Designing Stemie, the Evolution of the Kid Grígora Educational

Robot

Rolando Barradas

1,2,5 a

, José Alberto Lencastre

3b

, Salviano Soares

1,2,5 c

and António Valente

1,4 d

1

School of Sciences and Technology-Engineering Department (UTAD), Portugal

2

Institute of Electronics and Informatics Engineering of Aveiro (IEETA), University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

3

CIEd - Research Centre on Education, Institute of Education, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, Braga, Portugal

4

INESC TEC, Porto, Portugal

5

Intelligent Systems Associate Laboratory (LASI), Portugal

Keywords: Robotics, Usability, STEM, Technology-Enhanced_Learning, Scratch, Mblock.

Abstract: STEM education advances at the same rate as the need for new and more evolved tools. This article introduces

the latest version of the Kid Grígora educational robot, based on the work of Barradas et al. (2019). Targeted

for students aged 8 to 18, the robot serves as an interdisciplinary teaching tool, integrated into STEM curricula.

The upgraded version corrects what we’ve learned from a real test with 177 students from a Portuguese school

and adds other features that allow this new robot to be used in even more educational STEM and problem-

solving scenarios. We focused on the creation of a second beta version of the prototype, named Stemie, and

its heuristic evaluation by three experts. After all the issues and suggestions from the experts have been

resolved and implemented, the new version is ready for usability evaluation.

1 INTRODUCTION

As STEM (science, technology, engineering, and

mathematics) education evolves, also the tools that

teachers use need to evolve. This article introduces

the next iteration of the development of the Kid

Grígora educational robot by Barradas et al. (2019).

Designed to be used by students aged from 8 to

18, this robot was meant to act as an interdisciplinary

teaching tool integrated into the curriculum of STEM

areas. Due to the importance of adaptability to

different STEM subjects, we decided to make it even

more functional pushing even further the students’

technical competencies. Together with the set of

STEM-related exercises, currently under

development, to be published in two books, aimed at

students and teachers, this new version will provide

an easier way for students to develop several skills

such as Computational Thinking and Problem

Solving and for teachers to more easily support them

in this task.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9399-9981

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7884-5957

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5862-5706

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5798-1298

2 BACKGROUND

Based on the same concepts as previously, we revisit

the concepts of computational thinking, problem-

solving skills, and Visual Programming Languages.

2.1 Computational Thinking and

Problem-Solving Skills

It’s possible to define computational thinking as a set

of processes involved in formulating a problem and

its solutions in a way that a human or machine can

effectively solve it (Wing, 2017), and it is more

closely linked to conceptualization than to the coding

process itself (Wing, 2007).

In the 21st century, children must have a range of

functional and critical thinking skills related to

information, media, and technology, and creativity,

computational thinking and problem-solving are

some of them.

Barradas, R., Lencastre, J., Soares, S. and Valente, A.

Designing Stemie, the Evolution of the Kid Grígora Educational Robot.

DOI: 10.5220/0012683500003693

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2024) - Volume 1, pages 159-169

ISBN: 978-989-758-697-2; ISSN: 2184-5026

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

159

Barradas et al. (2021) studies on computational

thinking showed some effective ways of developing

those skills and consolidated the idea that if students

must solve different types of unfamiliar problems in

creative ways it makes them think creatively and get

to better solutions. Also noted is the fact that students

were developing their problem-solving skills,

learning computer science concepts and having fun at

the same time. This type of activity makes the

knowledge constructed better comprehended and

retained (Jonassen, 2011).

2.2 Visual Programming Languages

Visual programming languages, as noticed by Silva et

al. (2015), provide higher levels of abstraction that

turn out to be very useful when a project tries to reach

a younger public. Typically with no previous

programming experience, these users/students tend to

start programming with Scratch at levels that go from

elementary school to college, and subjects as diverse

as math, computer science, language arts and social

studies (Scratch Foundation, n.d.a).

Students can use Scratch to code with blocks and

create interactive stories, animations, and even games

(Resnick et al., 2009) learning to think creatively,

reason systematically, and work collaboratively

(Scratch Foundation, n.d.b).

Designed especially for ages 8 to 16, Scratch was

made with simple grammar, and blocks with

connectors that suggest where they can be connected

(Resnick, 2012).

However, the real challenge of using Scratch for

such a project is the Blocks themselves. Every piece of

code needed to make a real robot work needs to be

implemented. Data structures in Scratch are limited to

simple variables and stacks which makes programming

a complex algorithm and interaction with external and

autonomous hardware may be a challenge.

On the other hand, the fact that in 2014, the source

code for Scratch was officially released and set

available at https://github.com/scratchfoundation,

allowed the creation of several forks and add-ons.

Some of these forks, such as mBlock, simplified the

task of communication with external hardware and it

allowed to reduce the complexity of code needed to

program a robot (Mblock.cc., 2023).

This was achieved by adding a code translator

module to the original Scratch code, that allows to

code in blocks and translate them to languages such

as C++ that the Arduino boards can be programmed

with (Figure 1). Also, the functionality to create and

add extensions to mBlock provides a higher degree of

integration with external hardware.

Figure 1: Arduino code generated by mBlock.

3 METHOD

Since the beginning, the development of the

prototype was done following an Instructional

System Design model (Clark, 2000), referred to as

ADDIE, an acronym for Analysis, Design,

Development, Implementation and Evaluation

(Figure 2). In this article, we will describe another

cycle of development namely the phases of

Implementation, Evaluation, Analysis, and Design.

The Evaluation phase is fundamental and has been

a part of the process since the beginning. It supplies

information that feeds all the cyclic processes of

design and development. It’s very useful as a part of

the spiral of analysis, design, development, and

implementation as it contributes to the continuous

improvement of the prototype (Lencastre, 2012).

Figure 2: The ADDIE Model.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

160

3.1 Implementation

In the school year of 2018/2019, we implemented a

controlled test, in a real user scenario that involved

177 students, 100 from the 5

th

grade and 77 from the

6

th

grade of a Portuguese school. In that year, 6

lessons of the ICT and programming classes of those

students were dedicated to assembling Kid Grígora

and 6 more to use it, programming with mBlock.

The students in the study belonged to 8 different

classes, 4 from each of the 5

th

and 6

th

grades of

schooling. Classes had different durations for each

year of schooling, being 150 minutes for the 5th year

and 90 minutes for the 6th year. The distribution of

the students per class is seen in Table 1. Each class

had independent lessons and the students didn’t mix

while assembling the robot.

Table 1: Distribution of students per class.

At the beginning of the test, the students were

randomly distributed in the classroom and were given

a Kid Grígora kit with all the components they

needed to assemble the robot (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Parts on the Kid Grígora kit.

The assembly instructions consisted of a set of 194

detailed photographs and 5 videos, available online,

that allowed the students to build the robot step by

step (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Sample of the assembly instructions.

At the end of the test, all students were supposed to

have built a Kid Grígora robot (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Assembled Kid Grígora.

After the assembly test, all 177 robots were collected

by the responsible teacher and carefully reviewed,

with all assembly problems noted for later analysis.

3.2 Evaluation

From the 177 students, we registered 22

(approximately 12%) that finished the assembly

without any error. Also to take note is that 12 students

(approximately 7%) were not able to finish the robot

within the determined time (Table 2).

In total, we registered 330 errors distributed by 14

different types.

Table 2: Maximum and minimum results.

School year A B C D

5th26252425

6th17162321

Number of students per class

Designing Stemie, the Evolution of the Kid Grígora Educational Robot

161

To organize the collected data, we chose to

categorize it into meaningful categories, by assigning

a label to each one of the errors found.

Using categorization, allowed us to reduce our

results from 14 types of errors to 3 different

categories, more measurable and comparable:

• Structural Errors: issues related to the design

and physical structure of the robot. In this

category, we included all problems related to

mechanical aspects, such as the lack of

components in the final assembly, the fixing

points, missing wiring, or the assembly of the

robot;

• Powering Issues: related to the power supply to

all the components of the robot. In this category,

we included problems like missing power lines

for certain components and mixing GND and

Vcc or creating any sort of short-circuit;

• GPIO (General-Purpose Input/Output) errors:

errors that are related to the connections

between the Arduino microcontroller and the

rest of the components. We included all

incorrect wiring that may cause the input or the

control signals from working.

In both grades of schooling, as shown in Tables 3 and

4, most of the detected errors fell into the Powering

Issues category.

Table 3: Summary of detected errors for 5

th

-grade students.

As expected, the older students assembled the robots

with a lower average of errors per student, although

not much different.

Table 4: Summary of detected errors for 6

th

-grade students.

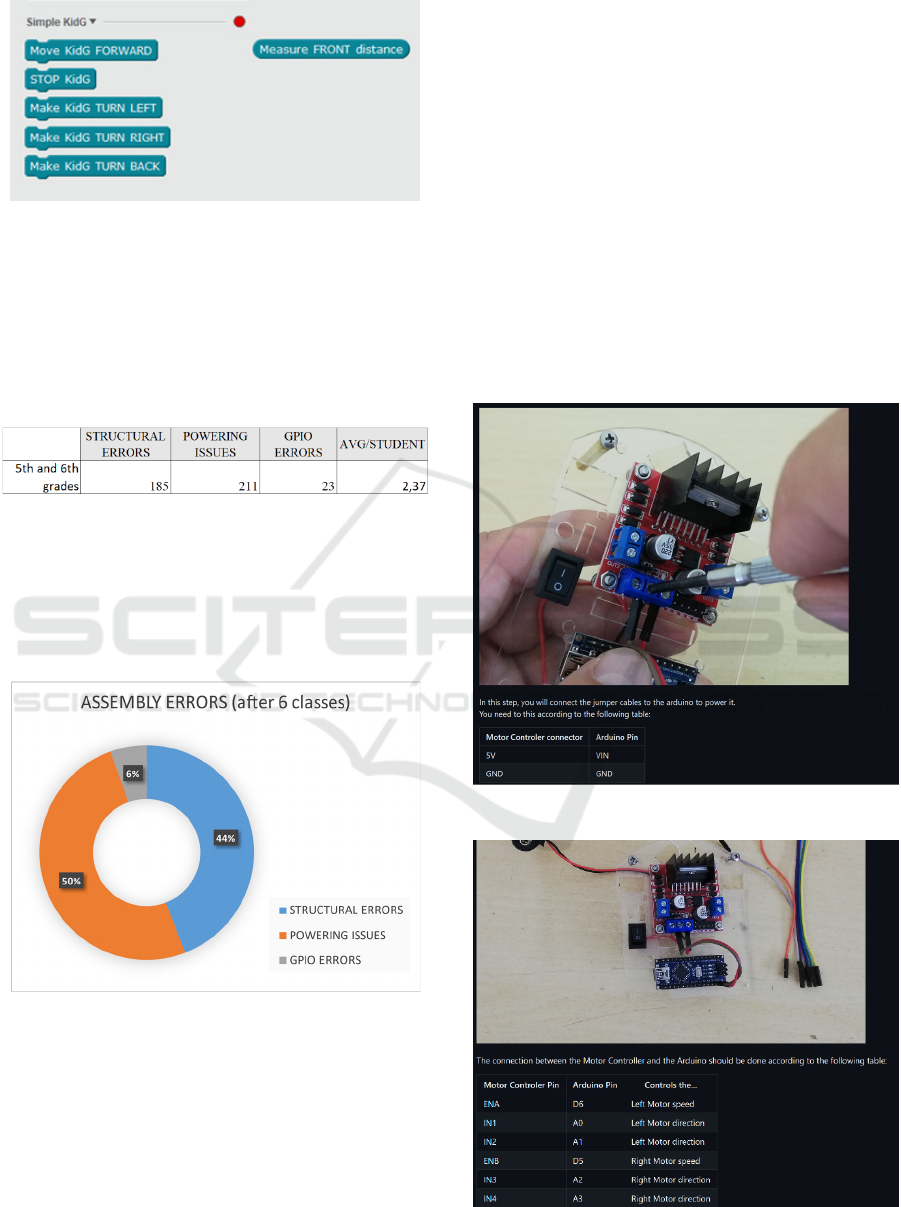

To better compare the results of both grades of

schooling, we normalized the data. The results of the

normalization can be analysed in Figure 6 and show

that older students ended up making more mistakes in

terms of structural errors than the younger ones.

However, in terms of wiring the components, the 6

th

graders had a better performance than the 5

th

graders,

with fewer errors in the Powering Issues category.

Figure 6: Normalized data comparison of assembly errors

between 5

th

and 6

th

graders.

In terms of percentage, the distribution of errors is

shown in Figure 7, with the category Powering Issues

being the one in which the most errors were detected

(61%). This very relevant information showed us that,

at least for this age range, the information present in

the assembly instructions needs to be more detailed in

terms of powering all the components of the robot.

Figure 7: Pie chart of assembly errors.

Overall the results were very good, especially

considering the age range of the students, with a

global average of errors per student of 1,86.

In the second part of the testing, during 6 lessons,

the same students used a simple framework,

developed in mBlock (Figure 8) to program their

robots in simple forward, backwards and turn

movements, while reasoning to make their robots

move and turn as straight as possible. In this part of

the test, only the students who completed the robot in

the previous task were involved.

# STUDENTS

STRUCTURAL

ERRORS

POWERING

ISSUES

GPIO

ERRORS

AVG/STUDENT

100 55 123 13 1,91

# STUDENTS

STRUCTURAL

ERRORS

POWERING

ISSUES

GPIO

ERRORS

AVG/STUDENT

77 51 78 10 1,81

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

162

Figure 8: Extension developed for mBlock

After the 6 lessons, that functioned as a small stress

test for the hardware, all the robots were rechecked,

and the new problems were added to the initial results

table and shown in Table 5.

Table 5: Summary of detected errors after assembly and

stress test.

This new table shows that there was an increase in

both Powering and Structural issues. However, in

terms of Powering, the increase is around 5% while

in terms of Structural Errors, the increase was about

75% as seen in Figure 9. This fact also increased the

average of errors from 1,86 to 2,37 per student. In

terms of GPIO, there was no new record of errors.

Figure 9: Updated Pie chart of detected assembly errors,

after 6 classes stress test.

3.3 Analysis and Design Enhancements

The results after the 12 classes for assembly and stress

use showed that the platform, although usable, needed

some improvements in both Powering instructions

and in terms of Structure.

It is possible to perceive from Barradas et al.

(2019) that Kid Grígora’s simple structure was held

together by M3 screws and hex screw nut. Also, the 3

front sensors were held to the main platforms by

velcro tape. Although in the usability tests, there were

no problems reported related to those components,

what happens is that after some use, the hex screw

nuts tend to get loose if not tightened well, and the

structure was shaken. This fact caused almost every

occurrence of errors in the structure, post-assembly.

In terms of Powering issues, they were related to

faulty batteries and bad soldering, not detected on the

first inspection.

As we previously mentioned, to try to solve the

Powering issues, we decided to create more detailed

assembly instructions, using the same type of pictures

but adding detailed text and tables with information

on where to connect each of the jumper cables in the

robot. (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Updated assembly instructions.

Figure 11: L298N connection to Arduino Nano.

Designing Stemie, the Evolution of the Kid Grígora Educational Robot

163

Although there were not many errors in terms of

GPIO, we decided that the new instructions should

also have a table with every IO pin used in Arduino

(Figure 11).

To cope with structural problems, we decided to

change the structure holding points and don’t use the

M3 screws anymore, as we concluded that, for

children of this age, that wasn’t the best solution.

After browsing the market for solutions, we chose to

use M3 brass female spacers instead.

3.3.1 Upgraded Hardware Components

Remembering that we were creating an educational

tool, the decision to upgrade the hardware came from

the idea of enhancing the educational impact of our

robot. As we were making changes, we decided to

create a more versatile platform with other types of

sensors and actuators. This should allow both

students and teachers to use it, integrated with more

scientific and technological subjects. Increasing

problem-solving scenarios enables students to engage

in more challenges across multiple STEM subjects

and not only Robotics.

After meeting with teachers from STEM subjects

such as Sciences, Physical Chemistry and Maths, the

changes in Table 6 were made:

Table 6: Comparison of changed components.

Old version Upgraded version

3 Ultrasonic sensors 1 Ultrasonic Sensor

1 Green LED 1 RGB LED

- 3 Infrared line sensor

M3 screws M3 brass female spacers

Velcro Tape Nano PU Gel Tape

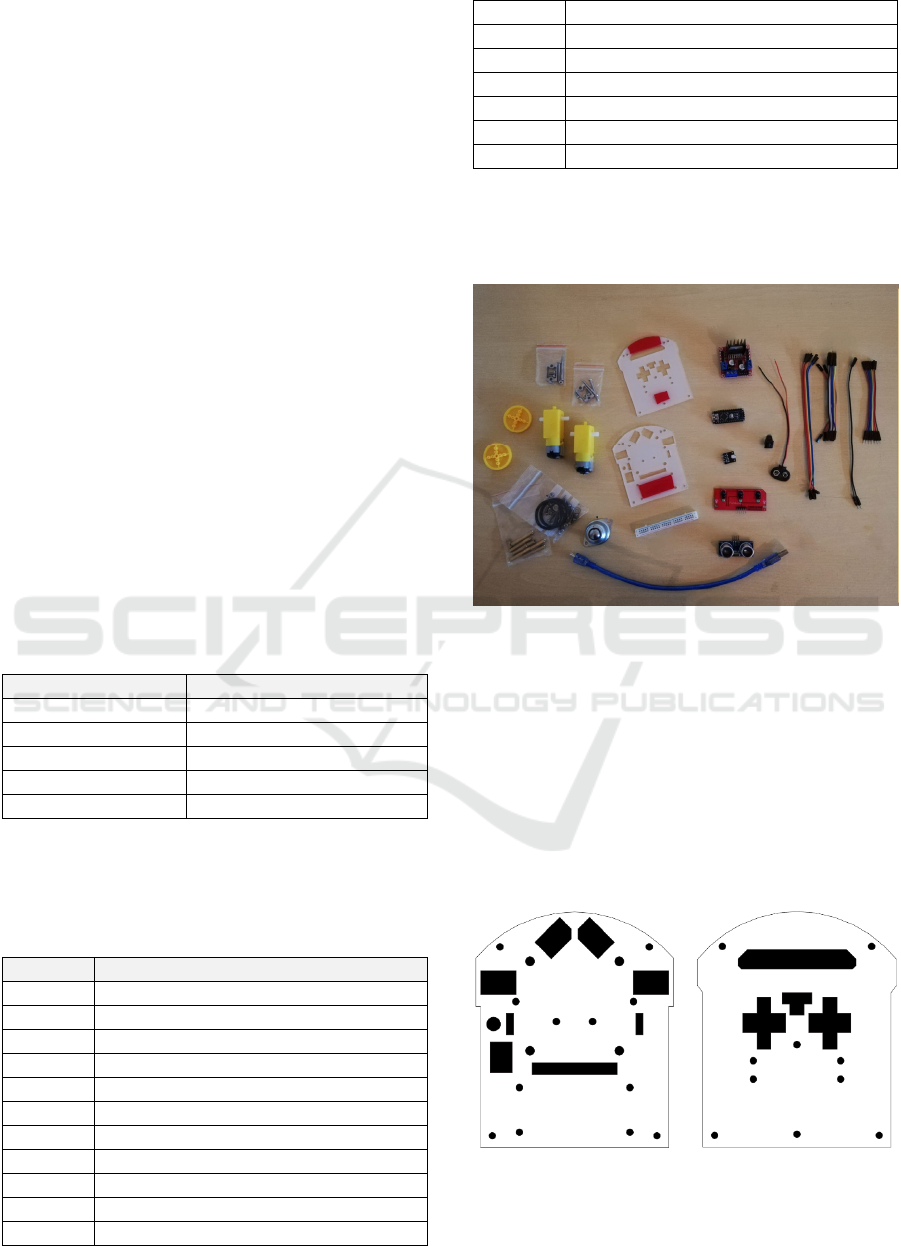

Due to these changes, the list of components of the

upgraded version of our robot is the one in Table 7

and Figure 12.

Table 7: List of components of Upgraded Version.

Quantity Component

1 Arduino Nano

2 Geared DC Motor

1 3-channel infrared tracking module

1 HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Sensor

1 L298N DC Motor Driver

1 RGB LED module

1 9v Battery Holder Clip

1 Mini ON-OFF Switch

1 Mini Breadboard

1 USB cable

35 Jumper cables (10/20 cm, M-F & F-F)

1 Caster Ball

2 Plastic Wheels

4 Spacer M3 10mm

4 Spacer M3 30mm

2 Motor Bracket Holder (with screws)

2 Acrylic Platform 3mm

2 O-Ring

The upgraded version would still be controlled by an

Arduino Nano, as this small microcontroller proved

to be very reliable and its small form factor is very

important for this project.

Figure 12: Components of the upgraded version.

Due to these small, but important, changes, the main

platforms had to be slightly modified to accommodate

the new components. The initial idea from Barradas

et al. (2019), was to use 3D printed platforms for the

robot. The robots used in the test we described

already used acrylic laser cut platforms, much more

inexpensive than the 3D printed version. For this

upgraded version we opted to maintain the acrylic

version but also have the option to use laser-cut MDF

(Figure 13).

Figure 13: New design of the platforms.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

164

These new platforms were made specifically for the

two planned versions of our robot. The top platform,

with specific holes for signal and power wires that

connect to Arduino, holes for motor current wires, a

specific one to place a power switch, and another one

for the LED. As for the lower platform, there are

specific rounded holes to attach the motor bracket

holders and the Caster ball, as well as wholes for the

jumper cables to go through to the breadboard and

components like the 3-channel infrared tracking

module and the HC-SR04 Ultrasonic Sensor. Both

platforms also have round 3mm holes to attach the

brass spacers that will join the two platforms and give

the robot stability. The design of these platforms also

reflects the changes needed for the future upgraded

version of Kid Grígora Semi-Pro, not the object of

this article.

3.3.2 Programming Interfaces

The main idea about the programming interfaces used

in Kid Grígora remains in this upgraded version: to

build a programming framework, simple enough to be

used by small children, allowing them to explore the

full potential of the robot.

However, due to the new features added, as the

new components demand new programming

functions, we had to develop a different set of

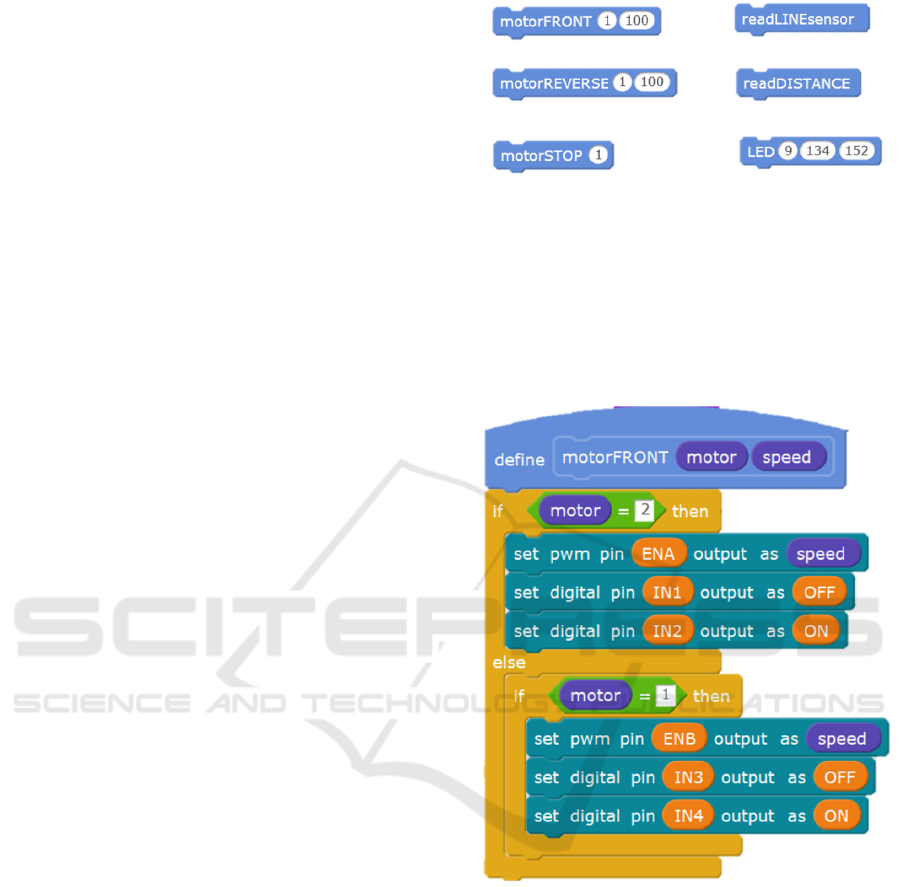

commands. Looking at Figure 14, it is possible to

perceive some differences in the developed

framework for this version. We decided to use a

terminology where the two engines can be controlled

separately and with different speeds. To do so, we

created a motorFRONT procedure that moves the

motors forward and allows us to change the speed of

each of them, by using it with its number (motor 1,

Right side, or 2, Left side). Following the same idea,

we created a motorREVERSE procedure that moves

the motors backwards, and a motorSTOP that stops

each motor. Combining these blocks you can control

both motors, each one of them independently,

allowing the students to create their own set of

movements. In terms of using the sensors, we created

a readDISTANCE procedure that allows easy use of

the ultrasonic sensor and a readLINEsensor

procedure that reads the floor under the sensor to try

to find out whether there is a white or black line to

follow. To allow an easy way to use the RGB LED,

we created a LED procedure, fed with the RGB values

of the colour you want to display on the LED.

Figure 14: Programming framework.

The framework was built in a way that the teachers

and more advanced students could analyse all the

details of the programming. Instead of creating a

black box with impossible-to-analyse functions, we

created simple procedures in mBlock, leaving all the

code visible for them to study and change if needed

(Figure 15).

Figure 15: Procedure motorFRONT.

3.3.3 Add-on Features

More than to develop a robot, we wanted to create

something that children could relate to and would like

to use and learn about.

To make the robot more attractive to children, we

decided to create some add-ons to allow

personalization. Using personalization, we expect to

create a sense of ownership and identity so that

children should become more attached to the robot.

Personalization also allows them to express their

creativity in aspects such as choosing colours,

accessories, or even other design features.

Designing Stemie, the Evolution of the Kid Grígora Educational Robot

165

To easily allow personalization, we developed a set

of 3d printed parts, that can also be replicated in

cardboard, in case there is no 3d printer available.

One of the 3d printed parts is a mask adapter (Figure

16). It’s a part that can be attached to the front of the

robot, holding onto the brass spacers. With holes for

the Ultrasonic sensor, this 3d printable part allows

children to build a mask and attach it to the robot.

Figure 16: 3D printable mask adapter.

In the case of younger children who could find it hard

to build their masks, we also created some 3D

printable add-on masks just for the children to paint.

These masks attach to the mask adapter and children

could choose from a set of different characters

(Figure 17).

Figure 17: 3D printable masks.

Also in the add-on category, and with the idea of

adding some extra features to our robot, we developed

an App for Android, with which children can control

their robots by phone.

After uploading a specially designed firmware to

the Arduino and connecting an HC-05 Bluetooth

module, it is possible to use the app to control the

movements and some other features of the robot. The

development of firmware was done in mBlock, to

maintain the coherence with the rest of the code and the

Stemie ControlApp (Figure 18) was developed in MIT

(Massachusetts Institute of Technology) AppInventor

a visual programming environment, Blocks-based, to

create Android Apps, developed by the MIT.

Figure 18: Screenshot of the Stemie ControlApp.

3.4 Development

Building upon the concepts and the prototype by

Barradas et al. (2019), the original idea of Kid

Grígora was to have an educational robot that could

be used as a teaching tool to be integrated into the

curriculum. Also, a secondary objective was that it

had to be designed small enough to allow children to

use it in the Micromouse Portuguese Contest.

All the changes we made in this upgraded version led

to a robot that, in its base version, is not capable of

participating in that competition, but that’s more

usable in general, in STEM areas. Because of that,

from now on, it will be known as Stemie (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Stemie the robot.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

166

3.4.1 Building the Second Beta Version

Stemie was built upon Kid Grígora’s foundations,

with a different design but simpler and faster to build.

After its construction, it was then, subjected to a

test in a heuristic evaluation by experts. This

evaluation had the objective of appraising both

usability and potential design problems and gathering

suggestions from the experts on how to solve the

problems they found and, possibly, add new features.

To test the prototype, we chose double experts

(Nielsen, 1993) experienced not only in usability but

also with specific expertise in robotics as they

potentially find 1.5 times more problems than simple

usability specialists (Nielsen, 1993). We used three

ICT and Robotics teachers from 3 different countries

(Italy, Lithuania and Croatia).

The evaluations were carried out according to

each expert’s agenda and started with an explanation

of the expected use of Stemie by end-users, as a

STEM tool. The evaluators had knowledge of the

previous version and had previously been given the

new robot’s parts and the updated assembly

instructions, and were asked to assemble it.

After the tests, each expert was asked to fill out a

heuristic evaluation questionnaire to report possible

problems, by using Nielsen’s severity rating scale

(Nielsen, 1993). In this scale, they used numbers from

0 to 4 in which 0 means "I don’t agree that this is a

usability problem at all" and 4 means a "Usability

catastrophe: imperative to fix this before the product

can be released".

About the strong points of the heuristic

evaluation, all the experts mentioned the evolution in

structure stability, using brass spacers instead of

screws and hex nuts and that the robot should be even

easier to build now. Although like in Kid Grígora’s

evaluation, all the experts said that it was a good idea

to use standard electronic components, easy to find

and replace, in case of malfunction. Also mentioned

was the large number of problem-solving tasks that it

is possible to solve using Stemie. Two of the experts

mentioned the fact that the instructions were very

detailed on both the electrical connections and the

GPIO pins, which would make it easier for children

to assemble the robot.

The weakest points in the heuristic evaluation

(ratings 3 and 4) are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8: Severe and catastrophic errors found, according to

Nielsen’s heuristics.

Nielsen’s heuristics

Interface (IN) Degree

IN1 Visibility of system status 3

IN5 Error prevention 4

Regarding IN1, one of the experts mentioned, that

although Stemie had an LED to visibly show the

system status, it would be more useful if it also had

audible status. Related to IN5, all of the experts stated

that there was an error in the connection of pin A6 to

the 3-channel infrared tracking module, as A6 and A7

on an Arduino Nano are pure analogue pins and

cannot be used as digital pins. Only A0-A5 can be

used as digital pins in that build of Arduino.

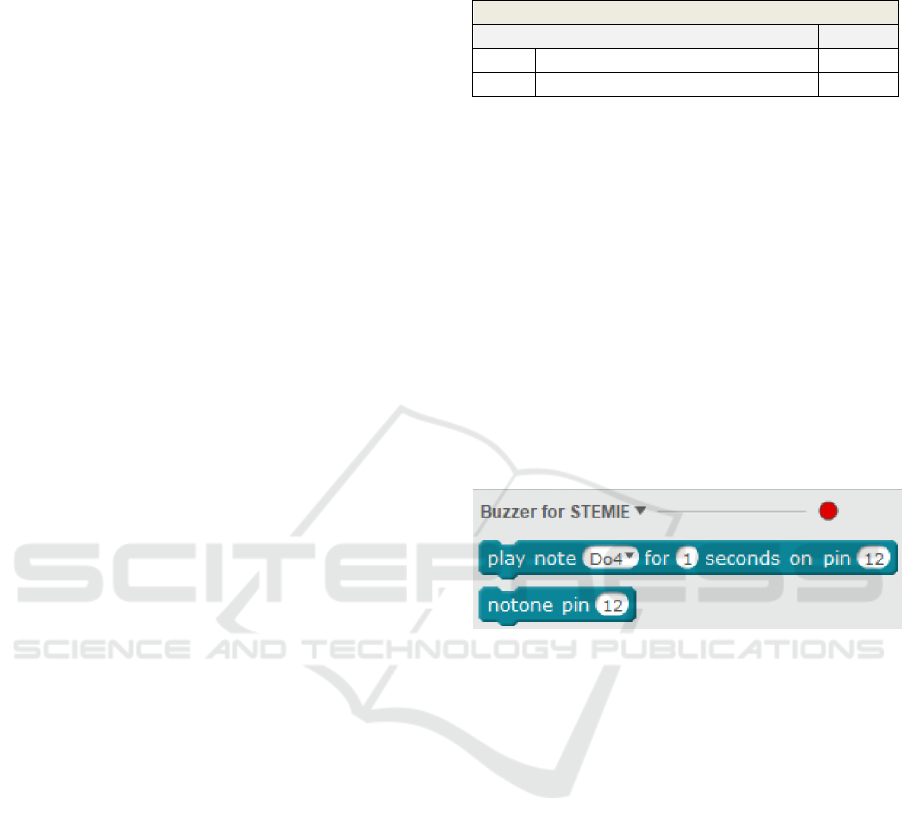

The results of the heuristics analysis led to some

changes in the final product. Regarding IN1, we

decided to add a Buzzer module to the parts list, add

a new chapter to the Assembly instructions and create

a mBlock extension (Figure 20) to allow the Buzzer

to be used as a musical instrument, allowing even

more activities to be done with Stemie.

Figure 20: Buzzer for Stemie extension.

Using the mBlock platform that allows users to write

custom extensions programmed in JavaScript, in a

way to add new functionalities to the programming

environment, we created two new blocks to be used

by students. The extension is made by two essential

parts: the definition of the block that shows in the

mBlock application and the translation to C++ code

which can be uploaded to the Arduino Nano for

execution. The following is an example of the code:

"extensionName": "Buzzer for

STEMIE",

"description": "An extension for

using a Buzzer with STEMIE",

"version": "1.5",

"author": "",

"homepage": "",

"sort":0,

"javascriptURL":"js/buzzer.js",

"firmware":"1.0",

"extensionPort":0,

"blockSpecs": [

[

"w",

Designing Stemie, the Evolution of the Kid Grígora Educational Robot

167

"play note %d.notes for %n seconds

on pin %n",

"tone",

"Do4", "1", "12",

{

"setup":"pinMode({2},OUTPUT);\n",

"inc":"",

"def":"",

"work":"tone({2},{0}, {1}*1000); //

write to buzzer\ndelay({1}*1000);",

"loop":""

}

],

[

"w",

"notone pin %n",

"notone",

"12",

{

"setup":"pinMode({0},OUTPUT);\n",

"inc":"",

"def":"",

"work":"noTone({0});\n",

"loop":""

}

]

]

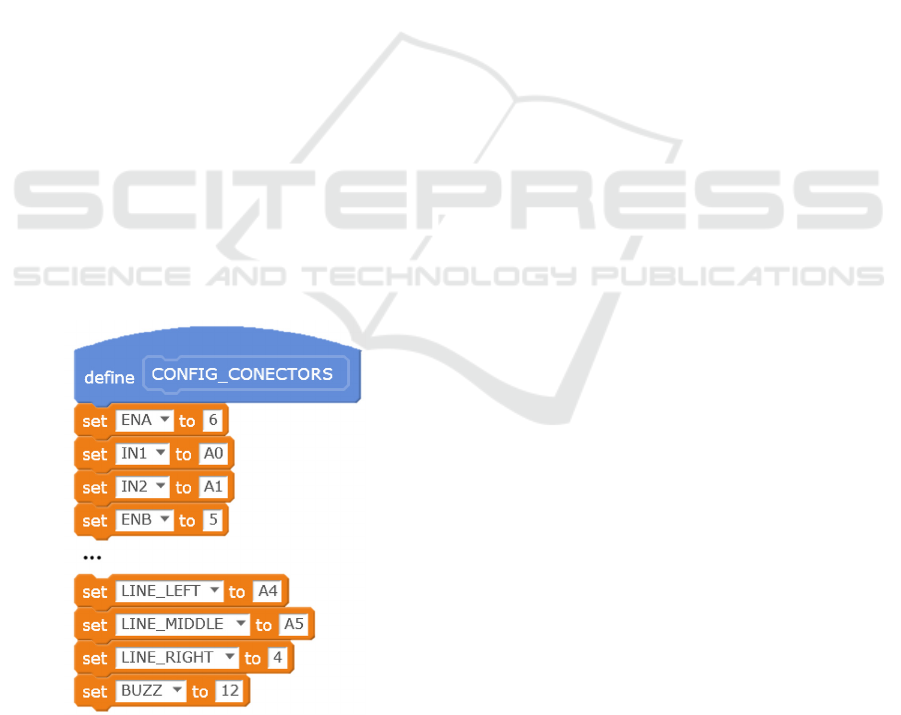

To solve IN5, we changed the assembly instructions,

moved the connection from pin A6 to pin D4, and

made some changes in the programming framework

to reflect those changes. To make it even easier to

perform such changes in the future, we added to the

Framework a procedure where all the GPIO pins can

be configured by the final user (Figure 21).

Figure 21: Excerpt from the config_connectors procedure.

7 CONCLUSIONS

Built upon Kid Grígora, Stemie marks a significant

evolution on our educational robotics platform,

aligning it with the requirements of STEM education.

The comprehensive testing we’ve done with 177

students from a Portuguese School led to some

valuable insights on assembly errors and showed us

how important it was to have even more detailed

instructions, especially due to the age range of our

end-users. Following the ADDIE model, we

analysed, implemented and evaluated, and from the

collected information we addressed both structural

and powering errors found by the end users.

After the test and further analysis, we upgraded some

of the hardware in the robot which allows students to

explore even more scientific experiments, promoting

computational thinking and problem-solving skills in

even more STEM subjects. The heuristic evaluation

by STEM experts provided even more feedback on

the design and allowed the correction of some errors.

As STEM education evolves, it’s up to us to create

tools that allow children to learn while playing.

8 FUTURE WORK

Future work includes usability tests with

representative end-users and a real stress test. It also

includes the full development of Stemie,

complemented with STEM exercises to use in

educational environments. Stemie’s Extended

edition, for older students, equipped with different

sensors and actuators, will also be a focus, aligning

our work with the original idea of participation in the

Micromouse Contest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partially funded by FCT-Fundação

para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) I.P., through

national funds, within the scope of the

UIDB/00127/2020 project (IEETA/UA,

http://www.ieeta.pt/ (accessed on March 2nd 2024)),

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00127/2020,

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDP/00127/2020

This work is partially funded by CIEd – Research

Centre on Education, Institute of Education,

University of Minho, projects UIDB/01661/2020 and

UIDP/01661/2020, through national funds of

FCT/MCTES-PT.

CSEDU 2024 - 16th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

168

We want to thank Colégio Paulo VI (Gondomar,

Portugal), and the students of the 5th and 6

th

school

years, for their collaboration and the authorisation to

perform this research on their premises.

REFERENCES

Barradas, R., Lencastre, J. A., Soares, S., & Valente, A.

(2019). Usability evaluation of an educational robot for

STEM areas. In H. Lane et al. (ed) Proceedings of the

11th International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU2019), Volume 2 (pp. 218-225).

Heraklion, Crete, GR: SCITEPRESS – Science and

Technology Publications.

Barradas, R., Lencastre, J. A., Soares, S., Valente, A., 2021.

The code.org Platform in the developing of

Computational Thinking with elementary school

students. In: H. Lane et al. (Eds) Computer Supported

Education. Csedu 2020. Communications In Computer

And Information Science, Vol 1473. Springer, Cham.

https://Doi.Org/10.1007/978-3-030-86439-2_7

Jonassen, D., 2011. Learning to solve problems. A

Handbook for Designing Problem-Solving Learning

Environments. Routledge.

Lencastre, J. A., 2012. Educação on-line: análise e

estratégia para criação de um protótipo. In J. B.

Bottentuit Junior et al. (org.), Educação on-line:

Conceitos, metodologias, ferramentas e aplicações (pp.

127-136). Editora CRV.

Mblock.cc. (2023). [online] Available at:

http://www.mblock.cc [Accessed 16 Jan. 2024].

Nielsen, J., 1993. Usability Engineering. Morgan

Kaufmann.

Resnick, M., Maloney, J., Monroy-Hernandez, A., Rusk,

N., Eastmond, E., Brennan, K., Kafai, Y., 2009.

Scratch: Programming for All. Communications of the

ACM, 52, 60-67.

Resnick, M., 2012. Reviving Papert's Dream. Educational

Technology, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 42-46.

Scratch Foundation. (n.d.a). [online] Scratch - About.

Available at: https://scratch.mit.edu/about [Accessed

16 Jan. 2024].

Scratch Foundation. (n.d.b). [online] Scratch for Educators.

Available at: https://scratch.mit.edu/educators

[Accessed 16 Jan. 2024].

Silva, S., Soares, S., Valente, A., Barradas, R. Bartolomeu,

P., 2015. Enhancing STEM courses through a robotic

innovative project. Proceedings of the 3rd International

Conference on Technological Ecosystems for

Enhancing Multiculturality - TEEM ’15, Porto,

Portugal. doi: 10.1145/2808580.2808668

Wing, J. M., 2007: Computational Thinking. Retrieved on

2019/05/01, from https://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/usr/

wing/www/Computational_Thinking.pdf.

Wing, J. M., 2017. Computational thinking’s influence on

research and education for all. Italian Journal of

Educational Technology, 25(2), 7-14. doi: 10.17471/24

99-4324/922

Designing Stemie, the Evolution of the Kid Grígora Educational Robot

169