Android App for Symptomatic Monitoring of Cervical Dystonia:

Design and Usability Study

Roland Stenger

1,∗ a

, Rica Schulze

1,∗

, Sebastian L

¨

ons

2

, Tobias B

¨

aumer

2

and Sebastian Fudickar

1 b

1

MOVE Junior Research Group, Institute of Medical Informatics, University of L

¨

ubeck, 23562 L

¨

ubeck, Germany

2

Institute for Systems Motor Science, CBBM, University of L

¨

ubeck, 23562 L

¨

ubeck, Germany

Keywords:

Smartphone App, Cervical Dystonia, Telemedicine, Asynchronous Video Recording.

Abstract:

Movement disorders are characterized by paucity or excess of movement. Access to specialists is difficult for

patients living in rural areas, making regular visits for symptom monitoring inconvenient. Asynchronous video

recording represents a telemedicine approach with temporal freedom but holds the challenge that clinicians

and patients can’t interact with each other and thus can’t correct errors, which can lead to a decrease in data

quality. This article presents an android application (Move2Screen) that aims to enable asynchronous therapy

monitoring and addresses the problem of missing interaction by an implemented video protocol for guided

recording to capture visible symptoms in the example of cervical dystonia. The videos can be accessed by

clinicians subsequent to an automated upload. A user study of the app was conducted, indicating a strong

interest and acceptance rate with a high willingness to use the app. Furthermore, the app can be used to

record a standardized data set, which allows a large number of patients to be reached without great effort by

clinicians and also provides the possibility of a semi-automated video-based analysis of current symptoms and

the longitudinal symptom progression.

1 INTRODUCTION

Movement disorders are a group of neurological

disorders, that present with involuntary movements.

They are caused by a variety of diseases, such as

Parkinson disease, Tourette syndrome, Huntington’s

disease, or dystonia. A distinction is made between

hypokinetic and hyperkinetic movement disorders.

Hypokinetic movement disorders such as Parkinson’s

disease are associated with a paucity of movement,

whereas hyperkinetic movement disorders such as

dystonia are marked by an excess of movement.

This article presents an app for therapy monitoring

through the example of cervical dystonia (the most

common form of dystonia). Dystonia is characterized

by abnormal, sustained muscle contractions that re-

sult in twisting or contorting of one or multiple joints.

It can manifest in different body areas, such as the

neck (cervical dystonia), eyelids (blepharospasm) or

the larynx (spasmodic dysphonia as a type of focal

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7590-7286

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3553-5131

∗

Authors contributed equally

dystonia). Dystonia can be classified into focal, seg-

mental, with tremor or generalized forms. For exam-

ple, “writer’s cramp” is focal hand dystonia, while

segmental dystonia involves two or more continu-

ous body regions. Generalized or multifocal dystonia

impacts multiple body parts simultaneously (Gerpen,

2013).

Cervical dystonia is usually diagnosed and treated

by specialists. However, access can be difficult and

costly, due to the limited number of movement dis-

order specialists, movement limitations, underserved

areas, and long travel distances (Ben-Pazi et al.,

2018)(Srinivasan et al., 2020). However, it is impor-

tant to monitor the progress of therapy regularly, as

the severity of cervical dystonia may change over time

and/or as a result of therapy. Cervical dystonia is of-

ten treated with botulinum toxin injections, where it

is common to receive such injections approximately

every 12 to 16 weeks (Ospina Medical, 2023). Con-

tinuous monitoring has potential benefits because the

effects of the injection vary from patient to patient and

side effects that may be caused by high doses can be

detected and corrected on an individual basis.

Telemedicine interventions such as (synchronous)

Stenger, R., Schulze, R., Löns, S., Bäumer, T. and Fudickar, S.

Android App for Symptomatic Monitoring of Cervical Dystonia: Design and Usability Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0012465300003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 2, pages 201-207

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

201

videoconferencing, which are already being increas-

ingly used (Ben-Pazi et al., 2018), may be able to

address these problems. It was found by (Hassan

et al., 2018) that 50% of Movement Disorder Soci-

ety members, mostly physicians, from 83 countries

around the world already use and plan to continue us-

ing telemedicine interventions such as videoconfer-

encing and video education in the context of move-

ment disorders. In addition, (Ben-Pazi et al., 2018)

has shown that Parkinson’s patients are satisfied with

a video consultation or even prefer it to a face-to-

face consultation. A study of telemedicine visits for

dystonia came to the same conclusions (Fraint et al.,

2020). Another study used web-based videoconfer-

encing to administer the MoCA test to subjects with

Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease and concluded

that administration was feasible with only minor tech-

nically related problems (Abdolahi et al., 2014).

While (Ben-Pazi et al., 2018) sees synchronous

videoconferencing as an improvement, (Srinivasan

et al., 2020) points out that asynchronous methods

can overcome the problems of poor internet connec-

tions, low resolution, and possible time management

problems due to the need for scheduling. In addition,

asynchronous methods are suitable for a longer-term

exchange, because patient and doctor do not have to

make an appointment every time and are more flexible

in their time management.

However, telemedicine via asynchronous videos

also holds challenges. Information gain is not as good

with asynchronous video because clinician and pa-

tient can not interact. (Srinivasan et al., 2020) sees

the problem that, some features in dystonic disorders

can only be detected through task-specific and in site-

specific situations. Furthermore, the article empha-

sizes that the quality of telemedicine analysis may de-

pend on the correct camera angle and good lighting.

This article presents the Move2Screen app, which

aims to overcome such problems in the example of

cervical dystonia. The app allows patients to record

guided videos at home. In these videos, they per-

form specific movements following a protocol, de-

signed to enhance the detection and assessment of

dystonia-specific symptoms. Guided positioning in

front of the camera and movement instructions are

displayed through an avatar, who imitates the desired

movements. The application is asynchronous, so the

patient can record videos at any time, overcoming the

need for a face-to-face appointment. The integrating

of a video protocol that guides the patient through the

recording process, is intended to overcome the chal-

lenges that arise from the lack of interaction in asyn-

chronous recordings. The video protocol ensures that

patients perform standardized movements so that the

clinician can identify and assess symptoms and com-

pare multiple videos at the same time stamps. In ad-

dition, the app allows patients to complete a question-

naire about their general well-being. This should pro-

vide the clinician with information about the patient’s

condition and the effect of the therapy.

Following, the app is introduced in detail. First, in

Section 2.1 the requirements of the app are discussed.

Then, the framework of the app is presented in Sec-

tion 2.2. While the app is still a research prototype,

we present the results of a first user study in Section 3.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Requirements of the App

Having previously discussed the advantages and dis-

advantages of telemedicine methods, we now want to

discuss the requirements for the app. Given the user

group that is to use the app and the sensitivity of the

data, we identify two particularly important require-

ments that the app must fulfill.

Ease of Use: As an asynchronous method, user-

friendliness is particularly important from the user’s

point of view, as it is not possible to respond quickly

and individually to problems and ambiguities when

using the app. Smartphone use is increasing in all

age groups. Cervical dystonia often starts between

30 and 50 years of age, whereas dystonia in cranial

regions first appears in the fifth or sixth decade of

life (Martino et al., 2012). Especially for this reason,

it is important to make the app as simple and intu-

itive as possible, so that users who have little knowl-

edge of smartphones can utilize the app without any

problems. Through the user experience study, we are

able to evaluate the simplicity of the app, which is dis-

cussed in section 3. Another related aspect regarding

ease of use is satisfaction, which is also addressed in

the usability study. According to (Liew et al., 2019)

is this based on their study the most important aspect

of health and wellness mobile apps.

Data Protection/Privacy: Person-identifying video

recordings can be considered very sensitive data, es-

pecially when the aim is to record a visible disease.

To prevent discomfort that might come from uncer-

tainty about how the data is processed and its location,

it is important to maintain transparency. Regarding

the importance of data security, (McGraw and Mandl,

2021) emphasizes that depending on health-related

data is used can yield positive or negative effects for

both individuals and entire populations. Unauthorized

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

202

access could lead to embarrassment and discrimina-

tion. Furthermore, the article mentions transparency

as an important point to encourage people to pro-

vide personal medical data. Before each upload to

a server for clinicians to view, users should always

know which data has been uploaded and retain full

control over the uploading process. We expect that the

app will be more widely accepted if users can delete

the data as quickly and easily as possible if they wish

to do so and the data is taken with care. Therefore,

we encrypt all data before it is uploaded. The data is

stored on a password-protected server that can only

be accessed by medical professionals or those who

have the login password and private key to decrypt

the data. The study showed that the respondents were

least likely to agree with the statement that they don’t

mind using the app in social settings compared to all

other responses. This emphasizes our point about the

importance of data security.

2.2 The Framework of the App

In the following, the features of the app are intro-

duced.

General Aspects: The framework is developed with

Android Studio and is designed for smartphones with

Android 8.0 or higher. It uses standardized functional

graphical units and will be familiar to Android users,

which increases intuitive usage.

Login: On the first start, the user logs in with a QR

code, which encodes an individual user ID. The ID is

then later used to pseudonymize the data.

Main Page: The app implements a bottom naviga-

tion with two tiles, one for video recording, and the

other one for the questionnaire, as shown in Figure 1.

Both pages have a main button, which starts the video

recording process or the questionnaire. A bordered

window shows the date of the last data recording and

the date of the next planned recording. For fine-scale

data collection, we consider weekly collection as a

good compromise between adequacy and collection

frequency.

In order to give the user the knowledge of which

data is already recorded and if it is uploaded (con-

sidering the data protection requirement mentioned

above), the app provides on both pages, the video

recording- and questionnaire- page navigation to-

wards a history page, which list all video recordings

or questionnaires respectively. The user can delete the

data and see which data is already uploaded. If it is

already uploaded, only the local file will be deleted to

save storage space. On the same history page, the user

Figure 1: Screenshots of the main pages of the app. The

video recording page is on the left side and the question-

naire page is on the right.

is able to watch the recorded videos or all given an-

swers to the questionnaires. Both pages are directly

accessible through the main page, as visible in Fig-

ure 1 through the buttons video overview and history

overview.

Video Recording and Questionnaire: When click-

ing on the button “neue Aufnahme” (new recording),

the user is guided through a preparation page, which

can be seen in Figure 2. This includes instructions

about positioning, background, and volume control

and gives the option to look through all the follow-

ing instructions within the video protocol or watch

an example recording of such video protocol. This

feature is optional since the instructions are spoken

out by the app and tests on subjects have shown a

good intuitive understanding. As the instructions are

adapted to typical movements for assessment of the

specified disease, the patient might be familiar with

them. The second preparation page shows the cam-

era view and the user sees him/herself. A human sil-

houette is drawn as an overlay to the camera view of

the user to show the correct positioning. The user

is instructed to position the camera so that the head

and shoulders are clearly visible, as cervical dystonia

affects the muscles in the head and neck. The user

can then start the recording by clicking on a button

at the bottom of the page. The recording is stopped

automatically after the last instruction. Directly after

the protocol finishes, the user can decide if the video

should be uploaded or deleted.

Android App for Symptomatic Monitoring of Cervical Dystonia: Design and Usability Study

203

Menu Button: The menu button on the main page

provides access to the privacy policy, instructions for

use, and information about the app in general and its

goals. The privacy policy has to be accepted with the

first login to the app and contains information on how

the data is handled as well as contact information of

the responsible data protection office of the Univer-

sity of L

¨

ubeck.

Tutorial Video

Figure 2: The two preparation pages before the guided

video recording, which contain confirmation buttons for

some necessary preparations a test button for the volume

on the first page, and a camera view for positioning on the

second page.

To help with questions about using or understanding

the app, we have created a tutorial video for each as-

pect of the app. These points explain both the oper-

ation and the purpose/idea of the app. The following

individual topics are covered by tutorial videos and

can be accessed via the menu under the Instructions

for use tab.

• Idea of the app

• Start page

• Menu

• Questionnaire

• Video recording

2.3 User Experience Study

A user experience study was conducted with a total of

10 participants, five of whom had symptoms of cer-

vical dystonia. The remaining five participants had

no symptoms. The purpose of the study was to test

the acceptance and usefulness of the app. In the first

part of the study, the participants were asked to navi-

gate through the app and then,find out how to record

a video. After navigating to the video recording page,

the participants were asked to record a video accord-

ing to the implemented protocol as second part of

the study. Participants were then asked to fill out a

questionnaire about the app. The questionnaire con-

sists of an adapted version of the German mHealth

App Usability Questionnaire (G-MAUQ) (Zhou et al.,

2019)(Kopka et al., 2023), general questions about

the age, gender, and experience with smartphones,

and several free text questions aiming for the subjec-

tive impression. The questionnaire is appended. The

last two question of the G-MAUQ where discarded,

as 3 to 4 of the diseased subjects gave an answer at

all to these questions. Each item of a total of re-

maining 16 items of the G-MAUQ was evaluated on

a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to

7 (strongly agree). The Q-MAUQ covers three sub-

scales: ease of use (5 items), interface and satisfac-

tion (7 items) and usefulness (4 items) which will be

evaluated separately.

3 STUDY RESULTS

In this section, the results of the user study are pre-

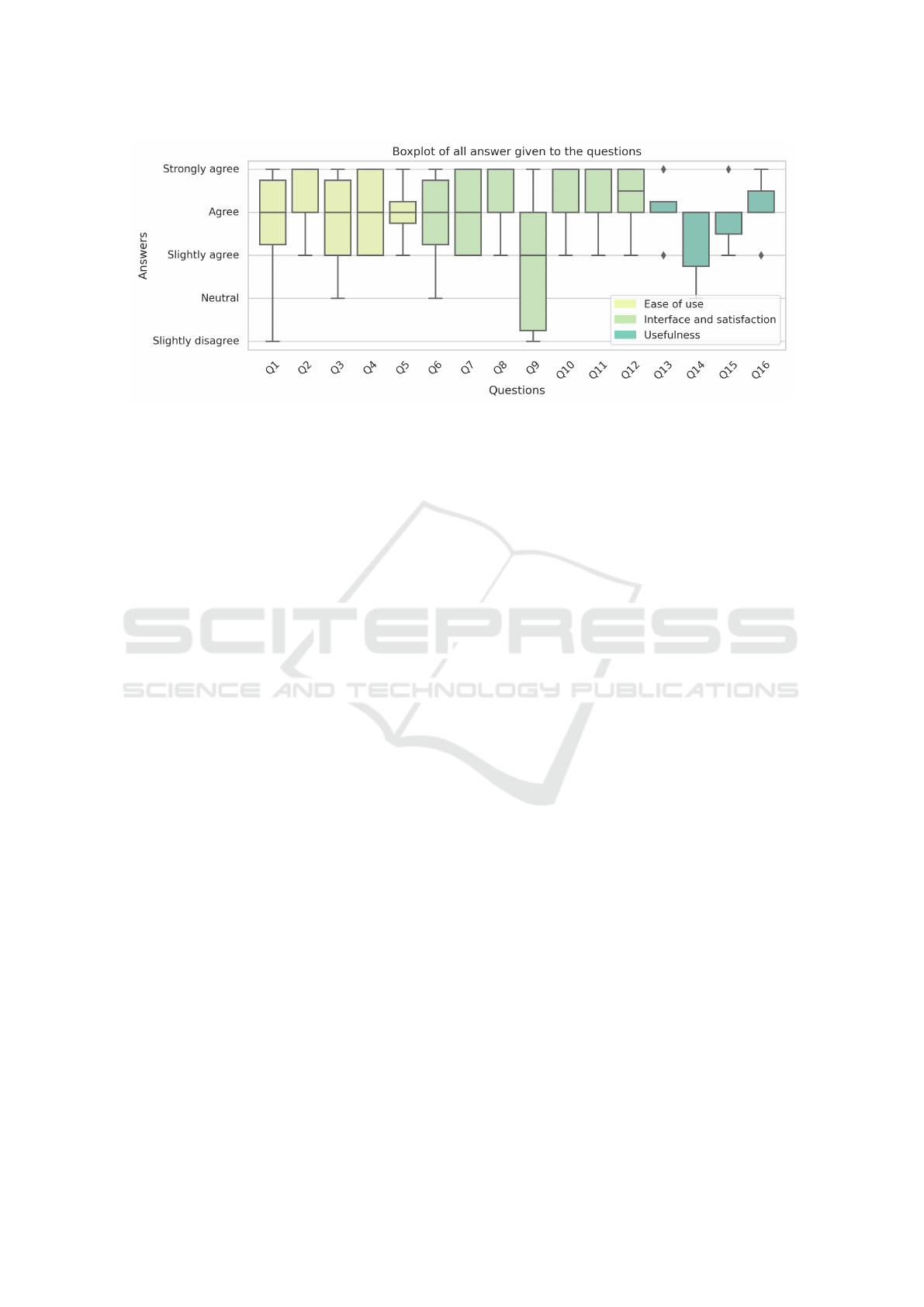

sented. In Figure 3 the answers to the G-MAUQ are

shown. The answers are sorted into the three groups

ease of use (E), interface and satisfaction (I) and use-

fulness (U). The answers are given in a range be-

tween 1 and 7, where 1 means strongly disagree and

7 strongly agree. In 75% of cases, the answers given

were 6 or 7 (agree or strongly agree), showing a high

acceptance of the app. The average value over all par-

ticipants and question groups are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Average values of the answers to the G-MAUQ.

Group Subjects Avg. (Std) Min/Max

E

Diseased 6.27 (±1.01) 4/7

Healthy 5.64 (±0.79) 3/7

I

Diseased 6.09 (±1.16) 3/7

Healthy 5.89 (±0.92) 3/7

U

Diseased 5.7 (±1.0) 4/7

Healthy 5.95 (±0.59) 5/7

The answers to question 9 (Q9: I feel comfort-

able using this app in social settings) stand out here,

as an average value of 4.8 (±1.6) was given. This

result emphasizes that video recording of oneself, es-

pecially with the aim of recording symptoms, is an in-

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

204

Figure 3: Boxplot of the answers to the G-MAUQ, sorted into the three groups ease of use, interface and usefulness.

timate matter. Question 14 (Q14: The app improved

my access to health care services.) was answered with

an average value of 5.4 (±0.9), and in two cases the

question was left unanswered. We assume that such

matter comes due to the fact, that the app was tested

in the setting of the study, which was not intended

to present a finished medical product, but merely to

serve as a test phase, without any advantages for the

diseased test subjects. For questions 11 to 16, at least

two and at maximum three times, an answer was not

given.

Additional to the G-MAUQ question, several text

questions were asked as well (see appendix questions

22-26) and a discussion was held on the general im-

pression of the app. Individual uncertainties regarding

operation were expressed. The steps to counter these

ambiguities are listed below, to name a few:

• The bottom navigation was colored to make it

more visible.

• Text was added under the back-arrow, to make it

more clear that it is a back button.

• One prerequisite was that the test subjects remove

their glasses in order to collect the data more uni-

formly. This requirement was discarded due to a

comment from a subject

• Within the video protocol, it was not clear in

which direction the subject should rotate as part

of the tasks. This was changed by adding a clearer

vocal instruction.

• The silhouette that is used to show the correct po-

sitioning of the camera was not in a realistic shape

of a human. This was changed to a more realistic

shape (visible in Figure 2)

4 DISCUSSION

This paper presents asynchronous therapy monitoring

app for cervical dystonia in order to create standard-

ized videos that may help clinicians to derive a quali-

tative severity score. The app is designed for the mon-

itor the progression of cervical dystonia, but it could

be adapted to other movement disorders. First results

from patients with cervical dystonia and a healthy

control group indicate a high interest in the app based

on the good results of the G-MAUQ. Good results in

the qualitative user study groups Ease of use and In-

terface and satisfaction of the G-MAUQ, which both

scored with a rating of over 6 (agree) of the dis-

eased participants, underline the user-friendliness of

the app. The question group Usefulness scored with

a rating of 5.7 (agree) of the diseased participants,

which is slightly below the global average of 5.94

(±0.96) and several questions in this group were not

answered by each subject, so the data base on which

this result is based is smaller than for the other ques-

tion group. We hypothesize that this result was in-

fluenced by the context of the study. The app was

evaluated during a test phase, not as a complete med-

ical product. Consequently, this trial phase did not

provide any direct benefit to the participants suffer-

ing from dystonia, which could then influence the per-

ceived usability.

The results of the study show the interest in the

app and the amount of participants (10 individuals

where 5 are diseased and 5 healthy) is sufficient in our

estimation, as the comments did not differ much from

each other except for some minor navigation difficul-

ties and a saturation of findings was reached¡ (Sauro

and Lewis, 2012). However, not all subjects gave an

answer to all questions, which shrinks the cohort on

some questions. The short duration of the usability

Android App for Symptomatic Monitoring of Cervical Dystonia: Design and Usability Study

205

study does not encompass the engagement and effi-

cacy when the app is used for a long period and from

home.

5 CONCLUCION

Our initial short-term usability study with a sample

size of 10 participants showed promising results in

terms of user acceptance and willingness to use the

app. However, we acknowledge the limited duration

of the individual subject tests of the app which can-

not replace a study lasting several weeks. Although

initial responses regarding usability are encouraging,

further research is needed to investigate the clinical

efficacy of the application. We aim to conduct a more

comprehensive study with a larger and more diverse

cohort to test the reliability and acceptance of the

application for independent use over a 12-week pe-

riod. This longer period will allow us to determine the

level of acceptance of the app more clearly, as it re-

quires more initiative to use independently. Subjects

must invest time on a weekly basis without receiv-

ing immediate feedback. Regarding these aspects, we

expect that some questions of the G-MAUQ will be

more meaningful in the context of the planned study.

Furthermore, the quality of the uploaded videos will

also be evaluated for their medical usefulness. The

app’s fundamental purpose is to document the pro-

gression of symptoms over several weeks. The videos

recorded in the planned study provide a data set that

allows for comparison of the same time stamps be-

tween videos of the same person over a period of

multiple weeks, enabling an accurate assessment of

symptom progression. The implemented video pro-

tocol ensures fixed time points at which the same

movement is performed. This standardized evaluation

would not be possible without such a video protocol

as it is implemented in the app

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thank all participants of the user study

for their time and effort. We acknowledge financial

support by the German Federal Ministry of Education

and Research (01ZZ2007).

REFERENCES

Abdolahi, A., Bull, M. T., Darwin, K. C., Venkatara-

man, V., Grana, M. J., Dorsey, E. R., and Biglan,

K. M. (2014). A feasibility study of conducting the

montreal cognitive assessment remotely in individuals

with movement disorders. Health Informatics Jour-

nal, 22(2):304–311.

Ben-Pazi, H., , Browne, P., Chan, P., Cubo, E., Guttman, M.,

Hassan, A., Hatcher-Martin, J., Mari, Z., Moukheiber,

E., Okubadejo, N. U., and Shalash, A. (2018). The

promise of telemedicine for movement disorders: an

interdisciplinary approach. Current Neurology and

Neuroscience Reports, 18(5).

Fraint, A., Stebbins, G. T., Pal, G., and Comella, C. L.

(2020). Reliability, feasibility and satisfaction of

telemedicine evaluations for cervical dystonia. Jour-

nal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(9):560–567.

Gerpen, J. A. V. (2013). Marsden's book of movement dis-

orders. Neurology, 80(24):2278–2278.

Hassan, A., Dorsey, E. R., Goetz, C. G., Bloem, B. R.,

Guttman, M., Tanner, C. M., Mari, Z., Pantelyat, A.,

Galifianakis, N. B., Bajwa, J. A., Gatto, E. M., and

Cubo, E. (2018). Telemedicine use for movement dis-

orders: A global survey. Telemedicine and e-Health,

24(12):979–992.

Kopka, M., Slagman, A., Schorr, C., Krampe, H., Al-

tendorf, M. B., Balzer, F., Bolanaki, M., Kuschick,

D., M

¨

ockel, M., Napierala, H., Scatturin, L., Schmidt,

K., Thissen, A., and Schmieding, M. (2023). Ger-

man mHealth app usability questionnaire (g-MAUQ):

Translation and validation study. Center for Open Sci-

ence.

Liew, M. S., Zhang, J., See, J., and Ong, Y. L. (2019).

Usability challenges for health and wellness mobile

apps: Mixed-methods study among mhealth experts

and consumers. JMIR MHealth UHealth, 7(1).

Martino, D., Berardelli, A., Abbruzzese, G., Bentivoglio,

A. R., Esposito, M., Fabbrini, G., Guidubaldi, A.,

Girlanda, P., Liguori, R., Marinelli, L., Morgante,

F., Santoro, L., and Defazio, G. (2012). Age at on-

set and symptom spread in primary adult-onset ble-

pharospasm and cervical dystonia: Age and spread in

primary adult-onset dystonia. Movement Disorders,

27(11):1447–1450.

McGraw, D. and Mandl, K. D. (2021). Privacy protections

to encourage use of health-relevant digital data in a

learning health system. npj Digital Medicine, 4(1).

Ospina Medical (2023). Conquering cervical dystonia:

The power of intramuscular botox injections. [2023,

April 19] https://ospinamedical.com/orthopedic-

blog/conquering-cervical-dystonia-the-power-of-

intramuscular-botox-injections.

Sauro, J. and Lewis, J. R. (2012). Chapter 2 - quantifying

user research. In Sauro, J. and Lewis, J. R., editors,

Quantifying the User Experience, pages 9–18. Mor-

gan Kaufmann, Boston.

Srinivasan, R., Ben-Pazi, H., Dekker, M., Cubo, E.,

Bloem, B., Moukheiber, E., Gonzalez-Santos, J., and

Guttman, M. (2020). Telemedicine for hyperkinetic

movement disorders. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic

Movements, 10(0).

Zhou, L., Bao, J., Setiawan, I. M. A., Saptono, A., and

Parmanto, B. (2019). The mHealth app usability

questionnaire (MAUQ): Development and validation

study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(4):e11500.

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

206

APPENDIX

Questionaire

The questionaire consists of the G-MAUQ and addi-

tional questions which are listed below. The MAUQ

question which we use for our study were translated

into German and validated by (Kopka et al., 2023).

Ease of Use (MAUQ)

Q1. The app was easy to use.

Q2. It was easy for me to learn to use the app.

Q3. The navigation was consistent when moving

between screens.

Q4. The interface of the app allowed me to use all the

functions (such as entering information, responding

to reminders, viewing information) offered by the

app.

Q5. Whenever I made a mistake using the app, I

could recover easily and quickly.

Interface and Satisfaction (MAUQ)

Q6. I like the interface of the app.

Q7. The information in the app was well organized,

so I could easily find the information I needed.

Q8. The app adequately acknowledged and provided

information to let me know the progress of my action.

Q9. I feel comfortable using this app in social

settings.

Q10. The amount of time involved in using this app

has been fitting for me.

Q11. I would use this app again.

Q12. Overall, I am satisfied with this app.

Usefulness (MAUQ)

Q13. The app would be useful for my health and

well-being.

Q14. The app improved my access to health care

services.

Q15. The app helped me manage my health effec-

tively.

Q16. This app has all the functions and capabilities I

expect it to have.

General Questions

Q17. Age

Q18. Gender

Q19. Do you have any experience with smartphones?

(on a scale 1-5)

Q20. How often do you use your smartphone? (less

than 1x per week, multiple times per week, daily)

Q21. What do you use your smartphone for? (phone

calls, chat/social media, gaming, streaming, internet

research, organization)

Free Text Questions

Q22. For which functions unexpected errors have

occurred?

Q23. What about the app did you not understand or

find it too complicated?

Q24. Which functions did you miss?

Q25. Which functions do you find superfluous?

Q26. Do you have any further comments or sugges-

tions for improving the app?

Android App for Symptomatic Monitoring of Cervical Dystonia: Design and Usability Study

207