Use of a Digital Positioning and Categorisation Aid for Clinical

Investigations on Medical Devices: Questioning the Complexity of the

Field and Harmonizing Stakeholders' Understanding

Jean-Baptiste Pretalli

1a

, Stéphanie Py

1

, Fatimata Seydou Sall

1b

, Magali Nicolier

1

,

Karine Charrière

1c

, Thierry Chevallier

2,4,5 d

and Thomas Lihoreau

1,2,3 e

1

Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Besançon, Centre d'Investigation Clinique, INSERM CIC 1431, 25030,

Besançon, France

2

Tech4Health network - FCRIN, France

3

Université de Franche-Comté, SINERGIES, F-25000 Besançon, France

4

Department of Biostatistics, Clinical Epidemiology, Public Health, and Innovation in Methodology,

CHU of Nimes, University of Montpellier, Nimes, France

5

Desbrest Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health UMR, INSERM - University of Montpellier, Montpellier, France

kcharriere@chu-besancon.fr, thierry.chevallier@chu-nimes.fr, tlihoreau@chu-besancon.fr

Keywords: Medical Devices, Clinical Research, Regulation.

Abstract: Medical devices must comply with the safety and performance requirements of the European Medical Device

Regulation. For clinical investigations, regulatory approval from competent authorities is required.

ICTROUVE is a digital tool designed to help identify the clinical investigation’s category when applying to

the French competent authority, the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des produits de santé

(ANSM). We aimed to evaluate ICTROUVE and to prepare a larger-scale study.

This pilot study was divided in two sequences. The aim of the first was to recruit experts and to collect study

synopses for which the clinical investigation’s category issued by the ANSM was known. To achieve this

aim, we created and sent a questionnaire to researchers and regulatory managers via the Tech4Health network.

During the second sequence, the experts had to read the synopses and assign them a clinical investigation’s

category, first without and then with the help of ICTROUVE. A satisfaction questionnaire was then

completed.

We found a low decision agreement between experts and ANSM (39% without ICTROUVE, 51.7% with).

ICTROUVE was perceived as useful, easy and quick to use. Information was gathered to facilitate a larger-

scale evaluation, notably on the collection of synopses and the search for experts..

1 INTRODUCTION

Medical devices (MDs) offer a wide range of

innovative healthcare solutions. They enable

pathological conditions to be diagnosed, monitored,

treated or alleviated. They influence patient longevity

and quality of life while relieving pressure on the

healthcare system (‘Medical Devices Must Be

Carefully Validated’, 2018).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1035-3566

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8351-0406

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4542-8003

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5110-6273

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8417-6609

Clinical investigation are related to medical

devices and fall within the scope of the European

Regulation 2017/745 (MDR) (HAS, 2017;

Regulation (UE) 2017/745, 2017).

The MDR brings many necessary advances but it

also implies a significant increase in the requirements

expected from manufacturers and from notified

bodies which must adapt to the new regulations. This

has a major impact in terms of cost and time that

864

Pretalli, J., Py, S., Sall, F., Nicolier, M., Charrière, K., Chevallier, T. and Lihoreau, T.

Use of a Digital Positioning and Categorisation Aid for Clinical Investigations on Medical Devices: Questioning the Complexity of the Field and Harmonizing Stakeholders’ Understanding.

DOI: 10.5220/0012617600003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 1, pages 864-871

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

could be difficult to absorb for manufacturers,

especially small and medium-sized enterprises, which

account for 95% of the total (SNITEM, 2020), and

those with a portfolio of old, low-risk products

(SNITEM, 2022). Shortages are also envisaged in

hospitals (Académie nationale de médecine, 2022;

Sayin et al., 2022). Conversely, any reduction in time

expended can confer a competitive edge upon a

manufacturer in relation to its competitors.

In France, to conduct a clinical investigation (CI)

on medical devices, authorisation from the Agence

nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits

de santé (ANSM) is essential. However, the

acceptance rate in the first round is very low. A study

of the 284 dossiers submitted for CI between May 26,

2021, and February 28, 2022, found that only 30

(10.5%) had been accepted outright. In addition, 34

(12%) dossiers for which ANSM had requested

additional information were not resubmitted by the

manufacturers (ANSM, 2022). Identifying the CI

category and compiling the application for

authorisation appear thus to be a complex task. Any

time-saving assistance would clearly be beneficial to

patients and manufacturers alike.

There are several reasons why identifying the

right CI category is so difficult. First, not every

research using an MD fall under the scope of the

MDR. Research using an MD but with a main

objective not related to the evaluation of its safety,

performance and/or effectiveness may fall under the

scope of the French Loi Jardè n°2012-300. This law

concerns all Research Involving the Human Person

(RIPH in French) with a view to furthering biological

or medical knowledge. The approach is based on risk

in three types of study. RIPH category 1 is a research

implying an intervention on the patient which is not

justified by their usual treatment. RIPH category 2

concerns interventional research with minor

obligations and risk. RIPH category 3 concerns

observational research.

Moreover, for research falling under the scope of

the MDR, seven CI’s categories exist. The number of

decision nodes required to identify the correct one is

very large, and the definitions of CI categories are

very close to each other. In addition, the definitions

are difficult to interpret. Finally, if the personnel

responsible for identifying CI categories are

qualified, they may be insufficient in number to cope

with the required workload (SNITEM, 2020).

Category 1 and 2 (CI1 and CI2) concerns clinical

investigations on a MD when CE conformity is

sought. CI3 concerns a CE-marked DM used in its

intended purpose with any additional

burdensome/invasive procedure. CI4.1 concerns a

CE-marked DM used in its intended purpose with no

additional burdensome/invasive procedure. CI4.2

concerns a CE-marked MD (any class), used in its

intended purpose without the conformity assessment

and including additional procedures. CI4.3 concerns

a CE-marked MD (of any class) used outside its

intended purpose without the purpose of CE marking

or conformity assessment. CI4.4 concerns non-CE-

marked MD (all classes) without a CE marking

objective.

ICTROUVE is a digital tool designed to help

identify the CI’s category to which an MD must be

subjected. It is a questionnaire produced online, based

on the requirements of the MDR and the adaptations

made at national level by the ANSM (Chevallier et

al.). This tool could save a considerable amount of

time in CI authorisation applications. It could also

facilitate a more relevant orientation of the

investigations and offer a way for developers and

evaluators to question their project strategy before

submission.

ICTROUVE's efficiency in correctly identifying

CI categories compared with the standard method (i.e.

as the experts usually do, without ICTROUVE) needs

to be evaluated. It means testing the concordance

between the CI categories identified with

ICTROUVE and the CI categories identified by

ANSM. This involves collecting a sufficient number

of use cases for which ANSM has issued an opinion.

It also implies the participation of a sufficient number

of representative experts to carry out the various tests.

The aim of this pilot work was to initiate this

evaluation. We present the results of a survey testing

the methods for collecting the use cases and recruiting

the experts. Another objective of the survey was to

obtain feedback on the use of ICTROUVE by

researchers and regulatory managers, and thus to

identify possible improvements to be made to

ICTROUVE. We also intended to obtain an initial

assessment of ICTROUVE's ability to identify the CI

category.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Study Design

Survey using a questionnaire and interviews.

2.2 Objectives and Outcomes

The main objective was to prepare a large-scale

evaluation of ICTROUVE's ability to correctly

identify CI categories.

Use of a Digital Positioning and Categorisation Aid for Clinical Investigations on Medical Devices: Questioning the Complexity of the Field

and Harmonizing Stakeholders’ Understanding

865

Secondary objectives were to:

1. obtain information on the actual working

methods of the experts responsible for

identifying CI categories in French

university hospitals;

2. describe the need for assistance in

identifying CI’s categories;

3. evaluate the use case identification and

collection method used to evaluate

ICTROUVE;

4. appraise the method used to identify and

invite potential experts to participate in the

ICTROUVE evaluation;

5. assess the expert’s capacity to recognise a

clinical investigation compared to a

‘classical’ RIPH study (studies involving

human subjects);

6. compare the performance of ICTROUVE

with that of the standard method for

identifying the correct CI category;

7. evaluate ICTROUVE usability in terms of

ease of use, clarity of questions and user

satisfaction;

8. obtain suggestions for improving

ICTROUVE by questioning the experts

taking part in the study;

9. describe potential failures in the use of

ICTROUVE in order to implement

corrective measures.

For secondary objectives 1, 2, 7 and 8,

assessments were carried out using Likert scales

completed at the end of the test series. Likert scales

consisted of propositions for which the respondent

expressed a degree of agreement or disagreement

(‘strongly disagree’, ‘somewhat agree’, ‘neither agree

nor disagree’, ‘somewhat agree’, ‘strongly agree’).

For secondary objective 9, potential ICTROUVE

failures were characterised by the inability to

complete all the questions and arriving at a usable

result.

2.3 ICTROUVE

ICTROUVE is a free online application developed

under REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture)

by Louise Bastide, Hugo Potier and Thierry

Chevallier of Nîmes’ University Hospital.

2.4 Study Population

Firstly, a questionnaire was sent to researchers and

regulatory managers in several French university

hospitals (via the Tech4Health network). The purpose

of this questionnaire was to assess the usefulness of a

tool to help identify CI categories, to recruit experts

and to collect use cases for the second phase of the

study.

‘Phase 2’ was carried out on volunteers referred

to in this report as ‘experts’. The set of use cases was

presented to all participants in the same order

(random order). Experts had to classify the use cases

collected in phase 1 in ‘CI’ or ‘RIPH’. Then, the

experts identified the RIPH category (RIPH 1, 2 or 3)

or the CI category (CI1, CI2, CI3, CI4.1, CI4.2, CI4.3

or CI4.4) first without ICTROUVE, then with

ICTROUVE. Finally, each participant completed a

questionnaire on usability, ease of use and

satisfaction with ICTROUVE.

The category identified by ANSM remained

secret until the end of the evaluation.

2.5 Statistical Analyses

A description of all participants was drawn up for the

following parameters: profession, number of years'

experience, and workplaces.

Categorical variables were presented in the form

of numbers and percentages. They were compared

using the Chi2 test or Fisher's exact test.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Identification and Collection of the

Use Cases

Seven use cases were collected. Three concerned

RIPH studies and 4 CI studies. For each, we had the

study category issued by the ANSM. They were

obtained from four University Hospital Centres.

3.2 Identification and Invitation of the

Experts

Twelve people replied to our contact e-mail. Nine

agreed to take part as experts: 4 researchers and 5

regulatory managers. All worked at Besançon

University Hospital, except for experts 7 (researcher)

and 9 (regulatory manager), who worked at Nancy

University Hospital.

Seven (78%) had at least 10 years of experience

in their positions, while 2 (22%) had between 1 and 5

years of experience. None had used ICTROUVE

prior to this study. Table 1 presents these experts.

ClinMed 2024 - Special Session on European Regulations for Medical Devices: What Are the Lessons Learned after 1 Year of

Implementation?

866

Table 1: Experts’ participating in study phase 2.

Regulatory

managers

n=5 (55%)

Researchers

n=4 (45%)

Total

n=9

(100%)

Years of

ex

p

erience

>10 years 4 (80%) 3 (75%) 7 (78%)

1 to 5 years 1 (20%) 1 (25%) 2 (22%)

University

Hos

p

ital

Besançon 4 (80%) 3 (75%) 7 (78%)

Nancy 1 (20%) 1 (25%) 2 (22%)

When you have to identify a CI's category, do you

usually work :

- alone? 0 (0%) 1 (25%) 1 (11%)

- in a group? 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

- alone and then

in a group?

4 (80%) 3 (75%) 7 (78%)

- alone, then in a

group for

difficult cases?

1 (20%) 0 (0%) 1 (11%)

3.3 Results Regarding the Need for

Assistance in Identifying CI

Categories

The need for help was unanimously reported (table

2).

Table 2: “Do you think a tool to help you identify the

clinical investigation category of a medical device would be

useful?”

Regulatory

manager

n=8 (67%)

Researchers

n=4 (33%)

Total

n=12 (100%)

Yes

8 (100%) 4 (100%) 12 (100%)

No

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

Total 8 (100%) 4 (100%) 12 (100%)

3.4 Identification of the RIPH and CI’s

Category

It took between 45 and 75 minutes for the experts to

analyse the 7 use cases and answer the ICTROUVE

evaluation questionnaire.

The experts’ first task was to recognise which

synopses corresponded to RIPH studies (falling under

the scope of the Jardè law) and which corresponded

to clinical investigations (falling under the scope of

the MDR). This task was to be carried out without the

help of ICTROUVE, leaving the experts to proceed

as usual. The 9 experts analysed 7 synopses each (63

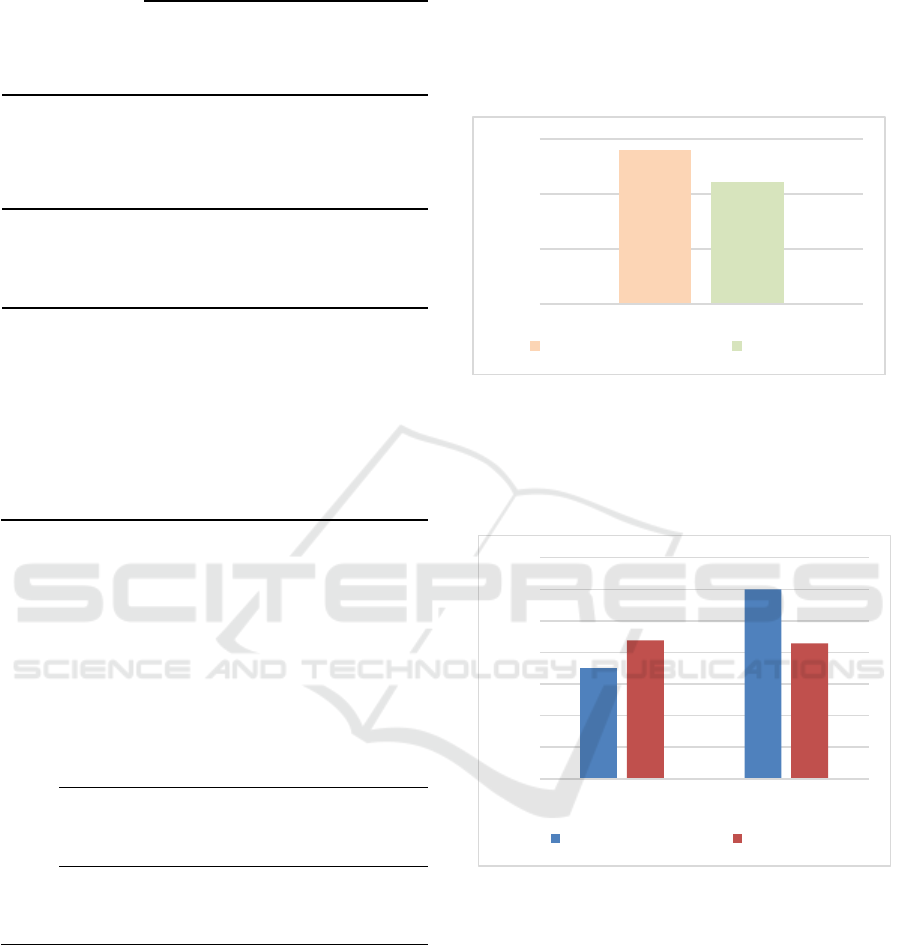

tests have been performed in total). Figure 1 presents

the number of synopses adequately recognised as

RIPH studies or clinical investigations by regulatory

managers and researchers.

Figure 1: Correct identification of clinical investigations.

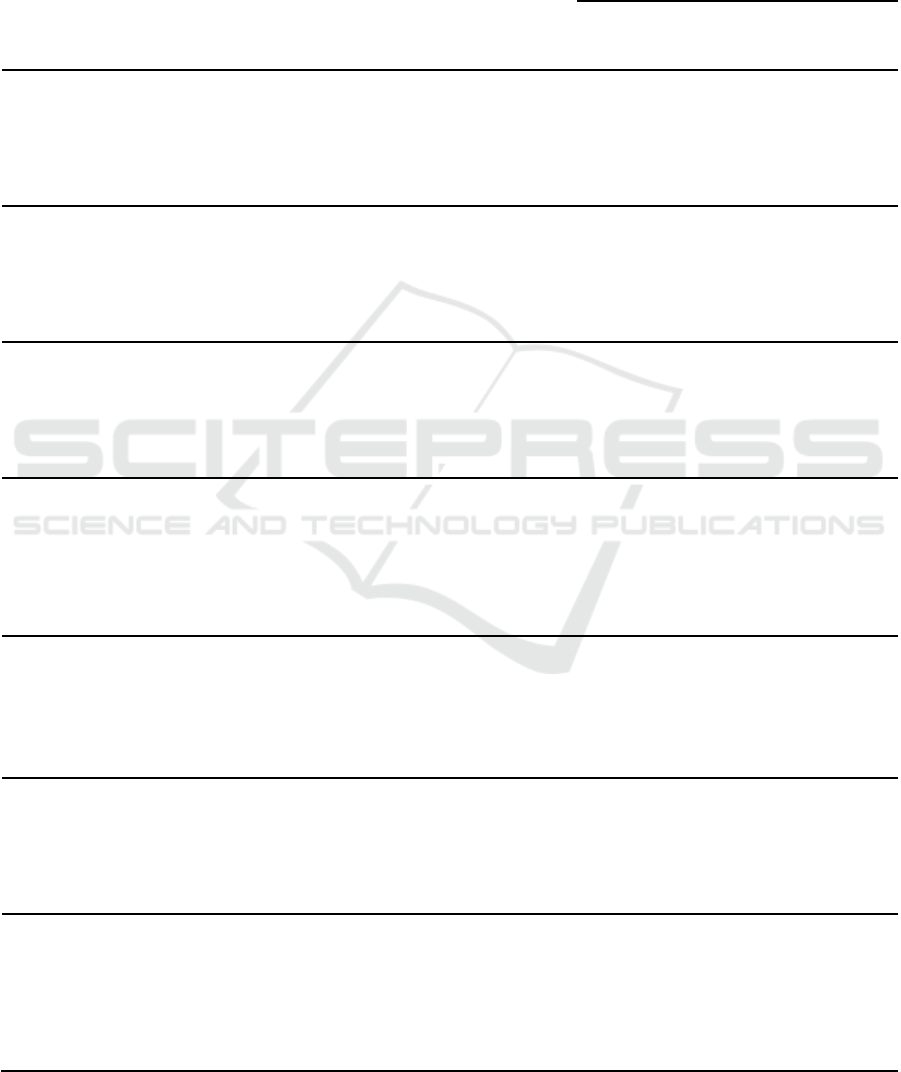

Regarding IC’s categories, the 9 experts analysed

4 synopses first without and then with the assistance

of ICTROUVE (36 tests have been performed in

total). Results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Correct identification of clinical investigations’

categories without and with ICTROUVE.

Without ICTROUVE, the correct overall response

rate averaged 39% (14 out of 36). For researchers, the

correct response rate was 43.8% (7/16). For

regulatory managers, it was 35% (7/20) (p=0.734).

With ICTROUVE, the correct overall response

rate averaged 42.8% (15/35). For researchers, the

correct response rate was 42.9% (6/14). For project

managers, the rate was 60% (9/15) (p=0.466).

Out of the 29 CI studies recognised as such by the

experts, the application of ICTROUVE yielded

divergent results compared to the method without

ICTROUVE in 7 (23%) cases. Of these 7 cases, the

n=24

(55,8%)

n=19

(44,2%)

0%

20%

40%

60%

Regulatory manager Researcher

35,0%

60,0%

43,8%

42,9%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Without ICTROUVE With ICTROUVE

Regulatory manager Researcher

Use of a Digital Positioning and Categorisation Aid for Clinical Investigations on Medical Devices: Questioning the Complexity of the Field

and Harmonizing Stakeholders’ Understanding

867

use of ICTROUVE resulted in the identification of

the correct CI category on 4 (57%) occasions.

3.5 Results of the ICTROUVE

Usability Survey

The results of the ICTROUVE usability survey are

presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Usability survey.

Regulatory

mana

g

ers

Researchers Total

n=4 (50%) n=4 (50%) n=8 (100%)

ICTROUVE is easy to use

totally agree 4 (80%) 2 (50%) 6 (67%)

agree 0 (0%) 1 (25%) 1 (11%)

neither agree nor disagree 1 (20%) 1 (25%) 2 (22%)

disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

ICTROUVE questions are clea

r

totally agree 1 (20%) 1 (25%) 2 (22%)

agree 3 (60%) 2 (50%) 5 (56%)

neither agree nor disagree 1 (20%) 1 (25%) 2 (22%)

disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

Compared with the standard method, ICTROUVE is more satisfactor

y

totally agree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

agree 3 (60%) 2 (50%) 5 (56%)

neither agree nor disagree 2 (40%) 2 (50%) 4 (44%)

disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

Compared with the standard method, ICTROUVE meant that I didn't forget any important criteria when identifying the

right CI category.

totally agree 3 (60%) 0 (0%) 3 (33%)

agree 1 (20%) 2 (50%) 3 (33%)

neither agree nor disagree 1 (20%) 1 (25%) 2 (22%)

disagree 0 (0%) 1 (25%) 1 (11%)

strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

Compared with the standard method, I'm more confident in my ability to identify the right CI category with ICTROUVE.

totally agree 1 (20%) 0 (0%) 1 (11%)

agree 1 (20%) 1 (25%) 2 (22%)

neither agree nor disagree 3 (60%) 3 (75%) 6 (67%)

disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

Additional information (definitions, etc.) should be added to facilitate completion.

totally agree 2 (40%) 1 (25%) 3 (34%)

agree 3 (60%) 1 (25%) 4 (44%)

neither agree nor disagree 0 (0%) 1 (25%) 1 (11%)

disagree 0 (0%) 1 (25%) 1 (11%)

strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

If ICTROUVE's ability to identify the category of a CI was equivalent to that of the usual method, I would prefer to use

ICTROUVE

totally agree 1 (20%) 3 (75%) 4 (44%)

agree 3 (60%) 0 (0%) 3 (33%)

neither agree nor disagree 0 (0%) 1 (25%) 1 (11%)

disagree 1 (20%) 0 (0%) 1 (11%)

strongly disagree 0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

ClinMed 2024 - Special Session on European Regulations for Medical Devices: What Are the Lessons Learned after 1 Year of

Implementation?

868

4 DISCUSSION

The European Medical Device Regulation adopted in

2017 strengthens the safety and performance

requirements imposed on medical devices (MD). This

reinforcement has an impact particularly on clinical

investigations (CI), which, in themselves, are already

time-consuming and costly.

Our survey suggests that the preparation of CI

application dossiers to the ANSM, the French

competent authority, is complex. We found little

agreement between the CI categories identified by the

experts and those finally assigned by ANSM.

Concordance was found in only 14 of the 36 cases

(39%), even if we could argue that knowledge of the

detailed projects could enhance this result.

ICTROUVE could serve as a facilitator for this

task. Although some modifications could be

considered, the usability survey showed that

ICTROUVE did indeed appear to be a good guide,

easy and quick to use according to the majority of the

participants. The concordance between the CI

categories identified with ICTROUVE and those

issued by the ANSM was 51.7%. However, its

performance needs to be validated by a larger-scale

study. This future confirmation will require the

participation of experts, such as researchers and

regulatory managers, in charge of preparing

submission dossiers to the ANSM, and in a sufficient

number. It will also require a large number of use

cases to be tested. The survey we conducted provided

information that could increase the feasibility of these

two key aspects of the next stages of this research.

During a webinar on the theme of clinical

investigations under Regulation 2017/745, the

ANSM presented the results of an analysis examining

the 284 CI authorisation applications submitted

between May 26, 2021, and February 28, 2022.

Within this pool of applications, 46 (16.2%) were in

the IC1 category, 47 (16.5%) in the IC2 category, 4

(1.4%) in the IC3 category, 113 (39.8%) in the IC4.1

category, 50 (17.6%) in the IC4.2 category, 11 (3.9%)

in the IC4.3 category and 13 (4.6%) in the IC4.4

category. It appeared that 216 (76%) applications

were validated, but only 30 (10.5%) in the first round.

The very low rate of acceptance in the first round

implies additional costs and delays for setting up the

CI, or even the abandonment of the project due to the

impossibility for manufacturers to respond to

ANSM's requests and complete their dossier (in 34

(12%) cases) (ANSM, 2022).

There are several potential reasons for ANSM's

refusal at this stage, such as an incomplete application

or a request that doesn't align with a CI but rather to

a RIPH study. It is important to identify the causes of

errors in order to propose appropriate solutions.

A first cause of error might stem from the

distinction between CI and RIPH. Indeed, it may be

difficult to know whether the research project

concerns a clinical investigation of a medical device.

In our tests, errors at this stage could concern up to

one third of the cases. An additional error could arise

from misidentifying the CI category. Participants in

our study reported a strong need for help on this

particular point. To the question, "Do you think a tool

to help identify the clinical investigation category of

a medical device would be useful to you?" the 12

experts questioned in phase 1 answered in the

affirmative. In addition, several participants

expressed a strong lack of confidence in their ability

to carry out the CI category identification exercise.

This lack of confidence seems to reflect a real

difficulty. Our results highlight a significant

discrepancy between the categories identified by the

experts, with or without the help of ICTROUVE, and

the categories validated by the ANSM. Without

ICTROUVE, the experts correctly identified the CI

category in 39% of cases. With ICTROUVE, this

success rate rose to 51.7%.

The number of decision nodes required to identify

the correct one is very large, and the definitions of CI

categories are very close to each other. In addition,

the definitions are difficult to interpret. For example,

the sponsor must assess whether the additional

procedures provided for in the clinical investigation

plan should be considered burdensome and/or

invasive. Burdensome additional procedures can

include a wide variety of different interventions,

including procedures that may cause pain,

discomfort, fear or potential risks or side effects,

disruption of life and personal activities, or other

unpleasant experiences. Burdensomeness is primarily

determined from the point of view of the person

bearing the burden. Invasive procedures include, but

are not limited to, penetration inside the body,

including through the mucous membranes of body

orifices, or penetration through a body orifice

(Medical Device Coordination Group, 2021).

Regarding the use of ICTROUVE, the feedback

from our 9 experts was positive, suggesting that it was

easily learned, user-friendly and that the questions

were clearly formulated. Finally, if ICTROUVE's

ability to identify the category of a CI was equivalent

to that of the standard method, 7 (77%) participants

said they would prefer to use ICTROUVE rather than

the standard method.

However, several improvements could be

envisaged. After ICTROUVE has been used, a button

Use of a Digital Positioning and Categorisation Aid for Clinical Investigations on Medical Devices: Questioning the Complexity of the Field

and Harmonizing Stakeholders’ Understanding

869

to submit a new application would be useful. A

majority of participants indicated a need for additional

information to facilitate filling in ICTROUVE. The

most frequently requested information concerned

definitions of MD characteristics (implantable, etc.).

One expert would have liked concrete examples to

illustrate the questions. Finally, ICTROUVE failed on

one occasion in which it proposed no new questions

and no results.

The use cases we provided to participants did not

mention the class of the MD. This information is

essential for identifying the CI category and is

complex to determine. This adds a further source of

error that can reduce performance with and without

ICTROUVE. Participants reported not having to

identify the class of the MD in their real working

lives. Furthermore, if the purpose of the study was

mentioned in the use cases, most participants would

have preferred it to be presented unambiguously. In

real life, these ambiguities are typically resolved

through direct communication with the manufacturer

or principal investigator.

This may explain why ICTROUVE, while not

judged less satisfactory than the standard method,

was not judged more satisfactory either, with 5 (56%)

experts "agreeing" and 4 (44%) "neither agreeing nor

disagreeing". Similarly, only 3 (33%) participants

answered "strongly agree" or "agree" to the question

"Compared to the standard method, I'm more

confident in my ability to identify the right CI

category with ICTROUVE". The remaining 6 (67%)

answered "neither agree nor disagree".

There are a number of limitations to this survey.

The first relates to the questionnaire used to collect

part of the results (Stratton, 2012, 2015). The

response rate remains unknown, and the potential for

significant differences between respondents and non-

respondents has yet to be established. Respondents

may not be representative, as a voluntary effect is

always possible. It is also possible that the people

who responded are precisely those individuals who

strongly felt the most important need for assistance in

identifying the CIs categories. However, even if, in

the worst-case scenario, the study population were

not representative of the target population, and even

if only some of the experts were to declare a need for

help, ICTROUVE's existence would still be justified,

provided that this number of people was sufficiently

large. The unanimous expression of the need for

assistance from all participating experts indicates that

such a necessity is widespread.

An additional constraint that could impact the

representativeness of the study population is the fact

that all the experts belonged to public institutions. The

experts involved (in industry, in contract research

organisations) may have specific functions and

encounter specific difficulties which would be

interesting to study. Nevertheless, even if ICTROUVE

were to be evaluated and judged as performing well

only in the academic arena, this would be sufficient

justification for having developed and disseminated it.

It is also possible that the questions were worded

in such a way that the opinions and prejudices of the

researchers influenced the people who responded to

the survey. The questions to be asked in the next steps

of our work will have to be carefully worked out and

tested to prevent such bias.

Our questionnaire offered the opportunity to

participate voluntarily and without obligation but did

not give the option of remaining anonymous. These

choices may explain the low number of responses

obtained, a number which confers reduced statistical

power to our study. However, the purpose of this

survey was to determine the feasibility of a larger

survey, and it therefore did not require significant

statistical power (Brooks & Stratford, 2009). This

larger study will enable the hypotheses formulated to

be tested more rigorously.

In light of the small number of experts recruited

for phase 2, we chose to ask them all to identify the

CI categories with and without ICTROUVE. It cannot

be ruled out that the identification without

ICTROUVE had an influence on the identification

with ICTROUVE. However, all the experts worked in

the same order, first without and then with

ICTROUVE, which appeared to us to be the least

biased. The use of ICTROUVE is highly

standardised, leaving little room for interpretation.

Within the framework of the larger study to be

conducted, a way to eliminate this bias could be found

in the randomisation of experts into "STANDARD

method" versus "ICTROUVE method" clusters.

Another limitation is that we were unable to carry

out the study under real-life conditions. One of the

aims of the survey was to gain a better understanding

of how the experts responsible for identifying CI

categories work. The information obtained in our

survey suggests that, while the identification of CI

categories is initially carried out individually, it is

often followed by collegial work, which we did not

replicate. The next steps will need to consider the

possibility of allowing experts to work in groups.

Some of the experts' comments also indicated that

they often turn to the manufacturers or principal

investigators for further clarification. This mainly

concerns technical information on the MD, and

information on the purpose and methodology of the

study. In the context of the next steps we intend to

ClinMed 2024 - Special Session on European Regulations for Medical Devices: What Are the Lessons Learned after 1 Year of

Implementation?

870

follow in our study, this information will have to be

taken into account and a solution found to make it

available to the experts.

Our search for use cases indicates that they are not

yet widely available and are very difficult to collect.

As the EUDAMED database is not yet operational on

all aspects, synopses have been obtained via

university hospitals directly. This data collection

method frequently necessitates acquiring

authorisation from the principal investigator to utilise

information pertaining to their studies. Furthermore,

the individuals interviewed during phase 1 indicated

a scarcity of use cases available for sharing. An

approach involving the ANSM directly would make

it possible to obtain a larger number of cases through

a single contact, as well as involving the authority for

its opinion and input on the ICTROUVE solution.

Collecting a sufficient number of use cases is an

essential point. An insufficient number would reduce

statistical power, limit the choice of the most

appropriate methodology, and make it impossible to

work on all existing CI categories. According to

ANSM, certain categories are poorly represented (e.g.

IC3 and IC4.3). However, it is possible that some CI

categories are more difficult to identify.

Finally, we considered that the CI categories

identified by ANSM were correct. It is indeed

important that ICTROUVE arrives at the same CI

categories as the ANSM, since it is the latter that does

or does not authorise CIs. However, there could be

discrepancies between the ANSM and the new MD

regulations. Verifying this hypothesis could be one of

the objectives of the next steps.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Our work identified a real difficulty for experts and

researchers to identify the CI category in France.

Inherent difficulties arising from the text issued from

the ANSM could constitute an explanation. Another

one is that the task is highly complex and requires a

great deal of interpretation. It is not unlikely that such

a subjective process will be observed in any EU

country. A validated computer aid like ICTROUVE

could remove the need for interpretation and improve

the concordance between competent authorities,

researchers and regulatory managers.

Our study points out that a larger-scale study

would be useful and feasible. ICTROUVE appears to

be well designed, and the few suggestions for

improvement put forward by expert users seem

straightforward to implement. Finally, the survey

gathered information that could prove relevant to the

prospective implementation of a larger-scale study,

particularly with regard to the process of collecting

use cases and finding experts.

It might be worth extending this work to the

European level in order to identify possible needs for

assistance and to develop a continental tool that

would not only simplify national research but also

facilitate and harmonise international research.

REFERENCES

Académie nationale de médecine. (2022). Un risque réel de

pénurie de dispositifs médicaux. Bulletin de l’Académie

Nationale de Médecine, 206(8), 921‑922.

ANSM. (2022). Les investigations cliniques DM selon le

règlement 2017/745—Webinaire #5 (accessed 12.28.23).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wOEsXkeJDPY

Brooks, D., & Stratford, P. (2009). Les études pilotes :

Déterminer si elles peuvent être publiées dans

Physiotherapy Canada. Physiother Can, 61(2), 67.

Chevallier, T., Bastide, L., & Potier, H. ICTROUVE.

(accessed 12.28.23). https://rc.chu-nimes.fr/surveys/?s=J

E39NHHC9L7WY8KW .

HAS. (2017). Parcours du dispositif médical en France.

(accessed 12.28.23). https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/

docs/application/pdf/2009-12/guide_pratique_dm.pdf

Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG). (2021).

Regulation (EU) 2017/745 – Questions & Answers

regarding clinical investigation. (accessed 12.28.23).

https://health.ec.europa.eu/medical-devices-sector/new-

regulations/guidance-mdcg-endorsed-documents-and-

other-guidance_en

Medical devices must be carefully validated. (2018). Nature

Biomedical Engineering, 2(9), 625‑626.

Regulation UE 2017/745. (2017). Règlement 2017/ 745 du

parlement européen et du conseil relatif aux dispositifs

médicaux. (p. 175).

Sayin, H., Gaillard, C., Henry, A., Cabelguenne, D., &

Armoiry, X. (2022). Impact du nouveau règlement

européen 2017/745 relatif aux dispositifs médicaux sur

l’activité des pharmacies hospitalières : Exemple de la

fonction d’approvisionnement pharmaceutique au sein

d’un centre hospitalo-universitaire français. Annales

Pharmaceutiques Françaises, 80(5), 730‑737.

SNITEM. (2022). Panorama 2021 et analyse qualitative de

la filière industrielle des dispositifs médicaux en France.

(accessed 12.28.23). https://www.snitem.fr/wp-content/

uploads/2022/02/Snitem-Panorama-DM-2022.pdf

SNITEM. (2020). Nouveau panorama de la filière

industrielle des dispositifs médicaux en France.

(accessed 12.28.23) https://www.snitem.fr/presse/nouve

au-panorama-de-la-filiere-industrielle-des-dispositifs-

medicaux-en-france/.

Stratton, S. J. (2012). Publishing Survey Research. Prehosp

Disaster Med, 27(4), 305‑305.

Stratton, S. J. (2015). Assessing the Accuracy of Survey

Research. Prehosp Disaster Med, 30(3), 225‑226.

Use of a Digital Positioning and Categorisation Aid for Clinical Investigations on Medical Devices: Questioning the Complexity of the Field

and Harmonizing Stakeholders’ Understanding

871