The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’

Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations

John McConnell

1a

, Yair Levy

2b

, Marti Snyder

3c

and Ling Wang

2d

1

Johns Hopkins, 5801 Smith Ave., Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.A.

2

College of Computing and Engineering, Nova Southeastern University, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, U.S.A.

3

Learning and Education Center, Nova Southeastern University, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, U.S.A.

Keywords: Linux Server Administrators, Cognitive Heuristics, Cognitive Biases, Information Security Policy Compliance,

Healthcare Cybersecurity.

Abstract: Information Security Policy (ISP) compliance is crucial to healthcare organizations due to the potential for

data breaches. The healthcare industry relies heavily on Linux servers to house electronically Protected Health

Information (ePHI) due to their inherited lower volume of known vulnerabilities. However, Linux Server

Administrators appear to be more relaxed than other server administrators when it comes to ISP compliance.

Prior research suggests that the use of cognitive heuristics and biases may negatively influence threat appraisal

and coping appraisal, while ultimately impacting ISP compliance. Thus, the goal of our study was to

empirically assess the effect of cognitive heuristics, biases, and knowledge-sharing level on actual ISP

compliance measured based on actual security setting adjustments. Aside from the novel measure of actual

ISP compliance, we developed a survey instrument based on prior validated instruments to measure cognitive

heuristics and biases. A group of 42 Linux Server Administrators who oversee the servers at a major

healthcare organization participated in our study. Additionally, an intervention in the form of hands-on

cybersecurity training, periodic security update emails, and Linux-focused tabletop exercises was introduced.

Our results indicated that information security knowledge-sharing significantly influenced both cognitive

heuristics and biases. Conclusions and discussions are provided.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the massive avalanche of data breaches in recent

years, information security is rising to the radar of

organizational leaders (Levy & Gafni, 2021). The

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)’s Internet

Crime Report estimated that in 2021, the cost of

cybercrime reached $6.9 trillion (FBI, 2022, March

22). With the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the

healthcare industry experienced a massive wave of

cyber-attacks and, unfortunately, many successful

data breaches (Gafni & Pavel, 2021). Prior reports by

the FBI’s Internet Computer Complaint Center (IC3)

from 2021 that included COVID-19 cyber-attacks

statistics, documented over 230% increase in

cyberattacks in 2020 from the prior year, many of

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5913-743X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8994-6497

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9177-9504

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9202-6501

these targeted the healthcare industry (FBI, 2021).

The number of healthcare breaches that resulted in at

least 500 records stolen increased from 220 in 2013

to 550 (250% increase) in 2020 (U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights,

2023). From early 2012 to early 2023, a total of

301,013,431 patient records were breached in 50

states and the District of Columbia impacting

physician practices, health plans, and hospitals (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services Office for

Civil Rights, 2023). During the same period, server-

related incidents resulted in the loss of 229,563,942

individual electronic Protected Health Information

(ePHI) records (U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services Office for Civil Rights, 2023).

Healthcare-related server breaches represented

30

McConnell, J., Levy, Y., Snyder, M. and Wang, L.

The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’ Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations.

DOI: 10.5220/0012297000003648

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2024), pages 30-41

ISBN: 978-989-758-683-5; ISSN: 2184-4356

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

79.6% of the total records breached. The healthcare

industry is a complicated network of hospitals,

providers, independent laboratories, pharmacies,

imaging centers, insurance companies, and public

health departments centered on patients’ health

(Dixon, 2016). The ability to safeguard patients’ ePHI

in all three data states (at rest, at processing, & at

transit) is key to improving patient medical outcomes

and lowering the cost of healthcare (Office of the

National Coordinator for Health Information

Technology, n.d.). Server administrators’ compliance

with the Information Security Policy (ISP) of the

organization is key to safeguarding patients’ ePHI

and minimizing the risk of data breaches (Chen et al.,

2018). While many organizations’ servers are

Windows-based, a significant number of larger, back-

end systems, especially at large-scale healthcare

organizations, are Linux-based to capitalize on

increased server processing power, reliability,

assumed increased information security, and

clustering technology (Beuchelt, 2017). As of

October 2023, it was reported that Linux servers

represent 82.0% of active Web servers worldwide

(W3Techs, 2023). Globally, Linux variants represent

67.21% of the operating system market share

(GlobalStats, 2023). Adequately managing servers’

security reduces the risk of systems disruption, loss of

confidential ePHI, harm to organizational reputation,

potential loss of revenue, and financial loss due to

litigation or fines (Donaldson et al., 2015). Server

administrators are humans, and like other individuals,

they use judgment to make decisions daily. Cognitive

heuristics are mental shortcuts that individuals use to

quickly assess a situation and determine an adequate,

though frequently flawed, conclusion (Kahneman,

2011). Cognitive biases describe how information

framing and context influence decision-making,

which departs from normal rational theory (Gilovich

& Griffin, 2013). Prior research provided strong

evidence that knowledge-sharing related to

information security issues among users, especially

Information Technology (IT) professionals, is critical

for the mitigation of cybersecurity risks in

organizations (Safa et al., 2016). A significant

volume of prior research related to security

compliance is based on self-reported compliance

(Mandiant, 2013). Moreover, self-reported behavior

has been documented in prior research to have a

limited correlation with actual human behavior

(Mahalingham et al., 2023). In the context of

information security, Wash et al. (2017) indicated that

“There are many user decisions that people do not

self-report accurately. When studying these

[information security] decisions, it is important to

measure actual behaviors rather than relying on self-

reports” (p. 2231). Additionally, self-reported

behavior frequently measures intention rather than

actual secure behaviors (Chen & Tyran, 2023). Thus,

the goal of our study was to empirically assess the

effect of cognitive heuristics, biases, and knowledge-

sharing levels on actual ISP compliance by Linux

Server Administrators. Moreover, we have

intentionally elected to craft multi-point metrics to

assess actual ISP compliance based on security

setting adjustments that the Linux Server

Administrators performed or not. Furthermore, we

have developed an intervention in the form of a set of

targeted Linux-focused tabletop exercises that

included hands-on interactive information security

challenges and provided the Linux Server

Administrators a platform for knowledge-sharing

when it comes to ISP compliance and cybersecurity

issues. Our two main Research Questions (RQs) for

this study were:

RQ1: What is the role of knowledge-sharing level,

cognitive heuristics, and cognitive biases on the

Linux Server Administrators’ actual ISP

compliance level mediated by their perceptions

of severity and vulnerabilities along with

efficacy (self-efficacy & efficacy-response) in

the healthcare industry?

RQ2: What is the role of an intervention in the form

of updated cybersecurity training, periodic

security update emails, and Linux-focused

tabletop excursuses on the Linux Server

Administrators’ actual ISP compliance level in

the healthcare industry?

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Human Factor in ISP Compliance

The human aspects of information security must be

understood to reduce the risk of data breaches

(Antonucci et al., 2021). Users’ ignorance, apathy,

errors, resistance, and mischievous nature can result

in human-caused data breaches (Pollock et al., 2021).

Recently, the 2022 Data Breach Investigation Report

led by Verizon (2022) with contributions from 83

federal and state law enforcement agencies, noted that

so far in the first half of 2022 alone, “82% of breaches

involve the human element—something the silicon

isn’t going to be mitigating” (p. 45). To strengthen the

human aspect of information security, ISPs are

developed, which enhance cybersecurity, and

physical security, decrease vulnerability to data

The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’ Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations

31

breaches, as well as ensure legal and regulatory

compliance (Pollock et al., 2021). Unfortunately,

employee noncompliance with ISP is the key threat to

organizational information security (Pollock et al.,

2021). Sadok et al. (2020) found that by connecting

ISPs with subject matter experts, work processes

improved overall ISP compliance. This was relevant

to the current research as the Linux Server

Administrators are the subject matter experts for the

organizational servers that they manage, yet they are

human too. Kahneman (2011) referred to the two

cognitive systems of decision-making as ‘System

One’ and ‘System Two’. System One lies outside of

individuals’ awareness and is intuitive, implicit, and

involuntary (Cooper et al., 2021). System Two, the

reasoning and analytical system, is where deliberate

thought occurs (Cooper et al., 2021; Kahneman,

2011). System Two is activated whenever a problem

presents itself to which System One cannot provide a

reasonable answer (Antonucci et al., 2021;

Kahneman, 2011). Several heuristics and biases may

negatively impact threat appraisal and coping

appraisal including the cognitive heuristic, optimism

bias, and confirmation bias (Kahneman, 2011). Use

of these heuristics and biases can result in

inappropriately low judgment of risk or an

overinflated estimation of coping skills, or human

error (Kahneman, 2011; Pollock et al., 2021).

Optimism bias can result in dangerous neglect of risks

(Rhee et al., 2012). This bias can enhance perceived

invulnerability to negative events and lead to

inappropriately high levels of risky behaviors

(Pollock et al., 2021; Rhee et al., 2012). To judge the

probability of an event, an individual may assess the

availability of associations related to the event

(Kahneman, 2011). It is cognitively easier to estimate

a probability based on the ease with which one recalls

occurrences of a similar event (Kahneman, 2011).

Pachur et al. (2012) found that the availability

heuristic significantly influenced perceived risk.

Confirmation bias and optimism bias are closely

related and can significantly influence decision-

making (Kahneman, 2011). With confirmation bias,

one gives greater validity to information that supports

one’s beliefs. Tsohou et al. (2015) found that

confirmation bias led individuals to inappropriately

assess information security threats. Kahneman (2011)

identified confirmation bias as a System One

heuristic, and it is, therefore, easily activated when

making decisions. Building on Kahneman’s (2011)

heuristics and biases work in assessing risk, this study

investigated how the availability heuristic,

confirmation bias, and optimism bias influenced

Linux Server Administrators’ implementation of

information security controls.

2.2 Knowledge-Sharing in Information

Security

Flores et al. (2014) emphasized the importance of

knowledge-sharing processes in organizations. The

sharing of information security knowledge,

experience, and insights can improve organizational

performance and help enhance the overall

organizational cybersecurity posture (Safa & Von

Solms, 2016). Prior research provided ample

evidence that information security knowledge is

frequently scattered throughout organizations and

many organizations have not developed an effective

program to share critical knowledge within them

(Safa & Von Solms, 2016). Furthermore, prior

research indicated that one effective way of

increasing information security knowledge-sharing,

and cybersecurity skills is through effective SETA

programs (Safa & Von Solms, 2016). It appears that

the development of a formal means for information

security knowledge-sharing may help to foster the

sharing of ideas, experiences, tools, and processes to

improve the information security of organizational

information systems assets. Making users aware of

the current and evolving cyber risks, threats,

vulnerabilities, and their severities, the speed with

which the threats propagate, as well as the potential

impact on the organization is crucial to ISP

compliance (Safa et al., 2016; Siponen et al., 2014).

Safa and Van Solms (2016) found that information

security knowledge-sharing benefited businesses,

increased employee information security self-

efficacy, and improved ISP compliance.

2.3 Protection Motivation Theory

(PMT) and ISP Compliance

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) was developed

by Rogers (1975) to understand how fear appeals

influenced behaviors. PMT is frequently used to

understand compliance with ISPs, and as a result, is

of great relevance to this study (Hanus & Wu, 2016;

Jansen & van Schaik, 2018). Two key constructs in

PMT are coping appraisal and threat appraisal

(Rogers, 1975). Coping appraisal, which includes

self-efficacy and response-efficacy, is an assessment

of how the individual can cope with, adapt to, and

change behavior to avoid harm (Rogers & Prentice-

Dunn, 1997). Threat appraisal is an assessment of the

perceived severity of a threatening event or attack

vector, also noted as “perceived severity” in short,

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

32

and the perceived probability of the occurrence of

such event that the individual attributes to the

threatening event or attack vector, also noted as

“perceived vulnerability” (Rogers & Prentice-Dunn,

1997). Prior studies found threat appraisal to be

positively correlated with ISP compliance intention

(Chen & Tyran, 2023), yet we question the validity of

such work, as noted previously when it comes to the

relationship between self-reported intentions and

actual behavior of individuals in the context of ISP

compliance.

2.4 Security Education, Training, and

Awareness (SETA) and ISP

Compliance

Security Education, Training, and Awareness

(SETA) programs are a means for organizations to

increase awareness and minimize the risk of insider-

caused information security failures or data breaches

(Chen et al., 2018). Prior research indicated that

engaging the users and ‘audience appropriate’ SETA

programs, positively influences self-efficacy and ISP

compliance (Chen et al., 2018; Pattinson et al., 2019).

Focusing the SETA program on the responsibilities of

the participants improved engagement, information

retention, and compliance (Schroeder, 2017). Posey

et al. (2015) found that SETA programs positively

correlated with both perceived severity and response-

efficacy.

2.5 Prior ISP Compliance Research

Gaps

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability

Act (HIPAA) poses penalties and settlements levied

on healthcare systems and insurance companies

totaling millions of dollars yearly (HIPAA Journal,

2022). Given the potential financial liabilities

associated with data breaches and privacy violations,

it is imperative that healthcare organizations secure

their computing resources by following the HIPAA

and Health Information Technology for Economic

and Clinical Health (HITECH) guidelines. The

HIPAA Security Rule provided specifications and

standards that covered healthcare entities should

implement to help ensure the Confidentiality,

Integrity, and Availability (CIA) of ePHI (Koch,

2017). These policies and guidelines, however, will

not protect PII/ePHI data if they are not properly

implemented within the technical infrastructure

(Dixon, 2016). At the same time, HIPAA and other

governmental regulations require healthcare

organizations to develop well-articulated ISPs both

for their general employees and their IT employees.

As such, lack of ISP compliance appears to be a major

threat vector. However, based on our review of the

literature, there are several notable gaps that this

study investigated. First, research on ISP compliance

has focused primarily on end-users. While they are

critical to organizational information security, server

administrators have the highest privilege levels and

access to the critical data stored in the organization

(Beuchelt, 2017). Siponen et al. (2014) identified

employee failure to follow ISPs as a key threat to the

security of an organization. An additional risk is that

employees can make errors due to cognitive

limitations, task demands, as well as organizational,

social, or environmental factors (Safa & Von Solms,

2016). Most of these studies have evaluated end-user

ISP compliance intention (Chen & Tyran, 2023).

Behavioral compliance of Linux Server

Administrators, however, can be even more crucial as

the data hosted on the back-end Linux servers

frequently contain ePHI, PII, or financial data

(Beuchelt, 2017). Additionally, server administrators

are responsible for configuring security controls to

protect organizational servers and data (Beuchelt,

2017). Information security threat vectors for servers

include network- security-, and operating systems

misconfiguration, as well as unpatched systems or

device firmware, and privileged account escalation

(Caballero, 2013). Given these risks, it is important to

understand how to improve server administrators’

actual ISP compliance. Second, it appears that

research is scarce into the effectiveness of a SETA

program that focuses on the job activities of server

administrators, while they hold the most privileged

access at most organizations. It appears that most

SETA-related research studies have been focused on

organizational employees (Sarabadani et al., 2022).

As such, another innovation of our study is that it

investigated how a specially designed SETA

workshop affected heuristics and biases, as well as

actual ISP compliance of Linux Server

Administrators. Third, cognitive heuristics can lead to

biased decision-making as well as biased evaluation

of information security threats and risks (Pollock et

al., 2021). The inappropriate use of heuristics and

biases may prevent Linux Server Administrators from

correctly assessing the information security risks to

the organizational servers that they are overseeing,

which may reduce actual ISP compliance.

Participant-focused SETA programs can be an

effective means of reducing the use of cognitive

heuristics, biases, and improving actual ISP

compliance (Sarabadani et al., 2022). Fourth, while

Posey et al. (2015) integrated SETA and PMT, they

The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’ Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations

33

appear to omit in their assessment the influences of

heuristics and biases on program effectiveness, which

our study attempted to do. Finally, while behavioral

intention is frequently taken as an indicator of

behavior (Chen & Tyran, 2023), it was noted by

several prior research (e.g., Mahalingham et al.,

2023) that intention differed significantly from actual

behavior in the context of implementation of security

controls. Comparing baseline (pre) and post-

intervention information security scans allowed the

present research to analyze actual information

security measures implemented by the server

administrators. Additionally, the use of optimism

bias, confirmation bias, or the availability heuristic

can lead to a fundamental underestimation of risk and

result in reduced ISP compliance (Tsohou et al.,

2015). Thus, it appears that there is great value in

further understanding how tailored SETA and

knowledge management programs, developed to

address the unique job functions of Linux Server

Administrators, influence their use of cognitive

heuristics, biases, information security knowledge-

sharing, and ultimately test if it has any effect on their

actual ISP compliance.

3 DEVELOPMENT OF

HYPOTHESES

As indicated above from prior research, the

development of an information security knowledge-

sharing culture is an important goal for any

organization that has critical information systems

assets (Safa & Van Solms, 2016). Flores et al. (2014)

emphasized the importance of knowledge-sharing

processes in organizations. SETA workshops and

online training provide formal means of information

security knowledge-sharing within organizations

(Safa & Von Solms, 2016). These processes provided

a starting point for the present research’s cognitive

model of ISP compliance. Security knowledge-

sharing processes are theorized to directly influence

the three studied cognitive heuristics and biases used

by Linux Server Administrators (Kahneman, 2003).

Therefore, our first set of hypotheses noted in the null

form were:

H1: Information security knowledge-sharing will

have no significant influence on Linux Server

Administrators’ use of the availability heuristic.

H2: Information security knowledge-sharing will

have no significant influence on Linux Server

Administrators’ use of optimism bias.

H3: Information security knowledge-sharing will

have no significant influence on Linux Server

Administrators’ use of confirmation bias.

While prior research indicated that knowledge-

sharing has a significant influence on the three

cognitive heuristics and biases (Kahneman, 2003), in

this study we will assess if these also hold true in the

context of information security, especially with Linux

Server Administrators. Moreover, prior research

indicated that heuristics and biases influence threat

appraisal and coping appraisal from PMT

(Kahneman, 2011; Pachur et al., 2012; Rogers &

Prentice-Dunn, 1997). The key components of PMT,

threat appraisal and coping appraisal, have been

found in prior literature to be significantly influenced

by SETA programs and are, therefore, critical to

research into ISP compliance (Safa et al., 2016).

Dang-Pham et al. (2017) found that information

security awareness also improved the diffusion of

knowledge-sharing, in the context of information

systems, throughout the organization. Finally, threat

appraisal and coping appraisal have been shown in

the literature to influence compliance behavior (Safa

et al., 2016). As such, our study proposed to assess

such relationship in the contexts of ISP compliance of

Linux Server Administrators to include the following

four key areas: (1) SETA; (2) heuristics and biases;

(3) PMT, i.e., perceived severity, and perceived

vulnerability; as well as (4) actual ISP compliance.

Therefore, we hypothesized that:

H4: Availability heuristic will have no significant

influence on Linux Server Administrators’ (a)

perceived severity, and (b) perceived

vulnerability.

H5: Optimism bias will have no significant

influence on Linux Server Administrators’ (a)

perceived severity, (b) perceived vulnerability,

(c) self-efficacy

, and (d) response-efficacy.

H6: Confirmation bias will have no significant

influence on Linux Server Administrators’ (a)

perceived severity, (b) perceived vulnerability,

(c) self-efficacy, and (d) response-efficacy.

H7a: Perceived severity will have no significant

influence on Linux Server Administrators’

actual ISP compliance.

H7b: Perceived vulnerability will have no significant

influence on Linux Server Administrators’

actual ISP compliance.

H8a: Self-efficacy will have no significant influence

on Linux Server Administrators’ actual ISP

compliance.

H8b: Response-efficacy will have no significant

influence on Linux Server Administrators’

actual ISP compliance.

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

34

All hypotheses are noted in the null form for

uniformity and testing purposes.

4 METHODOLOGY

The main aim and objective of our study was to

formulate a cognitive processing model to test the two

previously introduced research questions via a set of

hypotheses outlined above. Additionally, we

developed an integrated information security

knowledge-sharing model following the Information

Security Organizational Knowledge-sharing

Framework proposed by Flores et al. (2014). We have

also followed Kahneman, his colleagues, and other

researchers who extended his work into the

information security field on cognitive heuristics as

well as bias measures (Antonucci et al., 2021; Cooper

et al., 2021; Pollock et al., 2021), along with PMT

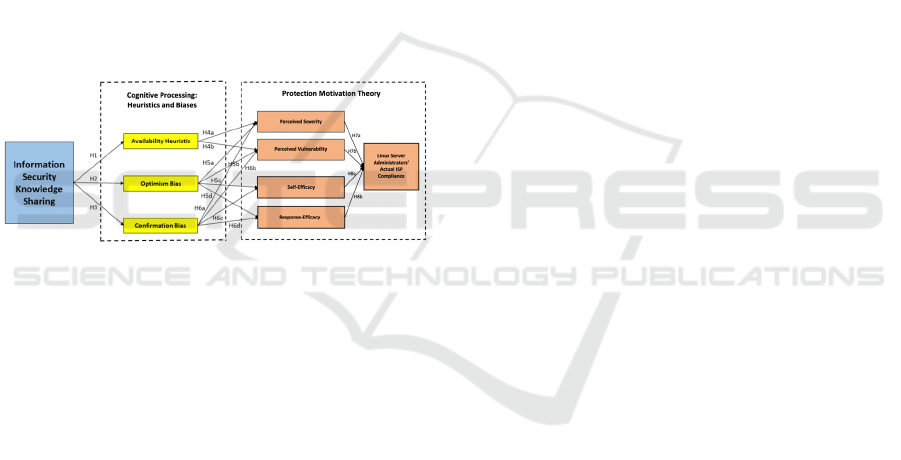

constructs (Posey et al., 2015) as depicted in Figure

1. The proposed model addresses RQ1.

Figure 1: The Research Model on the Factors Impacting

Actual Linux Server Administrators’ ISP Compliance.

4.1 Measures and the Research Model

This quantitative research was conducted in a pretest

and posttest design. The assessment included two

parts: Part 1 – Survey instrument, and Part 2 – Actual

ISP Compliance metrics, both were collected before

and 90 days following the intervention – the Linux-

focused SETA workshop. In Part 1, participants

completed a survey instrument that included

questions for Optimism Bias (OB), Self-Efficacy

(SE), Response-Efficacy (RE), Perceived

Vulnerability (PV), Perceived Severity (PS), and

Information Security Knowledge-sharing (ISKS),

which were adapted from previously validated

instruments used by Safa and Von Solms (2016),

Moqbel and Bartelt (2015), Ifinedo (2012), Hanus

and Wu (2016), Rhee et al. (2012), Siponen et al.

(2014), as well as Safa et al. (2016). Questions were

modified to reflect the focus on servers rather than

personal computers. The questions used to assess a 7-

point Likert scale ranging from (1) Strongly Disagree

to (7) Strongly Agree. We developed the questions for

the Cognitive Heuristic (CH) and Confirmation Bias

(CB) following prior work by Kahneman, his

colleagues, Fischer et al. (2011), and other

researchers noted above. Confirmatory Bias was

measured using a fictional scenario, similar to the

technique of Fischer et al. (2011) where participants

are presented with a scenario, asked to make an initial

decision, and then provided six confirming and six

disconfirming bits of additional information they can

choose to review, and then asked to choose again on

the initial fictional scenario. The level of

Confirmatory Bias was determined by subtracting the

number of disconfirming choices (Cons) selected

from the confirming choices (Pros) selected (Fischer

et al., 2011; Gertner et al., 2016). The survey was

pilot-tested with 17 individuals who evaluated the

flow of the survey, the wording of the questions, as

well as the reliability and validity of the instrument.

Additionally, the participants took part in our

developed Linux-focused SETA workshop and an

online hands-on cybersecurity lab. The Linux-

focused SETA workshop and cyber lab were designed

with the following goals: (1) help increase

cybersecurity awareness among Linux Server

Administrators; (2) help Linux Server Administrators

mitigate information security risk for the

organizational servers that they manage; (3) Teach

Linux Server Administrators on how to perform basic

penetration testing and server ISP analysis using

common tools; (4) Provide Linux Server

Administrators hands-on cloud-based cyber lab to

teach them the fundamentals of network security tools

(WireShark, NMAP, Metasploit, etc.); (5) Provide

environment for Linux Server Administrators to

connect with other administrators to increase

knowledge-sharing and collaboration.

In Part 2 when assessing for the actual ISP

compliance, we used five information data points that

were extracted directly from the Linux servers.

Specifically, we wanted these data points to provide

an accurate assessment of the actual security controls

implemented on each server that is managed by the

Linux Server Administrators. All five data points are

requirements in the organization’s ISP for Linux

servers. As such, security scans, reports, and scripts

were run on all Linux servers associated with each

participant before, and 90 days following the

intervention – the Linux-focused SETA workshop.

Following that, the five security data points metrics

we used to assess actual ISP compliance (our

dependent variable) by the Linux Server

Administrators included:

1. Percentage of Linux servers using centralized log

management, measured by a single data point

The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’ Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations

35

extracted from the Security Incident and Event

Management (SIEM) tool.

2. Percentage of Linux servers with recorded

Tenable Nessus data, measured by a single data

point extracted from the organization’s SIEM

Tenable dashboard.

3. Percentage of Linux servers blocking telnet,

FTP, and remote services ports, measured by a

single data point extracted from NMAP scan

report.

4. Percentage of Linux servers using Multi-Factor

Authentication (MFA), measured by a single

data point extracted from the organization’s

centralized Single-Sign-On (SSO) system.

5. Percentage of Linux servers that have had recent

software updates, measured by a single data point

extracted from the organization’s SIEM Linux

inventory dashboard.

4.2 Study Participants

All Linux servers and Server Administrators were

identified from a single healthcare organization’s

configuration management database. The

organization is a multi-hospital health system and

teaching university in the mid-Atlantic U.S. region.

Invitations to participate emails were sent to all server

administrators and their direct managers. The

invitation described our study, the Linux-focused

SETA workshop content, and the hands-on cyber lab.

Invitation responses included 53 potential

participants, where 30 of them were identified as

primarily Linux Server Administrators. Some

individuals (12) were identified as split responsibility

for both Linux and Windows servers. Four

individuals identified themselves as Windows-only

server administrators; seven individuals did not have

any responsibility for servers. A total of 42 who

identified both as the primary as well as the split

(Linux & Windows) participated in the study and

completed all the study protocols. The Linux-focused

SETA workshop had significant support from the

organizational leadership, including the Chief

Information Officer (CIO), Chief Information

Security Officer (CISO), the IT security team, as well

as directors and managers at the organization. We

believe that this organizational leadership support led

to such a high response rate. Unfortunately, due to the

COVID-19 pandemic, the Linux-focused SETA

workshop was conducted online via Zoom. The cyber

lab followed the workshop and provided hands-on

experience using information security tools in a

controlled environment. The module utilized two

Linux Virtual Machines (VMs) and consisted of

challenges associated with locating, enumerating, and

exploiting a Linux server. EDURange (2019)

provides cloud-based resources for security education

of students and researchers. A new EDURange

Metasploit scenario was developed as part of this

study and allowed participants to perform penetration

testing using NMAP and the Metasploit Framework.

Following the Linux-focused SETA workshop,

every three weeks, information security update emails

were sent to participants. A total of six emails were

sent which provided updates regarding recently

identified vulnerabilities, relevant information

security alerts, breach announcements, FBI InfraGard

(https://www.infragard.org/) updates, ransomware

events, as well as information about Tripwire and

Rootkit Hunter applications. The goals of the

information security update emails were to see if the

current information security awareness, information

security knowledge-sharing, and information security

recommendations made during the workshop were

being neglected, retained, or enhanced. Finally, 90

days after the workshop, an email was sent to all

Linux Server Administrators who participated in the

study to complete the online post-intervention survey.

Also, information security scans and report

extractions were used to quantify the changes made

by the administrators before and again 90 days after

the workshop, as the metrics for the actual ISP

compliance. The measures comparisons of before and

after the above-mentioned intervention were set to

address RQ2.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Results of the PLS-SEM Analysis

Partial Least Squares - Structural Equation Modeling

(PLS-SEM) has been used extensively in prior

research to test complex models in information

security (Hanus & Wu, 2016; Ifinedo, 2012; Rhee et

al., 2012). PLS-SEM has characteristics relevant to

the present research including acceptance of small

sample sizes, no assumption of data normality,

variety of scales of measurement, and ability to

handle complex models (Hair et al., 2017). Hair et al.

(2017) indicated that for a significance level of 5%

with a maximum of three arrows pointing toward a

construct (threat appraisal), a minimum R2 of 0.25

requires a 33-participant sample size and a minimum

R2 of 0.50 requires 14 participants. SmartPLS 3.3.2

was used to perform analyses of our collected data.

The data analysis was completed in two phases. First

the pre-workshop and post-workshop data were

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

36

collected and analyzed using PLS-SEM. The data

from the surveys were exported from Qualtrics to a

Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The actual ISP

compliance metrics were collected, aggregated, and

merged with the survey data to provide a single

comma-delimited file for input into SmartPLS. The

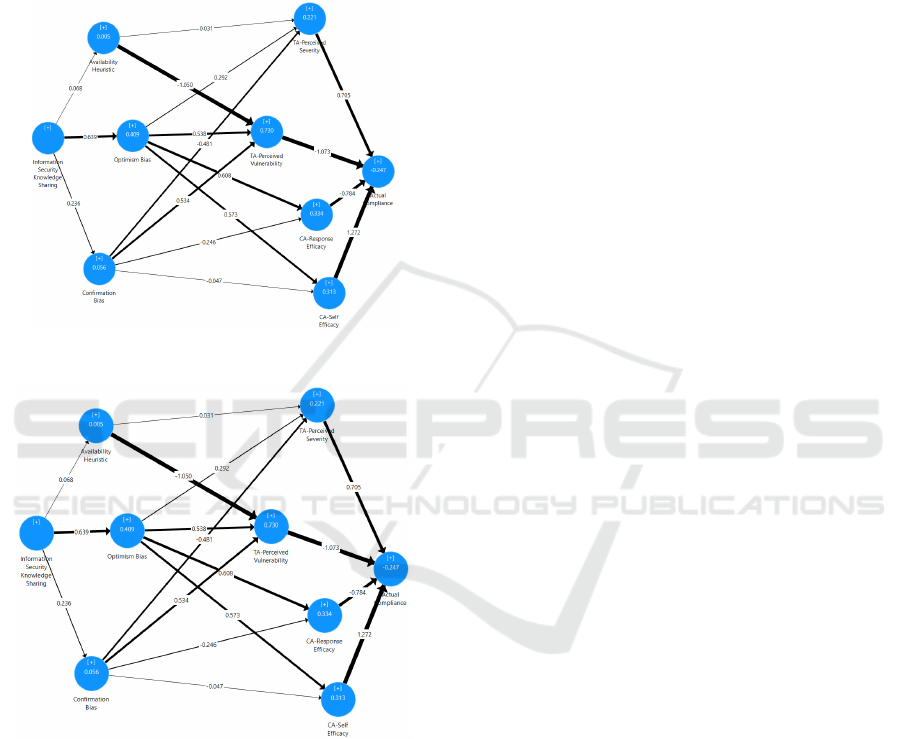

pre-workshop (a) and post-workshop (b) PLS-SEM

analysis results are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: (a) Pre-workshop PLS-SEM Analysis Results.

Figure 2: (b) Post-workshop PLS-SEM Analysis Results.

5.2 Results of the PLS-MGA Analysis

The next step in the analysis of the data was to

perform SmartPLS Multigroup Analysis (PLS-

MGA). Both pre-workshop and post-workshop

datasets were merged into a single data set, and a

group identifier column was added to differentiate

before-workshop and after-workshop data, which was

then used for the MGA. The measurement model was

assessed for internal consistency reliability, indicator

reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant

validity (Hair et al., 2017). The structural model was

assessed for collinearity among the constructs, as well

as the relevance and significance of the path

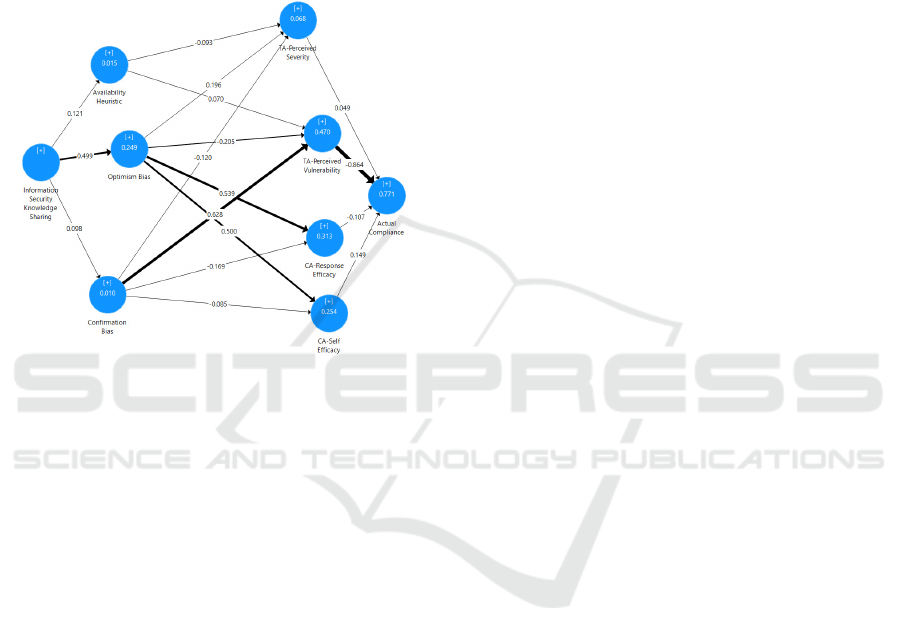

coefficients (Hair et al., 2017). The combined groups

model with R

2

and path coefficients can be found in

Figure 3.

Key paths in the MGA included Perceived

Vulnerability

Actual Compliance (-0.864),

Confirmation Bias

Perceived Vulnerability

(0.628), Optimism Bias

Response-Efficacy

(0.539), and Information Security Knowledge-

sharing

Optimism Bias (0.499). Bootstrapping

was performed for path significance and in the

analysis seven paths were significant: Confirmation

Bias Perceived Vulnerability (p < 0.001),

Information Security Knowledge-sharing

Optimism Bias (p < 0.001), Optimism Bias

Response Efficacy (p < 0.001), Optimism Bias

Self-Efficacy (p < 0.001), Optimism Bias

Perceived Severity (P < 0.047), Optimism Bias

Perceived Vulnerability (p = 0.022), and Perceived

Vulnerability

Actual ISP Compliance (p < 0.001).

The effect size (f²) was used to assess how constructs

contribute to the explaining power of other

constructs. In the analysis, strong positive effects:

Confirmation Bias

Perceived Vulnerability

(0.602), Perceived Vulnerability

Actual ISP

Compliance (3.142), and moderate positive effects

for Optimism Bias

Response-Efficacy (0.423),

Optimism Bias

Self-Efficacy (0.334), and

Information Security Knowledge-sharing

Optimism Bias (0.331). Finally, blindfolding was

used to assess predictive power using the Stone-

Geisser values (Hair et al., 2017). In the MGA, strong

predictive power was found for actual compliance

(0.352), moderate predictive power for Self-Efficacy

(0.185), weak predictive power for Optimism Bias

(0.146), and Perceived Vulnerability (0.086).

In the next phase of analysis, the heuristics and

biases scores were evaluated for changes. Indicator

scores for each construct were compared before and

after the intervention using paired t-tests to assess if

significant changes occurred for each administrator.

The results indicate that the availability heuristic (p <

0.001, t = 3.914) and confirmation bias (p < 0.001, t

= 7.723) had significant changes, but optimism bias

did not meet the t critical requirement (p = 0.01, t = -

2.353). Next, actual ISP compliance metrics scores

were compared before and after the intervention using

paired t-tests to assess if significant changes occurred

for each administrator. The results indicated that all

compliance metrics showed significant changes. A

total of 17 hypotheses were evaluated based on the

The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’ Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations

37

research model indicated in Figure 1. T-statistics

were used for H1-3 and PLS-MGA bootstrapping for

path significance analysis for H4a-H8b. The results

indicated that eight hypotheses were rejected (H1:

ISKS AH; H3: ISKS CB; H5a: OB PS; H5b:

OB PV; H5c: OB SE; H5d: OB RE; H6b:

CB PV; H7b: PV AC) and nine were accepted

(H2: ISKS OB; H4a: AH PS; H4b: AH PV;

H6a: CB PS; H6c: CB SE; H6d: CB RE;

H7a: PS AC; H8a: RE AC; H8b: SE AC).

Figure 3: Combined Groups PLS-SEM Multigroup

Analysis Results.

5.3 Model Evaluation, Validity, and

Reliability Measures

For the measurement model evaluation, internal

consistency reliability, composite reliability,

convergent validity, and discriminant validity were

assessed. Internal consistency reliability was evaluated

with Cronbach’s α. For established constructs results α

> 0.7 indicated internal consistency reliability and for

new constructs results α > 0.6 indicated internal

consistency reliability (Hair et al., 2017; Henseler et

al., 2016). The results indicated that perceived

vulnerability was below the threshold, aside from

Confirmation Bias (CB) which was measured by a

scenario following Fischer et al. (2011). All other

constructs met internal consistency reliability

requirements. Composite reliability was assessed with

ρ. For established constructs results ρ > 0.7 indicated

composite reliability and for new constructs, the cutoff

was ρ > 0.6 (Hair et al., 2017; Henseler et al., 2016).

The results indicated that perceived vulnerability was

below the threshold. All other constructs met

composite reliability requirements. Convergent

validity was assessed using the Average Variance

Extracted (AVE). Results > 0.5 indicate convergent

reliability (Ifinedo, 2012). Our results indicated that

perceived vulnerability was below the threshold. All

other constructs met convergent vulnerability

requirements. Finally, discriminant validity was

evaluated using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio

(HTMT). HTMT values < 0.85 indicated discriminant

validity (Hair et al., 2017; Kline, 2011).

6 DISCUSSIONS

Based on the analysis, the use of the availability

heuristic and confirmation bias were significantly

influenced by the Linux-focused SETA workshop and

the information security update emails (H1, H3).

Optimism bias did not meet the statistical cutoff for

significance (H3). It did, however, have a statistically

significant influence on all PMT constructs (H5a, H5b,

H5c, H5d). Also, the multigroup analysis showed

information security knowledge-sharing optimism bias

path was significant (H2). We believe that these results

point to the need for further investigation into

optimism bias. Confirmation bias had a significant

influence on perceived vulnerability (H6b). Lastly,

perceived vulnerability significantly influenced actual

ISP compliance (H8a). Both results were expected.

The failure of the availability heuristic to significantly

influence perceived severity (H4a) and perceived

vulnerability (H4b) was unexpected. We have adjusted

these survey questions for the construct of perceived

vulnerability based on prior literature in the context of

information security, however, we believe that

additional testing and adjustments to the survey

questions are needed. Confirmation bias did not have

the expected impact on perceived severity (H6a), self-

efficacy (H6c), or response-efficacy (H6d).

Confirmatory bias was tested using a fictional scenario,

similar to the technique of Fischer et al. (2011) where

participants are presented with a scenario, asked to

make an initial decision, and then provided six

confirming and six disconfirming bits of additional

information they can choose to review, followed by

asking them to choose again. This may have resulted

in historical bias due to having completed the survey

before and after the intervention. Actual ISP

compliance was not influenced by perceived severity

(H7a), response-efficacy (H8a), or self-efficacy (H8b).

This was not consistent with prior research that studied

ISP compliance intention and may be due to evaluating

actual ISP compliance instead. All the actual ISP

compliance metrics we used were novel and

demonstrated a significant increase between pre-

workshop and post-workshop analysis. In our findings,

port blocking and recent patching had the highest

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

38

degree of change and resulted from the intervention

and following knowledge-sharing emails. Interestingly,

these two measures were changes that the Linux Server

Administrators could make with no interaction with the

IT security team. Vulnerability scanning and MFA

require Linux Server Administrators to request the

organizational servers they manage to be registered.

After setup, no interaction with the IT security team is

usually necessary and information security scans could

be run and viewed by the administrators on demand.

Centralized log management demonstrated the lowest

change between pre- and post-workshop. This metric

required sending server log data to the IT security team

via syslog forwarding. That means that the interaction

level, effort required, and data exposure were

significantly higher than the other metrics. It was noted

in the data analysis that the four perceived vulnerability

survey items did not reach significance levels for

Cronbach’s α, ρ, and AVE. One question was used

from the work by Hanus and Wu (2016), one question

was from the work of Siponen et al. (2014), one

question was from the work of Ifinedo (2012), and a

final question was developed based on the

recommendation of a pilot-tester. While these survey

items were deemed sufficient by pilot testers, it appears

that the four questions did not combine into concise

indicators for the perceived vulnerability construct. We

recommend future research to evaluate these survey

items and come up with a more coherent measure for

the perceived vulnerability construct.

This study demonstrated the influence of security

training and knowledge-sharing on the use of cognitive

heuristics, confirmation, and optimism biases of a

unique group of systems administrators. In the

institution where the study was performed the Linux

administrators were spread out geographically and

organizationally. Many participants managed a

handful of servers with minimal interaction with other

administrators. The security workshop brought

together many of these individuals from across the

institution to help them become aware of the

vulnerabilities facing Linux servers and the risks

associated with not implementing security.

Additionally, the workshop introduced participants to

the key actions they can implement and the tools they

can use to protect their Linux servers. The post-

workshop security updates provided news about newly

identified vulnerabilities, recent breaches, and more

guidance on how to implement security tools discussed

in the workshop. The goal of the post-workshop

security updates was to maintain security awareness

and encourage the implementation of security controls.

The feedback from participants regarding the content

of the workshop and security updates was consistently

positive. The interaction of the participants in the new

Microsoft Teams channel was also encouraging.

Clearly, from an organizational perspective,

institutions that have Linux administrators need to

provide security awareness training that is relevant and

provides them with the knowledge and tools they need

to improve the security of Linux servers. Additionally,

there seems to be a desire for a sense of community

even among the distributed Linux administrators in the

organization. Last, the security team needs to try to

approach Linux administrators to help them integrate

into the organization’s overall security strategy. At the

organization studied, the security team is largely

focused on the threats and vulnerabilities facing

Windows servers. This lack of Linux focus by the

security team leaves some Linux administrators feeling

overlooked and underappreciated and could lead to

dangerous levels of non-compliance. The workshop

and increased communications demonstrated the value

for Linux administrators to connect with the security

team. Additionally, it helped show the importance of

embracing security tools that protect the organization.

After the workshop, the cyber lab was instantiated

and made available to participants for four hours to

allow them to use Metasploit to breach a vulnerable

Linux VM. Unfortunately, only 42% of the participants

completed the server breaching exercise following the

workshop. If the lab could have remained running 24/7

for the weeks following the workshop, we believe that

the Linux Server Administrators would have had

significantly more opportunities to use the Metasploit

cyber lab. Unfortunately, due to the cost of running the

scenario in the cloud, it was not deemed possible to run

it continuously. Finally, had the workshop been in-

person as initially planned before the COVID-19

pandemic, it would have been easier to encourage

participation in the cyber lab. The original intention

was to run the workshop and cyber lab as a half-day

event where lunch could also be offered after

completing both. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19

pandemic, the work sites have been closed and remote

training was required.

7 CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated the influence of a focused

SETA workshop on Linux Server Administrators’ use

of cognitive heuristics and biases. Prior to the

workshop, many participants had minimal interaction

with the IT security team. The Linux-focused SETA

workshop brought together server administrators to

help them become aware of the vulnerabilities facing

Linux servers and the risks associated with not

The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’ Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations

39

implementing proper security controls. Additionally,

the workshop introduced participants to the key actions

they can implement and the tools they can use to

protect the organizational Linux servers they manage.

The post-workshop information security updates

provided news about newly identified vulnerabilities,

recent data breaches, and more guidance on how to

implement information security tools discussed in the

workshop. The feedback from participants was

consistently positive. The interaction of the

participants in the new Microsoft Teams channel was

also encouraging. From an organizational perspective,

institutions that have Linux Server Administrators

need to provide SETA that is relevant to Linux as well

as provides the knowledge and tools they need to

improve the information security of the organizational

servers they manage. Additionally, there seems to be a

desire for a sense of community even among the

distributed administrators in the organization. The

questions and advice offered in the Microsoft Teams

channel demonstrated that shared knowledge helped

everyone increase the information security level to the

organizational servers they manage. Anecdotally, we

found that the Linux-focused SETA workshop, and

information security update emails demonstrated the

value for Linux Server Administrators to connect with

the IT security team. Additionally, it helped show the

importance of embracing information security tools

that protect the organization as a whole.

REFERENCES

Antonucci, A. E., Levy, Y., Dringus, L. P., & Snyder, M.

(2021). Experimental study to assess the impact of

timers on user susceptibility to phishing attacks.

Journal of Cybersecurity Education, Research and

Practice, 2, Article 6.

Beuchelt, G. (2017). Securing Web applications, services,

and servers, Vacca, J. R. (Ed.). Computer and

information security handbook (3rd ed., pp. 183-203).

Morgan Kaufmann.

Caballero, A. (2013). Information security essentials for IT

managers: Protecting mission-critical systems. Vacca,

J.R. (Ed.), Computer and Information Security

Handbook (3rd ed., pp. 391-419). Morgan Kaufmann.

Chen, X., Chen, L., & Wu, D. (2018). Factors that influence

employees’ security policy compliance: An awareness-

motivation-capability perspective. Journal of Computer

Information Systems, 58(4), 312-324.

Chen, X., & Tyran, C. K. (2023). A framework for

analyzing and improving ISP compliance. Journal of

Computer Information Systems. https://doi.org/

10.1080/08874417.2022.2161024

Cooper, M., Levy, Y., Wang, L., & Dringus, L. (2021).

Heads-up! An alert and warning system for phishing

emails. Organizational Cybersecurity Journal:

Practice, Process and People, 1(1), 1-22.

https://doi.org/10.1108/OCJ-03-2021-0006

Dang-Pham, D., Pittayachawan, S., & Bruno, V. (2017).

Why employees share information security advice?

Exploring the contributing factors and structural

patterns of security advice sharing in the workplace.

Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 196-206.

Dixon, B. E. (2016). What is health information exchange?

Dixon, B.E. (Ed.), Health Information Exchange:

Navigating and Managing a Network of Health

Information Systems (1st ed.), Academic Press.

Donaldson, S. E., Siegel, S. G., Williams, C. K., & Aslam,

A. (2015). Building an effective defense. Enterprise

cybersecurity: How to build a successful cyber defense

program against advanced threats, Springer, 133-156.

EDURange. (2019). Scenarios. https://edurange.org/

scenarios.html

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (2021). FBI releases

the Internet crime complaint center 2020 Internet crime

report, including COVID-19 scam statistics. https://

www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel/press-releases/fbi-releases-

the-internet-crime-complaint-center-2020-internet-

crime-report-including-covid-19-scam-statistics

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (2022). FBI releases

the Internet Crime Complaint Center 2021 Internet

crime report. https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/

press-releases/fbi-releases-the-internet-crime-complain

t-center-2021-internet-crime-report

Fischer, P., Kastenmüller, A., Greitemeyer, T., Fischer, J.,

Frey, D., & Crelley, D. (2011). Threat and selective

exposure: The moderating role of threat and decision

context on confirmatory information search after

decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

General, 140(1), 51-62.

Flores, W. R., Antonsen, E., & Ekstedt, M. (2014).

Information security knowledge-sharing in

organizations: Investigating the effect of behavioral

information security governance and national culture.

Computers & Security, 43, 90-110.

Gafni, R., & Pavel, T. (2021). Cyberattacks against the

healthcare sectors during the coronavirus era.

Information and Computer Security, 30(1), 137-150.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ICS-05-2021-0059

Gertner, A., Zaromb, F., Roberts, R. D., & Matthews, G.

(2016). The assessment of biases in cognition (MITRE

Technical Report, Case Number 16-0956). https://

www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/publications/pr-16-

0956-the-assessment-of-biases-in-cognition.pdf

Gilovich, T., & Griffin, D. (2013). Introduction – heuristics

and biases: Then and now. Gilovich, T., Griffin, D., and

Kahneman, D. (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: the

psychology of intuitive judgment, Cambridge University

Press, pp. 1-18.

GlobalStats. (2023). Operating system market share

worldwide. https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-

share#monthly-202204-202204-bar

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M.

(2017). A primer on partial least squares structural

equation modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE.

ICISSP 2024 - 10th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

40

Hanus, B., & Wu, Y. (2016). Impact of users’ security

awareness on desktop security behavior: A protection

motivation theory perspective. Information Systems

Management, 33(1), 2-16.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS

path modeling in new technology research: Updated

guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems,

116(1), 2-20.

HIPAA Journal (2022). Summary of 2020-2021 HIPAA

fines and settlements. https://www.hipaajournal.com/

2020-hipaa-violation-cases-and-penalties/

Ifinedo, P. (2012). Understanding information systems

security policy compliance: An integration of the theory

of planned behavior and the protection motivation

theory. Computers & Security, 31(1), 83-95.

Jansen, J., & van Schaik, P. (2018). Persuading end users to

act cautiously online: A fear appeals study on phishing.

Information and Computer Security, 26(3), 264-276.

Kahneman, D. (2011), Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar,

Straus, and Giroux.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural

equation modelling. Guilford Press.

Koch, D. D. (2017). Is the HIPAA security rule enough to

protect electronic personal health information (PHI) in the

cyber age? Journal of Health Care Finance, 43(3), 1-32.

Levy, Y., & Gafni, R. (2021). Introducing the concept of

cybersecurity footprint. Information and Computer

Security, 29(5), 724-736.

Mahalingham, T., McEvoy, P. M., & Clarke, P. J. F. (2023).

Assessing the validity of self-report social media use:

Evidence of No relationship with objective smartphone

use. Computers in Human Behavior, 140, 107567.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107567

Mandiant. (2013). APT1: Exposing one of China's cyber

espionage units. https://www.fireeye.com/content/dam/

fireeye-www/services/pdfs/mandiant-apt1-report.pdf

Moqbel, M. A., & Bartelt, V. L. (2015). Consumer

acceptance of personal cloud: Integrating trust and risk

with the technology acceptance model. AIS

Transactions of Replication Research, 1, 1-11.

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information

Technology. (n.d.). Federal Health IT Strategic Plan:

2015-2020. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/

files/9-5-federalhealthitstratplanfinal_0.pdf

Pachur, T., Hertwig, R., & Steinmann, F. (2012). How do

people judge risks: Availability heuristic, affect heuristic,

or both? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied,

18(3), 314-330.

Pattinson, M., Butavicius, M., Lillie, M., Ciccarello, B.,

Parsons, K., Calic, D., & McCormac, A. (2019).

Matching training to individual learning styles

improves information security awareness. Information

and Computer Security, 28(1), 1-14.

Pollock, T., Levy, Y., Li, W., & Kumar, A. (2021). Subject

matter experts’ feedback on experimental procedures to

measure user’s judgment errors in social engineering

attacks. Journal of Cybersecurity Education, Research

and Practice, 2, Article 4.

Posey, C., Roberts, T., & Lowry, P. B. (2015). The impact

of organizational commitment on insiders’ motivation

to protect organizational information assets. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 32(4), 179–214.

Rhee, H., Ryu, Y. U., & Kim, C. (2012). Unrealistic

optimism on information security management.

Computers & Security, 31(2), 221-232.

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of

fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of

Psychology, 91(1), 93-114.

Rogers, R. W., & Prentice-Dunn, S. (1997). Protection

motivation theory. Gochman, D. S. (Ed.), Handbook of

Health Behavior Research I: Personal and Social

Determinants, Plenum Press, pp. 113-132.

Sadok, M., Alter, S., & Bednar, P. (2020). It is not my job:

exploring the disconnect between corporate security

policies and actual security practices in SMEs.

Information and Computer Security, 28(3), 467-483.

Safa, N. S., & Von Solms, R. (2016). An information

security knowledge-sharing model in organizations.

Computers in Human Behavior, 57(C), 442-451.

Safa, N. S., Von Solms, R., & Furnell, S. (2016),

“Information security policy compliance model in

organizations”, Computers & Security, 56, 70-82.

Sarabadani, J., Crossler, R. E., & D'Arcy, J. (2022). Trading

well-being for ISP compliance: An investigation of the

positive and negative effects of SETA programs.

Proceedings of the 2022 Workshop on Information

Security and Privacy (WISP). https://aisel.aisnet.org/

wisp2022/8

Schroeder, J. (2017). Advanced persistent training: take your

security awareness program to the next level. Springer.

Siponen, M., Mahmood, M. A., & Pahnila, S. (2014).

Employees’ adherence to information security policy:

An exploratory field study. Information &

Management, 51(2), 217-224.

Tsohou, A., Karyda, M., & Kokolakis, S. (2015). Analyzing

the role of cognitive and cultural biases in the

internalization of information security policies:

Recommendations for information security awareness

programs. Computers & Security, 52, 128-141.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for

Civil Rights. (2023). Breach portal: Notice to the

secretary of HHS breach of unsecured protected health

information.

Verizon (2022). The 2022 Data breach investigations report.

https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/reports/dbir

Wash, R., Rader, E., & Fennell, C. (2017). Can people self-

report security accurately? Agreement between self-

report and behavioral measures. Proceedings of the 2017

CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, Association for Computing Machinery (ACM),

2228-2232. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025911

W3Techs. (2023). Usage of operating systems for websites.

https://w3techs.com/technologies/overview/operating_s

ystem/all.

The Role of Heuristics and Biases in Linux Server Administrators’ Information Security Policy Compliance at Healthcare Organizations

41