Curcuma Extract as an Alternative and Safety Pain Reliever for

Geriatric with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta

Analysis

Mohammad Satrio Wicaksono

a

, Clarissa Aulia Pravitha

b

and Hamdi Ramadhan Daulay

c

Faculty of Medicine, Diponegoro University, Semarang, Indonesia

Keywords: Curcuma Extract, Osteoarthritis, Geriatric.

Abstract: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) as pain relievers for osteoarthritis patients that have

several side effects in long-term treatment. Meanwhile based on Global Burden of Disease 2019, about 528

million people have osteoarthritis, which 73% are geriatric patients. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate

the efficacy and safety of curcuma extract compared to NSAIDs in the treatment of geriatric patients with

knee osteoarthritis. This study was made with a systematic literature search method from three databases,

such as PubMed, ScienceDirect, and ProQuest. Inclusion criteria included experimental randomized control

trials and discussed related topics. Mean difference and standard deviation were displayed as the results. With

an I2 value of less than 40%, a fixed-effect model was suggested. For randomized trials, the Cochrane risk-

of-bias tool was used to evaluate the risk of bias (RoB 2). There were a total of 671 participants in five

randomized control trial trials. The pooled mean difference of the VAS score decreased significantly, with a

95% confidence interval (CI) of (-2.97) - (-0.92), P=0.0002, and an I2 of 99%. The I2 data for the KOOS

index indicates 0%, and the pooled mean difference is a significant 2.82 [95% CI: 1.48-4.16, P<0.0001].

NSAID-like medications and curcuma extracts are similar in terms of effectiveness and safety.

1 INTRODUCTION

The most prevalent kind of arthritis worldwide is

called osteoarthritis (OA), affecting around 528

million individuals, 73% of whom are elderly.

(Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network,

2019). More than half of OA patients experience knee

pain, generally called knee osteoarthritis (KOA),

which affects more than 300 million people around

the world (Vos et al., 2016). Globally, the average

yearly indirect expenditures per patient in 2013 were

between $300 and $17,700 (Salmon et al., 2016).

Meanwhile in Indonesia based on Riset Kesehatan

Dasar (Riskesdas) in 2018, the prevalence of joint

diseases including OA in the population over 15 years

old was 7.3% and the percentage of people over 55

years old was 53.15% (Badan Penelitian dan

Pengembangan Kesehatan Kementerian RI, 2018).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6004-9461

b

https://orcid.org/0009-0005-0629-2192

c

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-5694-0769

Multiple risk factors, mechanical stress, and

abnormal joint movement combine to cause OA, an

inflammatory disease that typically manifests as joint

pain and loss of function. Articular cartilage changes

lead to surface fibrillation, irregular cartilage, and

focal erosion (Stewart & Kawcak, 2018). Although

OA is not a deadly disease, previous studies showed

that pain, stiffness, and physical abilities of patients

with OA have impacted in decreasing their quality of

life such as physical, social, and environmental

health. The activities that were often reported as a

problem were using the toilet, walking up the stairs,

and heavy housework (Wojcieszek et al., 2022). Not

only disrupted activities but also OA can impact

mental issues like depressive disorders (Campbell et

al., 2015). Currently, the drugs needed to eliminate

OA are not available.

Therefore, therapies are needed that can manage

symptoms, reduce disease progression, minimize

disability, and improve quality of life. Available

Wicaksono, M. S., Pravitha, C. A. and Daulay, H. R.

Curcuma Extract as an Alternative and Safety Pain Reliever for Geriatric with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis.

DOI: 10.5220/0013666200003873

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Medical Science and Health (ICOMESH 2023), pages 69-77

ISBN: 978-989-758-740-5

Proceedings Copyright © 2025 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

69

therapies are pharmacological, non-pharmacological,

and surgical therapies. For pharmacologic therapy,

according to the IRA Recommendations for

Osteoarthritis, the most common management of OA

can be Analgesic Acetaminophen (paracetamol)

and/or topical and oral NSAIDs (Perhimpunan

Reumatologi Indonesia, 2014). Longterm use of

NSAID drugs will have side effects on the

development of gastric mucosal injury and induced

nephrotoxicity including electrolyte imbalance such

as hyperkalemia (Bindu et al., 2020; Wongrakpanich

et al., 2018). Moreover, in the cardiovascular system,

NSAIDs may be associated with increased blood

pressure by 5 mmHg on average and risk of

congestive heart failure (Wongrakpanich et al.,

2018).

Currently, treatment with the concept of back to

nature where the concept uses herbal ingredients is

widely used by the Indonesian people, especially in

elderly or geriatric patients. Turmeric (Curcuma

longa), is a natural ingredient which very often used

by Indonesians as an herbal treatment and as the main

choice as an adjuvant pharmacological treatment. In

addition to being cheap and easy to obtain, turmeric

(Curcuma longa) has minimal side effects compared

to pharmacological drugs (Mozaffari-Khosravi et al.,

2016).

These natural ingredients can act as anti-

inflammatories by inhibiting inflammatory mediators

such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and PGE2 and reducing pain

in OA patients (Heidari-Beni et al., 2020; Singhal et

al., 2021). The mechanism of treatment with turmeric

(Curcuma longa) has the same goal as

pharmacological treatment, namely reducing

symptoms in geriatric patients with OA. There is a

main compound, curcumin, which is effective in

managing pain in OA patients. The mechanism itself

involves inhibiting the production of COX-2,

phospholipase A2 (cPLA2), and 5-lipoxygenase (5-

LOX); protection of IL-1β which causes chondrocyte

apoptosis; and preventing cartilage degeneration in

joints (Srivastava et al., 2016).

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-

analysis is to examine the safety and efficacy of

treating elderly people with osteoarthritis using

natural components vs NSAIDs.

2 MATERIAL AND METHOD

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic

Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,

which are available at (https://prisma-statement.org/),

served as the foundation for this systematic review.

2.1 Eligibility Criteria

Eligible criteria included in this study were original

research articles or research reports using human

studies with randomized controlled trial design.

Criteria for included studies were determined using

PICO criteria shown in Table 1. Technical reports,

editor answers, scientific posters, study protocols,

conference abstracts, narrative reviews, systematic

reviews, meta-analyses, non-comparative research, in

silico, in vitro, and in vivo investigations were among

the papers that were eliminated. Articles with non-

English, unrelated themes, and full-text availability

issues were also eliminated.

Table 1: PICO Criteria for Included Studies.

Population Geriatric patients with knee

osteoarthritis

Intervention Curcuma extract consumed orall

y

Com

p

arison Placebo and NSAID

Outcome Visual Analog Scale (VAS) and Knee

Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

(KOOS)

2.2 Outcome Measures

The Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

(KOOS) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain ratings

were the outcome measures evaluated in this

systematic review and meta-analysis. Both scoring

methods were applied to quantify the degree of

discomfort associated with osteoarthritis in the knee.

Patients with osteoarthritis utilized the VAS score

to gauge their level of knee discomfort. It has word

descriptions in the range of 0 to 10 (in centimetres),

where "0" denotes "no pain" and "10" denotes

"unbearable or severe pain." The patient filled it out

by checking the boxes for light, moderate, severe, and

no discomfort. (Burckhardt & Dupree Jones, 2003).

KOOS is a self-assessment questionnaire

designed to help people evaluate their own knee

injuries. Five subscales make up the KOOS, and each

is assessed independently: There are nine items

related to pain; seven items to symptoms; seventeen

items related to everyday living; five items related to

sports and leisure; and four things related to quality

of life. There are five alternative answers for each

item, ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (severe). The results

were converted to a 0-100 scale, where 0 denoted

ICOMESH 2023 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MEDICAL SCIENCE AND HEALTH

70

very serious knee issues and 100 denoted no knee

discomfort.

Table 2: Keyword Used in Literature Searching.

Database Ke

y

words

Pubmed ((((((curcuma[MeSH Major Topic]) OR

(Curcuma longa[Title/Abstract])) OR

(turmeric[Title/Abstract])) AND

(geriatric[MeSH Major Topic])) AND

(osteoarthritis[MeSH Major Topic])) OR

(arthritis[Title/Abstract])) OR

(degenerative[Title/Abstract])

ProQuest (Curcuma OR (Curcuma longa) OR

Turmeric AND (Osteoarthritis knee) AND

Geriatric)

Science

Direct

(Curcuma OR “Curcuma longa” OR

Turmeric) AND (Geriatric) AND

(Osteoarthritis OR Arthritis OR

Degenerative)

2.3 Data Source and Search

Acquired studies have been collected using searching

databases, such as PubMed, ProQuest, and Science

Direct. The search was conducted from the inception

of the database until December 2022. The keywords

used were using Boolean operator and mesh in each

database which can be seen in Table 2. The studies

are stored in the authors’ library using the Mendeley

group reference manager.

2.4 Selection Process

After searching keywords written in Table 2, we used

article type filters on each database to exclude the

non-RCT articles. Results from 3 databases were later

combined and screened by three independent

reviewers through title, year of publication, and DOIs

for duplicate removal. After duplicate removal,

studies were later screened through abstract and full

paper for irrelevance removal. The PRISMA flow

chart contained records of the study selection

procedures.

2.5 Data Collection Process

Studies after final screening are extracted for the

relevant data and recorded in Google Spreadsheet.

The recorded data were: (1) first author, year, (2)

country, (3) sample size, (4) gender, (5) mean age, (6)

name of intervention, length of intervention,

comparison, and (7) outcome that consist of VAS

score and KOOS index. All statistical tests for this

meta-analysis were conducted using Review

Manager (RevMan) v5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration,

UK).

2.6 Study Risk of Bias Assessment

(Quantitative Synthesis)

The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials

(RoB 2), which is available at

(https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-

revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials),

was used by three independent reviewers to evaluate

each research that was included in this investigation.

Later, the disparate conclusions made by reviewers

were reviewed and settled among themselves.

2.7 Quantitative Data Synthesis

(Meta-Analysis)

In this review, data on Mean Difference (MD) and

Standard Deviation (SD) were computed. When the

included studies were deemed homogeneous (little

variability in study findings or variance owing to

random error), as shown by an I2 value of less than

40%, a fixed-effect model (FEM) was applied. If not,

a random-effect model (REM) was employed. A

forest plot was used to display the pooled estimate.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study Selection

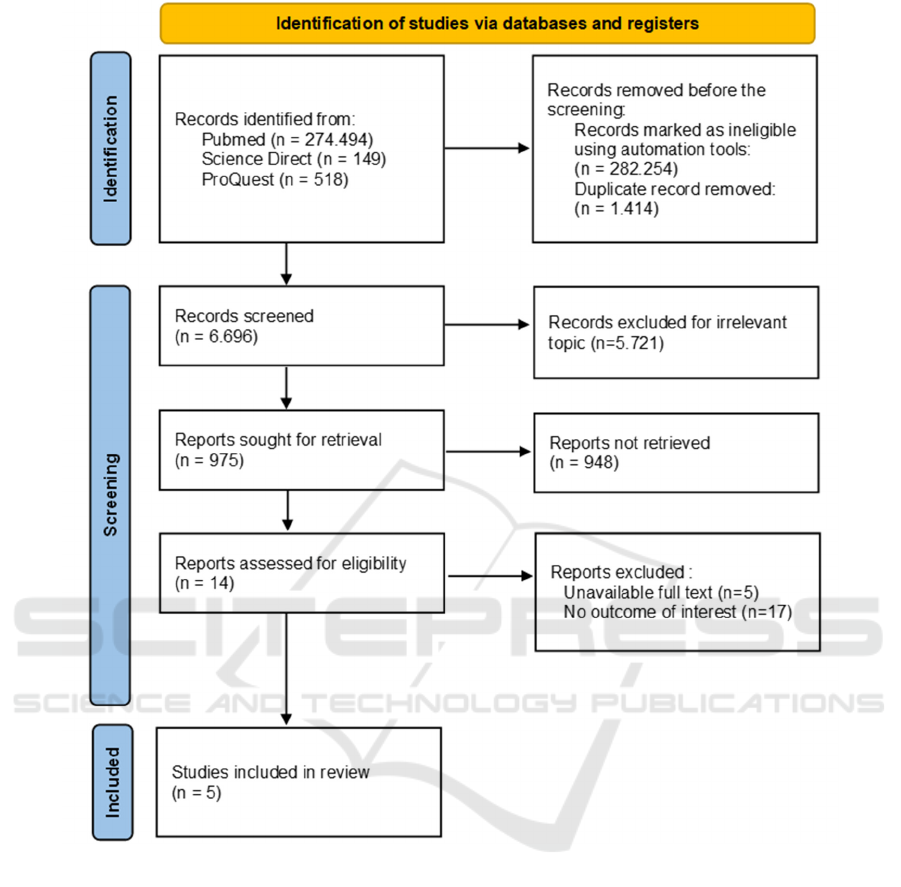

After conducting literature searching from 3

databases which are PubMed, ProQuest, and

ScienceDirect, 290.368 studies were generated.

Automation tools from each database were used to

exclude non-RCT studies, resulting in 282.254

articles being excluded. Then, 1.414 were removed

due to duplicate articles. Later, authors assessed all of

the remaining articles from the title and abstract for

irrelevance to the topic, resulting in 6.669 articles

excluded. 5 articles were then excluded for the

unavailable full-text availability. Lastly, the author

assessed eligibility for all the studies and agreed to

exclude 17 studies because of an unpresent outcome

of interest. Five papers were included in this study for

the meta-analysis and systematic review. Figure 1

shows the flow chart of the PRISMA diagram used to

select our studies.

Curcuma Extract as an Alternative and Safety Pain Reliever for Geriatric with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis

71

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 Flow Diagram

3.2 Study Characteristic

From the five studies included in this review, the total

number of participants is 671 participants. Most of

the studies (n=5) observed the elderly participants for

their studies, but only 1 study from Henrotin et al,

researched geriatric (> 60-year-old) patients. The rest

of the included studies were approached 60 years of

age for their participants. The study characteristics

are shown in Table 3.

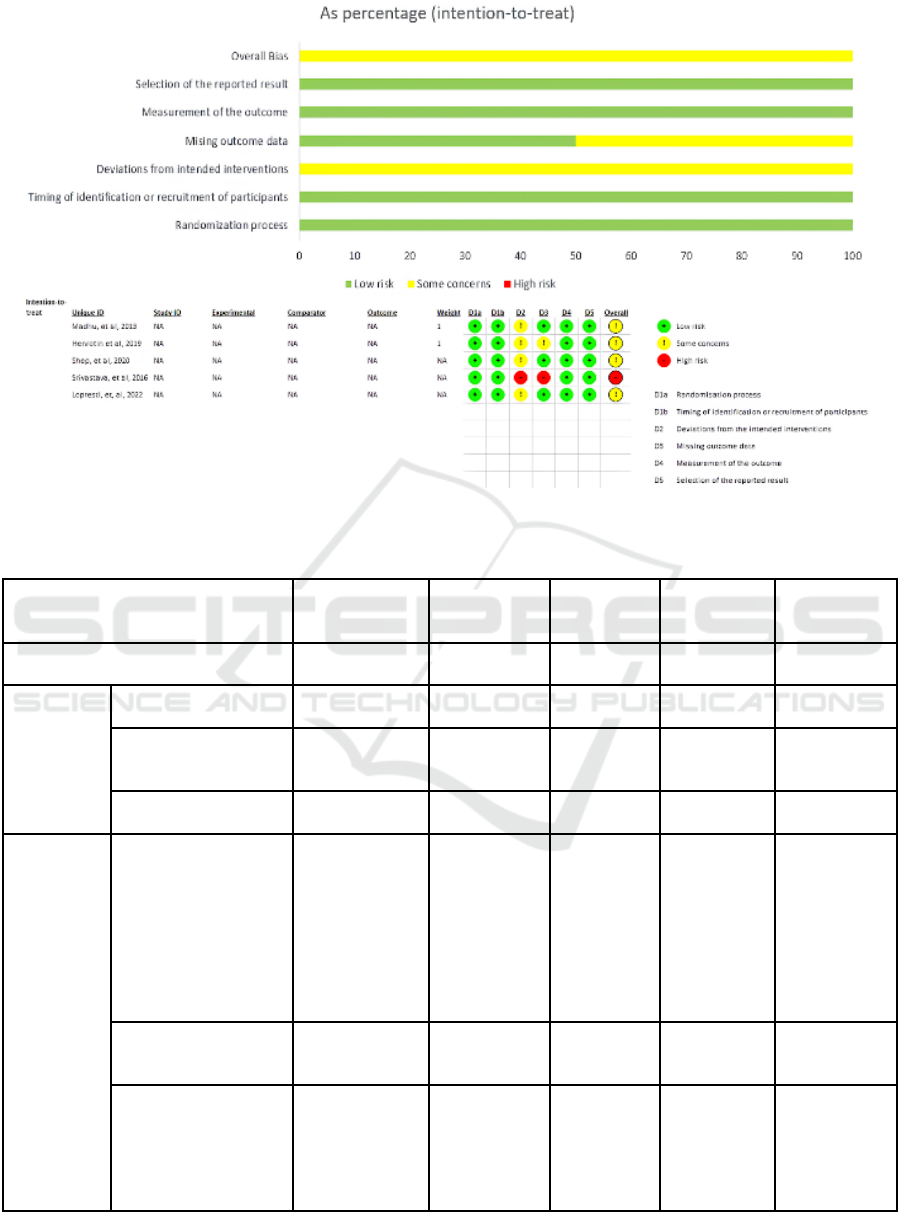

3.3 Risk of Bias in Studies

To assess the quality of each study, the Cochrane risk-

of-bias instrument for randomized trials (RoB 2) was

utilized. One study showed a high risk of bias

(Srivastava et al) because there is a bias due to the

intended intervention being balanced between groups

and missing outcome data causing participants lost to

follow-up. Four studies showed some concern (Shep

et al, Madhu et al. al, Henrontin et. al, Lopresti et. al)

because there is an intended intervention as a rescue

medication in each trial group. The risk of bias is

summarized in Figure 2.

ICOMESH 2023 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MEDICAL SCIENCE AND HEALTH

72

Figure 2: Risk of Bias Assessment Result

Table 3: Characteristic of Studies.

Author, Year

Madhu, et al,

2013

17

Srivastava, et

al, 2016

14

Lopresti, et

al. 2022

18

Shep, et al,

2020

19

Henrotin, et al.

2019

20

Countr

y

India India Australia India Bel

g

iu

m

Population

Sam

p

le size 120 160 101 140 150

Sex Female and Male

Female and

Male

Female and

Male

Female and

Male

Female and

Male

Mean A

g

e 57 50 58 52 60

Intervention

Name of intervention

1 capsule

(500mg)

curcuma extract

Curcuma

extract

500mg/capsule

with

Diclofenac 50

mg/capsule

1 capsule

(500 mg)

curcumin

extract

1 capsule

(500 mg)

curcuminoid

complex

(BCM-95)

and 1 capsule

(50 mg)

diclofenac

Bio-optimised

Curcuma

longa (BCL)

extract (500

mg/capsule)

Length of

intervention

42 days 4 months 2 months 28 days 3 months

Comparison

1 capsule

(400mg) Placebo

(Microcrystalline

cellulose)

Placebo

500mg/capsule

with

Diclofenac 50

m

g

/ca

p

sule

1 capsule

(500mg)

placebo

1 capsule (50

mg)

Diclofenac

Placebo

Curcuma Extract as an Alternative and Safety Pain Reliever for Geriatric with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis

73

Outcome

VAS

Control

Before = 6.15 ±

1.37

After = 4.60 ±

2.08

Before = 7.66

± 0.14

After = 5.11 ±

0.14

N/A

Before =

7.81±0.73

After =

5.61±0.61

N/A

Intervention

Before = 6.65 ±

2.1

After = 1.95 ±

1.78

Before = 7.94

± 0.13

After = 4.03 ±

0.08

N/A

Before =

7.90±0.64

After =

3.32±0.60

N/A

p

-value P < 0.05 P < 0.05 N/A P < 0.001 N/A

KOOS

Control N/A N/A

Before =

61.17 ±

13.65

After = 66.69

± 16.66

Before =

51.58 ± 5.49

After =

90.38±3.61

Before = 44.2

± 13.9

After = 55 ±

16.5

Intervention N/A N/A

Before =

60.08 ± 12

After = 72.66

± 16.77

Before =

53.15±4.24

After = 93.03

± 4.75

Before = 45.8

± 15.6

After = 58.6 ±

18.4

p

-value N/A N/A P = 0.009 P < 0.001 P <

0.001

Abbreviation list

VAS, Visual Analog Scale; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; N/A, not

available

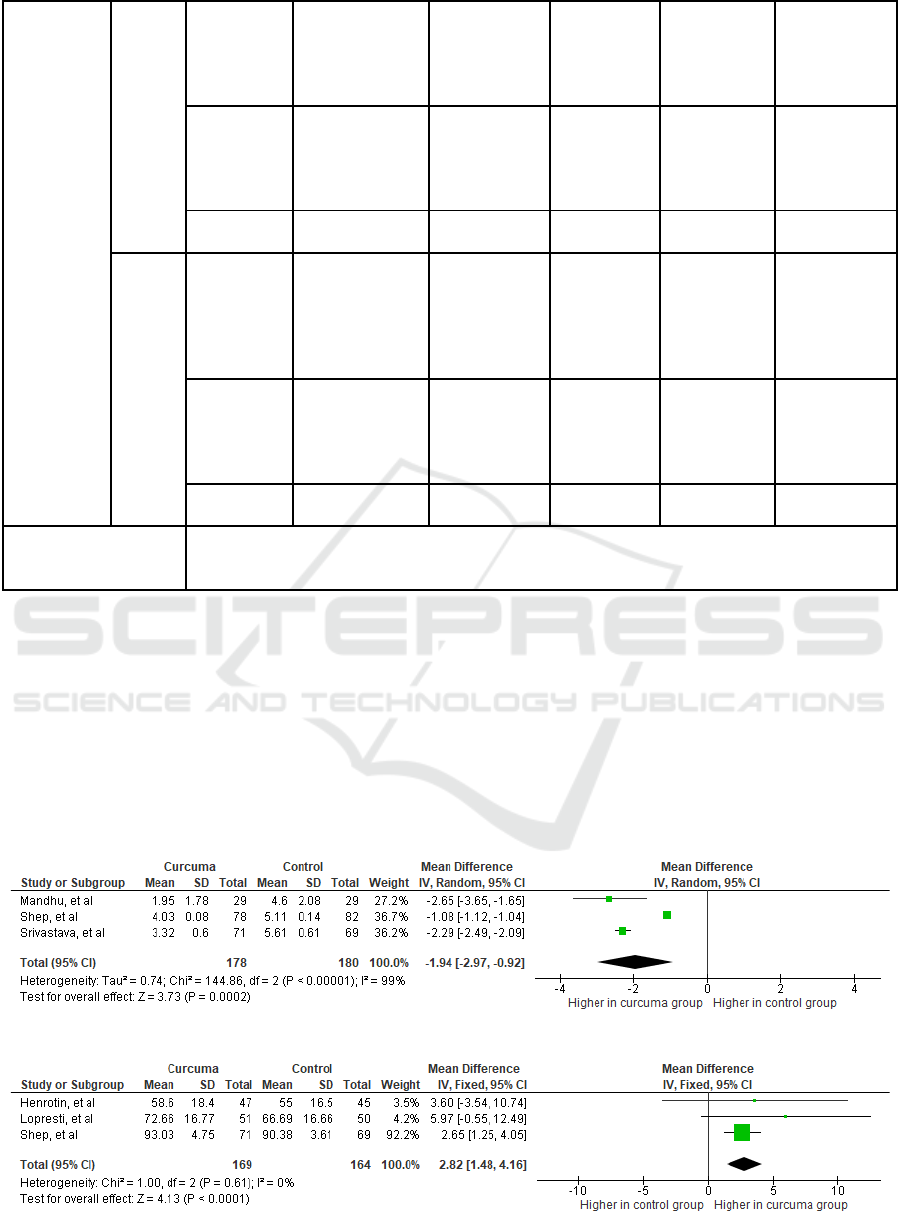

3.4 Meta Analysis

Review Manager (RevMan) v5.4 (Cochrane

Collaboration, UK) was used to conduct the statistical

analysis. In this review, the Mean Difference (MD)

and Standard Deviation (SD) were then computed

with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI). The data was

then processed into pooled standardized mean

difference forest plot form. Our study assessed

extractable quantitative data and grouped them into 2

outcomes which include VAS Score and KOOS

Index. The forest plot of the meta-analysis can be

seen in Figure 3-4.

A total of 5 studies with 671 participants of knee

osteoarthritis patients, dominated by elderly patients

>50 years old. Two included studies have VAS score

outcomes, two included studies have KOOS index

outcomes, and one study has VAS and KOOS

outcomes that are analysed in this review.

Figure 3: VAS Score.

Figure 4: KOOS Index.

ICOMESH 2023 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MEDICAL SCIENCE AND HEALTH

74

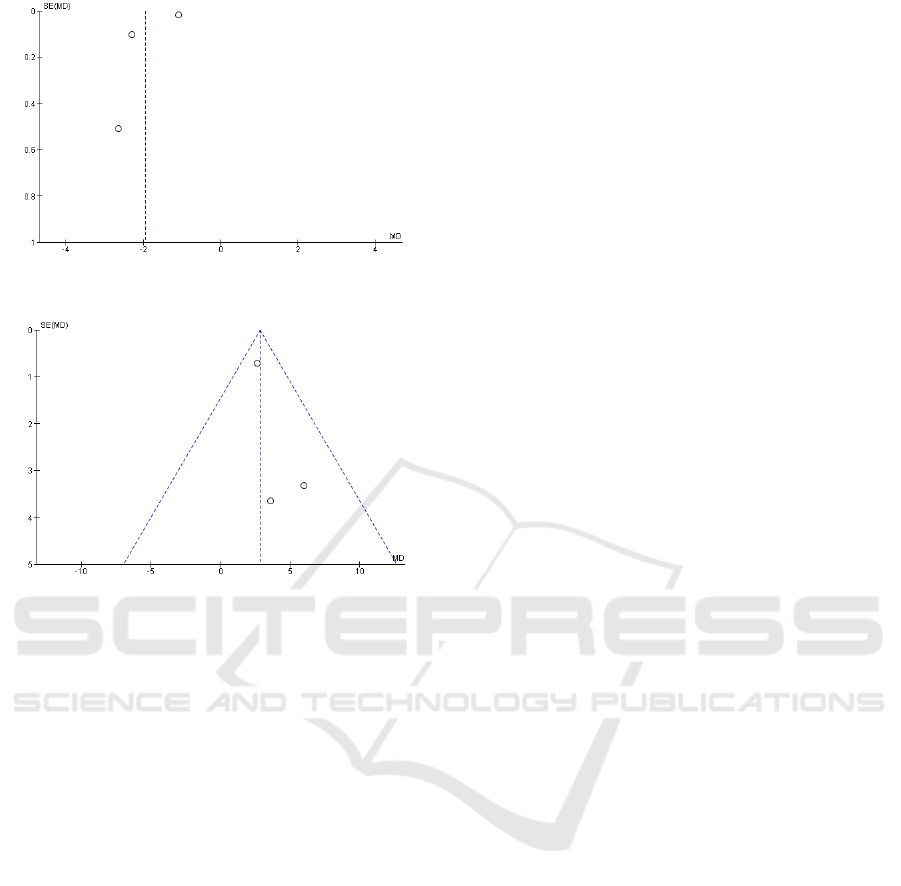

Figure 5: Funnel Plot of VAS Score.

Figure 6: Funnel Plot of KOOS Index.

4 DISCUSSIONS

4.1 Curcuma Extract Improves Knee

Pain on Knee Osteoarthritis

As a result of cartilage damage, osteoarthritis (OA) is

an inflammatory disease that mostly manifests as

joint discomfort and loss of joint function. Damage to

the collagen matrix triggers chondrocyte proliferation

and the production of hypertrophic chondrocyte cell

clusters, which in turn promote the growth of ossified

cartilage and the development of osteophytes

(Stewart & Kawcak, 2018; Dobson et al., 2018; Loef

et al., 2019). Increases in matrix metalloproteinase

(MMP) and inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and

IL-1β are linked to this damage. Nitric oxide and

reactive oxygen species (ROS) will rise as a result,

leading to an increase in oxidative stress and

worsening symptoms of joint inflammation (Sohn et

al., 2012). Therefore, a treatment that acts as a good

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant is needed to

reduce pain and inflammation in geriatric patients

with OA.

Curcuma extract has been shown to improve knee

pain using VAS score on geriatric patients with knee

osteoarthritis with a significant pooled mean

difference (MD) of -1.94 [95% CI: (-2.97) - (-0.92),

P = 0.0002] with I

2

showing 99%. Heterogenous

results because there are 2 studies from Srivastava et

al. and Shep et al. that use Diclofenac in both groups

can produce biased results. Different formulations for

curcuma extract also can induce bias in the study.

Furthermore, curcuma extract has been shown to

improve knee pain using the KOOS index with a

significant pooled mean difference (MD) of 2.82

[95% CI: 1.48 - 4.16, P<0.0001] with I

2

showing 0%.

The components of curcuma extract include

phenolic pigments (which contain the active

ingredient curcumin, which acts as an anti-

inflammatory agent), essential oils (such as cineole,

linalool, α-terpinene, caryophyllene, ar-curcumene,

zingiberen, curcumol, DL-turmerone, arturmerone,

and dehydrocurdione), cholesterol, fatty acids,

potassium, sodium, magnesium, calcium, manganese,

iron, copper, and zinc, among other elements)

(Karlowicz-Bodalska et al., 2017). The pain

improvement in knee osteoarthritis was facilitated by

the anti-inflammatory of curcuma extract that inhibits

TNF-α, IL-1β, and PGE2. Curcumin, the main

ingredient in curcuma extract, can reduce pain by

inhibiting the production of COX-2 which produces

the pain sensation (Srivastava et al., 2016).

The combination of curcuma and other NSAID

medication can improve better outcomes compared

with NSAID alone. Studies are being conducted to

assess if curcuma extract is more effective as an

adjuvant treatment for OA-related pain than NSAIDs

alone. As seen from the VAS score data before and

after treatment, the intervention group receiving a

combination of curcuma and NSAID has a lower

VAS score after treatment than just giving the NSAID

alone (Shep et al., 2020; Srivastava et al., 2016).

4.2 Safety of Curcuma Extract

In some studies, curcuma extract has fewer adverse

effects, such as dyspepsia, diarrhea, other

gastrointestinal symptoms, and musculoskeletal

symptoms compared to the placebo (Srivastava et al.,

2016; Wang et al., 2020). In some OA cases, 6.6% of

patients treated with curcuma exhibited the least

number of adverse effects during the intervention

period (Madhu et al., 2013). When curcuminoid

complex is added to diclofenac as an adjuvant

treatment, it helps to lessen the GI adverse effects

caused by the drug and lessens the need for H2

blockers (Lopresti et al., 2021).

Curcuma extract as an alternative to NSAIDs in

patients with osteoarthritis which mostly has adverse

Curcuma Extract as an Alternative and Safety Pain Reliever for Geriatric with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis

75

effects that are mild and transient (Lopresti et al.,

2021). From a pharmacological perspective,

curcumin is a full choleretic-cholagamic agent.

Because they compress the gallbladder, the curcumin

cleavage products (ferulic and hydrofluoric acids)

have cholecystokinin characteristics. On the other

hand, paratholil methyl carbinol, another major

component, has potent choleretic action. The

choleretic action of curcumin causes a 62% rise in

bile output (Shep et al., 2020). Despite the negative

effects of curcumin extract, blood reports for liver,

kidney, and complete blood counts did not

significantly alter before or after the research drugs

were taken (Henrotin et al., 2019).

4.3 Strengths and Limitations

The effectiveness of curcuma extract on elderly

individuals with osteoarthritis in the knee is the

subject of the first systematic review and meta-

analysis conducted on this subject. This systematic

review assessed the curcuma therapy effect that were

consumed orally to reduce osteoarthritis pain in the

elderly age. All studies included are randomized

controlled trials with significant results in pain score

by VAS score and KOOS index.

Nonetheless, this study is not without limitations.

The studies that were included have a high and

moderate risk of bias. The heterogeneity in the

included studies is the different formulations but still

given orally. Also, the use of other medications

combined with curcuma extract, such as NSAID, can

cause bias in the study result. Study duration can be

the limitation of included studies because curcuma

can’t work significantly in a short time duration.

Other factors, such as the severity and type of

osteoarthritis are not discussed in including studies.

There might be a possibility of missing some

important information in studies written in other

languages than English or Indonesian. Irretrievable

full-text is also the limitation of this study. We

suggest conducting more randomized control studies

with a bigger sample size to notice more about the

safety and efficacy of curcuma extract therapy and to

optimize the impact of curcuma extract.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The use of curcuma extract is a potential treatment for

knee osteoarthritis in elderly people, according to this

systematic review and meta-analysis. It has been

shown that curcuma extract is quantitatively

significant in improving knee pain in osteoarthritis

using the VAS score and KOOS index.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Every author stated that there are no conflicting

interests in this research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to express gratitude for the

lecturers and supervisor of our team, particularly dr.

Ghana Adyaksa, M.Si.Med, Sp.OT and dr. Desy

Armalina, M.Si.Med for the great advices.

REFERENCES

Badan Penelitian dan Pengembangan Kesehatan

Kementerian RI. (2018). Riset Kesehatan Dasar

(Riskesdas) 2018. Kementerian Kesehatan Republik

Indonesia.

Bindu, S., Mazumder, S., & Bandyopadhyay, U. (2020).

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and

organ damage: A current perspective. Biochemical

Pharmacology, 180, 114147.

Burckhardt, C., & Dupree Jones, K. (2003). Adult measures

of pain: The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ),

Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain Scale (RAPS), Short-Form

McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Verbal

Descriptive Scale (VDS), Visual Analog Scale (VAS),

and West Haven-Yale Multidisciplinary Pain Inventory

(WHYMPI). Arthritis Care & Research, 49, S96–S104.

Campbell, C. M., Buenaver, L. F., Finan, P., Bounds, S. C.,

Redding, M., McCauley, L., Robinson, M., Edwards, R.

R., & Smith, M. T. (2015). Sleep, Pain Catastrophizing,

and Central Sensitization in Knee Osteoarthritis

Patients With and Without Insomnia. Arthritis Care &

Research, 67(10), 1387–1396.

Dobson, G. P., Letson, H. L., Grant, A., McEwen, P.,

Hazratwala, K., Wilkinson, M., & Morris, J. L. (2018).

Defining the osteoarthritis patient: Back to the future.

Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 26(8), 1003–1007.

Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019)

Results, Global Burden of Disease Collaborative

Network (2019)

Heidari-Beni, M., Moravejolahkami, A. R., Gorgian, P.,

Askari, G., Tarrahi, M. J., & Bahreini-Esfahani, N.

(2020). Herbal formulation “turmeric extract, black

pepper, and ginger” versus Naproxen for chronic knee

osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, controlled

clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research: PTR, 34(8),

2067–2073.

Henrotin, Y., Malaise, M., Wittoek, R., de Vlam, K.,

Brasseur, J.-P., Luyten, F. P., Jiangang, Q., Van den

Berghe, M., Uhoda, R., Bentin, J., De Vroey, T.,

ICOMESH 2023 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MEDICAL SCIENCE AND HEALTH

76

Erpicum, L., Donneau, A. F., & Dierckxsens, Y.

(2019). Bio-optimized Curcuma longa extract is

efficient on knee osteoarthritis pain: A double-blind

multicenter randomized placebo controlled three-arm

study. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 21(1), 179.

Karlowicz-Bodalska, K., Han, S., Freier, J., Smolenski, M.,

& Bodalska, A. (2017). CURCUMA LONGA AS

MEDICINAL HERB IN THE TREATMENT OF

DIABET- IC COMPLICATIONS. Acta Poloniae

Pharmaceutica, 74(2), 605–610.

Loef, M., Schoones, J. W., Kloppenburg, M., & Ioan-

Facsinay, A. (2019). Fatty acids and osteoarthritis:

Different types, different effects. Joint Bone Spine,

86(4), 451–458.

Lopresti, A. L., Smith, S. J., Jackson-Michel, S., &

Fairchild, T. (2021). An Investigation into the Effects

of a Curcumin Extract (Curcugen®) on Osteoarthritis

Pain of the Knee: A Randomised, Double-Blind,

Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients, 14(1), 41.

Madhu, K., Chanda, K., & Saji, M. J. (2013). Safety and

efficacy of Curcuma longa extract in the treatment of

painful knee osteoarthritis: A randomized placebo-

controlled trial. Inflammopharmacology, 21(2), 129–

136.

Mozaffari-Khosravi, H., Naderi, Z., Dehghan, A.,

Nadjarzadeh, A., & Fallah Huseini, H. (2016). Effect of

Ginger Supplementation on Proinflammatory

Cytokines in Older Patients with Osteoarthritis:

Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial.

Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics,

35(3), 209–218.

Perhimpunan Reumatologi Indonesia. (2014).

Rekomendasi IRA untuk Diagnosis dan

Penatalaksanaan Osteoartritis. Divisi Reumatologi

Departemen Ilmu Penyakit Dalam FKUI/RSCM.

Roos, E. M., Roos, H. P., Lohmander, L. S., Ekdahl, C., &

Beynnon, B. D. (1998). Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis

Outcome Score (KOOS)—Development of a self-

administered outcome measure. The Journal of

Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 28(2), 88–

96.

Salmon, J. H., Rat, A. C., Sellam, J., Michel, M., Eschard,

J. P., Guillemin, F., Jolly, D., & Fautrel, B. (2016).

Economic impact of lower-limb osteoarthritis

worldwide: A systematic review of cost-of-illness

studies. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 24(9), 1500–1508.

Shep, D., Khanwelkar, C., Gade, P., & Karad, S. (2020).

Efficacy and safety of combination of curcuminoid

complex and diclofenac versus diclofenac in knee

osteoarthritis: A randomized trial. Medicine, 99(16)

Singhal, S., Hasan, N., Nirmal, K., Chawla, R., Chawla, S.,

Kalra, B. S., & Dhal, A. (2021). Bioavailable turmeric

extract for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, non-

inferiority trial versus paracetamol. Trials, 22(1), 105.

Sohn, D. H., Sokolove, J., Sharpe, O., Erhart, J. C.,

Chandra, P. E., Lahey, L. J., Lindstrom, T. M., Hwang,

I., Boyer, K. A., Andriacchi, T. P., & Robinson, W. H.

(2012). Plasma proteins present in osteoarthritic

synovial fluid can stimulate cytokine production via

Toll-like receptor 4. Arthritis Research & Therapy,

14(1), R7. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3555

Srivastava, S., Saksena, A. K., Khattri, S., Kumar, S., &

Dagur, R. S. (2016). Curcuma longa extract reduces

inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers in

osteoarthritis of knee: A four-month, double-blind,

randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Inflammopharmacology, 24(6), 377–388.

Stewart, H. L., & Kawcak, C. E. (2018). The Importance of

Subchondral Bone in the Pathophysiology of

Osteoarthritis. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, 178.

Vos, T., Allen, C., Arora, M., Barber, R., Bhutta, Z., Brown,

A., Carter, A., Casey, D., Charlson, F., Chen, A.,

Coggeshall, M., Cornaby, L., Dicker, D., Dilegge, T.,

Erskine, H., Ferrari, A., Fitzmaurice, C., Fleming, T., &

Murray, C. (2016). Global, regional, and national

incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability

for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic

analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.

The Lancet, 388, 1545–1602.

Wang, Z., Jones, G., Winzenberg, T., Cai, G., Laslett, L. L.,

Aitken, D., Hopper, I., Singh, A., Jones, R., Fripp, J.,

Ding, C., & Antony, B. (2020). Effectiveness of

Curcuma longa Extract for the Treatment of Symptoms

and Effusion-Synovitis of Knee Osteoarthritis: A

Randomized Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine,

173(11), 861–869.

Wojcieszek, A., Kurowska, A., Majda, A., Liszka, H., &

Gądek, A. (2022). The Impact of Chronic Pain,

Stiffness and Difficulties in Performing Daily

Activities on the Quality of Life of Older Patients with

Knee Osteoarthritis. International Journal of

Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24),

16815.

Wongrakpanich, S., Wongrakpanich, A., Melhado, K., &

Rangaswami, J. (2018). A Comprehensive Review of

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use in The

Elderly. Aging and Disease, 9(1), 143–150.

Curcuma Extract as an Alternative and Safety Pain Reliever for Geriatric with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis

77