Strategic Oversight Across Real-World Health Data Initiatives in a

Complex Health Data Space: A Call for Collective Responsibility

Lotte Geys

1,2,3 a

and Liesbet M. Peeters

1,2,3 b

1

University MS Center, Pelt-Hasselt, Belgium

2

Biomedical Research Institute (BIOMED), Hasselt University, Diepenbeek, Belgium

3

Data Science Institute (DSI), Hasselt University, Diepenbeek, Belgium

Keywords: Landscaping, European Health Data Space, Interoperability Challenges, Information Scattering.

Abstract: Reusing real-world health data is useful, but challenging. Multiple initiatives exist and more are continuously

arising to overcome these challenges, but the strategic oversight across these initiatives is lacking, which leads

to a fragmented ecosystem. An overview of which initiatives that work on unlocking real-world health data,

making this data accessible for research and/or innovation and/or policy and getting an idea about which

aspect of the ecosystem the initiatives are working on would be very helpful. It could help in figuring out how

initiatives can work in synergy in order that consortia can be formed more efficiently. We tried to create an

overview, resulting in a static list, but have thereby run into many problems and difficulties and have noticed

that the information is even more scattered than expected, and often ambiguous and unclear. This paper

highlights the need for strategic oversight in our complex health data space, defines key challenges and

focuses on solutions and strategies for overcoming these challenges, and aims to guide the future of health

data research and innovation on a global scale, offering a valuable resource for stakeholders in the field.

1 REUSING REAL-WORLD

HEALTH DATA IS USEFUL,

BUT CHALLENGING

1.1 Europe Acknowledges Great

Promise in the Reuse of Health

Data

The European Commission has been working for

several years on a strategy for data sharing. In this

context, in February 2022, the Data Act, which is a

proposed regulation that clarifies who is allowed to

create value from data and under which conditions,

was adopted by the European Commission (link to

Data Act: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/

policies/data-act). With a specific focus on the

healthcare domain, Europe has been making

continuous efforts aiming at enhancing the

harmonization and integration of health data, which

is needed in order to be able to create a digitized and

connected healthcare system, as foreseen in the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1919-9366

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6066-3899

European Health Data Space (EHDS) regulation (link

to EHDS regulation: https://health.ec.europa.eu/

publications/proposal-regulation-european-health-

data-space_en). The EHDS regulation aims at

unleashing the full potential of health data by

supporting the reuse of health data for better

healthcare delivery, better research, innovation and

policy making.

1.2 Several Socio-Technical Challenges

Are Obstructing Us from Scaling

Reusing Health Data

Several socio-technical challenges obstruct us from

reaching the true potential of reusing real-world

health data, such as the level of awareness and

understanding on the use and/or importance of real-

world health data differs between individuals,

different stakeholders have different needs, finding

and assessing health data sources is challenging and

time-consuming, limited interoperability and the

combined complexity of governance, ethical and

Geys, L. and Peeters, L.

Strategic Oversight Across Real-World Health Data Initiatives in a Complex Health Data Space: A Call for Collective Responsibility.

DOI: 10.5220/0012417700003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 2, pages 577-584

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

577

legal barriers, as well as technical challenges in data

management and analyses, impacts the execution of

large-scale initiatives. This section takes a closer

look at these problems and potential solutions.

1.2.1 Limited Awareness Leads to Limited

Engagement

The level of awareness and understanding of the use

and/or importance of real-world health data differs

between individuals, resulting in different levels of

engagement to contribute to the health data space. In

our experience, healthcare professionals or citizens

are often not motivated to consistently collect and

share health data in a structured way, and regulators

are reluctant to acknowledge evidence generated

through non-controlled observational studies. On

the other hand, individuals can be engaged but not

sufficiently educated or trained to make informed

decisions (e.g. a director of a hospital that is willing

to invest in an improved data management strategy,

but is struggling with so-called ‘analysis-paralysis’

because they have no clue where to start). Examples

of activities that can be done to overcome this

challenge include (i) Advocating the message

“Health data - why should you care?” and

showcasing the impact of reusing health data by

sharing success stories from collaborative projects,

presented in a way that resonates with a layman

audience; (ii) Develop and disseminate educational

resources (with different target audiences in mind);

(iii) Facilitate interactions and collaborations and

promote knowledge exchange by organizing

workshops, conferences and other networking

events. By raising awareness, educating, and

demonstrating the benefits of health data, we can

bridge the gap in understanding and encourage

broader engagement in the health data space.

1.2.2 Different Stakeholders Have Different

Needs, Which Makes Large

Collaborative Efforts Complex and

Time-Consuming

Relevant stakeholders include, e.g. citizens,

healthcare professionals, researchers (private and

public), data custodians, industry and regulators.

Meeting the varied needs of different stakeholders

often requires complex coordination efforts. This

complexity can slow down decision-making

processes and the execution of large collaborative

efforts. To mitigate this, fostering a better

understanding and empathy among the various

stakeholders is crucial. This can be achieved by (i)

promoting more conversations and interactions

between different stakeholder groups, facilitating a

deeper appreciation of their unique perspectives and

requirements; (ii) documenting and disseminating

the strategies used within successful multi-

stakeholder projects in order to create a valuable

knowledge repository that can be leveraged by

others facing similar challenges.

1.2.3 Low Adoption of FAIR Guiding

Principles

As stated by Wilkinson et al. (Wilkinson M.D.,

2016), FAIRness -in which FAIR means Findable,

Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable- is a

prerequisite for proper data management and data

stewardship. It is important that real-world health

data is FAIR in the long-term as well (Holub P.,

2018). Finding and assessing health data sources is

challenging and time-consuming. Metadata

catalogues can empower end-users to assess and

compare metadata associated with health data

sources. Some examples of metadata that are of

interest include information about the (i)

organizational set-up and governance model of the

data source; (ii) type of data collected (categorizing

data sources by type, such as electronic health

records, -omics data, or medical images, allows

users to quickly identify datasets relevant to their

research or analytical needs); (iii) number of unique

patient records; (iv) detailed information about the

specific variables or data elements collected; (v)

basic information related to data quality, such as

validity, completeness, accuracy, and any quality

control measures in place. Additionally, health data

sources are heterogeneous in size, maturity and

depth, reducing their potential of reusing it.

Heterogeneous data from various resources are

difficult to integrate, thereby limiting the

interoperability. One approach to tackle this issue

involves the formulation of guidelines that serve as

a framework for standardizing data sources and

harmonizing their structure. Additionally, the

development, implementation, and widespread

adoption of data standards or common data models

are pivotal steps to ensure that health data sources

are more readily accessible and also compatible,

resulting in enhanced potential for reuse and

interconnectivity.

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

578

1.2.4 The Combined Complexity of

Governance, Ethical and Legal

Barriers, as Well as Technical

Challenges in Health Data Handling

and Analyses, Impacts the Execution

of Large-Scale Initiatives

Some examples of potential solutions to overcome

this moving forward include: (i) Developing and

implementing advanced cutting-edge technologies

that enable secure and privacy-preserving analysis of

health data; (ii) Documenting and streamlining

governance procedures and encouraging sharing of

successful ethical and legal frameworks that have

proven effective in similar projects; (iii) Adjusting

ethical and legal frameworks in collaboration with

funding agencies, policymakers and researchers if

necessary.

2 STRATEGIC OVERSIGHT

ACROSS INITIATIVES IS

USEFUL, BUT CHALLENGING

TO ACHIEVE

Multiple 'health data initiatives’ (in short: initiatives)

exist -and more are continuously arising- to overcome

the challenges discussed in the previous section.

However, the strategic oversight across these

initiatives is lacking. In the context of this paper, the

term 'initiative' is used to encompass all plans,

projects, or studies dedicated to addressing one or

more of the socio-technical challenges listed. We

focus on initiatives that still exist today and are more

than ‘just an idea or concept note’.

2.1 Strategic Oversight Across

Initiatives Is of Utmost Importance

An overview of which initiatives that work on

unlocking real-world health data, making this data

accessible for research and/or innovation and/or

policy and getting an idea about which aspect of the

ecosystem the initiatives are working on would be

very useful, because of a variety of reasons, including

but not limited to:

(i) Guiding newcomers: One of the main reasons

for emphasizing strategic oversight across health data

initiatives is to offer a fast and comprehensive

overview of the complexity of our health data space.

This is especially invaluable for less experienced

stakeholders. Navigating this intricate landscape can

be daunting, and an overview could serve as a guiding

beacon, ensuring that those entering this complex

space find direction and fundamental understanding

rather than feeling lost.

(ii) Knowledge leveraging and preventing

redundancy: Currently, the immense challenges

posed within our health data ecosystem are often

tackled in isolated silos, leading to a redundant

‘reinventing the wheel’ paradigm. By promoting

knowledge transfer and best practices, such oversight

could ensure efficient utilization of resources.

Moreover, it could enable a collective learning

process, significantly reducing duplication of efforts.

(iii) Analysing an initiative network: A holistic

view of how initiatives interconnect and the common

challenges they face is essential. It promotes

collaboration, highlights areas where collective

solutions are needed, and fosters a sense of unity in

addressing health data challenges.

(iv) Identifying gaps: Strategic oversight can

pinpoint gaps and shortcomings in the current health

data landscape, enabling targeted efforts to fill these

voids and enhance the overall quality and coverage of

available data.

(v) Influencing policy: A comprehensive

overview facilitates the development of policy

preparatory documentation, which can influence

policy decisions and regulations that shape the health

data landscape.

(vi) Forming consortia efficiently: For efficient

consortium formation, it is essential to know which

initiatives already exist, their specific focuses, current

status, and levels of advancement. This knowledge

forms the foundation for strategic collaboration and

innovation in the health data ecosystem.

2.2 The Health Data Landscape Is

Inherently Complex. Hence,

Achieving Strategic Oversight Is

Challenging and Time-Consuming,

but at Least We Tried

We kick-started 2023 with the good intention to try to

come up with a strategic oversight of existing

initiatives using a comprehensive and multi-faceted

approach. It could help in figuring out how initiatives

can collaborate in a better way, how they can work in

synergy in order that consortia can be formed more

efficiently. Additionally, it could open the eyes of

regulators and the government, leading to policy

preparatory documentation and be able to influence

policy. A rigorous literature review and internet

scanning served as the initial screening process for

identifying existing initiatives. Between January

2023 and April 2023, several search strings in several

Strategic Oversight Across Real-World Health Data Initiatives in a Complex Health Data Space: A Call for Collective Responsibility

579

search engines were applied using different

keywords. The sources searched were PubMed,

Google Scholar, Medline NLM, Cochrane, Scopus

and Cordis. The keywords used in the literature

search were: real world data; real world data AND

infrastructure; data infrastructure; (real world) data

infrastructure AND Europe; real world data strategy;

real world data and inventory; FAIR data ecosystem;

Digitization AND health AND RWD; FAIR data

management; secondary reuse AND health data; data

science strategy; data-driven medicine; data sharing

infrastructures; Big data and health; real world data

initiative; real-world data AND health AND

initiative.

Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were

defined for the scoping review. To be considered for

this review, studies had to meet the following

inclusion criteria: English-language articles; the

articles had to be reviews, systematic reviews or

meta-analyses. Studies that were published more than

5 years ago were excluded.

Next to this literature research, a general Google

search was performed to find initiatives that work on

unlocking real-world health data, making real-world

health data accessible for research and/or innovation

and/or policy. Additionally, information and

documents we received during the past months and

years from our network were checked and evaluated

on eligibility. This review allowed us to form a

preliminary shortlist of initiatives while gaining a

broader understanding of the field’s landscape.

Subsequently, during the period of May to August

2023, 13 semi-structured interviews were conducted

with authorities in the field of data spaces, health data

management and analyses to better understand which

information they considered critical to be gathered

from various health data initiatives. In addition, we

solicited these experts' opinions regarding how such

an exercise could become sufficiently exhaustive to

be useful, and could be kept up-to-date with minimal

effort from all stakeholders involved. The semi-

structured interviews, supported with an interview

guide that was used in a flexible way, gave much

opportunity for the respondents to speak very openly.

All interviews were done by Lotte Geys, who had no

personal connection with the experts. Interviews took

between 45 minutes and 1 hour and were recorded

(Google Meet) and transcribed verbatim.

The interviews were set-up in Google Meet and

the experts were asked the following: (i) their

opinions on the idea of setting up a living library of

existing initiatives, (ii) which questions from end

users the living library should be able to answer, (iii)

which initiatives they know about, (iv) who we could

possibly talk to in order to better carry out our

research and achieve our goal. Personal data was

collected from participants and processed in

accordance with the General Data Protection

Regulation (GDPR). This research was conducted

and seen as a task carried out in the public interest.

This study received approval from the UHasselt

Social (“Sociaal-Maatschappelijke”) ethical

committee (SMEC) (REC/SMEC/2022-2023/33).

2.3 To Date, It Is Impossible to Achieve

This Strategic Oversight Because of

Various Reasons

While striving hard for several months to achieve our

set goal towards providing strategic oversight across

initiatives, in the end, we were left deeply frustrated

because of 3 main reasons.

First of all, the information we need about the

initiatives is, most of the time, not available in the

public domain. Table 1 presents an overview of the

information deemed essential by experts for assessing

the value, impact and strategic positioning of health

data initiatives. The aim of an initiative, the data they

focus on, the way they work, what they exactly do,

etc., is often only vaguely described or not to be found

at all.

Secondly, a lot of initiatives are interlinked or

change their name and scope over time without

properly documenting these changes. It’s often very

confusing how they are linked or not clear that a

certain initiative originates from another one. It turns

out to be impossible to know for each initiative how

they originated and what it stands for. Many

initiatives started from a grant that expired after a few

years, but the initiative itself turned out to be

successful. These initiatives then often survive but

choose to work under a new name, potentially with a

new legal entity. This becomes very complex for

people who are trying to understand the ecosystem

and trying to get an overview of what is going on. To

give a concrete example: the Population Health

Information Research Infrastructure (PHIRI)

initiative allows for better coordinated European

efforts across national and European stakeholders.

PHIRI aims to generate the best available evidence

for research on health and well-being of populations

as impacted by COVID-19 to underpin decision-

making. It was born from two former initiatives:

BRIDGE Health and the Joint Action on Health

Information (InfAct) projects, which both have a

whole history. On top of that, PHIRI launched a

“spin-off initiative”: its Health Information Portal,

which is a one-stop shop facilitating access to

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

580

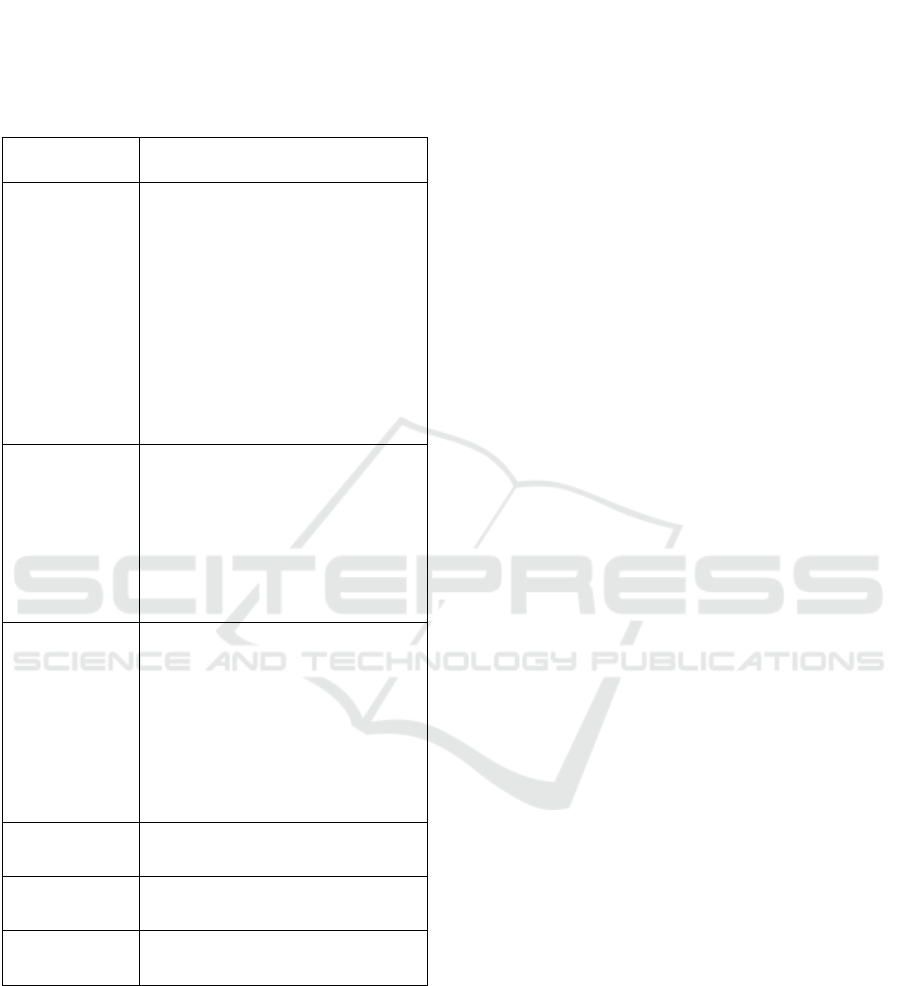

Table 1: Essential Information for evaluating Health Data

Initiatives. Through semi-structured interviews with

experts in the field, we inquired which information they

considered critical to be gathered from various health data

initiatives. This table presents an overview of the

information deemed essential by experts for assessing the

value, impact and strategic positioning of health data

initiatives.

Category

More specifically

Data Data type

Granularity

Centralized vs federated

Coding

Numbers

Data quality

Missing data

Link to prospective data

Standards

Category of health data

How to apply for data access

How to contribute

Stakeholders Which stakeholders are involved?

Who is it accessible to? Also for

industry? Also for commercial

purposes?

Looking for partners? How many

and type of partners?

Who is the initiator, who are

participating organizations?

Scope of the

initiative

Objectives

What are their strengths?

What specific socio-technical

challenges are they focusing on?

(E.g. standardization, infrastructure,

legal point of view, business

modeling)?

Geographical scope (E.g. Europe,

global vs specific region)

Costs/Financial

aspect

Free of charge or not

Funding

Governance of

the initiative

Links with other initiatives

General

information

Publications

Contact details

population health and healthcare data, information

and expertise in Europe. Unfortunately, PHIRI ended

in November 2023, and it could be that they will

continue to exist with another name, putting it at risk

of complicating it even more for people to

understand. This is just one initiative, but considering

that we found 67 initiatives

(10.5281/zenodo.10451144) and there are even more,

one might understand that it becomes impossible to

keep track of, especially when their websites are not

very detailed either.

And last, but not least, we were continuously

haunted by the question ‘where to start and where to

stop’. Initially, we wanted to include as many

initiatives as possible. But the more we progressed, the

more overwhelmed we were. The term “initiative” can

be interpreted in many different ways, making it

difficult to define precise inclusion/exclusion criteria.

3 OUR RESULTS AND

HIGHLIGHTED INITIATIVES

FROM OUR IMPERFECT

VENTURE

While we acknowledge that achieving a complete

overview is impossible (see reasons above in 2.3), we

believe the list of initiatives v2023

(10.5281/zenodo.10451144) serves as a valuable

starting point for those navigating the complex

landscape of health data initiatives. For each

initiative, details about the covered regions,

associated countries, website links, and whether the

initiative is specific to healthcare or encompasses

multiple domains are presented, as available. We

share it with the hope of assisting others in their quest

for clarity. Important Disclaimer: we acknowledge

that this list is neither exhaustive nor free from bias,

influenced by their geographical location and their

research emphasis on chronic disorders. However,

this list offers a starting point to address the issues

discussed in this position paper, aiming to provide

readers with insights gained after extensive online

exploration. The list resulting from our work can

assist individuals seeking clarity on the evolving

landscape of health data initiatives. While a

comprehensive overview remains elusive, this list

serves as a valuable resource to navigate the intricate

ecosystem. In this section, we will provide more

details on some highlighted initiatives to explain

some interesting emerging trends we have noticed

during our extensive landscaping exercise.

3.1 Initiatives Focused on Tackling

Data Heterogeneity - Data

Standards and Common Data

Models

As mentioned earlier, health data is heterogeneous in

size, maturity and depth, reducing their potential of

reusing it (limited interoperability). To reduce

Strategic Oversight Across Real-World Health Data Initiatives in a Complex Health Data Space: A Call for Collective Responsibility

581

heterogeneity, the health informatics community is

focusing on the development and adoption of data

standards (e.g. Logical Observation Identifiers

Names and Codes (LOINC), International

Classification of Diseases (ICD), and SNOMED

Clinical Terms (CT)) and common data models

(CDMs). Different initiatives are developing and/or

adopting different CDMs, potentially obstructing the

interconnection of these initiatives over time.

OMOP is an abbreviation of ‘Observational

Medical Outcomes Partnership’ and is a common data

model for observational healthcare data managed by

the Observational Health Data Sciences and

Informatics community (OHDSI: OHDSI.org). More

than 810 million unique patient records have been

mapped to the OMOP CDM, clearly showcasing the

wide adoption of this CDM. The OMOP CDM is

implemented within two important European large-

scale collaborative efforts: the European Health Data

and Evidence Network (EHDEN.eu) and the Data

Analysis and Real-world Interrogation Network in

the European Union (DARWIN.org). EHDEN,

established in 2018, aims to build a network and

infrastructure that uses harmonized health data to gain

real-world evidence. It currently compasses 187 data

partners from 29 different countries. DARWIN, a

federated data coordination network established by

the European Medicine Agency, aspires to deliver

real-world evidence from across Europe on diseases,

populations and the uses and performance of

medicines (pharmacovigilance studies).

3.2 Initiatives Focused on Education

and Awareness Raising

Data Saves Lives (datasaveslives.eu) is a multi-

stakeholder initiative with the aim of raising wider

patient and public awareness about the importance of

health data, improving understanding of how it is

used and establishing a trusted environment for multi-

stakeholder dialogue about responsible use and good

practices across Europe. It is led by European

Patients’ Forum (eu-patient.eu) and European

Institute for Innovation through Health Data (i-

HD.eu). Data Saves Lives aspires to share relevant

information and best practice examples about the use

of health data and generate easy-to-use materials

about the basic concept related to the data journey.

The portal of data.europe.eu, aiming to be the central

point of access to European open data, educates

citizens and organizations about the opportunities that

arise from the availability of open data with their

“Academy tab”. An inspiring new trend within

recently approved programmes within Horizon

Europe (HE) and Innovative Medicine and Health

Initiative (IHI/IMI) is to disseminate lessons learned

more broadly to the public (e.g. EHDEN Academy

(academy.ehden.eu) and other initiatives within the

Big Data For Better Outcomes roadmap (bd4bo.eu)).

3.3 Initiatives Focused on a Specific Set

of Data Types

Distinct categories of data require tailed technical

solutions for data management, storage and analyses.

InterRAI (interrai.org) is a partnership of researchers

and practitioners in more than 35 countries committed

to improving healthcare for people in long-term care

by tackling the challenges that arise with handling so-

called ‘resident assessment instruments’ (RAI). RAIs

are scientifically validated instruments enabling an

assessment of the degree of dependency and the care

needs of individuals. The Health Outcome

Observatory (H20; health-outcomes-observatory.eu)

aspires to create a standardized data governance and

infrastructure system across Europe with a specific

focus on patient-reported information. Within the

European Strategy Forum on Research

Infrastructures (ESFRI.eu) roadmap, two initiatives

are focusing on tackling two specific sets of data

types: ELIXIR (elixir-europe.org), focusing on -

omics data (e.g. genomics, proteomics) and

EBRAINS (ebrains.eu) with a specific focus on brain-

related data (e.g. neuroimaging data). Interestingly,

ESFRI is currently working on a landscape analysis

which will provide an overview of the European

transnational research infrastructure ecosystem. The

Landscape Analysis will include research

infrastructure services, technology, instrumentation

and data aspects, as well as societal and economic

impact; it covers national, European and global scales

and will be published online in December 2023.

3.4 Initiatives Focused on a Specific

Disease Area of Interest

While the existence of broader, disease-independent

initiatives is undoubtedly advantageous, the

importance of preserving disease-specific initiatives

cannot be overstated. These specialized initiatives are

indispensable because of their domain expertise and

knowledge needed to meet disease-specific

requirements. Additionally, these initiatives are

crucial to improve the disease-specific community

engagement, and communication and collaboration

between stakeholders involved. Some interesting

initiatives showcasing this are: the Multiple Sclerosis

Data Alliance (msdataalliance.com); PIONEER

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

582

focusing on prostate cancer (prostate-pioneer.eu), the

European Platform on Rare Disease Registration, the

Haematological Outcomes Network in Europe

(HONEUR, portal.honeur.org) and the European

Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation

(EBMT.org).

3.5 Initiatives Focused on Streamlining

Governance Principles

The project entitled ‘Towards European Health Data

Space’ (TEHDAS; tehdas.eu) plays a pivotal role in

addressing the challenge of streamlining governance

principles within and across member states in the

context of the EHDS regulation. TEHDAS helps EU

member states and the European Commission to

develop and promote concepts for the secondary use

of health data to benefit public health and health

research and innovation in Europe. At the level of the

member states, national data authorities have already

been installed to act as the single-point-of-entry

responsible for orchestrating the reuse of health data

in a specific country. Examples include the Finnish

Social and Health Data Permit Authority (findata.fi)

and the French Health Data Hub (health-data-hub.fr).

In October 2022, the HealthData@EU Pilot project

started (ehds2pilot.eu), bringing together 17 partners

including health data access bodies, health data

sharing infrastructures and European agencies. The

HealthData@EU Pilot project is a two-year-long

European project co-financed by the EU4Health

programme. It will build a pilot version of the EHDS

infrastructure for the secondary use of health data.

3.6 Initiatives not Focusing Specifically

on Health, but that Could Deliver

Interesting Insights to Be

Leveraged to the Health Domain

The socio-technical challenges that we face in the

health data space are similar in other domains.

Therefore, it is interesting to follow and align with

some initiatives that have a broader scope. Examples

funded by the European Commission include: the

Data Spaces Support Center (DSSC, dssc.eu), the

European Open Science Cloud (EOSC; eosc-

portal.eu) and Open Digitising European Industries

(opendei.eu). The DSSC explores the needs of data

space initiatives, defines common requirements and

establishes best practices to accelerate the formation

of sovereign data spaces as a crucial element of digital

transformation in all areas. One of the key objectives

of the DSSC is to establish a Network of Stakeholders

that aims to build a strong and innovative data

ecosystem in Europe through the development of

common data spaces in strategic economic sectors

and domains. OpenDEI focuses on “Platforms and

Pilots” to support the implementation of next-

generation digital platforms in four basic industrial

domains: manufacturing, agriculture, energy and

healthcare. The ambition of EOSC is to provide

European researchers, innovators, companies and

citizens with a federated and open multi-disciplinary

environment where they can publish, find and reuse

data, tools and services for research, innovation and

educational purposes. EOSC ultimately aims to

develop a Web of FAIR Data and services for science

in Europe upon which a wide range of value-added

services can be built. These range from visualization

and analytics to long-term information preservation

or the monitoring of the uptake of open science

practices.

There are some interesting arising initiatives that

focus mainly on some of the more technical

challenges requiring privacy-preserving

decentralized storage and analytics like federated

learning. Besides the already previously mentioned

health-specific initiatives ELIXIR, EHDEN, OHDSI

and EBRAINS, SOLID (solidproject.org) and GAIA-

X (gaia-x.eu) are more general initiatives worth

considering to learn more about in this area. Solid is

a technical specification that allows citizens to store

their data securely in decentralized, private data

stores called “pods”. Gaia-X strives towards

developing and implementing a federated system

linking many cloud service providers and users

together in a transparent environment that will drive

the European data economy. Within the Gaia-x

initiative, the International Data Spaces (IDS;

internationaldataspaces.org) initiative aims at cross-

sectoral data sovereignty and data interoperability.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND

CALL-TO-ACTIONS TO THE

ECOSYSTEM

Our health data landscape is a mess and that is a

problem. Strategic oversight across initiatives is

crucial, because it could provide valuable guidance to

newcomers, promote efficient resource utilization,

identify common challenges, help fill gaps, influence

policy making and facilitate and speed-up consortium

formation. Striving to accomplish this strategic

oversight has been a challenging journey that left us

deeply frustrated. Although we did not expect it to be

easy, we have noticed that the information is even

Strategic Oversight Across Real-World Health Data Initiatives in a Complex Health Data Space: A Call for Collective Responsibility

583

more scattered than expected and is often ambiguous

and unclear.

However, we are hopeful that together we can

overcome some of these challenges moving forward.

To accomplish this, we suggest concrete call-to-

actions for different actors:

• Specific for the actors involved in the set-up

and implementation of the European Health

Data Space: Install multiple teams (e.g. at least

one per country) that safeguards the strategic

oversight within a member state and make sure

that orchestration and knowledge leveraging

across member states is facilitated. Libraries

or scientific reports providing strategic

oversight are only useful when they are kept

up-to-date and the efforts required to

accomplish that should not be underestimated.

• Specific for funders of large-scale

collaborative efforts: Regularly scan the

landscape for existing initiatives and

encourage initiatives that request funding to

continue to work on top of previously

delivered results and successes (ideally

without pushing them to change their name).

Currently, innovation appears to be meaning

that you have to do something ‘new’, pushing

consortia to be ‘unique’ and again start from

scratch, leading to the ‘reinventing the wheel’

paradigm we see happening at the moment.

We believe that we can only truly scale-up

health data research if we start focusing on the

adoption and implementation of existing

solutions and principles instead of

continuously developing new solutions.

• Specific for the individuals leading these

initiatives: Make sure that at least your

websites are providing detailed information

about the what, (for) who, why and how of the

initiatives, as well as whether the initiative is

a still ongoing effort, whether or not acting

under a new name. In addition, be open to

understanding more about and learning from

other initiatives, even if they appear to be (at

first glance) in competition with your own

aspirations.

Together with the acquired experience resulting from

this landscaping exercise, we hope that the static list

we compiled (10.5281/zenodo.10451144) can

contribute to a start in creating policy preparation

documentation that will lead to clear guidelines on

how to proceed and work together in synergy and

move the data ecosystem in the right direction.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the experts who

generously contributed their insights and expertise

during the interviews. Their valuable input has been

instrumental in shaping our thoughts formulated in

this position paper. This work was supported by

Research Foundation - Flanders (FWO) for ELIXIR

Belgium (I000323N).

REFERENCES

Wilkinson M. D., Dumontier M., Aalbersberg I. J.,

Appleton G., Axton M., Baak A., et al. (2016). The

FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data

management and stewardship. In Scientific Data,

3:160018.

Holub P., Kohlmayer F., Prasser F., Mayrhofer M. T.,

Schlünder I., Martin G. M., et al. (2018). Enhancing

Reuse of Data and Biological Material in Medical

Research: From FAIR to FAIR-Health. In Biopreserv

Biobank., 16(2):97-105.

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

584