conditions-III. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric

Epidemiology, 51(8), 1137-1148. https://doi.org/

10.1007/s00127-016-1208-5.

Jagger-Rickels, A., Stumps, A., Rothlein, D., Park, H.,

Fortenbaugh, F., Zuberer, A., Esterman, M. (2021).

Impaired executive function exacerbates neural

markers of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Psychological Medicine, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.10

17/S0033291721000842.

Jeffries, F. W., Davis, P. (2013). What is the role of eye

movements in eye movement desensitization and

reprocessing (EMDR) for post-traumatic stress

disorder (PTSD)? A review. Behavioural and

Cognitive Psychotherapy, 41(3), 290-300.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465812000793.

Jin, F., Ashraf, A. A., Ul Din, S. M., Farooq, U., Zheng,

K., Shaukat, G. (2022). Organisational caring ethical

climate and its relationship with workplace bullying

and post-traumatic stress disorder: The role of type

A/B behavioural patterns. Frontiers in Psychology, 13,

1042297. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.10

42297.

Jo, I., Lee, S., Sung, G., Kim, M., Lee, S., Park, J., Lee, K.

(2018). Relationship between burnout and PTSD

symptoms in firefighters: The moderating effects of a

sense of calling to firefighting. International Archives

of Occupational and Environmental Health, 91(1),

117-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-017-1263-6.

Johnsen, G. E., Asbjornsen, A. E. (2008). Consistent

impaired verbal memory in PTSD: A meta-analysis.

Journal of Affective Disorders, 111(1), 74-82.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.007.

Kim, J. I., Park, H., Kim, J. H. (2018). Alcohol use

disorders and insomnia mediate the association

between PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation in

Korean firefighters. Depression and Anxiety, 35(11),

1095-1103. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22803.

Kunimatsu, A., Yasaka, K., Akai, H., Kunimatsu, N., Abe,

O. (2020). MRI findings in posttraumatic stress

disorder. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging,

52(2), 380-396. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26929.

Kyron, M. J., Rikkers, W., LaMontagne, A., Bartlett, J.,

Lawrence, D. (2022). Work-related and nonwork

stressors, PTSD, and psychological distress:

Prevalence and attributable burden among Australian

police and emergency services employees.

Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice,

and Policy, 14(7), 1124-1133. https://doi.org/10.10

37/tra0000536.

Li, G., Wang, L., Cao, C., Fang, R., Cao, X., Chen, C.,

Hall, B. J. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder and

executive dysfunction among children and

adolescents: A latent profile analysis. International

Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 19(3),

228-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2019.07.001.

Mattson, E. K., Nelson, N. W., Sponheim, S. R., Disner, S.

G. (2019). The impact of PTSD and mTBI on the

Traumatic Rescue Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Firefighters: The Moderating Roles of Inhibitory Control and

Cognitive Flexibility

161

relationship between subjective and objective

cognitive deficits in combat-exposed veterans.

Neuropsychology, 33(7), 913-921. https://doi.org/

10.1037/neu0000560.

McFarlane, A. C., Bryant, R. A. (2007). Post-traumatic

stress disorder in occupational settings: Anticipating

and managing the risk. Occupational Medicine, 57(6),

404-410. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm070.

Meyer, E. C., Zimering, R., Daly, E., Knight, J., Kamholz,

B. W., Gulliver, S. B. (2012). Predictors of

posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological

symptoms in trauma-exposed firefighters.

Psychological Services, 9(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/

10.1037/a0026414.

Noor, N., Pao, C., Dragomir-Davis, M., Tran, J., Arbona,

C. (2019). PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation in

US female firefighters. Occupational Medicine,

69(8-9), 577-585. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/

kqz057.

Obuobi-Donkor, G., Oluwasina, F., Nkire, N., Agyapong,

V. I. O. (2022). A scoping review on the prevalence

and determinants of post-traumatic stress disorder

among military personnel and firefighters:

Implications for public policy and practice.

International Journal of Environmental Research and

Public Health, 19(3), 1565. https://doi.org/10.3390/

ijerph19031565.

Olff, M., Polak, A. R., Witteveen, A. B., Denys, D. (2014).

Executive function in posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) and the influence of comorbid depression.

Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 112, 114-121.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2014.01.003.

Philippot, P., Agrigoroaei, S. (2017). Repetitive thinking,

executive functioning, and depressive mood in the

elderly. Aging & Mental Health, 21(11), 1192-1196.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1211619.

Pietrzak, R. H., Tsai, J., Armour, C., Mota, N.,

Harpaz-Rotem, I., Southwick, S. M. (2015).

Functional significance of a novel 7-factor model of

DSM-5 PTSD symptoms: Results from the National

Health and Resilience in Veterans study. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 174, 522-526. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.007.

Polak, A. R., Witteveen, A. B., Reitsma, J. B., Olff, M.

(2012). The role of executive function in posttraumatic

stress disorder: A systematic review. Journal of

Affective Disorders, 141(1), 11-21.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.001.

Qureshi, S. U., Long, M. E., Bradshaw, M. R., Pyne, J. M.,

Magruder, K. M., Kimbrell, T., Kunik, M. E. (2011).

Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of

trauma? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical

Neurosciences, 23(1), 16-28. https://doi.org/10.1176/

jnp.23.1.jnp16.

Resick, P. A., Suvak, M. K., Johnides, B. D., Mitchell, K.

S., Iverson, K. M. (2012). The impact of dissociation

on PTSD treatment with cognitive processing therapy.

Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 718-730.

https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21938.

Schuitevoerder, S., Rosen, J. W., Twamley, E. W., Ayers,

C. R., Sones, H., Lohr, J. B., Thorp, S. R. (2013). A

meta-analysis of cognitive functioning in older adults

with PTSD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(6),

550-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.0

01.

Serrano-Ibanez, E. R., Corras, T., Del Prado, M., Diz, J.,

Varela, C. (2022). Psychological variables associated

with post-traumatic stress disorder in firefighters: A

systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse,

15248380221082944. https://doi.org/10.1177/152483

80221082944.

Shi, J., Chen, Y., Li, X., An, Y. (2021). Predicting

posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms among

frontline firefighters in China. Journal of Nervous and

Mental Disease, 209(1), 23-27. https://doi.org/

10.1097/NMD.0000000000001250.

Smith, S. M., Goldstein, R. B., Grant, B. F. (2016). The

association between post-traumatic stress disorder and

lifetime DSM-5 psychiatric disorders among veterans:

Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on

Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III).

Journal of Psychiatric Research, 82, 16-22.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.06.0 22.

Smits, F. M., Geuze, E., Schutter, D., van Honk, J.,

Gladwin, T. E. (2021). Effects of tDCS during

inhibitory control training on performance and PTSD,

aggression and anxiety symptoms: A

randomized-controlled trial in a military sample.

Psychological Medicine, 52(16), 1-11. https://doi.org/

10.1017/S0033291721000817.

Ullsperger, M., Danielmeier, C. (2022). Motivational and

cognitive control: From motor inhibition to social

decision making. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral

Reviews, 136, 104600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neu

biorev.2022.104600.

Vecchio, F., Quaranta, D., Miraglia, F., Pappalettera, C.,

Di Iorio, R., L'Abbate, F., Rossini, P. M. (2022).

Neuronavigated magnetic stimulation combined with

cognitive training for Alzheimer's patients: An EEG

graph study. Geroscience, 44(1), 159-172.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-021-00508-w.

Wagner, S. L., White, N., Randall, C., Regehr, C., White,

M., Alden, L. E., Krutop, E. (2021). Mental disorders

in firefighters following large-scale disaster. Disaster

Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 15(4),

504-517. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.61.

Wass, S. V., Porayska-Pomsta, K. (2014). The uses of

cognitive training technologies in the treatment of

autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(8), 851-871.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313499827.

Wild, J., Gur, R. C. (2008). Verbal memory and treatment

response in post-traumatic stress disorder. The British

Journal of Psychiatry, 193(3), 254-255.

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045922.

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

162

Wolffe, T. A. M., Robinson, A., Clinton, A., Turrell, L.,

Stec, A. A. (2023). Mental health of UK firefighters.

Scientific Reports, 13(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.1038/

s41598-022-24834-x.

Wortmann, J. H., Jordan, A. H., Weathers, F. W., Resick,

P. A., Dondanville, K. A., Hall-Clark, B., Litz, B. T.

(2016). Psychometric analysis of the PTSD checklist-5

(PCL-5) among treatment-seeking military service

members. Psychological Assessment, 28(11),

1392-1403. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000260.

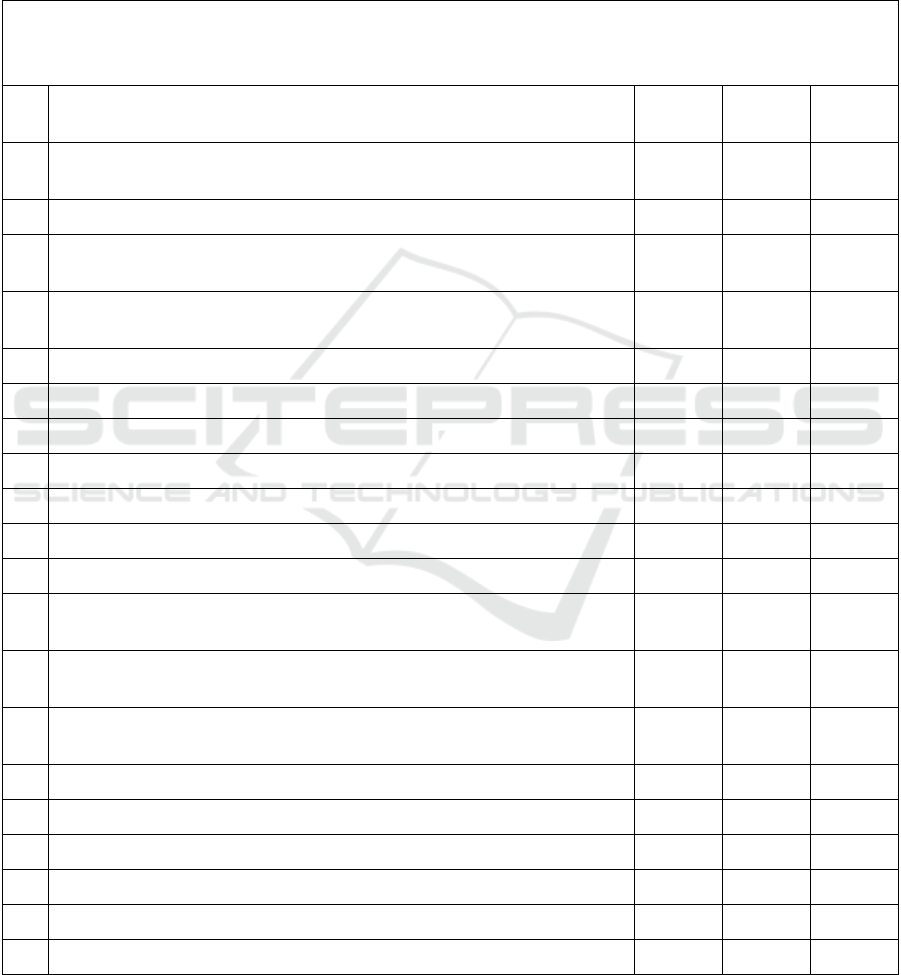

APPENDIX

the 20-item Firefighters’ Stress Trauma Exposure Experience Inventory

Instructions: Please select the number of times you have experienced the following events since your enlistment based on

your actual situation.

items 0 1 time

2 times or

more

1

Minor injuries sustained during training or missions (requiring medical

treatment but not hospitalization)

2 Seriously injured in training or missions (requiring hospitalization)

3

Witnessing a comrade slightly injured during training or mission (requiring

medical treatment but not hospitalization)

4

Witnessing a comrade seriously injured during training or mission (requiring

hospitalization for treatment)

5 Witnessing the death of a comrade in training or during a mission

6 Hearing the death of a comrade in training or during a mission

7 Participate in fire extinguishing with injuries or fatalities

8 Participate in flood, typhoon and other weather disaster rescues

9 Participate in earthquake, mudslide and other geological disaster rescues

10 Participate in traffic accident rescues

11 Rescue of suicides

12

Participate in the building (structure) and facilities and equipment collapse

accident disposals

13

Participate in the disposals of hazardous materials leaks, explosions and

poisoning

14

Participate in the disposals of pressure vessels, pipelines and other equipment

leaks and explosions

15 Rescues of burned or mutilated people

16 Rescues of seriously injured people

17 Rescues of minors

18 Witnessing the death of a minor during a mission

19 Witness/search/contact/carry bodies during the mission

20 Witness the fragmented bodies during the mission

Traumatic Rescue Experiences and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Firefighters: The Moderating Roles of Inhibitory Control and

Cognitive Flexibility

163

The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Scale (PCL-5)

Instructions: below is a list of problems that people sometimes have in response to a very stressful experience. Keeping

your worst event in mind, please read each problem carefully and then circle one of the numbers to the right to indicate

how much you have been bothered by that problem in the past month.

In the past month, how much were you

bothered by:

Not at all A little bit Moderately Quite a bit extremely

1 Repeated, disturbing, and unwanted

memories of the stressful experience?

0 1 2 3 4

2 Repeated, disturbing dreams of the stressful

experience?

0 1 2 3 4

3 Suddenly feeling or acting as if the stressful

experience were actually happening again (as

if you were actually back there reliving it)?

0 1 2 3 4

4 Feeling very upset when something reminded

you of the stressful experience?

0 1 2 3 4

5 Having strong physical reactions when

something reminded you of the stressful

experience (for example, heart pounding,

trouble breathing, sweating)?

0 1 2 3 4

6 Avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings

related to the stressful experience?

0 1 2 3 4

7 Avoiding external reminders of the stressful

experience (for example, people, places,

conversations, activities, objects, or

situations)?

0 1 2 3 4

8 Trouble remembering important parts of the

stressful experience?

0 1 2 3 4

9 Having strong negative beliefs about

yourself, other people, or the world (for

example, having thoughts such as: I am bad,

there is something seriously wrong with me,

no one can be trusted, the world is

completely dangerous)?

0 1 2 3 4

10 Blaming yourself or someone else for the

stressful experience or what happened after

it?

0 1 2 3 4

11 Having strong negative feelings such as fear,

horror, anger, guilt, or shame?

0 1 2 3 4

12 Loss of interest in activities that you used to

enjoy?

0 1 2 3 4

13 Feeling distant or cut off from other people? 0 1 2 3 4

14 Trouble experiencing positive feelings (for

example, being unable to feel happiness or

have loving feelings for people close to

you)?

0 1 2 3 4

15 Irritable behavior, angry outbursts, or acting

aggressively?

0 1 2 3 4

16 Taking too many risks or doing things that

could cause you harm?

0 1 2 3 4

17 Being “superalert” or watchful or on guard? 0 1 2 3 4

18 Feeling jumpy or easily startled? 0 1 2 3 4

19 Having difficulty concentrating? 0 1 2 3 4

20 Trouble falling or staying asleep? 0 1 2 3 4

ICT4AWE 2025 - 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

164