Effects of Different LED Light Spectra on the Shelf Life and

Nutritional Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce in a Plant

Factory

Abdullah Aldiyab and Hayriye Yildiz Dasgan

*

Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Cukurova, Adana 01330, Turkey

Keywords: Indoor Vertical Farming, Postharvest Quality, Shelf Life, Hydponic Culture, Lactuca sativa var. crispa L.,

Antioxidants.

Abstract: A study was conducted to assess the shelf life of lettuce grown under three different LED light spectra using

hydroponic techniques in a plant factory. The Batavia-type cultivar ‘Capira’ was used, and seedlings were

transferred to an ebb-and-flow system 12 days after sowing. The plant factory was maintained at 25 °C (day),

20 °C (night), with a 12-hour photoperiod, ~400 ppm CO₂, and 60–70% relative humidity. Lettuce was grown

under three LED spectra: LED1 = 70% red (610-720 nm) + 30% blue (450-495 nm), LED2 = Full PAR

spectrum (400-700 nm), LED3 = 65% red (610-720 nm) + 25% blue (450-495 nm) + 5% white (400 475 nm)

+ 5% far red (700-760).. After 30 days of growth, the lettuce was harvested and stored at 8 °C and 60–70%

humidity for 14 days. Post-storage evaluations included weight loss, chlorophyll degradation, phenolic and

flavonoid contents, nitrate levels, and mineral composition. Weight loss ranged from 1.54% to 2.80%,

chlorophyll degradation from 8.1% to 11.3%, phenolic decline from 20.2% to 23.2%, and flavonoid loss from

11.68% to 22.6%. Nitrate reduction varied from 26.0% to 47.3%. These results highlight how different LED

light spectra influence the postharvest quality and shelf life of hydroponically grown lettuce.

1 INTRODUCTION

The increasing demand for minimally processed

fruits and vegetables has drawn significant attention,

especially regarding changes in their phytochemical

properties during storage. Consumers, informed by

scientific research, are becoming more selective,

valuing not only sensory qualities like taste, aroma,

and texture but also the nutritional content, including

vitamins and minerals, when choosing fresh produce

(Özgen & Tokbaş, 2007). A substantial body of

research indicates that diets rich in fruits and

vegetables reduce the risk of chronic diseases (Block

et al., 1992). This protective effect is largely

attributed to the abundance of antioxidants and

flavonoids in these foods, which play a crucial role in

promoting health (Hertog et al., 1993). Multiple

studies have demonstrated an inverse relationship

between fruit and vegetable intake and the incidence

of certain cancers (Steinmetz & Potter, 1996; Kaur &

Kapoor, 2001). Consequently, identifying

*

Corresponding author

phytochemical profiles and evaluating antioxidant

capacities are essential steps in advancing clinical

research on specific cancer types (Özgen &

Scheerens, 2006). However, antioxidant levels in

fruits and vegetables are sensitive to various factors,

such as species differences, cultivation methods,

storage conditions, and pre-treatment processes that

affect bioactive compounds (Price et al., 1998; Del

Caro et al., 2004). This variability has generated

growing interest in assessing the antioxidant

capacities of foods consumed regularly (Sağlam,

2007). In recent years, pre-processed fruits and

vegetables have gained popularity among consumers

due to their convenience in reducing preparation time.

Maintaining high-quality standards throughout

production and storage is crucial for these products

(Martinez et al., 2008).

In this study, three types of LED lighting were

used to grow lettuce, which was harvested after 30

days of cultivation. Following harvest, the lettuce was

stored for 14 days, with chemical properties analyzed

158

Aldiyab, A. and Dasgan, H. Y.

Effects of Different LED Light Spectra on the Shelf Life and Nutritional Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce in a Plant Factory.

DOI: 10.5220/0014224200004738

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Research of Agricultural and Food Technologies (I-CRAFT 2024), pages 158-168

ISBN: 978-989-758-773-3; ISSN: 3051-7710

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

at three intervals: on the first, seventh, and fourteenth

days of storage. These analyses aimed to assess the

effects of storage duration and different lighting

conditions on the lettuce’s chemical composition. The

study provides insight into how pre-harvest

environmental conditions, such as light quality, and

post-harvest treatments influence the nutritional and

phytochemical stability of leafy greens during

storage.

The quality of freshly cut fruits and vegetables

depends on attributes such as texture, appearance,

nutritional value, and flavor (Witkowska &

Woltering, 2013). However, this quality degrades

over time due to simultaneous biological processes

(Witkowska & Woltering, 2014). These processes are

influenced by the plant’s morphological and

physiological characteristics, which are shaped by

pre-harvest environmental conditions (Watada et al.,

1996; Zou et al., 2019). Therefore, optimizing the

growth environment to preserve post-harvest quality

is essential for the food industry (Watada et al., 1996;

Fanourakis et al., 2016). Proper storage temperatures

(0–5°C) are crucial for maintaining the quality of both

whole and freshly cut produce (Tian et al., 2014;

Tsaniklidis et al., 2014).

In many developing countries, maintaining the

cold chain is challenging due to high costs and

unreliable electrical infrastructure (Mercier et al.,

2017). For example, only 15% of perishable food

products in China are transported using refrigerated

trucks (USDA, 2008), and India has only recently

developed a fully refrigerated supply chain (Dharni &

Sharma, 2015). Inadequate temperature control

affects not only transportation but also storage at

retail outlets and during commercial processing

(Likar & Jevšnik, 2006; Tian et al., 2014; Mercier et

al., 2017). Therefore, exploring ways to preserve

product quality under near-ambient conditions

remains a priority, especially in regions where cold

chain infrastructure is limited.

The shelf life of fruits and vegetables containing

chlorophyll is often constrained by the yellowing

caused by chlorophyll degradation (Tay & Perera,

2004). Browning, another common issue, results

from the oxidation of phenolic compounds (Fan &

Mattheis, 2000; Degl’Innocenti et al., 2005).

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) is the first key

enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of phenolics and

flavonoids via the phenylpropanoid pathway. PAL is

induced by stress, and the resulting phenolic

compounds offer antioxidant benefits for both plant

defense and human health (Fan & Mattheis, 2000;

Iakimova & Woltering, 2015; Tsaniklidis et al.,

2017). However, excessive phenolic accumulation

activates polyphenol oxidase (PPO), which catalyzes

the oxidation of phenols into quinones, leading to

undesirable browning. While PPO contributes to

plant defense against biotic stress, it also accelerates

post-harvest deterioration, affecting both the visual

appearance and nutritional value of produce

(Degl’Innocenti et al., 2005).

UVA radiation (320–400 nm), a primary

component of solar UV light, lies outside the spectral

range required for photosynthesis (Hogewoning et al.,

2012). As a result, its use in indoor cultivation has

been limited (Zhang et al., 2020). However, recent

from our laboratory shows that supplementing indoor

cultivation with UVA light (10 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹)

increases biomass and metabolite accumulation in

lettuce plants (Chen et al., 2019). Before commercial

application, it is essential to further evaluate the

impact of UVA light on post-harvest processes,

particularly its influence on shelf life.

The primary aim of this study is to investigate the

effects of different LED light treatments on the

quality, nutritional content, and shelf life of lettuce

during a 14-day storage period. Specifically, the study

seeks to evaluate key parameters such as weight loss,

pH, electrical conductivity, titratable acidity,

phenolic and flavonoid content, and nitrate levels

under varying LED light conditions. The objective is

to determine whether specific LED treatments can

enhance the post-harvest stability of lettuce,

preserving both its biochemical and sensory

attributes. It is hypothesized that certain LED light

treatments will be more effective in minimizing

nutrient losses and maintaining product quality, thus

extending the shelf life of lettuce. This research aims

to provide valuable insights into how LED lighting

can be optimized as part of post-harvest management

strategies, aligning with the growing demand for

high-quality, ready-to-eat produce in the modern food

industry.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

The experiment was conducted in March 2024 at the

Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture,

Çukurova University. A climate-controlled plant

growth chamber, measuring 5.0 m in length, 3.0 m in

width, and 2.6 m in height, was designed to function

as a plant factory for this study. The chamber was

equipped to regulate environmental factors essential

for optimal plant growth, including temperature,

humidity, lighting, CO₂ levels, and air circulation.

Effects of Different LED Light Spectra on the Shelf Life and Nutritional Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce in a Plant Factory

159

These conditions were meticulously controlled to

provide an ideal environment for plant development.

Lettuce plants were cultivated in a vertical

farming system within the climate-controlled

chamber. The system consisted of three stacked tiers

made from galvanized steel, with 40 cm of space

between each shelf, maximizing space efficiency.

The plants were grown using the Ebb-Flow

hydroponic technique, also known as the "Med-

Cezir" technique in Turkish. This method

periodically floods the plant roots with nutrient-

enriched water, followed by drainage, ensuring the

roots receive both optimal nutrition and aeration. The

model plant selected for the study was green-leaf

lettuce, a widely cultivated leafy vegetable, chosen

for its suitability for indoor farming and sensitivity to

controlled environmental conditions, making it ideal

for hydroponic research. Twelve days after sowing,

the lettuce seedlings were transferred to the Ebb-Flow

hydroponic system (Figure 1). Environmental

conditions in the plant factory were carefully

managed to ensure optimal growth. Daytime

temperatures were set at 25°C and nighttime

temperatures at 20°C, with a 12-hour light/12-hour

dark photoperiod. CO₂ levels were maintained at

approximately 400 ppm, and relative humidity was

kept between 60-70%. Lettuce plants were exposed to

three distinct LED lighting configurations:

LED1 = 70% red (610-720 nm) + 30% blue (450-

495 nm)

LED2 = Full PAR spectrum (400-700 nm)

LED3 = 65% red (610-720 nm) + 25% blue (450-

495 nm) + 5% white (400 475 nm) + 5% far red

(700-760).

The lettuce plants were cultivated under these

controlled conditions using hydroponic techniques

for 30 days before being harvested. After harvest, the

plants were stored in a cold storage facility at 8°C

with 60-70% humidity for 14 days. At the end of the

storage period, various parameters were measured,

including weight loss, chlorophyll content, phenol

and flavonoid concentrations, nitrate levels, and

mineral nutrient content. This approach enabled a

comprehensive evaluation of the effects of different

lighting conditions and storage durations on the post-

harvest quality of lettuce.

Measurements and Analyses Conducted in the

Experiment

Weight Loss: The fresh weight of the lettuce plants

was measured on days 1, 7, and 14 using a precision

scale. Based on these measurements, the percentage

of weight loss was calculated to assess moisture loss

over time.

Dry Matter (%): Dry matter content was determined

by measuring both the fresh and dry weights of the

plants. This analysis evaluated how much dry matter

was produced per 100 g of fresh lettuce under

different treatments.

Total Phenolic Content (mg GAE/100 g FW): The

total phenolic content in lettuce leaves was measured

using a modified version of the spectrophotometric

method described by Spanos and Wrolstad (1990).

Absorbance was recorded at 765 nm using a

spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Lambda EZ201

UV/VIS). Phenolic content was calculated from a

calibration curve prepared with gallic acid (Dasgan et

al., 2022; Ikiz et al., 2024).

Figure 1: Lettuce plants grown in a plant factory using a

hydroponic system under three different LED light spectra.

I-CRAFT 2024 - 4th International Conference on Research of Agricultural and Food Technologies

160

Total Flavonol Content (mg RUT/g FW): Flavonol

content in the lettuce leaves was measured according

to the method developed by Quettier-Deleu et al.

(2000). Absorbance readings were taken at 415 nm

using a spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Lambda

EZ201 UV/VIS), with flavonol content calculated

based on a calibration curve using rutin (Ikiz et al.,

2024).

Nitrate Content (ppm): A quarter of each lettuce

plant was used to determine nitrate levels using a

colorimetric method based on the salicylic acid

nitration procedure (Cataldo et al., 1975; Dasgan et

al., 2023a; Balik et al., 2025).

Total Soluble Solids (TSS) (%): The lettuce plants

were divided into four sections, and juice was

extracted from one-quarter of each plant using a

juicer. The soluble solid content (SSC) was measured

using a digital refractometer (Keskin et al., 2025).

EC and pH Measurements:To measure electrical

conductivity (EC) and pH, 100 ml of lettuce leaf juice

was extracted. The EC and pH values were recorded

using a combined pH and EC meter to evaluate the

effects of treatments on leaf nutrient balance (Keskin

et al., 2025).

Titratable Acidity (%): Titratable acidity was

measured by adding 50 ml of distilled water to 1 ml

of lettuce juice and titrating the mixture with 0.1 N

NaOH until the pH reached 8.1. The amount of NaOH

used was recorded to quantify acidity.

L, a, b Color Measurement: Lettuce color was

assessed using a digital colorimeter to measure

Hunter color parameters (L*, a*, b*). The colorimeter

was calibrated with a white ceramic plate (L = 96.96,

a = 0.08, b = 1.83) before each measurement. L*

represents brightness, a* measures red/green balance

(+a* for red, -a* for green), and b* indicates

yellow/blue balance (+b* for yellow, -b* for blue)

(Gould, 1977).

Nutrient Element Analysis: Macro- and

microelement content in lettuce leaves was analyzed

to determine the impact of different treatments on

plant nutrition (Dasgan et al., 2023b). Leaves were

washed with 0.1% detergent and rinsed three times

with distilled water to avoid contamination. The

cleaned leaves were dried at 65°C for 48 hours and

then ground. Samples were combusted at 550°C for 8

hours, and the resulting ash was dissolved in 3.3%

HCl. Potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg),

and sodium (Na) were measured using emission

mode, while iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn),

and copper (Cu) were analyzed using absorption

mode with an atomic absorption spectrometer.

Phosphorus (P) content was determined

spectrophotometrically using the Barton method.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted with three replicates.

Variance analysis (ANOVA) was performed using

JMP statistical software (Version 7.0, 2007).

Differences between treatments were assessed using

the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test, with

significance set at p < 0.05.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of the analyses, including weight loss,

soluble solid content (SSC), dry matter content, pH,

titratable acidity, total chlorophyll, total flavonoid,

total phenolic content, and macro- and microelement

concentrations in the lettuce samples, measured at the

beginning and on day 14 of storage, are summarized

in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5.

Effects of Biofertilizers on Leaf Nutritional and

Antioxidant Compounds

At the start of storage, SSC values ranged from 2.29

to 3.01 °Brix. The highest SSC value (3.01 °Brix) was

recorded in the 1st LED treatment on the first day,

while the lowest value (2.29 °Brix) was observed in

the 2nd LED treatment on day 14 (Table 1). A

significant decline in SSC values occurred over the

14-day storage period, likely due to the respiration

process, during which sugars and organic acids

degrade.

The pH values of lettuce samples, recorded both

post-harvest and during storage, are also presented in

Table 1. The pH ranged between 5.75 and 6.10, with

the highest value (6.10) observed in the 1st LED

treatment on day 14, and the lowest (5.75) recorded

in the 3rd LED treatment on day 1. A significant

increase in pH occurred by the end of the storage

period, consistent with previous studies. Hassenberg

and Idler (2005) reported that lettuce washed with tap

water showed a pH increase from 6.11 to 6.39 within

six days. King et al. (1991) observed a similar rise in

pH in lettuce stored at 5°C. Additionally, Allende et

al. (2004) and Martin-Diana et al. (2006) suggested

that microbial activity and production methods

contribute to pH increases during storage.

Electrical conductivity (EC) values, which reflect

changes in the mineral balance during storage, ranged

from 23.42 to 27.56 dS/m. On the first day, the lowest

EC value (8.60 dS/m) was measured under the 3rd

LED treatment, decreasing further to 6.56 dS/m by

day 14. This suggests a deterioration in the water and

Effects of Different LED Light Spectra on the Shelf Life and Nutritional Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce in a Plant Factory

161

mineral balance of the lettuce during storage. In

contrast, the 1st and 2nd LED treatments exhibited

higher EC values at the end of the storage period, with

the highest EC (27.56 dS/m) recorded under the 1st

LED treatment on day 14. These results indicate that

the 1st LED treatment was more effective in

preserving the mineral content and ion balance of the

lettuce plants during storage.

3.1 Implications for Post-Harvest

Quality Management

These findings underscore the importance of storage

conditions and light sources in maintaining the

mineral balance and overall quality of lettuce during

storage (Table 1). The ability of specific LED

treatments to manage EC fluctuations suggests that

targeted lighting strategies could play a crucial role in

maintaining post-harvest quality. The 1

st

LED

treatment, in particular, demonstrated potential for

preserving mineral content, highlighting the value of

optimized light conditions during storage. Research

like this contributes to improving storage practices,

enhancing quality parameters, and minimizing post-

harvest losses, thereby supporting more sustainable

agricultural practices.

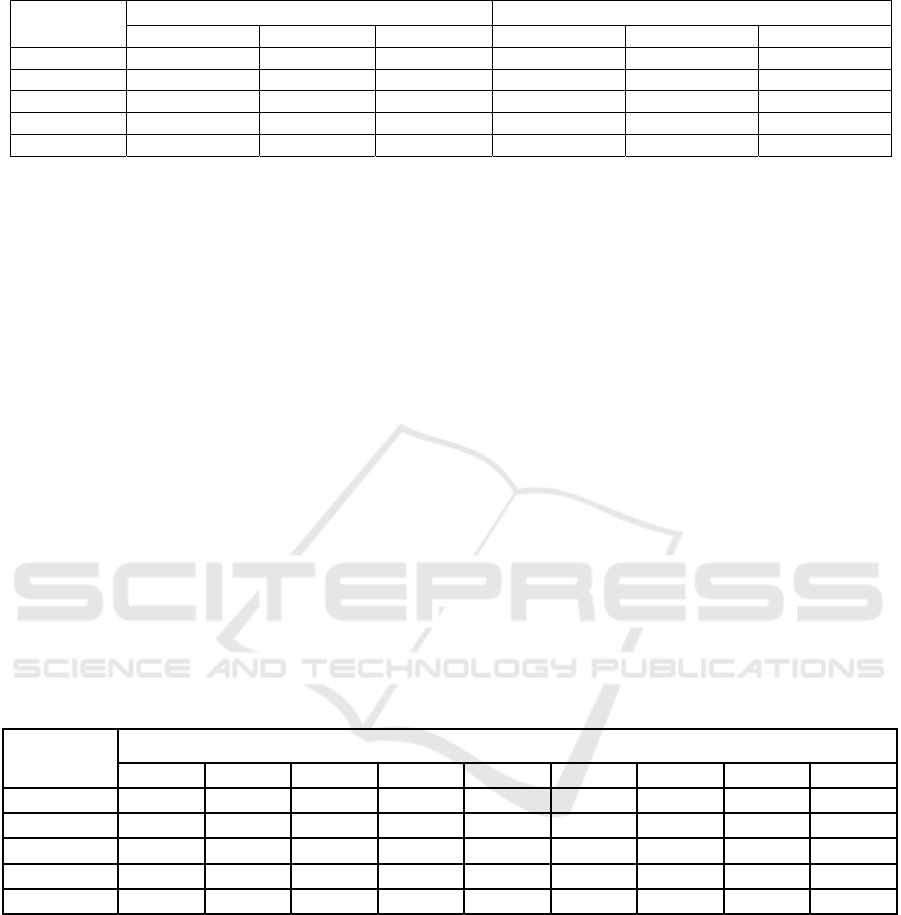

Table 1: The changes in pH, EC and TSS values of the lettuce samples during the storage period.

Treatment

pH EC TSS

Day 1 Day14 Loss % Day 1 Day 14 Loss % Day 1 Day 14 Loss %

LED

1

5,92 6,10 -3,03 8,43b 6,10b 27,56a 3,01a 2,83a 5,66bc

LED

2

5,88 6,13 -4,24 8,40b 6,14b 26,92a 2,90a 2,50b 13,79a

LED

3

5,75 6,01 -4,51 8,60a 6,58a 23,42b 2,50b 2,29b 8,41b

LDS

0,05

n.s n.s

4,138 0,095 0,107 0,811 0,244 0,263 0,252

P 0,1193 0,2220 0,6971 0,0043* <0.0001* <0.000* 0,0055* 0,0074* 0,0061

TSS: Total soluble solids. There is no significant difference between means with the same letter in the same column; LSD:

the least significant difference.

3.2 Titratable Acidity and Dry Matter

in Lettuce During Storage

The titratable acidity of lettuce samples during

storage ranged from 0.35 to 1.61 g/100g, with the

highest value (1.61 g/100g) recorded in the 1st LED

treatment on day 1 (Table 2). The lowest value (0.35

g/100g) was observed in the 2nd LED treatment on

day 14. By the end of the 14-day storage period, the

reduction in titratable acidity varied between 62.67%

and 77.01%, with the highest loss (77.01%) occurring

in the 1st LED treatment on day 1, while the lowest

reduction (62.67%) was recorded in the 3rd LED

treatment on day 14. These results suggest that the 3rd

LED treatment may be more effective in preserving

titratable acidity during storage. Scuderi et al. (2011)

reported similar findings for Duende lettuce, where

titratable acidity decreased from 1.01 g/L on day 1 to

0.42 g/L by day 9 during storage at 4°C.

At the start of storage, the total dry matter content

of the lettuce samples ranged from 3.02 to 4.56

g/100g (Table 2), with the highest value (4.56 g/100g)

recorded in the 1st LED treatment on day 1 and the

lowest value (3.02 g/100g) observed in the 2nd LED

treatment on day 14. Over the 14-day period, the dry

matter content ranged between 12.85 and 27.20

g/100g, with the highest reduction (27.20 g/100g)

observed in the 1st LED treatment and the lowest

reduction (12.85 g/100g) in the 3rd LED treatment.

These results align with those reported by Scuderi et

al. (2011), who found that the dry matter content of

Duende lettuce decreased from 3.78% on day 4 to

3.59% on day 9 during storage at 4°C. Similarly,

Wagstaff et al. (2007) reported an increase in dry

matter content from 3.2% to 4.3% in Cos lettuce and

from 2.6% to 3.7% in Lolo Rossa lettuce over 10 days

of storage.

The findings from this study indicate that while

the reduction in dry matter content during storage was

statistically significant, the extent of the reduction

was moderate (p < 0.0001). These results highlight

the importance of selecting appropriate lighting and

storage conditions to minimize the degradation of key

quality parameters, such as titratable acidity and dry

matter content, during post-harvest storage.

I-CRAFT 2024 - 4th International Conference on Research of Agricultural and Food Technologies

162

Table 2. Changes in dry matter and titratable acidity in lettuce during storage.

Practice

Acidity Dry Matter

Da

y

1 Da

y

14 Loss % Da

y

1 Da

y

14 Loss %

LED1 1.61a 0.37b 77.01a 4.56a 3.32a 27.20a

LED2 1.35b 0.35b 73.34a 3.94b 3.02b 15.43b

LED3 1.31b 0.50a 62.67b 3.45c 3.35a 12.85c

LDS

0.05

0.068 0.053 4.660 0.043 0.036 0.854

P <0.0001* 0.0009* 0.0007* <0.0001* <0.0001* <0.0001*

3.3 Effects of LED Lighting on Lettuce

Leaf Color Attributes

The statistical analysis revealed that the color

attributes of lettuce leaves, specifically L* (lightness)

and B* (yellow), were not significantly influenced by

the different LED treatments. However, a significant

difference was observed in the A* (red) parameter.

These findings suggest that LED lighting affects the

color characteristics of lettuce, as the lowest color

loss (5.8) was recorded under the 1st LED treatment

(Table 3).

For L* (lightness and brightness), the smallest

loss occurred in the 3rd LED treatment, while the

highest loss was observed in the 1st LED treatment.

Regarding the green color (-a*), the lowest loss was

also found in the 1st LED treatment, whereas the

greatest loss of yellow color (+b*) was recorded

under both the 2nd and 3rd LED treatments.

Kowalczyk et al. (2016) conducted a similar study

comparing different growing media, including rock

wool and cocopeat, within hydroponic systems

(Nutrient Film Technique, NFT), to cultivate two

types of head lettuce and one type of curly lettuce. In

their study, the color parameters of the Aficion

variety (Rijk Zwaan seed company) were measured.

For lettuce grown in rock wool, the values were 55.4

for L*, -14.8 for a*, and 39.1 for b*. In cocopeat, the

values were 63.2 for L*, -15.1 for a*, and 36.0 for b*.

In the NFT system, the measurements were 57.2 for

L*, -13.7 for a*, and 37.6 for b*.

In comparison, the L* values observed in this

study were lower than those reported by Kowalczyk

et al. (2016) in all three environments, indicating

reduced brightness and lightness. However, the a*

values recorded in this study were higher, while the

b* values were similar. Additionally, in Kowalczyk

et al.’s study, the tones of green in the Aficion variety

were assessed using a Minolta SPAD chlorophyll

meter, with values of 19.6 in rock wool, 24.2 in

cocopeat, and 19.6 in NFT.

Table 3. Effects of LED lighting on leaf color characteristics of curly lettuce cultivated in a hydroponic system.

Treatment

L, a, b color measurements

L1 L14 Loss % a1 a14 Loss % b1 b14 Loss %

LED

1

50,7 45,3 15,0 -11,6b -10,9b 5,8b 29,4 24,7 6,4

LED

2

49,9 44,6 10,8 -10,5ab -8,8a 14,8a 26,4 25,9 11,2

LED

3

49,5 41,8 10,5 -9,5a -8,2a 13,9ab 25,6 21,6 14,9

LDS

0,05

n.s n.s n.s

1,022 1,405 8,795

n.s n.s n.s

P 0,8723 0,4324 0,5529 0,0812 0,0026 0,0849 0,2690 0,1454 0,3514

L: Lightness (ranges from 0 [black] to 100 [white], a: Red/Green value (positive values indicate red, and negative values

indicate green), b: Yellow/Blue value (positive values indicate yellow, and negative values indicate blue). There is no

significant difference between means with the same letter in the same column; LSD: the least significant difference.

3.4 Changes in Phenolic, Flavonoid

Compounds, and Nitrate Levels in

Lettuce During Storage

At the beginning of storage, the total phenolic

compound values in lettuce samples ranged from

61.70 to 63.96 μg GAE/g, showing no statistically

significant differences. On the 14th day of storage,

these values ranged from 49.11 to 49.28 μg GAE/g,

with no significant changes observed (Table 4). The

lowest loss of phenolic compounds (20.24 μg GAE/g)

occurred under the 3rd LED treatment, while the

highest loss (23.20 μg GAE/g) was observed under

the 2nd LED treatment. Ke and Saltveit (1988) found

similar results in their study on iceberg lettuce,

attributing changes in phenolic content to

physiological responses related to infections and

tissue damage.

Effects of Different LED Light Spectra on the Shelf Life and Nutritional Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce in a Plant Factory

163

In this study, no significant differences in total

phenolic content were detected in the early days of

storage. It is likely that pre-treatment procedures

caused physiological responses and biochemical

reactions within the lettuce cells, contributing to

variations in phenolic content. Additionally,

enzymatic activity during storage may have

contributed to further reductions in phenolic levels.

Yamaguchi et al. (2003) observed that heat-treated

lettuces maintained stable phenolic content, while

untreated samples showed significant decreases over

time. Similarly, Altunkaya et al. (2009) reported a

decline in total phenolic content in lettuce during

storage.

Flavonoid content also varied based on the LED

treatments. On the first day of storage, the highest

flavonoid content (28.63%) was recorded under the

1st LED treatment, while the lowest (23.28%)

occurred under the 3rd LED treatment. After 14 days,

flavonoid content declined, with the 1st LED

treatment maintaining the highest level (22.24%) and

the 3rd LED treatment showing a reduction to

20.57%. The lowest flavonoid loss (11.67%) was

recorded under the 3rd LED treatment, while the

highest loss (22.61%) also occurred under the same

treatment. These findings highlight the role of

different LED light sources in influencing flavonoid

content, with the 1st LED treatment being particularly

effective in preserving flavonoids during storage. The

slower decline in flavonoid content under the 3rd

LED treatment also underscores the importance of

optimizing post-harvest storage conditions to retain

beneficial phytochemicals.

Nitrate content in the lettuce leaves showed

significant variation at the beginning of storage. The

lowest nitrate level (684 mg/kg) was observed under

the 2nd LED treatment, while the highest (978 mg/kg)

was recorded under the 3rd LED treatment. On the

14th day, nitrate levels again showed a similar

pattern, with the lowest value under the 1st LED

treatment and the highest under the 3rd LED

treatment (509 mg/kg). The most significant nitrate

losses occurred under the 3rd LED treatment (47

mg/kg) and the 1st LED treatment (42 mg/kg), while

the 2nd LED treatment showed the lowest nitrate loss

(26 mg/kg).

According to the Turkish Food Codex (2008), the

maximum allowable nitrate levels for lettuce vary

depending on the growing season and production

method. For lettuce harvested between October 1 and

March 31, the maximum nitrate levels are 4500

mg/kg for indoor-grown lettuce and 4000 mg/kg for

outdoor-grown lettuce. For the period between April

1 and September 30, the limits are 3500 mg/kg for

indoor-grown and 2500 mg/kg for outdoor-grown

lettuce. The nitrate levels recorded in this study

remained well below these thresholds, posing no

health risks to consumers. Zhang et al. (2018)

explored nitrate levels in hydroponically grown

lettuce using two lighting systems (fluorescent and

LED) with varying light intensities (150, 200, 250,

and 300 µmol/m²/s), red-to-blue light ratios (1:1 and

1:2), and lighting durations (12 and 16 hours). They

found that increasing light intensity from 150 to 300

µmol/m²/s and extending lighting duration to 16

hours reduced nitrate levels from 783 mg/kg to 359

mg/kg. In their LED treatments, nitrate levels

decreased as lighting duration increased, with nitrate

concentrations of 667 and 506 mg/kg for the 1:1 ratio

and 810 and 456 mg/kg for the 1:2 ratio.

In summary, the results from this study showed

higher nitrate levels at the beginning of storage,

which declined by the end of the 14-day period. These

findings align with those of Konstantopoulou et al.

(2010), who reported no significant changes in nitrate

levels after 10 days of storage.

Table 4. Changes in phenolic compound levels during the storage of lettuce.

Treatment

Total phenols

(mg GA 100g FW

−1

)

Total flavonoids

(mg RU 100g FW

−1

)

Nitrate

(mg kg FW

−1

)

Day 1 Day14 Loss % Day 1 Day 14 Loss % Day 1 Day 14 Loss %

LED

1

63,13 49,28 21,95 28,63a 22,24a 22,34a 800ab 454 42a

LED

2

63,96 49,11 23,20 27,16b 21,02ab 22,61a 684b 502 26b

LED

3

61,70 49,18 20,24 23,28c 20,57b 11,67b 978a 509 47a

LDS

0,05

n.s n.s n.s 1,41 1,56 3,05 224 n.s 13,34

P 0,1744 0,9077 0,2338 0,0002* 0,0964 0,0002 0,0491* 0,2021 0,0185*

FW: Fresh weigh, GA: Gallic acid, RU: Rutin There is no significant difference between means with the same letter in the

same column; LSD: the least significant difference.

I-CRAFT 2024 - 4th International Conference on Research of Agricultural and Food Technologies

164

3.5 Weight Loss Ratio in Lettuce

During Storage

In this study, the initial fresh weight of lettuce

samples ranged from 197 g to 216 g, with no

statistically significant differences observed among

the treatments. By the 14th day of storage, the fresh

weight values ranged between 194 g and 213 g, again

showing no significant differences (Figure 2). The

lowest weight loss (1.54%) was recorded in the

samples stored under the 1st LED light treatment,

while the highest loss (2.8%) occurred in the 2nd

LED light treatment. These results indicate that

different LED light treatments had a limited effect on

fresh weight loss during storage.

Figure 2. The effect of using different leds on the fresh weight loss of lettuce during storage.

From a scientific perspective, these findings

suggest that LED light treatments did not

significantly influence water loss, cellular respiration,

or metabolic rates during storage. This highlights the

idea that LED lights are more effective during the

plant growth phase, rather than post-harvest. In

storage, environmental factors such as temperature

and humidity play a more critical role in preserving

fresh weight. Although LEDs can provide various

wavelengths to enhance plant growth, they do not

appear to significantly impact the metabolic activities

of lettuce during storage.

The absence of statistically significant differences

in fresh weight between the beginning and end of the

14-day storage period supports the conclusion that

LED treatments do not directly affect water loss.

Most of the water content in lettuce is stored

within leaf tissues, and water loss is more closely

related to environmental conditions, such as

temperature and humidity, rather than the type of

lighting used during storage. The fresh weight losses

observed, ranging from 1.54% to 2.8%, further

highlight the limited effect of different LED light

treatments on storage performance. These low

percentages suggest that LED lighting has a

negligible impact on metabolic processes during

storage. Instead, the findings emphasize the

importance of optimizing storage conditions to

maintain product quality.

These results align with the findings of Charles et

al. (2018), who reported that lettuce stored under low

light intensity (or in darkness) experienced less than

5% fresh weight loss, whereas high light intensity led

to weight losses of up to 30%. Their study

underscores the role of light intensity in influencing

moisture loss and spoilage. Low light or dark

conditions can effectively reduce water loss, while

exposure to high light intensity accelerates

dehydration and compromises product quality. In

summary, while LED lighting may offer advantages

for plant growth, its influence on post-harvest weight

loss is minimal. This study demonstrates that

environmental conditions, particularly temperature

and humidity, are the primary determinants of lettuce

quality during storage. Therefore, optimizing storage

practices remains essential for extending the shelf life

and maintaining the quality of lettuce.

Effects of Different LED Light Spectra on the Shelf Life and Nutritional Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce in a Plant Factory

165

3.6 Nutrient Loss in Lettuce Under

Different LED Treatments

At the end of the 14-day storage period, nitrogen,

calcium, and magnesium levels showed lower loss

rates in the 3rd LED group compared to the 2nd LED

group (Table 5). Specifically, the loss rates for the 3rd

LED group were 1.72% for nitrogen, 12% for

calcium, and 11% for magnesium, whereas the 2nd

LED group exhibited higher losses of 8.22%, 14%,

and 17%, respectively. Excluding potassium from the

analysis, the lowest overall loss rate (2.17%) was

recorded in the 2nd LED group. However, potassium

loss rates varied, with the 1st and 3rd LED groups

showing 13% and 3.51% loss, respectively. In terms

of microelements, plants exposed to the 2nd LED

treatment exhibited the highest nutrient loss rates

after 14 days of storage compared to those under LED

1 and LED 3. However, when copper was excluded,

the nutrient loss associated with the 2nd LED

treatment remained significant. The copper loss rate

for LED 2 was 15.48%, compared to 12.67% in LED

1 and LED 3.

For manganese, the highest loss rate (59.95%)

was observed in the 2nd LED group, while the 1st and

3rd LED groups exhibited lower losses of 47.38% and

40.76%, respectively (Table 6). Similarly, iron losses

were greatest in the 2nd LED group (59%), with LED

1 and LED 3 showing losses of 52% and 51%,

respectively. In terms of zinc, the 2nd LED treatment

resulted in the highest loss rate (9.27%), while LED 1

and LED 3 had slightly lower losses of 7.29% and

7.55%, respectively. These findings demonstrate that

the type of LED treatment significantly influences the

retention of essential nutrients in lettuce during

storage, with the 3rd LED treatment generally

yielding lower loss rates for most nutrients. This

aligns with previous research highlighting the impact

of light quality on the stability of nutrients in post-

harvest produce (Zhang et al., 2018; Charles et al.,

2018). Further research could focus on optimizing

LED wavelengths and intensities to minimize nutrient

loss during storage, thereby improving the quality and

extending the shelf life of lettuce and similar crops.

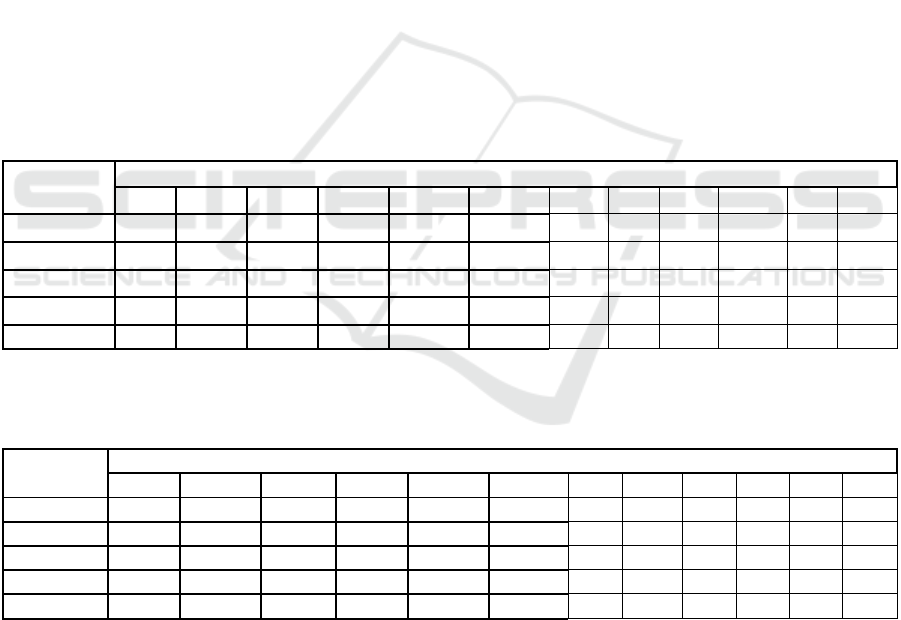

Table 5. Changes in macroelement levels in lettuce during storage.

Treatment

Macro Elements

N1 N 14 Los% K 1 K 14 Loss % Ca1 Ca 14 loss % Mg 1 Mg 14 Loss %

LED

1

5.42 5.33 1.59b 8.48a 7.38b 13a 3.72 2.63 29a 0.46c 0.46 -0.43b

LED

2

5.60 5.15 8.22a 8.49ab 8.30a 2.17b 3.18 2.72 14b 0.57a 0.47 17a

LED

3

5.06 4.98 1.72b 8.84a 8.53a 3.51b 3.02 2.65 12b 0.54b 0.47 11a

LDS

0.05

n.s n.s

8.14 0.34 0.64 7.34 0.21 0.46 12.54 0.011 0.029 6.05

P

0.518 0.7618 0.0066 0.0776 0.0107* 0.0093* 0.0006* 0.8307 0.0313* <0.0001* 0.5493 0.0009*

There is no significant difference between means with the same letter in the same column; LSD: the least significant

difference.

Table 6. Changes in microelement levels in lettuce during storage.

Treatment

Micro Elements

Cu1 Cu 14 loss % Mn 1 Mn 14 loss % Fe 1 Fe 14 loss % Zn 1 Zn 14 loss %

LED1 25.3 21.33a 15.48 86.33 45.33ab 47.38ab 95a 44a 52 68 62 7.29

LED2 22.6 22.0a 2.84 95.00 38.00b 59.95a 86ab 39b 59 65 60 9.27

LED3 20.6 17.3b 12.67 90.66 53.33a 40.76b 79b 34c 51 63 58 7.55

LDS0.05 n.s 2.732 n.s 9.126 10.09 14.99 12.32 3.36 n.s 6.39 n.s n.s

P 0.4197 0.0120* 0.3679 0.1460 0.0278* 0.0519 0.0617 0.0011* 0.1310 0.2383 0.1985 0.5042

There is no significant difference between means with the same letter in the same column; LSD: the least significant

difference.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that different LED

treatments had limited effects on parameters such as

total phenolic content, L (lightness) and B

(yellowness) color values, and weight loss during

storage (p > 0.05). However, LED treatments

significantly influenced key quality indicators,

including pH, electrical conductivity, acidity, dry

I-CRAFT 2024 - 4th International Conference on Research of Agricultural and Food Technologies

166

matter content, a (redness) color value, total soluble

solids, flavonoid concentration, and nitrate levels.

These results highlight the selective impact of

LED lighting on the biochemical and physical

properties of lettuce during storage. The findings

underscore the potential of specific LED treatments

in preserving nutritional and sensory qualities,

contributing to extended shelf life. This is

particularly relevant for fresh-cut and pre-packaged

lettuce products, which are increasingly favored by

urban consumers seeking convenience. In conclusion,

this study provides valuable insights into how LED

lighting can be leveraged to improve post-harvest

management strategies for lettuce. Future research

should focus on optimizing LED wavelengths and

integrating them with other preservation techniques

to maximize both quality and shelf life, meeting the

growing market demand for fresh, ready-to-eat

produce.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the

TAGEM/21/AR-GE/03 project, which enabled the

cultivation of lettuce in the plant factory system.

REFERENCES

Allende, A., Aguayo, E., & Artés, F. (2004). Microbial and

sensory quality of commercial fresh processed red

lettuce throughout the production chain and shelf life.

International Journal of Food Microbiology.

Altunkaya, A., Becker, E. M., Gökmen, V., & Skibsted, L.

H. (2009). Antioxidant activity of lettuce extract

(Lactuca sativa) and synergism with added phenolic

antioxidants. Food Chemistry, 115(1), 163–168.

Balik, S., Elgudayem, F., Dasgan, H. Y., & others. (2025).

Nutritional quality profiles of six microgreens.

Scientific Reports, 15, 6213.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85860-z

Charles, F., Nilprapruck, P., Roux, D., & Sallanon, H.

(2018). Visible light as a new tool to maintain fresh-cut

lettuce post-harvest quality. Postharvest Biology and

Technology, 135, 51–56.

Dasgan, H. Y., Aldiyab, A., Elgudayem, F., & others.

(2022). Effect of biofertilizers on leaf yield, nitrate

amount, mineral content and antioxidants of basil

(Ocimum basilicum L.) in a floating culture. Scientific

Reports, 12, 20917. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-

022-24799-x

Dasgan, H. Y., Kacmaz, S., Arpaci, B. B., İkiz, B., &

Gruda, N. S. (2023a). Biofertilizers improve the leaf

quality of hydroponically grown baby spinach

(Spinacia oleracea L.). Agronomy, 13(2), 575.

https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13020575

Dasgan, H. Y., Yilmaz, D., Zikaria, K., Ikiz, B., Gruda, N.

S. (2023b). Enhancing the yield, quality and antioxidant

content of lettuce through innovative and eco-friendly

biofertilizer practices in

hydroponics. Horticulturae, 9(12), 1274.

Degl’Innocenti, E., Guidi, L., Pardossi, A., & Tognoni, F.

(2005). Biochemical study of leaf browning in

minimally processed leaves of lettuce (Lactuca sativa

L. var. Acephala). Journal of Agricultural and Food

Chemistry, 53(26), 9980–9984.

Degl’Innocenti, E., Pardossi, A., Tognoni, F., & Guidi, L.

(2007). Physiological basis of sensitivity to enzymatic

browning in lettuce, escarole, and rocket salad when

stored as fresh-cut products. Food Chemistry, 104(1),

209–215.

Dharni, K., & Sharma, R. K. (2015). Supply chain

management in the food processing sector: Experience

from India. International Journal of Logistics Systems

and Management, 21(1), 115–132.

DuPont, M. S., Mondin, Z., Williamson, G., & Price, K. R.

(2000). Effect of variety, processing, and storage on the

flavonoid glycoside content and composition of lettuce

and endive. Journal of Agricultural and Food

Chemistry, 48(9), 3957–3964.

Fan, X., & Mattheis, J. P. (2000). Reduction of ethylene-

induced physiological disorders of carrots and iceberg

lettuce by 1-methylcyclopropene. Postharvest Biology

and Technology, 35(2), 151–160.

Fanourakis, D., Bouranis, D., Giday, H., Carvalho, D. R.,

Nejad, A. R., & Ottosen, C. O. (2016). Improving

stomatal functioning at elevated growth air humidity: A

review. Journal of Plant Physiology, 207, 51–60.

Gao, E., Cui, Q., Jing, H., Zhang, Z., & Zhang, X. (2021).

A review of application status and replacement progress

of refrigerants in the Chinese cold chain industry.

International Journal of Refrigeration, 128, 104–117.

Hassenberg, K., & Idler, C. (2005). Influence of washing

method on the quality of prepacked iceberg lettuce.

Agricultural Engineering International: The CIGR

Ejournal, Manuscript FP 05 003, Vol VII, November.

Hogewoning, S. W., Wientjes, E., Douwstra, P.,

Trouwborst, G., Van Ieperen, W., Croce, R., &

Harbinson, J. (2012). Photosynthetic quantum yield

dynamics: From photosystems to leaves. The Plant

Cell, 24(5), 1921–1935.

Iakimova, E. T., & Woltering, E. J. (2015). Nitric oxide

prevents wound-induced browning and delays

senescence through inhibition of hydrogen peroxide

accumulation in fresh-cut lettuce. Innovative Food

Science & Emerging Technologies, 30, 157–169.

İkiz, B., Dasgan, H. Y., & Gruda, N. S. (2024). Utilizing

the power of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on

reducing mineral fertilizer, improved yield, and

nutritional quality of Batavia lettuce in a floating

culture. Scientific Reports, 14, 1616.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51818-w

Ke, D., & Saltveit, M. E. (1988). Plant hormone interaction

and phenolic metabolism in the regulation of russet

Effects of Different LED Light Spectra on the Shelf Life and Nutritional Quality of Hydroponically Grown Lettuce in a Plant Factory

167

spotting in iceberg lettuce. Plant Physiology, 88(4),

1136–1140.

Keskin, B., Akhoundnejad, Y., Dasgan, H. Y., & Gruda, N.

S. (2025). Fulvic acid, amino acids, and vermicompost

enhanced yield and improved nutrient profile of soilless

iceberg lettuce. Plants, 14(4), 609.

https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14040609

King, A. D., Jr., Magnuson, J. A., Török, T., & Goodman,

N. (1991). Microbial flora and storage quality of

partially processed lettuce. Journal of Food Science,

56(2), 459–462.

Konstantopoulou, E., Kapotis, G., Salachas, G.,

Petropoulos, S. A., Karapanos, I. C., & Passam, H. C.

(2010). Nutritional quality of greenhouse lettuce at

harvest and after storage in relation to N application and

cultivation season. Scientia Horticulturae, 125(2), 93–

101.

Kowalczyk, K., Mirgos, M., Bączek, K., Niedzińska, M., &

Gajewski, M. (2016). Effect of different growing media

in hydroponic culture on the yield and biological

quality of lettuce (Lactuca sativa var. capitata). Acta

Horticulturae, 1142, 105–110.

Likar, K., & Jevšnik, M. (2006). Cold chain maintenance in

food trade. Food Control, 17(2), 108–113.

Martinez, I., Ares, G., & Lema, P. (2008). Influence of cut

and packaging film on sensory quality of fresh-cut

butterhead lettuce. Journal of Food Quality, 31(1), 48–

66.

Mercier, S., Villeneuve, S., Mondor, M., & Uysal, I. (2017).

Time–temperature management along the food cold

chain: A review of recent developments.

Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food

Safety, 16(4), 647–667.

Özgen, M., & Scheerens, J. C. (2006). Bazı kırmızı ve siyah

ahududu çeşitlerinin antioksidan kapasitelerinin

modifiye edilmiş TEAC yöntemi ile saptanması ve

antikanser özelliklerinin tartışılması. II. Üzümsü

Meyveler Sempozyumu, Tokat.

Özgen, M., & Tokbaş, H. (2007). The effect of illumination

on the antioxidant capacity of fruit tissues in Amasya

and Fuji apples. Journal of the Faculty of Agriculture,

Giresun University, 24(2), 1–5.

Saglam, S. (2007). The effect of jam production processes

on phenolics and antioxidant capacity in anthocyanin-

rich mulberry, cherry, and cornelian cherry fruits

(Master’s thesis, Selçuk University, Institute of

Science, Department of Food Engineering, Konya).

Scuderi, D., Restuccia, C., Chisari, M., Barbagallo, R. N.,

Caggia, C., & Giuffrida, F. (2011). Salinity of nutrient

solution influences the shelf-life of fresh-cut lettuce

grown in floating system. Postharvest Biology and

Technology, 59(2), 132–137.

Tay, S. L., & Perera, C. O. (2004). Effect of 1-

methylcyclopropene treatment and edible coatings on

the quality of minimally processed lettuce. Journal of

Food Science, 69(2), fct131–fct135.

Tian, W., Lv, Y., Cao, J., & Jiang, W. (2014). Retention of

iceberg lettuce quality by low-temperature storage and

postharvest application of 1-methylcyclopropene or

gibberellic acid. Journal of Food Science and

Technology, 51, 943–949.

Tsankilidis, G., Delis, C., Nikoloudakis, N., Katinakis, P.,

& Aivalakis, G. (2014). Low-temperature storage

affects the ascorbic acid metabolism of cherry tomato

fruits. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 84, 149–

157.

Wagstaff, C., Clarkson, G. J. J., Rothwell, S. D., Page, A.,

Taylor, G., & Dixon, M. S. (2007). Characterization of

cell death in bagged baby salad leaves. Postharvest

Biology and Technology, 46, 150–159.

Zhang, W., & Jiang, W. (2019). UV treatment improved the

quality of postharvest fruits and vegetables by inducing

resistance. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 92,

71–80.

Zhang, Y., Kaiser, E., Zhang, Y., Zou, J., Bian, Z., Yang,

Q., & Li, T. (2020). UVA radiation promotes tomato

growth through morphological adaptation leading to

increased light interception. Environmental and

Experimental Botany, 176, 104073.

I-CRAFT 2024 - 4th International Conference on Research of Agricultural and Food Technologies

168