Advocating for Harnessing the Power of Ecosystems in Healthcare:

The Case of an Ecosystem in the Realm of Parkinson's Disease - A

Position Paper

Dennis Vetterling

1a

, Philippe Lucarelli

2b

and Anja Y. Bischof

3c

1

Institute of Information Management, University of St. Gallen, Müller-Friedberg-Strasse 8, 9000 St. Gallen, Switzerland

2

Gerresheimer, Advanced Technologies, Solothurnerstrasse 235, 4600 Olten, Switzerland

3

School of Medicine, University of St. Gallen, St. Jakob-Strasse 21, 9000 St. Gallen, Switzerland

Keywords: Ecosystem, Values, Parkinson’s Diseases.

Abstract: In the contemporary healthcare landscape, organizations largely operate on their own, potentially limiting

comprehensive care for complex diseases. This position paper underscores the potential of utilizing the power

of an ecosystem as a structure for value creation within the realm of Parkinson`s disease. We analyze the

potential values that arise from utilizing an ecosystem for three entities, the organizations, the healthcare

system and the patients. In so doing, we propose a first set of benefits, i.e., values, that arise subdivided into

financial and non-financial values.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the healthcare sector, organizations such as pharma

companies, doctors, or medical equipment

manufacturers predominantly act independently to

provide products and services to patients. Especially

regarding diseases that demand complex care

offerings and where the potential benefits of

identification, cure, or management by combining

specific incremental services of different actors lie,

new ways of providing a joint service offering might

be promising.

Today's healthcare systems might be seen in a

status where a reboot is needed. Exemplarily, in the

healthcare system in Switzerland, the costs are rising

significantly, which is currently reflected in

increasing health insurance premiums (Bundesamt

für Gesundheit (BAG), 2023). The majority of the

direct costs of the healthcare system are attributable

to non-communicable diseases (NCDs), e.g., cardiac

diseases, musculoskeletal, and cancer (Bundesamt für

Gesundheit (BAG), 2022), making them a significant

lever.

a

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7278-8353

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6079-1623

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9318-5408

Looking at organizations in various sectors, it

becomes evident that they work jointly with other

organizations to provide complex service offerings to

their customers. A specific form of such a networked

environment for value creation is denoted as

ecosystem (Adner, 2017; Jacobides et al., 2018;

Moore, 1993; Vetterling & Baumöl, 2023a).

Ecosystems form a third organizational form for

value creation besides markets and hierarchies

(Jacobides et al., 2018). In ecosystems, the

organizations as actors provide their individual

capabilities in the form of increments for letting an as

complete service offering as possible arise for the

customers. Providing customer value is considered

the ecosystem's main goal (Moore, 1993). We

propose that in the case of ecosystems in the

healthcare sector, the provision of value by an as

complete service offering as possible for (potential)

patients is the north star for such settings which might

be beneficial for providing value for complex patient

journeys.

The realm of analyzing ecosystems, in general, is

dominated by large technology organizations such as

Apple, Google, or Amazon that harness the power of

many to let an overall complex service offering arise.

838

Vetterling, D., Lucarelli, P. and Bischof, A.

Advocating for Harnessing the Power of Ecosystems in Healthcare: The Case of an Ecosystem in the Realm of Parkinson’s Disease - A Position Paper.

DOI: 10.5220/0012399900003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 2, pages 838-845

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

Imagine, for example, the large number of

applications offered in the Apple app store provided

by millions of organizations. Building on the large

number of incremental building blocks, i.e.,

applications, based on one platform, i.e., iOS as

software, and the iPhone as a physical link, the

provision of a nearly completely individualizable

service for each user of an iPhone is possible.

Chances are high that not two iPhones show the exact

combinations of applications and, hence, the possible

combination of increments used shows a high degree

of possible individualization.

In this position paper, we now advocate for

harnessing the power of ecosystems, to create an as

complete service offering as possible in the realm of

one NCD, namely Parkinson’s disease (PD). We do

so by offering an overview of potential benefits for

different entities that could be seen as stakeholders of

such an ecosystem.

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative condition

that starts slowly and deteriorates with time (Alves et

al., 2005). Regrettably, there is currently no cure,

which means patients must manage it throughout their

lives for an extended duration. It causes various

constraints for patients, such as unintended and

uncontrollable movements, like tremors, muscle

rigidity, and difficulty in balance and coordination,

which highly impact patients' quality of life. Further,

among others, depression and anxiety, sleep

disturbance, and sudden freezes in movements are

possible effects.

In Switzerland, approximately 15,000 people are

affected by the disease (Parkinson Schweiz, n.d.). The

primary cause of PD is the gradual loss of dopamine-

producing neurons in the brain, particularly in an area

called the substantia nigra. Dopamine is a

neurotransmitter that is crucial in regulating

movement and mood. The exact cause of this

neuronal loss is still not fully understood, although

genetic and environmental factors are believed to

contribute (Pang et al., 2019).

Diagnosing PD is a complex process that demands

both the time and expertise of a plethora of experts

and organizations providing their services. Initial

symptoms may indicate other medical conditions,

necessitating extensive efforts, often involving a team

of specialists and time-consuming consultations. This

leads to significant expenses for the healthcare system

and a high degree of inconvenience for patients. Once

having identified the disease, various treatments are

available to help manage its symptoms, including

medication, physical therapy, or, in some cases, deep

brain stimulation surgery. These treatments aim to

improve the quality of life for individuals with PD by

addressing their motor and non-motor symptoms.

Unfortunately, today, these treatments are not offered

as a complete service to the patients but oftentimes in

a siloed way. Hence, exemplarily, the patient might

have to deal with various experts, different

appointments, and a broad field of fragmented

information provided to him.

PD is a progressive condition, and its

management often requires ongoing care and

adjustments to treatment plans as the disease

advances. Hence, this disease represents a complex

condition where the joint endeavors of many

organizations, each offering specific increments, i.e.,

modular aspects of an overall service, might benefit

the creation of an auspicious offering for the patients.

For establishing a new organizational setting,

such as an ecosystem, knowledge of the possible

benefits that might arise is necessary. Thus, we ask

the following question:

What are the benefits for organizations, healthcare

system, and patients that an ecosystem focusing on

Parkinson’s disease might offer?

To answer this question, we consider the

perspective of an ecosystem as a structure of

organizations that aim for a focal value proposition to

arise (Adner, 2017). We hereby consider the

ecosystem not only a passive construct surrounding

an organization but an actively shapable construct for

value creation. Further, we consider the perspective

of organizations, their raison d’être, and the

perspective of patients. In addition, we propose a

higher-level systems perspective to be considered. To

fuel our argumentation, we turn to analyzing the

approach of establishing an ecosystem within the

realm of PD by a global healthcare manufacturing

company.

2 BACKGROUND ON

ECOSYSTEMS

In general, two extrema exist for exchanging

information, creating value by the interaction of

different entities: markets and hierarchies. Both

structures arise, building on various organizations

that work together. A new structure of different

organizations as entities that create value that

arranges between these extremes is often seen in

practice. This new form is called an ecosystem and

positions itself as incorporating aspects of markets

and hierarchies, enabling the creation of a service

offering no single organization would be able to

Advocating for Harnessing the Power of Ecosystems in Healthcare: The Case of an Ecosystem in the Realm of Parkinson’s Disease - A

Position Paper

839

create on its own (cf. Adner, 2006; Autio & Thomas,

2022; Dattée et al., 2018; Jacobides et al., 2018;

Talmar et al., 2020). On the one hand, the actors

within the ecosystem obtain a certain degree of

autonomy since they are still offering their products,

i.e., increments, as parts of an overall service. These

increments stand in a complementary relationship to

one another, and hence, the actors, more precisely,

their increments, are not fully controllable by one

single entity (Jacobides et al., 2018). On the other

hand, a necessary condition of ecosystems is that all

actors within an ecosystem are aligned toward a

shared goal by an entity called the orchestrator

(Lingens et al., 2023), undermining the need for a

certain degree of leadership.

The main goal of an ecosystem as a value-creation

structure consisting of different organizations (cf.

Adner, 2017) is the creation of an as complete as

possible service offering for customers, i.e., patients

(Adner, 2006). For patients, a complex to create

solution can arise through the interplay of different

actors that no single actor could have offered alone.

Ecosystems as value-creation structures of

different organizations, or “organization[s] of

organizations” (Kretschmer et al., 2022, p. 407),

position themselves as parts of higher-level systems.

In our case, this higher-level system is the healthcare

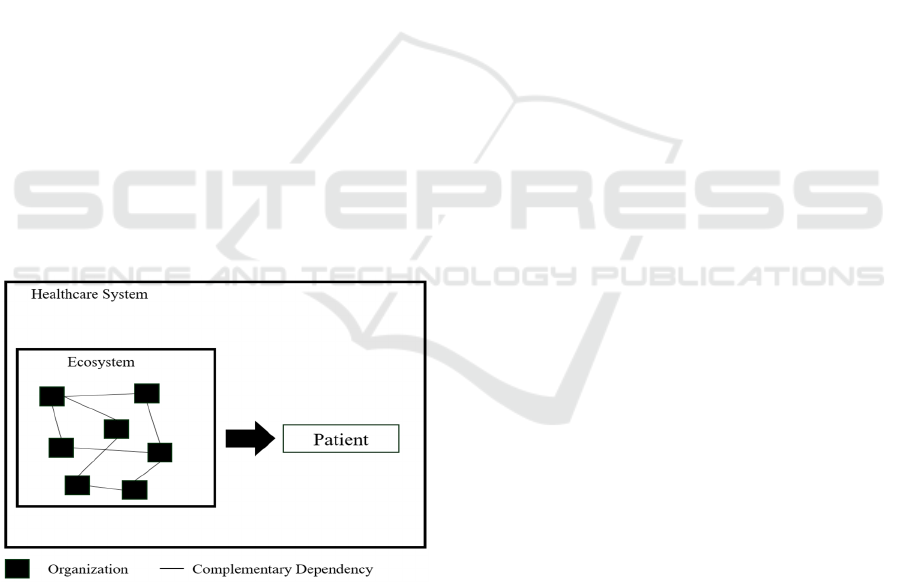

system. Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework

we propose for considering ecosystems as part of the

healthcare system.

Figure 1: Conceptual Representation of the Ecosystem as

Value Creation Construct in Healthcare.

Unfortunately, ecosystems are risky for

organizations to engage with since most such

endeavors fail (Pidun et al., 2020).One of the main

reasons seems to be the choice of the wrong

governance structure (Pidun et al., 2020). Another

risk could be seen in the need to open up as an

organization to work in the interconnection with other

organizations and competitors to exchange data and

partner relations, both basic resources within

ecosystems (Vetterling & Baumöl, 2023b).

In addition, a certain risk could be seen from a

higher, macro-level perspective. Since ecosystems

incorporate elements from markets and hierarchies

and position themselves just between both constructs,

it might be up to debate if, for society, such a new

construct offers more benefits than these other

extrema or might bring its risks. A first step towards

a possible evaluation might be identifying benefits

that might arise for entities affected.

Contrasting analyses in markets and hierarchies,

that as constructs have been affected by the notion of

value-based management, and hence consider a wider

spectrum of values, in ecosystems, the financial

perspective is still dominant (cf. Priem, 2007; Ritala

et al., 2013; Schreieck et al., 2021).

3 CONSIDERING VALUES IN

ECOSYSTEMS

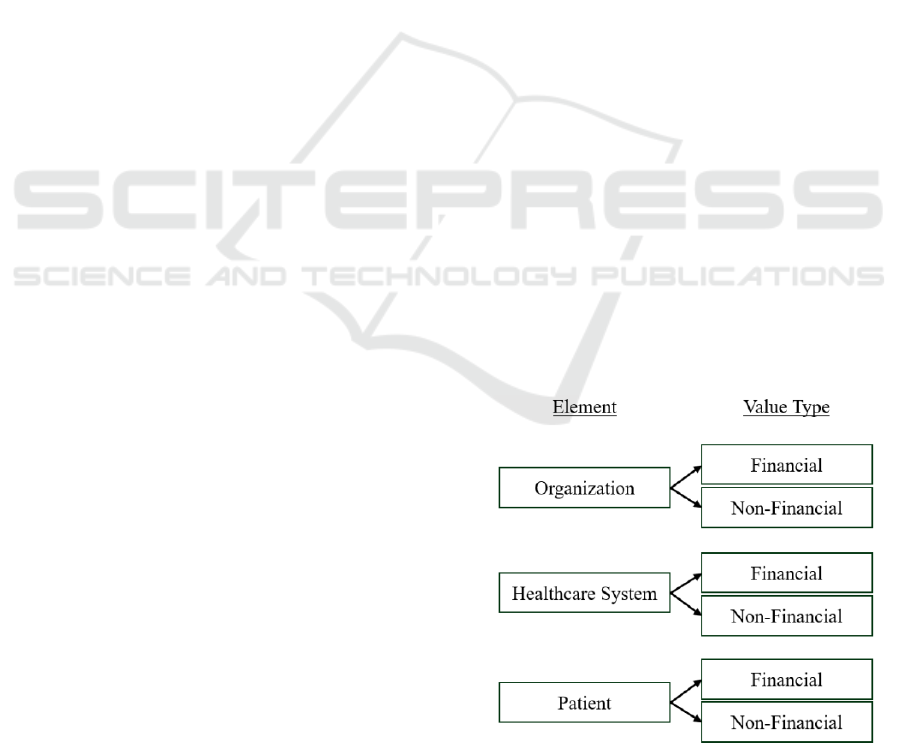

We propose three elements to be analyzed to gain a

picture of possible values to be obtained: actors, the

healthcare system, and patients.

First, actors, i.e., organizations, form the

essential ecosystem elements that jointly aim to let a

specific value proposition arise. Even though the

organizations might be more distinguished explicitly

by the capabilities they bring to the ecosystem, which

might ascribe them to particular roles, such as

orchestrator and partner, we here consider one class

of organizations as entities that bring increments to

the joint value creation setting. Organizations build

the focus of our analysis of benefits, i.e., values. This

is because we consider the ecosystem the structure for

value creation (Adner, 2017).

Second, we propose considering a higher-level

systems perspective, the healthcare system, for

analysis. The structure of a group of organizations

necessary for a value proposition to arise is supposed

to form the ecosystem (Adner, 2017). Hence, a

systems perspective is implicitly assumed already.

For analyzing the benefits of an ecosystem in the

healthcare sector, we propose considering a different,

higher-level perspective on the benefits of utilizing an

ecosystem to create value for a higher-level system—

the healthcare system.

Third, the perspective of the patients needs to be

considered. In our case, the patients in the realm of

PD might be seen to be the gravitation point of value

creation by the ecosystems` organizations aiming to

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

840

provide an as complete service offering as possible

for identification and care. Further, considering the

patients' perspective brings a certain time dimension

to our analysis. Dealing with PD as a specific disease,

we believe a patient's journey to be distinguishable in

pre- and post-identification of the disease. Early and

subtle symptoms start in the pre-identification period

and may be mistaken for another condition or as

typical signs of aging. Often, patients experience

frustration as they try to understand the cause of their

symptoms. To diagnose PD, various medical

evaluations such as physical examinations, blood

tests, neuroimaging, or sometimes genetic tests are

conducted. Once the diagnosis becomes more

apparent and symptoms progress, the patient is often

referred to a neurologist or movement specialist

specialized in diagnosing diseases like PD. In the

post-identification phase, the patient receives

treatment, and ongoing disease management is

required to maintain the health status and slow

disease progress. The treatment of the disease

includes the intake of medication, close monitoring of

symptoms evolving, and adjusting treatment plans

accordingly. Further, patients receive education about

the disease to increase health literacy and a person’s

capability of dealing with disease-specific challenges.

Early diagnosis and appropriate management are

crucial in helping maintain a higher quality of life.

4 ON VALUES IN ECOSYSTEMS

In general, financial and non-financial returns might

arise for actors when bringing their capabilities in for

value creation (cf. Chesbrough et al., 2018)—which

might also account for engaging in ecosystems. We

here postulate to further refine this perspective by

considering the following:

First, the basic elements of the raison d’être of

organizations should be considered to analyze the

possible benefits for organizations that engage in

ecosystems. Organizations generally follow the goal

of benefitting their stakeholders (Madden, 2020). To

do so, they must follow their basic determination and

create capital to sustain (Watson, 2021). Hence,

organizations benefit from all resources and

capabilities they can obtain by engaging in an

ecosystem that help them create capital. The

stakeholders benefit in the form of economic returns

in general. Hence, organizations should separate the

two types of possible benefits. On the one hand, direct

economic resources or capabilities, i.e., higher returns

or lower costs, are considered financial benefits—

these then can be utilized directly by the

organizations to benefit stakeholders since benefiting

stakeholders is oftentimes considered by increasing

the value of a company in financial terms, see

shareholder-value theory (cf. Ittner & Larcker, 2001;

Malmi & Ikäheimo, 2003; Rappaport, 1981, 1998).

On the other hand, indirectly benefiting resources or

capabilities enable better fulfillment of the

organization's raison d’être, such as gaining more

profound insights into the patients or enabling a

cultural change within the workforce.

Second, considering a system’s perspective,

anything that either lowers the costs of the existing

system or benefits by allowing for innovation might

be seen as beneficial. Benefits might arise from

providing the ecosystem`s output to the healthcare

system. These benefits might be denominated in

financial terms, e.g., increasing efficiency. But we

here aim to broaden the scope and further consider the

possibility of a more stable system or increasing the

potential of innovation, which might increase the

system's efficiency as additional aspects—such

aspects we propose to denominate as non-financial.

Third, for patients, benefits arise in either lower

overall system costs or a better treatment enabled by

a better-aligned service offering. A better treatment

might come in many different ways. Exemplarily, it

might be seen in an increased convenience during

necessary steps within the patient journey or by a

more complete treatment offering the potential for

better results. Hence, also for the patients, financial

values, e.g., lower costs, and non-financial, e.g., a

higher convenience or a more complete treatment,

might be observable.

Figure 2 refers to a representation of the elements

according to the value types to be analyzed.

Figure 2: Elements and Value Types.

Advocating for Harnessing the Power of Ecosystems in Healthcare: The Case of an Ecosystem in the Realm of Parkinson’s Disease - A

Position Paper

841

5 TURNING TO ONE SPECIFIC

ECOSYSTEM FOR

PROPOSING DIFFERENT

VALUES

A rather clustered market of different organizations

providing stand-alone solutions can be observed

within the healthcare sector in general. A “complete”

offering with different patient journey aspects is

hardly identifiable. The first attempts are shown in

endeavors like Well in Switzerland, where a

consortium of organizations set up a platform for

utilizing an ecosystem to bring healthcare closer to

the patients by combining the offers of various other

organizations, such as start-ups or health insurance

providers (Maicher et al., 2023; Well Gesundheit AG,

2023). Another example could be seen in the National

Health Service (NHS) in England, where entities of

different sectors, such as general practitioners, mental

health care, district nursing, and more, jointly build a

network of entities that benefit the patient (NHS

England, 2022). Nevertheless, we currently miss

focused attempts to create a more complete service

offering for patients by combining the increments of

different organizations for a combined service

offering in regard to highly relevant diseases such as

PD.

Consequently, we describe one imaginable

attempt led by a global healthcare manufacturing

company that aims to establish an ecosystem focusing

on identification and cure, i.e., offering support to

manage a life with PD. For that, it aims to connect the

potential of several digital technologies and physical

ports developed by third-party companies, i.e., start-

ups, other organizations, or itself.

The imaginable PD ecosystem operates as a

collaborative network dedicated to enhancing the

management of PD. In doing so, it plays a pivotal role

in improving the overall quality of care for

individuals affected by PD. The stakeholders within

this ecosystem encompass healthcare providers,

researchers, pharmaceutical companies, patient

advocacy groups, and patients themselves.

The primary objective of the PD ecosystem is to

facilitate holistic care, support, and research focused

on PD. It aims to provide comprehensive solutions

that address the diverse needs of patients and their

families, from the early stages of symptom

recognition to the post-identification phases.

For Pre-Identification: The ecosystem offers

educational resources, awareness campaigns, and

early symptom detection tools to empower

individuals and healthcare professionals in

recognizing the early signs of PD. This phase

emphasizes early intervention and timely diagnosis

that is enabled by combining the increments of a

group of actors that each are specialized in their

fields. Exemplarily, educational material could be

provided by organizations that already deal with the

topic of improving the health literacy of patients for

NCDs. Further new attempts to identify the disease

already in the early stages by applying technology,

such as tracking the movement with personal-health-

trackers could be a perceivable solution.

For Post-Identification: The ecosystem provides

access to a range of specialized care services,

treatment options, support networks, and ongoing

research initiatives. These components are designed

to improve the quality of life for those living with PD

and advance the understanding and management of

the disease. Here, exemplarily options to

conveniently track the development of the disease

with technology such as movement trackers or

measuring the brain activity for precisely adjusting

the medication doses are one option to be mentioned.

Further, related to more psychological factors,

establishing patient forums or standardized checklists

for special situations could be possible increments

contributing to the overall service.

In both phases, pre- and post-identification, the

benefit of the ecosystem offering an as complete as

possible service offering for patients is built by the

contribution of autonomous actors contributing to the

overall service offering and not by one single

organization. By that, more aspects of the patient

journey are coverable without needing one

organization to build up specialized capabilities.

Hence, the creation of a service offering that no single

actor alone would be able to create is possible (Adner,

2017).

Following this overview of the ecosystem

proposed, the following section will provide an

overview of the benefits of establishing such a new

ecosystem. The analysis will be guided by the three

elements for analysis: organizations, the healthcare

system, and patients. Further, a time dimension,

shown in pre- and post-identification of PD will be

considered.

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

842

6 ANALYSIS OF THE BENEFITS

OF BUILDING AN

ECOSYSTEM FOR MANAGING

PARKINSON`S DISEASE

Benefits for organizations might be seen in anything

that supports them to create capital, enabling the

organization to fulfill its raison d’être of benefiting its

stakeholders. For the healthcare system, we see

possible gains in light of efficiency and exemplarily

enabling innovation. For patients, financial and non-

financial benefits are to be imagined as well.

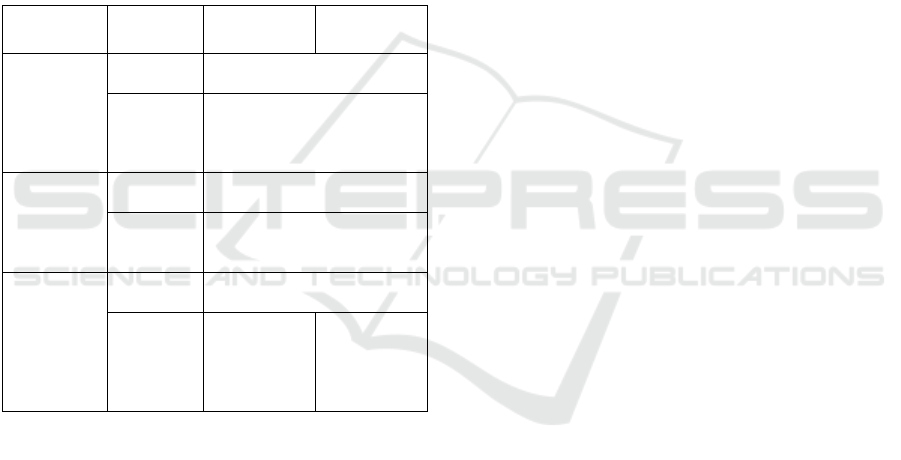

Analyzing the ecosystem mentioned above, we

propose the following non-exhaustive benefits to be

considered as values, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: List of exemplary Values for Entities.

Entity

Value

Class

Pre-

Identification

Post-

Identification

Organization

Financial

Higher revenue

…

Non-

Financial

Data Value Creation

Increasing Relevance

More Stable Network

…

Healthcare

System

Financial

Lower Costs

…

Non-

Financial

More stable system

Innovation

…

Patient

Financial

Lower Costs

…

Non-

Financial

More

Convenience

Earlier

Identification

…

More

Convenience

Better

Manageability

…

Organization: For the organization itself, we see

potential benefits that span both phases, the pre-and

post-identification. Potential benefits that might help

the organization create capital and, thus, fulfill its

raison d’être, are of a financial and non-financial

nature. As financial aspects creating a higher revenue

by providing increments within the ecosystem to

audiences that were not reached before entering the

ecosystem and being part of a service offering that

spans a longer customer journey is to be mentioned.

Non-financial aspects that help the organization

create classes of capital ultimately leading to

economic benefits for the stakeholders are manifold.

First, for the healthcare manufacturer or other

organizations engaging in the ecosystem, we see the

possibility of either gaining new data points,

increasing the data quality, or finding new ways of

excavating data for better knowing the patients

utilizing not their own but the capabilities of other

organizations within the network. Second, we see the

possibility of increasing the relevance of each

organization by either increasing the brand value or

creating innovative increments that benefit the overall

ecosystem. A third aspect we want to mention here is

the possibility of amplifying partner relationships,

which are already a basic resource for ecosystems,

whether with customers or other organizations. This

might be beneficial in creating more stability or even

accelerating the creation of new increments.

Healthcare System: The overall healthcare system

benefits from lower costs, enabled by a better service

offering. Exemplarily, applying technology provided

by start-ups for diagnosis might lower the need for

involving several experts in detecting the disease.

Further, building a data pool might enable the

discovery of patterns and hence benefit the right

identification of PD.

Further, we see non-financial benefits built by

higher stability of the overall system that the

complementary interrelation of the increments would

create. This would benefit the healthcare system since

higher stability would decrease the risk for necessary

adjustments when, e.g., organizations or procedures

change. In addition, the combination of organizations

might amplify innovative endeavors, e.g., by

combining research institutions with practitioners and

patients, benefiting the chances of innovation.

Patient: For the patients, we see the possible

financial benefit instantiated in lower costs. These

costs might be direct costs that could be lowered by

efficiency gains created within the ecosystem.

Furthermore, costs for searching for practitioners or

time spent identifying management could be lowered.

This is enabled by the service offering of the

ecosystem that not only increases convenience but

also lowers costs. In the direction of non-financial

benefits, we further see the benefit of an earlier

identification in the pre-identification phase that

might be enabled by the combination of increments

provided within the ecosystem. In the post-

identification phase, the combination of increments

might allow for better manageability of the disease.

Lastly, connecting the organizations within the

ecosystem might lead to benefitting innovation, and

hence, the potential for emerging new solutions that

benefit the patients, increasing their quality of life, or

even finding a solution for a cure might be amplified.

Advocating for Harnessing the Power of Ecosystems in Healthcare: The Case of an Ecosystem in the Realm of Parkinson’s Disease - A

Position Paper

843

7 CONCLUSION

We aimed at positioning the construct of ecosystems

within the healthcare sector. More specifically, we

aimed to propose a first set of different benefits such

a construct might offer in PD. We understand that the

list here might not be exhaustive, but it is a first

exemplary approach. Nevertheless, we are convinced

about the

benefits ecosystems might offer the

healthcare sector, as exemplified by our suggested

analysis of

one imaginable ecosystem focusing on

identifying PD and enriching the treatment path by

providing one joint solution.

Since ecosystems force organizations to transform

and might be considered a risky endeavor as most of

them fail (Pidun et al., 2020), knowledge about the

possible benefits to be achieved is an important pillar

to allow for informed decisions when considering a

respective transformation. Future research should

deepen the understanding of the possible benefits and

further provide insights into the respective

accumulation. Our list of exemplary benefits already

allows for seeing ecosystems' potential—for the

organizations, the healthcare system, and the patients.

Hopefully, we were able to plant the first seed for

growing an ecosystem regarding PD with our position

paper. Future research needs to validate our thoughts

provided here further. Research on values for

organizations in other ecosystems that already

function in providing a joint service offering might

form a good basis to be transferred and adjusted for

the healthcare sector.

Further, following development paths of

ecosystems represented in life-cycle models as

proposed, e.g., by Moore (1993), development

frameworks as proposed, e.g., by Nerbel and Kreutzer

(2023)), or stage-models exemplarily presented by an

early-, growth-, and late-stage, would benefit the

analysis.

Initially, we highlight the challenges regarding

PD connected to identification and management.

Establishing ecosystems by utilizing the power to

connect different organizations for one combined

offering offers the potential to help—patients and the

healthcare system. In addition, it offers financial and

non-financial benefits for each organization engaged.

Opening up for collaboration by each

organization to create the highest benefit for the

patients is what is necessary to establish ecosystems.

Hence, we call for organizations to focus on the

patient and elaborate on new ways of a joint value

proposition.

Limitations: This position paper is subject to some

limitations. First, it is a conceptual paper; hence, the

developed ideas need to be proven for feasibility and

practicability. We aimed to provide real-life examples

to support our arguments, but we still would need

empirical research to support our ideas further.

Second, we postulate the ecosystem as a possible

solution for solving a complex problem, i.e., creating

a joint service offering in the realm of PD, but we do

not investigate if, or to what extent, the ecosystem

would be better than a market-based or hierarchical

approach to value creation. Such an investigation of

the “real value” of the value-creation setting would

further support the arguments provided.

REFERENCES

Adner, R. (2006). Match your innovation strategy to your

innovation ecosystem. Harvard Business Review,

84(4).

Adner, R. (2017). Ecosystem as structure: an actionable

construct for strategy. Journal of Management, 43(1),

39.

Alves, G., Wentzel-Larsen, T., Aarsland, D., & Larsen, J.

P. (2005). Progression of motor impairment and

disability in Parkinson disease. Neurology, 65(9),

1436–1441.

https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000183359.50822.f2

Autio, E., & Thomas, L. D. W. (2022). Researching

ecosystems in innovation contexts. Innovation and

Management Review, 19(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/

10.1108/INMR-08-2021-0151

Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG). (2022).

Volkswirtschaftliche Kosten von NCDs. Obsan-

Indikatoren. https://ind.obsan.admin.ch/indicator/mon

am/volkswirtschaftliche-kosten-von-ncds

Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG). (2023). Stark steigende

Kosten führen zu deutlich höheren Prämien im Jahr

2024. Medienmitteilungen. https://www.admin.ch/gov/

de/start/dokumentation/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-97

889.html

Chesbrough, H., Lettl, C., & Ritter, T. (2018). Value

Creation and Value Capture in Open Innovation.

Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(6),

930–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12471

Dattée, B., Alexy, O., & Autio, E. (2018). Maneuvering in

Poor Visibility: How Firms Play the Ecosystem Game

when Uncertainty is High. Academy of Management

Journal, 61(2), 466–498. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.

2015.0869

Ittner, C. D., & Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical

research in managerial accounting a value-based

management perspective. Journal of Accounting and

Economics, 32, 349–410.

Jacobides, M. G., Cennamo, C., & Gawer, A. (2018).

Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strategic

Scale-IT-up 2024 - Workshop on Emerging Business Models in Digital Health

844

Management Journal (John Wiley \& Sons, Inc.), 39(8),

2255–2276.

Kretschmer, T., Leiponen, A., Schilling, M., & Vasudeva,

G. (2022). Platform ecosystems as meta-organizations:

Implications for platform strategies. Strategic

Management Journal, 43(3), 405–424. https://doi.org/

10.1002/smj.3250

Lingens, B., Seeholzer, V., & Gassmann, O. (2023).

Journey to the Big Bang : How firms define new value

propositions in emerging ecosystems. Journal of

Engineering and Technology Management, 69(July),

101762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jengtecman.2023.101

762

Madden, B. J. (2020). Value Creation Principles: The

Pragmatic Theory of the Firm Begins with Purpose and

Ends with Sustainable Capitalism. John Wiley & Sons,

Incorporated.

Maicher, L., Lenoci, T., & Vetterling, D. (2023).

Controlling-Erkenntnisse beim Aufbau eines Business

Ecosystems. Controlling - Zeitschrift Für

Erfolgsorientierte Unternehmenssteuerung, 05, 33–38.

Malmi, T., & Ikäheimo, S. (2003). Value Based

Management practices - Some evidence from the field.

Management Accounting Research, 14(3), 235–254.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1044-5005(03)00047-7

Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of

Competition. Harvard Business Review, 71(3), 75–86.

Nerbel, J. F., & Kreutzer, M. (2023). Digital platform

ecosystems in flux: From proprietary digital platforms

to wide-spanning ecosystems. Electronic Markets,

33(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-023-

00625-8

NHS England. (2022). The healthcare ecosystem.

Introduction to Helthcare Technology. https://digital.

nhs.uk/developer/guides-and-documentation/introducti

on-to-healthcare-technology/the-healthcare-ecosystem

Pang, S. Y. Y., Ho, P. W. L., Liu, H. F., Leung, C. T., Li,

L., Chang, E. E. S., Ramsden, D. B., & Ho, S. L. (2019).

The interplay of aging, genetics and environmental

factors in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease.

Translational Neurodegeneration, 8(1), 1–11.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40035-019-0165-9

Parkinson Schweiz. (n.d.). Parkinson Schweiz.

https://www.parkinson.ch/

Pidun, U., Reeves, M., & Schüssler, M. (2020). Why Do

Most Business Ecosystems Fail? https://www.bcg.com/

de-de/publications/2020/why-do-most-business-

ecosystems-fail

Priem, R. L. (2007). A consumer perspective on value

creation. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 219–

235. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.23464055

Rappaport, A. (1981). Selecting strategies that create

shareholder value. Harvard Business Review,

May/Jun(3), 139–149.

Rappaport, A. (1998). Creating shareholder value : a guide

for managers and investors (Revised an). Free Press.

Ritala, P., Agouridas, V., Assimakopoulos, D., & Gies, O.

(2013). Value creation and capture mechanisms in

innovation ecosystems: A comparative case study.

International Journal of Technology Management,

63(3–4), 244–267. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.201

3.056900

Schreieck, M., Wiesche, M., & Krcmar, H. (2021).

Capabilities for value co-creation and value capture in

emergent platform ecosystems: A longitudinal case

study of SAP’s cloud platform. Journal of Information

Technology, 36(4), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/

02683962211023780

Talmar, M., Walrave, B., Podoynitsyna, K. S., Holmström,

J., & Romme, A. G. L. (2020). Mapping, analyzing and

designing innovation ecosystems: The Ecosystem Pie

Model. Long Range Planning, 53(4), 101850.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.09.002

Vetterling, D., & Baumöl, U. (2023a). Ecosystems als

Quelle kundenzentrierter Wertschöpfung - Konzepte

und Steuerungspotenzial. Controlling - Zeitschrift Für

Erfolgsorientierte Unternehmenssteuerung, 35(5), 4–

11.

Vetterling, D., & Baumöl, U. (2023b). Networked business

design in the context of innovative technologies: Digital

transformation in financial business ecosystems.

Journal of Financial Transformation - Capco Institute,

58, 72–81.

Watson, R. T. (2021). Capital, Systems, and Objects.

Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-

15-9418-2

Well Gesundheit AG. (2023). Über uns. https://www.

well.ch/uber-uns/

Advocating for Harnessing the Power of Ecosystems in Healthcare: The Case of an Ecosystem in the Realm of Parkinson’s Disease - A

Position Paper

845