A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential

Efficiency Issues

Bilal Maqbool

1 a

, Farzaneh Karegar

2 b

and Sebastian Herold

1 c

1

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Faculty of Health, Science and Technology, Karlstad University,

Karlstad, Sweden

2

Department of Information Systems, Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden

Keywords:

Usability Evaluation (UE), Digital Health (DH), eHealth, Survey, Questionnaire.

Abstract:

Context: Usability is a major factor in the acceptance of digital health (DH) solutions. Problem: Despite

its importance, usability experts have expressed concerns about the insufficient attention given to usability

evaluation in practice, indicating potential efficiency problems of common evaluation methods in the health-

care domain. Objectives: This research paper aimed to analyse industrial usability evaluation practices in

digital health to identify potential threats to the efficiency of their application. Method: To this end, we

conducted an online survey of 144 usability experts experienced in usability evaluations for digital health ap-

plications. The survey questions aimed to explore the prevalence of techniques applied, and the participants’

familiarity and perceptions regarding tools and techniques. Results: The prevalently applied techniques might

impose efficiency problems in common scenarios in digital health. Participant recruitment is considered time-

consuming and selecting the most appropriate evaluation method for a given context is perceived difficult.

The results highlight a lack of utilisation of tools automating aspects of usability evaluation. Conclusions:

A more widespread adoption of tools for automating usability evaluation activities seems desirable as well

as guidelines for selecting evaluation techniques in a given context. We furthermore recommend to explore

AI-based solutions to address the problem of involving targeted user groups that are difficult to access for

usability evaluations.

1 INTRODUCTION

Usability is an essential quality attribute of interactive

systems that not only ensures that the system is easy

to use and meets the users’ requirements (Rubin and

Chisnell, 2008) but also addresses other aspects such

as user satisfaction and accessibility (Zapata et al.,

2015). Users engaging with healthcare devices and

software can face various usability challenges, such as

difficulties related to text readability, cluttered or re-

dundant features, or limited support for multiple lan-

guages. The usability of digital health (DH) applica-

tions is an essential factor in their adoption and user

satisfaction (Huryk, 2010). DH technologies with

better usability can enhance patient safety, minimise

medical errors, improve healthcare outcomes, pro-

mote well-being and productivity, and reduce stress

for users, especially healthcare providers, such as

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1309-2413

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2823-3837

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3180-9182

nurses and physicians (Ventola, 2014; Alotaibi and

Federico, 2017). Lack of usability in such applica-

tions has been shown to cause patient frustration lead-

ing to problems in self-management of chronic dis-

eases (Matthew-Maich et al., 2016), increased costs

for training the use of applications for healthcare pro-

fessionals (Cresswell and Sheikh, 2013; Middleton

et al., 2013), or medical errors and miscommunica-

tion in treatments (Kushniruk et al., 2016).

Evaluating the usability during the development

of DH applications is therefore widely considered

an important task (Broderick et al., 2014; Solomon

and Rudin, 2020). Nonetheless, designing and im-

plementing highly usable DH applications is chal-

lenging. Our recent interview study with practition-

ers (Maqbool and Herold, 2021) and systematic liter-

ature review (SLR) (Maqbool and Herold, 2023) sug-

gested that problems with establishing high usability

DH applications might be caused by limited budgets

for usability evaluations (UE) and/or inefficient eval-

uation techniques. Furthermore, in terms of gathering

Maqbool, B., Karegar, F. and Herold, S.

A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential Efficiency Issues.

DOI: 10.5220/0012344400003657

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2024) - Volume 2, pages 63-76

ISBN: 978-989-758-688-0; ISSN: 2184-4305

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

63

insights from healthcare usability experts, the relevant

studies were published in 2014 and 2015 and only

focused on Electronic Health Records (EHR) (Rache

et al., 2014; Ratwani et al., 2015). Further exploring

and studying current UE practices, as well as existing

challenges in the DH context, will assist in focusing

on concerns and developing solutions.

Therefore, in this paper, our goal is to assess the

state-of-the-practice of UE in DH and to explore po-

tential obstacles to their efficiency. To investigate this

issue further, we developed the following research

questions to further extend upon that finding:

• RQ.1: How are UE conducted for DH applica-

tions?

• RQ.2: Which factors potentially decrease the ef-

ficiency of UE in the context of DH?

RQ.1 aimed to understand the state-of-the-

practice of UE in DH, including a characterization of

the applied methods as well as the experts involved

in UE. RQ.2 was built on RQ.1 by analysing the sta-

tus quo of UE in DH w.r.t. potential efficiency issues

associated with the explored characteristics.

The remaining paper is organised as follows: Sec-

tion 2 introduces key terms and concepts relevant to

the study; Section 3 reviews existing literature; Sec-

tion 4 describes the research method employed; Sec-

tion 5 presents the findings; Section 6 offers an analy-

sis of the results, implications, and recommendations;

and Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines future

research directions.

2 BACKGROUND: USABILITY

AND ITS EVALUATION

Usability is defined by ISO 9241-11 as the ease-of-

use of a system for a defined user group performing

specific actions to accomplish specified goals with ef-

fectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specific

context (ISO, 2018).

It is a multifaceted quality attribute that can be

refined according to different aspects of a system’s

user experience. Table 1 presents a usability charac-

teristic taxonomy unifying categorisations defined by

Nielsen (Nielsen, 1994), ISO 9241-11 (ISO, 2018),

and ISO 25010 (ISO, 2011).

There are different evaluation approaches to en-

sure a system’s usability. In this regard, four gen-

eral UE types are commonly distinguished in litera-

ture (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008). Exploratory testing

assesses how effective preliminary design concepts

are and whether they need further improvement. As-

sessment or summative testing occurs later in soft-

ware development when software is more complete to

assess how well users can perform tasks related to the

software’s intended use. Validation testing involves

evaluating how a product measures up against prede-

termined usability standards or benchmarks, usually

later in the development cycle. Comparative testing

involves evaluating two or more design concepts at

any stage in the development cycle to identify which

one performs better in terms of usability. These types

of evaluation are each best suited for different stages

of the development cycle (e.g., validation testing for

late system testing (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008)) and

are hence often used in combination.

Many UE methods are available, which can be

used either in isolation or in combination (Maramba

et al., 2019). These UE methods can be used for UE

types. We listed some well-known UE methods as

follows:

• Questionnaires are often used to gather feedback

from users about their satisfaction and perceptions

of the system’s usability.

• Task-related metrics are often used to measure

effectiveness and efficiency, such as whether a

study’s participants completed a task and how

long it took.

• ‘Think-Aloud’ protocols are used to ask partici-

pants to express their thoughts, opinions, and feel-

ings about the system while or after performing a

task.

• Interviews are one-on-one (un/semi)structured

discussion that offers in-depth knowledge of par-

ticipants’ requirements, pain points, and needs.

• Heuristic evaluation is a method that is used to

evaluate an application’s usability by experts to

determine if it complies with accepted usability

standards (the “heuristics”).

• Focus group discussions are conversations with

a group of people who have similar backgrounds

or experiences about how they believe the system

can be used and whether they have any concerns

about it.

Furthermore, UE tools and platforms have been

developed to help automate various steps of the us-

ability testing process (Namoun et al., 2021). These

tools and platforms can be categorised based on their

functionality and use cases, as listed below:

• Participant recruitment tools assist in finding

and screening suitable participants for usability

tests. Examples include UserTesting

4

.

4

https://www.usertesting.com/

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

64

Table 1: Usability characteristics as categorized by Nielsen (Nielsen, 1994), ISO 9241-11 (ISO, 2018), and ISO 25010 (ISO,

2011).

Usability

characteristics

Definition Reference model

Accessibility The degree to which individuals with varying competencies and char-

acteristics can utilize a system or product to accomplish a particular

goal within a specific context.

ISO 25010

Aesthetics The level to which a user interface enables a satisfying and enjoyable

interaction.

ISO 25010

Appropriateness /

Usefulness

The capacity for users to assess the appropriateness of a product or

system for their requirements or needs.

ISO 25010

User error protec-

tion

The system should minimise errors and allow users to easily recover

from mistakes without severe consequences.

ISO 25010, Nielsen

Learnability The system should have a low learning curve, allowing users to

quickly become proficient and start accomplishing tasks with ease.

ISO 25010, Nielsen

Operability The software product’s ability to empower the user to operate, man-

age, and control it.

ISO 25010

Effectiveness The level of precision and comprehensiveness with which users ac-

complish predefined objectives.

ISO 9241-11

Efficiency Efficiency is a key aspect of systems usability. Once a user has mas-

tered the system, they should be able to achieve a high level of pro-

ductivity.

ISO 9241-11, Nielsen

Satisfaction The system should provide a pleasant user experience, creating a

sense of comfort and acceptability of use that results in subjective

satisfaction for users.

ISO 9241-11, Nielsen

Memorability The system should be memorable, allowing occasional users to re-

sume using the system after a period of inactivity without having to

relearn everything.

Nielsen

• Task and scenario setup tools help to define

tasks, scenarios, and questions for participants to

complete during the usability tests. Examples in-

clude Optimal Workshop

5

.

• Data collection tools can record user interactions,

such as clicks, scrolls, and keystrokes, during the

usability test. Examples include Hotjar

6

, Look-

back

7

, and UserTesting

4

).

• Data analysis tools can analyse recorded data,

generating insights and visualisations to evaluate

usability. Examples include Optimizely

8

, Hot-

jar

6

), and Optimal Workshop

5

).

Such tools and platforms can potentially improve the

efficiency and effectiveness of the UE process while

offering valuable insights into the usability of evalu-

ated applications.

3 RELATED WORK

This section provides an overview of previous survey

studies on usability and challenges in UE in practice,

5

https://www.optimalworkshop.com/

6

https://www.hotjar.com/

7

https://www.lookback.com/

8

https://www.optimizely.com/

both in general contexts and specifically within the

digital healthcare domain.

Several studies have explored the evolution of us-

ability, focusing on the awareness and familiarity with

concepts and practices globally. Results show that

awareness and familiarity can differ a lot; while re-

search indicates positive trends in developing coun-

tries (Lizano et al., 2013), findings from some other

countries suggest a need for enhanced awareness and

skill in UE (Ashraf et al., 2018).

Ardito et al. emphasised the resource-intensive

aspect of user involvement in UE and cited heuris-

tic evaluations as a cost-effective alternative requir-

ing minimal resources and training (Ardito et al.,

2014). However, the lack of standardized contextual

UE methods and metrics remains a challenge (Ardito

et al., 2011). Automated tools like AChecker are used

for accessibility validation to mitigate resource limi-

tations (Ardito et al., 2014). Developers often priori-

tise functionality, amplified by limited user availabil-

ity for evaluations. The survey highlighted a need for

cost-effective UE methods.

Lizano et al. unveiled significant challenges in in-

volving users in UE within software development or-

ganizations, coupled with limited resources and issues

with developers’ mindset in terms of usability (Lizano

et al., 2013).

Roche et al. found that the selection and applica-

A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential Efficiency Issues

65

tion of UE methods among French professionals var-

ied, influenced by factors like experience, education,

and industry (Rache et al., 2014). Common meth-

ods included scenario and task-based evaluations, ob-

servation, interviews, heuristic evaluations, question-

naires, and cord sorting, while only 4% used auto-

mated tools. The predominance of methods involv-

ing end-users reflects a user-centred design (UCD)

approach.

Ratwani et al. conducted a study of EHR sup-

pliers with the objective of examining the integration

of UCD principles into their EHR development pro-

cesses (Ratwani et al., 2015). They revealed that, de-

spite certification requirements mandating the use of

UCD processes, implementation is inconsistent. UE

challenges include recruiting volunteers with relevant

clinical knowledge for usability studies, and knowl-

edge gaps in understanding the appropriate number

of participants and evaluation processes for summa-

tive testing.

Ogunyemi et al. found that Nigerian software

companies often ignore the need for diverse and rep-

resentative user groups in UE, facing time and cost

challenges, and lacking focus on integrating usability

experts of varied skills and perspectives (Ogunyemi

et al., 2016).

Ashraf et al. survey software practitioners and

found the lack of HCI/usability professionals in most

organizations (Ashraf et al., 2018). Additionally, over

50% of the participants reported a lack of a dedi-

cated budget for managing usability-related activities

in their respective organizations.

Rajanen and Tapani analysed UE methods of

North American game companies, uncovering a pref-

erence for observations, scenario and tasks-based

evaluations, focus groups, questionnaires, interviews,

and think-aloud protocols, tailored for the gaming

sector (Rajanen and Tapani, 2018). Heuristic eval-

uations and walkthroughs were less common, and

no company used eye-tracking, though some consid-

ered its future use. Companies often utilised easily

accessible participant pools and predominantly con-

ducted evaluations in their offices. While the signifi-

cance of usability in enhancing gaming experiences

is recognised, its implementation is constrained by

costs, time, and expertise.

A survey showed the widespread use of think-

aloud protocols in both lab and remote usability tests

due to their real-time insights (Fan et al., 2020).

Concurrent think-aloud is preferred, but challenges

such as participant comfort and time-intensive anal-

ysis persist.

Inal et al. surveyed usability professionals’

work practices and found that questionnaires and

scenario/task-based evaluations were the frequently

employed methods (Inal et al., 2020). The study re-

ported an equal prevalence of UE conducted at cus-

tomer sites and in lab settings. The researchers also

found the use of focus groups, observations, heuris-

tic/expert evaluations, card sorting, and eye-tracking

evaluations. However, 73% of the participants did not

conduct remote UE, with only 17% reporting the use

of 1–3 tools for such evaluations. Usability profes-

sionals also faced resource constraints like time and

cost.

Existing literature outlines various UE practices

but lacks depth in the DH domain, especially regard-

ing threats to the efficiency of UE. Our study aimed

to fill this gap, offering an in-depth perspective on UE

practices and related potential efficiency challenges

specific to DH.

4 METHODOLOGY

We conducted an online survey to answer our research

questions and achieve our goal, as outlined in Sec-

tion 1.

4.1 Survey Design

The design of the survey study followed the ap-

proaches suggested by Kasunic (Kasunic, 2005), and

Mitchell and Jolley (L Mitchell and M Jolley, 2010).

The survey had three different parts with a total of

19 questions

9

.

The introductory and screening part included

survey information, obtaining informed consent, and

screening participants based on a non-leading manda-

tory screening question to determine whether volun-

teers meet the eligibility criteria (see Section 4.2 for

more details on eligible participants).

The demographic part consisted of eight ques-

tions designed to know participants better regarding

their demographics and previous experiences in as-

sessing and ensuring the usability of DH applications

(see Part II of survey questionnaire

9

). The questions

asked participants about their gender, age, job posi-

tion or title, and their experiences regarding UE of

DH apps. They were also asked what types of DH

technologies they have evaluated for usability.

The main part included ten UE-related questions.

This part focused on UE methods, tools, and tech-

niques to understand how usability experts conduct

UE in DH. Furthermore, we explored to what extent

9

Survey Repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.

10396862

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

66

different usability characteristics were covered in UE

that our participants performed. The last two ques-

tions inquired about the overall perceived benefits and

challenges encountered during conducting UE of DH

applications.

The questionnaire was developed using the knowl-

edge gained during our recent SLR work (Maqbool

and Herold, 2023). The questionnaires included both

fixed-alternative questions (such as true/false, mul-

tiple choice, checkbox, and rating scale) and open-

ended free-text responses. It included an initial set of

fixed-alternative question response options based on

relevant knowledge (Rubin and Chisnell, 2008; Maq-

bool and Herold, 2023) and grey literature (Morgan

and Gabriel-Petit, 2021; Wright, 2020). Almost every

question included open-text fields to accommodate a

broader range of responses (refer repo. for details

9

),

allowing participants to share answers not in the pre-

defined response options.

A pilot study with four participants was performed

before distributing the survey. All the pilot partici-

pants were researchers, with two also having profes-

sional experience in developing apps for DH. Pilot

tests helped analyse the survey design, the relevance

of the research questions, survey questions, survey

completion time, and survey complexity. The pilot

tests led to some modifications of the questionnaire,

such as adding matrix-based response choices, sim-

pler terminology, and clearer wording of questions.

4.2 Target Audience and Recruitment

We targeted individuals with professional experience

in assessing and ensuring the usability of DH appli-

cations. Prolific

10

platform was used to find and re-

cruit eligible participants. We mainly used two of the

Prolific filtering functions for the short prescreening

survey, including the knowledge of Functional/Unit

testing, Responsive/UI design, A/B testing, and UX

and the relevant employment sectors (like Medicine,

IT, Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathemat-

ics, Social Sciences, etc.) to increase the chance of

reaching relevant people. A one-question prescreen-

ing survey was conducted on Prolific to identify us-

ability experts with experience assessing and ensuring

DH app usability (see Part I of survey questionnaire

9

).

The prescreening survey filtered 162 eligible partici-

pants from 1000 to be invited for the main survey. The

participants who completed the prescreening survey

(n=1000) and the ones who answered the main survey

(n=138) on Prolific were compensated w.r.t. £9.00 per

hour for their participation in each survey. The sur-

10

A participant recruiting platform, https://www.prolific.

co/.

Figure 1: Distribution of participants by age group and gen-

der.

vey, available online in English, was conducted over

a two-month period from September to October 2022.

On average, participants took 11 minutes to complete

the main survey questionnaire.

In parallel, we also announced the survey on

LinkedIn, Facebook groups, Reddit, and Research-

Gate and informed peer contacts via our university

mailing lists. We only got six more participants

through these channels and ended with 144 valid re-

sponses in total.

4.3 Ethical Approval

The reported survey has received the ethical approval

of the local ethics advisor at Karlstad University (file

number: HNT 2022/459). Participation in the study

and answering questions was voluntary and optional,

and reporting was anonymous. Participants could pro-

ceed upon reading the study information, getting in-

formed about their rights, and giving their consent.

4.4 Replication Package

We have created a repository

9

containing all the sur-

vey responses to facilitate replication and share our

work with the academic and industrial community.

Furthermore, the survey results are also presented in

a detailed tabular form in the repository

9

.

5 RESULTS

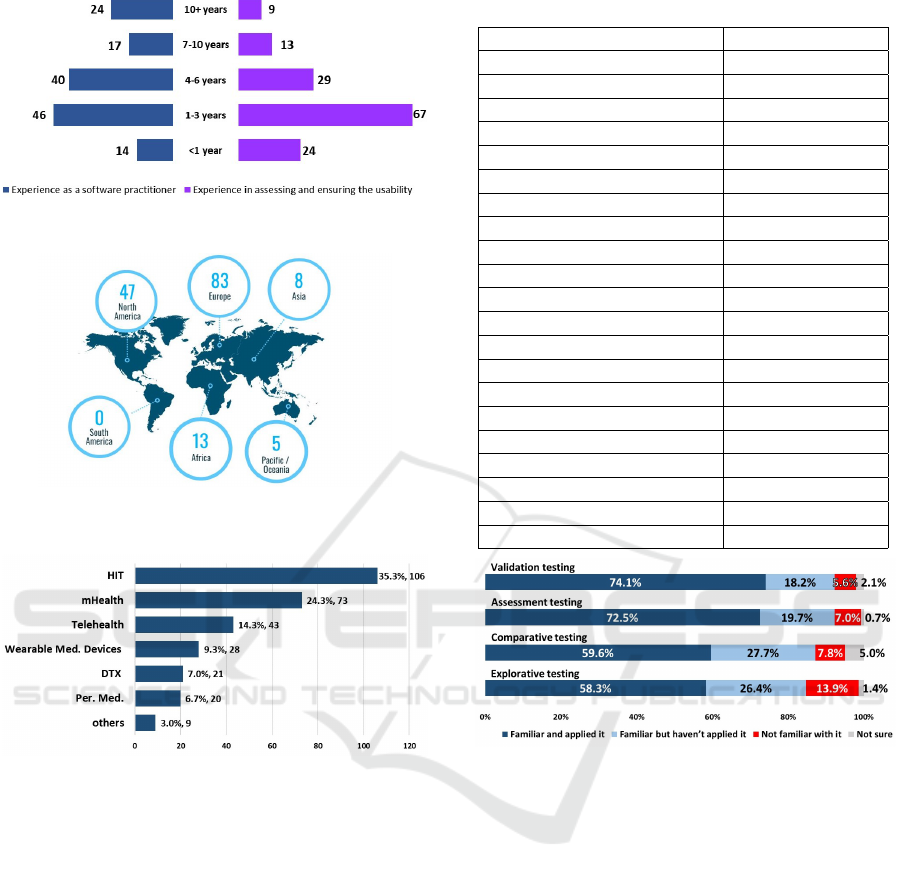

5.1 Respondents’ Demographics

The majority of respondents (82%) were male, with

only 18% identifying as female. Additionally, the

largest proportion of respondents (45%) fell within

the 25-34 age range, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The study participants showed a broad spectrum

of experience working in the health tech industry as

A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential Efficiency Issues

67

Figure 2: Experience in the health tech industry.

Figure 3: Participant’s working experience in the health

tech industry across the globe.

Figure 4: Number of participants evaluated DH technolo-

gies for usability.

IT or usability professionals, spanning from entry-

level to senior roles. Furthermore, the majority of

participants had prior experience in assessing and en-

suring the usability of DH applications, ranging from

early to mid-level experience (Figure 2). This also

highlights the diversity of expertise and experience

within the sample.

The geographical distribution of participants

shows a clear focus on Europe and North Amer-

ica (Figure 3).

Table 2 shows participants’ prevalent roles and re-

sponsibilities in UE in DH. Most participants were

software developers, followed by software testers, de-

signers, strategists, and researchers.

Furthermore, participants showed expertise in

evaluating and ensuring the usability of various DH

technologies, with HIT and mHealth being among the

most frequently evaluated technologies (Figure 4).

Table 2: Roles and responsibilities involved in UE in DH.

Roles and Responsibilities # of Participants

Designers

Interaction Designer 14

Product Designer 28

Prototyper 22

UI Designer 37

UX Designer 27

Researchers

User Researcher 26

UX Researcher 13

UX Writer 5

Software Developer 85

Software Tester 69

Strategists

Content Strategist 11

Information Architect 22

UX Architect 11

UX Lead 10

UX Manager 10

Usability-Testing Specialist 26

Prefer not to disclose 3

Others 14

Figure 5: Familiarity with UE types.

5.2 UE Types

The study findings showed that UE is covered in all

development phases, with a particular emphasis on

the system testing phase, as reported by 71% of the

participants who conducted UE activities during this

phase. 53% of participants performed UE during

unit/integration testing, 50% during production, and

49% during the design phase.

Compared to comparative and exploratory testing,

validation and assessment testing were utilised by the

majority of participants for UE of DH technologies

(see Figure 5). Some participants were familiar with

UE types but had not used them (23% on average) or

were unfamiliar with them (8% on average).

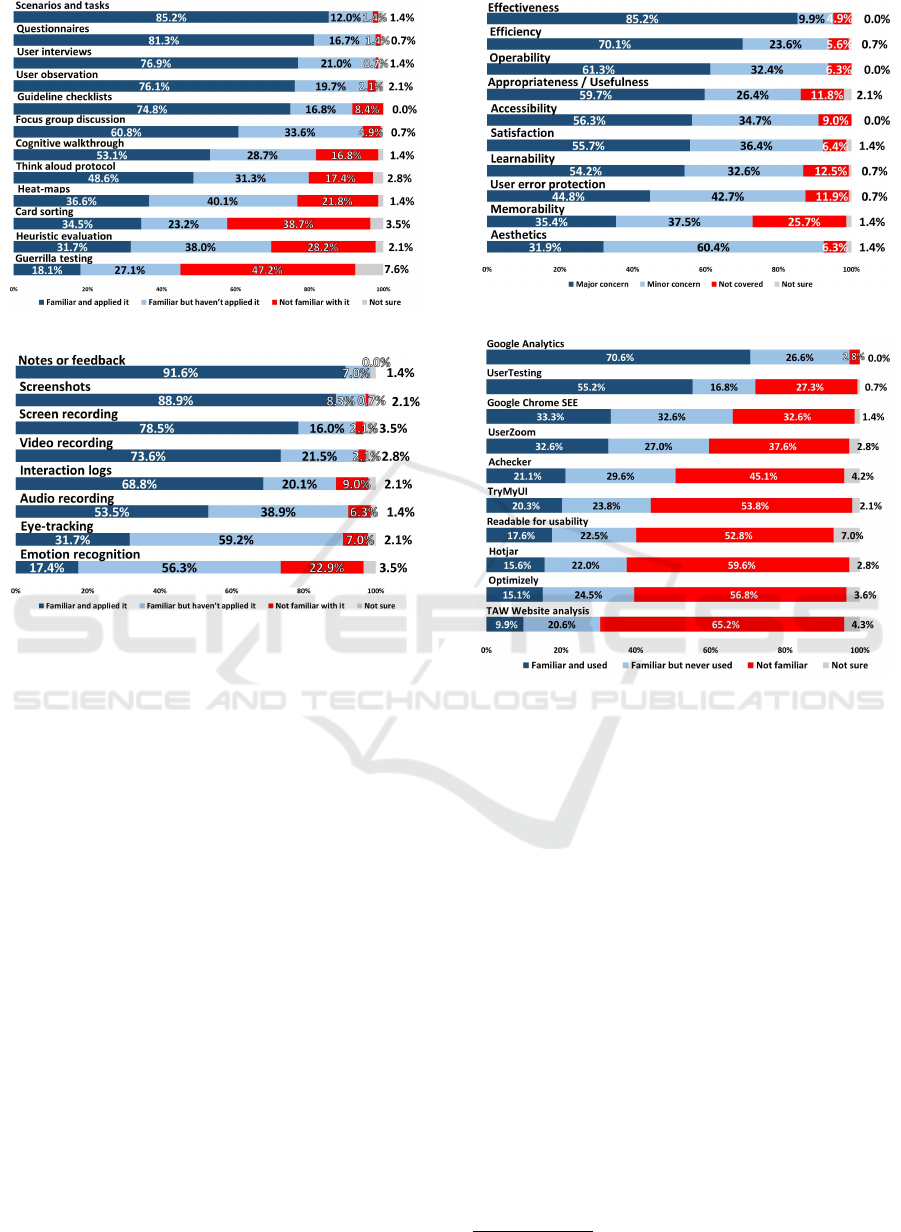

5.3 UE Methods

Most participants were familiar with various UE

methods, which they had applied in a DH context.

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

68

Figure 6: Familiarity with UE methods.

Figure 7: Familiarity with data recording methods.

The most known and commonly used UE meth-

ods were scenarios and tasks-based testing, question-

naires, user interviews, user observation, guideline

checklists, focus group discussion (FGD), cognitive

walkthroughs, and think-aloud protocols. Guerrilla

testing, heuristic evaluation, card sorting, and heat

maps were infrequently used, despite participants’ re-

ported familiarity with them (see Figure 6). A consid-

erable proportion of participants reported being unfa-

miliar with many of these methods.

Participants employed a wide range of meth-

ods for collecting and recording usability evaluation

data, as shown in Figure 7. Most participants used

notes/feedback, screenshots, and screen/video record-

ings, nearly 79% and 66% never used emotion recog-

nition and eye-tracking. One participant shared their

perspective on eye-tracking, asserting that although

they have used it, they still remain skeptical about its

validity and value. Another participant stated the im-

portance of emotional recognition/feedback and how

replacing phrases could affect system usability and

user emotions.

The majority of participants used moderated ap-

proaches both in in-person and remote UE (103 and

100, respectively); unmoderated approaches were less

common (49 and 60 participants, respectively).

Figure 8: Usability characteristics coverage.

Figure 9: Familiarity with top 10 tools or platforms for UE

5.4 Usability Characteristics

The survey responses revealed that participants per-

ceived effectiveness and efficiency as primary con-

cerns usability characteristics of UE (Figure 8). No-

tably, 26% of survey participants did not assess the

memorability characteristic in their careers.

5.5 UE Tools

The study found that most usability experts were un-

familiar with most of the UE tools and technolo-

gies we listed in the questionnaire (see Figure 9).

The listed tools and technologies were derived from

UE literature (Maqbool and Herold, 2023) and web

searches. Only a few platforms and tools, such as

Google Analytics

11

, UserTesting

4

, Chrome SEE (un-

available now), and UserZoom (now part of UserTest-

ing), were used by more than 30% of the participants.

Overall, most respondents believed that using UE

tools or technologies has benefits (Figure 10). The

11

https://developers.google.com/analytics

A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential Efficiency Issues

69

Figure 10: Benefits of using tools in UE.

most agreed-upon benefit among the predefined lists

of benefits in the question, with 85% of participants

agreeing with it (with around 35% of them indicating

strong agreement), is that using these tools or plat-

forms can make UE more effective, suggesting an im-

provement in the overall quality of the evaluation pro-

cess and the ability to identify usability issues.

Participants also agreed that using tools can make

the UE process more efficient, indicating a reduction

in the time and effort required to complete UE activ-

ities. The level of agreement was high for most other

statements about the potential benefits of using tools.

Interestingly, in total, 54% of participants agreed

(with around 15% of them indicating strong agree-

ment) that using UE tools or technologies can reduce

the need to engage usability experts to carry out UE.

In summary, the findings indicate that using UE tools

or platforms is considered beneficial, however, the ac-

tual use in practice is not very common.

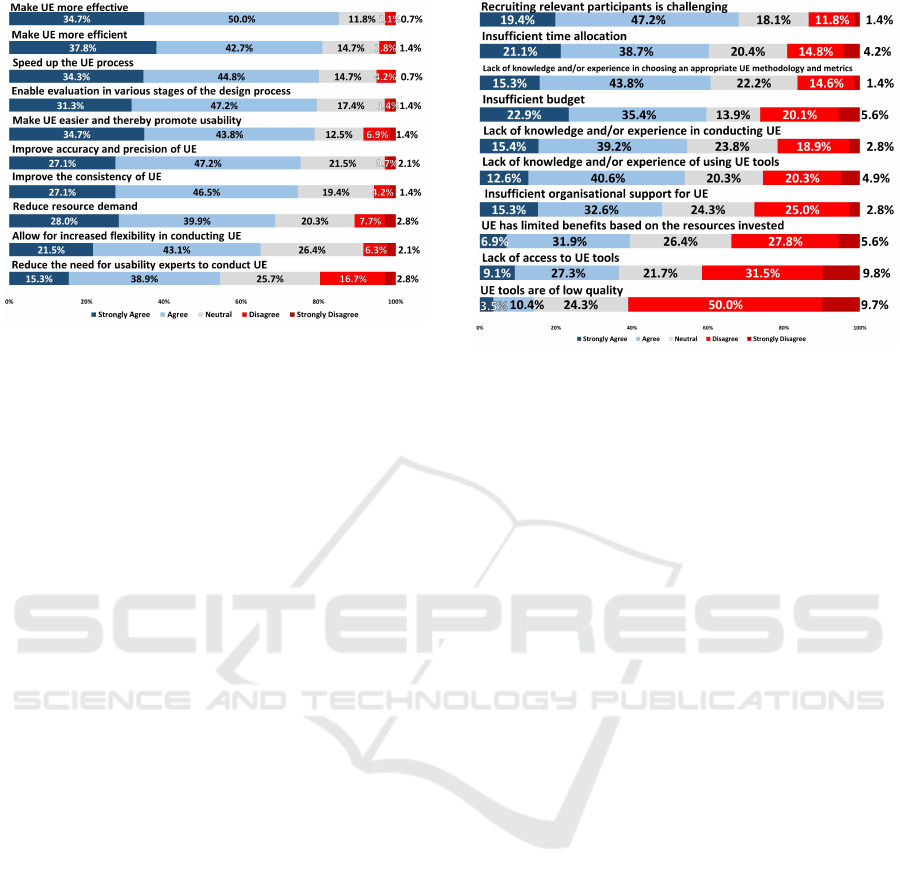

5.6 Perceived UE Benefits and

Challenges

The perceived benefits of conducting UE were found

by examining how participants ranked the benefits of

performing UE in terms of improving the usability of

DH applications. According to 34% of respondents,

UE significantly improves the application’s usability

and impacts the customer experience. Furthermore,

47% of respondents believed that evaluating the DH

application’s usability significantly impacts product

experience. However, 19% of respondents acknowl-

edged that while UE is beneficial, its impact on im-

proving or promoting the application’s usability may

be limited for certain products.

A majority of respondents (68%) found recruiting

relevant usability study participants to be difficult (see

Figure. 11). Moreover, in total, 60% of the respon-

Figure 11: Challenges of UE in DH.

dents felt that the allocated time for UE is insufficient.

Additionally, 59% of respondents believed that there

is a lack of knowledge and/or experience regarding

selecting a sound evaluation methodology and usabil-

ity metrics. Another major concern, according to 58%

of respondents, is the insufficient budget for UE.

More than half of the respondents believed that

there is a lack of knowledge and experience in con-

ducting UE (55%) and using related tools (53%). Fur-

thermore, 48% of the respondents felt that there is in-

sufficient organisational support for UE.

The study also highlighted a divergence in opin-

ions regarding the balance of resource investment

against the benefits of UE. While 39% of the respon-

dents perceived that the benefits of UE do not jus-

tify the resources invested, a slightly lower proportion

(33%) disagreed with this view, suggesting a belief in

the value of investment in UE. The 26% held a neutral

stance on this matter.

Most respondents believed there is no lack of

access to UE tools (41%) and agreed that market-

available UE tools are of good quality (60%).

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 RQ.1: Current Practices of UE in

DH

The diversity of roles found in our study is in line with

findings of previous research in other domains (Fan

et al., 2020; Hussein et al., 2014). Bornoe and Stage

argue that software developer and tester involvement

fosters a comprehensive grasp of user needs and en-

hances the design quality of DH software (Bornoe and

Stage, 2017).

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

70

The results regarding lifecycle phases in which

UE takes place provide evidence that UE is common

in all phases, which has been considered crucial for

developing user-centric products (Bergstrom et al.,

2011; da Silva et al., 2015; Bornoe and Stage, 2017;

Inal et al., 2020).

UE methods such as scenarios and tasks-based

methods, questionnaires, user interviews, and user

observation are pre-dominantly used, which is in line

with the existing literature on UE methods (Rache

et al., 2014; Rajanen and Tapani, 2018; Inal et al.,

2020; Zapata et al., 2015; Ansaar et al., 2020;

Paz and Pow-Sang, 2016; Schmidt and De Marchi,

2017; Yanez-Gomez et al., 2017; Ye et al., 2017;

Maramba et al., 2019). Heuristic evaluation, despite

being considered a versatile, rapid, and cost-effective

method (Ardito et al., 2014; Azizi et al., 2021), is

under-utilised in the DH sector, just like guerrilla

UE which can be efficient when UE is restricted by

limited financial resources (Nalendro and Wardani,

2020).

In DH, the preference leans towards moderated

UE, which also aligns with findings of previous sur-

vey findings (Inal et al., 2020). These offer a deeper

exploration of the user’s journey and unveil nuanced

insights that unmoderated evaluations might over-

look.

Our findings related to prioritised usability char-

acteristics align with existing knowledge in the liter-

ature; effectiveness and efficiency of use are the most

commonly considered aspects (Zapata et al., 2015;

Zahra et al., 2018; Liew et al., 2019). It also con-

firms findings from previous studies in DH, stressing

operability as a primary aspect (Zapata et al., 2015;

Ansaar et al., 2020). We find the low scores for

memorability surprising, as it could be expected in

the context of interest, and given an ageing society,

this attribute plays an important usability role. The

analysis of the findings showed that the evaluation of

specific usability characteristics did not vary signif-

icantly across different types of DH systems appli-

cations, although one can assume that the relevance

of certain characteristics, e.g. operability, differ for

them. We assume that the use of known methods and

standardised techniques such as out-of-the-box ques-

tionnaires are not sufficiently tailored to address such

differences.

Participants in our study acknowledged the advan-

tages of tools for automating aspects of UE but dis-

played a notable lack of familiarity with them, echo-

ing trends identified in existing literature (Paz and

Pow-Sang, 2016; Maramba et al., 2019; Rache et al.,

2014). The gap between the high availability of tools

on one hand but low familiarity with them on the

other, while expressing appreciation for their useful-

ness and quality in general, needs further exploration

and might be addressed by a systematic overview of

tools and their capabilities in practice.

The survey responses confirmed many challenges

in UE in DH that were expressed in previous surveys

in UE in general: difficulty of recruiting partici-

pants (Inal et al., 2020; Ogunyemi et al., 2016; Ardito

et al., 2014; Lizano et al., 2013; Ratwani et al., 2015),

limited time for UE (Lizano et al., 2013; Inal et al.,

2020; Fan et al., 2020; Ogunyemi et al., 2016; Raja-

nen and Tapani, 2018), budget constraints (Lizano

et al., 2013; Ashraf et al., 2018; Ardito et al., 2014;

Ogunyemi et al., 2016; Rajanen and Tapani, 2018;

Inal et al., 2020), and lack of knowledge regard-

ing choosing methodologies and designing evalu-

ations (Inal et al., 2020; Ratwani et al., 2015; Raja-

nen and Tapani, 2018). These findings are, as such,

not surprising but confirm issues previously found in

other general and DH domains, too. Any solutions to

address these aspects, in general, do not seem to have

avoided those issues in the DH domain.

6.2 RQ.2: Potential Factors Influencing

UE Efficiency

In the following, we discuss potential efficiency is-

sues and areas of improvement, as suggested by the

insights gathered from the survey results. This allows

us to hypothesize about underlying factors and pro-

pose potential strategies for improvement.

6.2.1 UE Methods

The UE methods that the survey respondents ex-

pressed the highest degree of familiarity and usage

with have their pitfalls when it comes to using them

efficiently. Task and scenario-based methods, for

example, require representative tasks formulated in

clear and unambiguous ways and considerations re-

garding task complexity, order, and the cognitive load

they cause; Crafting an effective questionnaire, espe-

cially for complex tasks, is not straightforward. The

emphasis on question precision, clarity, and neutrality

is important to ensure data integrity.

All of this is challenging in a DH setting in which

the target user group is highly heterogeneous, and as-

pects like age or use-affecting conditions need to be

considered in the UE design. Even though we did not

ask about the rationale of their responses, we think

that these aspects are partially responsible for the high

level of agreement related to the lack of knowledge re-

garding selecting UE methods. This aspect might be

amplified by the confirmed challenge of having too

A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential Efficiency Issues

71

limited time and/or insufficient budget for UE, as this

might affect the careful design of the evaluations as

well. The diversity of evaluator roles involved in UE,

including roles implying that an education in usabil-

ity is unlikely possibly aggravate this issue. Previ-

ous research stressed that, for example, programmers

struggle with evaluating usability (Bornoe and Stage,

2017).

In many methods, the analysis of data poses a

large part of the overall effort. In particular, quali-

tative data analysis causes a lot of manual work. De-

spite advances in (AI-based) tooling to assist humans

in this task, the survey does not show that these tools

are widely used. This shows further potential to in-

crease efficiency in UE in general and in DH specifi-

cally.

We found that usability experts in the DH in-

dustry generally prefer moderated UE over unmod-

erated ones. While unmoderated approaches re-

duce the effort on the side of the evaluator and

hence can improve efficiency, they have certain draw-

backs (Hertzum et al., 2014). A distraction-free set-

ting is crucial to gathering accurate results, and in-

structions and tasks have to be clearly described to

avoid misinterpretations in the absence of real-time

clarifications. If these conditions can be ensured (to a

practical extent), and particularly when the benefits of

moderated approaches, such as direct interaction and

adaptability, are not required for the specific use case,

unmoderated approaches can be an effective means to

increase efficiency.

6.2.2 Involvement of Users in UE

A problematic tension is visible in the results related

to the involvement of users in UE. The predominantly

used methods, such as scenario- and task-based UE,

require quite intense collaboration with users of the

system under evaluation. Furthermore, the results

suggest that such evaluation might be repeated dur-

ing the development lifecycle. At the same time, sur-

vey respondents agreed with challenges in participant

recruitment. We believe that this might be a particu-

larly pronounced issue in DH because there might be

application areas in which involving the relevant tar-

get groups, such as patients with certain conditions or

suffering from certain diseases, might be infeasible,

impossible, or unethical. This situation poses hence a

threat to the efficiency of UE.

It might therefore be advisable to check whether

some user evaluations along an application lifecycle

could be executed using less user-intense methods,

such as heuristic evaluation or guerrilla testing, re-

ducing the total effort for recruiting users and improv-

ing efficiency. However, heuristic evaluation requires

experts with specialised knowledge, and the absence

of such experts can be counter-productive. The use

of artificial intelligence for simulating the behaviour

of user groups that are hard to recruit is another po-

tential way of improving efficiency. Some aspects

of UE, such as user interface testing, could, in some

instances, be performed through a trained model of

target group behaviour before evaluations with actual

users are executed, reducing the recruitment effort. To

our knowledge, though, such tooling does not exist

yet. In a similar vein, the use of unmoderated ap-

proaches could improve efficiency by reducing the ef-

fort needed to execute UE.

6.2.3 Roles and Responsibility in UE

The diversity of evaluators’ roles found in the study

demographic in UE of DH applications is highlighted

by the active participation of roles like software devel-

opers and testers. These roles, generally defined in the

broader software development domain, are becoming

increasingly involved in UE, indicating a shift in de-

velopment practices. Moreover, witnessing real-time

user struggles with their codes (application) (Bor-

noe and Stage, 2017), can shift developers’ focus

from a purely technical aspect to one valuing usability

and user experience (Ardito et al., 2014; Bornoe and

Stage, 2017), potentially triggering an organizational

shift that balances technical and user experience as-

pects.

Nevertheless, these advantages do not come with-

out potential concerns. Despite their invaluable tech-

nical input, there’s a risk of overreliance on develop-

ers and testers and that their feedback might over-

shadow user-centric considerations, a gap filled by

UX designers/researchers and usability specialists. It

may indicate that these professionals need more user

experience (/usability) training and resources, but de-

velopers sometimes struggle to identify and evalu-

ate usability problems despite training (Bornoe and

Stage, 2017). In UE, collaboration is essential; a bal-

anced product that addresses technical and user con-

cerns can be achieved by combining technical and

user-focused insights.

6.2.4 Evaluation Stages

Continuous UE is crucial for crafting easy-to-use

DH applications, promoting broader adoption among

healthcare professionals and patients, and ensuring

efficient patient management and improved health

outcomes (Bygstad et al., 2008). In most cases,

UE is conducted when apps have been designed and

built (see Section. 5.2); this indicates that the DH sec-

tor still needs more continuous UE. The expressed

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

72

challenges of limited time and budget for UE imply

whether these evaluations are performed sufficiently

carefully in all phases. As expressed in previous re-

search, there is a tendency to prioritize functionality

over user experience often results in a reactive ap-

proach to usability, treating it as an afterthought ad-

dressed once issues emerge (Lauesen, 1997; Nugraha

and Fatwanto, 2021), which could explain these re-

sponses.

The efficiency of UE is also influenced by its

scope, varying from an interface design focus to en-

compassing the entire user journey. The survey did

not dive into the details of the scope of UE in dif-

ferent phases to keep the survey length manageable,

however, investigating the level of UE detail in dif-

ferent phases might be useful to investigate efficiency

issues further.

6.2.5 Usability Characteristics

The results did not show significant differences for

different types of applications in DH related to the pri-

marily evaluated usability characteristics. This seems

surprising as, for example, an electronic health record

system, tasked with managing precise and readily

available patient data, would prioritise effectiveness

and error-free operation, while a wellness app might

focus more on user satisfaction. These results might

pose the question of whether UE always takes the

right usability characteristics into account, which,

in turn, poses a threat to efficiency. This requires

particularly careful consideration when several target

groups are affected, as common in DH applications

which are used both by healthcare professionals and

patients.

Memorability sticks out from the results as a us-

ability characteristic that, in comparison, is neglected

quite often. Despite the relevance of applications for

healthcare professionals and individuals with chronic

diseases or other long-lasting conditions, many users

might use many DH applications sporadically and

may benefit from a high recognition value, in partic-

ular, if they are affected by memory decline. Not ex-

plicitly evaluating for memorability might therefore

be inefficient, as relevant goals of the target group are

not tested for.

6.2.6 Usage of Tools

The survey result indicates a discrepancy between the

awareness of the potential benefits of using tools for

automating steps in UE and their actual use. We be-

lieve that a closer collaboration between researchers,

tool vendors, and practitioners is required to provide

a clearer view of the support of UE methods through

tools, to analyse the capabilities and limitations of

tools, and to educate end-users of such tools. More-

over, research should explore applications of modern,

general-purpose tools, such as AI-based qualitative

data analysis, in the context of UE.

6.3 Implications and Recommendations

The key findings from the survey on UE of DH ap-

plications suggest the following implications and rec-

ommendations for DH practitioners and researchers:

• Despite the tight time and budget constraints,

practitioners need to spend sufficient time on UE

design and adaptation to the heterogeneous tar-

get user groups in DH. This helps avoid evalua-

tions that cannot be efficiently performed involv-

ing these user groups.

• Recruiting relevant participants is difficult, in

some cases impossible or unethical. Practition-

ers should investigate if UE, in some phases, can

be partially replaced by heuristic evaluations with

system experts, guerilla testing, or card sorting.

Research should work on technologies, e.g. based

on AI, to support strategies that reduce the effort

for human participants.

• A diversity of roles, including software develop-

ers and testers, is involved in UE in DH, which

is desirable. Building up UE knowledge in staff

such that experts are available, and capable of se-

lecting appropriate and efficient UE methods is

crucial. Researchers and experienced practition-

ers should provide a clear picture of when to pre-

fer which methods and how to adapt them based

on scenario, domain, and target user group.

• Practitioners should clarify the degree of rele-

vance of usability characteristics in a given sce-

nario, and select and tailor appropriate UE meth-

ods accordingly. Researchers should also investi-

gate the impact of under-prioritised usability char-

acteristics (e.g., memorability and aesthetics) on

overall usability and user perception in DH.

• Practitioners should familiarise themselves with

available tools. More comprehensive tool

overviews are needed. Researchers should inves-

tigate obstacles to using those tools in practice,

and investigate the use of AI in building more ad-

vanced UE automation tools.

6.4 Threats to Validity

This section addresses the potential threats to the va-

lidity and reliability of the study.

A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential Efficiency Issues

73

External Validity: We utilised multiple distribu-

tion channels to ensure a diverse participant base for

our survey (Section 4.2). Despite these efforts, a sub-

stantial portion of the responses came from users on

Prolific. This raises concerns about the generalis-

ability of our findings. Our results, however, show

a diverse group of respondents with different profes-

sional backgrounds, experiences, and expertise (Sec-

tion 5.1). This diversity is encouraging, as it sug-

gests that the study represents the varied perspectives

of professionals in the field of DH usability evalua-

tion. Still, future studies should aim to gain partici-

pants from diverse recruitment sources to enhance the

external validity of the findings.

Construct Validity: The survey questions rely on

the participant’s ability to accurately recall their expe-

riences and practices in UE. There’s a potential threat

that some participants might not remember all the de-

tails accurately, leading to a recall bias. This could

especially impact questions such as, related to their

familiarity and use of UE practices. Furthermore, due

to subjective experiences, there’s a risk of participants

interpreting questions differently, posing a threat to

construct validity. As part of our pilot study and test

runs, we tried to refine the questionnaire to mitigate

these issues; clarify ambiguous questions, simplify

complex items, and add explanations to the question-

naire and their responses (Section 4.1). However, de-

spite these efforts, the potential for varied interpreta-

tions remains.

We acknowledged the potential limitation im-

posed by fixed-alternative questions. To mitigate

this, we incorporated the ‘Other’ option in almost

all such questions, enabling participants’ diverse per-

spectives with free-text responses to capture unlisted

responses (see Section 4.1). However, only a few par-

ticipants utilised open-text responses.

Internal Validity: Our discussion of the research

questions, in particular RQ.2, has in large part ex-

ploratory character in the sense that we are not imply-

ing a causal relationship between the responses and

any efficiency problems but explore potential reasons

through argumentation. Our exploration is a prelim-

inary step, further in-depth study will be required to

determine the causal relationships and their underly-

ing factors.

7 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

The survey study identifies prevalent UE methods in

DH, such as scenarios and tasks-based methods, and

highlights the under-utilisation of potentially efficient

methods like heuristic evaluation. It points out the

challenges in participant recruitment and the impor-

tance of choosing appropriate usability characteristics

before conducting UE. Additionally, it highlights us-

ability experts’ lack of familiarity with automated UE

tools.

Based on the findings, we provide a couple of

recommendations for practitioners to address poten-

tial efficiency issues, such as using considering us-

ing methods to reduce the effort for user recruitment

and participation, building up expertise in UE de-

sign, determining relevant usability characteristics be-

fore UE, and familiarising with UE automation tools.

Researchers should address efficiency challenges in

practice by addressing the problem of recruiting par-

ticipants in DH and investigating the use of AI-based

techniques for this and other steps of the UE process

more. Our findings support some aspects of previ-

ous studies conducted in DH and/or general domains

while offering new insights that can inform future re-

search directions and industry practices in DH.

This study, utilising a cross-sectional design, cap-

tures the participants’ perspectives at one specific

point in time. Future research can incorporate lon-

gitudinal studies to observe the evolving trends and

changes in UE practices in DH. While the study ex-

plored UE practice in DH, it did not delve into the

reasons behind certain findings, such as the lack of

awareness and utilisation of automated UE tools, or

the reasoning behind participants’ agreement or dis-

agreement with certain benefits or challenges. Future

research could involve follow-up interviews or focus

group discussions with participants to gain deeper in-

sights.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partly funded by Region V

¨

armland

through the DHINO project (Grant: RUN/220266)

and partly funded by Vinnova through the DigitalWell

Arena (DWA) project (Grant: 2018-03025).

REFERENCES

Alotaibi, Y. K. and Federico, F. (2017). The impact of health

information technology on patient safety. Saudi med-

ical journal, 38(12):1173.

Ansaar, M. Z., Hussain, J., Bang, J., Lee, S., Shin, K. Y., and

Woo, K. Y. (2020). The mhealth applications usabil-

ity evaluation review. In 2020 International Confer-

ence on Information Networking (ICOIN), pages 70–

73. IEEE.

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

74

Ardito, C., Buono, P., Caivano, D., Costabile, M. F.,

and Lanzilotti, R. (2014). Investigating and promot-

ing ux practice in industry: An experimental study.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

72(6):542–551.

Ardito, C., Buono, P., Caivano, D., Costabile, M. F.,

Lanzilotti, R., Bruun, A., and Stage, J. (2011). Us-

ability evaluation: a survey of software development

organizations. In SEKE, pages 282–287.

Ashraf, M., Khan, L., Tahir, M., Alghamdi, A., Alqarni, M.,

Sabbah, T., and Khan, M. (2018). A study on usability

awareness in local it industry. International journal of

advanced computer science and applications, 9(5).

Azizi, A., Maniati, M., Ghanbari-Adivi, H., Aghajari, Z.,

Hashemi, S., Hajipoor, B., Qolami, A. R., Qolami, M.,

and Azizi, A. (2021). Usability evaluation of hospital

information system according to heuristic evaluation.

Frontiers in Health Informatics, 10(1):69.

Bergstrom, J. C. R., Olmsted-Hawala, E. L., Chen, J. M.,

and Murphy, E. D. (2011). Conducting iterative us-

ability testing on a web site: challenges and benefits.

Journal of Usability Studies, 7(1):9–30.

Bornoe, N. and Stage, J. (2017). Active involvement of soft-

ware developers in usability engineering: two small-

scale case studies. In Human-Computer Interaction–

INTERACT 2017: 16th IFIP TC 13 International

Conference, Mumbai, India, September 25-29, 2017,

Proceedings, Part IV 16, pages 159–168. Springer.

Broderick, J., Devine, T., Langhans, E., Lemerise, A. J.,

Lier, S., and Harris, L. (2014). Designing health liter-

ate mobile apps. NAM Perspectives.

Bygstad, B., Ghinea, G., and Brevik, E. (2008). Soft-

ware development methods and usability: Perspec-

tives from a survey in the software industry in norway.

Interacting with computers, 20(3):375–385.

Cresswell, K. and Sheikh, A. (2013). Organizational issues

in the implementation and adoption of health infor-

mation technology innovations: an interpretative re-

view. International journal of medical informatics,

82(5):e73–e86.

da Silva, T. S., Silveira, M. S., and Maurer, F. (2015). Us-

ability evaluation practices within agile development.

In 2015 48th Hawaii International Conference on Sys-

tem Sciences, pages 5133–5142. IEEE.

Fan, M., Shi, S., and Truong, K. N. (2020). Practices and

challenges of using think-aloud protocols in industry:

An international survey. Journal of Usability Studies,

15(2).

Hertzum, M., Molich, R., and Jacobsen, N. E. (2014). What

you get is what you see: revisiting the evaluator effect

in usability tests. Behaviour & Information Technol-

ogy, 33(2):144–162.

Huryk, L. A. (2010). Factors influencing nurses’ attitudes

towards healthcare information technology. Journal

of nursing management, 18(5):606–612.

Hussein, I., Mahmud, M., and Tap, A. O. M. (2014). A

survey of user experience practice: a point of meet

between academic and industry. In 2014 3rd Interna-

tional Conference on User Science and Engineering

(i-USEr), pages 62–67. IEEE.

Inal, Y., Clemmensen, T., Rajanen, D., Iivari, N., Riz-

vanoglu, K., and Sivaji, A. (2020). Positive devel-

opments but challenges still ahead: A survey study on

ux professionals’ work practices. Journal of Usability

Studies, 15(4).

ISO (2011). Iso/iec 25010:2011. systems and software en-

gineering — systems and software quality require-

ments and evaluation (square) — system and software

quality models. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:

iso-iec:25010:ed-1:v1:en. Accessed: 09-10-2023.

ISO (2018). Iso 9241-11:2018. ergonomics of human-

system interaction — part 11: Usability: Definitions

and concepts. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:

9241:-11:ed-2:v1:en. Accessed: 09-10-2023.

Kasunic, M. (2005). Designing an effective survey. Techni-

cal report, Carnegie-Mellon Univ Pittsburgh PA Soft-

ware Engineering Inst.

Kushniruk, A., Nohr, C., and Borycki, E. (2016). Hu-

man factors for more usable and safer health infor-

mation technology: where are we now and where do

we go from here? Yearbook of medical informatics,

25(01):120–125.

L Mitchell, M. and M Jolley, J. (2010). Research design

explained: Instructor’s edition (7th ed.). Wadsworth

Cengage Learning.

Lauesen, S. (1997). Usability engineering in industrial

practice. In Human-Computer Interaction INTER-

ACT’97: IFIP TC13 International Conference on

Human-Computer Interaction, 14th–18th July 1997,

Sydney, Australia, pages 15–22. Springer.

Liew, M. S., Zhang, J., See, J., and Ong, Y. L. (2019).

Usability challenges for health and wellness mo-

bile apps: mixed-methods study among mhealth ex-

perts and consumers. JMIR mHealth and uHealth,

7(1):e12160.

Lizano, F., Sandoval, M. M., Bruun, A., and Stage, J.

(2013). Usability evaluation in a digitally emerg-

ing country: a survey study. In Human-Computer

Interaction–INTERACT 2013: 14th IFIP TC 13 In-

ternational Conference, Cape Town, South Africa,

September 2-6, 2013, Proceedings, Part IV 14, pages

298–305. Springer.

Maqbool, B. and Herold, S. (2021). Challenges in devel-

oping software for the swedish healthcare sector. In

HEALTHINF, pages 175–187.

Maqbool, B. and Herold, S. (2023). Potential effectiveness

and efficiency issues in usability evaluation within

digital health: A systematic literature review. Jour-

nal of Systems and Software, page 111881.

Maramba, I., Chatterjee, A., and Newman, C. (2019). Meth-

ods of usability testing in the development of ehealth

applications: a scoping review. International journal

of medical informatics, 126:95–104.

Matthew-Maich, N., Harris, L., Ploeg, J., Markle-Reid, M.,

Valaitis, R., Ibrahim, S., Gafni, A., Isaacs, S., et al.

(2016). Designing, implementing, and evaluating mo-

bile health technologies for managing chronic condi-

tions in older adults: a scoping review. JMIR mHealth

and uHealth, 4(2):e5127.

A Survey on Usability Evaluation in Digital Health and Potential Efficiency Issues

75

Middleton, B., Bloomrosen, M., Dente, M. A., Hashmat,

B., Koppel, R., Overhage, J. M., Payne, T. H., Rosen-

bloom, S. T., Weaver, C., and Zhang, J. (2013). En-

hancing patient safety and quality of care by improv-

ing the usability of electronic health record systems:

recommendations from amia. Journal of the Ameri-

can Medical Informatics Association, 20(e1):e2–e8.

Morgan, M. A. and Gabriel-Petit, P. (2021). The role

of ux: 2020 benchmark study report and analysis.

https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2021/07/the-

role-of-ux-2020-benchmark-study-report-and-

analysis.php. Accessed: 21-07-2022.

Nalendro, P. A. and Wardani, R. (2020). Application of

context-aware and collaborative mobile learning sys-

tem design model in interactive e-book reader using

design thinking methods. Khazanah Informatika: Ju-

rnal Ilmu Komputer dan Informatika, 6(2).

Namoun, A., Alrehaili, A., and Tufail, A. (2021). A review

of automated website usability evaluation tools: Re-

search issues and challenges. In Design, User Expe-

rience, and Usability: UX Research and Design: 10th

International Conference, DUXU 2021, Held as Part

of the 23rd HCI International Conference, HCII 2021,

Virtual Event, July 24–29, 2021, Proceedings, Part I,

pages 292–311. Springer.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Usability engineering. Morgan Kauf-

mann.

Nugraha, I. and Fatwanto, A. (2021). User experience de-

sign practices in industry (case study from indonesian

information technology companies). Elinvo (Electron-

ics, Informatics, and Vocational Education), 6(1):49–

60.

Ogunyemi, A. A., Lamas, D., Adagunodo, E. R., Loizides,

F., and Da Rosa, I. B. (2016). Theory, practice and

policy: an inquiry into the uptake of hci practices in

the software industry of a developing country. In-

ternational Journal of Human–Computer Interaction,

32(9):665–681.

Paz, F. and Pow-Sang, J. A. (2016). A systematic mapping

review of usability evaluation methods for software

development process. International Journal of Soft-

ware Engineering and Its Applications, 10(1):165–

178.

Rache, A., Lespinet-Najib, V., and Andr

´

e, J.-M. (2014).

Use of usability evaluation methods in france: The

reality in professional practices. In 2014 3rd Interna-

tional Conference on User Science and Engineering

(i-USEr), pages 180–185. IEEE.

Rajanen, M. and Tapani, J. (2018). A survey of game us-

ability practices in north american game companies.

In 27th International Conference on Information Sys-

tems Development (ISD2018). Lund University, Swe-

den.

Ratwani, R. M., Benda, N. C., Hettinger, A. Z., and Fair-

banks, R. J. (2015). Electronic health record vendor

adherence to usability certification requirements and

testing standards. Jama, 314(10):1070–1071.

Rubin, J. and Chisnell, D. (2008). Handbook of usabil-

ity testing: how to plan, design and conduct effective

tests. John Wiley & Sons.

Schmidt, J. D. E. and De Marchi, A. C. B. (2017). Usability

evaluation methods for mobile serious games applied

to health: a systematic review. Universal Access in the

Information Society, 16:921–928.

Solomon, D. H. and Rudin, R. S. (2020). Digital health

technologies: opportunities and challenges in rheuma-

tology. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 16(9):525–

535.

Ventola, C. L. (2014). Mobile devices and apps for health

care professionals: uses and benefits. Pharmacy and

Therapeutics, 39(5):356.

Wright, L. (2020). Usability-testing industry report.

https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2020/08/

user-fountains-2020-usability-testing-industry-report.

php. Accessed: 21-07-2022.

Yanez-Gomez, R., Cascado-Caballero, D., and Sevillano,

J.-L. (2017). Academic methods for usability evalua-

tion of serious games: a systematic review. Multime-

dia Tools and Applications, 76:5755–5784.

Ye, Q., Boren, S. A., Khan, U., and Kim, M. S. (2017).

Evaluation of functionality and usability on diabetes

mobile applications: a systematic literature review.

In Digital Human Modeling. Applications in Health,

Safety, Ergonomics, and Risk Management: Health

and Safety: 8th International Conference, DHM 2017,

Held as Part of HCI International 2017, Vancouver,

BC, Canada, July 9-14, 2017, Proceedings, Part II 8,

pages 108–116. Springer.

Zahra, F., Mohd, H., Hussain, A., and Omar, M.

(2018). Usability dimensions for chronic disease

mobile applications: a systematics literature review.

In Knowledge Management International Conference

(KMICe), pages 363–368. KMICe.

Zapata, B. C., Fern

´

andez-Alem

´

an, J. L., Idri, A., and Toval,

A. (2015). Empirical studies on usability of mhealth

apps: a systematic literature review. Journal of medi-

cal systems, 39(2):1–19.

HEALTHINF 2024 - 17th International Conference on Health Informatics

76