H

ˆ

osea: A Touch Table for Cognitive and Motor Rehabilitation

for the Elderly - A Preliminary Study

Maxime Mac

´

e

1,2,3

, Lise Mac

´

e

5

, Emmanuelle M

´

en

´

etrier

4

, Paul Richard

3

and Tassadit Amghar

2

1

KARA Technology, Saint-Barth

´

elemy-d’Anjou, France

2

LERIA SFR Mathstic, University of Angers, 2 Bd. Lavoisier, Angers, France

3

LARIS SFR Mathstic, University of Angers, 62 Av. Notre-Dame du Lac, Angers, France

4

LPPL SFR Confluence, University of Angers, 2 Bd. Lavoisier, Angers, France

5

Department of Psychology, University of Nantes, Nantes, France

Keywords:

Touch Table, Elderly, Cognitive Decline, Rehabilitation, Usability.

Abstract:

As the population ages, it is becoming increasingly important to offer technological solutions for cognitive-

motor rehabilitation. In this context, we have designed H

ˆ

osea, a new touch table offering an attractive, ac-

cessible and stimulating interface for the elderly. The table integrates various motor and cognitive exercises.

The study presented in this article examines the ease of use of the table, as well as the motivation and effort

perceived by elderly people. To achieve this, we engaged with 43 elderly individuals in good health, present-

ing them with a 15-minute session involving three games accessible on the table. At the end of the session,

participants were administered standardized scales, evaluating the usability of the table via the F-SUS, the

degree of perceived effort with the NASA-TLX, and their motivation with the SIMS. The results suggest that

the H

ˆ

osea touch table offers a user-friendly and motivating environment. These results motivate further work

on a personalized rehabilitation program.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digital technologies for seniors require special at-

tention. Among the specificities of elderly users,

we find diminished muscular conditions and cogni-

tive decline (Awan, 2021). Therefore, gerontech-

nology must take into account the evolution of mo-

tor skills, visual and hearing disorders, but also cog-

nitive decline (Liao, 2018). The intensity of age-

related losses varies among individuals, affecting dis-

tinct cognitive functions and manifesting themselves

at different stages, thereby influencing various aspects

of daily life activities. In this case, innovative tech-

nologies can be used to stimulate motor and cogni-

tive skills (Lee, 2021). Older people may encounter

several difficulties with everyday digital interfaces for

reasons related to learning barriers and accessibil-

ity issues (Iancu, 2020; Awan, 2021). A main rea-

son is that interfaces generally require robust motor

skills and specific cognitive abilities such as work-

ing memory, short-term memory, and selective atten-

tion (Iancu, 2020; Liao, 2018). The lack of digital

accessibility for older people has more to do with

non-inclusive design than a lack of capacity (Iancu,

2020; Lee, 2021). The complexity of design, its rich-

ness and its standards not transmitted to a population

less aware of new technologies makes design a ma-

jor element of digital accessibility (Tajudeen, 2022).

The same observation applies in the context of video

games, where the specificity of the environment in

terms of game design and game dynamics must also

be taken into account for accessibility (Ijsselsteijn,

2007).

Faced with this, a global approach is recom-

mended to develop interfaces for older people with

simpler interactions and better retention of informa-

tion alongside adequate support. This study evaluates

the usability, perceived workload and motivation for

using a new touch table called H

ˆ

osea and its software

dedicated to seniors by offering exercises that stimu-

late cognition and physical effort. To do so, the fol-

lowing section discusses related work on touch tables

for the elderly. Section 3 details the conducted ex-

periment, while Section 4 outlines the experiment’s

results. Section 5 presents a discussion and analysis

of the results. The paper ends by a conclusion and

provides some tracks for future work.

Macé, M., Macé, L., Ménétrier, E., Richard, P. and Amghar, T.

Hôsea: A Touch Table for Cognitive and Motor Rehabilitation for the Elderly - A Preliminary Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0012304000003660

In Proceedings of the 19th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2024) - Volume 1: GRAPP, HUCAPP

and IVAPP, pages 419-426

ISBN: 978-989-758-679-8; ISSN: 2184-4321

Copyright © 2024 by Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

419

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Touch Table Interface

A touch table refers to a horizontal 2D platform for

digital content and tactile interactions, with two main

types distinguished by technological differences (Dil-

lenbourg, 2011). Projection tables use a flat surface

with an integrated frame mechanism (Figure 1-a) or a

rear projection (Figure 1-b). The main issues with this

approach include user shadow interference and low

projected image resolution (Geller, 2006). However,

projection systems allow the use of physical object

and the ability to display the screen on any flat surface

(Dillenbourg, 2011). Among examples of table by

projection, the DiamondTouch table from Mitsubishi

is well-known (Chen, 2012) as well as the SMART ta-

ble by SMART Tech (Dillenbourg, 2011). The second

touch table system incorporates a large touchscreen

(Figure 1-c) either within or on top of a dial such as

Microsoft’s PixelSense (Kubicki, 2015). The screens

use several different technologies to capture user’s in-

teractions, generally based on electrical projected ca-

pacitive multitouch. However, there are other meth-

ods such as infrared LEDs and photodiodes (Loenen,

2007). Interactive tables take advantage of natural di-

rect touch and not using proxies such as mouse or

joystick controllers to interact (Annett, 2012). Thus,

it requires low cognitive demand from users (Shen,

2006) and enables integration for populations with

intellectual and/or motor disabilities (Annett, 2012;

Chen, 2012). In addition, touch tables bring new ad-

ditional interactions (

¨

Oring, 2019) which stimulates

the creation of new contents, with a strong emphasis

on audio and visual feedback (Mahmud, 2008; Dillen-

bourg, 2011). Some studies have explored the use of

touch tables for the elderly. The HERMES project in-

troduced a touch table designed for cognitive training

by employing an approach limiting the appearance of

errors to facilitate learning, called errorless (Buiza,

2009). Additionally, the Eldergames project focused

on cognitive stimulation through games aimed at im-

proving selective attention, concentration and control

(Gamberini, 2009). In terms of mental rehabilita-

tion, the SOCIABLE and E-Core programs also offer

activities to support and rehabilitate cognitive skills

(Jung, 2013; Danassi, 2014). Other studies have also

been carried out, notably during the interactive table

golden age, around 2010s (Annett, 2009; Mahmud,

2008). However, the literature on touch tables re-

mains very limited and, as Bruun et al. mentioned,

focuses mainly on software development and inter-

action techniques and less on usability studies and

user performance (Bruun, 2016). This is also true for

Figure 1: The three main types of tactile table.

touch tables for the elderly, despite new developments

in current research (Cerezo, 2020; Hyry, 2017).

2.2 H

ˆ

osea Touch Table

Developed by KARA Technology, H

ˆ

osea is a touch

table initially conceived for occupational therapy. The

touch table aims to enhance collaboration and interac-

tion between patients and healthcare professionals. It

allows solo or collaborative activities and is specifi-

cally designed to be a touch table accessible to people

with reduced mobility. Unlike other touch tables, its

height can be adjusted using bolts to accommodate

wheelchair users or those who prefer to stand. The

screen can be positioned flat (0° tilt) or tilted (up to

85°). The table offers better movement with four bidi-

rectional wheels with brakes. The 43-inch screen of

the H

ˆ

osea table allows bi-manual interaction with a

maximum of ten contact points. A presentation of the

table is provided in Figure 2. To meet the demand for

accessible content, we collaborated with two teams of

occupational therapists from two different centers to

create a dedicated app integrated on the H

ˆ

osea table.

The software was co-designed using regular feedback

in the form of periodic requests from the two part-

ner centers. The software is based on Laravel, a PHP

framework and a MYSQL database. Patient data is

encrypted and stored in a local database. The first

version included 17 games related to nine work cat-

egories defined with occupational therapists: visual-

spatial ability, causal effect, hand-eye coordination,

musculoskeletal amplitude, memory, balance, strat-

egy, precision and processing speed. Depending on

the game, different session data are recorded (e.g.,

heatmap, score, time, number of trials). Customiz-

ing various aspects of the game to individual users is

beneficial, but is not common in commercial games.

We worked closely with the occupational therapists

to customize each game, starting from open-source

projects or developing from scratch, and considering

factors like screen size, object speed, target score,

and the number of trials based on their experience

with commercial games. The settings are stored in

a database to adjust difficulty and keep the same set-

HUCAPP 2024 - 8th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

420

Figure 2: 3D presentation of the H

ˆ

osea touch table.

tings for future sessions. The objective of this study

was to evaluate the acceptability of the H

ˆ

osea table by

elderly people in terms of usability, perceived effort

and motivation to follow a cognitive training program

on this interface. For this, we met 43 individuals aged

55 to 85, whom we asked to play three of the tasks

implemented on the table: the Simon Says, the flow

free and the wordfind games (See, Section 3, for more

details). In this study, we did not use the game adjust-

ment functionality to guarantee the same task charac-

teristics for each participant. Different questions were

asked at the end of each game and an overall evalua-

tion of the interface was offered at the end of the ses-

sion. We expected that the interface would be well

received by the participants, with high scores on the

F-SUS (usability scale, (Gronier, 2021)), the SIMS

(motivation scale, (Guay, 2000)), and low scores on

the NASA-TLX (scale evaluating the perceived load,

(Hart, 1988; Maincent, 2001)).

3 EXPERIMENTAL STUDY

3.1 Participants

The group of participants was comprised of 43 vol-

unteers (65.12% women), French-native or bilingual

speakers between the ages of 55 and 85. The aver-

age age was 68.74 (SD = 7.10). The sample may ap-

pear heterogeneous, but this choice was motivated by

the subsequent phases of development of the H

ˆ

osea

software, including the development of an algorithm

aimed at automatic personalization and adaptation of

the exercises offered. The diversity of profiles en-

countered was motivated to allow higher sensitivity

of the algorithm. The average education duration was

16.63 years (SD = 3.88) while the average profes-

sional life of the participants was 31.35 years (SD =

11.88), as shown in Table 1. The participants are all

healthy volunteers who accepted to participate in the

study following an online call, or through local com-

Table 1: Demographic characteristics and psychological as-

sessment. Standard deviations are presented between brack-

ets.

Baseline characteristics Elderly (N = 43)

Mean age 68.74 (7.10)

Sex (% women) 65.11

Laterality (% right) 95.34

Mean education level

(years)

16.63 (3.88)

Mean years of work

(years)

31.35 (11.88)

Psychological testing

MMSE (/30) 26.51 (2.59)

mini-GDS (/4) 0.36 (0.76)

munication. To meet ethical questions, each partici-

pant signed informed consent before the study and all

data were anonymized.

3.2 Procedure

The study was conducted in two stages: participants

firstly used the table, as displayed in figure 3, be-

fore filling out questionnaires. Before the session,

participants completed a health questionnaire that in-

cluded self-assessment of fine motor skills and vi-

sion/hearing abilities. Participants were also adminis-

tered the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) (Folstein,

1975) and the Mini Geriatric Depression Scale (Mini-

GDS) (Cl

´

ement, 1997), to ensure the absence of cog-

nitive disorder or depressive state likely to affect re-

sults. Participants were also asked about their comfort

level with digital tools. After the basic questionnaires,

there was a 15-minute touch table test session, dur-

ing which participants performed three H

ˆ

osea soft-

ware tasks. Tasks were randomly shown for 5 minutes

each, and were followed immediately by usability

questions addressed orally by the experimenter. After

each game, participants were also asked about sev-

eral aspects: familiarity with a similar version of the

game, adequacy of object size, questions about men-

tal, physical, and performance load (from the NASA-

TLX), and a general open-ended question allowing

feedback on the game. Once the 15-minute gaming

session was over, the participants completed with the

experimenter standardized scales aimed at assessing

the usability of the table with the F-SUS (Brooke,

1995; Gronier, 2021), subjective workload with the

NASA-TLX (Hart, 1988; Maincent, 2001), as well as

Hôsea: A Touch Table for Cognitive and Motor Rehabilitation for the Elderly - A Preliminary Study

421

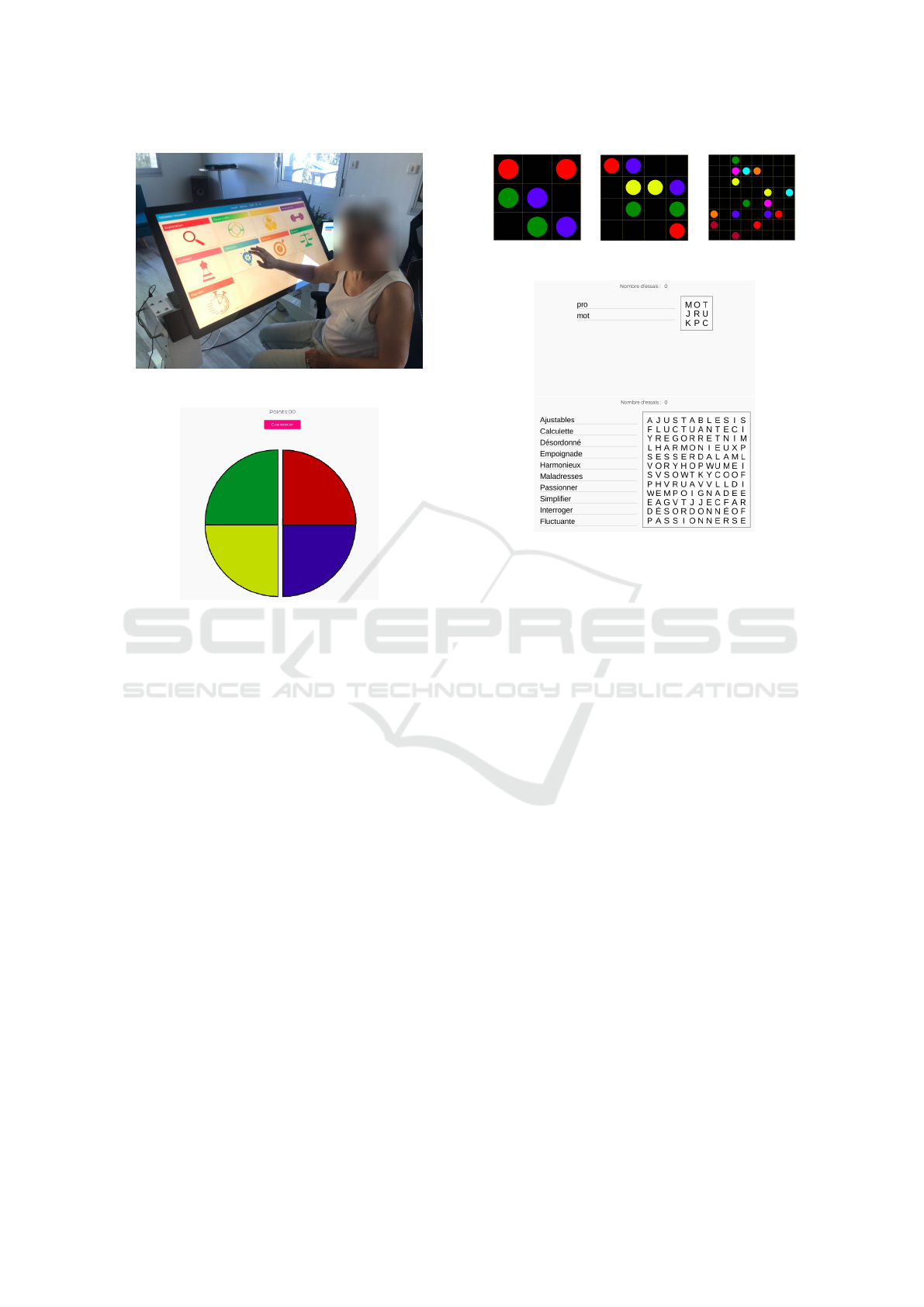

Figure 3: Supervised usability study with a coordinator.

Figure 4: Adapted version of Simon Says game.

their motivation to use the table with the SIMS (Guay,

2000).

3.3 Tasks

3.3.1 Simon Says

One of the three tasks from the H

ˆ

osea software’s used

during the study was an adapted version of the Si-

mon Says game. The task aims to reproduce color

sequences using a point touch in the indicated areas.

Success leading to the game introducing longer se-

quences (i.e., introducing a new color in the last se-

quence). The color sequence remains constant, with

each color displayed one second apart, as shown in

Figure 4. The game is configured to offer a single

sound for each color.

When the participant fails to reproduce the se-

quence, the game ends. If a participant completed a

game session before the five-minute limit, a new game

with the same color sequence was restarted by the ex-

perimenter.

3.3.2 Flow Free

The second game selected was an adapted version of

the Flow Free, visible in Figure 5. The task is to con-

Figure 5: Three grids from the adapted Flow Free game.

Figure 6: Two grids from the adapted Wordfind game.

nect pairs of dots of the same color by sliding a fin-

ger across them to fill the grid without crossing each

other. The difficulty of the task gradually increases

with the size of the grids and the number of pairs to

connect. Thus, the first three grids (3:3 matrix) re-

quired the connection of 3 pairs; then 4 pairs in the

next three ones (matrix 4:4), and this until 7 pairs

(grid 7:7). After completing a grid, the participant

moved on to the next one with the help of the experi-

menter.

3.3.3 Wordfind Dame

Lastly, we proposed a digital version of the Wordfind

game, assuming it would be more recognizable to the

intended age group (Figure 6). Similar to the Flow

Free, the difficulty of the game increased as partici-

pants filled in the grids, underlining the words with

their finger: each level had larger grids with more

words. The word list on the left matched and high-

lighted words in the grid as they were found. All grids

allowed words to be arranged horizontally or verti-

cally and could have appeared in any direction (e.g.,

right to left).

3.4 Collected Data

Once the 15-minute gaming session was over, the

participants completed, with the help of the experi-

menter, standardized scales presented in a fixed order.

The first scale administered was the F-SUS (French

HUCAPP 2024 - 8th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

422

System Usability Scale) (Brooke, 1995; Gronier,

2021), consisting of 10 questions assessing interface

usability using a 5-points Likert scale, with the value

1 refering to “Strongly disagree” and 5 to “Strongly

agree”. The scale gives a usability score from 0 to

100, reflecting the user-friendliness of the system.

Researchers generally consider an SUS score between

70 and 100 to be an acceptable range. Below this

score, the interface is considered marginally accept-

able for the target population (Bangor, 2008).

The second scale proposed was the NASA-TLX

(Hart, 1988; Maincent, 2001), aimed at assessing sub-

jective workload after a physical or cognitive activity

on six dimensions evaluated by different subscales.

These subscales require rating feelings from 1 to 20

for Mental demand, Physical demand, Time demand,

Performance, Effort, and Frustration. The last mea-

surement realized was the SIMS (Situational Intrinsic

Motivation Scale) (Guay, 2000) to assess participants’

motivation for the tasks. More specifically, the SIMS

assesses whether a session was perceived as stimu-

lating, interesting, and personally rewarding through

four subscales, and involves answering questions us-

ing a Likert scale. While the SIMS is usually adminis-

tered on a 7-points scale, we used a 8-points one (with

1 for “Strongly disagree” and 8 for “Strongly agree”).

This prevents participants to refer to a cut-off value.

The first subscale, Intrinsic motivation, assesses

autonomous motivation. The second one, Internal

Regulation, assesses motivation driven by personal

values, beliefs, or goals. External regulation mea-

sures motivation influenced by external rewards. Fi-

nally, the Amotivation subscale evaluates overall lack

of motivation.

Four extra questions followed the survey, address-

ing post-session feelings. These included an open

question about participants’ post-study emotions and

three questions about their experience with the table.

Using a 10-points scale, where 1 meant ”really bad”

and 10 ”very good”, participants were asked to rate

the interface quality, touchscreen suitability for their

condition, and their ability to use it independently.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Baseline Characteristics

We collected psychological health data using the

MMSE and mini-GDS. Regarding the MMSE, the re-

sults indicated that 55.81% participants had a score

suggesting the absence of cognitive disorder (27-30),

30.23% presented a mild score (24-26) presenting

normal cognition with some points of vigilance, and

13.95% had a score between 18 and 23 with sus-

pected mild cognitive impairment (Derouesne, 1999).

In terms of psychiatric disorders, 23.25% of partici-

pants presented suggestive signs of depression (mini-

GDS score > 0) (Cl

´

ement, 1997). Regarding digi-

tal habits, participants evaluated their skills at a mean

level of 6.49 after reporting their response on a scale

from 1 to 10, and primarily engaged in basic activi-

ties like communication, research, and information-

seeking. In addition, 23.25% participants declared

playing regularly video games. Concerning the fre-

quency of use of digital tools, most people (86.05%)

reported using a numerical device on a daily basis.

Apart from that, 4.65% individuals mentioned weekly

use, and 2.33% used them monthly. Finally, it seems

worth mentioning that 11.63% have worked in infor-

mation technologies during their careers.

The results in this section are computed from data

from all participants for the sake of inclusiveness of

H

ˆ

osea, and account for variations in physical, cogni-

tive, and psychiatric abilities within the aging popula-

tion intended for using the touch table.

4.2 Usability Study

According to F-SUS, the mean usability score was

91.33/100, suggesting a high acceptability of the ta-

ble (Bangor, 2008). Based on the 10 SUS questions,

8 of them presented a standard deviation of less than

1.00, indicating homogeneous evaluations. The ques-

tion with a higher standard deviation concerned sup-

port in use (mean = 1.98; SD = 1.42) suggesting the

need of a supervisor. We also assessed the subjec-

tive workload of users after using the table. Figure

7 presents the average perceived demand of our par-

ticipants based on the 6 NASA-TLX subscales. Af-

ter scaling to 100 the results of each subscale inde-

pendently, Mental demand on the touch table seems

moderate, with a mean height of 64.77 (SD = 20.79).

The mean levels of Physical (M = 22.44, SD = 18.69)

and Temporal demands (M= 29.42,SD = 23.56) dur-

ing the execution of activities were reported as low

by participants. Moreover, the Effort required was

moderate with a mean score of 52.44 (SD = 27.50).

Participants also reported high auto-evaluated Perfor-

mance on the proposed tasks with a mean score of

78.49 (SD = 12.84), but manifested a strong level of

Frustration during the tabletop sessions, with a mean

score of 86.51 (SD = 9.03). Finally, the mean scores

obtained at the SIMS subscales are depicted in Figure

8. The mean score of 7.26 (SD = 1.19) on Intrinsic

motivation suggests a relatively good motivation dur-

ing the sessions. The score on Internal regulation was

also high, with an average score of 6.85 (SD = 1.53).

Hôsea: A Touch Table for Cognitive and Motor Rehabilitation for the Elderly - A Preliminary Study

423

Figure 7: NASA-TLX observed for the six subscales.

Figure 8: SIMS observed for the four subscales.

Consistently, the External regulation and the Amoti-

vation mean scores were low, with 3.05 (SD = 1.76),

and 2.23 (SD = 1.12), respectively. Other questions

were asked to assess the quality of the table. On aver-

age, the interface was considered to be of high quality,

with a mean score of 87.85/100 (SD = 7.74). Sim-

ilarly, a mean score of 86.78/100 (SD = 14.22) was

given for the ability to use the table independently.

Finally, the participants found that the table was suit-

able for their use up to 87.73/100 (SD = 12.98).

4.3 Analysis by Sub-Groups

As the conditions for applying an ANOVA were not

met, due to unbalanced groups and insufficient num-

bers in some of them (n = 24 in the group with

higher MMSE scores [27-30]); n = 13 for moderate

scores [24-26], and n = 6 for lower MMSE scores

[18-23]), we conducted a Kruskal-Wallis test to deter-

mine the impact of cognitive efficiency (operational-

ized through our 3 MMSE groups) on usability testing

results. The analysis revealed no statistically signifi-

cant differences in overall F-SUS, NASA-TLX, and

SIMS mean scores (all ps > .05). Moreover, we per-

formed a Mann-Whitney test to examine whether the

presence of a depression indicator (score > 0 from the

mini-GDS) had an impact on usability testing results.

The analysis indicated no statistically significant vari-

ation in overall usability scores (all ps > .05). Finally,

we performed a Mann-Whitney test to assess whether

perceived visual and auditory dysfunctions had an ef-

fect on system usability. These results indicated no

significant variation in perceived usability related to

visual and auditory abilities (all ps > .05).

5 DISCUSSION

Our study aimed to evaluate the usability of the H

ˆ

osea

table for seniors. Results of the F-SUS (Brooke,

1995; Gronier, 2021) suggests that the interface is

well received by a large panel of healthy seniors.

Compared to similar studies, the SUS score is higher

(Elboim-Gabyzon, 2021). The touch table and the

design of the proposed games seem to have an im-

pact on the acceptability of the interface. Results ob-

tained with the NASA-TLX showed that using the

touch table requires continuous mental effort due to

the complexity of the proposed tasks. The diver-

gence in terms of Mental demand may be linked to

the heterogeneity of the study population and is con-

sistent with similar results on other cognitive training

on touch screens (Lu, 2017). There is also a mini-

mal perceived Physical demand similar to results pre-

sented in studies on tablets, suggesting that the size

of the table’s touch screen is not a factor increasing

physical demand (Castilla, 2020; Lu, 2017). Partici-

pants also reported low Temporal demand, suggesting

that the pace of the tasks was adapted to their abili-

ties. The Frustration subscale mean score was high,

a result that can be attributed to the time constraints

of the protocol, as expressed several times by partic-

ipants in the feedback question following each game.

On average, the NASA-TLX subscales showed little

variation across participants. Further analyses exam-

ined the effects of MMSE and mini-GDS scores and

reported no effect of theses variables on the different

dimensions assessed by this scale. However, null re-

sults must always be considered with caution. In our

case it is possible that its observations were caused

by the low number of participants in some groups and

the imbalance of numbers between the groups. On av-

erage, participants reported being motivated for rea-

sons related to curiosity, enjoyment or skills acquired

as highlighted by scores reported in the SIMS Intrin-

sic motivation and Internal regulation scales. Internal

regulation was the subscale with a high score, sug-

gesting pleasure and satisfaction in carrying out the

exercises. Conversely, External motivation and Amo-

tivation mean scores were low, suggesting that exter-

nal factors did not influence as much motivation and

that general motivation was preserved throughout the

study. As reported by participants, the enjoyable and

user-friendly large screen added extra motivation for

HUCAPP 2024 - 8th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

424

the provided exercises. Moreover, our results sug-

gest that there was no difference in the evaluation

of usability, perceived demand and motivation as a

function of cognitive level, depression and visual and

auditory abilities. However, there are limitations to

these results. First, the participants were independent

individuals with good experience with digital tools.

In addition, the seniors in the study are mostly ac-

tive, which limits the conclusions for sedentary or re-

tired profiles. In addition, the limited number of par-

ticipants may not cover all senior cognitive profiles,

reflecting the great diversity of their conditions and

characteristics, as noted previously. We deliberately

shortened the exposure time at the table and focused

on participants who were experiencing the interface

for the first time; a more in-depth study on more reg-

ular use could provide more information, particularly

on long-term perseverance. Another limitation relies

on the fact that the activities provided were not de-

signed with a user-centric approach tailored explicitly

for the elderly population.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

H

ˆ

osea appears as a user-friendly interface, aligning

with prior research on digital content integration on

regular touchscreen (Ten Brinke, 2017; Groenewoud,

2017) offering an accessible and engaging fun envi-

ronment requiring moderate physical and cognitive

abilities among seniors. Future work will analyze

the quantitative data recorded by the table and study

their use in the context of machine learning to deduce

needs for adapting exercises according to the user pro-

file. We will study the use of Bayesian optimization

models to define an ideal configuration for each exer-

cise and respond to multi-objective optimization be-

tween rehabilitation effort and exercise accessibility.)

REFERENCES

Annett, Anderson, B. (2012). User perspectives on multi-

touch tabletop therapy.

Annett, Anderson, G. H. (2009). Using a multi-touch table-

top for upper extremity motor rehabilitation. Proceed-

ings of the 21st Australasian Computer-Human Inter-

action Conference, OZCHI 2009.

Awan, Mujtaba & Ali, S. . A. M.-F. A. M. U. H. K. D.

(2021). Usability barriers for elderly users in smart-

phone app usage: An analytical hierarchical process-

based prioritization. Scientific Programming, pages

1–14.

Bangor, Aaron, K. P. T. P. M. T.-J. (2008). The system

usability scale (sus): an empirical evaluation. In-

ternational Journal of Human-Computer Interaction,

24:574–.

Brooke, J. (1995). Sus: A quick and dirty usability scale.

Usability Eval. Ind, 189.

Bruun, Jensen, K. K. (2016). Escaping the trough: Towards

real-world impact of tabletop research. International

Journal of Human–Computer Interaction.

Buiza, Soldatos, P. G. E. T. (2009). Hermes: Pervasive com-

puting and cognitive training for ageing well.

Castilla, Diana, S.-R. C. Z. I. G.-P. A. B. C. (2020). Design-

ing icts for users with mild cognitive impairment: A

usability study. International Journal of Environmen-

tal Research and Public Health, 17:5153.

Cerezo, Eva, B.-C. B. S. (2020). Therapeutic activities for

elderly people based on tangible interaction. pages

281–290.

Chen, W. (2012). Multitouch tabletop technology for peo-

ple with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the

literature. Procedia Computer Science, 14:198–207.

Cl

´

ement, Nassif, L.-M. (1997). Mise au point et contribu-

tion

`

a la validation d’une version franc¸aise br

`

eve de la

geriatric depression scale de yesavage. L’Enc

´

ephale,

23:91–99.

Danassi (2014). Sociable: A surface computing platform

empowering effective cognitive training for healthy

and cognitively impaired elderly. Advances in Exper-

imental Medicine and Biology, 821:129–130.

Derouesne, Poitreneau, H.-K. D. L. (1999). Le mini-

mental state examination (mmse) : un outil pratique

pour l’

´

evaluation cognitif des patients par le clinicien,

version franc¸aise consensuelle. La Presse m

´

edicale,

28(21):1141–1148.

Dillenbourg, Pierre, E.-M. (2011). Interactive tabletops in

education. I. J. Computer-Supported Collaborative

Learning, 6:491–514.

Elboim-Gabyzon, Weiss, D.-S. (2021). Effect of age on

the touchscreen manipulation ability of community-

dwelling adults. International journal of environmen-

tal research and public health, 18(4):2094.

Elrod, Scott, B. R.-G. R. G. D.-H. F. J. W. L. D. M. K. P. E.

P. K. T. J. W. B. (1992). Liveboard: A large interactive

display supporting group meetings, presentations, and

remote collaboration. pages 599–607.

Folstein, Folstein, M. (1975). Mini-mental state”: A practi-

cal method for grading the cognitive state of patients

for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research,

12(3):189–198.

Gamberini, Martino, S. S.-F. I. A. A. (2009). Eldergames

project: An innovative mixed reality table-top solution

to preserve cognitive functions in elderly people. 2009

2nd Conference on Human System Interactions.

Geller (2006). Interactive tabletop exhibits in museums and

galleries. IEEE computer graphics and applications,

26(5):6–11.

Groenewoud, Hanny, L. J.-S. Y. A. A.-J. P. G. M. (2017).

People with dementia playing casual games on a

tablet. Gerontechnology, 16:37–47.

Hôsea: A Touch Table for Cognitive and Motor Rehabilitation for the Elderly - A Preliminary Study

425

Gronier, B. (2021). Psychometric evaluation of the f-

sus: Creation and validation of the french version of

the system usability scale. International Journal of

Human-Computer Interaction, page 1–12.

Guay, Vallerand, B. (2000). On the assessment of situa-

tional intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The situa-

tional motivation scale (sims). Motivation and Emo-

tion, 24.

Hart, S. (1988). Development of nasa-tlx (task load in-

dex): Results of empirical and theoretical research.

P. A. Hancock and N. Meshkati (Eds.) Human Men-

tal Workload. Amsterdam: North Holland Press.

Hyry, Jaakko, K. M.-Y. G. T. T.-S. C. K. H. P. P. (2017).

Design of assistive tabletop projector-camera system

for the elderly with cognitive and motor skill impair-

ments. ITE Transactions on Media Technology and

Applications, 5:57–66.

Iancu, Ioana, I. B. (2020). Designing mobile technology for

elderly. a theoretical overview. Technological Fore-

casting and Social Change, 155:119977.

Ijsselsteijn, Wijnand, N. H. H. P. K. D. K. Y. (2007). Digi-

tal game design for elderly users. Proceedings of the

2007 Conference on Future Play, Future Play ’07.

Jung, Kim, P. K. (2013). E-core (embodied cognitive re-

habilitation): A cognitive rehabilitation system using

tangible tabletop interface. Biosystems & Biorobotics,

1:893–897.

Kawamura, Yura, H. H. M. T. M. (1992). Online recog-

nition of freely handwritten japanese characters us-

ing directional feature densities. Proceedings, 11th

IAPR International Conference on Pattern Recog-

nition. Vol.II. Conference B: Pattern Recognition

Methodology and Systems, pages 183–186.

Kubicki, S

´

ebastien, W. M. L. S. K. C. (2015). Rfid inter-

active tabletop application with tangible objects: ex-

ploratory study to observe young children’ behaviors.

Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 19:1259–1274.

Lee, Seyeon, O. H. S. C.-K. D. Y. Y. (2021). Mobile

game design guide to improve gaming experience for

the middle-aged and older adult population: User-

centered design approach. JMIR Serious Games,

9:e24449.

Liao, Jing, L. J. W. Q.-Z. M. Z. L. (2018). A review

of age-related characteristics for touch-based perfor-

mance and experience.

Loenen (2007). Entertaible: A solution for social gaming

experiences.

Lu, Lin, Y. (2017). Development and evaluation of a cog-

nitive training game for older people: A design-based

approach. Front Psychol, 8:1837.

Mahmud, Abdullah & Mubin, O. S.-S. M. J.-b. (2008). De-

signing and evaluating the tabletop game experience

for senior citizens. ACM International Conference

Proceeding Series, 358:403–406.

Maincent (2001). Le nasa tlx, traduit en franc¸ais et adapt

´

e

pour le laboratoire d’etudes et d’analyses de la cogni-

tion et des mod

`

eles, lyon.

Shen (2006). Informing the design of direct-touch table-

tops. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications,

26(5):36–46.

Tajudeen, Farzana, B. N. T. M.-M. M. S.-I. J. J. (2022).

Understanding user requirements for a senior-friendly

mobile health application. Geriatrics, 7:110.

Ten Brinke, Davis, B. L.-A. (2017). Effects of computer-

ized cognitive training on neuroimaging outcomes in

older adults: a systematic review. BMC geriatrics,

17(1):139.

¨

Oring, Tanja, S. A. S.-A. (2019). Exploring gesture-based

interaction techniques in multi-display environments

with mobile phones and a multi-touch table.

HUCAPP 2024 - 8th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

426