Your Robot Might Be Inadvertently or Deliberately Spying on You:

A Critical Analysis of Privacy Practices in the Robotics Industry

Farida Eleshin

a

, Patrick Iradukunda, David Ishimwe Ruberamitwe and Eric Ishimwe

College of Engineering, Carnegie Mellon University, Kigali, Rwanda

Keywords:

Privacy, Externality, Robot, Consent, Choice.

Abstract:

In 2022, there were approximately 4.8 million operational robots, with 3.6 million of them serving industrial

purposes and another 1.2 million dedicated to various service applications (Statistics, 2022). Robots, irrespec-

tive of their intended function, act as a kind of ‘third eye’ in the realm of activities. As we witness the growing

capabilities of robotics, concerns about privacy implications in these domains are becoming increasingly com-

mon (Ryan, 2020). One notable aspect of these concerns is the profound impact of robots on surveillance.

Their ability to directly observe and record information magnifies their potential for data collection. This

paper delves into the externalities stemming from the use of data gathered by robots. It also investigates the

themes of consent and choice in the context of data acquisition by robotics. Moreover, we explore privacy

policies, protocols, and regulations applicable to robots and how robot companies comply with them. Surpris-

ingly, our research unveiled the fact that not all companies seek explicit consent from their users to collect their

personal information. This raises the unsettling possibility that your robot might be inadvertently or deliber-

ately spying on you. In some cases, companies even go as far as selling user data to third parties, including

data brokers.

1 INTRODUCTION

There are 4.8 million operational robots, with 3.6 mil-

lion robots used in industry and 1.2 million robots for

services in 2022 (Statistics, 2022). The International

Federation of Robotics, IFR, categorizes robots into

two based on their functionalities. Service and Indus-

trial Robots. According to them and based on the

International Organization for Standardization defi-

nition, the industrial robot is an “automatically con-

trolled, reprogrammable, multipurpose manipulator

programmable in three or more axes (Ifr, 2022a)” and

the service robot is one “that performs useful tasks for

humans or equipment excluding industrial automation

applications (Ifr, 2022b).”

These functionalities categorize the majority of

robots used in companies and homes based on sec-

tors and industries. Among the industrial robots are

Data Acquisition Robots, Mobile Robotic Systems,

and Manipulation robots (Robots.com, 2013). Ma-

nipulation robots perform functions such as weld-

ing material handling and material removing appli-

cations. Mobile Robotic Systems move items from

one place to another, and Data Acquisition robots

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-7053-3252

gather, process, and transmit information and signals

(Robots.com, 2013). Service robots comprise house-

hold robots such as cleaning robots like Roomba,

cooking robots, robotic lawnmowers, and robot pets

such as Aibo - a robotic puppy.

This increasing variety of robots has seen their use

in certain otherwise impossible sectors. For example,

robots have been widely adopted in the health sec-

tor in facilitating and assisting in minimally invasive

surgeries (H.-yin Yu and Hu, 2012). Nursing robots

autonomously monitor patients’ vitals, UV disinfec-

tion robots for sanitizing and disinfecting, robots for

emotional support, robots for diagnosing patient con-

ditions, etc(Banks, 2022).

Furthermore, at home, a robot is like the third eye

to activities regardless of its function. Households are

likely to own many more robots with varying func-

tionality to help with the owner’s behavior, reduc-

ing the burden of household chores and helping with

other daily activities (T. Denning and Kohno, 2009).

Law enforcement agencies rely on robotic technology

to monitor foreign and domestic populations (Ryan,

2020). Robots also provide private agencies with

tools for observation in security, voyeurism, and mar-

keting (Ryan, 2020). The number of robots used in

Eleshin, F., Iradukunda, P., Ruberamitwe, D. and Ishimwe, E.

Your Robot Might Be Inadvertently or Deliberately Spying on You: A Critical Analysis of Privacy Practices in the Robotics Industry.

DOI: 10.5220/0012422200003648

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2024), pages 219-225

ISBN: 978-989-758-683-5; ISSN: 2184-4356

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

219

industries is expected to skyrocket as they are used in

company automation processes (Mikolajczyk, 2022).

However, it is not uncommon to imagine the pri-

vacy implications of robots in these spaces (Ryan,

2020) because of the increasing power of robotics

observations. Robots facilitate direct surveillance,

which magnifies their ability to observe (Ryan, 2020).

They aid in the data acquisition of users’ health and

home information. They facilitate conversations with

their owners, gathering millions of useful and private

information. One may wonder what will happen if

hospital data acquisition robots are hacked. What

happens to the information of patients on them? Is

that data protected in any way? Do robot manufactur-

ing companies have access to that data, and what do

they do with them? Is there any consent sought from

robot users on the data acquired from them?

The sensory ability of robots raises certain con-

cerns about the information they record. It is still

vague whether robots record information more than is

necessary for functionality, record more information

than the owner has consented to, or record informa-

tion in locations where they have not been consented

(Kaminski, 2019). This raises the concern of robot

autonomy if these machines act independently and ac-

cess private information otherwise inaccessible.

In addition, robotics introduces many security and

privacy concerns to which people react differently.

Studies have proved that people are hardwired to re-

act differently to anthropomorphic technologies such

as robots (Lutz and Tam

`

o-Larrieux, 2021). It has also

been proved that adults behave differently near robots

and tend to enhance their privacy in the presence of

robots (K. Caine and Carter, 2012). On the contrary,

the rate of robot usage is increasing every day, mak-

ing us wonder if adults probe or notice the change in

their behaviors, as stated in some studies.

A further clarification indicates that the reason

behind such changing behavior is their inability to

accurately tell what information these robots col-

lect, who the data is transferred to, and how it is

processed (Postnikoff, 2022). This paper examines

the externalities of using data collected by robots.

It also studies consent and choice in data acquisi-

tion in robotics and research on some privacy mea-

sures/protocols/regulations for robots and how robot

companies comply with them.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

This section talks about how consent and choice are

taken in data acquisition in robotics and related stud-

ies done on it. It also talks about some externalities in

using data acquired by robots. It answers the ques-

tions of third-party usage of robotic data and con-

sumers explicitly giving their consent to companies

to take their information.

2.1 Consent and Choice in Robotics

Robots are programmed to sense, process, and record

the world around them.They have access to locations

and areas that humans cannot, and they can take in-

formation that humans may not be aware of (Ryan,

2020). With a robot’s ability to sense, record, and

speak in certain cases, it surveys every location it has

visited. This poses a threatening privacy invasion for

home robotics as robots access certain parts of the

home that humans may have never accessed, thereby

recording all the information of the house.

Robots might have first been allowed in homes as

toys. Kid toys with the ability to speak, and Pleo,

the robotic dinosaur, uses its speech recognition to

adapt to its owner’s behavior and do household chores

(Kaminski, 2019). With all these, one may wonder

what happens to all the data collected by these robots

used daily, both in our industries and at home. One

may also wonder if purchasing a robot automatically

gives consent to these robots and their companies to

record buyers’ data. It is still unclear whether grant-

ing an entity such as a robot access into your private

space automatically grants its permission to record in-

formation about that space (Kaminski, 2019).

The European Union’s General Data Protection

Regulation privacy (GDPR) and security law limits

firms and regulates how companies can collect, store,

use, share, and even access personal data. Compa-

nies protected by the GDPR seek consent from their

consumers and are limited to the use of personal data

from consumers (Wu, 2021). They are compelled

to notify their consumers of their usage by explicitly

stating it in their privacy policies and through pop no-

tifications on their mobile apps.

Companies that do not follow the GDPR seek con-

sent from their privacy policy. Therefore, privacy

policies must be clearly defined to include what in-

formation a robot can process and forward to their

company. Some companies make decisions on what

should be included in their privacy policies and how

to present them to their potential users and consumers.

They do so with robust legal language making it

hard for users to comprehend. Others present simple,

easily-comprehensible bullet points informing users

of the privacy protection level and data governance

policy offered. It may be reflected in a company’s

culture, the clarity and increased level of choice they

give to consumers over the control of their data and

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

220

its usage (Chatzimichali A, 2021). Such data protec-

tion and usage clarity could inform our choices when

purchasing home robots.

Research shows that robot companies use inter-

faces to disclose information about their data collec-

tion and processing mechanisms (Culnan and Mil-

berg, 1998). This put trust in the product, and

users were more willing to release private information

about themselves (Culnan and Milberg, 1998). Other

researchers also conclude that disclosing the informa-

tion handling practices of a company reduces privacy

concerns.

A study by Stedenberg et al. (Calo, 2020) shows

that data may be acquired from robot consumers with-

out their consent. In their study on an autistic child

whose parents purchased a robot to aid the child in

learning social cues at home, it was later discovered

that the robot stored videos and audio interaction of

the child and friends in a cloud server that the parents

could not access (Calo, 2020).

Another scenario is of a now 30-year-old disabil-

ity patient whose parents bought a learning robot to

help in learning and improve his speech but discon-

tinued using the robot after three years. The data and

records of the child persist with the robot manufac-

turer which has been acquired by a larger corpora-

tion. The data of this person has now been merged

with a larger dataset of others to be used by the com-

pany. In this case, the owners of the information were

not notified nor given a choice to allow these com-

panies to use their information, which is a breach of

their informational privacy and may cause subjective

harm [ (E. Sedenberg and Mulligan, 2016)] to them

because of the extended timescale in the use of their

data (Calo, 2020; E. Sedenberg and Mulligan, 2016).

2.2 Externality in the Use of Robotics

Data

In the case of the now 30-year-old who has persis-

tent data with a now-acquired robot manufacturer, the

externality is that the data is used building new pre-

dictive algorithms for the development of new robot

products, which was not the intended purpose of us-

ing the robot.

Calo claims that home robots present a novel op-

portunity for the government, private agencies, and

hackers to access information about private spaces in

people’s living spaces (Ryan, 2020). Their suscepti-

bility to attacks gives hackers access to data to be used

for other unintended purposes (Ryan, 2020).

Robot shopping assistants, used in Japan for me-

diating commercial transactions, collect consumer in-

formation and are later used in profiling. These robot

shopping assistants are meant to approach customers

and guide them toward a product. However, unlike

human clerks, they record and process every aspect

of the transaction, including capturing the images of

these consumers (Ryan, 2020), which are later pro-

cessed with face recognition for easy re-identification

and later used for market research.

Private institutions such as robot manufacturers,

government agencies, and third parties such as data

brokers pose a social threat by processing this in-

formation, leading to individual profiling (Lutz and

Tam

`

o-Larrieux, 2021) through data aggregation. An

example of this is in the case of an old woman who

purchased a robot to assist in her daily memory task

to slow down the progression of her memory loss dis-

ease. Because she is using the robot at home without

the supervision of her doctors, she is not protected by

the US federal government privacy laws, and her med-

ical information is subsequently sold to data brokers

(Calo, 2020).

One of the most controversial uses of AI data,

such as data from surveillance robots, is by the mili-

tary for performing missions such as reconnaissance

and assassinations (Ishii, 2017). The Office of the

Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology,

and Logistics published in a research paper in 2016

that robots act as autonomous weapons for selecting

and engaging targets which speed decision-making

and rapidly increase the autonomy of this transition

into warfighting capabilities in the advantage of the

US (of Defense, 2022).

Home robots, for example, Roomba, map every

detail in your house. It knows what furniture you

have and the size of all the rooms in your house. It

knows what you keep in each room measured by the

things it hits in your room. This data could help these

companies to deduce your income level, and you will

subsequently see ads for items you do not have or that

the robot thinks you need. This occurrence signifies

that data is shared with third parties. However, com-

panies claim that the information is shared with third

parties with users’ consent which is mostly sought

from privacy policies that most people do not even

read (Privacy-Not-Included, 2022).

3 METHODOLOGY

This paper analyzes the privacy policies of 20

US robotics companies to determine what data is

collected from users, how consent is taken from

users, the externalities in the data collected, and the

rules/regulations governing these companies in data

protection.

Your Robot Might Be Inadvertently or Deliberately Spying on You: A Critical Analysis of Privacy Practices in the Robotics Industry

221

The companies were selected on the basis of the

functionality of the robots they manufactured. For

example, general industrial robots, healthcare robots,

garbage sorting robots, vacuum cleaning robots, ther-

apeutic robots, etc. collectively classified under in-

dustrial or service robots. Of the 20 companies we

analyzed, 11 were industrial robot manufacturers and

8 were service robot manufacturers. Only one com-

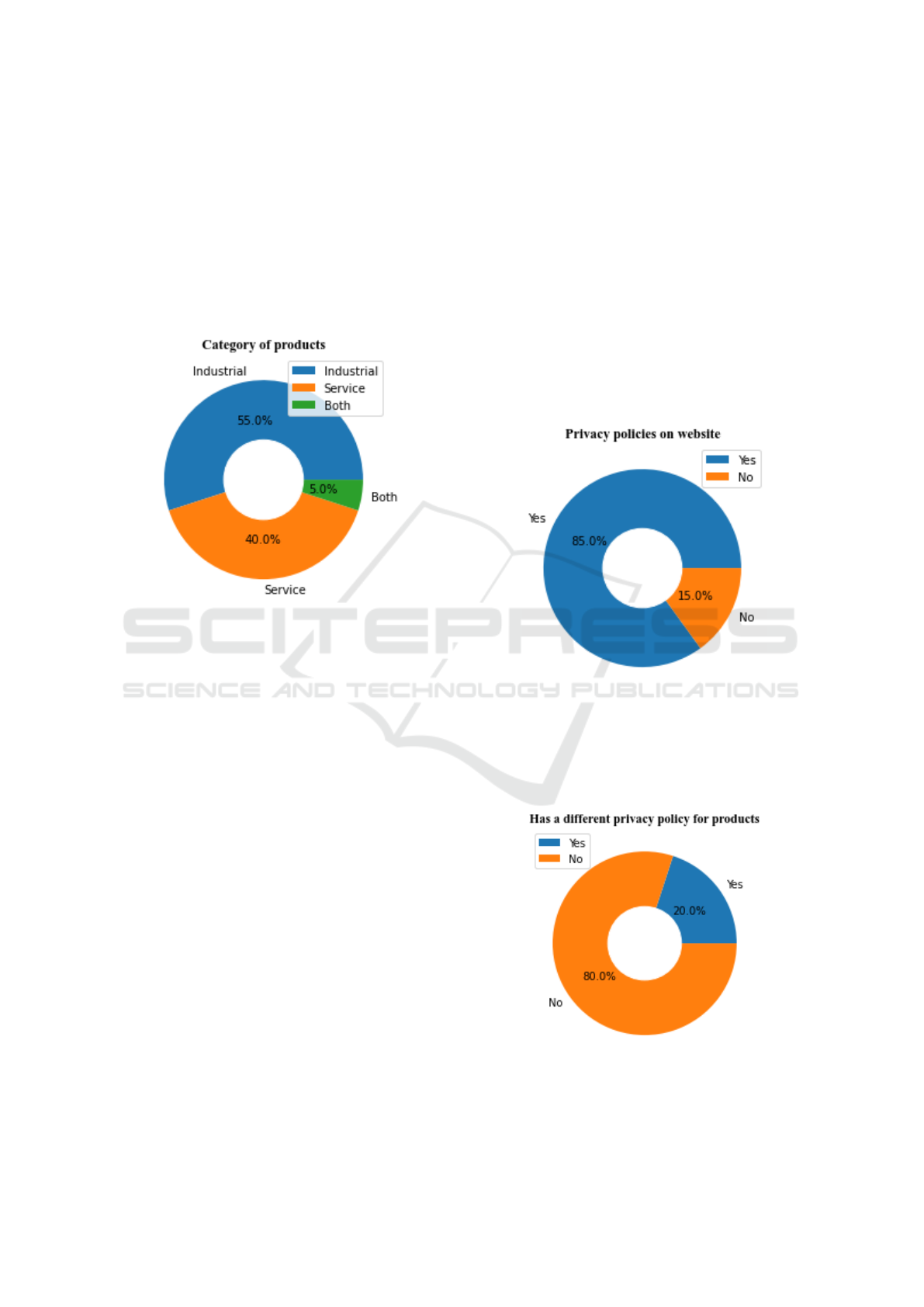

pany produced industrial and service robots, as seen

in the pie chart below.

Figure 1: Categorisation of companies.

For every company, we answered the following

questions to understand how the companies made

those decisions.

• Do they seek consent from users?

• Do they share information with third parties?

• If they do, how do they do it? Do they notify their

users in their privacy policies?

• What rules and regulations for data protection do

they use? For example, the EU GDPR, etc. Do

they explicitly state their compliance?

• What information do they collect? Location,

house size, etc.

• Is there anything odd you noticed we should add?

• Do they have different privacy policies for their

products?

These questions will help us understand what data

our friendly home robots and company robots collect,

whether it can be traced back to us, used against us,

used for re-identification, or used for purposes other

than intended, and to know if they sought our permis-

sion. The results will be presented on the basis of

their consent and notice to customers, sharing of data

to third parties, and their compliance with rules and

regulations surrounding data protection

4 RESULTS

This section examines the outcomes of the analysis

conducted on individual companies, focusing on their

practices regarding seeking consent for data collec-

tion, sharing data with third parties, and compliance

with rules and regulations.

Initially, it was observed that certain companies

lacked privacy policies on their websites, and insuffi-

cient information was available regarding their acqui-

sition. Consequently, the total number of companies

considered in terms of privacy policies was reduced to

17, as three companies did not provide access to their

privacy policies on their websites, as illustrated in the

accompanying pie chart.

Figure 2: Availability of privacy policies.

For companies that have privacy policies, 13 com-

panies do not have different privacy policies for each

of their products. However, 4 out of 17 compa-

nies have a specific privacy policy for their individual

robot products, as seen in Fig 3 below.

Figure 3: Companies with different privacy policies for

their products.

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

222

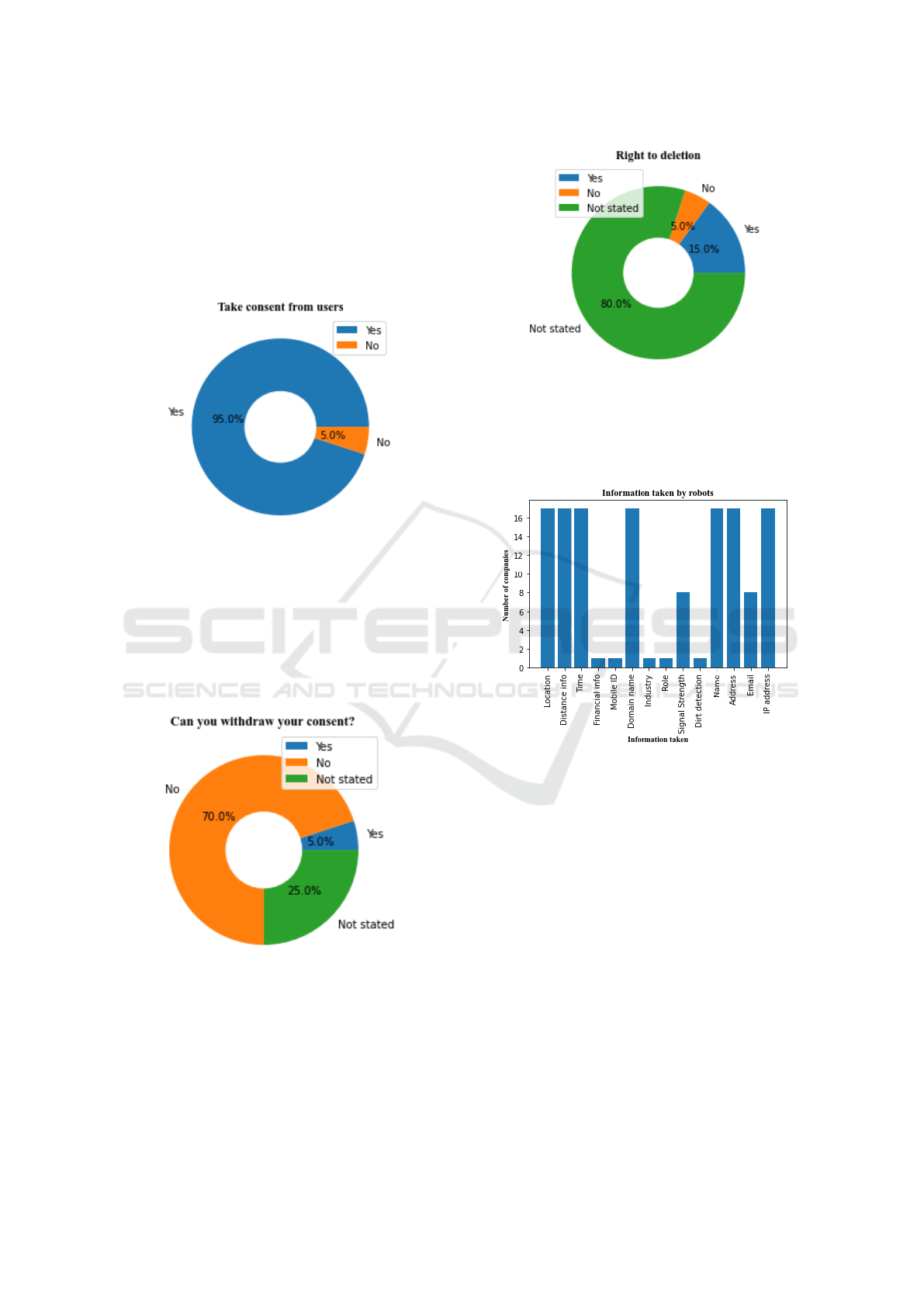

4.1 Consent in Data Collection

For most companies, you consent to their data collec-

tion policies by visiting their website or buying their

products. Some companies explicitly state them in

their privacy policies while others do not. As in Fig

4 below, it can be seen that 16 companies explicitly

take consent from users while one company does not.

Figure 4: Consent from users.

Some companies that explicitly take consent from

their users give them the right to withdraw their con-

sent and the right to delete their information acquired

by the company. 70% of these companies do not pro-

vide users the right to withdraw their consent, and

80% of these companies do not state in their privacy

policies that users can ask for the deletion of their in-

formation, as seen in the figures below.

Figure 5: Withdrawal of consent.

4.2 Third-Party Sharing of Data

Robot companies collect numerous data depending on

the functionality of the robots. From Fig 7 below, you

can see that most of the robotic companies take the

name, location, distance covered, address, and IP ad-

dress of the users of robots. On the other hand, only

Figure 6: Right to deletion.

a few companies take the signal strength for WiFis

and emails. Some companies further take the role of

users, their industry of work, and financial informa-

tion, as seen in Fig 7 below.

Figure 7: Information taken by robots.

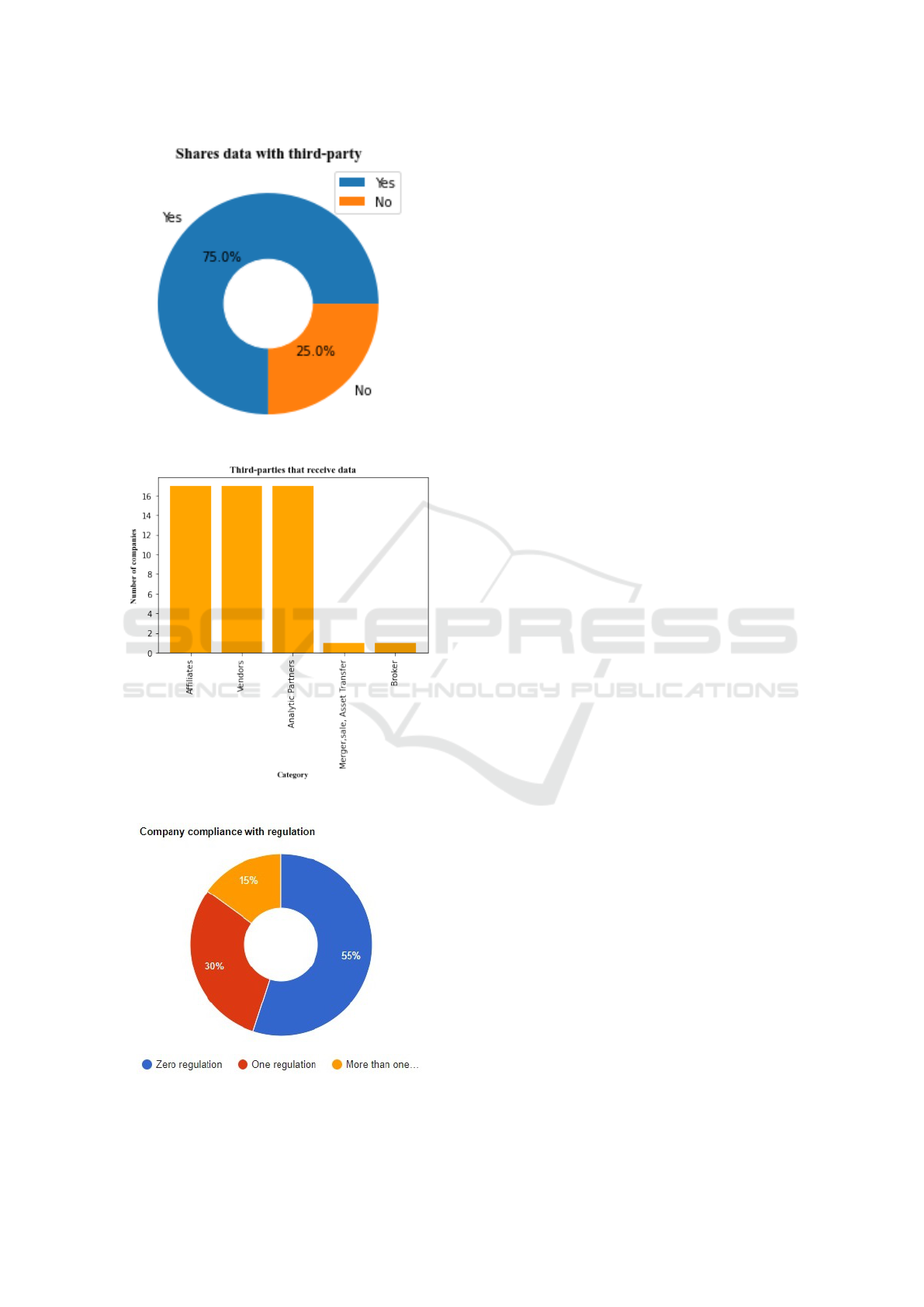

Third-party sharing of data is rampant in the

robotics industry as three-fourths (75%) of the com-

panies share data with third-parties, as seen below.

The subdivision of third parties these companies

share data with shows that almost all the companies

that share data with third-parties do so for analytic

purposes, share them with their affiliates, or brokers

as can be seen below.

4.3 Rules/ Regulations for AI Data

Protection

15% of these companies explicitly stated that they

comply with data protection regulations, including

COPA, CCPA, GDPR, and CoPPA. Surprisingly, 55%

of these companies do not state the data protection

laws they comply with, as seen below.

This analysis of robotic companies’ privacy poli-

Your Robot Might Be Inadvertently or Deliberately Spying on You: A Critical Analysis of Privacy Practices in the Robotics Industry

223

Figure 8: Companies that share data with third-party.

Figure 9: Categories of third-party data sharing purpose.

Figure 10: Company compliance with regulations.

cies shows that some companies don’t have privacy

policies, which raises questions concerning user un-

derstanding and openness. A few companies have

product-specific privacy policies, showing that they

recognize the need for tailored data protection strate-

gies.

While most companies explicitly seek consent for

data collection, the way users can withdraw consent

or delete their data varies, suggesting that users have

different levels of control over their information.

The common practice of disclosing user data to

other parties, mostly for analytical purposes, empha-

sizes how crucial it is to comprehend the particular

kinds of information that are shared. Robots gather

a wide range of data, from industry-specific informa-

tion to personal details, thus possible privacy issues

must be carefully considered.

Also, a significant number of companies do not

explicitly state the data protection regulations they

comply with, raising questions about the industry’s

adherence to legal frameworks. The fact that only a

few companies comply with specific regulations sug-

gests that standardized practices are needed to ensure

strong data protection across the robotics industry.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this analysis of the privacy practices of

robotic companies illuminates critical facets of data

protection within the industry. The absence of univer-

sally accessible privacy policies and the existence of

product-specific variations underscore the importance

of standardizing transparency practices to empower

users with informed choices.

The findings surrounding user consent reveal both

positive aspects, with the majority seeking explicit

consent, and areas for improvement, such as the lim-

ited provision for withdrawal and deletion. As tech-

nology advances, ensuring users have robust con-

trol over their data becomes increasingly paramount.

Users should be aware of the risks associated with us-

ing robotic products and services. They should care-

fully review the privacy policies of robotic compa-

nies before using their products or services, and they

should only share data that they are comfortable with

being shared.

The prevalence of third-party data sharing for ana-

lytical purposes demands a closer examination of the

categories of shared information. The extensive range

of data collected by robots, coupled with the observed

data-sharing practices, necessitates a balance between

innovation and safeguarding user privacy. Robotic

companies should take steps to be more transparent

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

224

about their data collection and sharing practices. They

should also take steps to better protect user data. This

may include developing privacy-enhancing technolo-

gies, such as differential privacy and federated learn-

ing.

Furthermore, the revelation that a considerable

percentage of companies do not explicitly cite the

data protection regulations they comply with raises

broader questions about industry-wide commitment

to legal frameworks. As regulatory landscapes evolve,

a collective effort is essential to align practices with

established standards, fostering a trustworthy and ac-

countable robotics ecosystem.

In moving forward, stakeholders, including com-

panies, policymakers, and users, must collaborate to

establish comprehensive and standardized guidelines.

These guidelines should prioritize transparency, user

consent, and adherence to data protection regulations,

ensuring the responsible and ethical evolution of the

robotics industry. Only through collective efforts can

we foster an environment where innovation harmo-

nizes with privacy, propelling the field toward a fu-

ture that prioritizes both technological advancement

and user trust.

REFERENCES

Banks, M. (2022). How robots are redefining health care: 6

recent innovations. RoboticsTomorrow.

Calo, M. R. (2020). 12 robots and privacy. Machine Ethics

and Robot Ethics.

Chatzimichali A, Harrison R, C. D. (2021). Toward privacy-

sensitive human–robot interaction: Privacy terms and

human–data interaction in the personal robot era. Pal-

adyn, Journal of Behavioral Robotics.

Culnan, M. J. and Milberg, S. (1998). The second ex-

change: Managing customer information in marketing

relationships. SRN Electronic Journal.

E. Sedenberg, J. C. and Mulligan, D. (2016). Design-

ing commercial therapeutic robots for privacy preserv-

ing systems and ethical research practices within the

home. International Journal of Social Robotics.

H.-yin Yu, D. F. Friedlander, S. P. and Hu, J. C. (2012).

The current status of robotic oncologic surgery. CA:

A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

Ifr (2022a). Industrial robots. IFR International Federation

of Robotics.

Ifr (2022b). Service robots. IFR International Federation

of Robotics.

Ishii, K. (2017). Comparative legal study on privacy and

personal data protection for robots equipped with arti-

ficial intelligence: Looking at functional and techno-

logical aspects. AI & SOCIETY.

K. Caine, S.

ˇ

S and Carter, M. (2012). The effect of monitor-

ing by cameras and robots on the privacy-enhancing

behaviors of older adults. 2012 7th ACM/IEEE In-

ternational Conference on Human-Robot Interaction

(HRI).

Kaminski, M. E. (2019). Robots in the home: What will we

have agreed to? Idaho Law Review.

Lutz, C. and Tam

`

o-Larrieux, A. (2021). Do privacy con-

cerns about social robots affect use intentions? evi-

dence from an experimental vignette study. Frontiers

in Robotics and AI.

Mikolajczyk, T. (2022). Manufacturing using robots.

of Defense, U.-D. (2022). https://www.defense.gov.

Postnikoff, B. (2022). When robots are everywhere, what

happens to the data they collect? Brookings.

Privacy-Not-Included (2022). irobot roombas.

Robots.com (2013). Three types of robotic systems. Robot-

Worx.

Ryan, R. (2020). Robots and privacy. Machine Ethics and

Robot Ethics, Routledge.

Statistics, R. I. (2022). Strategic market research.

T. Denning, C. Matuszek, K. K. J. S. and Kohno, T. (2009).

A spotlight on security and privacy risks with future

household robots. Proceedings of the 11th interna-

tional conference on Ubiquitous computing.

Wu, S. (2021). Communicating your ai and robotics

products’ gdpr compliance - artificial intelligence and

robotics law - silicon valley law group. Artificial In-

telligence and Robotics Law.

APPENDIX

Names of Companies we studied

• Sarcos

• AMP robotics

• Anduril

• Intuitive

• PickNik

• Oyster

• Boston Dynamics

• Outrider

• Vicarious

• Skydio

• Honeybee Robotics

• Tempo

• Diligent

• Piaggio

• Barrett Technology

• iRobot

• Nuro

• Tempo Automation

Your Robot Might Be Inadvertently or Deliberately Spying on You: A Critical Analysis of Privacy Practices in the Robotics Industry

225