Transforming NCD Business Models in Switzerland: CSS Insurance

Perspective

Odile-Florence Giger

1a

, Christopher Bensch

2b

and Tobias Kowatsch

3,4 c

1

Institute of Technology Management, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

2

CSS Insurance, Lucerne, Switzerland

3

Institute for Implementation Science in Health Care, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

4

School of Medicine, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland, Centre for Digital Health Interventions,

Department of Management, Technology, and Economics, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Keywords: NCD Management, Business Model, Health Insurance, Telemonitoring.

Abstract: The worldwide incidence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is increasing, prompting exploration into

technological advancements that present fresh prospects for treating and managing NCDs. Numerous well-

established companies have been working in the field of NCD management, providing digital tools for the

efficient management. Although there are many digital health companies nowadays, building them up at scale

is difficult due to a heterogeneous, inefficient, and fragmented healthcare system. Therefore, we engaged in

a conversation with Christopher Bensch, healthcare expert at CSS – one of Swiss’ largest health insurers – to

understand better which business models may improve the management of NCDs. The insights are structured

along the business model framework of the “Magic Triangle”. We found that the integration of healthcare

providers is crucial when implementing the business model. Furthermore, new business models should be

launched lean, pragmatic, and improved along the innovation process within the given regulatory rules rather

than waiting for the regulatory environment to change.

1 INTRODUCTION

Approximately 2.2 million people in Switzerland

suffer from noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such

as heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary

diseases and diabetes (BAG, 2023). Total direct costs

of NCDs in Switzerland are estimated at 52 billion

Swiss francs per year, comprising about 80% of the

total healthcare costs (BAG, 2021). Hence, NCDs

stand as a widespread, detrimental, and expensive

condition.

Numerous companies offer their services for

managing NCDs (here referred as “NCD companies”)

leveraging digital health technologies (DHTs), i.e.

“computing platforms, connectivity, software, and

sensors [used] for health care and related uses.”

(Digital Therapeutics Alliance, 2023). These

technologies can improve access to health

information for both patients and providers, enable

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-7660-864X

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-5666-1914

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5939-4145

remote patient monitoring, and deliver timely

healthcare recommendations and reminders to

patients (Klonoff, 2013). Therefore, DHTs can

positively affect patients (Hood et al., 2016; Keller et

al., 2022) and care providers (Doyle-Delgado &

Chamberlain, 2020). Nevertheless, new DHTs at the

nexus of the healthcare and tech industry require a

successful business model (Steinberg et al., 2015).

But even if digital health business models are

successfully built, scaling them up is often

challenging due to heterogeneous, inefficient, and

fragmented healthcare systems (Garber & Skinner,

2008). This fragmentation can be seen also in

Switzerland, where each of the 26 cantons has a

distinct health legislation. Still, each canton is vital

in delivering healthcare services (Maurer et al.,

2022). It is said that one of the biggest barriers to new

digital business models in Switzerland is the lack of

regulatory transparency and reimbursement

846

Giger, O., Bensch, C. and Kowatsch, T.

Transforming NCD Business Models in Switzerland: CSS Insurance Perspective.

DOI: 10.5220/0012400100003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 2, pages 846-851

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

possibilities (Sojer et al., 2018). Facing many

challenges, the question arises of how new Swiss

business models for managing NCDs should look to

improve the treatment of patients and save costs

substantially.

Health insurance companies are interested in

finding innovative solutions to keep their plan

members healthy, improve the health outcomes for

those that need care at reasonable costs and thus

improving their competitive position in the market.

Therefore, we aimed to understand better how CSS,

one of Swiss’s largest health insurance companies,

thinks about offering services to individuals affected

by one or several NCDs. The CSS health insurance is

serving more than 1.75 Mio. customers, which make

up 20% of the total population (CSS, 2023). To tackle

healthcare challenges, CSS has implemented

different innovation strategies. First, they set an

example by founding the SwissHealth Ventures AG,

a fund of 50 million Swiss francs to invest in digital

healthcare startups (Enz, 2020). Together with

partners, CSS also launched the digital health

platform Well with the goal of improving integrated

care. They also initiated the CSS Health Lab, a

research collaboration with ETH Zurich and the

University of St. Gallen, with the overall goal of

researching digital business models, digital

biomarkers, and health interventions (CSS, 2023).

Against this background, we engaged in a

conversation with Christopher Bensch, who works in

strategy and corporate services as a healthcare expert

at CSS, to learn how he thinks about building up a

successful, sustainable, and scalable service for

individuals affected by NCDs. To this end, we asked

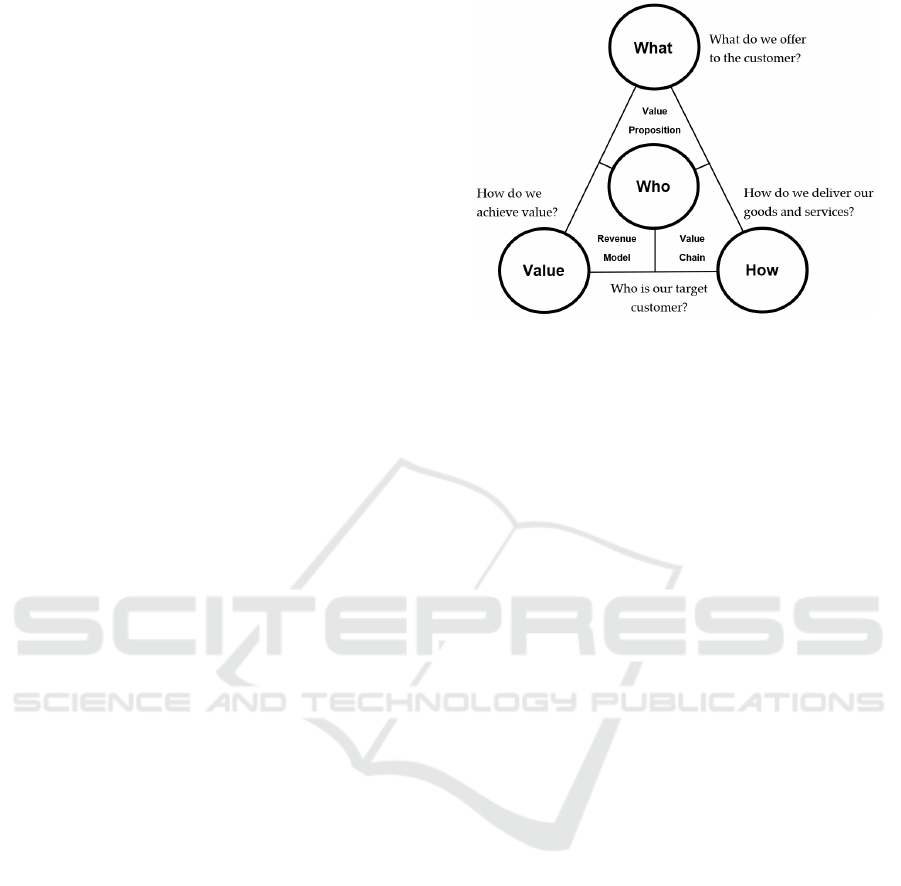

the following questions based on Gassmann et al.

(2017):

- WHAT should NCD companies offer (the

value proposition)?

- WHO should their target customers be (e.g.

companies, healthcare professionals,

patients)?

- HOW should their services be delivered (the

value chain)?

- How should these companies create VALUE

(the revenue model)?

In chapter 2, the insights of the interview with Mr.

Bensch will be structured along the business model

framework “Magic Triangle” as depicted in figure 1

(Gassmann et al., 2017). Furthermore, insights from

grey and academic literature will be used to discuss

the statements of Mr. Bensch. In chapter 3, we draw

a conclusion and show the limitations of this study.

Figure 1: Magic Triangle (Gassmann et al., 2017).

2 DISCUSSION

2.1 WHAT: Telemonitoring and

Integrated Software Solutions

According to Bensch (CB), telemonitoring solutions

are promising technologies to improve care

management for NCDs. Telemonitoring involves the

gathering, transmission, assessment, and

communication of a patient's personal health

information to their healthcare provider or extended

care team, all while being conducted beyond the

confines of a hospital or clinical setting, typically in

the patient's home. This is made possible through the

utilization of personal health technologies such as

wireless devices, wearable sensors, implanted health

monitors, smartphones, tablets, and mobile

applications (Gijsbers et al., 2022). There are many

conditions, such as diabetes, where regular

consultations are important but do not necessarily

require on-site and synchronous consultations (CB).

In Bensch’s opinion, the problem in NCD

management is that the time is not spent effectively

on those patients that need care most. This is due to

lacking means and time to identify the patients that

truly need care (CB). Generally, time is spread evenly

across all patients, so patients that manage their

disease well get more attention than needed, while

those that need more support are lacking the right

support (CB). Bensch sees here the true benefit of

telemonitoring (CB).

Telemonitoring has the potential to offer more

frequent and continuous patient monitoring. This

could enhance the quality of care, reduce the time

clinicians invest in patient management, and increase

monitoring frequency without overburdening

Transforming NCD Business Models in Switzerland: CSS Insurance Perspective

847

healthcare resources (Fazal et al., 2020; Ong et al.,

2016; Shah et al., 2021). This permits early

intervention and, ideally, the prevention of a

condition from worsening further which will then

lead to better health outcomes and ultimately save

costs (Malasinghe et al., 2019).

Furthermore, Bensch mentioned that there are

already digitized medical devices for patients (e.g.,

Continuous Glucose Monitoring) in NCD

management (CB). Those tools should be integrated

tightly in the health care pathways of providers to

enable telemonitoring and to improve the outcomes

of the treatment of the patient (CB). A recent study

supports these statements of Mr. Bensch, stating that

Switzerland could save up to 1.1 billion in costs only

by telemonitoring solutions for NCDs (McKinsey,

2021).

Furthermore, according to Bensch integrating

different software solutions in hospitals and general

practices could help improve the efficiency of current

care processes (CB). In Switzerland, many healthcare

providers are running on different IT systems, even in

the same clinic, different systems are not connected

leading to substantial process inefficiencies and

reduced operational agility (Blijleven et al., 2017).

Bensch names the example of Diabeter in the

Netherlands that has integrated a full technology

stack into their care pathways and into its daily

routine of care delivery. Diabeter, unlike traditional

hospital care, employs a specialized team for diabetes

patients. Each patient has a dedicated care manager

for continuous support, with regular check-ins and

annual assessments. The team provides ongoing care

adjustments through email, video calls, and phone

consultations. Patients also have access to a 24/7

emergency hotline for immediate specialist

assistance. Another example that Bensch mentioned,

is the US-based company Glooko that offers a tech

solution in diabetes management combining

telemonitoring and integration of different software

(CB). Glooko integrates several stakeholders

(patients, healthcare providers, medical device

companies, etc.) and different types of data (e.g.

blood glucose, diet, fitness, biometrics, insulin and

medication data) on one platform. It was shown that

their telemonitoring solution could significantly

improve an important health outcome (A1C, i.e., the

average blood sugar levels over the last three months)

of patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (Ranes,

2020).

2.2 WHO: Patients with Complex

Disease Management and

Healthcare Providers

According to Bensch, telemonitoring is especially

useful for patients with complex disease management

requirements and where connected medical devices

already exist (CB). Therefore, NCD business models

should target patients who suffer from severe health

conditions like diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or

respiratory diseases (CB). In the case of diabetes,

healthcare provider will then be able to monitor,

coach, diagnose and treat the patient based on current

and historical data (CB). This can lead to more

personalized and effective care and better decision-

making (Malasinghe et al., 2019; Stone et al., 2010;

Zhai et al., 2014).

Regarding software solutions, Bensch assumes

that it will be mainly the healthcare providers that will

be the paying target group (CB). Studies show, that

for them, it will be easier to streamline clinical and

administrative processes, collect needed outcome

data reducing the need for manual data entry and

paperwork, which will lead to reduced errors and

improve patient safety (Kaushal, 2002; Ruland, 2002;

Ventola, 2014). The lack of open APIs has made it

hard so far to seamlessly integrate the different

solutions and make those compatible with each other

(Faruk et al., 2022).

2.3 HOW: Importance of Healthcare

Providers

For telemonitoring and integrated software solutions,

healthcare providers should be involved early on, as

their IT systems need to be connected to other

solutions (CB). Studies show that almost half of the

Swiss healthcare providers mention that a major

barrier to not implementing DTHs is a lack of

interoperability with their patient information

systems (Sojer et al., 2018). Also, ineffective

stakeholder collaboration hinders DHTs to thrive.

Many core stakeholders lack incentives to pursue new

DHTs together (Landers et al., 2023). Furthermore,

according to Bensch, when developing a new

business model, businesses should not wait for the

regulations to change, as this is estimated to take

several years. Although a Swiss regulatory sandbox

exists (Experimentierartikel, KVG Art. 59b) where

cantons and tariff partners are allowed to implement

innovative pilot projects to curb cost growth and

promote digitization in healthcare, Bensch’s opinion

is clear: Even with this new article, the process of

building up new DHTs will take longer than five

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

848

years, as pilot projects have many requirements to

fulfill. Therefore, he recommends starting in a

pragmatic way within the given regulatory

framework and iterating the business model

continuously (CB).

2.4 VALUE: Patient Will Only Pay for

Integrated Solutions

Generating revenue is one of the most challenging

parts of NCD business models as many stakeholders

have different incentives (CB). In Bensch’s opinion,

patients will most likely only pay for DHTs (either

out of pocket or through additional insurance) if these

solutions are integrated in the care pathway of their

care provider (CB).

In other countries, DHTs are sometimes paid (or

provided by the state or health insurance. For

example, Germany established the Digitale

Versorgung Gesetz (DVG law) which makes DTx

solutions eligible for reimbursement (Mantovani et

al., 2023). Switzerland restricts what services a health

insurer reimburses, making it difficult for companies

to monetize their DHT offerings (CB). In some cases,

healthcare providers will pay for the DHT (e.g.

Glooko, eedoctors). Furthermore, as telemonitoring is

closely related to telemedicine, health insurance

companies may take over the reimbursement within

coverage of additional health insurance products

(CB). According to the doctor’s tariff “Tarmed”,

telemedicine can be reimbursed as well as the review

of patient records (CB).

3 CONCLUSIONS AND

LIMITATIONS

Implementing new business models in the NCD

management in Switzerland is still challenging.

Business models that might work in Switzerland

focus on diseases that are complex to manage and that

have digitized medical devices for the patients

(WHAT). Providing real value for both patients and

healthcare providers is crucial. As Switzerland is still

highly regulated and change can take several years, it

is advised to start lean, build up pragmatic solutions

within the current regulative setup, and improve the

business model iteratively (HOW). Lastly,

monetization still poses a major challenge. Potential

paying customers might be healthcare providers,

patients or insurances through additional coverage

(VALUE & WHO). Specifically, these findings

underline the importance of the integration of

healthcare providers when innovating in the field of

healthcare (HOW). Key success factors will be the

tight integration of technology components in

providers’ regular care pathways, overcoming the

interoperability issues between different IT systems

and handling the reluctance of healthcare providers

towards innovation, as many do not want to take an

active role in innovation (Landers et al., 2023).

Limitations

Although this work has emphasized the efficiency

benefits of telemonitoring, these benefits also need to

be harvested effectively. Telemonitoring solutions

generate a lot of data. Nevertheless, data without

interpretation will not necessarily lead to better

efficiency gains and improved outcomes. New

companies gathering many different data points

across thousands of individuals and making sense of

it generate powerful new business opportunities in the

future (Steinberg et al., 2015). One example is the

partnership between Glooko and Hedia, where

Hedia’s algorithm is integrated into the

telemonitoring solution of Glooko, making it easier

and faster for healthcare providers to interpret the

telemonitoring data of their patients (Glooko, 2023).

Therefore, in future work, a detailed analysis of how

telemonitoring solutions can provide substantial

value for healthcare providers is needed to guarantee

their willingness to pay.

Furthermore, this work is limited by its exclusive

dependence on a singular perspective of one expert

interview. Future research should integrate a more

diverse array of data sources, encompassing inputs

from various experts, studies, and industry reports.

This approach would offer a more thorough analysis,

ensuring the resilience and reliability of the findings.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

OFG and TK are affiliated with the Centre for Digital

Health Interventions, a joint initiative of the Institute

for Implementation Science in Health Care,

University of Zurich, the Department of

Management, Technology, and Economics at ETH

Zurich, and the Institute of Technology Management

and School of Medicine at the University of

St.Gallen. CDHI is funded in part by CSS, a Swiss

health insurer and MavieNext, an Austrian healthcare

provider, and MTIP, a Swiss investor company. TK

is also a co-founder of Pathmate Technologies, a

university spin-off company that creates and delivers

digital clinical pathways. However, neither Pathmate

Transforming NCD Business Models in Switzerland: CSS Insurance Perspective

849

Technologies, MTIP nor MavieNext was involved in

this research.

REFERENCES

Angerer, A., Hollenstein, E., & Russ, C. (2021). Der Digital

Health Report 21/22: Die Zukunft des Schweizer

Gesundheitswesens [96,application/pdf].

https://doi.org/10.21256/ZHAW-2408

BAG. (2021). National Strategy for the Prevention of Non-

communicable Diseases (NCD) strategy.

https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/strategie-und-

politik/nationale-gesundheitsstrategien/strategie-nicht-

uebertragbare-krankheiten.html

BAG. (2023). Zahlen und Fakten zu nichtübertragbaren

Krankheiten. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/

zahlen-und-statistiken/zahlen-fakten-nichtuebertragbar

e-krankheiten.html

Blijleven, V., Koelemeijer, K., & Jaspers, M. (2017).

Identifying and eliminating inefficiencies in

information system usage: A lean perspective.

International Journal of Medical Informatics, 107, 40–

47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.08.005

CSS. (2023). https://www.css.ch/de/ueber-css/story/unter

nehmen.html#:~:text=Die%20CSS%20Gruppe%20ver

sichert%20%C3%BCber,bei%20ihren%20Kundinnen

%20und%20Kunden.

Davis, J. W., Chung, R., & Juarez, D. T. (2011). Prevalence

of comorbid conditions with aging among patients with

diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Hawaii Medical

Journal, 70(10), 209–213.

Digital Therapeutics Alliance. (2023). What is a DTx?

https://dtxalliance.org/understanding-dtx/what-is-a-

dtx/

Doyle-Delgado, K., & Chamberlain, J. J. (2020). Use of

Diabetes-Related Applications and Digital Health

Tools by People With Diabetes and Their Health Care

Providers. Clinical Diabetes, 38(5), 449–461.

https://doi.org/10.2337/cd20-0046

Enz, W. (2020, September 29). Der Krankenversicherer

CSS setzt viel Geld auf Startups. NZZ.

https://www.nzz.ch/wirtschaft/der-krankenversicherer-

css-setzt-viel-geld-auf-startups-ld.1578925

Faruk, M. J. H., Patinga, A. J., Migiro, L., Shahriar, H., &

Sneha, S. (2022). Leveraging Healthcare API to

transform Interoperability: API Security and Privacy.

2022 IEEE 46th Annual Computers, Software, and

Applications Conference (COMPSAC), 444–445.

https://doi.org/10.1109/COMPSAC54236.2022.00082

Fazal, N., Webb, A., Bangoura, J., & El Nasharty, M.

(2020). Telehealth: Improving maternity services by

modern technology. BMJ Open Quality, 9(4), e000895.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000895

Garber, A. M., & Skinner, J. (2008). Is American Health

Care Uniquely Inefficient? Journal of Economic

Perspectives, 22(4), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1257/

jep.22.4.27

Gassmann, O., Frankenberger, K., & Csik, M. (2017).

Geschäftsmodelle entwickeln: 55 innovative Konzepte

mit dem St. Galler Business Model Navigator (2. Aufl.).

Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG.

https://doi.org/10.3139/9783446452848

Gijsbers, H., Feenstra, T. M., Eminovic, N., Van Dam, D.,

Nurmohamed, S. A., Van De Belt, T., & Schijven, M.

P. (2022). Enablers and barriers in upscaling

telemonitoring across geographic boundaries: A

scoping review. BMJ Open, 12(4), e057494.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057494

Glooko. (2023, April 11). Glooko Announces Partnership

with Insulin Dosing Algorithm Company Hedia. https://

glooko.com/news_reg/glooko-announces-partnership-

with-insulin-dosing-algorithm-company-hedia/

Hood, M., Wilson, R., Corsica, J., Bradley, L., Chirinos, D.,

& Vivo, A. (2016). What do we know about mobile

applications for diabetes self-management? A review of

reviews. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(6), 981–

994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9765-3

Kaushal, R. (2002). Information technology and medication

safety: What is the benefit? Quality and Safety in

Health Care, 11(3), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1136/

qhc.11.3.261

Keller, R., Hartmann, S., Teepe, G. W., Lohse, K.-M.,

Alattas, A., Tudor Car, L., Müller-Riemenschneider, F.,

Von Wangenheim, F., Mair, J. L., & Kowatsch, T.

(2022). Digital Behavior Change Interventions for the

Prevention and Management of Type 2 Diabetes:

Systematic Market Analysis. Journal of Medical

Internet Research, 24(1), e33348. https://doi.org/10.21

96/33348

Klonoff, D. C. (2013). The Current Status of mHealth for

Diabetes: Will it Be the Next Big Thing? Journal of

Diabetes Science and Technology, 7(3), 749–758.

https://doi.org/10.1177/193229681300700321

Landers, C., Vayena, E., Amann, J., & Blasimme, A.

(2023). Stuck in translation: Stakeholder perspectives

on impediments to responsible digital health. Frontiers

in Digital Health, 5, 1069410. https://doi.org/10.3389/

fdgth.2023.1069410

Malasinghe, L. P., Ramzan, N., & Dahal, K. (2019).

Remote patient monitoring: A comprehensive study.

Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized

Computing, 10(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s126

52-017-0598-x

Mantovani, A., Leopaldi, C., Nighswander, C. M., & Di

Bidino, R. (2023). Access and reimbursement pathways

for digital health solutions and in vitro diagnostic

devices: Current scenario and challenges. Frontiers in

Medical Technology, 5, 1101476. https://doi.org/

10.3389/fmedt.2023.1101476

Maurer, M., Wieser, S., Kohler, A., & Thommen, C.

(2022). Sustainability and Resilience in the Swiss

Health System. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/

WEF_PHSSR_Switzerland_EN.pdf

McKinsey. (2021, September). Digitalisierung im

Gesundheitswesen: Die 8,2-Mrd.-CHF-Chance für die

Schweiz. https://www.mckinsey.com/ch/~/media/mck

insey/locations/europe%20and%20middle%20east/swi

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

850

tzerland/our%20insights/digitization%20in%20healthc

are/digitalisierung%20im%20gesundheitswesen%20%

20die%2082mrdchance%20fr%20die%20schweiz%20

de.pdf

Ong, M. K., Romano, P. S., Edgington, S., Aronow, H. U.,

Auerbach, A. D., Black, J. T., De Marco, T., Escarce, J.

J., Evangelista, L. S., Hanna, B., Ganiats, T. G.,

Greenberg, B. H., Greenfield, S., Kaplan, S. H.,

Kimchi, A., Liu, H., Lombardo, D., Mangione, C. M.,

Sadeghi, B., … Better Effectiveness After Transition–

Heart Failure (BEAT-HF) Research Group. (2016).

Effectiveness of Remote Patient Monitoring After

Discharge of Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure:

The Better Effectiveness After Transition -- Heart

Failure (BEAT-HF) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA

Internal Medicine, 176(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/

10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7712

Ranes, L. (2020). Remote patient monitoring for adults with

type 2 diabetes. ADCES 2020 Research Abstracts. The

Diabetes Educator, 46(4), 398–406. https://doi.org/

10.1177/0145721720932682

Ruland, C. M. (2002). Handheld Technology to Improve

Patient Care: Evaluating a Support System for

Preference-based Care Planning at the Bedside. Journal

of the American Medical Informatics Association, 9(2),

192–201. https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M0891

Shah, S. S., Gvozdanovic, A., Knight, M., & Gagnon, J.

(2021). Mobile App–Based Remote Patient Monitoring

in Acute Medical Conditions: Prospective Feasibility

Study Exploring Digital Health Solutions on Clinical

Workload During the COVID Crisis. JMIR Formative

Research, 5(1), e23190. https://doi.org/10.2196/23190

Sojer, R., Röthlisberger, F., & Rayki, O. (2018). Angebot

und Nachfrage von digitalen Gesundheitsangeboten

(Teil I). Schweizerische Ärztezeitung. https://doi.org/

10.4414/saez.2018.17247

Steinberg, D., Horwitz, G., & Zohar, D. (2015). Building a

business model in digital medicine. Nature

Biotechnology, 33(9), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.103

8/nbt.3339

Stone, R. A., Rao, R. H., Sevick, M. A., Cheng, C., Hough,

L. J., Macpherson, D. S., Franko, C. M., Anglin, R. A.,

Obrosky, D. S., & DeRubertis, F. R. (2010). Active

Care Management Supported by Home Telemonitoring

in Veterans With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care,

33(3), 478–484. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1012

Ventola, C. L. (2014). Mobile devices and apps for health

care professionals: Uses and benefits. P & T: A Peer-

Reviewed Journal for Formulary Management, 39(5),

356–364.

Zhai, Y., Zhu, W., Cai, Y., Sun, D., & Zhao, J. (2014).

Clinical- and Cost-effectiveness of Telemedicine in

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and

Meta-analysis. Medicine, 93(28), e312. https://doi.org/

10.1097/MD.0000000000000312

Transforming NCD Business Models in Switzerland: CSS Insurance Perspective

851