Speaking the Same Language or Automated Translation? Designing

Semantic Interoperability Tools for Data Spaces

Maximilian St

¨

abler

1 a

, Tobias Guggenberger

2

, DanDan Wang

3

, Richard Mrasek

4

, Frank K

¨

oster

1

and Chris Langdon

5

1

German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute for AI Safety and Security, Ulm, Germany

2

Fraunhofer ISST, Dortmund, Germany

3

T-Systems International GmbH, Bonn, Germany

4

T-Systems International GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany

5

Drucker School of Business, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, U.S.A.

Keywords:

Data Spaces, Semantic Interoperability, Design Principles, Data Ecosystem.

Abstract:

This paper tackles the challenge of semantic interoperability in the ever-evolving data management and shar-

ing landscape, crucial for integrating diverse data sources in cross-domain use cases. Our comprehensive ap-

proach, informed by an extensive literature review, focus-group discussions and expert insights from seven pro-

fessionals, led to the formulation of six innovative design principles for interoperability tools in Data Spaces.

These principles, derived from key meta-requirements identified through semi-structured interviews in a focus

group, address the complexities of data heterogeneity and diversity. They offer a blend of automated, scalable,

and resilient strategies, bridging theoretical and practical aspects to provide actionable guidelines for semantic

interoperability in contemporary data ecosystems. This research marks a significant contribution to the do-

main, setting a new design approach for Data Space integration and management.

1 INTRODUCTION

In today’s digital era, data is a critical asset driv-

ing innovation and economic growth. The European

Data Strategy (European Commission, 2020) aims to

create a single market for data within Europe, em-

phasizing inter-organizational data sharing to foster a

competitive and innovative digital economy through

seamless and secure data exchange. This strategy

supports the development of new products, enhances

decision-making, and contributes to societal benefits

such as improved healthcare and sustainable devel-

opment (Hutterer et al., 2023; Guggenberger et al.,

2024).

Data Spaces and Data Ecosystems are central to

this strategy. Data Spaces facilitate the sovereign and

secure exchange of data between organizations, while

Data Ecosystems integrate multiple Data Spaces, cre-

ating environments that support data-driven innova-

tion across various domains and industries.

Our research addresses the challenge of achiev-

ing semantic interoperability within and across Data

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1311-3568

Spaces. We aim to develop tools supporting specific

ontologies and data structures within domains while

facilitating their integration across different domains,

preventing isolated silos and supporting a wide array

of applications (Otto, 2022). Semantic interoperabil-

ity is crucial for data integration, ensuring different

systems can correctly interpret and utilize exchanged

data. Addressing the gap in semantic interoperabil-

ity research compared to other layers, our paper of-

fers new insights and solutions to this critical aspect

of data interoperability.

Before introducing the research questions, we

clarify the significance of the three desirable attributes

of semantic interoperability: automatable, scalable,

and resilient. Automatable interoperability reduces

manual intervention and errors, increasing efficiency.

Scalability ensures a system can handle increasing

data and participants without compromising perfor-

mance, supporting the expansion of data ecosystems.

Resilience maintains system functionality and perfor-

mance despite variations in data quality, formats, and

sources, ensuring robust data exchange amid disrup-

tions or changes.

Stäbler, M., Guggenberger, T., Wang, D., Mrasek, R., Köster, F. and Langdon, C.

Speaking the Same Language or Automated Translation? Designing Semantic Interoperability Tools for Data Spaces.

DOI: 10.5220/0012916700003825

In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST 2024), pages 209-217

ISBN: 978-989-758-718-4; ISSN: 2184-3252

Copyright © 2025 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

209

Our research aims to develop tools for the integra-

tion, management, and interconnection of data across

various domains. Our research question is:

RQ: How can tools be designed for automat-

able, scalable, and resilient semantic interop-

erability within and across Data Spaces?

Our approach involves a two-pronged strategy. First,

we conduct a literature review and expert interviews

to gather and analyze existing knowledge, establish-

ing meta-requirements (MR). Using these MRs, we

derive design principles (DPs) for tools embodying

automation, scalability, and resilience, essential for

semantic interoperability between Data Spaces (Curry

et al., 2022).

By harmonizing disparate data models and stan-

dards, our approach lowers data sharing and integra-

tion barriers. Successful development and implemen-

tation of these principles promise to streamline data

integration processes across domains, paving the way

for a unified and efficient data ecosystem. This trans-

formation could revolutionize the data landscape in

Europe, setting a global benchmark for data interop-

erability and integration (Jabbar et al., 2017; Ouksel

and Sheth, 1999).

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 pro-

vides foundational knowledge, delineating the litera-

ture streams for developing MRs. Section 3 details

our research methodology. The MRs, derived from

expert interviews, are presented in Section 4. Build-

ing upon these MRs, Section 5 elaborates on the DPs.

Section 6 discusses the broader implications of our

findings, acknowledges study limitations, and high-

lights potential future research avenues, concluding

with a summative overview.

Main Contribution. This paper advances semantic

interoperability in heterogeneous data ecosystems and

Data Spaces. The main contributions are:

• Conceptual Clarity: Clear differentiation be-

tween Data Spaces and traditional database sys-

tems, enhancing the understanding of their unique

roles within data ecosystems.

• Meta-Requirements and Design Principles:

Identification of key meta-requirements for ser-

vices promoting semantic interoperability, form-

ing the basis for novel design principles ensuring

automation, scalability, and resilience in data ex-

change processes.

• Methodological Rigor: Comprehensive method-

ological framework detailing each study stage,

providing a robust basis for the study’s conclu-

sions.

• Timely and Relevant Research: Addressing

contemporary issues within the European Data

Strategy, aligning contributions with strategic ob-

jectives to foster a unified European data market,

with practical implications for policy and industry

stakeholders.

• Innovative Approach: Dual focus on meta-

requirements and design principles to tackle se-

mantic interoperability challenges, providing ac-

tionable guidelines for developing tools support-

ing data integration and management across di-

verse domains.

In summary, the paper bridges critical gaps in

the literature by offering a theoretically and empir-

ically grounded framework for advancing semantic

interoperability in data spaces, thus supporting the

broader goal of creating interconnected and efficient

data ecosystems.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

This chapter outlines the theoretical foundations of

dataspaces and semantic interoperability, crucial for

deriving design principles (DPs).

2.1 Dataspaces

Originally conceptualized by Franklin and Halvey

(Franklin et al., 2005; Halevy et al., 2006), datas-

paces have evolved as an alternative to traditional re-

lational databases. Table 1 presents diverse defini-

tions of dataspaces.

Numerous dataspace approaches, such as Gaia-

X, Catena-X, IDS, FAIR dataspaces, and SOLID,

emphasize technical interoperability (European Com-

mission, 2020). However, full technical compatibility

remains unachieved. Analysis of various reference ar-

chitectures reveals core components essential for con-

trolled and secure data exchange (Curry, 2020a; Curry

et al., 2022; Otto et al., 2022; Theissen-Lipp et al.,

2023):

1. Providing and Accessing Data (Connector): Man-

ages data according to usage policies, ensuring

data sovereignty.

2. Intermediation Services (Metadata broker, App

Store): The Resource Catalog lists available of-

fers, characteristics, and conditions of use.

3. Identity Management and Secure Data Exchange:

Ensures participant identity verification and trans-

action security.

WEBIST 2024 - 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

210

Table 1: Extract of definitions of datspaces - the complete overview is shown in (Curry, 2020b).

Definition Source

”Dataspaces are not a data integration approach; rather, they are more of a

data co-existence approach. The goal of dataspace support is to provide base

functionality over all data sources, regardless of how integrated they are.”

(Halevy et al., 2006)

“A dataspace system processes data, with various formats, accessible through

many systems with different interfaces, such as relational, sequential, XML,

RDF, etc. Unlike data integration over DBMS, a dataspace system does not

have full control on its data, and gradually integrates data as necessary.”

(Wang et al., 2016)

“Dataspace is defined as a set of participants and a set of relationships among

them.”

(Singh and Jain, 2011)

4. Management Components: Manages participant

activities such as registration, deregistration, re-

vocation, suspension, and monitoring.

Dataspaces offer benefits to businesses (e.g., in-

dustrial data sharing, access to heterogeneous data

ecosystems), individuals (e.g., control over personal

data), science (e.g., impact of research data), and

governance/public sector (e.g., data commons for im-

proved services) (Curry et al., 2022).

Dataspaces provide federated and self-determined

interoperability for specific use cases (Otto, 2022).

Examples include Catena-X for the automotive indus-

try and the Mobility Dataspace (MDS). The European

Commission envisions a singular European datas-

pace (Theissen-Lipp et al., 2023), extending beyond

enterprise boundaries to include distributed, feder-

ated, and decentralized data systems. Interoperability

across dataspaces (dataspace mesh) poses challenges

in scalability, efficiency, and governance (Drees et al.,

2021).

2.2 Semantic Interoperability

”Semantic interoperability ensures that these

exchanges make sense—that the requester and

the provider have a common understanding of

the “meanings” of the requested services and

data.” - (Heiler, 1995)

Semantic interoperability, recognized since (Heiler,

1995), emphasizes meaningful data exchange through

shared understanding. (Ouksel and Sheth, 1999) cate-

gorizes interoperability into system, syntax, structure,

and semantics levels.

Syntactic heterogeneity involves differences in

machine-readable data representations, while struc-

tural interoperability concerns data modeling con-

structs. Despite advances in systems, syntactic, and

structural interoperability, solutions for semantic in-

teroperability are still elusive (Ouksel and Sheth,

1999).

Many web services technologies assume seman-

tic homogeneity, implying a universal vocabulary

(Uschold and Gruninger, 2004). However, histori-

cal attempts to integrate systems under a single vo-

cabulary have largely failed (Haslhofer and Klas,

2010). Recognizing semantic heterogeneity is essen-

tial for seamless system connectivity (Uschold and

Gruninger, 2004).

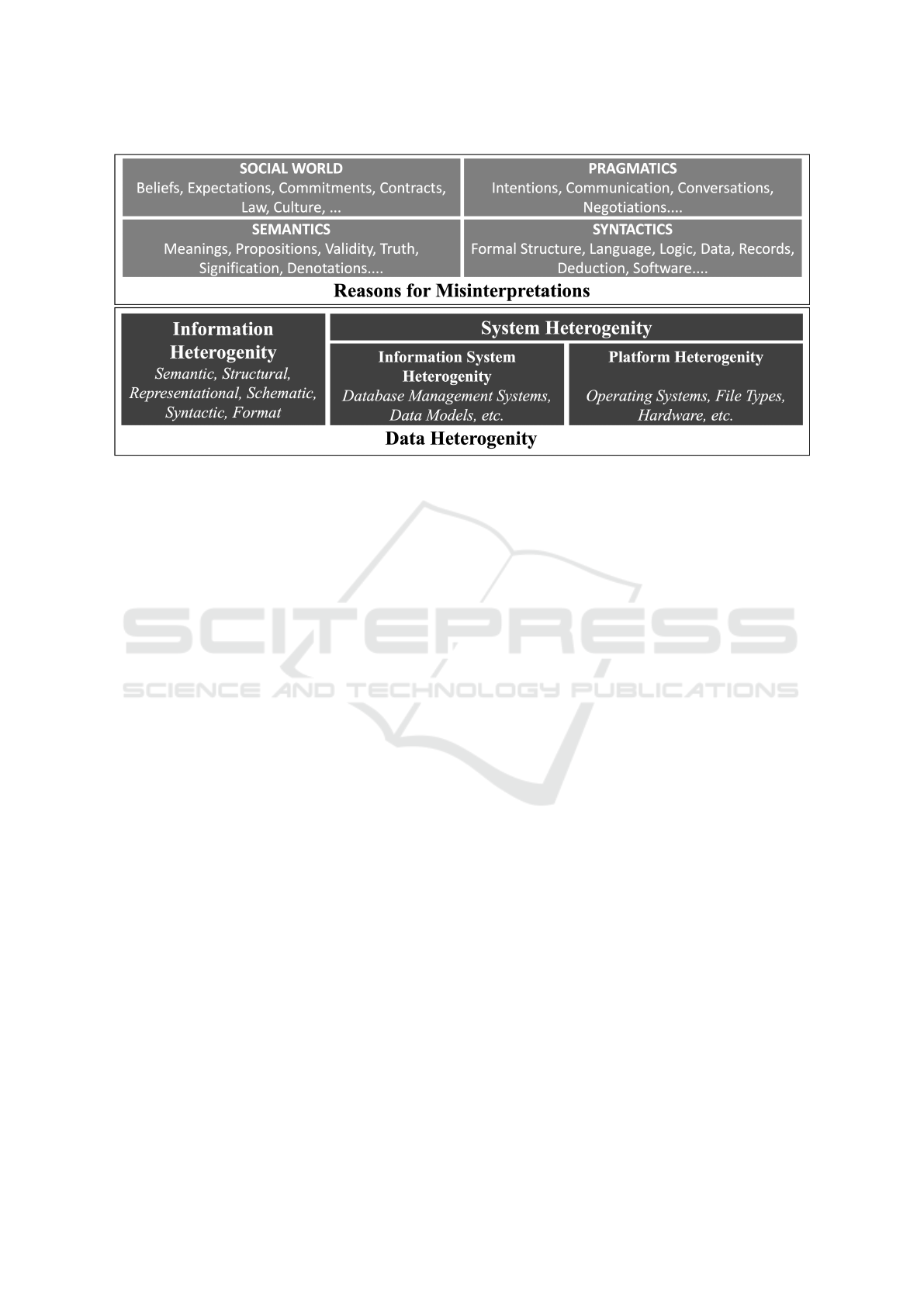

Figure 1 illustrates the challenges of heterogene-

ity in information systems and its implications for se-

mantic interoperability. ”Data Heterogeneity” refers

to physical variances in data, while ”Reasons for Mis-

interpretations” highlights subjective sources of error.

In dataspaces, characterized by distributed, au-

tonomous, diverse, and dynamic information sources,

accessing relevant and accurate information is com-

plex (Ouksel and Sheth, 1999). Semantic interoper-

ability and semantics-based technologies are funda-

mental for market success and establishment of datas-

paces (Theissen-Lipp et al., 2023; Otto et al., 2022;

Curry et al., 2022). Integration of complex systems

across domains necessitates a unified framework for

effective communication (Boukhers et al., 2023).

While the necessity for such services is estab-

lished (Boukhers et al., 2023), concrete implementa-

tion proposals or practical tests are lacking. This gap

motivates our proposal of DPs for such a service.

3 METHODOLOGY

To develop theoretically and empirically grounded

DPs for interoperability tools for dataspaces, we em-

ployed a structured methodology. We will discuss

data collection, analysis, and DP generation. First, we

conducted a structured literature review to gather ex-

isting knowledge as preliminary design requirements.

Second, we refined our understanding of the prob-

lem space and restructured the requirements. Finally,

we developed an interview guideline for conducting

semi-structured interviews to triangulate our prelim-

Speaking the Same Language or Automated Translation? Designing Semantic Interoperability Tools for Data Spaces

211

Figure 1: Heterogeneity in information systems and reasons for misinterpretations of data according to (Wenz et al., 2021).

inary findings with empirical data. We performed a

thematic analysis of focus group discussions to iden-

tify key themes and topics, which then structured the

interview guide, ensuring questions explored relevant

issues in depth.

3.1 Literature Review

We conducted a structured literature review following

established guidelines (Webster and Watson, 2002;

Zhang et al., 2011; Levy and Ellis, 2006; Vom Brocke

et al., 2015). We identified relevant databases (IEEE

Xplore, ACM Digital Library, ScienceDirect, Wiley

InterScience, SCOPUS) and used filtering functions

to include only peer-reviewed publications with full-

text access. Using iterative search strings based on

Schoormann et al. (Schoormann et al., 2018), we per-

formed the search as shown in Table 2.

This process yielded 69 distinct publications. Af-

ter filtering by title, abstract, and full text, 31 publi-

cations remained. We scanned references from these

publications, adding three further studies, resulting in

a total of 31 publications.

3.2 Focus Groups and Expert

Interviews

Informed by the literature review, we structured pre-

liminary requirements for semantic interoperability

tools. These were evaluated and refined in focus

groups formed by the core working group ”Seman-

tic Modeling and Interoperability” from a family of

projects funded by the German Federal Ministry for

Economic Affairs and Climate Protection. We used

seven remote meetings for this purpose.

The focus group has 16 members from industry,

research, and the public sector, with expertise in inter-

operability, data systems, application programming,

semantics, operators, and end users.

We developed a semi-structured interview guide-

line based on the literature review and focus group

discussions. Semi-structured interviews allowed ex-

perts to provide input on specific topics. After seven

interviews with experts (Table 3), theoretical satura-

tion was reached.

3.3 Design Principle Generation

DPs are prescriptive guidelines codifying design

knowledge about a specific class of artifacts (Chan-

dra et al., 2015; Gregor, 2006; Baskerville et al.,

2018). They guide developers to increase design pro-

cess efficiency and communicate design knowledge

with stakeholders (Chandra et al., 2016; Mcadams,

2003; Hevner et al., 2004). DPs are central to de-

sign science research (Sein et al., 2011; M

¨

oller et al.,

2020), covering core components of a design theory:

causa finalis, materialis, formalis (Jones and Gregor,

2007). We followed guidelines from M

¨

oller et al.

(M

¨

oller et al., 2020) and used Chandra et al.’s (Chan-

dra et al., 2015) template for documentation. Our

approach combined a literature review, focus group

meetings, and expert interviews to elicit MRs. We de-

veloped a preliminary list of requirements, discussed

them in focus groups, and refined the problem space

and solution objective. This informed the question-

naire for expert interviews, and we finally evaluated

the DPs argumentatively.

WEBIST 2024 - 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

212

Table 2: Search Strings.

Search Strings

S1 (semantic* AND (automated* OR resilient OR scalable OR shared OR sharing))

S2 (interoperability* OR inter-operability)

S3 (dataspace* OR data space OR datenraum)

S S1 AND S2 AND S3

Table 3: Expert Overview.

Expert Occupation Company / Industry

E1 Data Manager (PhD) Ministry of Transport and Mobility Transition

E2 Research Associate Data Business Institute for Software and Systems Engineering

E3 Senior Expert Cyber Physical Systems Automotive Supplier (> 200.000 employees)

E4 Lead Business Consultant (PhD) Large consulting company (> 10.000 employees)

E5 Head of Advisory Council Dynamic Data Economy Foundation

E6 Research Associate Industry 4.0 Innovation Large Software Company (> 100.000 employees)

E7 Research Associate Data Science and AI Institute for Applied Information Technology

4 FORMULATING

META-REQUIREMENTS

This section presents the MRs for services that enable

semantic interoperability in dataspaces to be automat-

able, scalable, and resilient. Derived from literature

and expert interviews, Table 4 provides an overview

of the MRs and their basis. Below, we describe the

five MRs for semantic interoperability with selected

quotations to illustrate their meaning.

Meta-Requirement # 1: Contextualization and

metadata: Effective semantic interoperability re-

quires appropriate metadata and context. E1 and E4

emphasize the importance of ”metadata or extended

metadata” and ”semantic models” for accurate data

interpretation. Comprehensive metadata visibility, as

noted by E2, is crucial for understanding data prove-

nance and usage. Curry et al. (Curry, 2020b) state

that dataspaces must support various data models and

query languages. 71.43% of experts highlighted the

importance of contextualization and metadata, crit-

icizing current approaches as incomplete or insuffi-

cient (E1, E2, E4, E6).

Meta-Requirement # 2: Resilience of data: An

artifact must handle diverse data qualities and for-

mats. E1 stresses the need for systems that can ”make

the data comparable through automation,” while E5

emphasizes ensuring the integrity and authenticity

of data. Approaches from ontology matching and

alignment can help overcome semantic heterogeneity

(Otero-Cerdeira et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2021; Ard-

jani et al., 2015; Uschold and Gruninger, 2004). Re-

silience and scalability are deemed critical by 57.12%

of experts.

Meta-Requirement # 3: Scalability: Effective

semantic interoperability requires scalable solutions

accessible to users regardless of their technical back-

ground. E1 and E6 highlight the need for automated

approaches to homogenize data. E7 mentions the ease

of transforming data formats as crucial. Scalability

ensures dataspaces can expand and accommodate in-

creasing data and complexity (Theissen-Lipp et al.,

2023). 57.12% of experts emphasized scalability, of-

ten linked with automation and resilience (E1, E2,

E7).

Meta-Requirement # 4: Ease of use and simplic-

ity: Widespread adoption depends on simplicity and

user-friendliness. E4 calls for “intuitive design” and

open-source artifacts. E3 and E6 highlight the im-

portance of reducing effort and not requiring exten-

sive expertise. Natural language interfaces, like those

provided by AI and LLMs, make systems more ap-

proachable for non-experts (Wang et al., 2023; Pan

et al., 2023). Boukhers et al. (Boukhers et al., 2023)

suggest AI algorithms for semantic interoperability.

42.85% of experts stressed simplicity.

Meta-Requirement # 5: Community-driven

learning: Leveraging collective intelligence enhances

and evolves artifacts over time. 28.57% of experts

noted this as an important characteristic. E1, E5 em-

phasize updating data schemas and learning domain-

specific characteristics (E6). Dataspaces must han-

dle the volatility of the data landscape (Curry, 2020a;

Drees et al., 2021; Franklin et al., 2005). Community

feedback leads to continuous refinement and effec-

tiveness (Otero-Cerdeira et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2021;

Ardjani et al., 2015; Uschold and Gruninger, 2004).

These MRs form a cohesive framework for an ar-

tifact that enables semantic interoperability. Address-

Speaking the Same Language or Automated Translation? Designing Semantic Interoperability Tools for Data Spaces

213

Table 4: Meta-Requirements Overview. In addition to the Meta-Requirement and Description columns, the Experts col-

umn lists which experts have named requirements that can be assigned to the respective meta-requirement. Meta-requirements

have been ordered by importance, starting with the most important MR.

MR Meta-Requirement Description Experts #Experts (%)

1 Contextualization and

metadata

The artifact should require the provision

of data context and mandatory metadata

(specifics to be defined) for effective use

E1, E2,

E4, E6,

E7

5 (71,43%)

2 Resilience of data The artifact must be resistant to different data

qualities, data types and data formats in order

to ensure practical usability

E1, E3,

E5, E6

4 (57, 12%)

3 Scalability The artifact should be designed in such a way

that it can be automated so that people with-

out specialized knowledge can use it effec-

tively to facilitate scalability in the complex

semantic landscape

E1, E2,

E5, E6

4 (57, 12%)

4 Ease of use and sim-

plicity

To encourage broad engagement, the artifact

should be designed for extreme simplicity

E3, E4,

E7

3 (42,85%)

5 Community-driven

learning

The artifact should be able to continuously

learn and improve by taking into account

feedback from the community and users

E1, E7 2 (28,57%)

ing these core needs allows the proposed artifact to

serve as a robust, inclusive, and adaptive framework

for data management. Chapter 5 derives DPs based

on these MRs.

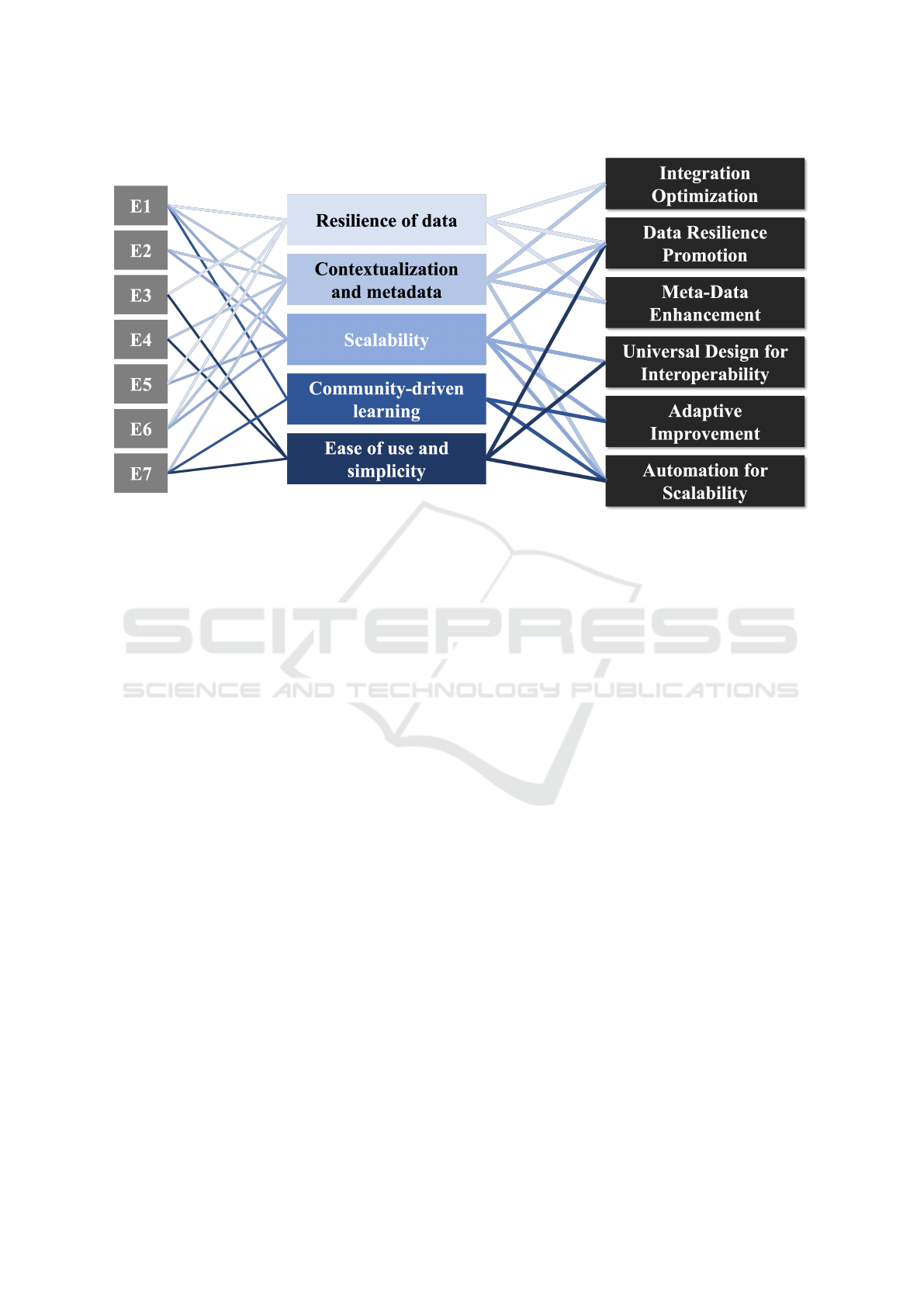

5 DESIGN PRINCIPLES

The following DPs were formulated based on the

MRs to connect various data sources, enhance data

resilience, and promote an inclusive and adaptive en-

vironment for data exchange in dataspaces. Figure 2

shows the fulfillment of the MRs by the DPs (M

¨

oller

et al., 2020). The seven principles are discussed be-

low using the format of Chandra et al. (Chandra et al.,

2015). A preliminary evaluation using Iivari et al.’s

(Iivari et al., 2021) framework is also provided.

5.1 Design Principle Description

DP1: Integration Optimization: Design interoper-

ability artifacts to optimize the seamless integration

of diverse data sources, domains, and formats, em-

phasizing scalability and user-friendly automation for

robust integration solutions.

Rationale: Essential for establishing interopera-

ble dataspaces, this principle ensures seamless inte-

gration of heterogeneous data. Derived from MR1,

MR2, and MR3, it supports scalability and user-

friendly automation, making diverse data comparable

through automated processes (E1).

DP2: Data Resilience Promotion: Equip the sys-

tem with mechanisms for data robustness, ensuring

reliable performance with data of varying quality lev-

els, types, and formats.

Rationale: Reflecting MR1, MR2, MR3, and

MR5, this principle ensures the artifact can handle

varying data quality. Data resilience is foundational

for maintaining reliability across different data land-

scapes (E7).

DP3: Metadata Enhancement: Implement rich

metadata and contextual information in interoper-

ability artifacts, enabling effective data use and un-

derstanding across various domains.

Rationale: Building upon MR1 and MR2, this

principle mandates rich metadata for data utility.

Services providing extended metadata and semantic

models are crucial for accurate data interpretation

(E1, E4).

DP4: Universal Design for Interoperability:

Construct interoperability artifacts with a universal

design, simplifying interactions for a broad range of

users, regardless of technical expertise.

Rationale: Corresponding with MR3 and MR5,

this principle democratizes the use of interoperability

artifacts, making them accessible to users with vary-

ing technical knowledge (E5).

DP5: Adaptive Improvement: Develop arti-

facts supporting adaptive learning through commu-

nity feedback, allowing continuous improvements and

integration of new data formats.

Rationale: Aligned with MR3 and MR4, this DP

WEBIST 2024 - 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

214

Figure 2: Overview of the dependencies of the experts, the meta-requirements and the design principles. The links between

the experts and the meta-requirements show on which interviews the meta-requirements were formulated and between the

meta-requirements and the design principles the basis for deriving the design principles from the meta-requirements.

emphasizes adaptive learning from community feed-

back, ensuring artifacts evolve with new data formats

and community insights (E1).

DP6: Automation for Scalability: Integrate a

high degree of automation in interoperability artifacts

to enhance resilience against varying data qualities

and formats, establishing a scalable framework.

Rationale: Reflecting MR2, MR3, MR4, and

MR5, automation enhances the resilience and scala-

bility of artifacts, managing complexity and fostering

future expansion (E6).

Incorporating these principles into interoperabil-

ity artifacts creates resilient, scalable, and user-

friendly dataspaces, meeting the demands of an in-

terconnected, data-driven world.

5.2 Preliminary Evaluation

We evaluated the DPs as a set, the unit of prescrip-

tive knowledge (Iivari et al., 2021), using Chandra et

al.’s (Chandra et al., 2015) framework. The DPs are

accessible, using practitioner and domain expert lan-

guage. They are important, addressing a key pillar of

the European Interoperability Framework (Commis-

sion, 2023), and provide clear guidance on developing

tools for semantic interoperability.

The novelty of providing a comprehensive set

of DPs is notable, as no publication currently ad-

dresses tools for enabling semantic interoperability

in dataspaces. The DPs are actable, offering action-

able quotes from experts, and provide guidance for

developers of interoperability tools. The argumenta-

tive evaluation suggests the DPs are sufficiently de-

fined and usable for their intended purpose.

Based on the DPs derived in this work, a software

artifact was designed in a European-funded project

in the mobility domain. This artifact simplifies and

standardizes the process of creating semantic descrip-

tions of datasets and data services. This tool is utilized

within a project family consisting of over 80 partners,

primarily from industry, but also including public sec-

tor and research partners.

Initial feedback indicates that the tool enables the

creation of meaningful descriptions more easily, al-

lowing subject matter experts and domain experts to

perform this task, which brings significant value. Fur-

ther feedback and additional tests will be collected to

enhance the tool’s effectiveness and usability.

Further feedback and additional tests will be con-

ducted to gather more insights and improve the tool’s

functionality and user experience. This iterative feed-

back loop is crucial for refining the tool and ensuring

it meets the evolving needs of the data interoperability

landscape.

Speaking the Same Language or Automated Translation? Designing Semantic Interoperability Tools for Data Spaces

215

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

In the rapidly evolving landscape of data management

and sharing, semantic interoperability is a crucial fac-

tor. Integrating different data sources, models, and

ontologies is a complex but important task.

Contributions. Our study makes a significant

contribution to semantic interoperability in datas-

paces by developing six novel DPs. These principles

integrate extensive conceptual and empirical knowl-

edge and are specifically tailored to the requirements

of automatic, scalable and resilient semantic inter-

operability. The DPs are new to semantic interop-

erability for dataspaces and the ability to translate

complex theories into practical, actionable guidelines,

thus providing significant added value for academic

research and practical application in dataspace man-

agement. The development of these principles is

based on a careful analysis of 31 professional pub-

lications and expert interviews, underlining their rel-

evance and applicability in current and future datas-

pace integration and management scenarios.

Limitations. While our research provides direc-

tional insights, some limitations need to be consid-

ered. Research on dataspaces is subject to continuous

change, which means that our findings, although cur-

rent, may require future adjustments. Furthermore,

the design principles presented are yet to be practi-

cally evaluated in terms of their effectiveness in real-

world application scenarios. The qualitative data of

our study, obtained through a focus group and expert

interviews, offer multiple perspectives but might be

shaped by the context of the participants.

Future Work. To address these limitations and

further develop our research, several avenues are

open. An immediate step is the instantiation of the

DPs into a working prototype, allowing for practical

evaluation. We are establishing a conceptual frame-

work for developing this prototype with a small devel-

oper group. Before development, an empirical eval-

uation with a broader expert group is planned to en-

sure the effectiveness and practical applicability of the

DPs, particularly focusing on their level of abstraction

and guidance for practitioners. Another critical area

of exploration is the level of integration of interoper-

ability tools within dataspaces and the extent of their

specialization. Our long-term vision is to develop a

universal tool akin to ”Translator for data models.”

However, the efficiency and feasibility of such a uni-

versal tool versus more specialized tools require fur-

ther investigation.

Conclusion. While our study makes significant

strides in the field of semantic interoperability in

dataspaces, it also opens up numerous research op-

portunities. The dynamic nature of dataspaces, the

evolving requirements of interoperability tools, and

the economic considerations of their implementation

all point towards a rich and fertile ground for future

research. Developing a practical prototype based on

our DPs, followed by empirical evaluation and eco-

nomic modeling, will be crucial steps in advancing

the field and realizing the full potential of semantic

interoperability tools in dataspaces.

REFERENCES

Ardjani, F., Bouchiha, D., and Malki, M. (2015). Ontology-

Alignment Techniques: Survey and Analysis. Inter-

national Journal of Modern Education and Computer

Science, 7(11):67–78.

Baskerville, R. L., Baiyere, A., Gregor, S. D., Hevner, A. R.,

and Rossi, M. (2018). Design science research contri-

butions: Finding a balance between artifact and the-

ory. Journal of The Association for Information Sys-

tems, 19:3.

Boukhers, Z., Lange, C., and Beyan, O. (2023). Enhanc-

ing Data Space Semantic Interoperability through Ma-

chine Learning: A Visionary Perspective. In Compan-

ion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023,

pages 1462–1467, Austin TX USA. ACM.

Chandra, Seidel, and Gregor (2015). Prescriptive Knowl-

edge in IS Research: Conceptualizing Design Princi-

ples in Terms of Materiality, Action, and Boundary

Conditions. In 2015 48th Hawaii International Con-

ference on System Sciences, pages 4039–4048, HI,

USA. IEEE.

Chandra, Seidel, and Purao (2016). Making Use of De-

sign Principles. In Parsons, J., Tuunanen, T., Ven-

able, J., Donnellan, B., Helfert, M., and Kenneally,

J., editors, Tackling Society’s Grand Challenges with

Design Science, volume 9661, pages 37–51. Springer

International Publishing, Cham.

Commission, E. (2023). The European Interoperability

Framework in detail | Joinup. https://bit.ly/3SDMRfP.

Curry, E. (2020a). Dataspaces: Fundamentals, Principles,

and Techniques, pages 45–62. Springer International

Publishing, Cham.

Curry, E. (2020b). Real-Time Linked Dataspaces: Enabling

Data Ecosystems for Intelligent Systems. Springer In-

ternational Publishing, Cham.

Curry, E., Scerri, S., and Tuikka, T., editors (2022). Data

Spaces: Design, Deployment and Future Directions.

Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Drees, H., Pretzsch, S., Heinke, B., Wang, D., and Langdon,

C. S. (2021). Data Space Mesh: Interoperability of

Mobility Data Spaces.

European Commission (2020). European data strat-

egy. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-

policy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-

age/european-data-strategy en.

WEBIST 2024 - 20th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

216

Franklin, M., Halevy, A., and Maier, D. (2005). From

databases to dataspaces: A new abstraction for in-

formation management. ACM SIGMOD Record,

34(4):27–33.

Gregor (2006). The Nature of Theory in Information Sys-

tems. MIS Quarterly, 30(3):611.

Guggenberger, T. M., Altendeitering, M., and Lang-

don Schlueter, C. (2024). Design principles for quality

scoring-coping with information asymmetry of data

products. In Proceedings of the Hawaii International

Conference on System Sciences (HICSS).

Halevy, A., Franklin, M., and Maier, D. (2006). Principles

of dataspace systems. In Proceedings of the Twenty-

Fifth ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART Symposium on

Principles of Database Systems, pages 1–9, Chicago

IL USA. ACM.

Haslhofer, B. and Klas, W. (2010). A survey of techniques

for achieving metadata interoperability. ACM Com-

puting Surveys, 42(2):1–37.

Heiler, S. (1995). Semantic interoperability.

Hevner, March, Park, and Ram (2004). Design Science

in Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly,

28(1):75.

Hutterer, A., Krumay, B., and M

¨

uhlburger, M. (2023). What

constitutes a dataspace? Conceptual clarity beyond

technical aspects. In AMCIS 2023 Proceedings.

Iivari, J., Rotvit Perlt Hansen, M., and Haj-Bolouri, A.

(2021). A proposal for minimum reusability evalua-

tion of design principles. European Journal of Infor-

mation Systems, 30(3):286–303.

Jabbar, S., Ullah, F., Khalid, S., Khan, M., and Han, K.

(2017). Semantic Interoperability in Heterogeneous

IoT Infrastructure for Healthcare. Wireless Communi-

cations and Mobile Computing, 2017:1–10.

Jones, D. and Gregor, S. (2007). The Anatomy of a Design

Theory. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 8(5):312–335.

Levy and Ellis (2006). A Systems Approach to Conduct

an Effective Literature Review in Support of Informa-

tion Systems Research. Informing Science: The In-

ternational Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline,

9:181–212.

Liu, X., Tong, Q., Liu, X., and Qin, Z. (2021). Ontology

Matching: State of the Art, Future Challenges, and

Thinking Based on Utilized Information. IEEE Ac-

cess, 9:91235–91243.

Mcadams, D. (2003). Identification and codification of prin-

ciples for functional tolerance design. Journal of En-

gineering Design, 14(3):355–375.

M

¨

oller, F., Guggenberger, T. M., and Otto, B. (2020). To-

wards a Method for Design Principle Development in

Information Systems. In Hofmann, S., M

¨

uller, O., and

Rossi, M., editors, Designing for Digital Transforma-

tion. Co-Creating Services with Citizens and Industry,

volume 12388, pages 208–220. Springer International

Publishing, Cham.

Otero-Cerdeira, L., Rodr

´

ıguez-Mart

´

ınez, F. J., and G

´

omez-

Rodr

´

ıguez, A. (2015). Ontology matching: A lit-

erature review. Expert Systems with Applications,

42(2):949–971.

Otto, B. (2022). A federated infrastructure for European

data spaces. Communications of the ACM, 65(4):44–

45.

Otto, B., Ten Hompel, M., and Wrobel, S., editors (2022).

Designing Data Spaces: The Ecosystem Approach to

Competitive Advantage. Springer International Pub-

lishing, Cham.

Ouksel, A. M. and Sheth, A. (1999). Semantic interoper-

ability in global information systems. ACM SIGMOD

Record, 28(1):5–12.

Pan, S., Luo, L., Wang, Y., Chen, C., Wang, J., and Wu, X.

(2023). Unifying Large Language Models and Knowl-

edge Graphs: A Roadmap.

Schoormann, T., Behrens, D., Fellmann, M., and Knackst-

edt, R. (2018). Design Principles for Supporting Rig-

orous Search Strategies in Literature Reviews. In 2018

IEEE 20th Conference on Business Informatics (CBI),

pages 99–108, Vienna. IEEE.

Sein, Henfridsson, Purao, Rossi, and Lindgren (2011). Ac-

tion Design Research. MIS Quarterly, 35(1):37.

Singh, M. and Jain, S. K. (2011). A Survey on Dataspace. In

Wyld, D. C., Wozniak, M., Chaki, N., Meghanathan,

N., and Nagamalai, D., editors, Advances in Network

Security and Applications, volume 196, pages 608–

621. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Theissen-Lipp, J., Kocher, M., Lange, C., Decker, S.,

Paulus, A., Pomp, A., and Curry, E. (2023). Seman-

tics in Dataspaces: Origin and Future Directions. In

Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference

2023, pages 1504–1507, Austin TX USA. ACM.

Uschold, M. and Gruninger, M. (2004). Ontologies and

semantics for seamless connectivity. ACM SIGMOD

Record, 33(4):58–64.

Vom Brocke, J., Simons, A., Riemer, K., Niehaves, B., Plat-

tfaut, R., and Cleven, A. (2015). Standing on the

Shoulders of Giants: Challenges and Recommenda-

tions of Literature Search in Information Systems Re-

search. Communications of the Association for Infor-

mation Systems, 37.

Wang, H., Liu, C., Xi, N., Qiang, Z., Zhao, S., Qin, B., and

Liu, T. (2023). HuaTuo: Tuning LLaMA Model with

Chinese Medical Knowledge.

Wang, Y., Song, S., and Chen, L. (2016). A Survey

on Accessing Dataspaces. ACM SIGMOD Record,

45(2):33–44.

Webster, J. and Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past

to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review.

MIS Quarterly, 26(2):xiii–xxiii.

Wenz, V., Kesper, A., and Taentzer, G. (2021). Detecting

Quality Problems in Data Models by Clustering Het-

erogeneous Data Values.

Zhang, H., Babar, M. A., and Tell, P. (2011). Identifying

relevant studies in software engineering. Information

and Software Technology, 53(6):625–637.

Speaking the Same Language or Automated Translation? Designing Semantic Interoperability Tools for Data Spaces

217