Intersectionality Lens for Smartphone Adoption Among Female

Older Adults

Jia Yue Tan

1a

, Kin Meng Cheng

2b

, Ah Choo Koo

1,* c

and Chui Yin Wong

3d

1

Faculty of Creative Multimedia, Multimedia University, Malaysia

2

Faculty of Creative Industries, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia

3

The Design S ty, Malaysia

1161 .my,

*

ackoo@mmu.edu.my, chuiyinwong@gmail.com

Keywords: Female Older Adults, Intersectionality, Smartphone, Adoption.

Abstract: Older adults are usually underrepresented in the discourse of smartphone adoption and are often subjected to

stereotypes that create negative perceptions of their ability to use the technology. In a gender-stereotyped

society, female older adults face even more challenging situations for their technology adoption experiences.

Intersectionality has emerged as a dynamic theory that recognises individuals as members of multiple groups

can simultaneously experience various forms of privilege, vulnerability, and disadvantages. To examine the

adoption of smartphones among female older adults, we adapt the intersectionality lens to explain the adoption

or non-adoption issues and factors. The objectives of this study are to explore intersectionality in smartphone

usage for female older adults, review their usage and needs through related literature. This review study aims

to identify motivating factors and barriers for smartphone technology adoption among female older adults in

Malaysia. The findings show that using an intersectionality lens, the study identified how smartphone use by

female older adults is influenced by a range of interconnected factors. This study offers valuable insights for

scholars conducting similar research and highlights the importance of considering diverse and interconnected

factors in technology adoption.

1 INTRODUCTION

The evolving nature of technology implies the

necessity of users continually acquiring new technical

know-how to use mobile devices, yet this poses a

significant challenge for older generations in keeping

pace with its new interfaces (UI), applications and

interaction modes compared to the younger

generations. In the gendered inequality and

stereotyped society, especially in the male-dominated

field of science and technology (S&T) area, female

users of this advanced technology, especially in their

older age, are stereotyped as un-skilful users or non-

technological users. This user group is perceived

negatively on their ability to use technology, and they

are underrepresented in the discussions of mobile

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9902-2215

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9111-3988

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1706-1796

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2144-368X

*

Corresponding author

technology adoption. In general, most literature

focuses on older adults.

This paper aims to study female older adults’

adoption of mobile technology such as smartphone

apps and services in their everyday lives. The specific

Research Objectives (RO) to review the smartphone

usage and needs by female older adults through

related literature.

The first section of this paper presents a

theoretical lens to cover more deeply on technology

adoption or non-adoption issues through the

complexity of the intersection nature of groups,

culture, and demographics attributes that exist in

societal issues of technology adoption in the juncture

of ageing society and advanced AI-related

technological era. The second section is the scoping

review, explaining the key findings of reviews. The

Tan, J. Y., Cheng, K. M., Koo, A. C. and Wong, C. Y.

Intersectionality Lens for Smartphone Adoption Among Female Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0013295400004557

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Creative Multimedia (ICCM 2024), pages 5-13

ISBN: 978-989-758-733-7; ISSN: 3051-6412

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

5

third section is to present the review findings in a

Framework and explain the details of the framework.

1.1 Intersectionality Lens as the

Theoretical Foundation

Intersectionality, a theoretical lens developed by

Kimberlé W. Crenshaw in 1989, originated from the

advocacy for the rights of black women in the United

States during the 1970s and 1980s (Rodriguez, 2018).

Crenshaw contended that the structural systems

exhibited a failure to acknowledge the interconnected

nature of the oppressive experiences encountered by

women of colour. These systems concentrated

exclusively on gender and race as separate entities,

disregarding their intersectionality (Rodriguez,

2018).

Crenshaw defined intersectionality as a

metaphorical representation of a crossroad or traffic

at a junction. It signifies the convergence of multiple

influences originating from several factors, which

collectively shape the interconnected experiences or

circumstances of a person or a group (Rodriguez,

2018, p.431). In simple understanding, Crenshaw

illustrated intersectionality as:

“The metaphor of a crossroads or traffic at an

intersection… arguing that diverse factors flow from

different directions and only by looking at the

interconnection of these factors is one able to

understand the causes, characteristics, and

consequences of events that happen at the

intersection” (Rodriguez, 2018, p. 431).

The topic of intersectionality has been widely

discussed for many years, especially in the field of

feminist research (Slowey, 2022). Currently, it is used

as a flexible research model that is utilised in different

fields such as health research, ageing and technology,

and information systems research. It goes beyond the

traditional frameworks that focuses on only one

aspect (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2020).

The statement recognises that individuals own

numerous identities, such as age, class, ability,

religion, education and migratory status.

As members of multiple groups, individuals can

simultaneously experience various forms of privilege,

vulnerability, and disadvantages (Rodriguez, 2018;

WHO, 2020).

1.2 Intersection and Interconnected

Factors

Scholar activists including Crenshaw have used

intersectionality to urge for a deeper look at the

interconnected factors (based on gender, class, race

and other categories) that determine power, privilege

and oppression of a marginalised group (Rodriguez,

2018; Fehrenbacher & Patel, 2020).

Presently, intersectionality has emerged as a

dynamic research paradigm that seeks to move

beyond the use of traditional ‘single-axis framework’

(one that considers single, rather than the multiple

intersecting categories of identity) that shape

individuals’ experiences (WHO, 2020). It begins with

the idea that individuals have multiple identities (i.e.,

age, class, ability, religion, education, migration

status, etc.), and that as members of more than one

‘group’, they can experience different forms of

privilege, vulnerability and (or) disadvantages at the

same time (Rodriguez, 2018; WHO, 2020). For

example, gender is only one of the social factors that

people face in every part of the world. It is still

insufficient to address either a dominant or

subordinate position (Ceia et al., 2021; Rodriguez,

2018) without taking into consideration other social

constructs or categories of identity.

Nevertheless, this study did not adhere to a pure

intersectional gender analysis that centres more on the

voices of people who are subjected to multiple,

simultaneous forms of oppression to understand the

complexities of the inequalities and their

interconnections, particularly where ‘gender’ is

prioritised as the primary entry point into the analysis

(UN Women, 2020; WHO, 2020). This study adapted

intersectionality in a flexible way to explore how

female older adults’ use of smartphones

simultaneously embodies multiple elements and

characteristics (i.e., age, educational attainment,

digital literacy, environmental influence, etc.), rather

than being necessarily associated with oppression and

discrimination. These grouping social identities and

contextual factors would be considered as elements to

be explored and reviewed in this study to understand

the depths of how Malaysian female older adults use

their smartphones in real-life contexts.

1.3 Application of Intersectionality

The use of the intersectionality lens for any service

design has emphasised the multiple influences of

individuals’ characteristics and social identities (i.e.,

gender, socioeconomic status, race, age, language

ability group, physical ability or disability group,

immigrants or non-immigrants, digitally literate and

low literate group) which have the nuance influence

of the everyday lives of that individual or group

(Corus & Saatcioglu, 2015). The author further

elaborates that the group or subgroup, if to be

analysed deeper, may have a further understanding of

ICCM 2024 - The International Conference on Creative Multimedia

6

how the identity factors (listed above) affect the

quality of life or well-being of a group of people.

These influences can lead to stereotyping (grouping)

and add complexity to understand the context of how

society works.

This theory is useful for discussing how

Malaysian female older adults use smartphones to

contribute to their family and the community (i.e.,

role as a family caregiver, in managing household,

social participation, etc.), for their personal interests

and well-being, as well as their strength in coping

with contingency situations (i.e., the impact of the

COVID-19), all of which should be acknowledged.

The smartphone usage experiences and behaviours

among female and male older adult users might also

differ. Currently, the use of mobile apps and services

have become common: banking, purchasing goods

using e-wallet, e-banking and verification of

accounts, communication using instant messages, etc.

These activities require the use of smart technology

and users’ interaction with digital interfaces.

The theory of intersectionality has contributed to

understanding and improving telecommunication or

mobile service design by offering “a holistic look at

the co-created nature of services and it can be

instrumental in designing tailored and fair services to

improve consumer and societal well-being”, as

mentioned by Corus and Saatcioglu (2015) who

explained the complexity of the user’s identities and

how it comes to affect their usage purpose and

behaviours.

1.4 Global Ageing: Patterns, Meanings

and Consequences

The world is currently undergoing a notable

demographic change known as the "ageing

population phenomenon." This shift is mostly caused

by causes such as longer life expectancy and

decreasing birth rates (UN, 2020). The prevalence of

older individuals worldwide has been steadily

increasing, resulting in around 9% of the population

today being 65 years or older. According to

projections from the United Nations (2020), this

percentage is expected to double and reach over 16%

by 2050.

Nevertheless, the categorisation of ‘older adults’

differs among nations and regions. Low-and-middle-

income countries (LMICs) generally classify those

aged 60 and above as older adults, whereas Western

countries commonly establish the threshold at 65 and

above (UN, 2019; WHO, 2021). In this study, the

term ‘older adults’ will refer to persons from both age

groups, encompassing a wide range of opinions on

ageing (APA, n.d.).

In Malaysia, individuals aged 60 years and above

are considered ‘senior citizens’ or ‘older adults.’

Approximately 7% of the population in Malaysia is

65 years or older, which classifies the country as an

‘ageing nation’ (World Bank Group, 2020;

MyGovernment Portal, 2022). Projections indicate

that the percentage will increase twofold to reach

14% by 2040, indicating Malaysia's shift towards

being an ‘aged nation’ (World Bank Group, 2020).

Comprehending the patterns of ageing worldwide

and the diverse criteria for categorising older

individuals in different nations is essential for

policymakers, researchers, and healthcare

practitioners. These changes have important

consequences for healthcare, social welfare, and

economic policies, emphasising the requirement for

comprehensive and age-friendly programmes to

tackle the changing demands of older individuals and

guarantee their welfare and social integration.

Additional study is important to investigate the

complex and diverse aspects of ageing and devise

efficient approaches to address the difficulties and

possibilities linked to worldwide ageing.

1.4.1 Exploring the Complexities of

Worldwide Ageing and the Impact of

Smartphone Culture: Obstacles and

Possibilities

The world is currently experiencing the phenomenon

of global ageing and the rapid progress in technology

are fundamentally transforming societies around the

globe, giving rise to a multitude of obstacles and

opportunities in the realm of current events and global

matters. There is a notable change in the world's

population, with a larger percentage of older adults

leading to an increase of the phenomenon of ageing

populations (UN, 2019; WHO, 2020).

Simultaneously, the widespread use of smartphones

and rapid progress in technology is revolutionising

the ways in which individuals engage, work and

reside (Pew Research Centre, 2021).

1.4.2 Exploring the Phenomenon of

Smartphone Culture

Smartphones have become an indispensable part of

everyday life, with an estimated 6.4 billion

individuals globally utilising these gadgets (Statista

Research Department, 2021a, 2021b). These gadgets

offer a wide range of features that allow users to

remain connected, receive information and

Intersectionality Lens for Smartphone Adoption Among Female Older Adults

7

participate in various activities using mobile apps and

services (Rao & Troshani, 2007; GSMA, 2020).

1.4.3 Analysing the Patterns of Smartphone

Usage in the Older Adults Population

The older adult population has increasingly

recognised the significance of smartphones, leading

to their designation as "silver surfer adopters of

smartphones" (Wong et al., 2020). Several studies

have extensively examined the usage of smartphones

among the older adult population, providing valuable

insights into the diverse and frequently restricted

involvement with these technological devices

(Rosales &

& Fernández-Ardèvol, 2019). This question

is especially relevant for the older adults’ population,

a group that may face distinct physical and functional

difficulties (Nikou, 2015). The integration of

Information and Communication Technology (ICT)

has the potential to greatly improve the quality of life

for older persons, notwithstanding the presence of

digital inequities (Francis, 2019).

According to the Malaysian Communications and

Multimedia Commission (MCMC, 2022), there is a

growing trend among older people in Malaysia

smartphone technology between 2018 and 2021, with

more than 80% (online survey with 1916

respondents) of individuals aged 65 and over using

smartphones. The main purposes for which older

individuals utilise smartphones are communication,

socialisation, work, entertainment, and religious

activities (Ahmad et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2017).

Although the older adult population is

increasingly using smartphones, they still encounter

hurdles such as struggling with unfamiliar interfaces

and technologies, cost problems, and concerns about

cybersecurity (Azuddin et al., 2014; Mohadis & Ali,

2015; Wong et al., 2020). Nevertheless, older

individuals also demonstrate favourable perspectives

towards smartphones, highlighting the significance of

compatibility and the aspiration to acquire and

enhance digital proficiencies (Yong, 2016; Wong et

al., 2018, 2020).

1.4.4 Digital Divide due to Demographic

Factor

The convergence of international ageing patterns and

the prevalence of smartphone culture poses both

obstacles and prospects for individuals, communities

and governments around the globe. Technology can

improve the lives of older individuals by making it

easier for them to get healthcare and stay connected

with others. However, it also brings up worries about

some older people being left out and unequal access

to digital resources (Eurostat, 2021; European

Commission, 2020).

To effectively navigate the challenges posed by

global ageing and smartphone culture, it is crucial to

comprehend and tackle the intricate relationship

between demographic changes and technological

progress. By acknowledging the difficulties and

advantages brought about by these occurrences,

society might strive towards cultivating inclusive and

sustainable communities in an ever-growing digital

realm.

2 A REVIEW ON THE ADOPTION

OF SMARTPHONES BY

FEMALE OLDER ADULTS

The study adopted a scoping review (Munn et al.,

2018), specifically to address this research question:

To review the smartphone usage and needs by female

older adults through some related literature.

Relevant articles were discovered through

ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis, Frontiers and

Google Scholar databases, ranging from 2012 to

2023.

Keyword searches included terms such as

"smartphones," "mobile technologies,"

"female/women," "older adults/elderly/senior

citizens/ageing," "mobile usage/adoption," and

"intersectionality." The review focused on studies

examining the adoption of smartphones by female

older adults and the factors influencing this adoption.

Terms excluded from the search were "male/men

older adults smartphone users," "feature phones,"

"landline phones," and "pre-smartphone era."

Finally, 11 articles were selected, and their key

findings are discussed in the following sections.

2.1 Intersecting Factors Identified from

Female Older Adults on

Smartphone Usage or Adoption

Technology adoption is not just adopting the

hardware, but also the software and its application

services. How technology is adopted by older adults,

must be observed from their needs and personal

attributes, especially the motivation to learn and use

it. Internal and external factors of “push and pull” are

the motivational factors for older adults and their

gender roles to influence the use of smartphones. The

equality of access to technology and the issue of the

technology divide can be explained through the lens

of intersectionality.

ICCM 2024 - The International Conference on Creative Multimedia

8

Our previous work conducted a study on

smartphone usage and experience of female older

adults (Tan et al. 2022). The study involved a group

of smartphone users in the Central City area around

Kuala Lumpur- Klang area (cities or townships area),

where the use of smartphones is quite vibrant and

active for all age group users, including older adults.

Many older adults have some forms of experience

using smartphones. Their experiences are also

unique, which is worth exploring. Two were recruited

in a pilot study, and seven were recruited in the main

study, to explore what these female older adults did

with their smartphones and how they perceived their

male counterparts (spouse, friends or peers) in using

smartphones.

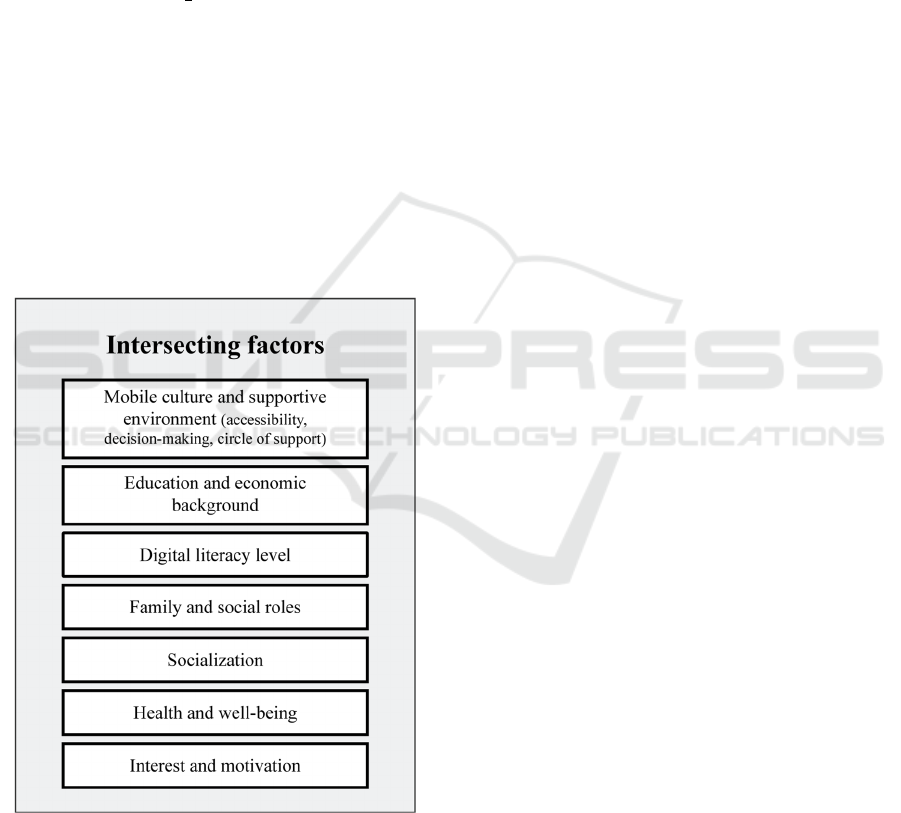

The findings showed several intersecting factors

that influenced the relationship between female older

adults and their smartphone intimacy as illustrated in

Figure 1. These factors have surfaced positively

contributing to the usage of smartphones. We showed

how the relationship was established through

evidence of usage and experience sharing

in the

verbatim form mentioned by the research

participants.

Figure 1: Intersecting factors that influence the

relationships (positively) between female older adults and

their smartphone usage (Tan et al., 2022, p. 1292).

“These factors identified are the general trends of

findings based on this group of participants only. The

intersections of gender grouping, or variables (male

and female) have shown the differences in mobile

usage and experiences. The intergenerational group

(elderly and young people) has shown differences in

perception toward each other’s free time and ability

to help troubleshoot on mobile phones. The culture or

ethnicity attribute did not show much difference in

general, but the socio-economic (i.e., mobile

expenditure, self-investment in digital skill class),

educational background, and supportive environment

possessed significant impacts on mobile phone usage

and experiences” (Tan et al., 2022, p. 1294).

nvironmental factors such as infrastructure, and

mobile phone usage and culture are also considered

the key factors to encourage or discourage the usage

of smartphones.

2.2 Female Older Adults’ Adoption of

Mobile and Smartphone

Technology

Research (Cajamarca & Herskovic, 2022; Ganito,

2018; Hardill & Olphert, 2012) has shown that daily

use of mobile phones by female older adults has

become more comfortable, particularly because it

increases their sense of safety, mobility, flexibility

and independence. Apart from communication, more

female older adults are discovered to use ICT (i.e.,

smartphones, computers, applications, assistive

technologies) for various purposes, including online

shopping, entertainment, health-related and work

purposes (Cajamarca & Herskovic, 2022; Ganito,

2018).

In terms of negative experiences, female older

adult users reported fear while interacting with more

complex features and functions (i.e., online banking),

and have expressed concern about becoming overly

reliant on technology use (Cajamarca & Herskovic,

2022). Research (Hardill & Olphert, 2012; Kim et al.,

2016; Xue et al., 2012) also found that age-related

barriers (severe decline in physical and cognitive

abilities) were the primary cause of female older

adults’ limited phone access. It has somehow

impacted their abilities and needs to use phones,

especially for socialising. However, most of these

perspectives are primarily from Westernised or

developed countries (i.e., UK, US, Portugal), and

their findings may not directly apply to older women

in the context of developing countries like Malaysia.

In Malaysia, recent studies from 2022 have shed

light on digital technology adoption among the

Malaysian female older adults. Lee et al. (2022)

investigated the spending patterns on

telecommunications within Malaysian households in

2019, utilising microdata on income and

Intersectionality Lens for Smartphone Adoption Among Female Older Adults

9

expenditures. The study revealed that households

headed by older adults, particularly female older

adults or those solely comprised of older adults,

exhibited lower monthly telecommunications

spending, attributed to reduced household incomes.

This lower expenditure suggested that a significant

number of Malaysian older adults acquire

smartphones either as gifts or second-hand devices

from family members. The research also pointed out

a noticeable disparity in telecommunications

spending among households led by female older

adults, which limited their access to telemedicine,

online communication, and economic services such

as e-wallets.

Additionally, Liew et al. (2022) undertook a

qualitative study of smartphone usage among lower-

income (B40) older women residing in rural areas of

Malaysia. The study identified physical, cognitive,

psychological, and usability challenges in

smartphone usage, emphasising the necessity for a

supportive environment, in-person guidance and age-

friendly app interfaces to enhance learning and

usability for this demographic.

Nevertheless, most existing studies in Malaysia

that focused on gender about usage behaviour and

adoption of ICT technologies have mainly

investigated the interests of younger age groups (< 50

years old) or all age groups in general (Ahmad et al.,

2019; Aziz & Aziz, 2020; Maon et al., 2021). The

literature review reveals a significant gap in research

centred on ageing and gender in Malaysia,

particularly ones that explore female older adult

users’ perspectives, experiences, and issues regarding

their adoption of mobile technologies (i.e.,

smartphones, computers, app software etc.).

Additionally, there is a lack of an in-depth and

multidimensional view that considers the spectrum of

users such as age, gender, socioeconomic status,

ethnicity, abilities and so on which can influence

individuals’ or groups’ experiences of smartphone

use.

To address the research objective of reviewing

smartphone usage and needs among female older

adults through related literature, with a particular

focus on Malaysian research, a scoping review was

conducted. This review highlights a notable gap in

research centred on ageing and gender in Malaysia,

particularly on exploring the perspectives,

experiences, and issues of older female users

regarding their use of smartphone apps and services.

The literature review identified three main topics:

"Global Ageing: Patterns, Meanings, and

Consequences," which analyses the overall trends and

effects of ageing on a global scale; "Exploring the

Complexities of Worldwide Ageing and the Impact of

Smartphone Culture: Obstacles and Possibilities,"

which investigates the challenges and potential

benefits of smartphone usage among older adults; and

"Mobile Technology Use and Intersectionality,"

which examines how elements such as age, gender,

socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and abilities shape

the experiences (and trends) of individuals and groups

about smartphone use. These concerns emphasise the

importance of using a comprehensive approach to

understand the specific challenges and requirements

of older women in relation to mobile technology,

especially in Malaysia (Tan et al., 2022).

2.3 Stereotype on Smartphone Usage:

Age and Gender Context

It is imperative to recognise that age and gender

stereotypes in relation to technology persist, and these

stereotypes often have negative impacts on female

older adults’ representation and use of digital

technology (Balsamo, 2014, as cited in Gales &

Hubner, 2020). These stereotypes can also result in

biased perceptions regarding one’s abilities and

interests, as well as those of others. Previous studies

(Comunello et al., 2016; Gales & Hubner, 2020) have

uncovered gender-related interests in technology

usage, where women’s use of mobile phones was

typically associated with an interest in

communication (depicted as being ‘chatterboxes’),

caregiving or online shopping. Such stereotypes,

however, do not apply to men. Meanwhile, men were

perceived by women to have more interest in STEM

areas, which was attributed to their masculine nature

(physical strength and competency) (Gales &

Hubner, 2020). When relating gender and technology

competence, the masculine assumption collectively

shapes the negative stereotype that women are ‘less

skilled or competent users,’ and ‘less interested in

ICT’, while men are perceived positively as ‘tech-

savvy’ and ‘having higher competence’ when it

comes to technology adoption and usage performance

(Comunello et al., 2016; Gales & Hubner, 2020). The

negative stereotypes are thereby even more

pronounced for female older adult users. The

assumption regarding their technology usage is not

only based on gender but also their age, as there is

also the biased perception that older individuals are

less competent than younger ones when it comes to

the adoption of mobile phones (Comunello et al.,

2016).

Despite widespread stereotypes about older

women and technology use, existing literature has

provided significant insights (see Section 2.2) into

ICCM 2024 - The International Conference on Creative Multimedia

10

their adoption of technologies as the digital landscape

evolves.

2.3.1 Female Older Adults’ Perception of

Oneself and Others regarding

Smartphones/ Technology Usage

Gales and Hubner (2020) conducted qualitative in-

depth interviews with female older adults (aged 65-

75) in Germany to gather insights on their self-

perceptions and perceptions of others (i.e., their

peers) regarding technology usage (smartphones,

computers etc.). Older women in the context of Gales

and Hubner’s study view their interest in technology

as stemming from individual preferences rather than

societal influences. This suggests that internal

motivations and personal experiences play a

significant role in their technology adoption. When

assessing others, these women rely on societal

stereotypes, believing men are naturally more

inclined towards technology, especially in

mechanical and technical aspects. In contrast, these

women associate women’s interest in technology

more with social and communicative purposes, such

as using smartphones for chatting or video calls. This

dichotomy between self-perception and group

perception highlights a psychological barrier where

individuals may feel competent personally but

perceive their group as generally less competent.

Furthermore, the same study found that older women

often use age to justify their perceived lack of

technological competence, which can serve as a

significant psychological barrier (Gales & Hubner,

2020). They rationalise their difficulties with

technology as an inevitable part of ageing, they not

only perceive themselves as less competent but also

perceive their peers, especially those older than

themselves, as even less competent.

The concept of the bias blind spot (Pronin et al.,

2002, as cited in Gales & Hubner, 2020), where

individuals perceive themselves as less biased than

others, is evident in the findings. This creates a

psychological barrier that prevents them from

recognising their own biases in avoiding adopting

certain technologies.

he study highlights the intricate intersection of

gender, age, and technology stereotypes, showing

that older women's self-perceptions and their views of

others are shaped by deeply ingrained societal norms.

To empower older women in the digital age, it is

essential to address these stereotypes and promote a

more inclusive approach to technology design and

education (Gales & Hubner, 2020).

3 DISCUSSIONS

The study emphasises the enduring prejudices

associated with age and gender in connection to

technology, and how these stereotypes significantly

influence the way female older adults acquire and use

smartphones. The prevalence of these prejudices

frequently results in biased perceptions regarding the

technical aptitude of older women, reinforcing

negative assumptions, despite evidence indicating

their growing ease and competency in using mobile

devices. Research emphasises that older women may

have a positive personal interest in technology, but

societal preconceptions affect their perception of

others' ability. This division generates a mental

obstacle where individuals feel capable on an

individual level but view their group as less capable,

intensified by age-related explanations for perceived

difficulties with technology.

The intersectionality framework provides a

comprehensive and detailed comprehension of how

aspects such as age, gender, socioeconomic status,

and supportive contexts influence the experiences of

female older adults using smartphones. This method

emphasises notable discrepancies in the availability

of resources, knowledge of mobile technologies, and

social assistance systems among individuals

belonging to this specific group. To tackle these

problems, it is necessary to implement concrete

actions such as customised training programmes,

enhanced accessibility features in smartphone design,

and the promotion of optimistic stories to counter

prejudices and empower older women in their

utilisation of mobile technology. Addressing these

intricacies is crucial for improving the involvement,

autonomy, and general welfare of older women in the

digital era.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study contribute to several

important research areas, including geron-technology

which is an interdisciplinary field that combines

gerontology (ageing) and technology (Teh et al.,

2015), and women’s perspectives by exploring

female older adults’ experiences and behaviours in

using smartphones. The lens of intersectionality can

be utilised in the research of technology adoption,

which is a good move, where the nuance of the

experiences of different sub-group users is to be

considered too. It is to encourage scholars to design

research that is sensitive to such complexities and

Intersectionality Lens for Smartphone Adoption Among Female Older Adults

11

interdependent disadvantages that play a key role in

the construction of experiences and value in

technology adoption research by the disadvantaged

groups. Any policy or promotion of technology usage

should emphasise the use of qualitative research with

consideration of better theories to guide research to

be more inclusive like what the current theory can

offer to researchers and policymakers. Awareness of

theories should be encouraged in research. In sum, the

intersectionality lens offers considerable potential in

understanding complex and multi-dimensional

technology adoption to all ages/ groups and

subgroups. This study offers valuable insights for

scholars conducting similar research and highlights

the importance of considering diverse and

interconnected factors in technology adoption.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially supported by the

International Development Research Centre Grant

(IDRC, Canada) and Carleton University through a

grant entitled “Designing Mobile Service Design for

Ageing Women in Malaysia”. This was one of the

projects, namely Project ID 50, under Gendered

Design for STEAM in LMICs. Grant ID was MMUE

190212/ ID 50, 2020-2022.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, N. A., Zainal, A., Kahar, S., Hassan, M. A. A., &

Setik, R. (2016). Exploring the needs of older adult

users for spiritual mobile applications. Journal of

Theoretical and Applied Information Technology,

88(1), 154–160.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303919536_

Exploring_The_Needs_of_Older_Adult_Users_for_Sp

iritual_Mobile_Applications

American Psychological Association (APA). (n.d.). Age.

Retrieved March 6, 2020, from

https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-

guidelines/bias-free-language/age

Arthanat, S., Vroman, K., Lysack, C., & Grizzetti, J.

(2018). Multi-stakeholder perspectives on information

communication technology training for older adults:

implications for teaching and learning. Disability and

Rehabilitation Assistive Technology, 14(5), 453-461.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17483107.2018.1493752

Ashton, J. (2020). Mobile Culture vs Culturally Mobile?

The University of British Columbia.

https://blogs.ubc.ca/etec523/2020/05/27/mobile-

culture-vs-culturally-mobile/

Azuddin, M., Malik, S. A., Abdullah, L. M., & Mahmud,

M. (2014). Older people and their use of mobile

devices: Issues, purpose and context. The 5th

International Conference on Information and

Communication Technology for the Muslim World,

ICT4M 2014, 1–6.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ICT4M.2014.7020610

Cajamarca, G., & Herskovic, V. (2022). Understanding

experiences and expectations from active, independent

older women in Chile towards technologies to manage

their health. International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 166(April), 102867.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102867

Ceia, V., Nothwehr, B., & Wagner, L. (2021). Gender and

Technology: A rights-based and intersectional analysis

of key trends. In Oxfam.

https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-

publications/gender-and-technology-a-rights-based-

and-intersectional-analysis-of-key-trends/

Comunello, F., Ardèvol, M. F., Mulargia, S., & Belotti, F.

(2016). Women, youth and everything else: age-based

and gendered stereotypes in relation to digital

technology among elderly Italian mobile phone users.

Media, Culture & Society, 39(6), 798–815.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716674363

Corus, C., & Saatcioglu, B. (2015). An intersectionality

framework for transformative services research.

Service Industries Journal, 35(7), 415–429.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2015.1015522

Fehrenbacher, A. E., & Patel, D. (2020). Translating the

theory of intersectionality into quantitative and mixed

methods for empirical gender transformative research

on health. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22(sup1), 145–

160. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1671494

Ganito, C. (2018). Gendering Old Age: The Role of Mobile

Phones in the Experience of Aging for Women. In

Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including

subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and

Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics): Vol. 10926 LNCS

(pp. 40–51). Springer International Publishing.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92034-4_4

GSMA. (2020). Connected women: The mobile gender gap

report 2020.

https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-

content/uploads/2020/05/GSMA-The-Mobile-Gender-

Gap-Report-2020.pdf

Hardill, I., & Olphert, C. W. (2012). Staying connected:

Exploring mobile phone use amongst older adults in the

UK. Geoforum, 43(6), 1306–1312.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.03.016

Lee, Y., Din, H. M., Wong, C. Y., Lai, W. T., & Koo, A. C.

(2022). A study of female- and older adults-led

households’ telecommunication expenditure in digital

Malaysia. In Proceedings of the International

Conference on Technology and Innovation

Management (ICTIM 2022) (Vol. 1, pp. 307–320).

Atlantis Press International BV.

https://doi.org/10.2991/978-94-6463-080-0_27

Liew, E. J. Y., Teh, P.-L., Ewe, S. Y., & Chong, C. L.

(2022). Understanding Challenges as Needs:

ICCM 2024 - The International Conference on Creative Multimedia

12

Smartphone Usage Among Malaysian Older Women in

Rural Areas. 2022 IEEE International Conference on

Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management

(IEEM), 1201–1205.

https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEM55944.2022.9989579

Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission.

(2022). Hand Phone Users Survey 2021 (Issue July).

https://www.mcmc.gov.my/skmmgovmy/media/Gener

al/pdf2/FULL-REPORT-HPUS-2021.pdf

Mohadis, H. M., & Ali, N. M. (2015). A study of

smartphone usage and barriers among the elderly. 2014

3rd International Conference on User Science and

Engineering (i-USEr), 109–114.

https://doi.org/10.1109/IUSER.2014.7002686

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C.,

McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic

review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when

choosing between a systematic or scoping review

approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1),

143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

MyGovernment Portal. (2022). Vulnerable Groups: The

Elderly/Senior Citizens.

https://www.malaysia.gov.my/portal/content/30740

Nikou, S. (2015). Mobile technology and forgotten

consumers: the young-elderly. International Journal of

Consumer Studies, 39, 294-304.

Pew Research Center. (2021). Technology use in the U.S.

https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/09/01/the-

internet-and-the-pandemic/

Pronin, E., Lin, D., & Ross, L. (2002). The bias blind spot:

perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personal. Soc.

Psycho/. Bull. 28, 369-381. https://doi.org/L0.1177/

0146167202286008

Rao, S., & Troshani, I. (2007). A conceptual framework and

propositions for the acceptance of mobile services.

Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic

Commerce Research, 2(2), 61–73.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer2020014

Rodriguez, J. K. (2018). Intersectionality and Qualitative

Research. In C. Cassell, A. L. Cunliffe, & G. Grandy

(Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business

and Management Research Methods: History and

Traditions (pp. 429–461). SAGE Publications Ltd.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526430212.n26

Rosales, A. & Fernández-Ardèvol, M. (2019). Smartphone

Usage Diversity among Older People. Human–

Computer Interaction Series.

Slowey, M. (2022). Intersectionality: Implications for

Research in the Field of Adult Education and Lifelong

Learning. In K. Evans, W. O. Lee, J. Markowitsch, &

M. Zukas (Eds.), Third International Handbook of

Lifelong Learning (pp. 1–21). Springer, Cham.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67930-9_5-1

Tan, J. Y., Koo, A. C., Wong, C. Y., & Lai, W. T. (2022).

Intersectionality Lens to Female Elderly's Mobile

Usage Experience under COVID-19: An Intimate or

Intimidating Relationship?. International Journal of

Technology, 13(6).

https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i6.5920

United Nations. (2020). World population ageing 2020:

Living arrangements of older persons. In United

Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs,

Population Division.

https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.u

n.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd-

2020_world_population_ageing_highlights.pdf

UN Women. (2020). Intersectional feminism: what it

means and why it matters right now.

https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/6/exp

lainer-intersectional-feminism-what-it-means-and-

why-it-matters

World Bank Group. (2020). A Silver Lining: Productive

and Inclusive Aging for Malaysia.

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia/publi

cation/a-silver-lining-productive-and-inclusive-aging-

for-malaysia

World Health Organisation [WHO]. (2020). Incorporating

intersectional gender analysis into research on

infectious diseases of poverty: A toolkit for health

researchers.

https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/97892400084

58

Wong, C. Y., Ibrahim, R., Hamid, T. A., & Mansor, E. I.

(2018). Mismatch between older adults’ expectation

and smartphone user interface. Malaysian Journal of

Computing, 3(2), 138.

https://doi.org/10.24191/mjoc.v3i2.4889

Wong, C. Y., Ibrahim, R., Hamid, T. A., & Mansor, E. I.

(2020). Measuring expectation for an affordance gap on

a smartphone user interface and its usage among older

adults. Human Technology, 16(1), 6–34.

https://doi.org/10.17011/ht/urn.202002242161

Xue, L., Yen, C. C., Chang, L., Chan, H. C., Tai, B. C., Tan,

S. B., Duh, H. B. L., & Choolani, M. (2012). An

exploratory study of ageing women’s perception on

access to health informatics via a mobile phone-based

intervention. International Journal of Medical

Informatics, 81(9), 637–648.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.04.008

Intersectionality Lens for Smartphone Adoption Among Female Older Adults

13