Social Science in Action: A Study of the Paradox of

Democracy in Civil Liberties in the Digital Era

Ubedilah Badrun

1

a

and Airlangga Pribadi

2

b

1

Doctoral Candidate in Social Sciences, Universitas Airlangga,, Dharmawangsa Dalam Street, Surabaya, Indonesia

2

Universitas Airlangga, Dharmawangsa Dalam Street, Surabaya, Indonesia

Keywords: Digital Democracy, Civil Liberties, Digital Literacy, Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA).

Abstract: This study analyzes the decline of civil liberties in the digital democracy era by examining Indonesia's

democracy paradox. Using a qualitative approach and Van Djik's (1993) Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA),

this research explores the connection between digital democracy and social criticism. While digital democracy

theory suggests that technology enables greater public participation in expressing aspirations and government

criticism, the case of Indonesia shows the opposite. Indonesia's democracy index dropped by 0.18 compared

to the previous year, indicating that increased social media use has not strengthened democracy or civil

liberties. The findings reveal that the rise in social media users does not correlate with an improved democracy

index. This highlights the need for wisdom in using digital platforms to foster meaningful democratic progress.

Furthermore, the government appears to lack sufficient digital democracy literacy, which hinders its ability

to harness technology for improving civil liberties. Therefore, while internet penetration grows, efforts must

focus on responsible use of social media and strengthening digital literacy to enhance Indonesia's democratic

quality.

1 INTRODUCTION

Claim euphoria to dominate digital democracy by

using digital direct democracy and listening to

aspirations online (Hilbert, 2009). As such, digital

democracy is evolving with a more objective

approach to breaking the dichotomy of direct and

representative democracy in a democratic but digital

way. Levy (2021) introduces digital media or new

media as content in the form of a combination of data,

text, sound and various types of images stored in

digital format that can be disseminated through

broadban optical cable-based networks, satellites or

microwaves. Digital media has unique characteristics

compared to traditional media. This is because digital

information is easily changed and adapted in various

forms. In addition, digital media is a new way for

someone to gain new experiences in relation to media

technology. Digital media also has the ability to

determine the public agenda by selecting and

emphasising certain issues.. Van Dijk (2012) said that

the role of digital participation initiatives from civil

society can outweigh government initiatives,

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0000-0000-0000

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0000-0000-0000

although their influence on political decisions is

debatable. In addition, the government does not yet

have adequate mechanisms and capacity to deal with

increased digital participation (Judhita, 1925). Digital

participation in this society has negative and positive

impacts according to the theme raised. In addition,

not all countries are open to digital media. The

paradox in digital democracy in China is seen through

the use of technology for social surveillance. This is

supported by the study of Zhang and Fung (2013)

shows that there was propaganda by a Chinese media

TV station on one of its citizens who had the initiative

to organize Shanzai online. Unfortunately, the site

could not appear because it was blocked by the

government. While digital platforms offer spaces for

public participation, many are also used to monitor

and restrict free speech, creating a tension between

individual creativity and government control. Thus,

such public participation is better known as digital

democracy.

Digital democracy is the participation of citizens

in the political process through digital platforms such

as online voting, online petitions and discussion

234

Badrun, U. and Pribadi, A.

Social Science in Action: A Study of the Paradox of Democracy in Civil Liberties in the Digital Era.

DOI: 10.5220/0013412200004654

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science (ICHELS 2024), pages 234-240

ISBN: 978-989-758-752-8

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

forums. Digital media encourages transparency and

accountability in government by facilitating access to

information and public scrutiny. Therefore, digital

democracy provides new opportunities for

participants in digital media to actively participate in

decision-making, and increase their voice in the

political process. Several previous studies have

shown that various digital democracies can enable

easier participation. One of them is the hashtag of

#MahsaAmini. The hashtag is an attempt by

protesters through social media such as X to oppose

several points of criticism about the government in

Iran, one of which is the use of the hijab (Kermani,

2023). #MahsaAmini shows the integration of

technology in the process of digital democracy. Thus,

campaigns are not only conducted directly in the field

but also through social media. According to Nyoka

and Tembo (2022) Digital democracy became an

alternative for people making collective efforts to

demonstrate against the government such as

#ThisFlag during the Tajamuka riots in Zimbabwe.

Lutscher and Ketchley (2023) shows the other side of

digital democracy, where many anti-regime social

media users in Egypt have new accounts by hiding

their information to avoid online codes of conduct.

Tseng (2023) also introduced gamifiction democracy

as digital democracy through the application of game

elements to increase engagement and participation.

These gamified democracies include DecideMadrid

and vTaiwan. Both initiatives focus on public

participation and the use of technology to improve

decision-making processes. DecideMadrid is a

platform developed to engage the citizens of Madrid

in proposing ideas and participating in discussions on

important issues. In addition, vTaiwan is a tool

developed by an online platform with the aim of

allowing citizens to provide input and participate in

the legislative process.

In Japan, their government is able to integrate

information and communication technology as an

instrument of citizen participation, and it seems that

local governments are more capable than the central

government (Takao, 2004). Therefore, there is an

attempt to build a new form of participatory

democracy that can complement the government

representation system. On the other hand, people in

South Korea were able to influence the cancellation

of beef imports by lighting candles and sharing the

event on the internet (Kim and Kim, 2009). In

contrast to Malaysia, research of Majid (2010) shows

that the state civil apparatus is not fully prepared and

trusts public aspirations conveyed through digital

technology. Studies of digital democracy in these

countries generally illustrate that ideas, criticism or

control can be easily conveyed to political elites or

those in power in today's digital society. If the

government does not immediately respond to

criticism and aspirations, the issue can develop into a

digital-based protest movement. In Indonesia, there

has been a feud between the Komisi Pemberantasan

Korupsi or Corruption Eradication Commission

(KPK) and the police. Then, a narrative emerged in

the public arena about 'lizard versus crocodile' (cicak

versus buaya) (Lim, 2013). The KPK is symbolized

like a lizard, and the police is symbolized like a

crocodile. This community protest movement spreads

through digital means with the hashtag #saveKPK.

Thus, in 2012 this movement protected the KPK from

weakening effort.

The emergence of public criticism using digital

media continues to occur in Indonesia. The most

recent example was the student and people movement

in September 2019 using the hashtag

#Reformasidikorupsi (reform is corrupted) to reject

the weakening of the KPK. The KPK is about to be

weakened by revising the KPK Law by the DPR

(People's Representative Council). This student and

people protest movement received wide support

nationwide in almost all provinces in Indonesia,

although it was later not heard by the DPR and the

President. The digital-based movement also occurred

in October 2020, which also occurred widely in all

provinces; the people and students expressed their

rejection of the ratification of the Omnibus Law on

Job Creation (Anggraeni and Rachman, 2020). ot

half-heartedly, this movement is also supported by

Nahdlotul Ulama and Muhammadiyah Islamic

organizations in Indonesia. This movement also uses

hashtags on social media with the hashtag

#MosiTidakPercaya. That means motion not believe

from people who had become the top Twitter trending

topic in Indonesia. The government and the DPR did

Protest social movements have also emerged

massively because of digitalization. This happened in

the Arab Spring phenomenon, which brought down

power in Egypt (Kubbara, 2019).

Digital-based aspirations and digital-based

protest social movements in political literature can be

categorized as a digital democracy phenomenon

(Nelson et.al, 2017). Ruby (2014) shows that digital

democracy also affects policies in Tunisia and Egypt.

The Arab Spring events in the two countries revealed

that the accessibility and rapid dissemination of

information through new social media have made it

easier to channel opinions and spread ideas (Coşkun,

2019). Thus, these events increase the ability of

citizens to influence government policies or political

elites. Freeman dan Quirke (2013) concluded that in

this digital democracy situation, there had been a big

leap for the government to consider the aspirations of

citizens in the decision-making process directly. In

addition, digital democracy is used by citizens as a

tool to pressure the government to make changes

(Rhue and Sundararajan, 2014). In Taiwan, political

Social Science in Action: A Study of the Paradox of Democracy in Civil Liberties in the Digital Era

235

forums conducted digitally are more visible in a

discursive manner by offering the possibility of

practicing deliberative democracy (Fen, 2010).

Although the practice of deliberative democracy has

not yet concluded that this phenomenon can be called

the digital public sphere, where the discourse process

on public issues occurs more deeply.

A number of studies above show that the digital

democratic era allows easy access to express

aspirations. The right to express opinions is more

easily channelled and responded to more quickly than

using conventional methods. This means that citizens'

civil liberties should be better in this digital era than

before entering the digital democracy era. Since civil

liberties are one of the indicators to assess a country's

democracy index, it is in this digital democracy era

that a country's democracy index should have

progressed (Miller and Vaccari, 2020). According to

The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) (2020),

Indonesia's democracy index score is 6.30, civil

liberties score is 5.59, and political culture score is

4.38. These scores have decreased since 2016.

Meanwhile, technological advances that continue to

develop should be able to encourage public

participation through digital democracy. Therefore,

democracy in Indonesia has regressed and is leading

to a worsening democracy. The decline in the

condition of democracy is a challenge for social

science in finding solutions that can improve digital

democracy in Indonesia. Therefore, this research

aims to analyse the actual phenomenon of democracy

in Indonesia, especially in the face of worsening civil

liberties in the era of digital democracy.

2 METHOD

This research was conducted using a qualitative

approach (Lune and Berg, 2017). In a qualitative

approach, discourse analysis was chosen by

researchers to reveal the phenomenon of digital

democracy in Indonesia. Discourse analysis is a

method to examine the discourse contained in

communication messages both textually and

contextually (Van Dijk, 1993). Thus, the analysis

used to connect the phenomenon with social criticism

related to digital democracy uses Critical Discourse

Analysis (CDA). In this research, the researcher uses

a qualitative approach with the Van Dijk (1993)

model of discourse analysis research. Therefore, this

study describes three dimensions: text, social

cognition, and social context. The unit of analysis

used is the internet user index from We Are Social

data and the democracy index from The EIU data.

The types of data collected are the results of research

and books related to digital democracy in Indonesia.

Analysis of text data in this study uses three stages

of Van Dijk; namely, the researcher collects texts

related to Civil Liberties, digital democracy, and

paradoxical democracy. Then describe and classify

the text according to the structure of the discourse

elements of Van Dijk model. Furthermore, an

explanation is carried out by analyzing the text

according to the technical analysis of the Van Dijk

model, which refers to six elements: thematic,

semantic, schematic, syntactic, stylistic, and

rhetorical. The data collection technique used in this

research is documentation. The documentary method

is data collection by tracing social cognition,

ideology, community situation, micro and macro

dimensions of society, socio-political actions, and

actors who have institutional roles. After that, analyze

the structure of society. In the macro-structure aspect,

we identified global meanings related to democracy

through themes in the Economist Intelligence Unit

Report. In addition, the researcher schemes the text in

digital media related to the #MosiTidakPercaya

hashtag. Thus, the meaning to be emphasised in this

research is the paradoxical democracy that exists in

Indonesia.

3 RESULT AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Result

Along with the development of information

technology and the high number of digital media

users, theoretically democracy in Indonesia should

increase from year to year. This is because the

presence of digital media and the advancement of

technology provides freedom for the public to control

the government openly. Coleman (2015) shows that

communication technologies are emerging at the right

time to address the challenges posed by the crisis of

confidence in democracy. This condition can be seen

from various cases in Indonesian digital media such

as the hashtag #MosiTidakPercaya (Motion of No

Confidence). In 2020, there was an Omnibus Law on

Job Creation that provoked reactions from various

groups of people in Indonesia. Public disappointment

emerged through social media Twitter (currently

changed to X). The sense of disappointment was

shown by giving the hashtag #MosiTidakPercaya. In

democratic principles, accountability and

transparency come first. However, the formation of

the omnibus law ignores the principle of

transparency, which is not in line with Law No.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

236

12/2011 on the formation of laws and regulations

(Khozen et.al, 2021). Thus, people are protesting

through social media. Optimism about digital

democracy is due to a more inclusive and effective

society. Therefore, this research provides an

overview of paradoxical democracy in Indonesia.

Paradoxical democracy leads to the democratic

principle of providing freedom of expression and

voting rights to balance individual freedom with the

collective need to maintain stability and justice.

When the internet first came into use, and cable TV

came into being, Shamberg (1971) argue that people's

skills in using information technology can restore

democracy. This happened in the United States fifty

years ago. Therefore, Shamberg believes that the

development of information technology is an

opportunity to make democracy better. Reflecting on

the current conditions in Indonesia, data on internet

users has continued to surge since 2013.

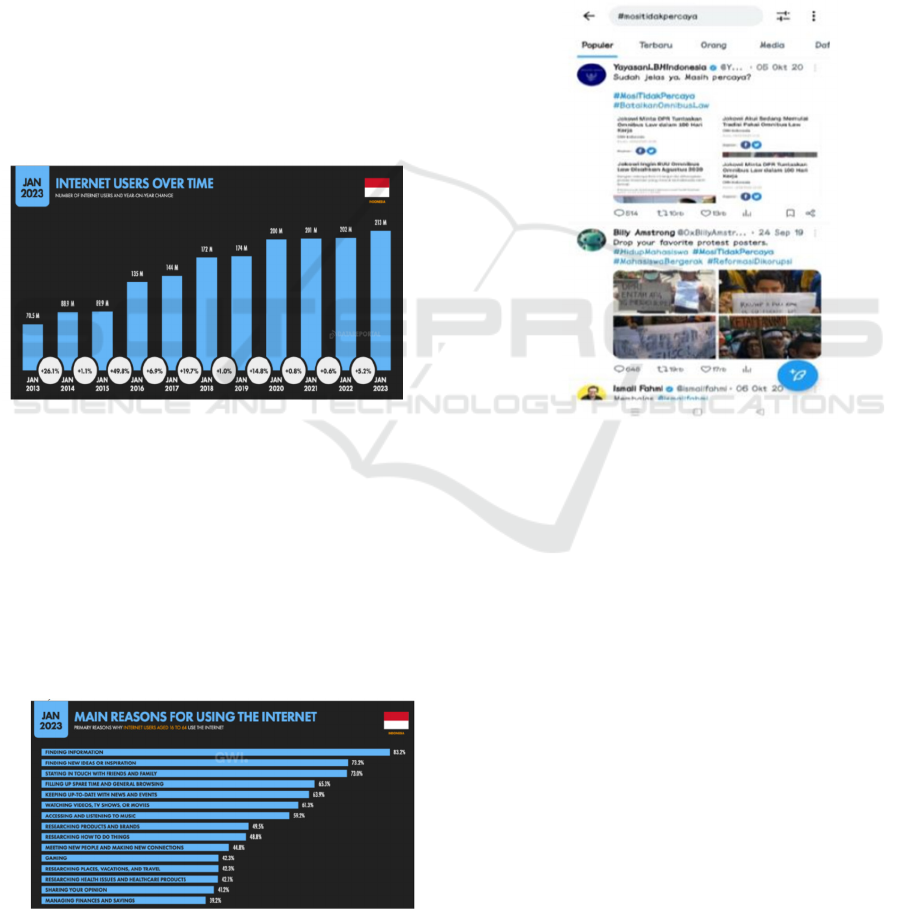

Figure 1: Internet users over time.

Source: We are Social (2023)

We are social is an agency that focuses on social

media. We are Social's Digital Indonesia 2023 report

provides an overview of social behaviour in online

communities, cultures and subcultures in Indonesia.

The data in Fig. 1 shows that in 2016 there was a

significant increase in internet users reaching 49.8%.

However, from 2020 to 2022 the increase in internet

users was not very significant. In 2023, there was a

5.2% increase in internet users.

Figure 2 : Main reasons for using the internet.

Source: We are Social (2023)

Fig.2 shows the various reasons for using the

internet in Indonesia. With regard to the conditions of

digital democracy, generally 83.2% of internet usage

is done to find information. However, 41.2% of

internet users share their opinions. In contrast, 31.1%

use social media to share and discuss their opinions.

Instagram is one of the social media platforms used

by internet users at 18.2%. Furthermore, Tiktok

(14.9%), Facebook (14.2%) and Twitter (8.2%).

Although twitter users are not as numerous as on

Instagram, but various layers of society use X or

twitter to show freedom of speech.

Figure 3 : Hashtag #MosiTidakPercaya.

Source: Twitter

Fig.3 reflects the challenges and dynamics of

democracy in the digital age. Therefore, the

democratic process has evolved into digital

democracy. In other words, digital democracy makes

information and communication technology support

the democratic process, increase public participation

and improve transparency in government. The

#MosiTidakPercaya hashtag is a form of public

scrutiny of government performance to improve

accountability. Unfortunately, the increasing number

of internet users has not had a significant impact on

Indonesia's democracy index.

Social Science in Action: A Study of the Paradox of Democracy in Civil Liberties in the Digital Era

237

Table 1 : Indonesia's democracy index 2020 - 2023.

YEAR 2020 2021 2022 2023

Overal

Score

6.30 6.71 6.71 6.53

Ran

k

64 52 54 56

Electoral

process and

p

luralism

7,92 7,92 7,92 7,92

Functioning of

Government

7,50 7,86 7,86 7,86

Political

Participation

6,11 7,22 7,22 7,22

Political

Culture

4,38 4,38 4,38 4,38

Civil Liberties 5,59 6,18 6,18 5,29

Source: The Economist Intelligence Unit (2024)

Based on the Democracy Index Report from The

Economist Intelligence Unit (2024), the democracy

index in Indonesia has decreased in score and rank.

Table 1 shows that the civil liberties index value

increased in 2021 and stabilised in 2022. However, in

2023, the civil liberties index decreased by 0.89%.

Civil liberties are basic rights that must be protected

by law as a form of individual protection from abuse

of power by the state. In addition, from 2014 to 2023,

Indonesia's democracy index has always experienced

an increase and decrease. The Economist Intelligence

Unit (2024) in its report indicates that democracy in

Indonesia is flawed.

3.2 Discussions

The phenomenon of increasing social media users

logically and based on a number of studies that have

been presented allows civil liberties, for example in

terms of expressing opinions and associating, to

increase which has an impact on the high number of

Indonesia's democracy index. But in fact, amidst the

increasing number of internet users and social media

users, Indonesia's civil liberties rate is low. This

condition is supported by the researcher's findings

through discourse analysis of #MosiTidakPercaya on

social media regarding the enactment of the Omnibus

Law. This research is in line with Mahy (2022)

Whereas, there has been a decline in democracy in

Indonesia. One of these setbacks is shown through the

amendments made to the enactment of the omnibus

law. Thus, the 2023 democracy index data issued by

The Economist Intelligence Unit is in line with

current conditions. The existence of discourse

through social media does not have a significant

impact. Theoretically, when entering the digital era,

few scientists believe that the presence of new

communication technology will bring better

democracy (Coleman, 2015) (Halbert, 2016).

Without a doubt, digital communication has emerged

at the right time to answer the challenges that arise

due to the crisis of trust in democracy[33]. However,

the existing technology in Indonesia has not been able

to increase the index of a good democracy. Therefore,

the democracy index presented by Halbert (2016) and

Coleman (2015) does not show significance. This is

because, empirically based on reports from research

institutes and previous studies, democracy in

Indonesia has worsened in the last four years.

As revealed in the research findings, it concludes

that democracy in Indonesia leads to an illegal

situation (an increasingly illiberal situation). These

findings are in line with the study results by Diprose

et al. (2019). In addition, the research of Kusman and

Istiqomah (2021) positioned Indonesia in the new

despotism political situation, which refers to the

theoretical terminology put forward by Keane (2020).

Diprose et al. (2019) also added that the illiberal

tendency is growing, however, alongside economic

and resource nationalism agendas. Nevertheless, the

"illiberal turn" has been driven by the deepening

inequalities in Indonesian society. Thus, this study

shows a strong trend towards the growth of an illegal

situation in Indonesia. Factors that drive the illegal

conditions include the increasing inequality in

society, especially in terms of civil liberties and other

democratic rights. It is not surprising that democratic

freedom in Indonesia appears to be shackled by

political dynasties and oligarchs. Hadiz (2017), in his

research, also adds that the failure factor of the state

and market in dealing with social injustice is the

factor being analyzed. Therefore, the results of this

study indicate that the declining democracy index is a

factor that encourages the emergence of illegal

practices.

The research findings reveal that during the last

14 years, there has been an increase and decrease in

the Indonesian democracy index. In addition, civil

liberties and political culture are not considered to be

in good condition. Thus, it is undeniable that the

decline in the democracy index reveals the

phenomenon of illegality and new despotism in

Indonesia. The worsening of civil liberties occurs

when digital social media is growing in Indonesia. In

addition, the increasing increase in social media users

does not indicate an increase in the democracy index.

This is possible because of the discovery of new

theoretical problems from the practice of digital

democracy in the case of Indonesia.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

238

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study concludes that the theory of digital

democracy believes that the development of

information technology allows the wider public

involvement in conveying aspirations and criticisms

of the government; in fact, in the case of Indonesia, it

is the opposite. This is because Indonesia's

democracy index fell 0.18 compared to the previous

year. Therefore, there is a phenomenon in Indonesia

that shows that digital democracy cannot encourage

better democracy and increase civil liberties in a

country. The results of this study are expected to be a

concern for the government to formulate digital

democratic governance. Because if the government is

not ready to enter the era of digital democracy where

criticism occurs very quickly and it is easy to become

a public conversation on social media. This will lead

to new conflicts and reduce the people's civil liberties.

In addition, this research is expected to be a guide for

future research related to new digital-based political

behavior. Considering the condition of civil liberties

has always been a problem when expressing their

aspirations. Especially with the Electronic

Information and Transaction Law which can be used

to reduce civil liberties through digital democracy.

Therefore, it takes wisdom in the use of social media.

Thus, an increase in the number of internet users can

boost the democracy index in Indonesia

REFERENCES

A. K. Kusman and M. Istiqomah, “Indonesia’s ‘new

despotism,’” Melb. Asia Rev., vol. 5, pp. 1– 8, 2021,

doi: 10.37839/mar2652-550x5.13.

B. L. Lune, H. & Berg, Qualitative Research Methods for

the Social Sciences (9th Edition). 2017.

C. Fen Pai, “Deliberative Democracy via Cyberspace: A

Study of Online Political Forum @Taiwan,” Cardiff

University, 2010.

C. Judhita, “Interaksi Komunikasi Hoax di Media Sosial

serta Antisipasinya Hoax Communication Interactivity

in Social Media and Anticipation,” J. Pekommas, vol.

3, no. 1, pp. 31–44, 1925, [Online]. Available:

https://www.neliti.com/publications/261723/hoax-

communication-interactivity-in-social-media-and-

anticipation-interaksi-komu

C. Ruby, “Social Media And Democratic Revolution: The

Impact of tNew Forms of Communication Democracy,”

Cuny City College, 2014.

D. Curran, “Risk, innovation, and democracy in the digital

economy,” Eur. J. Soc. Theory, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 207–

226, 2018, doi: 10.1177/1368431017710907.

D. Halbert, “Intellectual property theft and national

security: Agendas and assumptions,” Inf. Soc., vol. 32,

no. 4, pp. 256–268, 2016, doi:

10.1080/01972243.2016.1177762.

E. R. Coşkun, “The role of emotions during the Arab Spring

in Tunisia and Egypt in light of repertoires,”

Globalizations, vol. 16, no. 7, pp. 1198–1214, 2019,

doi: 10.1080/14747731.2019.1578017.

H. Kermani, “#MahsaAmini: Iranian Twitter Activism in

Times of Computational Propaganda,” Soc. Mov. Stud.,

pp. 1–11, 2023, doi: 10.1080/14742837.2023.2180354.

I. Khozen, P. B. Saptono, and M. S. Ningsih, “Questioning

Open Government Principle within the Law-Making

Process of Omnibus Law in Indonesia Article Info,” J.

Soc. Sci. Humanit., vol. 11, no. 2, p. 2021, 2021.

J. A. G. M. van Dijk, “Digital Democracy: Vision and

Reality,” in Public Administration in The Information

Age: Revisited, I. Snellen, M. Thaens, and W. van the

Donk, Eds., Netherlands: IOS Press, 2012, p. 63.

J. Freeman and S. Quirke, “Understanding E-Democracy

Government-Led Initiatives for Democratic Reform,”

JeDEM - eJournal eDemocracy Open Gov., vol. 5, no.

2, pp. 141–154, 2013, doi: 10.29379/jedem.v5i2.221.

J. Keane, The New Despotism. Massachusetts: Harvard

University Press, 2020.

J. L. Nelson, D. A. Lewis, and R. Lei, “Digital Democracy

in America: A Look at Civic Engagement in an Internet

Age,” Journal. Mass Commun. Q., vol. 94, no. 1, pp.

318–334, 2017, doi: 10.1177/1077699016681969.

L. Rhue and A. Sundararajan, “Digital access, political

networks and the diffusion of democracy,” Soc.

Networks, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 40–53, 2014, doi:

10.1016/j.socnet.2012.06.007.

L. Zhang and A. Fung, “The myth of ‘shanzhai’ culture and

the paradox of digital democracy in China,” Inter-Asia

Cult. Stud., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 401–416, 2013, doi:

10.1080/14649373.2013.801608.

M. Hilbert, “The maturing concept of E-democracy: From

E-voting and online consultations to democratic value

out of jumbled online chatter,” J. Inf. Technol. Polit.,

vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 87– 110, 2009, doi:

10.1080/19331680802715242.

M. L. Miller and C. Vaccari, “Digital Threats to

Democracy: Comparative Lessons and Possible

Remedies,”

Int. J. Press., vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 333–356,

2020, doi: 10.1177/1940161220922323.

M. Lim, “Many Clicks but Little Sticks: Social Media

Activism in Indonesia,” J. Contemp. Asia, vol. 43, no.

4, pp. 636–657, 2013, doi:

10.1080/00472336.2013.769386.

M. Shamberg, Guerrilla television. New York: Henry Holt

& Co., 1971.

N. M. A. Majid, “Digital Democracy in Malaysia: Towards

Enhancing Citizen Participation,” University of

Melbourne Australia, 2010.

O. A. Kubbara, “International actors of democracy

assistance in Egypt post 2011: German political

foundations,” Rev. Econ. Polit. Sci., vol. ahead-of-p,

no. ahead-of-print, 2019, doi: 10.1108/reps-04-2019-

0043.

P. M. Lutscher and N. Ketchley, “Online repression and

tactical evasion: evidence from the 2020 Day of Anger

Social Science in Action: A Study of the Paradox of Democracy in Civil Liberties in the Digital Era

239

protests in Egypt,” Democratization, vol. 30, no. 2, pp.

325–345, 2023, doi: 10.1080/13510347.2022.2140798.

P. Mahy, “Indonesia’s Omnibus Law on Job Creation:

Legal Hierarchy and Responses to Judicial Review in

the Labour Cluster of Amendments,” Asian J. Comp.

Law, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 51–75, 2022, doi:

10.1017/asjcl.2022.7.

P. Nyoka and M. Tembo, “Dimensions of democracy and

digital political activism on Hopewell Chin’ono and

Jacob Ngarivhume Twitter accounts towards the July

31st demonstrations in Zimbabwe,” Cogent Soc. Sci.,

vol. 8, no. 1, 2022, doi:

10.1080/23311886.2021.2024350.

R. Anggraeni and C. I. L. Rachman, “Omnibus Law in

Indonesia: Is That the Right Strategy?,” in International

Conference on Law, Economics and Health (ICLEH

2020), 2020, pp. 180–182. doi:

10.2991/aebmr.k.200513.038.

R. Diprose, D. McRae, and V. R. Hadiz, “Two Decades of

Reformasi in Indonesia: Its Illiberal Turn,” J. Contemp.

Asia, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 691–712, 2019, doi:

10.1080/00472336.2019.163792

R. Levy, “Social Media, News Consumption, and

Polarization: Evidence from a Field Experiment,” Am.

Econ. Rev., vol. 111, no. 3, pp. 831–870, 2021, doi:

10.1257/AER.20191777.

S. Coleman, “Digital Democracy,” in The International

Encyclopedia of Political Communication, G.

Mazzoleni, K. G. Barnhurst, K. Ikeda, R. C. M. Maia,

and H. Wessler, Eds., New York: John Wiley & Sons,

Inc., 2015.

T. Van Dijk, “Principals of Discourse Analysis,” Discourse

Soc., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 249–283, 1993.

The Economist Intellegence Unit, “Democracy Index 2020

: In Sickness and in Health.” Accessed: Feb. 10, 2021.

[Online]. Available:

https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-

2020/

The Economist Intelligence Unit, “Democracy Index 2023:

Age Of Conflict,” 2024. [Online]. Available:

www.eiu.com.

V. R. Hadiz, “Indonesia’s year of democratic setbacks:

towards a new phase of deepening illiberalism?,” Bull.

Indones. Econ. Stud., vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 261–278, 2017,

doi: 10.1080/00074918.2017.1410311.

We Are Social, “Digital 2023 Indonesia,” 2023. [Online].

Available: https://wearesocial.com/wp-

content/uploads/2023/03/Digital-2023-Indonesia.pdf

Y. C. Kim and J. W. Kim, “South Korean Democracy in the

Digital Age: The Candelight Protests and the Internet,”

Korea Obs., vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 53–83, 2009.

Y. S. Tseng, “Rethinking gamified democracy as frictional:

a comparative examination of the Decide Madrid and

vTaiwan platforms,” Soc. Cult. Geogr., vol. 24, no. 8,

pp. 1324–1341, 2023, doi:

10.1080/14649365.2022.2055779.

Y. Takao, “Democratic Renewal by ‘Digital’ Local

Government in Japan,” Pac. Aff., vol. 77, no. 2, pp.

237–262, 2004.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

240