Reconceptualizing Empirical Data: Developing Higher Order

Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning

Asep Suryana

a

Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Competence, Reconceptualization of Empirical Data, Undergraduate Level, Higher Order Thinking.

Abstract: The competence of reconceptualizing empirical data tends to be neglected in the qualitative research learning

system in Sociology Study Programs in Indonesia, especially at the undergraduate level. The author argues

that there are several academic tools that have been pioneered by experts and can be developed into a toolbox

for the competence of reconceptualizing empirical data. However, because the competency of

reconceptualizing empirical data is a high-level reasoning skill, the target competency of reconceptualizing

empirical data is framed so that it can formulate empirical novelty, not theoretical novelty. With the

framework of formulating empirical novelty, the competence of reconceptualizing empirical data requires

undergraduate researchers to be able to thematization and write down their field findings at a more abstract-

conceptual level. For this, sociology students should be skilled at the coding, using the tashawur approach,

and using more theoretical concepts to develop concepts at a more intermediate and grounded level—while

being framed by public issues and current literature as much as the undergraduate student can.

1 INTRODUCTION

Qualitative research skills for sociology graduates are

central. Research competencies for sociology

graduates are the same as drawing skills for

architecture students, or language skills for foreign

language scholars. Therefore, this research skill is

also the main competency of the profile of sociology

graduates (Ferguson & Sweet, 2023; Pike et.al.,

2017), as well as useful as a provision for them to be

ready to enter the job careers (Mekolichick, 2022;

Tambunan and Budiman, 2022).

Overall, the body of knowledge for learning

qualitative research is composed of three patterns.

The first is how to design qualitative research (Flick

[editor], 2022); second, how to collect data (Flick

[editor], 2014); and finally, how to skillfully analyze

data (Flick [editor], 2018). These include

generalization (Maxwell and Chmiel, 2014), coding

(Thornberg and Charmaz, 2014), and theorization

(Kelle, 2014). However, their discussions are aimed

at professional academic researchers, not

undergraduate students. Therefore, the various

terminologies and ideas that surround them must be

adapted to the needs, abilities and learning targets of

undergraduates (Mekolichick, 2022; Tambunan and

Budiman, 2022).

The author argues that the learning outcome of

research at the undergraduate level of sociology is to

formulate empirical novelty—not theoretical novelty.

Theoretical novelty is for PhD level. The empirical

novelty learning outcome is in accordance with the

target of undergraduate education (especially

undergraduate sociology) (Mekolichick, 2022;

Tambunan and Budiman, 2022). In that regard, it is

important to point out that the sociology

undergraduate learning design is patterned after the

vocationalization of sociology. That is, a combination

of the category of policy sociology and the category

of public sociology in the sense of Buraway (2005),

as well as he is directed to have technical skills and

soft skills as preparation for them to enter the enter

the job careers. Even more technically, what is

formulated as reconceptualization of empirical

data—borrowing the typology of data theorization

from Kelle (2014)—is to use more theoretical

concepts to develop derivative concepts at a more

intermediate level and grounded.

The ability to reconceptualize the empirical data

becomes important when we consider strong

complaints about the lack of learning of this

competency in sociology study programs, especially

at the undergraduate level. Swedberg (2012, 2016,

2017), for example, complains about that. The

594

Suryana, A.

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data:Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0013410600004654

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science (ICHELS 2024), pages 594-606

ISBN: 978-989-758-752-8

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

capacity to theorize and conceptualize various great

figures of sociology (such as Bourdieu) ms to be

obtained naturally, not because of formal education

in college.

The neglect of learning on the competence of

reconceptualizing empirical data also occurs in

Indonesian universities. If we look at the syllabus of

lectures and textbooks of qualitative research in

Indonesian at the undergraduate level, the ability to

reconceptualize empirical data is not considered

important. The discussion of lecture syllabi and

textbooks of qualitative methods in Indonesian tends

to focus on ontological aspects (what to look for in

qualitative research) and how data collection

techniques—and is always contrasted with

quantitative research (Moleong, 2019; Mulyana,

2010).

To discuss the empirical data reconceptualization

competency argument, this article is divided into five

sections. The first part is to place the competence of

reconceptualizing empirical data in the realm of data

analysis and at the level of higher order thinking. The

reconceptualization goal is to formulate empirical

novelty at a more intermediate level. The second part

is a description of the research method that

emphasizes literature study. There are various types

of literature tracked in this article. The third and

fourth sections discuss the body of knowledge of

reconceptualizing empirical data and learning

outcomes of undergraduate qualitative research. The

last section discusses various academic tools that can

be used to develop competence in reconceptualizing

empirical data.

2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This article uses the learning outcomes approach. As

a pedagogical strategy that places students at the

center of learning, the learning outcome approach

aims to build specific competencies (both at the level

of technical skills and soft skills) that students have

after taking a course (Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et.al.

(editors), 2018; Arnold et.al. (editors), 2020). In this

context, the learning outcome of data

reconceptualization competency is being able to

construct and formulate empirical research findings.

The competency of reconceptualizing empirical

data is a technical academic skill that undergraduate

students should have, albeit in a basic level form. It is

a sub-competency of the qualitative researcher

competency. Of course, there is a limit to the

achievement of empirical data reconceptualization

competencies when taught at the undergraduate level.

From the author's experience teaching in the

Sociology Study Program for 27 years (1997-2024)

(Suryana, 2012), the target competency of

reconceptualizing empirical data is for undergraduate

students to be able to formulate empirical novelty, not

theoretical novelty. The target of theoretical novelty

is not realistically taught at the undergraduate level

because it is the main competency of the doctoral

level.

Empirical novelty means that undergraduate

researchers can thematization and write down their

field findings at a more abstract-conceptual level. Of

course, the conceptualization process is guided by the

underlying central theory/concept—while being

framed by public issues and current literature to the

best of the student's ability (Orange, 2023; Dodgson,

2019). At the same time, in order to reconceptualize

empirical data, undergraduate students must also be

able to record and reconstruct data (write fieldnotes,

write diaries, and write memos), and be able to

analyze data (open coding of fieldnotes, visualization

of initial field findings, thematization of field

findings, design of chapters and subchapters, writing

reports, and linking empirical data findings with

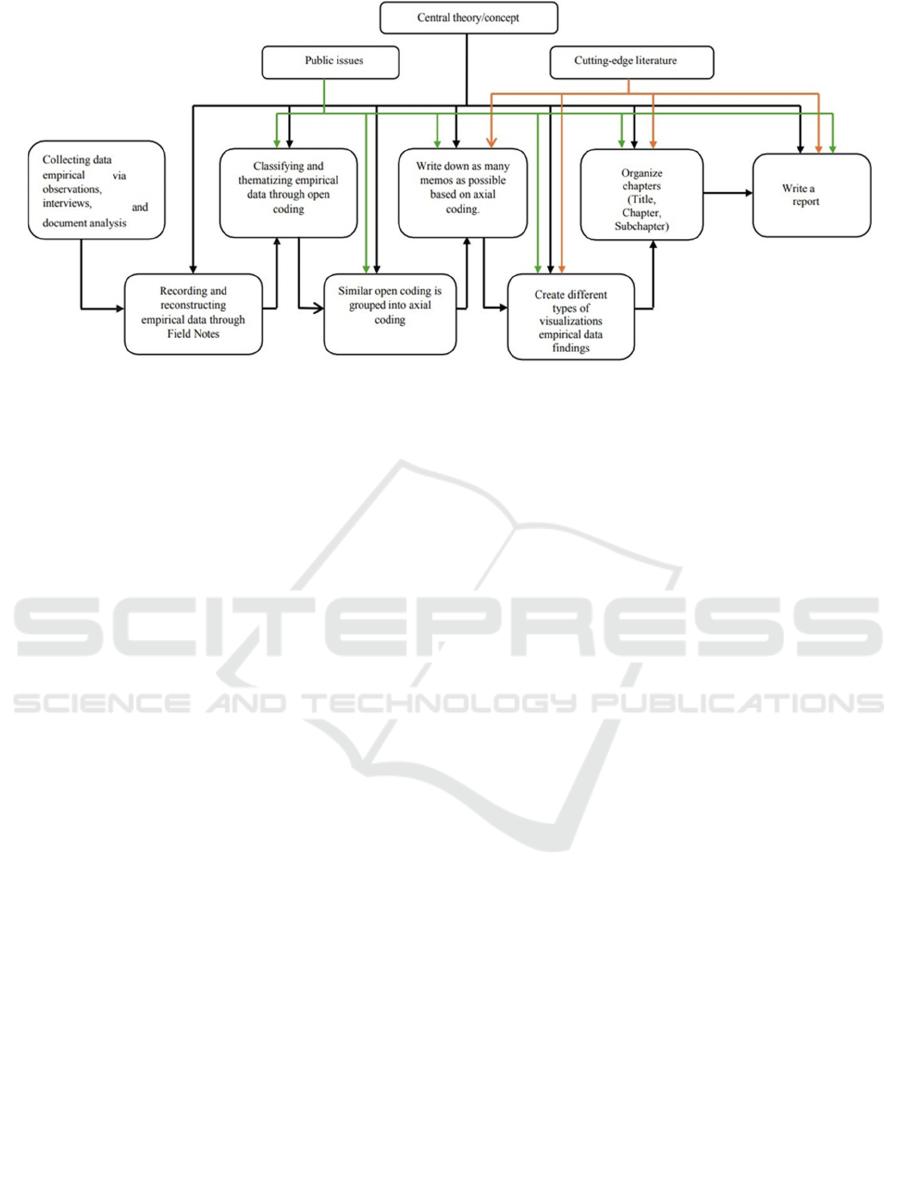

related literature) (Figure 1).

On the other hand, as a pedagogical strategy, the

learning outcomes approach is also related to the

body of knowledge in the field of science being

taught. If the body of knowledge contains a map of

information, concepts, theories or rules in a field of

science, learning outcomes are more specific.

Learning outcomes aim to define the

various

elements of the field's body of knowledge that

students must master (Miles & Wilson, 2004). Body

of knowledge provides raw material for formulating

learning outcomes. Meanwhile, learning outcomes

are formulated from the concepts, rules, and

competencies in the body of knowledge.

In other words, the body of knowledge is the

foundation for the formulation of learning outcomes.

The formulation of learning outcomes should be

based on the structure and content of the body of

knowledge of a field of study (Thorn & Sydenham,

2008). A good body of knowledge can serve as a

guide, foundation and reference for which parts of the

body of knowledge are important to be mastered by

learners and formulated as learning outcomes.

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data:Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning

595

Figure 1: Body of Knowledge Reconceptualizing Empirical Data.

So, not everything in the body of knowledge is

learned. Learning outcomes emphasize, limit, and

direct only the relevant and urgent parts of the body

of knowledge to be learned. Furthermore, learning

outcomes that are well formulated will help learners

connect the knowledge they gain with real situations

in everyday life.

3 RESEARCH METHODS

As research categorized as teaching and learning in

Sociology, this article takes three methodical steps to

collect and compile empirical data

reconceptualization competencies.

First, this research explores five types of literature

to identify various academic techniques and tools that

have previously been pioneered by experts, to

formulate them as academic tools to build

competence in reconceptualizing empirical data.

(1) Teaching and learning in sociology literature,

especially those related to qualitative research

learning strategies such as Medley-Rath (2023); as

well as those related to building critical reasoning

skills in sociology (Kane & Otto, 2017; Kane, 2023).

(2) The qualitative methodology literature itself as

indicated by Babbie 2021; Cresswell (2016),

Newman 2014), Mills & Hubermans (2014), and

Morse (2006). (3) The theorized competence

literature of Swedberg (2012, 2016, 2017) and Kelle

(2014). (4) Literature of Mantiq (Islamic Logic)

textbooks, especially related to the tashawur

(conception) approach (Sambas, 1996 [2017]: 46-68;

Muminin, 2022; Al-Abhari, 2022; Nuruddin, 2020;

Hurley & Watson, 2018; Hayon, 2000). (5)

Teaching and learning social research methods

literature (Nind [editor], 2023).

Second, this research attempts to build on the

academic tools previously pioneered by Swedberg

(2017, 2016, 2012). Following Swedberg (2017,

2016, 2012), this research argues that the competence

of reconceptualizing empirical data is carried out in

two stages: (a) the context of justification and (b) the

context of discovery. The context of justification is to

describe how theory is practiced in research. Whereas

the context of discovery is where relevant academic

tools are used to gain insights, and then the theory

used in the context of justification stage is further

developed (Burawoy, 2009).

The various academic tools extracted from the five

types of literature are grouped into two stages or ideal

types—following the stages of Swedberg (2017, 2016,

2012)—namely (a) the context of justification and (b)

the context of discovery. The author argues that the

various academic tools of qualitative research learning

strategies obtained from the repertoire of teaching and

learning in sociology and qualitative methodology

literature are in the context of justification. These

academic tools are the skills of collecting and

processing, visualizing data along with how the

conceptual framework used can function as a frame

and guide for collecting, processing, and visualizing

empirical data.

Meanwhile, the theorized academic tools of

Swedberg (2012, 2016, 2017) and Kelle (2014), the

higher-level thinking and critical sociological

thinking competencies of Kane & Otto (2017) (Kane

2023), and various academic tools from Mantiq (such

as tashawur, division, classification, and predicable)

can be formulated as an academic toolbox for the

discovery context.

In this regard, the author tries to operationalize (a)

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

596

the context of justification and (b) the context of

discovery as formulated by Suryana (2020).

Following Swedberg's (2017, 2016, 2012), the

process of reconceptualizing empirical data begins

with the identification of insights, because they are

not covered by the main theory or auxiliary theory

used (Buroway, 2009). The insights are then further

developed, to provide a contribution of elements of

conceptual for the development of the theoretical

approach used (Suryana, 2020).

The third step is to reflect on the stages of learning

Qualitative Research Practices (PPK) that have been

held by the Sociology Study Program and the

Sociology Education Study Program at the

Universitas Negeri Jakarta for 18 years, from 2006 to

2024. It should be stated that the Sociology Study

Program and the Sociology Education Study Program

have organized Qualitative Research Practices in a

guided manner since 2006, which is a continuation of

the Qualitative Research Methods course. If the

theoretical aspects are taught in the Qualitative

Research Methods course, the practical aspects are

carried out in Qualitative Research Practice. Of

course, during the 18 years of learning Qualitative

Research Practice, various learning instruments have

been innovated and institutionalized, and some of the

learning outcomes of Qualitative Research Practice

have been recorded by Suryana (2012).

This research tries to complement Suryana's

(2012) article, especially in terms of data

reconceptualization competence. The focus of this

research is on the learning stages that allow data

reconceptualization competencies in Qualitative

Research Practice to be honed and built. The focus

of data collection is on the phases of writing

fieldnotes, visualizing field findings, writing memos,

thematizing findings, drafting chapters and

subchapters, writing reports, and linking empirical

data findings with related literature. The learning

stages of Qualitative Research Practice that have been

institutionalized for 18 years (2006-2024) can be used

as a source of field data, as well as a reference for

reflection to build the competence of

reconceptualizing the empirical data that is the focus

of this research.

3.1 Body of Knowledge

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data

Where is the position of data reconceptualization

competency in the body of knowledge of qualitative

research. Following Flick's categorization (2014, 2018,

and 2022), the competency of reconceptualizing

empirical data is in the realm of data analysis. There

are two directions of data reconceptualization, namely

from the angle of warrant, and the angle of the

relationship between the theory/concept and the

empirical data itself (Babbie, 2021: 29-59). Figure 1

shows three guidelines for competence in

reconceptualizing data from the warrant angle. The

suffix [re] in conceptualization indicates these three

things. They are the central theory or concept used, the

public issue framing it, and the state of the art of the

recent literature examine.

Meanwhile, in terms of the relationship between

theory/concept and empirical data, the

reconceptualization of empirical data is developed

from Kelle's (2014) three typologies of data

theorization. The first typology is (1) using more

theoretical concepts to develop concepts at a more

intermediate level. (2) Putting qualitative data as

material to revise more theoretical concepts. Finally

(3) is to transfer the intermediate concepts to a new

research domain. For the understanding of

reconceptualizing empirical data at the undergraduate

level of sociology, it refers to the first typology. That

is, using more theoretical concepts to develop

concepts at a more intermediate level and grounded

(Babbie, 2021).

Figure 1 shows the body of knowledge for

reconceptualizing empirical data as a set of technical

skills for qualitative research academics. It starts with

the skill of collecting and recording empirical data to

writing a report. The first step in reconceptualizing is

to be able to write fieldnotes and memos.

Fieldnote (FN) is (a) a medium for recording field

data, as well as (b) a material for processing data at an

advanced stage. As a field data recording medium, the

FN contains emic data (in the form of ideas, issues,

sentences, etc. from informants), what was observed,

and what was heard. Meanwhile, as material for

processing data at an advanced stage, FN also contains

the researcher's comments or (ethical) analysis; and (ii)

the grouping, classification and categorization of data

through open coding.

The memo writing is done after writing the FN.

Writing memos is done after several open codes have

been grouped into axial codes. Memo is a detailed

description of axial coding. After the axial-coding is

found, to detail or illustrate the axial-coding, a memo

is written.

So, a memo is a conceptualization of data. It does

not simply report data. A memo (1) must be able to tie

together disparate pieces of data and formulate them

into a unified group. It can also contain (2) fragments

of data that are assembled as examples, illustrations, or

evidence of more abstract concepts. Memos are titled

(with the key concept discussed). Similar memos are

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data:Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning

597

filed under the same theme or umbrella concept; and

separated from the data archive. Thus, memos should

contain the results of axial coding and have moved in

a more conceptual direction.

Composing FNs and memos requires technical

writing skills. For FNs, it requires descriptive and

narrative writing skills. As for composing memos, it

requires higher technical skills—in Marahimin's

(2000) terminology—referred to as expository

writing techniques.

Writing a description is describing an object,

place, atmosphere, or situation with words in a lively

and captivating manner. Through his writing, the

reader .ms to be able to. what the author’s, "taste"

what the author eats, "feel" what he feels, and

"conclude" what the author concludes (Marahimin,

2000). The content of descriptive writing is the result

of what is observed, what is heard, and what is felt

through all five senses that the author has in a certain

place and time.

Narrative is writing down the events or characters

that are being told. Narrative writing has a plot (a story

that has a flow) and has a focus, claim, angle,

argument, controlling idea, or thesis. Marahimin

(2000) mentions other characteristics of narrative

writing. Among them are (1) plot: events, characters,

and conflicts; (2) setting (time setting, place setting,

economic setting, cultural setting, political setting,

government setting, social setting) or local setting. (3)

Point of view, writing angle, or narrator's position (I-

ness; or he-ness). (4) Dialogue, and (4) narrative

pattern (flashback style; beginning-middle-end).

Meanwhile, expository writing techniques are very

helpful for writing memos. Expository writing is

writing that contains proof of a thesis, claim, or

controlling idea. In memos, the thesis that the writer

wants to put forward is embodied in the title. The

whole description is about proving that the title is true.

3.2 Qualitative Research Learning

Outcomes for Undergraduate

Program

This article argues that the target competency of

reconceptualizing empirical data is for undergraduate

students to formulate empirical novelty, not

theoretical novelty. The target of theoretical novelty

is not realistic to be taught at the undergraduate level

because it is the main competency of the doctoral

level. In that context, the competency of

reconceptualizing empirical data of qualitative

research is based on two things. First, (1) students'

ability to categorize and systematize their empirical

data to a more abstract-conceptual level, and (2) their

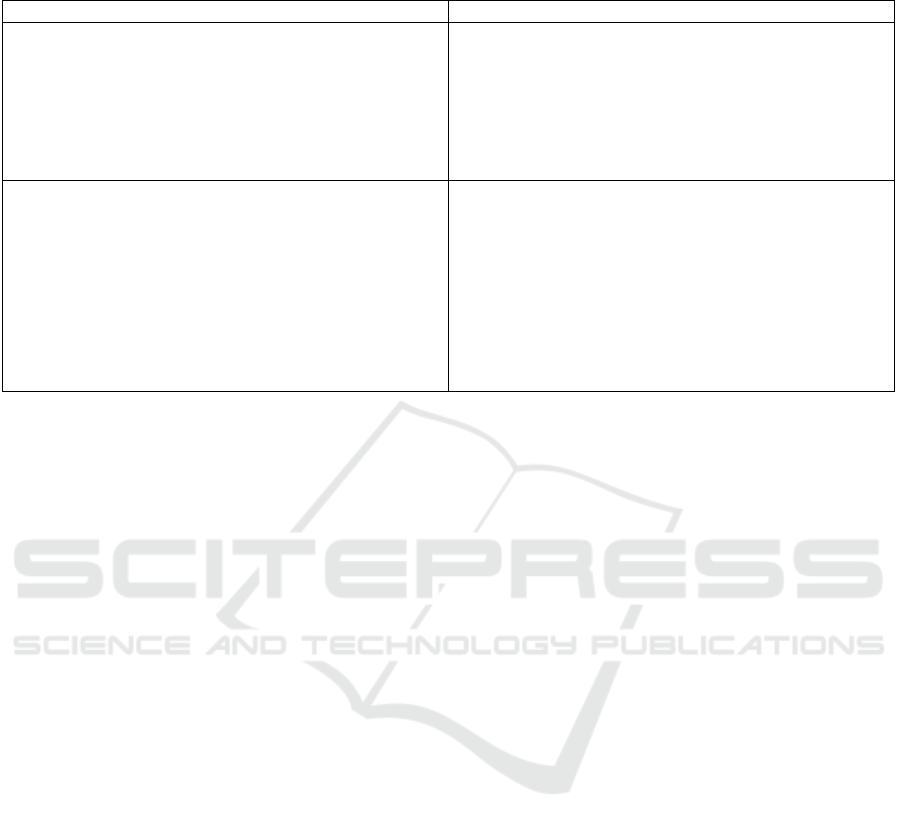

ability to draft chapters and subchapters (Table 1, and

Figure 1).

In order for the first competency to be achieved,

there are three supporting skills that must be mastered

by prospective sociology graduates. The three are (a)

being able to record and reconstruct data (writing

fieldnotes, writing diaries, and writing memos); (b)

being able to perform three stages of coding (open

coding on fieldnotes, axial coding, and selective

coding); and (c) being able to visualize research

findings (tables, matrices, flowcharts, concept

mapping) (Newman, 2014; Hubermans and Marshal,

2014; Thornberg and Charmaz, 2014).

Meanwhile, the competency of organizing the

chapter design is divided into three sub competencies

(Table 1). In order to be able to write relevant

headings or terminology, students are trained to be

able to tie the description with a title that has the

characteristics of: (a) describes what is in the content

of the description, (b) is interesting (eye catching), (c)

readers feel the need to read, (d) contains a maximum

of 12 words, and (e) is written in the form of phrases,

not sentences. The title should not only be conceptual

but should be written in the form of a concept that

already has a variety of values or “variables”.

On the other hand, the skill of composing the title

should reflect specific keywords or terminology that

are guided and based on the central theories/concepts

used. Students must also be able to dialectic their

conceptual guidance with the empirical data findings

(Wagner, 2009). The results of the dialectic are then

categorized, thematized, and visualized by framing

them on their theoretical foundation (Morse, 2006;

Kane & Otto, 2017). In fact, the dialectic is already in

the category of synthesis, because it tries to interrelate

the theoretical foundations he has with the tendencies

and reasoning of the empirical data he encounters

(Dodgson, 2019). This process is a more advanced

stage of higher order thinking.

The above synthesis process is also rooted in the

sociological research tradition itself. The research

methods literature in sociology often emphasizes that

the categorization, thematization and visualization of

research findings should be consistent with the

paradigmatic position of sociology that the researcher

takes (Marvasti 2004; Wagnera, Garner and

Kawulichc, 2011). Indeed, as a multi-paradigmatic

science (Ritzer 1975; Purdue 1986), the discipline of

sociology demands that qualitative research

conducted by a researcher must be in line with the key

ideas of the overarching sociological paradigm

(Babbie 2021). Reconceptualization of empirical data

must also be guided and in line with the overarching

sociological paradigm.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

598

Table 1: Learning Outcomes of Competency in Reconceptualizing Empirical Data for Undergraduate Programs.

Sub-Competencies Sub-Competency Elements

(1) Undergraduate students can classify, categorize,

and thematize empirical data to a more abstract

conceptual level.

(1) Can record and reconstruct data (writing

fieldnotes, diary writing, and memo writing)

(2) Can perform three stages of coding (open

coding on fieldnotes, axial coding, and selective

coding)

(3) Can visualize research findings (tables,

matrices, flowcharts, concept mapping)

(2) Be able to draft the organization of chapters and

subchapters

(1) Write down relevant headings or terminology

(2) The keywords and terminology are guided and

based on the central theories/concepts used.

(3) The chapters and subchapters are framed and

guided by:

(a) the public issues surrounding it.

(b) the latest literature to the best of the

undergraduate student's ability.

(c) the reasoning of the approach/theory/concept

used.

The key words and derivative terminology above

reflect how theory is used and operationalized

(deductively) for a particular topic, research subject

and research location. Using Kelle's (2014) typology

of theorizing, this higher stage of reasoning is using

more theoretical concepts to develop concepts at a

more intermediate and grounded level. At this stage,

inductive reasoning is more dominant. The more

abstract theoretical concepts are only placed as

framing. The deductively derived key terms serve as

a frame: so that the process of coding, inductive

reasoning, or conceptualization can be carried out.

From that angle, the prospective sociology scholar

should be able to transfer and operationalize the

concepts he uses to the topic and location of his

research. And at the same time, the formulation of

derivative terms is also to place qualitative data as

material for revising and modifying these more

theoretical concepts (Kelle, 2014).

The headings and subheadings are then organized

into a chapter and subchapter layout. It is like the

table of contents in a book. The chapters should

reflect the reasoning framed by the theory used. It

should also reflect the author's response to current

public issues and literature to the best of the

undergraduate student's ability.

In this regard, various writing development

techniques found in textbooks can be referred to.

Choesin (2016) and Bailey (2003, 2018), for

example, have shown how a piece of writing is

developed. Some are chronological, flashback,

effect-to-cause, per-aspect, and others. The pattern of

writing development as proposed by Choesin (2016)

and Bailey (2003, 2018) can be referred to and

developed for writing report chapters. Students can

combine two or even three flows for the writing

division.

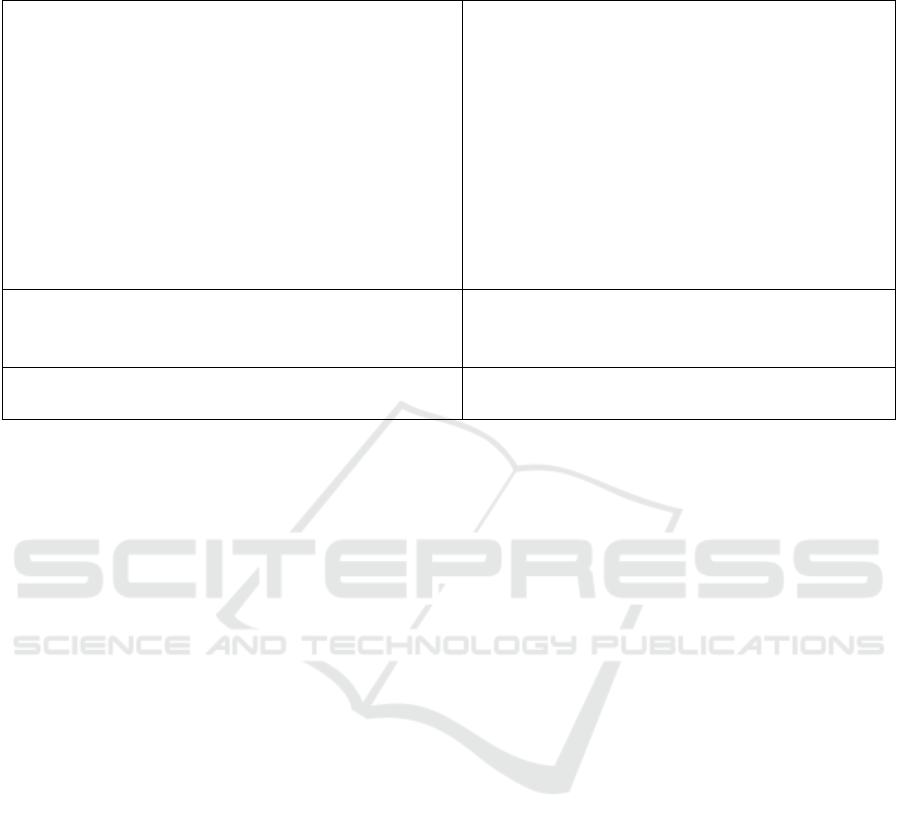

However, the reconceptualization competencies

in Table 1 must be based on more general

competencies that qualitative research learners must

master. First, qualitative learners must learn to

formulate research problems in qualitative research

(Table 2). Crasswell (2014) recommends that

qualitative research problems be formulated as a

single phenomenon.

Furthermore, the formulation of research

problems is narrowed down into research questions

(Table 2). The style of the formulation can take the

form of (1) the existence of problems, issues,

difficulties, dilemmas, gaps, or obstacles between

what should be (das sollen) and what happens (das

sein). The gap in question can occur in everyday life,

literature, or theory, or in practice. The issue shows

the need to be researched. (2) The formulation style

is based on curiosity.

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data:Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning

599

Tabel 2: Supporting Competencies for Reconceptualizing Empirical Data in the Undergraduate Program.

(1) Formulate the research problem precisely

(1) Can formulate research problems from the

right angle.

(2) Framed and guided by:

(a) Underlying

centr

al theory/concept

(b) Public issues

(c) Up-to-date literature to the best

of the undergraduate student's

ability.

(3) Can formulate typical qualitative research

questions guided by underlying central

theories/conce

p

ts.

(2) Operationalize and use central concepts, theories, or

sociological approach appropriately

(3) Writing a research report

It can relate empirical data findings to related literature.

3.3 Academic Tools Competency

Reconceptualization of Empirical

Data

3.3.1 The Three Stages of Coding and

Visualization of Findings

In a number of qualitative research textbooks (for

example Babbie (2021) and Newman (2014)), coding

is the main technique of qualitative data analysis. The

results of the coding are then visualized in the form

of tables, figures, diagrams, and so on. This coding

technique is adopted from the grounded research

approach in qualitative research.

Coding is assigning marks (codes) to field data. In

some qualitative methods textbooks such as Babbie

(2021) and Newman (2014), coding is the assignment

of terms (keywords, single words, or phrases) to mark

empirical phenomena. Here, first, the coding

technique contains a categorization or grouping

strategy: which phenomena are the same or similar,

and which phenomena are different. Similar

phenomena are then grouped together and given a

code (a specific term).

Second, as a keyword technique, coding is done

in stages, towards the more abstract. Thus, coding

moves from empirical phenomena to more abstract-

conceptual ones. In this regard, the three stages of

coding as proposed by Babbie (2021) and Newman

(2014) can be used. They are open coding, axial

coding, and selective coding (Figure 2).

Open coding is the first step in analyzing

empirical data. Each empirical phenomenon that is

deemed important is given a name or term. Here, the

question arises as to how to establish that one

phenomenon is important, and another is not. In this

regard, the central theory or concept used plays a

significant role. Through the procedure of

operationalizing the theory or central concept, the

researcher will have sensitivity and could judge

whether an empirical phenomenon is important or

not. Therefore, in the open coding stage, the skill of

operationalizing theories or concepts is important to

master.

In the language of Toulmin (1959, 1983, 2003)

and Booth (2008), the capacity of the theory that has

been operationalized and functions as a determinant

of data or phenomena is called a warrant. Warrant

works as a rule that guides, frames, and sorts out

which data is considered important. The

operationalized theory acts as a warrant.

The skill of using and operationalizing the

theories and concepts so that they work as warrants,

will also guide in choosing specific terminology in

giving names to data and phenomena that are

considered important. Terminology must be an

implication of the theory both in terms of reasoning

and the terms themselves.

Furthermore, in this step of coding at a higher and

more abstract level, the guidance of theory as a

warrant is even more important. In addition to the

theory-based reasoning of terminology, the choice of

diction must also correspond to the key words or

concepts that underpin the theory.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

600

Figure 2: Three levels of coding.

At an advanced stage, a few open coding that have

similarities are regrouped into one coding. This stage

is called axial coding, categorization based on the

same axis (theme). Finally, selective coding, a single

phenomenon that encompasses all aspects, themes, or

mechanisms found (. also Cresswell, 2014).

It is also important to master connectivity

strategies between categories (at least at the axial

coding level)—as suggested by Maxwell and Chmiel

(2014a). The connectivity strategy is to explore the

mechanisms that connect axial coding, such as

looking for intertwining or causal mechanisms (.

Maxwell and Chmiel 2014a). In fact, to make

connectivity easy to construct and communicate,

undergraduate students need to master the technique

of visualizing findings in the form of tables,

diagrams, matrices and so on (Mills and Hubermans,

2014).

3.3.2 The Tashawur Approach in Developing

Terminology or Coding

Tashawur is one of the academic skills in Mantiq. In

general, Mantiq is a science that has developed in the

Muslim world since the Middle Ages and was

developed from Greek Logic, but it has its own

characteristics. One of the features of Mantiq that is

relevant to this focus is the tashawur material.

Tashawur is an academic skill to organize the term

(lafadz) and the intention, understanding, meaning of

the term precisely. The precision of the meaning he

refers to by giving the term precisely is the object of

study in tashawur (. Sambas, 1996 [2017]:46-68;

Muminin, 2022; Al-Abhari, 2022; Nuruddin, 2020).

In this material on tashawur, learners become

more sensitive to words or word combinations with

the meanings they refer to. In that case, the tashawur

approach emphasizes (1) the mastery of term both

single term and composed along with the meaning or

understanding it refers to. Likewise, (2) the level of

abstraction of the term is highly emphasized in this

tashawur approach. Whether the term is at a high

level of abstraction, so that it must capture its

meaning through thought (such as the term

democracy). or the level of abstraction is low (such as

the word house). The term house can be understood

through the senses.

Examples of singular and composed terms are

house (singular term), hospital (two-word- phrase

term), or Cipto Mangunkusuomo hospital (three

words referring to one particular hospital). Even if the

term or word is only one, the intended meaning is a

single sense or thing. Also, even though the

compound Cipto Mangunkusomo Hospital consists

of three words, the phrase refers to a hospital on Jalan

Salemba in Central Jakarta.

Another typology of terms or terminology that is

important to master in the tashawur approach is

whether the term is universal or particular. The word

human is a universal term, referring to a general

figure. But President Prabowo Subianto is a specific

term. It refers to a person who is currently (2024-

2029) the president of the Republic of Indonesia.

It is also important for the competent person to

provide definitions for the terms formulate, so that

others can understand what they mean. One type of

definition that is relevant to the competence of

reconceptualizing empirical data is the essential (or

predicable) definition. An essential definition is an

answer to the question of what is (e.g. what is a

human being). Students should be able to answer that

question using five predicable terms (or kulliyatu al-

khomsah—Arabic).

Competence in taqsim (dividing) is also

important. Taqsim is the ability to trace the elements

of a terma (a word or combination of words). For

example, about a house. Taqsim answers what are the

elements of a house, or how the term house is

categorized.

So, this taqsim competency is important, because

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data:Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning

601

it enables the scholar to categorize words. He can

specify the elements of a word, or the further

categories of a term. They can show that a few words

are connected because they have an upper, more

abstract word that can overshadow other words below

it.

So, there are three competencies from the

tashawur approach that can be integrated with the

three levels of coding, namely (1) typology of terms

(lafadz), (2) essential definitions-predicable

(kulliyatul khomsah), and (3) taqsim (division). The

three components of tashawur can enhance the

mastery of key terms, the meanings they refer to, and

the tinkering with words, terms, or concepts. The

tashawur approach allows undergraduate researchers

to thematize and formulate their field findings into a

more abstract conceptual level, through a three-level

coding approach aided by the tashawur approach.

3.3.3 Deduction, Induction, and Abduction

Reasoning

Deductive, inductive and abductive reasoning are the

three patterns of reasoning underlying qualitative

research. They are used in specific proportions and

are different from the proportions and composition of

their use in quantitative research. Even within

qualitative research itself, the proportion of each of

the three reasoning patterns used varies during the

research design stage (Thornberg, 2022), during data

collection (Kennedy and Thornberg, 2018), and

during data analysis (Reichertz, 2014).

Deduction reasoning is the first step in

reconceptualizing empirical data. Deductive

reasoning serves as a guide (warrant, sensitizing)

(Booth et.al., 2008) and how abstract reasoning or

concepts are operationalized to the empirical level (in

the form of indicators or parameters; Babbie, 2021).

At the research design stage, this deductive reasoning

guides the research angle, formulates the research,

and guides the research questions (even the key

concepts in the theory we use are explicit in the

formulation of research questions). The central theory

or concept that has been operationalized to the

empirical level (indicator or parameter) also becomes

a reference in collecting data to analyzing data and

writing reports. The use of deductive reasoning in

1

The author uses the term working hypothesis (which is

widely used in qualitative research) instead of the term test

hypothesis. The main difference between the two types of

hypotheses is the use of theory. In a test hypothesis, the

domain is deductive reasoning, and the aim is to prove the

theory. Whether the field data is in accordance with the

theory or even contradicts the theoretical reasoning. The

qualitative research is relatively minimal. It is not as

strong as quantitative research.

Furthermore, this deductive reasoning becomes

the main ingredient of abductive reasoning. In simple

terms, abductive reasoning can be understood from

three angles. (1) The deductive dimension means

operationalizing the theory into a few working

hypotheses.

1

The best working hypothesis is selected

and used. The less appropriate working hypothesis is

put away first, maybe it will be used later. So,

abduction reasoning is the use of the most appropriate

working hypothesis, serving as a research guide, and

the working hypothesis is shifted and changed

according to the data findings. Here, abduction

reasoning relies on the operationalization of theory

from deduction reasoning.

In the abduction reasoning, there is an element of

looking for "potential suspects". The hypothesis

becomes the focus and guide to find evidence or data

so that the "suspect" becomes the "defendant".

Furthermore, the data is collected, so that it becomes

evidence and the defendant. However, once the

complete data has been fulfilled, the third principle,

namely retroduction, applies.

(2) Retroduction is the back-and-forth

principle. It connects the hypothesis as the initial

idea (which ks potential suspects) with empirical

data. The hypothesis work serves as a guide to find

data that will serve as proof. However, it is possible

that the data collected is different and even

contradicts the working hypothesis. In that case, the

working hypotheses are shifted or even changed. It is

possible that several hypotheses that were previously

stored are then chosen again to become working

hypotheses because they are in accordance with field

data. Then a working hypothesis is taken from the

working hypothesis bank and becomes a replacement

for the original working hypothesis. If it does not

exist, appropriate concepts or theories are sought.

If a central theory or concept that is relevant and

overshadows the field data findings is obtained, and

has been operationalized into a working hypothesis,

then the working hypothesis is used as a claim or

thesis. In addition to the change in position from

working hypothesis to claim (thesis), the claim also

serves to overshadow the field findings. Field

findings are the proof of the thesis. The fidelity to

result is theory verification, theory rejection, or theory

modification. In contrast, working hypotheses function as

warrant or sensitizing. The working hypothesis becomes a

guide in collecting and analyzing data. Once the data

obtained is different from the working hypothesis, let alone

contradictory, then the working hypothesis is changed, and

adjusted to the field findings.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

602

Interpretation of

Level 3

Interpretation of

Level 2

Interpretati

on of

Level 1

Adapted from Wuisman 2024:6.

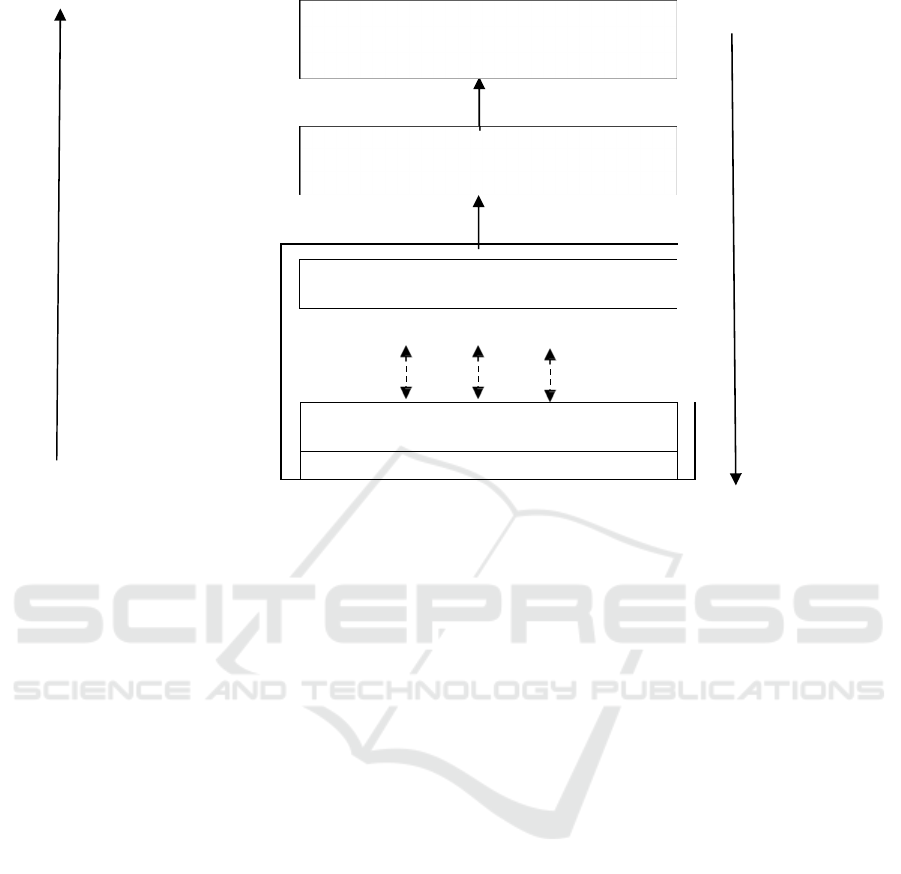

Figure 3: Inductive and Deductive Reasoning Patterns.

data findings and the back and forth principle of the

relationship between theory (working hypothesis)

and field data is referred to as the principle of

retroduction (Downdie, 2019).

Inductive reasoning, on the other hand, is the

opposite of the deductive pattern (Figure 3). Inductive

reasoning is a pattern of reasoning that draws

abstractions from empirical phenomena into

conceptual-abstract things. There are three forms of

this induction strategy. The first is the generalization

strategy (Kennedy & Thornberg, 2018) or also

referred to as the categorization strategy (Maxwell

and Chmiel, 2014a), or what in this article is referred

to as coding. Thornberg and Charmaz, 2014). Second,

is the strategy of connecting between these categories

as discussed in the coding section (Maxwell and

Chmiel, 2014a),

The third strategy is to explore emic

interpretations and then frame them ethically (Willig,

2014). Various results of emic categorization

(especially in the open coding stage) are framed and

grouped from the point of view of the theory used

(Wuisman, 2024). Here, theory serves as a guide for

categorization or thematization of coding. This stage

of analysis was carried out at the axial coding level.

The results of this three-level coding process produce

categorizations, themes, or mechanisms that are more

abstract, conceptual, and in accordance with the

central concept or theory used.

The author uses the term working hypothesis

(which is widely used in qualitative research) instead

of the term test hypothesis. The main difference

between the two types of hypotheses is the use of

theory. In a test hypothesis, the domain is deductive

reasoning, and the aim is to prove the theory. Whether

the field data is in accordance with the theory or even

contradicts the theoretical reasoning. The result is

theory verification, theory rejection, or theory

modification. In contrast, working hypotheses

function as warrant or sensitizing. The working

hypothesis becomes a guide in collecting and

analyzing data. Once the data obtained is different

from the working hypothesis, let alone contradictory,

then the working hypothesis is changed, and adjusted

to the field findings.

4 CONCLUSION

From a pedagogical point of view, the ability to

reconceptualize empirical data is categorized as

higher order thinking. Students not only record and

record empirical data. In fact, he must be able to

dialectic the conceptual guidelines he has with his

empirical data findings. The results of the dialectic

are then categorized, thematized, and visualized by

framing them on their theoretical foundation. In fact,

Classification system, name, category,

type

Basic conceptual framework

Dimensions and key concepts

Conceptualization- Abstraction

Operationalization of the concept

Participant/subject understanding

meaningful signs

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data:Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning

603

dialectic is already in the category of synthesis,

because it tries to interrelate the theoretical

foundations he has with the tendencies and reasoning

of the empirical data he encounters.

The above synthesis process is also rooted in the

sociological research tradition itself. The research

methods literature in sociology often emphasizes that

the categorization, thematization and visualization of

research findings should be consistent with the

paradigmatic position of sociology. Indeed, as a

multi-paradigmatic science, the discipline of

sociology demands that the qualitative research

conducted by a researcher must be in line with the

key ideas of the overarching sociological paradigm.

Reconceptualization of empirical data must also be

guided and in line with the overarching sociological

paradigm.

REFERENCES

Al-Abhari, Sheikh Atsirudin, 2020 [no year]. Kitab

Ishaghuji. Translation of Abi Kafa Bihi HSB.

Mukjizat.

Arnold, Christine et.al. (Editors), 2020. Learning

Outcomes, Academic Credit, and Student Mobility.

Montréal & Kingston: Queen's University McGill-

Queen's University Press.

Atkinson, Maxine P and Kathleen S Lowney, 2016. In

Trenches: Teaching and Learning Sociology. New York:

W.W. Norton.

Babbie, Earl, 2021. The Practice of Social Research.

Fifteenth Edition. Boston: Cengage.

Burawoy, Michael, 2005, For Public Sociology.

American Sociological Review 70: 4. Doi:

10.1177/000312240507000102.

Burawoy, Michael, 2009. The Extended Case Method: Four

Countries, Four Decades, Four Great Transformations

and One Theoretical Tradition. Berkeley: University of

California Press.

Cabrera, Sergio A & Stephen Sweet (Editors), 2023.

Handbook of Teaching and Learning in Sociology.

Glethenham: Edward Edgard Publishing.

Cannella, Gaile S, 2022. Ethical Entanglements:

Conceptualizing 'Research Purposes/Design in the

Contemporary Political World'. In Uwe Flick (Editor).

The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research Design.

London & Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Copi, Irving M; Carl Cohen, and Victor Rodych, 2019

[1953]. Introduction to Logic. Fifteenth Edition. New

York: Routledge.

Creswell, John W., 2016. 30 Essential Skills for the

Qualitative Researcher. Thousand Oaks Road,

California: Sage Publications.

Creswell, John W. & Cheryl N. Poth, 2018. Qualitative

Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five

Approaches. Fourth Edition. Thousand Oaks,

California: Sage Publications Ltd.

Creswell, John W. & J. David Creswell, 2018. Research

Design Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods

Approaches. Fifth Edition. London: Sage.

Denzin, Norman K., 2014. Writing and/as Analysis or

Performing the World. In Uwe Flick (Editor). The Sage

Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. London &

Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Dodgson, Joan E., 2019. Reflexivity in Qualitative

Research. Journal of Human Lactation 1-3. DOI:

10.1177/0890334419830990.

Ferguson, Susan J. and Stephen Sweet, 2023. The Core: The

Sociological Literacy Framework. In Sergio A. Cabrera

& Stephen Sweet. Handbook of Teaching and Learning

in Sociology. Glethenham: Edward Edgard Publishing.

Gob, Giampietro, 2008. Re-conceptualizing

Generalization: Old Issues in a New Frame. In Pertti

Alasuutari, Leonard Bickman, & Julia Brannen. The

Sage Handbook of Social Research Methods. London

& Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hayon, Yohanes Pande, 2000. Logika Prinsip-Prinsip

Bernalar Tepat Lurus dan Teratur. Jakarta: Penerbit

ISTN.

Hurley, Patrick J. & Lori Watson, 2018 [2012]. A Concise

Introduction to Logic. 13th Edition. Boston: Cengage

Learning.

Kane, Danielle, 2023. Disciplinary-Specific Critical

Thinking in Sociology. In Sergio A. Cabrera & Stephen

Sweet. Handbook of Teaching and Learning in

Sociology. Glethenham: Edward Edgard Publishing.

Kane, Danielle; and Kristin Otto, 2017. Critical

Sociological Thinking and Higher-level Thinking: A

Study of Sociologists' Teaching Goals and

Assignments. Teaching Sociology 1-11. DOI:

10.1177/0092055X17735156.

Kawulich, Barbara; Mark W. J. Garner; Claire Wagner,

2009. Students' Conceptions-and Misconceptions-of

Social Research. Qualitative Sociology Review Volume

V, Issue 3.

Kelle, Udo, 2014. Theorization from Data. In Uwe Flick

(Editor). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data

Analysis. London & Thousand Oaks: Sage

Publications.

Kennedy, Brianna L. and Robert Thornberg, 2018.

Deduction, Induction, and Abduction. Uwe Flick

(Editor). The Sage Book of Qualitative Data Collection.

London & Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Marshall, Catherine and Gretchen B. Rossman, 2016.

Designing Qualitative Research. Sixth Edition.

London: Sage.

Medley-Rath, Stephanie, 2023. Designing Core Major

Courses: Methods. In Sergio A. Cabrera & Stephen

Sweet. Handbook of Teaching and Learning in

Sociology. Glethenham: Edward Edgard Publishing.

Maxwell, Joseph A., 2022. Generalization as an Issue for

Qualitative Research Design. In Uwe Flick (Editor).

The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research Design.

London & Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

604

Maxwell, Joseph A. and Margaret Chmiel, 2014a. Notes

Toward a Theory of Qualitative Data Analysis. In Uwe

Flick (Editor). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data

Analysis. London & Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Maxwell, Joseph A. and Margaret Chmiel, 2014b.

Generalization in and from Qualitative Analysis. In

Uwe Flick (Editor). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative

Data Analysis. London & Thousand Oaks: Sage

Publications.

Mekolichick, Jeanne, 2022. Undergraduate Research in

Sociology: Cultivating the Sociological Imagination.

Mieg, Harald A et.al (Editors). The Cambridge

Handbook of Undergraduate Research. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Miles, Mattew B and A. Michael Huberman, 2014.

Qualitative Data Analysis: a Methods Sourcebook.

Third Edition. Sage Publication.

Miles, Cindy L. & Cynthia Wilson, 2004. Learning

Outcomes for the Twenty First Century: Cultivating

Student Success for College and the Knowledge

Economy. New Directions for Community Colleges,

No. 126: 87-100.

Moleong, Lexy J., 2019 [1988]. Metodologi Penelitian

Kualitatif. Bandung: Remaja Rosdakarya.

Morse, Janice M., 2006. Reconceptualizing Qualitative

Evidence. Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 16 No. 3,

March 2006 415-422 DOI:

10.1177/1049732305285488.

Muminin, Iman S, 2022. Belajar Mudah Ilmu Mantiq:

Ulasan Memudahkan Atas as-Sullam al-Munawroq

Karya al-Akhdari. Jakarta: Penerbit Qaf.

Mulyana, Deddy, 2010. Metodologi Penelitian Kualitatif.

Bandung: Remaja Rosdakarya.

Neuman, W. Lawrence. 2014. Social Research:

Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Fifth

Edition. Boston: Pearson Education Inc.

Nind, Melanie (Editor), 2023. Handbook of Teaching and

Learning Social Research Methods.Glethenham:

Edward Edgard Publishing.

Nind, Melanie & Sarah Lewthwaite, 2019. A Conceptual-

Empirical Typology of Social Science Research

Methods Pedagogy. Research Papers in Education,

DOI: 10.1080/02671522.2019.1601756.

Nuruddin, Muhammad, 2020. Ilmu Mantik: Panduan

Mudah dan Lengkap untuk Memahami Kaidah

Berpikir. Depok: Keira Publishing.

Orange, Amy, 2023. Facilitating Learners' Reflexive

Thinking in Qualitative Research Courses. In Nind,

Melanie. Handbook of Teaching and Learning Social

Research Methods. Glethenham: Edward Edgard

Publishing.

Perdue, William D., 1986. Sociological Theory. Mayfield

Pub Co.

Rahmat, Abdi, 2020. Rencana Pembelajaran Semester

Metode Penelitian Kualitatif Tahun 2020. Jakarta:

Program Studi Pendidikan Sosiologi Universitas Negeri

Jakarta.

Reichertz, Jo, 2014. Induction, Deduction, Abduction. In

Uwe Flick (Editor). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative

Data Analysis. London & Thousand Oaks: Sage

Publications.

Ritzer, George, 1975. Sociology: A Multiple Paradigm

Science. Allyn and Bacon.

Sambas, Syukriadi, 1996 [2017]. Mantik: Kaidah Berpikir

Islami Thinking Rules. Bandung: Remaja Rosdakarya.

Schreier, Margrit, 2018. Sampling and Generalization. In

Uwe Flick (Editor). The Sage Book Qualitative Data

Collection. London & Thousand Oaks: Sage

Publications.

Suryana, Asep, 2012. Menangkap Tanda-Tanda Bermakna:

Strategi Pembelajaran Riset Kualitatif untuk Program

Sarjana. Jurnal Komunitas Prodi Sosiologi Universitas

Negeri Jakarta.

------------------, 2020. Membangun Keadilan Kota dari

Bawah: Gerakan Lokal Muhammadiyah di Post-

Suburban Depok. Depok: Disertasi Departemen

Sosiologi Universitas Negeri Jakarta.

Swedberg, Richard, 2017. Theorizing in Sociological

Research: A New Perspective, a New Departure?.

Annual Review of Sociology 43:189-206.

Https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev- soc-060116-053604.

Swedberg, Richard, 2016. Before theory comes theorizing

or how to make social science more interesting. The

British Journal of Sociology 67 (1): 5-22. DOI:

10.1111/1468- 4446.12184.

Swedberg, Richard, 2012. Theorizing in sociology and

social science: turning to the context of discovery.

Theory and Society 41:1-40. DOI 10.1007/s11186-011-

9161-5.

Tambunan, Shuri Mariasih Gietty and Manneke Budiman,

2022. Undergraduate Research in Indonesia. Edited by

Mieg, Harald A. et.al. (Editors) The Cambridge

Handbook of Undergraduate Research. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press 2022.

Thorn, Richard & Peter H. Sydenham, 2008. Developing a

measuring systems body of knowledge. Measurement

41: 744-754.

Thornberg, Robert, 2022. Abduction as a Guiding Principle

in Qualitative Research Design. In Uwe Flick (Editor).

The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research Design.

London & Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Thornberg, Robert and Kathy Charmaz, 2014. Grounded

Theory and Theoretical Coding. In Uwe Flick (Editor).

The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis.

London & Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Wagnera, Claire; Mark Garnerb and Barbara Kawulichc,

2011. The State of the Art of Teaching Research

Methods in the Social Sciences: Towards a Pedagogical

Culture. Studies in Higher Education Vol. 36, No. 1.

Willig, Carla, 2014. Interpretation and Analysis. In Uwe

Flick (Editor). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Data

Analysis. London & Thousand Oaks: Sage

Publications.

Wuisman, J.J.M, Jan, 2004. Realisme Kritis: Pemahaman

Baru tentang Penelitian Ilmu Sosial. Dalam Jurnal

Masyarakat dan Budaya Vol. VI No. 2. Jakarta: Pusat

Penelitian Kemasyarakatan dan Kebudyaan Lembaga

Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia

Reconceptualizing Empirical Data:Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills in Undergraduate Qualitative Methods Learning

605

Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, Olga et.al. (Editors). 2018.

Assessment of Learning Outcomes in Higher

Education: Cross-National Comparisons and

Perspectives. Switzerland: Springer International

Publishing.

ICHELS 2024 - The International Conference on Humanities Education, Law, and Social Science

606