Chatting for Change: Insights into and Directions for Using Online

Peer Support Groups to Interrupt Prolonged Workplace Sitting

Ekaterina Uetova

1a

, Lucy Hederman

2b

, Dympna O’Sullivan

1c

, Robert Ross

1d

and Marily Oppezzo

3e

1

School of Computer Science, Technological University Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

2

School of Computer Science and Statistics, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

3

Department of Medicine, Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, U.S.A.

Keywords: Behavior Change, Peer Support, Sedentary Behavior, Mobile Health.

Abstract: Prolonged sedentary behavior and insufficient physical activity increase the risk for non-communicable

diseases. Online peer support groups, driven by the widespread use of mobile phones and social media, have

gained popularity among people seeking health condition management advice. This position paper examines

the role of online peer support groups within a behaviour change intervention, MOV’D (Move Often eVery

Day), which promotes physical activity and reduces sedentary behavior in the workplace. We conducted a

thematic analysis of post-study interviews from two randomized control trials to identify the benefits and

limitations of online peer support groups and provide recommendations for improvement. We found that

participation in online peer support groups contributes to a sense of belonging and accountability, helps to

facilitate the exchange of knowledge and application of the intervention content, and serves as reminders

encouraging physical activity throughout the day. However, participants do not always have enough time and

cognitive resources to read all the messages and actively participate in the group chats. Individual differences

also contribute to a decrease in overall chat activity, as the group chat does not always meet all participant’s

preferences and needs.

1 INTRODUCTION

Peer support has proven to be invaluable in helping

many people overcome difficult situations and is often

defined by the ability of people with similar life

experiences to establish deeper connections, offer

more authentic empathy and validation and provide

practical advice that professionals may not know

about (Mead & MacNeil, 2006). In recent years, with

the widespread use of mobile phones and social

media, online peer support groups (OPSG) have

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-9605-9616

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6073-4063

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2841-9738

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7088-273X

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6668-2508

1

Sedentary behavior refers to any waking activities

characterized by an energy expenditure equal to or below

1.5 metabolic equivalents (METs) while in a sitting,

reclining, or lying posture; prolonged sedentary behavior

refers to accumulation of sedentary behavior in extended

continuous bouts (Tremblay et al., 2017).

gained popularity among those who are seeking

advice on the management of physical and

psychological health conditions and have

demonstrated a number of benefits, such as protecting

from social stigma, decreasing loneliness and anxiety,

facilitating feelings of empowerment, boosting

general well-being and providing better opportunities

for self-expression (Iliffe & Thompson, 2019).

One of the areas where peer support groups can be

applied is occupational health. A common workplace

problem is prolonged and uninterrupted sedentary

behavior

1

(Wu et al., 2023). Office workers have been

166

Uetova, E., Hederman, L., O’Sullivan, D., Ross, R. and Oppezzo, M.

Chatting for Change: Insights into and Directions for Using Online Peer Support Groups to Interrupt Prolonged Workplace Sitting.

DOI: 10.5220/0012423400003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 2, pages 166-174

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

reported to be sedentary for 81.8% of work hours on

work days, with much of this time spent in prolonged

uninterrupted bouts

2

of longer than 30 minutes (Parry

& Straker, 2013). Moreover, individuals who were

most sedentary at work were found to be also more

sedentary outside work (Parry & Straker, 2013),

which could potentially result in an overall daily

sedentary time

3

ranging from 7.7 to 11.5 hours per

day (Dunstan et al., 2021). People can meet physical

activity recommendations for their age but still spend

a substantial part of their day sedentary (Dunstan et

al., 2021), and therefore still be at risk for the

development of diseases such as type II diabetes,

cardiovascular diseases, abdominal obesity,

metabolic syndrome, and premature mortality

(Dunstan et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2023). A growing

body of evidence suggests that reducing sedentary

behavior and breaking up prolonged sitting not only

enhances the health and well-being of employees

(Radwan et al., 2022) but also improves social

interaction and work performance (Damen et al.,

2020; Radwan et al., 2022).

According to reviews that have assessed

interventions targeting sedentary behavior and

physical activity in workplace contexts, one of the

most promising and frequently used techniques was

creating social support (Damen et al., 2020). The focus

group study that investigated factors influencing the

adoption of workplace activity breaks identified

workplace culture and awareness of the activity breaks

benefits as both facilitators and barriers: supportive

workplace cultures and knowledge of the benefits

were seen as facilitators, while cultures inhibiting

breaks and lack of awareness were barriers

(Hargreaves et al., 2020). Another study among full-

time working adults examined the extent and type of

social support for physical activity from coworkers,

friends and family and discovered that coworker

support was the sole source significantly associated

with physical activity, emphasizing the importance of

incorporating coworker social support in workplace

health promotion programs (Sarkar et al., 2016).

We know workplace culture and social norms can

be a barrier and social support can be a facilitator. The

qualitative study on employee preferences for

workplace health promotion highlighted the

significance of virtual social connections in an online,

asynchronous setting (Olsen et al., 2018). Given this,

it becomes evident that there is a need to identify what

role OPSG can play in workplace interventions to

interrupt prolonged sitting. The primary aim of this

2

Sedentary bout is a period of uninterrupted sedentary

time (Tremblay et al., 2017).

study was to address this gap and investigate the

benefits and barriers associated with OPSG by

conducting a thematic analysis of post-study

interviews from two randomized control trials with

adults employed in sedentary jobs.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study Design

This paper analyses data from a larger parent trial,

Move Often eVery Day, a randomized controlled pilot

to decrease sedentary behavior by interrupting

prolonged sitting with high intensity exercise snacks.

The study was approved by the Stanford University

Institutional Review Board (IRB-60388) and was

registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05360485).

This was a remotely-delivered study conducted from

April to September 2022 with participants recruited

from the United States. Inclusion criteria included: age

(>18 years), language (English-speaking), owning a

smartphone with internet access, being employed in

sedentary job and with ability to safely increase

physical activity. Informed consent was obtained from

all participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Consented participants were randomized in blocks of

20-24 to one of two groups: MOV’D, which included

an online peer support group and study materials; and

self-monitoring only, which received all study

materials at the end of the 2-month study. Participants

in each block were stratified by self-reported physical

activity from most to least active. Participants were

then randomized in blocks of four, with two “buddies”

within the MOV’D peer support group, and the two

others assigned to the control group with no

connection (Full protocol paper pending publication).

The MOV’D intervention included a private peer

support group which received once a week behavior

change strategy videos and every weekday exercise

snack videos (called a “snacktivity” in the study) and

intervention prompts to reinforce the exercise snack

behaviors and behavior change strategies taught in the

intervention (Chase et al., 2009; Leelawong et al.,

2002). Participants were given the option to select a

behavior change video from a provided list. They were

then encouraged to summarize the selected video to

their buddy in the group chat as a means of reinforcing

their understanding of the content. At the beginning of

the intervention, all the participants in the MOV’D

3

Sedentary time refers to the time spent for any duration

(e.g., minutes per day) in any context (e.g., at work or

home) in sedentary behaviors (Tremblay et al., 2017).

Chatting for Change: Insights into and Directions for Using Online Peer Support Groups to Interrupt Prolonged Workplace Sitting

167

condition met via Zoom to practice tweeting / group

messaging, practice a snacktivity, and learn about their

weekly behavior change videos and goal setting with

their buddies. Buddies met in breakout rooms during

this initial Zoom meeting.

At the beginning of the study, some participants

created private chats and used them as the main

channel to communicate with their buddy. At the one-

week check in point, a decision was made to direct all

messages to the group chat, allowing everyone to

engage in the activities and share in the learning

experience. This approach was adopted from the

Tweet2Quit buddy study (Pechmann et al., 2017) to

ensure that even those without great matches could

benefit from and observe the group's activities.

There were three cohorts within the MOV’D

study. The first cohort was Twitter-based, modelled

after the Tweet4Wellness (Oppezzo et al., 2021) and

Tweet2Quit studies (Pechmann et al., 2017). The

other two used GroupMe as a platform for online peer

support due to participants’ feedback from the first

study and API changes.

2.2 Data Collection and Analysis

In this study, we focused on data from cohorts 2 and

3 due to their similarities in utilizing GroupMe as

communication channel and audio-recordings of

post-study interviews. In contrast, Cohort 1 was based

on Twitter, and had only detailed notes rather than

audio-recordings of interactions.

The research team conducted semi-structured,

individual interviews with participants after the study

period via Zoom. Before each interview began, the

purpose of the interview was explained to the

participant, confidentiality was guaranteed,

permission to record the interview was asked and the

participant was invited to clarify or ask questions. The

interviews were systematically audio-recorded and

subsequently transcribed and checked for accuracy.

The analysis and results reporting format

followed guidelines for thematic analysis (Maguire &

Delahunt, 2017). We started with open coding, based

on recurring ideas and concepts found in the

interview transcripts. For this study, we only analysed

the parts of the interview that were related to the

online peer support group and buddy system. The

questions covered overall intervention experience,

e.g., “What was your overall experience with the

intervention?” and “Was there anything that stood out

as particularly enjoyable or beneficial to you?”, the

nature of the relationship with buddy, e.g., “Did you

have regular interactions with your buddy? Was that

a good connection?” and interaction with study

components, e.g., “What were your thoughts on the

behavior change videos? Was it helpful when you

shared with your buddy what you learned from these

videos?”. Codes were refined, merged, or split as

necessary to ensure accuracy and consistency. Codes

were then grouped together to develop the themes that

emerged from the data.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants Characteristics

This sub analysis looks at cohort 2 and 3 intervention

groups of the MOV’D study, and specifically the 9 of

25 participants who agreed to attend the post-study

interview. Demographics and other baseline

characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority

of participants in both cohorts worked full-time in a

hybrid work situation. Cohort 2 features the younger

age group (mean age of 37 years) with a relatively

balanced gender distribution (25% male, 67% female

and 8% non-binary). Cohort 3 represents an older age

group (mean age of 41.6 years) with a predominantly

female population (92%). Body mass index (BMI) for

each participant was calculated using a formula, BMI

= weight (lb) / [height (in)]

2

x 703, provided on the

CDC website based on self-reported weight and

height data. In Cohort 3, 12 participants out of 13

provided information about their weight and height.

In both cohorts, mean BMI score was within the

overweight range (CDC, 2022).

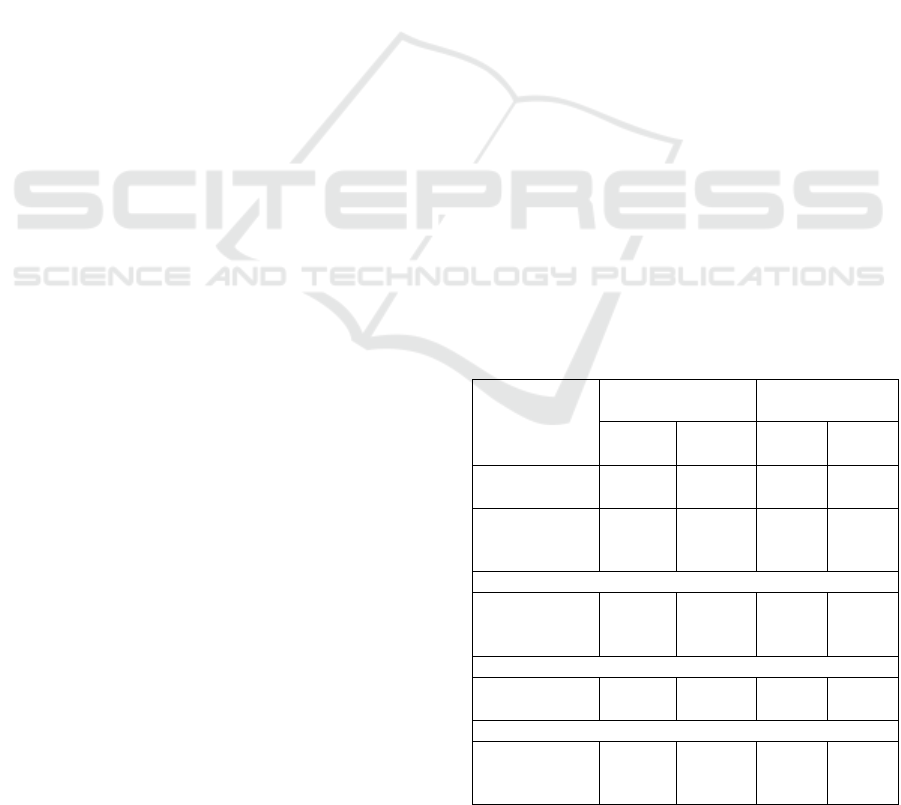

Table 1: Baseline characteristics by cohort.

Characteristics Intervention

groups

Interview

subgroups

C2

(n = 12)

C3

(n = 13)

C2

(n = 3)

C3

(n = 6)

Age (years),

mean (SD)

37

(9.1)

41.6

(10.7)

33.3

(0.6)

48.5

(9.4)

BMI (ib/in

2

),

mean (SD)

26.7

(6.8)

26.7

(9.8)

(

n = 12

)

25.5

(7.9)

28.6

(6.3)

Gender, n

(

%

)

Man

Woman

Non-

b

inar

y

3 (25)

8 (67)

1 (8)

1 (8)

12(92)

0 (0)

1 (33)

2 (66)

0 (0)

0 (0)

6(100)

0 (0)

Employment status, n (%)

Full-time

Part-time

12(100)

0

(

0

)

12 (92)

1

(

8

)

3(100)

0

(

0

)

5 (83)

1

(

17

)

Work situation, n (%)

From home

Office

Hybri

d

1 (8)

4 (33)

7 (58)

3 (23)

3 (23)

7 (54)

0 (0)

2 (66)

1 (33)

1 (17)

1 (17)

4 (66)

C2 – Cohort 2, C3 – Cohort 3.

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

168

3.2 Thematic Analysis

The thematic analysis resulted in the emergence of 6

themes, which we organized into two categories:

benefits and barriers (Table 2). Pseudonyms have

been used to protect the identity of the participants.

Each pseudonym consists of a single alphabetic

character representing gender (either "M" for male or

"F" for female), followed by a unique numerical

identifier allocated at the time of participant

registration, separated by an underscore character,

and concluding with a number indicating the

participant's cohort affiliation.

Table 2: Themes by category.

Categor

y

Themes

Benefits Accountabilit

y

and Motivation

Communit

y

and Connection

Pee

r

Learnin

g

Reminders

Barriers Time and Cognitive Resource Demands

Individual Differences

In the following we breakdown these themes and

present evidence in their support.

Benefits:

Theme 1: Accountability and Motivation

OPSGs provide participants with motivation and a

sense of accountability to the group and to their buddy

and support the commitment of the participants to

their physical activity goals: “It was encouraging just

in the GroupMe because we would tag each other and

say, ‘Hey, what'd you do today?’ or ‘How'd it go?’ or

if she [her buddy] said something I'd say, ‘Oh well

good job. Congratulations on what you're doing.’ So,

we were encouraging and pushing each other

forward. So, it was great.” (F57_3).

Even though some participants had doubts about

the use of social media before the study began, the

mode of interaction was still beneficial to them: “I'm

not big into social media in that type of way, but I

found that it helped me be more accountable, I think.”

(F36_3).

Theme 2: Community and Connection

Most participants valued the sense of community and

support they received from the OPSG members. The

group allowed them to discuss challenges, share

experiences and progress, and feel that they were not

alone in their efforts: “I just feel people was very

supportive in that group. For example, some people

mentioned that they didn't work out lot during the day,

and the group show some sympathy to that person. I

think on that day, I also didn't work out lot, so I feel

that that not really a bad day. That wasn't a bad day

for me.” (M51_2).

Several participants valued the opportunity for

face-to-face connections provided by Zoom meetings

before the study. They found it beneficial for

establishing connection with their buddy: “I

definitely felt like making that the personal Zoom

face-to-face connection was helpful. Otherwise to me

it's just like this nameless, well it's not a nameless, it's

a named but faceless person out there that I know

nothing about.” (F36_3).

Some participants noted that they did not consider

the group chat to be an important part of the study and

that it did not help them change their behavior, but

they believed it was nice to be in a group of people

who were going through the same things they were

going through: “I like the idea of the chat. I think it

was more fun than anything else. I don't think it really

changed my behavior, but hey, it's nice to talk to

people who are doing the same thing. So, I would

recommend keeping it.” (F73_3).

Theme 3: Peer Learning

Participants found value in reading about other

participants' ideas, tips and experiences, which aided

their own learning: “I guess one of the things I liked

about the group chat was that people also put on

other ideas for snacktivities. So, I'm not sure I would

have even thought about going to, let's say YouTube,

to look for other things. And so, I did my own searches

as well and found things. Some I felt were good and

some were not good, but at least it just made me look

around a little bit more.” (F36_3).

Participants mentioned that summarizing the

behavior change videos to their buddy helped

reinforce learning and understanding of the content:

“I think it is useful. I mean I definitely do because I

think that like me and like I say, things are not taking

residence in my memory because it's just too crowded

up there. But at least having to restate it makes me

think about it one more time.” (F36_3). Participants

also found it useful to read others’ video summaries:

“I think that the buddy restatement was helpful. It was

helpful for me because when I would read what videos

they read, I'd be like, oh, I think all the videos on a

weekly basis were kind of similar but a little bit

different. So, I was able to learn from other people

because I would read other people's summaries to

just see what they read or how their lesson was

different from my lesson.” (F57_3).

Chatting for Change: Insights into and Directions for Using Online Peer Support Groups to Interrupt Prolonged Workplace Sitting

169

Theme 4: Reminders

Participants perceived messages as reminders of their

commitments encouraging physical activity

throughout the day: “Whenever I would see the

GroupMe chat, it would bring me back to the study

and take my eyes away from my work to my phone and

remind myself about it, and so I think just that habit

of every few hours of seeing others update their

activity just kept that cycle in my brain of that break.”

(F68_2) and engagement with the study components:

“But as I said, as time went on it became like, oh

reminders, oh I got to do this. Oh, such and such

already read hers, let me read mine, let me send my

report, let me connect with my person. So, I liked the

dings and the reminders ...” (F57_3).

Barriers:

Theme 5: Time and Cognitive Resource Demands

Initially, certain participants perceived the OPSG as

an overwhelming responsibility due to the numerous

study components associated with it, all of which

were expected to be completed: “In the beginning I

think it kind of felt a little bit overwhelming because

it was like, man, I got to watch this video and then I

have to summarize it and then I have to tag my

person.” (F57_3).

Several participants mentioned the challenges

they had of being actively involved in the chat. They

did not always have enough time and cognitive

resources to read all the messages, reply to them, post

something about themselves: “By the time I get

around to it [group chat] I have to scroll so many.

And usually at that time I'm just skimming through.”

(F46_3). Sometimes it was difficult for participants to

remember to open the app as it was a separate one

which they were not used to using: “I use text

message more and I think having a separate app to

message on, it was easy for me to forget about it. So,

I think towards the end, if other people hadn't sent

something, I would forget that message had come

through.” (F72_2).

Some participants mentioned that they or their

buddies were not active in the group chat, and this

lack of engagement may have limited the overall

effectiveness of the group interaction: “So, I think my

buddy, I think, the connection was good, but I think

that she was struggling in a way, probably that I

couldn't help her. So, I would contact her in the chat,

and we would interact when she was able to chat. So,

she chatted a lot less than I did and was less engaged.

But when she did engage me, she did, I would tell her,

‘I hope you met your goal,’ and she would tell me that

she did and I would tell her what I had done for the

day, that kind of thing. But she wasn't as active, so it

wasn't every single day. It might go a few days to a

week even.” (F81_3) and caused a feeling of

isolation: “I think I didn't receive any message from

the supportive group. I think I just feel a little bit

isolated, maybe.” (M51_2).

Theme 6: Individual Differences

OPSG may not cater to individual preferences and

needs, potentially causing social pressure and guilt,

hindering support and overall desire to participate in

the group chat: “Yeah, I think I feel a little bit of

pressure that I need to, maybe, do something quite

equally with what my buddy did for the rest of the day.

[…] I think it's both positive and negative [peer

pressure]. Sometime, because I just feel I'm too tired

at the end of the day, but I want to, maybe that I don't

want to let my buddy down.” (M51_2).

Some participants expressed a preference for

direct messaging with their buddy and believed it

would be more effective than group interactions for

maintaining accountability and personal connections:

“I think having a little bit more of a personal

connection with my buddy would've been more

accountable and then more easier for me to check in

on her and be like, ‘Hey, did you get it done today?’

Rather than, I wouldn't want to say that in the group.

I feel like I'm shaming her, you know what I mean,

calling her out in the group, too.” (F68_2) and

completing study components: “So, the videos,

originally, I watch it pretty religiously. Because then

if I forget, if I don't see it, my buddy will remind me,

‘Hey did you watch this video?’ I'm like, ‘what

video?’ And I go find it. When we moved to a public

chat, all our discussions were all buried. And when

you get an alert, it's not very apparent. I have to go

find my buddy.” (F46_3).

However, they noted that direct messaging

experience depends on the buddy: “It really depends,

right? If you have a good buddy. The experience [of

direct messaging], depending on the kind of buddy

you have, the experience will probably be different,

right. I had a really good buddy.” (F46_3).

Participants expressed diverse attitudes towards

chat interactions. While some felt comfortable

engaging in group chat: “For me, it was easy to react

to every message.” (F61_3), others found it hard to

keep up: “For me it's kind of a hit and miss. I'll be

active one or two days and then I'll disappear and

vice versa. And so on the days where you see me pop

in on the public chat or the group chat are usually

days I might have more time or whatever.” (F46_3),

and some participants showed a preference for

offering help and support rather than receiving it

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

170

themselves: “I'm better at helping people do it

[receiving help or support] than I am for receiving it,

to be honest with you. And so, I don't get as much from

it as I might be helpful in giving it.” (F81_3).

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 General Discussion

This paper reports on a qualitative analysis of a subset

of post-study interview data collected after a

randomized controlled pilot of a remotely delivered

exercise snack intervention with a peer support

component, targeting adults with sedentary jobs to

promote physical activity and reduce sedentary

behavior in the workplace. The identified themes fall

into two categories: the benefits that the participants

derived from participating in the OPSG and

challenges they experienced.

Participation in OPSG was observed to have

several beneficial effects on the study participants,

consistent with prior literature (Delisle et al., 2017;

Iliffe & Thompson, 2019; Karusala et al., 2021). First,

OPSG gave participants the sense of belonging and

accountability that created a supportive and

motivational environment. Participants saw that

others experienced similar difficulties and felt that

they were not alone in their journey towards better

health and physical activity. This sense of community

provided motivation and encouragement, helping

participants stay on track with their physical activity

goals and driving participants to feel responsible not

only to themselves but also to the group and their

designated buddies.

Moreover, the OPSG became a peer learning

space where participants could share their

experiences, ask for help and advice, exchange

knowledge and ideas, as well as summarize the

behavior change videos that foster a deeper

understanding of the intervention content (Chase et al.,

2009; Leelawong et al., 2002). This knowledge sharing

allowed participants to gain insights, tips, and different

perspectives from their peers, ultimately enhancing

their own learning and reinforcing use of the behavior

change concepts introduced during the study.

Additionally, the OPSG played a role of

reminders, nudging participants to maintain their

commitment to physical activity. Participants noted

that group messages acted as prompts to break up

prolonged periods of sitting and engage in more

active behaviors. The constant presence of the group

chat facilitated a continuous awareness of their health

goals, reminding them to make healthier choices

throughout the day, even in a busy office

environment.

However, it is important to acknowledge that

despite the numerous benefits of OPSG, participants

do face some significant challenges that can affect

their ability to fully engage in the group chats and

harness the advantages (Karusala et al., 2021). One of

the primary challenges is the constraint of both time

and cognitive resources. Participants noted that

demanding work environment and personal

responsibilities make it challenging to dedicate the

necessary attention to OPSG: post their updates, read

and respond to other participants’ messages.

Moreover, some participants found it difficult to

remember to open the GroupMe app because they

were not used to using it. As a result of low

engagement of participants themselves and their

buddies, some people may have experienced feelings

of isolation from the group.

Furthermore, individual differences in

preferences and needs significantly influenced their

engagement in the OPSG. While some found it easy

to engage in group chat, maintaining a high level of

involvement, others experienced fluctuations in their

engagement, acknowledging that they might actively

participate for a few days, and then experience

periods of inactivity. Notably, participants'

perceptions of the group chat's significance also

differ. Some find it highly motivating and integral to

their behavior change goals, while others perceive it

as a secondary aspect that doesn't substantially affect

their progress. This discrepancy in perceptions

suggests that the group chat may not align with

everyone's communication preferences or objectives.

Moreover, some participants expressed a preference

for more personalized, one-on-one communication

with their designated buddies rather than with the

whole group. This preference could stem from

concerns about discussing their progress with a large

group of unfamiliar people (Smythe et al., 2022) or

feeling of peer pressure and the potential guilt

associated with not meeting physical activity

commitment. While some felt positively driven by the

desire to meet their weekly physical activity goals and

feeling of accountability, others found it burdensome

and sometimes guilt-inducing. These emotional

responses were often influenced by individual

characteristics and their perceptions of social

interactions within the group.

4.2 Limitations and Future Directions

While our study provides valuable insights into using

OPSG to reduce workplace sedentary behavior, it is

Chatting for Change: Insights into and Directions for Using Online Peer Support Groups to Interrupt Prolonged Workplace Sitting

171

essential to acknowledge certain limitations that may

influence the interpretation of our findings.

As the paper relies on self-reported data, it might

be subject to social desirability bias (Piedmont,

2014), i.e., participants might have reported what they

thought the researchers wanted to hear, especially

regarding their engagement and experiences in the

OPSG. Moreover, as is common in interview studies,

even though all the participants were offered the

opportunity to share feedback, it is possible the subset

who agreed to do interviews did not represent the full

breadth of participant OPSG experiences.

Nevertheless, this subset of participants was large

enough (9 out of 25 (36%) participants in both cohorts

combined) to provide a wide range of opinions and

experiences, which were sufficient to enable the

creation of rich themes (Braun & Clarke, 2021).

The qualitative focus provides depth to the study,

yet the absence of quantitative data might limit the

ability to generalize the findings. Nonetheless, in line

with established interview research practices, the goal

of this study was not generalizability (Crouch &

McKenzie, 2006), but rather generating conceptual

insights. The challenges faced by individuals are

worthy of future exploration. For example, future

research should explore technological barriers in

more details, e.g., ask process questions about initial

unfamiliarity with the GroupMe app and eventual

adoption or resistance with using the app. Questions

on participants’ technological change over the course

of the experiment can provide insight into how to help

participants with initial technological barriers

overcome these.

While our study primarily focused on the benefits

and challenges of OPSGs in breaking up prolonged

sitting, it's worth noting the potential overlap with

gamification strategies in promoting physical activity

goals and acknowledging the potential advantages of

incorporating gamification elements that could

provide an alternative means to motivate people in

workplace settings (Mazeas et al., 2022). It may be

beneficial to further investigate the advantages and

disadvantages of an OPSG approach compared to a

more gamified approach in the context of workplace

sedentary behavior interventions. Future research

could aim to explore the distinctions and possible

collaborations between these approaches, as well as

the effects on participant engagement, motivation,

and behavior change.

4.3 Recommendations

Findings from this research indicated several

challenges. To address them and pave the way for

more effective future research, we offer the following

recommendation ideas for further exploration.

Participants sometimes struggle to find the time

and cognitive resources for active engagement in

OPSG. For time demand, we can provide a system of

reminders and prompts and help participants to

implement time management strategies to allocate

time for OPSG interactions. For cognitive resource

demand, we can use a messaging platform with

different threads and channels that enable participants

to focus on specific topics or conversations, reducing

the cognitive load associated with scrolling through a

continuous stream of messages.

Low engagement from participants and their

buddies can lead to feelings of isolation within the

group. We can add gamification elements, such as

challenges and quizzes and include a group moderator

who can facilitate discussions and provide words of

encouragement and support.

Some participants prefer one-on-one

communication with their designated buddies,

sometimes driven by concerns about discussing their

progress with a large group of unfamiliar individuals.

We can accommodate the preference for personalized

communication by providing alternative channels for

one-on-one interactions with buddies and schedule

regular virtual meetings with group members to

transform faceless interactions into face-to-face

connections, fostering a stronger sense of connection

and providing participants with a better

understanding of who they are interacting with in the

group chat.

By addressing these challenges and implementing

the recommended solutions, OPSG interventions can

be enhanced to better meet individual needs and

foster more meaningful engagement, ultimately

increasing their effectiveness in supporting behavior

change.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We presented a qualitative study of two cohorts

within a randomized control parent trial of GroupMe-

based peer support groups, aiming to reduce

sedentary behavior in the workplace. We found that

participation in online peer support groups not only

fosters a sense of community and accountability and

serves as a platform for the exchange of knowledge

and the reinforcement of study materials, but it also

plays a role in reminding participants about the

intervention, encouraging consistent and sustained

engagement in healthy behaviors throughout the

workday. Despite challenges like intermittent

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

172

participation, personal preferences, and issues related

to unfamiliar technology use and participation in a

group with unknown people, participants remained

motivated and encouraged by the sense of

community, aiding in their health goals. Studies

should continue to learn from participant experiences

to help address challenges and refine OPSGs within

interventions, as it can provide daily, organic

behavioral support in health behavior interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The MOV’D project was funded in part by the award

K01 HL136702/HL/NHLBI NIH HHS/United States.

This study was conducted with the financial support

of the Science Foundation Ireland Centre for

Research Training in Digitally Enhanced Reality (d-

real) under Grant No. 18/CRT/6224 and the ADAPT

SFI Research Centre for AI-Driven Digital Content

Technology under Grant No. 13/RC/2106_P2. For the

purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC

BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted

Manuscript version arising from this submission.

REFERENCES

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to

saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful

concept for thematic analysis and sample-size

rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and

Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/

2159676X.2019.1704846

CDC. (2022, June 3). All About Adult BMI. Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/

healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html

Chase, C. C., Chin, D. B., Oppezzo, M. A., & Schwartz, D.

L. (2009). Teachable Agents and the Protégé Effect:

Increasing the Effort Towards Learning. Journal of

Science Education and Technology, 18(4), 334–352.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-009-9180-4

Crouch, M., & McKenzie, H. (2006). The logic of small

samples in interview-based qualitative research. Social

Science Information, 45(4), 483–499.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018406069584

Damen, I., Brombacher, H., Lallemand, C., Brankaert, R.,

Brombacher, A., van Wesemael, P., & Vos, S. (2020).

A Scoping Review of Digital Tools to Reduce

Sedentary Behavior or Increase Physical Activity in

Knowledge Workers. International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2),

Article 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020499

Delisle, V. C., Gumuchian, S. T., Rice, D. B., Levis, A. W.,

Kloda, L. A., Körner, A., & Thombs, B. D. (2017).

Perceived Benefits and Factors that Influence the

Ability to Establish and Maintain Patient Support

Groups in Rare Diseases: A Scoping Review. The

Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 10(3),

283–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0213-9

Dunstan, D. W., Dogra, S., Carter, S. E., & Owen, N.

(2021). Sit less and move more for cardiovascular

health: Emerging insights and opportunities. Nature

Reviews Cardiology, 18(9), Article 9.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-021-00547-y

Hargreaves, E. A., Hayr, K. T., Jenkins, M., Perry, T., &

Peddie, M. (2020). Interrupting Sedentary Time in the

Workplace Using Regular Short Activity Breaks.

Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine,

62(4), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000

000001832

Iliffe, L. L., & Thompson, A. R. (2019). Investigating the

beneficial experiences of online peer support for those

affected by alopecia: An interpretative

phenomenological analysis using online interviews.

The British Journal of Dermatology, 181(5), 992–998.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17998

Karusala, N., Seeh, D. O., Mugo, C., Guthrie, B., Moreno,

M. A., John-Stewart, G., Inwani, I., Anderson, R., &

Ronen, K. (2021). “That courage to encourage”:

Participation and Aspirations in Chat-based Peer

Support for Youth Living with HIV. Proceedings of the

2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.34453

13

Leelawong, K., Davis, J., Vye, N., Biswas, G., Schwartz,

D., Belynne, K., Katzlberger, T., & Bransford, J.

(2002). The effects of feedback in supporting learning

by teaching in a teachable agent environment. The Fifth

International Conference of the Learning Sciences,

245–252.

Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a Thematic

Analysis: A Practical, Step-by-Step Guide for Learning

and Teaching Scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher

Education, 9(3).

Mazeas, A., Duclos, M., Pereira, B., & Chalabaev, A.

(2022). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Gamification

on Physical Activity: Systematic Review and Meta-

analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of

Medical Internet Research, 24(1), e26779.

https://doi.org/10.2196/26779

Mead, S., & MacNeil, C. (2006). Peer Support: What

Makes It Unique? International Journal of Psychosocial

Rehabilitation, 10(2), 29–37.

Olsen, H. M., Brown, W. J., Kolbe-Alexander, T., &

Burton, N. W. (2018). A Brief Self-Directed

Intervention to Reduce Office Employees’ Sedentary

Behavior in a Flexible Workplace. Journal of

Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 60(10), 954–

959. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001389

Oppezzo, M., Tremmel, J. A., Kapphahn, K., Desai, M.,

Baiocchi, M., Sanders, M., & Prochaska, J. (2021).

Feasibility, preliminary efficacy, and accessibility of a

twitter-based social support group vs Fitbit only to

decrease sedentary behavior in women. Internet

Chatting for Change: Insights into and Directions for Using Online Peer Support Groups to Interrupt Prolonged Workplace Sitting

173

Interventions, 25, 100426. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.invent.2021.100426

Parry, S., & Straker, L. (2013). The contribution of office

work to sedentary behaviour associated risk. BMC

Public Health, 13(1), 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/

1471-2458-13-296

Pechmann, C., Delucchi, K., Lakon, C. M., & Prochaska, J.

J. (2017). Randomised controlled trial evaluation of

Tweet2Quit: A social network quit-smoking

intervention. Tobacco Control, 26(2), 188–194.

https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052768

Piedmont, R. L. (2014). Social Desirability Bias. In A. C.

Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and

Well-Being Research (pp. 6036–6037). Springer

Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-

5_2746

Radwan, A., Barnes, L., DeResh, R., Englund, C., &

Gribanoff, S. (2022). Effects of active microbreaks on

the physical and mental well-being of office workers: A

systematic review. Cogent Engineering, 9(1), 2026206.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2022.2026206

Sarkar, S., Taylor, W. C., Lai, D., Shegog, R., & Paxton, R.

J. (2016). Social support for physical activity:

Comparison of family, friends, and coworkers. Work,

55(4), 893–899. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-162459

Smythe, A., Jenkins, C., Bicknell, S., Bentham, P., &

Oyebode, J. (2022). A qualitative study exploring the

support needs of newly qualified nurses and their

experiences of an online peer support intervention.

Contemporary Nurse, 58(4), 343–354.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2022.2107036

Tremblay, M. S., Aubert, S., Barnes, J. D., Saunders, T. J.,

Carson, V., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., Chastin, S. F. M.,

Altenburg, T. M., Chinapaw, M. J. M., Altenburg, T.

M., Aminian, S., Arundell, L., Atkin, A. J., Aubert, S.,

Barnes, J., Barone Gibbs, B., Bassett-Gunter, R.,

Belanger, K., Biddle, S., … on behalf of SBRN

Terminology Consensus Project Participants. (2017).

Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN) –

Terminology Consensus Project process and outcome.

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and

Physical Activity, 14(1), 75. https://doi.org/10.1186/

s12966-017-0525-8

Wu, J., Fu, Y., Chen, D., Zhang, H., Xue, E., Shao, J., Tang,

L., Zhao, B., Lai, C., & Ye, Z. (2023). Sedentary

behavior patterns and the risk of non-communicable

diseases and all-cause mortality: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing

Studies, 146, 104563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnur

stu.2023.104563

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

174