Effects of Virtual-Teacher Appearance and Student Gender on Lesson

Effectiveness in Teaching About Social Issues

Tetsuya Matsui

1 a

and Seiji Yamada

2,3 b

1

Osaka Institute of Technology, Osaka City, Osaka, Japan

2

National Institute of Informatics, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan

3

Graduate Institute for Advanced Studies, SOKENDAI, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan

Keywords:

Human-Agent Interaction, Virtual Agent, Virtual Teacher, Educational Engineering, Pedagogical Agent,

Social Issue.

Abstract:

Virtual teachers (VTs) are an area of focus for the practical application of virtual agents. We focused on a VT

design method for teaching adults about social issues. On the basis of prior research, we hypothesized that a

robot-like VT would be perceived by students as more neutral. To verify this hypothesis, we conducted a two-

factor two-level experiment. One factor was the participants’ gender, and the other was the VTs’ appearance.

We used two types of VTs: human-like and robot-like. In the experiment, these VTs gave a lesson about a

quota system for females. The participants answered a questionnaire on how much they would favor introduc-

ing a quota system after watching a lesson movie presented by a VT. We conducted a two-way ANOVA for

the result of the questionnaire. As a result, female participants were more strongly affected by the robot-like

VT than the human-like VT. We suggest that this needs to be considered when designing VTs that teach about

social issues.

1 INTRODUCTION

In this paper, we examined virtual teachers who teach

about social issues. Virtual teachers (VTs) are virtual

agents that play the role of a teacher. Currently, there

is a worldwide shortage of teachers (Sutcher et al.,

2019). Therefore, the use of robot teachers or VTs

is being considered. Robot teachers are real robots

that are used for education in schools. Experiments

using robot teachers are being conducted with stu-

dents of all ages, from elementary school to univer-

sity (Brink and Wellman, 2020)(Newton and Newton,

2019)(Huang, 2021). In this study, we focused on

“adult education.” Education for adults is important

in promoting lifelong learning and raising awareness

of social issues (Bin Mubayrik, 2020)(Loeng, 2020).

It is important to educate adults as well as minors with

the correct knowledge, especially regarding social is-

sues.

We focused on “neutrality” among the charac-

teristics that robot teachers possess. Edwards et al.

showed that college students felt that robot teachers

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9969-0854

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5907-7382

were neutral in the class (Edwards et al., 2018). The

fact that a robot teacher is perceived as neutral by stu-

dents is a great advantage, especially for robot teach-

ers teaching social issues. Some social issues involve

stakes among multiple groups in society. For exam-

ple, consider the quota system. The quota system al-

locates seats in Congress and other offices on the basis

of gender, human race, and religion (Schwindt-Bayer,

2009). Several European countries have introduced a

quota system in parliament for females, but this is not

yet the case in Japan (Gaunder, 2015). Some males

believe it is not fair to adopt a quota system for fe-

males. When teaching about the quota system, it is

preferable for students to feel that the teacher is neu-

tral. We thought this was where we could use robot

teachers.

VTs are virtual anthropomorphic agents who play

the role of teachers. Many VTs that have been used

in studies have had human-like appearances (Scassel-

lati et al., 2018)(Matsui and Yamada, 2019). VTs

are also called pedagogical agents. In this paper, we

use the term “VTs” to emphasize the role played by

teachers. The appearance of VTs can be configured

in various ways. Prior research has shown that the

appearance of a virtual agent has a significant impact

198

Matsui, T. and Yamada, S.

Effects of Virtual-Teacher Appearance and Student Gender on Lesson Effectiveness in Teaching About Social Issues.

DOI: 10.5220/0012310900003636

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence (ICAART 2024) - Volume 1, pages 198-204

ISBN: 978-989-758-680-4; ISSN: 2184-433X

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

on the user’s internal state. Virtual agents can indi-

cate their gender by their appearance. Several studies

have shown that users have different impressions of

virtual agents depending on the combination of the

virtual agent’s gender and the user’s gender (Payne

et al., 2013)(Guadagno et al., 2007)(Kim et al., 2007).

This indicates that the gender indicated by the virtual

agent’s appearance affects the user’s internal state. A

virtual agent’s appearance can also be human-like.

Banakou et al. showed that embodying a white per-

son in the virtual body (virtual agent avatar) of a black

person can reduce implicit racial prejudice against

blacks (Banakou et al., 2016). Virtual agent attire also

affects users (Fox and Bailenson, 2009). The results

of these previous studies show that the appearance of

a virtual agent has a significant impact on the user.

In this study, we focused on the appearance of VTs.

Matsui and Yamada showed that the combination of

the appearance of VTs and the subjects they teach

changed the effectiveness of the classes taught by the

VTs (Matsui and Yamada, 2019). Matsui showed that

VTs teaching about environmental issues were more

effective in the classroom if they looked more like an-

imals (Matsui, 2021).

In this study, we used two types of VTs: human-

like and robot-like. We expected the robot-like VT to

have the same effect as a real robot. The reason for

this effect is that “students feel that they are neutral”

(Edwards et al., 2018). Robot-like virtual agents are

often used instead of real robots (Bainbridge et al.,

2008)(Kiesler et al., 2008)(Li, 2015). Thus, we hy-

pothesized that a robot-like VT would feel more neu-

tral than a human VT. We envision robot-like VTs

teaching about social issues. Among social issues, we

focused on the quota system. Ultimately, we hypoth-

esized the following.

• H1: Robot-like VTs teaching about the quota sys-

tem are more effective in spreading the adoption

of the quota system than human-like VTs teaching

about the quota system because they feel more fair

to students.

We conducted an experiment to verify this hypoth-

esis. We focused not only on the appearance of the

VTs but also on the gender of the participants. The

reason for this is that there may be differences in atti-

tudes toward the quota system between males and fe-

males, especially the quota system for females. Thus,

we hypothesized the following.

• H2: Female participants are more strongly af-

fected by VTs teaching about the quota system

than male participants.

We conducted the experiment with two factors:

the participants’ gender and VTs’ appearance.

Figure 1: VTs used in experiment.

Table 1: Conditions in experiment.

Condition Participants’ gender VT’s appearance

Condition 1 female human-like

Condition 2 female robot-like

Condition 3 male human-like

Condition 4 male robot-like

2 EXPERIMENT

The experiment was conducted with two factors and

two levels. The factors were the participants’ gender

and the VTs’ appearance. The participants’ gender

had a female level and male level. The VTs’ appear-

ance had a human-like VT level and robot-like VT

level. In the human-like VT level, the VT had a fe-

male human-like appearance. This VT was our orig-

inal Live2D model. In the robot-like VT level, the

VT had a mechanical robot-like appearance. This VT

was a Live2D model that was released by VroidHub

1

.

We chose these VTs to verify our hypotheses formu-

lated in the introduction section. The human-like VT

was a female VT because many studies have used fe-

male virtual agents. Figure 1 shows the VTs used in

the experiment. Table 1 shows all conditions in the

experiment.

The lesson theme in this experiment was “quota

system.” The quota system is a political issue that di-

vides people according to their political beliefs. This

problem has a lot to do with neutrality. Thus, this is

an appropriate theme for this experiment, which seeks

to test the neutrality of robot-like VTs. In this exper-

iment, we will address a quota system for females.

Table 2 shows the utterance text spoken in the lesson.

Next, we will explain the experimental flow. The

experiment was conducted on the web. First, the par-

ticipants watched a movie in which the VT gave a

lesson. In the movie, the VT spoke the lesson text

(shown in Table 2). The movie was about 2 minutes

in length. Figure 2 shows a snapshot of the movie.

After watching the movie, the participants answered

1

https://hub.vroid.com/characters/

7291239036418050595/models/7006001194448814569

Effects of Virtual-Teacher Appearance and Student Gender on Lesson Effectiveness in Teaching About Social Issues

199

Table 2: Speech text in invasive acid rain problem level.

Hello.

Today, I would like to explain the history

and current status of the quota system, which allocates a certain number of people to Congress

and public institutions to ensure the rights of minorities in terms of race, gender, religion, etc.

A “quota system” is a system in which a certain number of seats in Congress,

for example, are always allocated to social minorities.

It is introduced to reflect the opinions of residents with diverse attributes for the sake of a healthy democracy

and to improve the status of those considered to be of low social standing.

The first country in history to introduce a quota system was Norway.

The Norwegian Gender Equality Act of 1978 stipulates that

“when a public committee is established consisting of four or more members,

the members must be selected so that no more than 40 percent of the members are of any one gender.”

This was a revolutionary law at the time,

and it spread first to Scandinavian countries such as Denmark and Sweden and then to the rest of the world.

This is due, in particular, to the increased global awareness of the need to improve the status of females,

especially after World War II and the adoption of the Declaration

on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women by the United Nations.

A measure of the success of this effort is that

the percentage of females in the National Assembly is over 30.

Nordic countries such as Sweden, Denmark, and Norway as well as the Netherlands and Germany

exceed this standard.

In Japan, the percentage of female Diet members is about 10 percent in the House of Representatives

and 20 percent in the House of Councillors, but Japan has not yet adopted a quota system.

However, efforts to increase the percentage of females

in the Diet, as well as in corporate executive positions and university faculties, have been promoted by

successive cabinets.

In April 2023, Prime Minister Kishida announced his intention

to increase the percentage of female executives at TSE prime companies to 30 percent by 2030.

On the other hand, some have expressed the opinion that the quota system discriminates against males

and that “true rights cannot be obtained while being legally singled out for special treatment.”

Another difficult issue being debated is whether this system should be expanded

in the future to include racial and religious minorities other than women.

Figure 2: Snapshot of movie used in experiment.

questionnaires. The questionnaires were constructed

with three questions as follows.

• Q1: Do you favor the introduction of a quota sys-

tem for female legislators?

• Q2: Would you support the introduction of a

quota system for females on the boards of large

corporations and in university faculties?

• Q3: Do you favor the introduction of a quota sys-

tem for religious and racial minorities?

These were questions to examine the effectiveness

of the lesson. The participants answered these three

questions on a 7-point Likert scale (0: not at all, 7:

very much). We analyzed the results of the questions

with a two-way analysis of variance.

All participants were recruited via Yahoo! Crowd-

sourcing

2

and received 50 yen (about 46 cents) as a re-

ward. The reliability of experiments on the web was

2

https://crowdsourcing.yahoo.co.jp/

ICAART 2024 - 16th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

200

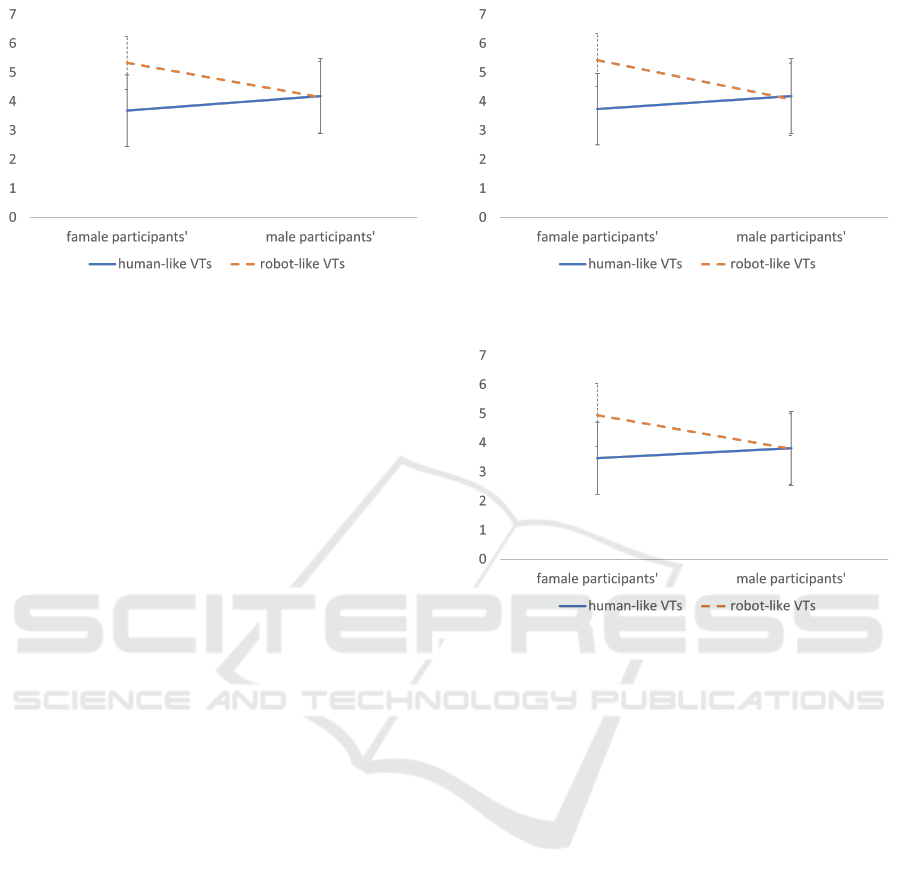

Figure 3: Averages for Q1 in each condition. Error bars

mean SDs.

shown by Crump et al. (Crump et al., 2013). This

experiment was conducted with the approval of the

Ethics Committee at the Osaka Institute of Technol-

ogy.

In condition 1 (female participants, human-like

VT), there were 19 participants, ranging in age from

25 to 50 years for an average of 37.7 (SD = 7.4). In

condition 2 (male participants, human-like VT), there

were 54 participants, ranging in age from 19 to 50

years for an average of 42.5 (SD = 6.4). In condition

3 (female participants, robot-like VT), there were 20

participants, ranging in age from 20 to 78 years for an

average of 48.7 (SD = 14.6). In condition 4 (male par-

ticipants, robot-like VT), there were 81 participants,

ranging in age from 28 to 66 years for an average of

46.7 (SD = 9.4).

3 RESULTS

Table 3 shows the averages and SDs for each question.

We conducted a two-way ANOVA for each ques-

tion.

The top of Table 4 shows the results of the two-

way ANOVA for Q1. There was a statistically signif-

icant interaction between the participants’ gender ×

the VTs’ appearance (p < 0.01). The bottom shows

the results of a simple interaction test for the inter-

actions between the participants’ gender × the VTs’

appearance. There was a significant difference for the

simple main effect for the VTs’ appearance when the

participants’ gender was the female level (p < 0.01).

Also, there was a significant difference for the simple

main effect for the participants’ gender when the VTs’

appearance was the robot-like VT level (p < 0.01).

Figure 3 shows the interaction of Q1.

The top of Table 5 shows the results of the two-

way ANOVA for Q2. There was a statistically signif-

icant interaction between the participants’ gender ×

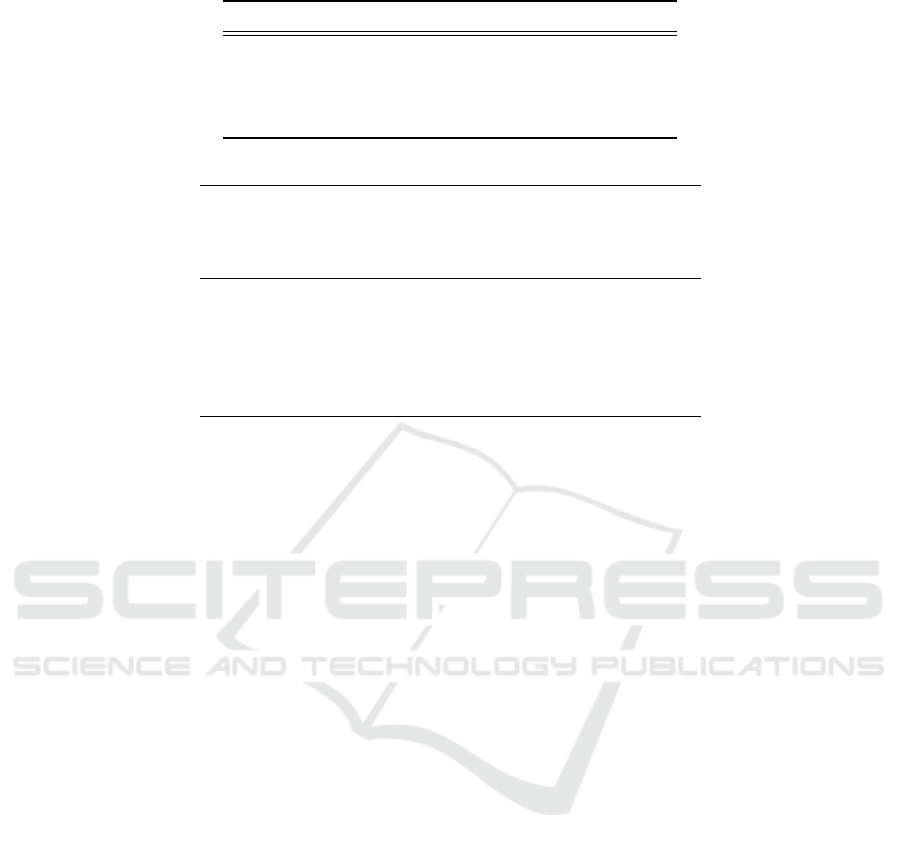

Figure 4: Averages for Q2 in each condition. Error bars

mean SDs.

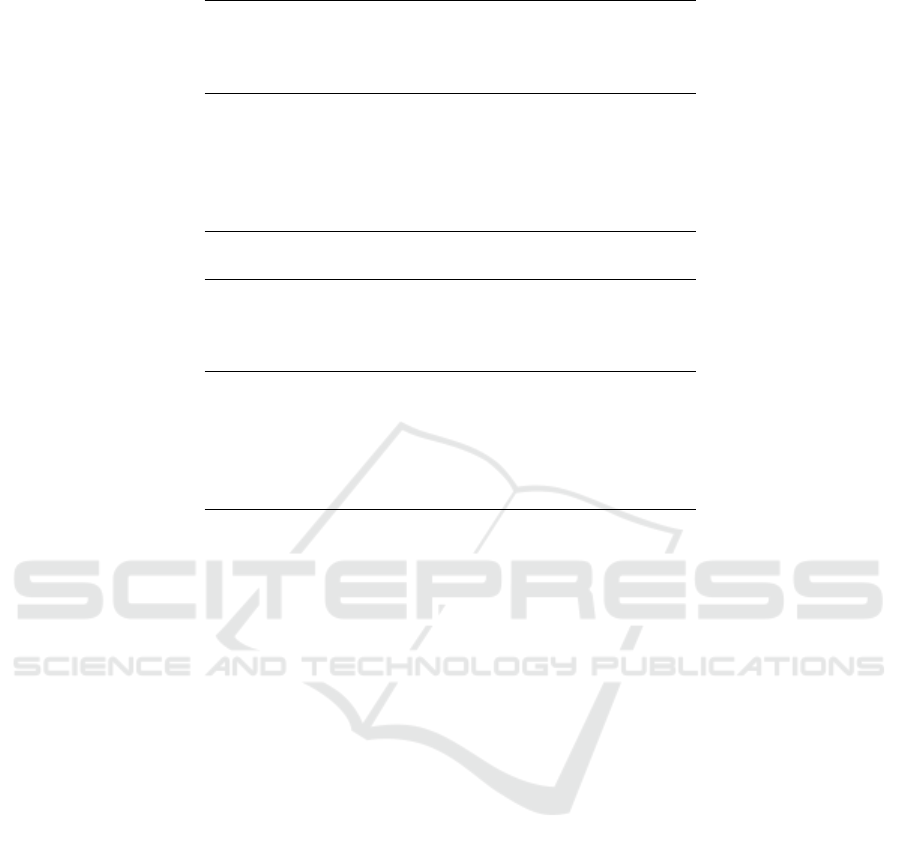

Figure 5: Averages for Q3 in each condition. Error bars

mean SDs.

the VTs’ appearance (p < 0.01). The bottom shows

the results of a simple interaction test for the inter-

actions between the participants’ gender × the VTs’

appearance. There was a significant difference for the

simple main effect for the VTs’ appearance when the

participants’ gender was the female level (p < 0.01).

Also, there was a significant difference for the simple

main effect for the participants’ gender when the VTs’

appearance was the robot-like VT level (p < 0.01).

Figure 4 shows the interaction of Q2.

The top of Table 6 shows the results of the two-

way ANOVA for Q3. There was a statistically signif-

icant interaction between the participants’ gender ×

the VTs’ appearance (p < 0.01). The bottom shows

the results of a simple interaction test for the inter-

actions between the participants’ gender × the VTs’

appearance. There was a significant difference for the

simple main effect for the VTs’ appearance when the

participants’ gender was the female level (p < 0.01).

Also, there was a significant difference for the simple

main effect for the participants’ gender when the VTs’

appearance was the robot-like VT level (p < 0.01).

Figure 5 shows the interaction of Q3.

Effects of Virtual-Teacher Appearance and Student Gender on Lesson Effectiveness in Teaching About Social Issues

201

Table 3: Averages and SDs of scores for each question.

Condition Q1 Q2 Q3

Condition 1 3.68 (1.52) 3.74 (1.52) 3.47 (1.53)

Condition 2 4.19 (1.68) 4.19 (1.67) 3.81 (1.61)

Condition 3 5.33 (0.84) 5.43 (0.85) 4.95 (1.17)

Condition 4 4.15 (1.53) 4.07 (1.55) 3.79 (1.50)

Table 4: Result of ANOVA for scores of Q1. There was significant main effect of interaction.

source F p

participants’ gender 1.43 0.23

VTs’ appearance 8.02 0.00 ∗∗

interaction 9.66 0.00 ∗∗

sub-effect test (simple main effect)

effect F p

participants’ gender (human-like VT) 1.74 0.19

participants’ gender (robot-like VT) 9.72 0.00 ∗∗

VTs’ appearance (female participants) 11.43 0.00 ∗∗

VTs’ appearance (male participants) 0.08 0.77

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Hypothesis Survey

Table 4 and Figure 3 indicate that female partici-

pants were more strongly affected by the VT when

the VT had a robot-like appearance than when it had

a human-like appearance. For male participants, there

was no significant difference between the human-like

VT level and robot-like VT level. To interpret this re-

sult, we must consider the appearance of the VTs. In

the human-like VT level, the VT had a female human-

like appearance. This appearance seemed to make the

participants feel that the VT thinks from a human fe-

male’s perspective. Thus, participants may have felt

the VT had biased opinions when it talked about the

quota system for females. They may have thought

“the VT is acting in her own best interest.” This may

have led to the diminishing influence of the VT. How-

ever, this effect was not observed in the male partic-

ipants. This result suggests that the participants felt

a bias when the VT’s gender was the same as them-

selves. Table 4 and Figure 3 show that the robot-like

VT felt fairer than the human-like VT. This result is

consistent with prior research (Edwards et al., 2018).

Table 5 and Figure 4 also indicate that female par-

ticipants were more strongly affected by the VT when

the VT had a robot-like appearance than when it had

a human-like appearance. This result was the same as

Q1. The result of Q2 shows that the participants had

a tendency to agree with introducing a quota system

to areas other than legislators.

Table 6 and Figure 5 also indicate that female par-

ticipants were more strongly affected by the VT when

the VT had a robot-like appearance than when it had

a human-like appearance. This result was the same as

Q1. This is a remarkable result. Q3 was not directly

related to “female.” Thus, the bias derived from the

VTs’ appearance may not have affected this question.

We have to wonder why there was a significant differ-

ence for this question. One possible explanation is the

effect of the previous question. Participants who an-

swered Q1 and Q2 with higher scores may have also

given higher scores to Q3. In any case, the results sug-

gest that the robot-like VT was effective in persuading

the participants to adopt a quota system for minorities

other than females.

4.2 Design Policy from Experimental

Results

These results support our hypothesis. The results of

the three questions show that the robot-like VT was

effective in persuading the female participants to ac-

cept the quota system. This suggested that the fe-

male participants may have felt that the robot-like

VT was neutral. The female participants seemed to

think that the robot-like VT spoke without regard to

its own interests. Otherwise, the female human-like

VT seemed to be perceived as speaking for her own

benefit. This may have led to differences in the results

between conditions. However, this difference was not

observed for the male participants, who seemed to

think that the human-like VT was as fair as the robot-

ICAART 2024 - 16th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

202

Table 5: Result of ANOVA for scores of Q2. There was significant main effect of interaction.

source F p

participants’ gender 2.02 0.16

VTs’ appearance 6.79 0.01 ∗

interaction 8.66 0.00 ∗∗

sub-effect test (simple main effect)

effect F p

participants’ gender (human-like VT) 1.10 0.30

participants’ gender (robot-like VT) 9.99 0.00 ∗∗

VTs’ appearance (female participants) 9.97 0.00 ∗∗

VTs’ appearance (male participants) 0.12 0.73

Table 6: Result of ANOVA for scores of Q3. There was significant main effect of interaction.

source F p

participants’ gender 2.23 0.14

VTs’ appearance 6.95 0.00 ∗∗

interaction 7.36 0.00 ∗∗

sub-effect test (simple main effect)

effect F p

participants’ gender (human-like VT) 0.69 0.41

participants’ gender (robot-like VT) 9.69 0.00 ∗∗

VTs’ appearance (female participants) 9.38 0.00 ∗∗

VTs’ appearance (male participants) 0.00 0.94

like VT.

4.3 Limitation

The greatest weakness of this study is that it did

not examine male human-like VTs. Male human-

like VTs may affect only male participants. Alter-

natively, male human-like VTs may be perceived just

like robot-like VTs because males do not benefit di-

rectly from the quota system. This is our future work.

5 CONCLUSION

In this paper, we discussed the design of VTs for

teaching adults about social issues. On the basis of

prior research, we hypothesized that robot-like VTs

would be perceived by students as more neutral. To

verify this hypothesis, we conducted a two-factor

two-level experiment. One factor was the partici-

pants’ gender, and the other was the VTs’ appear-

ance. We used two types of VTs: human-like and

robot-like. In the experiment, these VTs gave a les-

son about the quota system for females. The partici-

pants answered a questionnaire about how much they

favored introducing a quota system after watching the

lesson movie. We conducted a two-way ANOVA for

the result of the questionnaire. As a result, female

participants were more strongly affected by the VT

when the VT had a robot-like appearance than when

it had a human-like appearance. This result seemed

to occur from a bias brought about by the VT’s ap-

pearance. The female participants probably felt that

the female human-like VT spoke in its own best inter-

est and the robot-like VT spoke neutrally. This result

shows that VTs’ appearance has a huge impact on stu-

dents when they teach about social issues. We suggest

that this needs to be considered when designing VTs

that teach about social issues.

REFERENCES

Bainbridge, W. A., Hart, J., Kim, E. S., and Scas-

sellati, B. (2008). The effect of presence on

human-robot interaction. In RO-MAN 2008-The

17th IEEE International Symposium on Robot

and Human Interactive Communication, pages

701–706.

Banakou, D., Hanumanthu, P. D., and Slater, M.

(2016). Virtual embodiment of white people in a

black virtual body leads to a sustained reduction

in their implicit racial bias. Frontiers in human

neuroscience, page 601.

Bin Mubayrik, H. F. (2020). New trends in formative-

summative evaluations for adult education. Sage

Open, 10(3):2158244020941006.

Brink, K. A. and Wellman, H. M. (2020). Robot

Effects of Virtual-Teacher Appearance and Student Gender on Lesson Effectiveness in Teaching About Social Issues

203

teachers for children? young children trust

robots depending on their perceived accu-

racy and agency. Developmental Psychology,

56(7):1268.

Crump, M. J., McDonnell, J. V., and Gureckis, T. M.

(2013). Evaluating amazon’s mechanical turk as

a tool for experimental behavioral research. PloS

one, 8(3):e57410.

Edwards, B. I., Muniru, I. O., Khougali, N., Cheok,

A. D., and Prada, R. (2018). A physically em-

bodied robot teacher (pert) as a facilitator for

peer learning. In 2018 IEEE frontiers in edu-

cation conference (FIE), pages 1–9.

Fox, J. and Bailenson, J. N. (2009). Virtual virgins

and vamps: The effects of exposure to female

characters’ sexualized appearance and gaze in

an immersive virtual environment. Sex roles,

61:147–157.

Gaunder, A. (2015). Quota nonadoption in japan: the

role of the women’s movement and the opposi-

tion. Politics & Gender, 11(1):176–186.

Guadagno, R. E., Blascovich, J., Bailenson, J. N., and

McCall, C. (2007). Virtual humans and persua-

sion: The effects of agency and behavioral real-

ism. Media Psychology, 10(1):1–22.

Huang, S. (2021). Design and development of edu-

cational robot teaching resources using artificial

intelligence technology. International Journal of

Emerging Technologies in Learning, 15(5).

Kiesler, S., Powers, A., Fussell, S. R., and Torrey,

C. (2008). Anthropomorphic interactions with

a robot and robot–like agent. Social cognition,

26(2):169–181.

Kim, Y., Baylor, A. L., and Shen, E. (2007). Pedagog-

ical agents as learning companions: the impact

of agent emotion and gender. Journal of Com-

puter Assisted Learning, 23(3):220–234.

Li, J. (2015). The benefit of being physically

present: A survey of experimental works com-

paring copresent robots, telepresent robots and

virtual agents. International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, 77:23–37.

Loeng, S. (2020). Self-directed learning: A core con-

cept in adult education. Education Research In-

ternational, 2020:1–12.

Matsui, T. (2021). Power of gijinka: Designing vir-

tual teachers for ecosystem conservation educa-

tion. In Proceedings of the 9th International

Conference on Human-Agent Interaction, pages

328–331.

Matsui, T. and Yamada, S. (2019). The design method

of the virtual teacher. In Proceedings of the 7th

International Conference on Human-Agent In-

teraction, pages 97–101.

Newton, D. P. and Newton, L. D. (2019). Humanoid

robots as teachers and a proposed code of prac-

tice. In Frontiers in education, volume 4, page

125.

Payne, J., Szymkowiak, A., Robertson, P., and John-

son, G. (2013). Gendering the machine: Pre-

ferred virtual assistant gender and realism in

self-service. In Intelligent Virtual Agents: 13th

International Conference, IVA 2013, Edinburgh,

UK, August 29-31, 2013. Proceedings 13, pages

106–115.

Scassellati, B., Brawer, J., Tsui, K., Nasihati Gi-

lani, S., Malzkuhn, M., Manini, B., Stone, A.,

Kartheiser, G., Merla, A., Shapiro, A., et al.

(2018). Teaching language to deaf infants with

a robot and a virtual human. In Proceedings of

the 2018 CHI Conference on human Factors in

computing systems, pages 1–13.

Schwindt-Bayer, L. A. (2009). Making quotas work:

The effect of gender quota laws on the election of

women. Legislative studies quarterly, 34(1):5–

28.

Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., and Carver-

Thomas, D. (2019). Understanding teacher

shortages: An analysis of teacher supply and de-

mand in the united states. Education policy anal-

ysis archives, 27(35).

ICAART 2024 - 16th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence

204