Development of Nederlandsch Dutch East Indies Nature Protection

Association 1912–1938

Muhammad Zanu, Nurzengky Ibrahim

a

and Kurniawati

b

History Education Studi Program, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Nederlandsch–Indische Vereeniging Tot Natuurbescherming, Nature Conservation, Dutch East Indies,

National Park, S.H Koorders, Bogor Botanical Garden.

Abstract: This article aims to examine the Nederlandsch–Indische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming (Association for

the Protection of Nature) as the first Indonesian organization involved in nature conservation between 1912

to 1938. The five components of the historical research method are applied in this study. The research study’s

findings Nederlandsch- Indische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming association is an organization that is

involved in the first nature conservation efforts in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). Dr. S.H. Koorders

established Nederlandsch- Indische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming in 1912 in Batavia, Jakarta, as a

forum for those concerned about the environment in the Dutch East Indies at the time. The conclusion of the

research study is that the Association of the Nederlandsch–Indische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming was

the initial milestone in the development of an official forum with the first legal entity in the Dutch East Indies

(Indonesia) that fought for nature conservation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Indonesia's very rich biodiversity is apparently

fragile from greedy human hands. Currently,

Indonesia has an official institution that manages and

monitors biodiversity under the Ministry of

Environment and Forestry (LHK) as a state

institution that pays attention to Indonesia's natural

conditions. Apart from that, there are private

institutions that also pay attention to biodiversity in

Indonesia, such as WALHI (Wahana Lingkungan

Hidup Indonesia/Indonesian Forum for

Environment) and the international private institution

Greenpeace which is active in voicing Indonesia's

natural environmental problems. However, during

the Dutch East Indies colonial period, there were no

official government or private institutions that paid

serious and consistent attention to the natural

conditions of the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia).

Then on July 22, 1912 an association called

Nederlandsch–Indische Vereeniging tot

Natuurbescherming (Natural Protection Association

of the Dutch East Indies) was founded as the first

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-4624-4121

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7916-091X

nature conservation association in the Dutch East

Indies based on the concerns of Dr. S.H Koorders as

a naturalist and botanist related to the massive

exploitation of nature in the Dutch East Indies for the

mercantilism interests of the Dutch colonial

government. This association is also used as a forum

and tool for the struggle of its members who are

concerned about maintaining forest areas which are

considered to have the potential for unique flora and

fauna, geological phenomena and beautiful natural

panoramas in the form of Natuurmonument areas or

Nature Reserves and Wild Reservaat (Wildlife

Reserves).

What makes researchers interested in researching

this association is the courage and success of its

breakthrough as the first private association to ask the

Dutch colonial government in 1913 to designate 12

areas whose natural aesthetics need to be protected on

the island of Java, namely, Rawa Danau, Ujung

Kulon Peninsula, Pulau Panaitan, Krakatau Island

(Banten), Papandayan Crater (West Java), Bromo

Sand Sea, Nusa Barung, Ijen Crater, Ijen Plateau and

Purwo Peninsula (East Java) to become natural

Zanu, M., Ibrahim, N. and Kurniawati,

Development of Nederlandsch Dutch East Indies Nature Protection Association 1912–1938.

DOI: 10.5220/0013490000004654

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science (ICHELS 2024), pages 165-174

ISBN: 978-989-758-752-8

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

165

monuments that should not be disturbed (Anonim,

1986).

2 RESEARCH METHOD

The writing research method used in this research is

a historical research method by applying five aspects,

namely topic selection, source collection, data

verification, interpretation, and historiography. The

method used is adapted to the descriptive- narrative

approach, literature study and rewriting of the

information that has been obtained which is then

combined in this research. (Kuntowijoyo, 2013).

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Background to the Establishment of

the NIVN Association

Human exploitation of nature has occurred for

thousands of years since social changes occurred in

humans. The social changes that occur generally

adapt the patterns of change from primitive to

agrarian society, to industrialism and now to an

electronic information society (Wiratno, 2004). This

pattern has also developed to this day and has an

influence on the Eco-friendly lifestyle which

suggests conservation and development ideas that

emerge from the same intellectual ideas for human

progress. Businesses across the western world have

discovered consumer demand for “eco-friendly” and

“ecological” products which has opened up new

commercial opportunities. (Cribb, 2007). The

evolutionary changes experienced by humans over

thousands of years have produced various kinds of

technology to support human life to develop. Without

realizing it, mastering this technology allows modern

humans to conquer nature while accelerating the

depletion of natural resources. The emergence of a

new world view of the relationship between humans

and nature, closely related to the Anglophile

traditions of Natural History and Hunting. Because at

that time, natural history and hunting traditions were

two great interests of elite society in Europe and

North America. At the end of the 19th century, many

British government administrative employees had

hunting skills, which at that time was considered a

masculine sport. The study of natural history in

Europe and America was closely linked to the

exploration and expansion of their colonies in the

tropics and gaining access to exotica was the

privileged domain of the aristocrats. This eventually

brought scientists, collectors, writers and adventurers

of all classes into elite circles and linked enthusiasm

for natural history with exploration and trade in the

tropics (Jepson & Whittaker, 2002).

The development of the idea of nature

protection in the international arena in the 19th

century was also based on the idea that it was

necessary to protect nature (Flora, Fauna & Natural

Landscape) as a form of human kindness towards

nature (humanity) which eroded the stigma of

humans as supernatura beings (Jepson &

Whittaker, 2002). Furthermore, the emergence of

the idea of the world's first modern nature

conservation movement was born in the United

States. Starting from the inspiration and dreams of

two artists, namely, William Wordsworth and

George Catlin, about desires them to protect their

favorite place in the American West so they can

continue to enjoy it. Finally, on April 20, 1832, a

small step from President Andrew Jackson, the 7th

President of the United States, made a policy to

protect a hot spring in the Arkansas Mountains

which

became

known

as

the

Hot

Springs

Reservation. Some thirty years later, on June 30,

1864, President Abraham Lincoln pressed for a

measure to protect an area that included Yosemite

Valley and Mariposa Grove in the state of

California. Later this landscape was called

Yosemite National Park. (Kusumasumantri, 2016).

Then in September 1870, Washburn & Doane went

on an expedition to Yellowstone. As they relax and

reflect around a wilderness campfire, they are amazed

by Yellowstone's spectacular views. Then, after

considering the possibility of protecting the area to

avoid private exploitation. In the utmost altruism,

Washburn & Doane agreed that Yellowstone's

magnificent geysers, waterfalls, and canyons should

be preserved as a national park. This proposal was

quickly presented to the political brass and on March

1, 1872, Congress established Yellowstone Park as

the world's first "National Park," covering over two

million acres located mostly in the northwest corner

of present-day Wyoming (Holland & Houck, 2013).

At that time the "Yellowstone Manifesto" could be

considered a moral, economic and political statement

as a sign of the beginning of the modern era regarding

the management of natural resources in the form of

land, landscapes and cultural sites managed in an

ideological relationship (National Parks) between

governments. with society. Since then, the idea of

national parks began to spread from the United

States to other corners of the world, such as Canada

(1885), New Zealand (1894), Australia, South Africa

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

166

and Latin American countries (1898) (Wiratno,

2004).

Meanwhile in Europe there is growing concern

among German forestry circles over the clear-cutting

policy which is destroying the beauty of the

landscape and destroying forest areas with

extraordinary scientific value and special aesthetics.

Germany's response aims to promote rational

resource planning through the inventory and

protection of natural attributes of interest. The

preparatory step is making a vegetation map. The

first map published was for France in 1897 with

similar maps published for Germany, England,

Switzerland and North America in the first decades of

the twentieth century. Then, an idea emerged from a

German naturalist named Dr. Hugo Conwentz about

the formation of Naturdenkmal which he promoted

when giving lectures in European cities in 1903-

1908. Conwentz's vision of Naturdenkmal as a place

for contemplation of nature, an antidote to urban life,

where people could develop a greater appreciation for

their homeland. This catalyzed the creation of

institutions to designate and manage natural

monuments. Conwentz was appointed Commissioner

for the Care of Natural Monuments by the Prussian

State in 1906. Then Naturdenkmal support

associations began to emerge in various European

countries, in France (1901), Switzerland (1909)

and England (1912) (Jepson & Whittaker, 2002).

In the Dutch East Indies, there were several

events that gave rise to the emergence of the spirit of

nature conservation. First, in 1860 The Mountain

Park was established in Cibodas which is also part of

the 's Lands Plan, which aims to store a collection of

highland alpine and sub-tropical tropical mountain

plants, especially Kina. Based on this proposal,

Gouvernement Besluit was issued on 17 May 1889

No. 50 which shows an area of 280 Ha is under the

supervision of the Director of the Botanical Gardens.

In 1889, forest was set aside in the Gede-Pangrango

Mountains area, which extended to a height of 2,400

meters, to be combined with the Cibodas Botanical

Gardens. The proposal for this forest section was

prepared by Prof. Dr. Melchior Treub through his

letter dated 2 August 1888 No.229 addressed to the

Director of Education, Culture and Industry

(Directeur van Oorderwijs, Eredienst en Niverheid)

(Kusumasumantri, 2016). The Dutch East Indies

Government accepted this proposal, by issuing a

Decree of the Dutch East Indies Government (Besluit

van Gouvernement van Nederlandsch- Indie) dated

17 May 1889 No. 50 which stated that "Research has

shown that the highland flora in Java in the Botanical

Gardens includes The proposed expansion to 280

Ha needs to be protected and under the supervision

of the Director of the Cibodas Botanical Gardens,

especially those located on the northeastern slopes of

the Mount Gede forest area. Second, a catastrophic

event decreased the population of birds of paradise

in nature. As reported by the former Chief Resident

of Ternate, F.S.A. de Clercq in an 1890 article:

” Now that birds are almost never found along the

coast and the kill has moved inland, it will not be long

before nothing remains of these most glorious

products of the Creator, a delight to Ornithology and

a wonder to the whole world.” (Roelants, 1899).

In 1894, thanks to encouragement both by this

warning and by reports from the Dutch press which

reached the Indies in editions of foreign newspapers

such as the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant. In

November 1895, the Minister of Colonies in The

Hague received a letter signed by executives of the

Bond ter Bestrijding eener Gruwelmode (Association

for Combating Obnoxious Fashions) and others,

deploring the Roofjacht (Loot Hunt) of what world

environmentalists dubbed “The Most Beautiful Bird

In the World” and urged the minister to prevent it

(Cribb, 1997). In January 1898 the Colonial

Government sent Dr. J.C. Koningsberger, an

agricultural zoologist who went to the Bogor

Botanical Gardens to seek scientific input on the

causes of the extinction of the bird of paradise. The

input regarding the bird of paradise then became an

idea for drafting laws to protect other fauna. In

January 1898 the Colonial Government sent Dr.

J.C. Koningsberger, an agricultural zoologist, to the

Bogor Botanical Gardens to seek scientific input on

the causes of the extinction of the bird of paradise.

The input regarding the bird of paradise then became

an idea for drafting laws to protect other fauna.

3.2 Development of the NIVN

Association 1912 – 1919

The establishment of the Nederlandsch Indische

Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming association

cannot be separated from the great role and struggle of

Dr. S.H Koorders was very persistent in forming an

association that could accommodate people who had

an interest in protecting the natural beauty of the

Dutch East Indies. Koorders was born in Bandung,

November 29 1863, he was the only child of Maria

Henriette Boeke and Dr. Daniel Koorders. When he

was 6 years old, his father died so Koorders and his

mother returned to Haarlem, Netherlands. The

motivation for Koorders' love of Indies nature began

in the city environment which the Mayor of Haarlem,

F.W. van Eeden was beautified with rare plants,

Development of Nederlandsch Dutch East Indies Nature Protection Association 1912–1938

167

fostering Koorders'interest in nature and plants.

Figure 1: Dr. Sijfert Hendrik Koorders

In 1884 Koorders first served in the Dutch East

Indies as Houtvester. For 12 years he conducted

research in Java, Sumatra and Sulawesi. Then in 1910

he was placed in Bogor and received a new

assignment in the herbarium section of the Bogor

State Botanical Gardens. His deep concern as a true

friend of nature towards areas damaged by forest

utilization activities which received little attention

from the Dutch East Indies Government, made him

think of establishing a nature protection association

to preserve nature. (Kusumasumantri, 2014)

On July 22, 1912, in Buitenzorg (Bogor),

Koorders founded an association to accommodate

people who cared and were concerned about the

natural conditions of the Dutch East Indies. When it

was first established (unofficially), Koorders invited

his colleagues who were also staff members at the

Bogor Botanical Gardens, several prominent

scientists, botanists and private plantation owners, as

well as several important names in the Dutch East

Indies who were involved in the initial founding of

the association.

Since its inception, Koorders was aware that the

association he founded could be considered a threat to

the world of plantations and agriculture in the Dutch

East Indies. In that era, many private plantations

invested and had activities in the Dutch East Indies

and were strongly supported by the government

because they were considered the main source of state

income (Wiratno, 2004). So, Koorders tried to reach

out to Tuan Teun Ottolander, a director of a well-

known coffee plantation in the Besuki area (East

Java) who also served as chairman of the

Nederlandsch-lndische Landbouw Syndicaat (Dutch

East Indies Agricultural Syndicate). They met when

Koorders was on duty collecting plant collections for

his work and at the Bogor Botanical Gardens (Van

der Poel, 2019).

A week later, on August 28, 1912, Koorders

wrote another introductory article about the newly

founded association. The article was published under

the auspices of the Dutch East Indies Agricultural

Syndicate with the title "Oprichting Eener

Nederlandsch-Indische Vereeniging tot

Natuurbescherming door Dr. S. H. Coorder S”. This

publication was deliberately chosen to remove the

association from the perceived threat of plantation

owners. Establishment of the association and

willingness to collaborate with the Koninklijke

Natuurkundige Vereeniging van Nederlandsch- Indie

& Natuurhistorische Vereeniging van Nederlandsch-

Indie as representatives of intellectuals and the

Nederlandsch Indische Landbouw Syndicaat as

representatives of Dutch East Indies plantations to

support the noble task of nature conservation so as

not to sacrifice profits from possible forest

exploitation by plantations and also so that there is no

friction between the two conflicting organizations

(Koorders, 1912).

The establishment of the Nederlandsch

Indische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming

association subsequently received a good response

from various groups and agencies in the Dutch East

Indies and abroad. The association also reported on

its founding in various newspapers such as,

Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, De Indische Mercuur, De

Locomotief, De Koerier, Soematra Bode, Deli

Courant, even the Dutch newspaper, Algemeene

Handelsblad also reported on the founding of the

association. The working methods of the NIVN

association are also based on Conwentz's philosophy

of Naturdenkmäler, which does not seek to protect

completely natural animal species or areas, but only

some special and extraordinary botanical or

geological phenomena. The establishment of the

NIVN association was also inspired by the

achievements of the Association for the Preservation

of Natural Monuments in the Netherlands in

protecting natural monuments in the Netherlands.

The NIVN Association hopes that similar success

can also be achieved in the Dutch East Indies. Even

though they have the same goals, in their

implementation there are large and substantial

differences between the two associations. One of the

biggest differences with the Association for the

Preservation of Natural Monuments in the

Netherlands is the relationship between the NIVN

association and the Dutch East Indies government.

The NIVN Association in its implementation seems

to be more dependent on both regional and national

governments compared to its Dutch counterpart

(Boomgaard, 1999).

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

168

On February 3, 1913 the NIVN association

officially published articles of association and

bylaws which had the legal entity of the Dutch East

Indies government "Statuten Der Nederlandsch-

Indische Vereeniging Tot Natuurbescherming -

Goedgekeurd bij Besluit van den Gouverneur-

Generaal van Nederlandsch-Indië van February 1913

No. 36” which consists of 27 articles. In article

3, paragraphs 1-4, several association privileges

regarding conservation activities in the Dutch East

Indies are stated: 1) Associations can systematically

collect regulations and general information data from

natural monuments. 2) Propose requests for

conservation activities to authorized officials. 3)

Prevent other interests in natural monument areas in

the Dutch East Indies. 4) Providing legal advice for

violations involving the destruction of natural

monuments. This made the NIVN association a

government advisory institution in making policies

and nature conservation activities in the Dutch East

Indies.

On March 31, 1913, the NIVN association took

concrete action by inviting cooperation with the

Depok city government, successfully establishing the

first natural monument in the Dutch East Indies.

The location of this small natural monument is

not far from the Depok train station, which is a

former forest owned by a VOC employee, Mr.

Cornelis Chastelein, which was donated to his freed

slaves to be looked after because this place is often a

stopping place for migratory birds (Chastelein,

1714). The Depok natural monument has an area of

6 hectares and is considered the first nature reserve

(Natuurmonument) in the Dutch East Indies or it

could be said to be the first official nature reserve in

Indonesia (now). This is based on a written

cooperation agreement for the management of

natural monuments between the chairman of the

NIVN association, Dr. S.H. Koorders with the head of

the Depok city government, Heeren G. Jonathan on

March 31, 1913. This designation refers to the Dutch

East Indies nature protection plan and meets the

requirements as a nature reserve (Natuurmonument).

(Kusumasumantri, 2014). Until now, the Depok

nature reserve which was previously guarded and

managed by the association has become a RTH

(Green Open Space) in the middle of a densely

populated area of Depok city which functions as a

bird migration site and water catchment area.

The association's persistence in lobbying the

government to establish natural monuments in the

Dutch East Indies was highly appreciated by the

Governor General of the Dutch East Indies at that

time, A.W.F. Idenburg. The award is based on

experiences when A.W. F Idenburg. was still

serving as Minister van Kunciien (Minister of

Colonial State), at that time Koorders had just been

assigned to the Dutch East Indies for the first time in

the Dutch East Indies and compiled data on Java

island plants, Exurtion flora von Java (1907-1909). In

1916, the Government finally accepted suggestions

and considerations from the association to designate

the establishment of natural monuments in these

areas to protect the natural wealth of the Dutch East

Indies. The Dutch East Indies government finally

issued the Natural Monuments Law

(Natuurmonumenten Ordonantie) on March 18,

1916, which was published in the Dutch East Indies

State Gazette (Staatsblad van Nederlandch-Indie)

No. 278 of 1916 as the basis used by the Governor

General to designate natural monuments in the

following years. The basis for the appointment of the

monument ordinance initiated by Dr. S.H. Koorders

and thanks to the association's persistence in lobbying

the government in starting awareness in preserving

the very rich nature of the Dutch East Indies. This is

stated in the State Gazette of the Dutch East Indies

1916 No.278 (Natuurmonumenten Ordonantie van

18 March 1916, Staatsblad van Nederlandsch-Indie

1916 No.278) (Koster, 1922). Three years later in

1919, the Dutch East Indies Government re-issued 2

Governor General's Decrees designating the areas

proposed by the association as natural monuments at

55 locations, of which in the 1919 Staatsblad No.90

there were 24 locations and in the 1919 Staatsblad

No.392 there were 31 locations. location. This was a

great success for the NIVN association during the

chairmanship of Dr.S.H Koorders, because several

location names listed in Staatsblad 1919 No.90 and

Staatsblad 1919 No.392 were the result of submitting

association applications to the government in the

1913 and 1917 annual reports (Boomgaard, 1999).

Applications for conservation activities in areas

that require natural protection with biodiversity

potential which began in 1916, finally met with

success in February 1919 with the publication of the

Decree of the Governor General of the Dutch East

Indies dated 21 February 1919 No. 6, with Staatsblad

1919 No. 90 which determined 24 locations to be

inaugurated as natural monuments as a legal basis for

designating natural protected areas in the Dutch East

Indies (Koster, 1922). The Natural Monuments

Ordinance of 1919 was the earliest regulation in

Indonesia that explained the concept of conservation

areas which was later updated and adapted to Law No.

5 of 1990 concerning Conservation of Biological

Natural Resources and Their Ecosystems.

The success of the association has achieved

Development of Nederlandsch Dutch East Indies Nature Protection Association 1912–1938

169

satisfactory results in proposing natural protected

areas as natural monuments with real action from the

government in issuing the Natural Monument Laws

of 1916 and 1919. However, unfortunately, at the end

of 1919, the association had to experience a major

loss due to the death of Dr. S.H. Koorders as founder

and first chairman of the NIVN association.

Koorders died on 16 November 1919 at the age of 56

at the Cikini Hospital in Weltervreden and was

buried in Batavia. News of Koorders' death was

also

published in the forestry magazine "TECTONA,

DEEL XII, 13e Jaargang 1920." belonging to the

association VABINOI (Vereeniging van

Ambternaren bij het Boschwezen in Nederlandsch

Oost Indie - Association of Forest Service

Employees in the Dutch East Indies) in 1920 in

Oorspronkelijke Bijdragen Dr. S.H. Coorders written

by E.H.B. Brascamp, author of the most journals on

forestry in Boschwezen who is also a member of the

NIVN association. Brascamp wrote in full about

Koorders' life and activities during his lifetime

(Brascamp, 1920). So, in honor of Koorders, he was

appointed chairman for life. Then as a form of

appreciation for Koorders, the Houtvesters and

association members submitted a request to the

Dutch East Indies government to create a special

natural monument using Koorders' name.

This request was also conveyed to the new

chairman of the NIVN association, namely, K.W.

Dammerman, who then asked the Dutch East Indies

government to consider a small island called Nusa

Gede in the middle of Lake Panjalu (now Situ

Lengkong), to the east of the Priangan Residency

(Ciamis) which had also previously been designated

as a natural monument in the 1919 Staatsblad No.90

It is proposed that it later become Koorders Island and

Koorders Natural Monument (Kusumasumantri,

2014). Two years later, the Decree of the Governor

General of the Dutch East Indies was issued on 16

November 1921 No.60, State Gazette 1921 No.683

(Besluit van den Gouverneur-Generaal van

Nederlandsch-Indie, Staatsblad van Nederlandsch-

Indie 1921 No.683) designating the Nusa Nature

Reserve Gede on Panjalu Lake, Priangan Residency,

so that it will henceforth be named "Koorders Island

and Koorders Natural Monument". As another form

of honoring Koorders, the date and month of the

Governor General's Decree was enshrined the same as

the date and month Koorders died (Kusumasumantri,

2014).

3.3 Development of the NIVN

Association 1920 – 1938

All members of nature protection associations at

home and abroad feel the loss of Koorders.

Furthermore, based on the agreement of all members

of the association, appointed Dr. K.W. Dammerman

as the new NIVN association chairman. At that time

Dammerman also served as head of the Buitenzorg

Zoological Museum. In the subsequent management

of the organization, Dammerman entrusted his

botanical work to Dr. Van Steenis and Dr. H.J. Lam

both show great attention to the issue of nature

protection. Dammerman feels that his position as

chairman of the association carries a great

responsibility in continuing the ideals left behind by

Koorders. During Dammerman's tenure the

association mademany changes and new

breakthroughs for the world of conservation in the

Dutch East Indies in the future. Apart from that, at

this time the association also began to actively voice

environmental protection in the Volksraad (People's

Council) with the joining of the Regent of Cianjur,

R.T.A. Suria Nata Atmaja and Dr. JC Koningsberger,

into the NIVN association and at the same time they

are members of the Board (Boomgaard, 1999).

In 1920, the government issued another law

regarding the location of new natural monuments

which was a continuation of Staatsblads 1919 No.90

with a different Governor General's Decree.

Published through the Decree of the Governor

General of the Dutch East Indies dated 9 October

1920 No.46, State Gazette 1920

Figure 2: Dr. K. W Dammerman

No.736 concerning Natural Monuments.

Designation of locations of natural monuments

(Besluit van den Gouverneur-Generaal van

Nederlandsh-Indie, Staatsblad 1920 No.736.

Natuurmonumenten. Aanwijzing van terreinen als

Natuurmonumenten). The number of natural

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

170

monuments mentioned in Staatsblad 1920 No.736 is

8 locations.

Table 1: numbers of natural monument mentioned

Staatsblad 1920 No.736

No Name Wide Location

1. Tjeding 2 Ha Bondowoso

2. Kawah Idjen-

Merapi

Oengoep-

oengoep

2.560 Ha Banjoewangi

3. Poerwo 40.000 Banjoewangi

4. Djati Ikan 1.950 Ha Banjoewangi

5.

Noesa

Baroeng

6.000 Ha Djember

6. Pringombo I-

II

12-46 Ha Wonosobo

7. Lorentz- Nieuw

Guinea

- Papua

Then the association applied to the government to

protect natural monuments from mining destruction.

The Dutch East Indies Government issued a Decree

of the Governor General dated 16 November 1921

No.60, Dutch East Indies State Gazette 1921 No.683

concerning

Natural Monuments and Mining. Designation of

locations as natural monuments and prohibition of

mining research and/or clearing by private parties

(Koster, 1922).

In the early days of Chairman Dammerman's term

of office, the focus of the pattern of applying for areas

for natural monuments at that time was still the same

as the pattern during Koorders' previous term of

office. Applications for area designation still use the

pattern of considering the aesthetics of the area, the

richness of flora or the unique geological conditions

of the area only. The pattern of considering the

designation on this aspect is probably because it is

still based on the Naturdenkmäler theory concept

adopted by Koorders (put forward by Conwentz)

where fauna is barely or not at all mentioned as

Naturdenkmäler (Koorders, 1912).

In the 1924 report there were also other

indications that fauna protection was becoming a

subject of increasing importance for the association.

For example, new natural monuments are no longer

only considered from the angle of flora and geology,

but also mention the importance of certain animals.

For example, the Saobi natural monument site has

been proposed by the association for the protection

of several fauna including, "Sea doves, deer and wild

cattle". Then in the following years, the association

began to draw attention to the "giant lizard" fauna

found in Lesser Sunda (Nusa Tenggara), specifically

on the islands of Komodo and Rinca, which will later

have a special natural monument or national park for

this fauna. The same thing also happened in the

British Colonies in Southeast Asia, the Federated

Malay States (British Malay), the British colonial

government had attempted to implement the "Indian

Forest Act and Wild Birds and Animals Protection

Act" of 1912, namely the Law on Forest Protection

and Animal Hunting. used to be applied in India

(British Maharaj). In British Malay there is also a

nature protection association called "Society for The

Preservation of The Fauna of The Empire" which was

founded in Africa in 1903. They noted that in 1923

in British Malay there were several nature reserves

such as, Serting, Sungei Lui, Krau, and Mount Tahan

which protects the Gaur, Sumatran Rhino and Asian

Elephant. Meanwhile in the French Colonies in

Southeast Asia (Tonkin, Annam, Laos, Cambodia

and Cochin-China) hunting regulations were also

regulated in 1925 to protect elephants (Brower,

1931).

Thanks to the efforts of associations and

cooperation with the international community in

nature protection. A regulation on the protection of

wildlife and hunting was born in 1924. This was a

new, more concrete effort to save a number of species

that were threatened with extinction and to protect

other species that were useful in nature so that they

could maintain the ecosystem and not be threatened

with extinction. In the 1924 Wildlife and Hunting

Protection Law, this time it lists in detail all the

animals that must be protected in the Dutch East

Indies, such as: 8 species of mammals (including

orangutans) and 53 species or groups of birds. In

addition, large mammal protection in Java is only

given to the Javan Rhino and the Silvery Javan

Gibbon. Meanwhile, for provinces outside Java, there

are 11 additional species or groups of animals,

including elephants.

Figure 3: Rhinoceros Sumatranensis.

Development of Nederlandsch Dutch East Indies Nature Protection Association 1912–1938

171

Then in Java, a hunting ban was introduced for

hunting deer, antelope, mouse deer and buffalo. The

same restrictions apply to a number of birds

throughout the Dutch East Indies. The Wildlife

Protection and Hunting Act of 1924 also introduced

the ownership of deeds or shooting licenses that

hunters were required to have in order to prevent the

rise of illegal hunting. The most prominent feature of

the 1924 Ordinance was the total ban on the export of

dead or live protected animals or parts of their bodies

which was a revision of the 1909 Ordinance.

Although both ordinances had prohibited the

ownership of protected animals, by implication the

level of illegal exports was not sufficiently regulated

to make this clause effective. The rapidly increasing

export figures of protected animals and their products

clearly show that protection without an export ban is

almost meaningless. (Dammerman, 1929). In 1929

the VI Pacific Science Congress was held in

Bandung. Dammerman, as a member of the NIVN

association and during his ten-year term as chairman

of the association, was appointed to prepare a major

review of nature conservation in the Dutch East Indies

at the convention by delivering a paper entitled

"Preservation of Wildlife and Nature Reserve in the

Nederlandsch Indie" (Boomgaard, 1999). A journal

containing explanations of the natural conditions of

the Dutch East Indies and the fauna in it. In this

journal, a report also recorded data on the number of

animal exports from the Dutch East Indies since 1909.

The combination of Kies' motion and Dammerman's

presentation then made the government try to improve

the welfare of fauna by publishing Staatsblad 1931

No. 134, namely a regulation on the protection of

fauna along with hunting prohibitions and export

provisions. Several months after Staatsblad 1931 No.

34 regarding animal protection orders came out, the

government also issued new regulations to further

clarify the prohibition on hunting and exploitation of

animals to minimize the possible impact of the export

and hunting of wild animals in the Dutch East Indies.

The regulations issued are Staatsblad 1931 No.

266, Dierenbeschermigverordening dated 25 June

1931 contains 27 types of animals including

orangutans, tapirs, rhinos, elephants and Komodo

dragons. Meanwhile, hunting was also tightened

again by issuing Staatsblad 1931 No. 133,

Jachtordonnantie by clarifying the types of hunting

activities ranging from types B – E with a fine of £. 10

- £. 200 and prohibits the taking of various live

animals for export and keeping and prohibits the

taking of animal hunting products ranging from

animal skins, ivory and fur. (Department van

Landbouw, 1932) Then the Government and the

Association agreed to issue the 1932 ordinance, so

that animals could have a special place that was safe

from the threat of hunters by issuing the Ordonnantie

Natuurmonumente regulations. Dierenbescherming

1932 to designate several areas to become Wildlife

Reserves. The 1932 animal protection ordinance

became the initial reference for the modern (post-

independence) Indonesian government in creating

several more specific legal products to manage and

protect typical Indonesian animals. For example, in

the management of nature reserves and tourist forests

during the era of President Soeharto, 30 Nature

Protection and Preservation Sections were formed.

On the island of Java there are three sections in West

Java, two sections in Central Java, three sections in

East Java, and 22 other sections spread across each

province, one section each. Meanwhile, the number

of protected fauna is 75 species, which refers to the

Wild Animal Protection Ordinance 1931 No. 134,

Wild Animal Protection Regulations 1951 No. 266,

Decree of the Minister of Agriculture No.

327/1972, no. 66/1973 and No. 421/1980.

(Kusumasumantri, 2016)

The association experienced many changes in

membership structure after Dammerman's

chairmanship, after which the association slowly

began to merge with the Dienst Boschwezen (Forestry

Service) and 'Lands Plan Certainin. Because on

average most of the association members also work at

the institution. So it is not surprising if we look at the

1924 Statutes (ADART 1924) as stated in article 8

that members who are also members of workers'

organizations will be regulated by the central

government administration. (NIVN, 1924).

According to researchers, this also influenced the

change in location of the association's office address,

which was previously in Batavia, moving to

Buitenzorg. Apart from that, the annual report also

began to write the name of the governor general who

was serving at that time as a Beschermer (Protector).

In 1934, this event shook the world. When several

Americans led by Lawrence Griswold and William

Harkness. They are graduates of Harvard University

who came to Southeast Asia to carry out arrests

several Komodo dragons. led by Lawrence Griswold

and William Harkness (Barnard, 2011).

In 1936 the governor general celebrated the

association's jubilee anniversary which had been

around for 25 years. Then a senior associate, as well

as a person who once served as the first secretary of

the association, namely, Mr C. Van den Bussche will

retire and return to the Netherlands. So the association

conveyed generally in the report. Apart from that, in

the report there is also Dr. K, W Dammerman who

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

172

received the title of honorary member of the

association and announced that he would also retire

in a few years (NIVN, 1938). It was also stated that

several new members had joined from other

prestigious organizations such as Dr. W. F. De

Priester, chairman of the Dutch East Indies Hunting

Association, then there was Mr. E.

J. F. Van Dunné, a Dutch Lawyer and Company

Director for New Guinea and chairman of the

Mountain Sports Association. It was also mentioned

that in 1937 members of another association, namely,

R.A.A.A. Soeria Nata Atmadja, who served as

Regent of Tjiandjoer as well

as

the

association's

representative

in the Volksraad, had to resign from

membership. The association's eleventh annual report

for 1936 – 1938 was made into a book entitled "3

Jaren Indische Naturleven" or "3 Years of Indian

Natural Life".

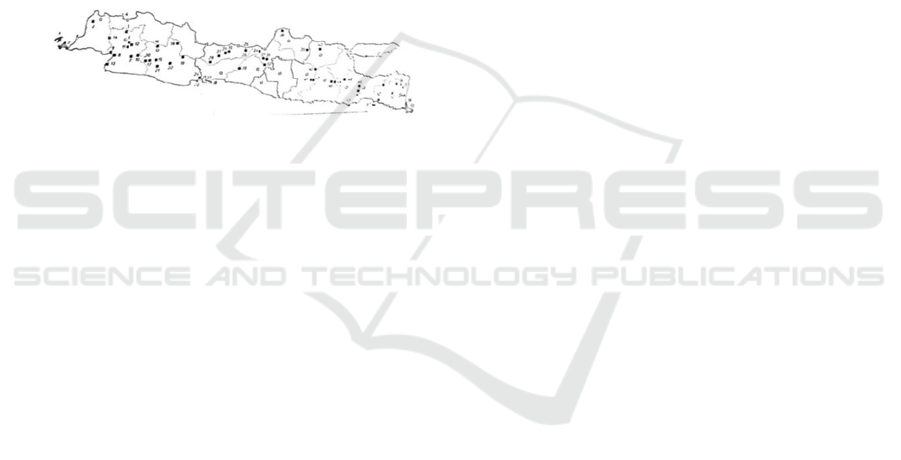

Figure 4: Location of natural monuments and wildlife

reserves on the island of Java

Book of 3 Jaren Indische Naturleven is also a

record of the association's last report that researchers

found. This is the reason for researchers to limit their

research to 1938, because the association's annual

report is important to see the development of the

association. If there is any possibility of literature

about the association being found after 1938, most of

it is in the form of journals or personal literature

belonging to association members.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Nederlandsch Indische Vereeniging tot

Natuurbescherming or the Dutch East Indies Nature

Protection Association is the initial milestone of a

group of people who have empathy and concern for

the fragile natural riches of the Dutch East Indies

from the greedy hands of humans. This association

was founded in 1912, spearheaded by Dr. S.H

Koorders, a naturalist and botanist who was amazed by

the rich nature of the Dutch East Indies. Koorders got

the idea of Naturdenkmal when he was on leave in the

Netherlands in 1903 and attended a lecture given by

Conwentz. From there, Koorders was inspired to

apply this concept to the Dutch East Indies, where

nature was very rich. So Koorders immediately

gathered his colleagues and invited other residents of

the Dutch East Indies who had concern and sympathy

for the natural conditions of the Dutch Indies. On July

22, 1912, as a result of this association, an association

was born called Nederlandsch Indische Vereeniging

tot Natuurbescherming.

The NIVN Association also has the main

objectives in their movement, namely, compiling an

inventory of forest trees, submitting proposals to

companies, government officials and private

individuals, as well as petitioning the Dutch East

Indies government to take steps to preserve natural

monuments. Strengthening good public opinion about

nature conservation and most importantly creating a

Dutch East Indies natural monument. The world of

international conservation also influences the

association's work methods and practices. According

to researchers, this is normal because a concept to

protect nature only emerged at the beginning of the

century – 19 and many other ideas about how to

protect nature have not yet developed, especially for

the size of the Dutch East Indies as a colony, of course

its movements are limited and limited by the mother

country as the owner of the highest authority. Apart

from that, there is no harm for researchers in

following developments in the world of

international conservation so that conservation

in the Dutch East Indies is not left behind and can

keep up with the times in accordance with

environmental issues that were developing at that

time.

Since its founding from 1912 – 1938 the

association has helped the government as an advisory

board and considered the designation of natural

monument areas and wildlife reserves. It is recorded

that during the term of office of the chairman of the

Koorders from 1912 – 1919 he produced legal

products for nature conservation in the Dutch East

Indies, namely, the Natural Monuments Law of 1916

concerning area protection and the 1919 Natural

Monuments Law which designated more than 50

areas to be made into natural monuments. While the

development of the association from 1920 – 1938,

many other important events occurred during that

time. The Law Prohibiting Mining in Natural

Monuments of 1921 was created to clarify the purity

of natural monuments. Then the Law on the

Protection of Animals, Mammals, Birds and Hunting

Procedures of 1924 was also created to ensure that

fauna living in natural monuments were protected

from hunting activities. Then the most important

thing is the Natural Monuments and Animal

Protection Law of 1932 which became the legal basis

for the establishment of a new type of natural

Development of Nederlandsch Dutch East Indies Nature Protection Association 1912–1938

173

monument specifically for fauna with a wider area

called Wildreservaten (Wildlife Reserve). It was

recorded that in 1936 there were 17 wildlife reserves

in the Dutch East Indies.

Research on the NIVN association is limited to

1938, marked by the last primary historical data found

in the form of published magazine reports, namely "3

Jaren Indische Natuurleven, Opstellen Over

Landschappen, Dieren En Planten, Tevens Elfde

Verslag/ 3 Years of Indies Natural Life, Essay

Landscapes, Animals and Plants, as well as the

Eleventh Association Report (1936-1938)” after

which the existence of the association is unknown, but

the its members still continue to work in the world of

nature conservation in the Dutch East Indies, for

example Mr. Hora Sicama, who still serves as head of

Houtvester and other members who continue to

explore the Dutch East Indies. Most of the

association's original report journals are located in the

Netherlands, it would be good if we could find out

whether the association still existed in the following

year or not because the Dutch East Indies government

in 1941 was still making conservation policies in the

form of the Java and Madura Hunting Ordinance

(Jachtordonnantie Java en Madoera 1940 Staatsblad

1939) and the Nature Protection Ordinance

(Natuurbeschermings Ordonnantie) 1941 Staatsblad

1941 indicates that there is still possible

breakthroughs made by the association and its

influence on nature conservation policy in the Dutch

East Indies before the arrival of the Japanese in 1942.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge Social Science and

Law Faculty of Universitas Negeri Jakarta which

already funded this publication in the year 2024.

REFERENCES

Anonim. (1986). Sejarah Kehutanan Indonesia Jilid 1,

Praserjarah-1942.

Barnard, T. P. (2011). Protecting the Dragon: Dutch

Attempts at Limiting Access to Komodo Lizards in the

1920s and 1930s.

Boomgaard, P. (1999). Oriental nature, its friends and its

enemies: Conservation of nature in late-colonial

Indonesia, 1889-1949. Environment and History, 5(3),

257.

Brascamp, E. H. B. (1920). Dr. S. H. Koorders door E. H.

B, Brascamp: Overdruk uit het Boschbouwkundig

Tijdschrift, Tectona Deel XIII Aflevering 5.

Brower, B. (1931). Organisatie Van De

Natuurbescherming In De Verschillende Landen.

Nederlandsche Commissie Voor Internationale

Natuurbescherming.

Chastelein, C. (1714). Het Testament Van Cornelis

Chastelein in leven “Raad ordinaris van Indie”

Overleden te Batavia den 28 Juni 1712. Bibliothieek

KITLV.

Cribb, R. (1997). Birds of Paradise and Environmental

Politics in Indonesia 1890- 1931.

Cribb, R. (2007). Conservation in Colonial Indonesia.

Interventions, 9(1), 49–61.

Dammerman, K. W. (1929). Presevation Of Wild Life And

Nature Reserves In The Netherlands Indies.

Holland, J. L., & Houck, J. (2013). Western Historical

Quarterly ,. 14201(435), 2003–2006.

Jepson, P., & Whittaker, R. (2002). Histories of Protected

Areas: Internationalisation of Conservationist Values

and Their Adoption in the Netherlands Indies

(Indonesia). Environment and History, 8(2), 129–172.

Koorders. (1912). Oprichting Eener Nederlandsch-

Indische Vereeniging tot Natuurbescherming door Dr.

S. H. Koorders.

Koster, S. et. a. (1922). Verzameling van de voornaamste

Nederlandsch-Indische Wetten, Reglemaent en

Verordeningen.

Kuntowijoyo. (2013). Pengantar Ilmu Sejarah. Tiara

Wacana.

Kusumasumantri, P. (2014). Peranan Dr.S.H Koorders

dalam Sejarah Perlindungan Alam di Indonesia.

Kusumasumantri, P. (2016). Sejarah 5 Taman Nasional

Pertama.

NIVN. (1938). 3 Jaren Indische Natuurleven. GEVESTIGD.

Roelants, H. A. (1899). De Huisvriend - Nieuwe serie.

Jaargang 1 bron.

https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_hui002189901_

01/colofon.php

Van der Poel, T. (2019). De groene gordel van smaragd De

Nederlands-Indische natuurbescherming tussen 1912

en 1935.

Wiratno, D. (2004). Berkaca di Cermin retak: Refleksi

Konservasi dan Implikasi Bagi Pengelolaan Taman

Nasional (Sri Nurani Kartikasari (ed.); 2nd ed.).

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

174