Cybersecurity Incident Response Readiness in Organisations

Aseel Aldabjan

1,2

, Steven Furnell

1

, Xavier Carpent

1

and Maria Papadaki

3

1

School of Computer Science, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, U.K.

2

College of Computer and Information Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, K.S.A.

3

School of Computing and Engineering, University of Derby, Derby, U.K.

Keywords: Cybersecurity Readiness, Organisational Readiness, Cybersecurity Preparedness, Cybersecurity Maturity,

Security Incident Readiness.

Abstract: The number and nature of cyber-attacks is continuously evolving, disrupting the productivity and operations

of organisations worldwide. Timely and effective detection and response to incidents are important, as they

could limit the spread of threats and restrict the risks from compromises. Studies have revealed the level of

preparedness to respond for many organisations is low and varies across different industry sectors. At the

same time, cybersecurity researchers have identified a substantial gap in implementing readiness assessment

frameworks as they are dependent on the type, context and specific requirement of the respective industries.

Moreover, organisations have a gap between their practices and the establishment of the measures. This

highlights the need for a more comprehensive and holistic framework to address this issue. This paper aims

to determine the current state of incident response practices across organisations of different sizes and

capabilities. It further seeks to identify the factors that influence them to reach the desired level of cyber

security readiness.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cyber security readiness is an organisation’s ability

to respond to incidents in terms of its capabilities,

resources and infrastructure (Cisco, 2023). This

involves having critical policies, procedures and

trained personnel in place to respond to security

incidents. Therefore, cyber security readiness refers

to the degree to which an organisation is aware of,

prepared for and committed to preventing and

responding to all aspects of an incident (Deloitte,

2016). The lack of cyber security readiness can pose

significant challenges for organisations in acquiring

the necessary resources to establish a sufficient level

of cyber security and safeguard their digital assets.

Being prepared to respond to security incidents is

crucial for minimising impacts and restoring

operations. Yet, the readiness and capability to

respond to incidents vary considerably among

organisations. Therefore, this study aims to explore

the existing practice gap in IR readiness across

organisations of different sizes and capability and to

identify the factors that impede their preparedness to

respond to such incidents.

The next section provides insights into the

organisation's security readiness in practice. This is

followed by an overview of influential factors of

cyber security preparedness. Subsequently, the

correlations among these factors are outlined. Finally,

the conclusion and future work are presented.

2 ORGANISATION’S SECURITY

READINESS IN PRACTICE

IR readiness has a wide scope and the related

practices may vary based on the organisation’s size

and its industry. This section examines evidence from

various sources that determine the readiness and

preparedness challenges of organisations.

A survey by IBM (2022) including 17 industries

across 17 countries highlighted that organisations

with dedicated IR teams and proper IR plans saved an

average of $2.66 million compared to those without

these practices. Similarly, Deloitte (2023) conducted

a survey of over 1000 cyber decision-makers across

20 countries, revealing that only 21% reached a high

cyber maturity level, where they meet the leading

practices requirement that ensures IR readiness.

262

Aldabjan, A., Furnell, S., Carpent, X. and Papadaki, M.

Cybersecurity Incident Response Readiness in Organisations.

DOI: 10.5220/0012487600003648

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2024), pages 262-269

ISBN: 978-989-758-683-5; ISSN: 2184-4356

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

BakerHostetler (2023) highlighted that the

average response time of an incident from the time of

occurrence to detection is 3 days, followed by 24 days

for forensic investigation, and a further 67 days to

inform the stakeholders. The average time for

recovery is increased for all industries, which may be

attributed to various factors including delays in

detection and responding and inadequate preparation

and planning for business continuity. This data

reveals a frequent occurrence of delays. This means

that it is necessary for organisations to effectively

respond to an incident on time and that any response

delays can potentially lead to higher losses and costs.

The UK Cyber Security Breaches Survey (2023)

includes focus on the consequences of incidents and

breaches, and demonstrates organisations’ current

preparedness in addressing cyber attacks. One of the

concerning findings was that despite the increasing

prevalence of cyber attacks, small organisations tend

to have less priority over preparation to respond to an

incident and allocate less resources to deal with cyber

attacks. This may have a considerable impact on their

overall preparation, capability and readiness to

respond to incidents. Furthermore, organisations that

adopt proper IR plans to address cyber incidents

remain a minority. Larger organisations have a higher

probability of establishing such plans with 64% of

them have established formal IR plans. Furthermore,

the report noted a disconnect in communication

regarding IR between security specialists or IT teams

and other staff, including management boards.

Therefore, the report recommended filling the

existing gap pertaining to establishing constant and

streamlined communication between IT team and

other members of staff.

The Cisco Cybersecurity Readiness Index (2023)

revealed that only 15% of organisations worldwide

have a sufficient level of maturity to prepare against

the actual threat level they encounter. However, the

report also stated that readiness is dependent on the

industry sector. Industries that are more prone to

vulnerability and have a higher potential to suffer

losses tend to have a higher matured level of

readiness, such as the healthcare (18%) and financial

(19%) sectors. It is worth noting that organisations in

the retail sector have the highest percentage of

maturity at 21%. This may be because this industry

has been exposed to a higher number of cyber attacks

over the past years

This review suggests that a significant number of

organisations encounter challenges in filling the

critical gaps in security preparation. These gaps, such

as the lack of planning in responding to potential

incidents, impede rapid detection, effective

mitigation and efficiency in security incident

recovery. Organisations with a lack of proper and

tested plans in place can potentially face higher

significant losses and damages in comparison to those

with established security protocols. In addition, there

is an evident gap between small and large

organisations. The study suggests that bigger

organisations tend to be more prepared than smaller

organisations, leading to the latter experiencing

higher damages when such incidents occur. Overall,

organisations should improve their readiness to

combat such incidents. Therefore, understanding the

factors that impact preparedness in organisations is

crucial, which will be discussed in detail in the next

section.

3 FACTORS IMPACTING

CYBERSECURITY READINESS

An organisation's readiness to respond to incidents

can be significantly affected by several factors. Each

of these factors can have substantial impacts on the

organisation's readiness. Therefore, it is essential that

organisations take into consideration all these factors

when evaluating and preparing for a potential

incident. Despite the significance of cybersecurity

readiness, a literature review indicates a lack of

comprehensive examinations of the diverse factors

that can contribute to cybersecurity preparedness, and

their cumulative impact. Furthermore, there is a

shortage of effective methods for evaluating

preparedness. Hence, there is a need for research to

comprehensively identify these factors and examine

their overall contribution within a more holistic

framework. In this research, the identification of

relevant factors was approached through an extensive

review of related literature to establish the situation

from both academic and practitioner perspectives. For

the academic aspect, a comprehensive search was

conducted across scholarly databases (e.g. IEEE

Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and Science Direct)

targeting articles from 2013-2023. An accompanying

search of industry, government and professional

sources was also conducted for the same period.

The search terms that were adopted include

‘cybersecurity factors’, ‘cybersecurity readiness’,

‘organisational readiness’, ‘cybersecurity resilience’,

‘cybersecurity preparedness’, ‘cybersecurity

maturity’, ‘cybersecurity compliance’, and ‘security

incident readiness’. The articles found were

shortlisted and reviewed to determine their suitability

and relevance. The resulting factors identified

Cybersecurity Incident Response Readiness in Organisations

263

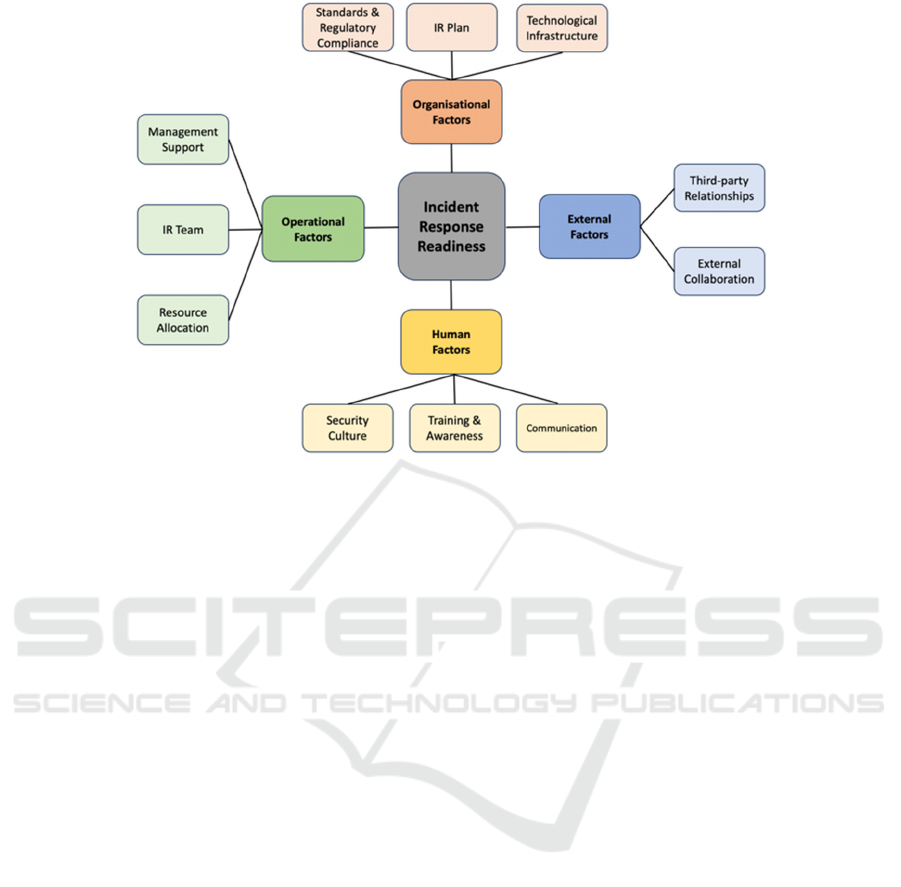

through the review were classified into four

categories (human, organisational, operational, and

external), as depicted in Figure 1. While the factors

themselves are already recognised in the literature,

the framework provides a new basis for

understanding them and their collective influence.

3.1 Human Factors

Several human factors can play a role in an

organisation's readiness. These include security

culture, training and awareness, and communication.

3.1.1 Security Culture

Security culture has a significant impact on readiness.

In several studies, organisational security culture has

been identified as one of the major factors influencing

incident readiness(Berlilana et al. 2021; Hasan et al.

2021) . A lack of security culture can undermine even

the strongest technical measures. Moreover, Frenken

(2020) indicates that cybersecurity culture aims to

protect all organisational assets by developing a risk-

aware mindset throughout organisations. This allows

for improved compliance with regulatory

requirements, as well as improved response times to

cybersecurity threats. When people feel a sense of

responsibility and ownership over the security of an

organisation, they are more likely to take proactive

measures to prevent incidents from occurring and to

response quickly in the event of an incident.

3.1.2 Training and Awareness

Employee training and awareness can significantly

impact an organisation's readiness for cybersecurity

incidents. For instance, studies have demonstrated

that training employees in order to enhance their

response abilities and asset protection capabilities is

important (Hasan et al. 2021). Developing these skills

can help employees to better anticipate potential risks

and respond quickly and effectively when they arise.

Other studies have shown that security awareness is

also an important factor of readiness. Therefore,

ongoing employee training and awareness are likely

to play a significant role, given that hackers regularly

adopt new attack methods (Aldawood and Skinner,

2019a). Furthermore, it has been emphasised that it is

essential for HR departments to include training as a

central part of employee onboarding in order to

ensure a sufficient level of employee proficiency in

dealing with threats and incidents (Aldawood and

Skinner, 2019b). Therefore, providing employees

with the skills and awareness with which to recognise

security risks will improve IR capabilities.

3.1.3 Communication

One fundamental component of an organisational IR

is effective communication. It involves internal

communication with top management, staff,

members of the IR team, and other stakeholders, as

well as external contacts such as clients and suppliers.

Effective communication is paramount to enable

coordinated and swift response actions during and

after crises. An organisation must define roles and

responsibilities and establish information-sharing

protocols and clear communication channels to

implement an effective communication strategy

(Manley and McIntire, 2020). The NIST

Cybersecurity (NIST, 2023) framework highlights

communication as a key component of best practices

for IR, and its recommendations stress the need for

organisations to have comprehensive strategies that

outline how internal and external information will be

shared during incidents. It highlights the significance

of well- structured and proactive communication to

better manage cyber-related incidents.

3.2 Organisational Factors

To ensure that an organisation is ready to respond,

several factors must be taken into consideration

within the organisational context. These factors

include technological infrastructure, IR plan and IR

standards and regulatory compliance.

3.2.1 Technological Infrastructure

Technological infrastructure is a major factor that

affects readiness (Hasan et al. 2021). Researchers

have found that organisations with technological

infrastructure development will be better prepared to

deal with incidents (Berlilana et al. 2021). This entails

having the latest technology, including devices,

programmes, and other elements, along with

knowledge of how to use and maintain it. Therefore,

an up-to-date technological infrastructure is an

essential factor in incident preparedness.

In addition, industry surveys have revealed that

outdated technology poses a significant risk that can

impede a proper IR. For example, Verizon’s DBIR

report (2022) indicated that outdated technology and

applications are the most common incident vectors

that negatively impact the response capability of

organisations. Furthermore, the report noted that

more than half of all system intrusion incidents were

caused by vulnerabilities in partner technology.

Therefore, organisations must not only ensure that

their infrastructure is updated, but also that their

partners and vendors adhere to best practices.

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

264

Figure 1: Cybersecurity readiness factors.

3.2.2 Incident Response Plan

The effectiveness of an organisation’s capacity and

readiness to respond to cyber incidents crucially

depends on its IR plan, which refers to a structured

and documented approach outlining the clear steps,

procedures, and actions that an enterprise should

undertake when it detects a security incident. It is a

vital roadmap for identifying, responding to, and

minimising cyber incidents (Cynet, 2019). Constantly

updating the IR plan and complementing it with

simulated incidents and tabletop exercises ensures the

company’s readiness to tackle cyber incidents (Jalali

et al. 2019). Another study underlined the necessity

of well-documented and regulated tested IR plans,

emphasising the need for organisations to develop an

IR plan and ascertain its ongoing relevance by

regularly updating and testing it (Wertheim, 2019).

Therefore, organisations must develop robust plans

that align with best practices and are required to make

organisations ready to respond.

3.2.3 Regulatory and Standards Compliance

An organisation’s ability to address cybersecurity

risks can be significantly enhanced through

compliance with standards and laws. According to

Berlilana (2021), adhering to industry standards and

government regulations can bolster the ability of an

organisation to tackle cyber-attacks. In this context,

compliance refers to organisations adhering to

specifications, guidelines, regulations, and laws

relevant to their operations and procedures. Industry

standards can improve readiness across a sector.

Several researchers have cited the fact that

organisations that follow industrial standards, such as

the NIST and information security governance

frameworks, are more likely to respond effectively to

cybersecurity incidents (Georgiadou et al. 2022).

3.3 Operational Factors

Various factors affect cybersecurity readiness from

the operational perspective, namely management

support, resource allocation, and a dedicated IR team.

3.3.1 Management Support

Another important factor that influences

cybersecurity readiness lies in leaders’ attitudes and

support (Hasan et al. 2021). Several studies have

demonstrated that leadership is a critical component

of IR readiness and that lack of leadership can reduce

the quality of response (Benz & Chatterjee, 2020).

Similarly, Bahuguna et al. (2019) found that lack of

senior leadership support is one of the challenges

faced by entities in enhancing their cybersecurity

preparedness. Cisco’s Readiness Index (2023) states

that it is the responsibility of business leaders to

develop baseline IR standards across major security

pillars to enhance their organisations’ resilience.

Moreover, researchers have found that organisations

are more vulnerable to the negative impacts of

cybersecurity incidents when leaders are unprepared

Cybersecurity Incident Response Readiness in Organisations

265

or overconfident. For example, recent studies in the

healthcare industry have found that infrequent

interactions between organisational leaders and chief

information security officers (CISOs) and a lower

resource commitment to IR reduce the level of

preparedness in organisations (Abraham et al. 2019).

Therefore, effective leadership is essential for

ensuring cybersecurity preparedness and resilience.

3.3.2 Resource Allocation

Another crucial factor to take into account is the

availability of adequate resources such as budgets and

personnel, and how they are allocated. Organisations

with inadequate budgets for IR are at high risk, and at

present, nearly 56% of organisations must allocate

more funds to ensure cybersecurity (Cisco, 2023). In

addition to funding, the allocation of resources also

includes the allocation of manpower and personnel

within an organisation. An organisation’s ability to

respond to an incident is greatly influenced by the

availability of sufficient personnel resources (Hasan

et al. 2021). Moreover, Quader and Janeja (2021)

found that lack of investment in the workforce and IT

infrastructure are key impediments to a secure cyber

environment. These resources enable organisations to

detect, investigate, and mitigate incidents more

effectively, enabling quicker and more efficient

response to incidents, and ultimately reducing the

damage caused.

3.3.3 Dedicated Incident Response Team

Another crucial element that significantly impacts an

organisation’s readiness to mitigate or reduce

cybersecurity threats is the presence of a dedicated

cybersecurity IR team. NIST (2011) define the

Computer Incident Response Team as a group of

skilled staff structured to formulate, recommend, and

orchestrate prompt measures for containing,

eliminating, and recovering from cybersecurity

incidents. Rahman and Chao (2015) recognised the

composition of a IR team as a critical component in

the preparation stage. The responsibilities of this team

encompass incident assessment, developing and

implementing response strategies, creating situational

awareness, and incident triage (Ruefle et al. 2014).

Moreover, Ahmad et al. (2020) highlighted the

importance of IR team at the strategic level, which

covers the tools and strategies for securing the digital

assets of an organisation. Through effective policies,

the IR team can enable an organisation to regulate the

use of computing infrastructure, identify and mitigate

risks, and offer training programmes to ensure high

levels of employee awareness.

3.4 External Factors

The final outside an organisation can have a

significant impact on its cybersecurity preparedness.

3.4.1 Vendor / Third-Party Relationship

A vendor/third-party relationship is an essential

factor that impacts an organisation’s capability and

preparedness to respond to cyber incidents.

Organisations should assess and maintain the security

of external entities that interact with their IT

infrastructure. External entities can include service

providers, suppliers, and other third-party providers.

Research has indicated that vendors / third parties

play a pivotal role in an organisation’s cybersecurity

strategy, as they are often involved in or responsible

for many incidents (Keskin et al. 2021). Therefore,

organisations should comprehensively assess their

external partners to ensure that they meet certain

predefined security protocols and standards to

establish high levels of confidence and trust.

Ultimately, this can reduce the risk of a security

breach. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (NIST,

2023) underscores the significance of suppliers and

other external stakeholders as critical components of

IR. It provides best practices and guidelines to help

organisations incorporate vendor risk management

into their cybersecurity approaches and strategies. By

implementing NIST's guidelines, enterprises can lay

a strong foundation for responding to cyber threats

and enhancing their overall preparedness.

3.4.2 Collaboration with External Entities

External collaboration is another crucial element for

enhancing an organisation's preparedness and ability

to address cyber threats (Berlilana et al. 2021). Rajan

et al. (2021) highlight that collaboration with external

entities is one of the best approaches to identifying

cyber vulnerabilities and protecting information. The

authors argued that companies collaborating closely

with external parties can exchange accurate

information, providing larger systems with better

security than traditional, isolated security measures.

Numerous studies have empirically evaluated the

benefits of collaboration with competitors concluded

that organisations can more effectively identify and

mitigate cyber threats when their rivals constantly

update them of emerging attacks (Hasan et al. 2021).

However, this willingness to collaborate can be

attributed to the intense competition and lack of trust

that exists between organisations and the recognition

of information as a critical element in this

competition (Kertysova et al. 2018). In such cases,

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

266

organisations often hesitate to share information with

their competitors, allowing attackers to target similar

organisations. Therefore, sharing knowledge has the

potential to significantly reduce threats.

4 INTERRELATIONS AND

INFLUENCE OF THE FACTORS

Having identified the factors, it is also relevant to

recognise the potential for interrelationships between

them, and their varying levels of influence in different

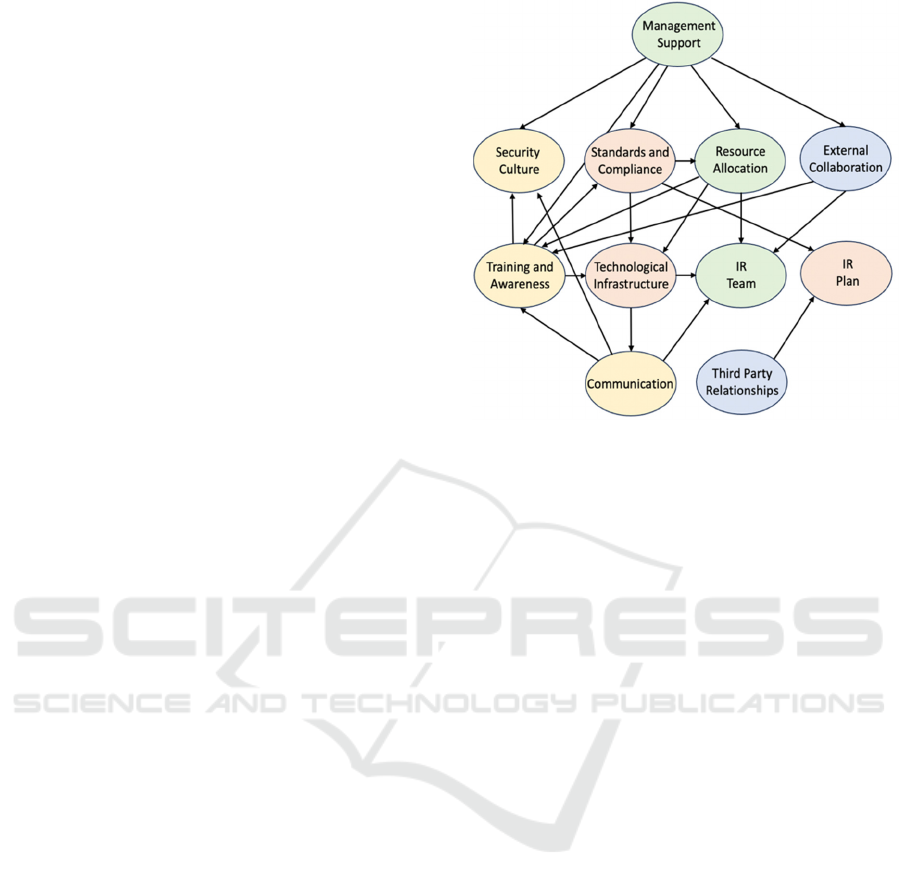

contexts. Addressing the first of these points, Figure

2 offers an initial attempt to identify key

interrelationships, based upon their representation in

the literature (note that the diagram maintains the

colour-coding from Figure 1, clearly highlighting

relations between factors across different groups).

While space precludes a full discussion of the Figure,

the following paragraphs present some illustrative

discussion of the relationships being depicted.

From this initial assessment, management support

serves as a foundational element influencing most

readiness parameters. For instance, it plays a crucial

role in establishing an organisation-wide security

culture (Huang & Pearlson, 2019; Safitra et al., 2023).

Informed senior executives have a direct influence on

raising awareness and training programs (Yusif &

Hafeez-Baig, 2021). A dedicated management team

ensures proper resource allocation for cybersecurity

initiatives (Daud et al., 2018), preventing ineffective

allocation and enhancing cybersecurity readiness. In

addition, management support is vital for ensuring

standards and regulations compliance, leading to

effective policies and standards implementation

(Berlilana et al., 2021). It is also often essential for

establishing strategic collaborations and alliances

with other organisations, enhancing security

capabilities through information sharing and resource

exchange (Rajan et al., 2021). In essence, the support

of management impacts nearly every facet of

preparedness, improving overall readiness for

cybersecurity incidents. Furthermore, there are

interconnected relationships among other readiness

factors; for instance, technological infrastructure is

both influences and influenced by various other

elements. For example, utilizing cutting-edge

technical systems, such as real-time decision-support

systems, enhances the operational performance of IR

teams by relieving them from manual tasks. This

allows them to focus on addressing critical issues and

potential threats, improving overall efficiency and

effectiveness (Naseer et al., 2021). Research has

Figure 2: Interrelations Among Readiness Factors.

shown that security incidents are often exploited by

attackers due to a lack of communication (Knight &

Nurse, 2020). Therefore, an effective cybersecurity

infrastructure can enable an organisation to establish

an effective corporate communication platform

(Serrano et al., 2023). This ensures organisations

strengthen their communication and incident

response capabilities. On the other hand, the

technological infrastructure is shaped by various

readiness factors. The compliance and adoption of

incident response frameworks such as ISO, NIST, and

others allow the establishment of efficient and robust

cybersecurity infrastructures (Shinde & Kulkarni,

2021). In addition, having adequate resources is

critical in developing and maintaining technological

infrastructures for maintaining and managing

cybersecurity (Berlilana et al., 2021). It is noteworthy

that bringing the security technological infrastructure

up to standard is unlikely to benefit an organisation if

those who work on these systems are neglected.

Enhancing employees' capabilities and skills through

training and awareness is crucial for the proper use of

new systems (Akter et al., 2022).

The interrelations illustrate that preparing for

cybersecurity incidents is not an isolated task, and

requires a suitable blend of multiple factors.

Organisations must understand the interconnections

of these factors to build a robust defence against cyber

threats, ensuring their sustainability and protecting

their stakeholders. We intend to further investigate

the real-world recognition of the factors and their

relative influence, in the next phase of the work, by

means of a survey amongst organisations in practice.

This will target security professionals and IT experts

Cybersecurity Incident Response Readiness in Organisations

267

across organisations of diverse sizes and industries,

and will consider the extent to which organisations

recognise incident response as an issue, as well as

how the feel in terms of readiness to handle it. The

categories of readiness factor will then be explored in

order to investigate the extent to which each is found

to be a relevant issue in practice. This will assist in

further determining potential interrelationships, as

well as providing at least an initial baseline view of

the relative influence of individual factors (or factor

categories).

5 CONCLUSIONS

The intricacies of organisational preparedness for

cybersecurity incidents are multifaceted, involving a

range of critical factors, including security culture,

training and awareness, communication, management

support, resource allocation, a dedicated IR team,

external collaboration, vendor/third-party relation-

ships, technological infrastructure, regulatory and

standards compliance, and the IR plan. The gap in

organisational readiness highlights the opportunity

for a tool that would assist in evaluating their

response readiness, and support them in taking related

actions to improve their posture, bridging the evident

practice gap and enhancing overall cyber security

readiness.

REFERENCES

Ab Rahman, N.H., & Choo, K.-K.R. (2015). A survey of

information security incident handling in the cloud.

Computers & Security, 49, 45-69.

Abraham, C., Chatterjee, D., & Sims, R.R. (2019).

Muddling through cybersecurity: Insights from the US

healthcare industry. Business Horizons, 62(4), 539-548.

Ahmad, A., Desouza, K.C., Maynard, S.B., Naseer, H., &

Baskerville, R.L. (2020). How integration of cyber

security management and incident response enables

organizational learning. Journal of the Association for

Information Science and Technology, 71(8), 939-953.

Akter, S., Uddin, M.R., Sajib, S., Lee, W.J.T., Michael, K.,

& Hossain, M.A. (2022). Reconceptualizing

cybersecurity awareness capability in the data-driven

digital economy. Annals of Operations Research.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04844-8

Aldawood, H., & Skinner, G. (2019a). Challenges of

implementing training and awareness programs

targeting cyber security social engineering. 2019

cybersecurity and cyberforensics conference (ccc),

Aldawood, H., & Skinner, G. (2019b). Reviewing Cyber

Security Social Engineering Training and Awareness

Programs-Pitfalls and Ongoing Issues. Future Internet,

11(3).

Bahuguna, A., Bisht, R.K., & Pande, J. (2019). Assessing

cybersecurity maturity of organizations: An empirical

investigation in the Indian context. Information

Security Journal: A Global Perspective, 28(6), 164-

177.

BakerHostetler. (2023). 2023 Data Security Incident

Response Report,. bakerlaw.com. https://www.baker

law.com/webfiles/2023%20DSIR%20Report.pdf

Benz, M., & Chatterjee, D. (2020). Calculated risk? A

cybersecurity evaluation tool for SMEs. Business

Horizons, 63(4), 531-540.

Berlilana, Noparumpa, T., Ruangkanjanases, A., Hariguna,

T., & Sarmini. (2021). Organization Benefit as an

Outcome of Organizational Security Adoption: The

Role of Cyber Security Readiness and Technology

Readiness. Sustainability, 13(24).

Cisco. (2023). Cybersecurity Readiness Index Resilience in

a Hybrid World. Cisco. https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/

m/en_us/products/security/cybersecurity-reports/cyber

security-readiness-index/2023/cybersecurity-readiness

-index-report.pdf

Cynet. (2019). NIST Incident Response Plan: Building your

IR process. Cynet. https://www.cynet.com/incident-

response/nist-incident-response/

Daud, M., Rasiah, R., George, M., Asirvatham, D., &

Thangiah, G. (2018). Bridging the Gap between

Organisational Practices and Cyber Security

Compliance: Can Cooperation romote Compliance in

Organisations? International Journal of Business and

Society, 19(1), 161-180.

Deloitte. (2023). 2023 Global Future of Cyber Survey,

.

https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/services/risk-

advisory/content/future-of-cyber.html

Deloitte. (2016). Readiness, response, and recovery: Cyber

crisis management. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/

dam/Deloitte/ch/Documents/audit/ch-en-cyber-crisis-

management.pdf.

Frenken, P. (2020). Why Build a Cybersecurity Culture?,.

ISACA. 22 October 2020. https://www.isaca.org/

resources/news-and-trends/isaca-now-blog/2020/why-

build-a-cybersecurity-culture

Georgiadou, A., Mouzakitis, S., Bounas, K., & Askounis,

D. (2022). A cyber-security culture framework for

assessing organization readiness. Journal of Computer

Information Systems, 62(3), 452-462.

Hasan, S., Ali, M., Kurnia, S., & Thurasamy, R. (2021).

Evaluating the cyber security readiness of organizations

and its influence on performance. Journal of

Information Security and Applications, 58, 102726.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2020.102726

Huang, K., & Pearlson, K. (2019). For What Technology

Can't Fix: Building a Model of Organizational

Cybersecurity Culture. Proceedings of the 52nd Annual

Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

6398-6407.

IBM. (2022). Cost of a Data Breach 2022,. IBM.

https://www.ibm.com/reports/data-breach

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

268

Jalali, M. S., Russell, B., Razak, S., & Gordon, W. J. (2019).

EARS to cyber incidents in health care. Journal of the

American Medical Informatics Association, 26(1), 81-

90.

Kertysova, K., Frinking, E., van den Dool, K., Maričić, A.

and Bhattacharyya, K. (2018). Cybersecurity: Ensuring

awareness and resilience of the private sector across

Europe in face of mounting cyber risks. European

Economic and Social Committee. https://www.eesc.eu

ropa.eu/sites/default/files/files/qe-01-18-515-en-n.pdf

Keskin, O.F., Caramancion, K.M., Tatar, I., Raza, O., &

Tatar, U. (2021). Cyber third-party risk management: A

comparison of non-intrusive risk scoring reports.

Electronics, 10(10), 1168.

Knight, R., & Nurse, J.R.C. (2020). A framework for

effective corporate communication after cyber security

incidents. Computers & Security, 99. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.cose.2020.102036.

Manley, B.M. and McIntire, D. (2020). A Guide to

Effective Incident Management Communications.

Carnegie Mellon University.

Naseer, A., Naseer, H., Ahmad, A., Maynard, S.B., &

Siddiqui, A.M. (2021). Real-time analytics, incident

response process agility and enterprise cybersecurity

performance: A contingent resource-based analysis.

International Journal of Information Management, 59.

NIST. (2011). Information Security Continuous Monitoring

(ISCM) for Federal InformationSystems and

Organizations, NIST Special Publication 800-137,

National Intitute of Standards and Tecnology,

September 2011. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/

Legacy/SP/nistspecialpublication800-137.pdf

NIST. (2023). Public Draft: The NIST Cybersecurity

Framework 2.0. National Intitute of Standards and

Tecnology. 8 August 2023. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/

nistpubs/CSWP/NIST.CSWP.29.ipd.pdf

Quader, F. and Janeja, V.P. (2021). Insights into

organizational security readiness: Lessons learned from

cyber-attack case studies. Journal of Cybersecurity and

Privacy, 1(4), 638-659.

Rajan, R., Rana, N.P., Parameswar, N., Dhir, S., Sushil, and

Dwivedi, Y.K. (2021). Developing a modified total

interpretive structural model (M-TISM) for

organizational strategic cybersecurity management.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 170.

Ruefle, R., Dorofee, A., Mundie, D., Householder, A. D.,

Murray, M., & Perl, S. J. (2014). Computer security

incident response team development and evolution.

IEEE Security & Privacy, 12(5), 16-26.

Safitra, M.F., Lubis, M., & Fakhrurroja, H. (2023).

Counterattacking Cyber Threats: A Framework for the

Future of Cybersecurity. Sustainability, 15(18), 13369.

Serrano, M.A., Sánchez, L.E., Santos-Olmo, A., García-

Rosado, D., Blanco, C., Barletta, V.S., Caivano, D., &

Fernández-Medina, E. (2023). Minimizing incident

response time in real-world scenarios using quantum

computing. Software Quality Journal. https://doi.org/

10.1007/s11219-023-09632-6

Shinde, N., & Kulkarni, P. (2021). Cyber incident response

and planning: a flexible approach. Computer Fraud &

Security, 2021(1), 14-19.

Verizon. (2022). DBIR Data Breach Investigations Report.

Verizon Business.

Wertheim, S. (2019). Auditing for cybersecurity risk. The

CPA Journal, 89(6), 68-71.

Yusif, S., & Hafeez-Baig, A. (2021). A conceptual model

for cybersecurity governance. Journal of applied

security research, 16(4), 490-513.

Cybersecurity Incident Response Readiness in Organisations

269