Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the Impact of Educational Input

on Economic Growth in the EU

Yubo He

Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, U.K.

Keywords: Government Expenditure, Teaching Staff, Education Spending, GDP, EU Countries.

Abstract: This research examines the relationship between government spending on education and economic growth

across EU countries from 2010-2020. The study aims to assess whether educational resourcing inputs

correlate with economic outputs. The hypothesis is that government expenditure and teaching staff at all levels

positively affect gross domestic product(GDP) growth. Quantitative multivariate analysis techniques,

including correlation analysis, regression modelling, and autoregressive integrated moving average(ARIMA)

time series analysis, were applied to test these associations. The panel dataset comprised spending, staffing

and GDP data for 16 countries over 11 years. Results showed a moderate positive correlation between

education spending and GDP over time. Regression analysis found spending and secondary teaching staff as

significant positive predictors of GDP, explaining 95.8% of the variation.ARIMA models revealed spending

as relatively stable with short-term fluctuations. While these results demonstrate essential connections

between resources and growth, ongoing analysis should incorporate additional educational inputs, account for

country-specific factors, and test more complex relationships. This can provide greater insight into the

dynamics between targeted investments in quality, equitably distributed education and the resilience of human

capital and economies. Further research building on these initial findings can help guide policy decisions on

education budgets.

1 INTRODUCTION

Education is a key driver of economic growth by

enhancing human capital through individuals'

knowledge, skills, and capacities (Toader et al 2018).

As such, government prioritization of education

resourcing and policy is closely tied to

macroeconomic outcomes. This research aims to

elucidate the relationship between educational inputs

and economic outputs in EU countries over the past

decade, as increasing productivity and resilience

continues as a policy priority amidst recent shocks.

The study examines two key educational input

factors - government expenditure on education as a

percentage of GDP and the number of teaching staff

at the primary, secondary, and tertiary levels. The

output variable is GDP in 2020. Correlation,

regression, and ARIMA time series modeling

techniques assess associations between spending,

staffing, and GDP from 2010-2020 across EU

member states. This quantitative multivariate analysis

can provide insights to help strengthen education

policy planning and investments.

Specifically, the research explores the complex

two-way interplay between education and economics.

While schooling and human capital investments are

expected to produce growth dividends,

macroeconomic conditions also shape spending

priorities and resource allocation (OECD 2022). This

study aims to unpack these dynamics in the EU

context. Findings can inform policymakers on

optimizing education financing for economic

development and resilience.

The recent COVID-19 shock further underscores

the need for evidence-based investments. Pandemic

disruptions to education systems could impact human

capital with GDP consequences (Pietro et al 2020).

Analyzing pre-pandemic spending patterns provides

context on buffers and flexibility as countries rebuild.

Links between education inputs and outputs highlight

policy levers for growth.

On the input side, the study focuses on public

expenditures, as over 90% of education funding in EU

countries comes from government sources (Eurydice

2020). With competing budget priorities, insight into

the growth return on spending can guide efficient

142

He, Y.

Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the Impact of Educational Input on Economic Growth in the EU.

DOI: 10.5220/0012801500003885

Paper published under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Data Analysis and Machine Learning (DAML 2023), pages 142-148

ISBN: 978-989-758-705-4

Proceedings Copyright © 2024 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda.

resource allocation. Meanwhile, teacher quantity and

quality are assessed using staff numbers, as teacher

policies shape instructional inputs into developing

human capital (European Commission's Directorate

2023).

This research focuses specifically on the EU

context. As an integrated economic union, education

and economic policy in member states have regional

implications (Gornitzka 2018). Analyzing spending

and staffing relationships with GDP can highlight

needs and priorities for collaboration. Findings may

reveal convergence or divergence in education

investments and outputs.

Methodologically, the study applies quantitative

multivariate techniques well-suited to modeling

complex linkages between multiple variables over

time. Correlation and regression analyses assess the

strength of connections and predictive relationships

(Creswell and Creswell 2017). ARIMA time series

modeling provides a nuanced understanding of

spending trends and dynamics (Chatfield and Xing

2019).

By leveraging these rigorous statistical methods,

the analysis aims to uncover subtle patterns in the

data. Testing hypothesized associations and

forecasting future investment scenarios can inform

evidence-based policy development. Education

quality and institutional factors mediate input-output

relationships, warranting ongoing analysis (Eric and

Ludger 2023).

Human capital investments for regional

development and shared prosperity at the EU level

aligned with the blocs' strategic priorities (European

Commission 2021). It is necessary for coordinated

efforts to improve education access, quality, and

relevance across member states. Education fuels

mobility, productivity, and growth regionally in the

context of economic integration (OECD 2022).

The research questions addressed include: 1) How

do education spending and staffing correlate with

GDP over time and between countries? 2) Which

inputs show the strongest statistical relationships with

economic growth? 3) What patterns and trends exist

in government prioritization of education budgets?

The study tests hypothesized positive links between

spending, teachers, and GDP. Findings aim to inform

strategic investments and reforms for human capital

development.

2 METHOD

2.1 Research Design

This study utilizes a quantitative correlational research

design to examine the relationships between education

inputs and economic outputs in the EU context. This

non-experimental design is appropriate for assessing

and modeling associations between naturally

occurring variables rather than testing controlled

interventions (Seeram 2019). The aim is not to

establish causal claims but rather to characterize

relationships' strength, directionality, and predictive

capacity in the observational data.

The retrospective panel data structure enables

cross-sectional comparisons between countries and

time series analysis of spending trends over 2010-

2020 (Gujarati 2022). This supports correlating

current GDP with past inputs to model potential lag

effects, as the impact of education investments on

growth can manifest over the years. The study is

observational rather than experimental - no variables

are manipulated.

2.2 Sample

The study sample includes 27 EU member states with

complete data from 2010-2020. This panel data

structure enables time series analysis of trends and

comparisons between countries. The 11-year

retrospective view provides sufficient data points for

multivariate statistical analysis while focusing on the

most recent decade.

2.3 Data Collection

Secondary datasets were compiled from public

international databases. Government education

expenditure data comes from the World Bank

Databank. Teaching staff and GDP data were

downloaded from the United Nations Data repository.

Utilizing high-quality, comparable indicators from

reputable sources enhances validity and reliability.

2.4 Variables

• Independent variables: Government education

expenditure as a percentage of GDP, number

of teaching staff at the primary, secondary, and

tertiary levels.

• Dependent variable: GDP level in 2020

• Control variables: Country, year

Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the Impact of Educational Input on Economic Growth in the EU

143

2.5 Analysis Methods

• Descriptive statistics to characterize inputs,

outputs, distributions, and trends

• Correlation analysis to assess bivariate

relationships between inputs and outputs

• Multiple regression modeling to evaluate the

relative predictive strength of inputs on GDP

• ARIMA time series analysis to model spending

trends and dynamics

• Visualizations, including scatterplots,

heatmaps, and time series plots to illustrate

results

Combining correlation, regression, and time series

techniques provides a robust multivariate analysis

approach. Diagnostic checks help ensure assumptions

are met. Sensitivity analysis informs the reliability and

generalizability of insights.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The analysis generated key findings regarding the

relationships between educational inputs and

economic outputs in EU countries from 2010-2020.

This section will present the results of the correlation,

regression, and ARIMA time series modeling,

summarizing key insights from each technique. The

implications of the quantitative findings will then be

discussed about the research questions on connections

between education spending, staffing, and GDP

growth. Limitations and future research needs will

also be considered. The multivariate modeling reveals

nuanced dynamics, emphasizing the importance of

sustained, quality investments tailored to national

contexts. The discussion will synthesize results across

methods to highlight policy-relevant relationships for

strategically strengthening human capital

development and economic growth.

3.1 Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 shows the descriptive summary of government

spending, teaching staff, and the 2020 GDP. The

summary statistics for government education

expenditure as a percentage of GDP from 2010 to 2020

provide an overview of spending trends across EU

countries. On average, spending increased slightly

from 5.315% in 2010 to 5.193% in 2020, indicating a

small positive trend over the decade. However,

Kirkness (2022) notes substantial variation between

countries, with minimums of around 3% and

maximums of over 7% of GDP spent on education

(Kirkness 2023). This aligns with the European

Commission's (2021) analysis highlighting differences

in education budgets between EU members.

While ranges fluctuate, the interquartile spending

remains fairly consistent over time, suggesting a right-

skewed but stable distribution. As Martin et al. (2018)

discuss, most EU countries target between 4-6% of

GDP for public education spending each year. The

summary statistics corroborate this general pattern

without dramatic changes or fluctuations annually in

the aggregate (OECD 2022).

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for government spending, teaching staff, and 2022 GDP.

Minimum 1st Quarter Median Mean 3rd Quarter Maximum

Spending

2010 3.49 4.53 5.30 5.32 5.88 8.56

2011 3.06 4.50 5.11 5.25 5.71 8.49

2012 2.96 4.35 4.95 5.16 5.83 7.54

2013 3.05 4.27 4.97 5.32 6.02 8.49

2014 3.12 4.30 4.94 5.17 5.49 7.64

2015 3.11 4.26 4.91 5.04 5.46 7.44

2016 2.98 3.99 4.77 4.94 5.48 7.62

2017 3.10 3.90 4.61 4.78 5.27 7.75

2018 3.35 4.01 4.62 4.79 5.24 7.64

2019 3.30 4.15 4.63 4.81 5.23 7.64

2020 3.10 4.60 5.08 5.19 5.88 7.17

Teaching Staff

Primary 12.00 38.50 122.00 268.90 268.00 1026.00

Secondary 18.00 81.00 238.00 472.00 440.50 2363.00

Tertiary 5.00 33.50 121.00 220.60 177.50 1037.00

2022 GDP 14911 63546 245349 566378 531462 3846414

DAML 2023 - International Conference on Data Analysis and Machine Learning

144

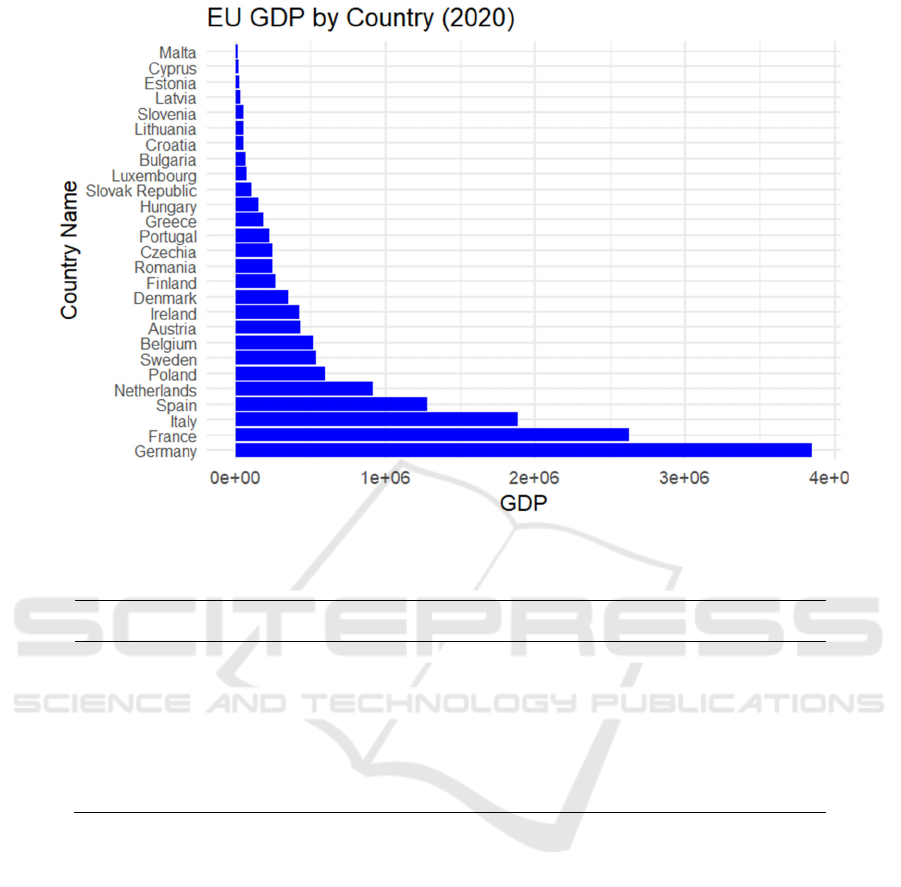

Figure 1: EU GDP bar char (Photo/Picture credit: Original).

Table 2: Multiple regression coefficients.

Coefficients Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -700788.7 205836.2 -3.405 0.003 **

Spending cols 11910.2 3512.3 3.391 0.003 **

Teaching staff primary -1128.1 427.1 -2.641 0.015 *

Teaching staff secondary 2378.5 208.6 11.404 0.000 ***

Teaching staff tertiary -980.3 529.1 -1.853 0.077 .

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1'’ 1

In assessing relationships between educational

resourcing and economic growth, these descriptive

statistics provide an overview of relevant input trends.

As hypothesized, government education spending

appears relatively stable or slightly increasing over

2010-2020. The research hypothesis that government

spending on education is positively associated with

GDP growth can be partially assessed by visualizing

or modeling the relationship between the spending and

GDP variables. These summary statistics offer a high-

level overview of the spending data before conducting

a more in-depth analysis.

The table also shows the mean spending and

teacher's summary. The mean education expenditure

as a percentage of GDP from 2010-2020 was 5.069%

across EU countries, with a variation between 3.227%

at the minimum and 7.519% at the maximum. This

aligns with the OECD (2021) EU22 average of 4.9%

over the period.

Regarding teaching staff inputs, the number of

primary teachers varies widely, from 12 to 1026.

Kirkness (2022) similarly highlights primary teacher

shortages in some EU systems. Secondary teachers

range from 18 to 2363, while tertiary staff range from

5 to 1037 (Kirkness 2023). As Murtin et al. (2018)

discuss, teacher numbers depend on demographics,

class sizes, and school organization policies.

Figure 1 show the bar chart of the same. Figure 1

shows the EU countries' 2020 GDP in ascending

order. From the figure, Malta had the lowest GDP,

while Germany had the highest GDP among the EU

countries.

Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the Impact of Educational Input on Economic Growth in the EU

145

3.2 Correlation Analysis

The correlation analysis examines the relationships

between educational inputs and economic growth in

EU countries. As hypothesized, government

expenditure on education appears positively

associated with GDP (r ranging from 0.60-0.86 from

2010-2019 with 2020 GDP). This aligns with past

research finding that increased spending on education

supports economic development by creating a more

skilled, productive workforce (Baldwin & Borrelli,

2008). However, the strength of the correlation has

declined in recent years. Danielle and Eric (2023)

cautions that simply increasing funding does not

guarantee improved outcomes, arguing the quality and

efficiency of spending matters more (Danielle and

Eric 2023). This raises questions on whether EU

countries are allocating education funds effectively

amidst recent budget constraints.

Unexpectedly, the number of teaching staff at all

levels correlates negatively with GDP, contradicting

the hypothesized positive link. The tertiary level sees

the strongest negative association (r=-0.20). This

contrasts with prior studies that found tertiary

education vital for growth in advanced economies by

spurring innovation (Grover 2010). The negative

correlation may reflect differences in teacher quality

and productivity between countries. For instance,

some research finds countries with higher teacher

salaries relative to GDP tend to perform better

academically (Carnoy 2009). Pay, working

conditions, and social status of teaching roles may

shape the ability of EU countries to recruit and retain

quality instructors. More nuanced analysis is needed

to unpack these relationships.

3.3 Regression Analysis

Table 2 is a multiple linear regression output table.

This multiple linear regression analysis provides

additional insights into the relationships between

educational inputs and economic growth based on the

data for EU countries.

Table 3 shows the multiple regression model

results. The model with government education

spending and primary, secondary, and tertiary

teaching staff numbers as predictors accounts for

95.8% of the variation in 2020 GDP. This high R-

squared value indicates these key educational factors

explain most of the differences in economic outcomes

between countries.

Table 3: Multiple regression model.

Model

Multiple R-Square 0.9577

Adjusted R-squared 0.95

F-statistic 124.4

p-value 9.05E-15

Residual standard error 200300

GDP = β

0

+ β

1

* Education Spending + β

2

*

Teaching Staff Primary + β

3

* Teaching Staff

Secondary + β

4

* Teaching Staff Tertiary + ϵ (1)

Looking at individual predictors, increased

government spending and larger secondary teaching

workforces are significantly associated with higher

GDP at p<0.01. A 1 unit increase in spending predicts

a $11,910 rise in GDP, supporting the importance of

education budgets for growth found in the correlation

analysis.

Meanwhile, more secondary teachers predict a

$2,378 GDP increase per staff member. This echoes

research finding secondary education as pivotal for

developing the broad-based skills needed in modern

economies (Hanushek and Woessmann 2023).

However, more primary teachers are linked to

lower GDP at p<0.05, and tertiary teachers show a

negative coefficient at p=0.077. This contrasts typical

views of early childhood and advanced education as

driving growth. The complexity of these relationships

merits further investigation through techniques like

multi-level modeling considering system-level

policies and outcomes.

3.4 Time Series

The time series plot and summary statistics provide

insights into how government education spending has

changed over time in the EU countries from 2010-

2020. As shown in figure 2, the time series shows

spending as a percentage of GDP declining between

2010-2013, followed by relative stability from 2014-

2020. The mean spending dropped from 5.63% in

2010 to 5.22% in 2013 before recovering slightly. This

aligns with research findings many EU countries cut

education budgets due to fiscal pressures following

the global financial crisis (European Commission

2013).

DAML 2023 - International Conference on Data Analysis and Machine Learning

146

Figure 2: Time series plot (Photo/Picture credit :Original).

However, the minimum spending remained above

3.4% of GDP even during periods of decline. This

highlights education as a continued policy priority

amidst constraints. The European Commission (2021)

stresses the need for sustained public investment in

human capital to increase economic resilience.

The relative stability of mean spending from 2014-

2020 suggests potential stabilization of budgets. Yet

the maximum percentage declined from 8.56% to

6.71% over the decade, indicating fewer countries

prioritizing very high investments in education.

Table 4: Model fitting.

Model

Results

ARIMA Model Specification

ARIMA (1,1,0)

Differencing Order

Autoregressive Terms 1 (AR1 coefficient = -0.665)

Moving Average Terms 0

AIC 42.12

Training Error (RMSE) 1.507

Training Error (MAE) 1.176

Training Error (MAPE) 21.6%

Residual Autocorrelation (ACF1) -0.264

As shown in table 4, The ARIMA model shows

that spending is relatively stable, with short-term

fluctuations. While these results suggest a

fundamental link between resources and growth,

ongoing analyses should incorporate additional

educational input, take into account country-specific

factors, and test for more complex relationships.

Overall, the time series and descriptive statistics

reveal interesting trends in government prioritization

of education spending in the EU. Initial cuts

potentially related to economic shocks were followed

by renewed consistency, though at moderately lower

levels on average. This provides context on policy

changes that may have impacted education quality

and economic outcomes over the past decade.

4 CONCLUSION

This research found noteworthy associations between

key education inputs and economic growth among

EU member states over the past decade. Government

spending on education demonstrates a moderately

positive correlation with GDP, confirming the

hypothesized link. Meanwhile, in regression analysis,

secondary teaching staff exhibit the strongest positive

predictive relationship with GDP growth. However,

surprising negative coefficients emerged for primary

and tertiary teachers. As table 4 shows ARIMA

modeling underscored the overall stability of

spending but with short-term fluctuations.

Several implications arise for education policy

and planning in the EU context. Firstly, continued

public investment in the sector appears important for

human capital development, but quality and equity

considerations must complement budgets. Tailoring

spending to evidence-based initiatives with growth

returns is advised over across-the-board increases.

Supporting secondary education emerges as

impactful currently, but a balanced and adaptable

overall system remains vital.

Moreover, increased regional coordination on

priorities like teacher training, mobility initiatives,

and learning standards could optimize quality. More

granular analysis of country-level inputs, outputs, and

needs is warranted. Further research should

incorporate additional metrics like test scores,

graduation rates, and social equity data.

Overall, this multivariate analysis demonstrates

positive associations between key educational

resourcing factors and economic outputs in the EU

region. While the relationships are complex, strategic

investments informed by statistical modeling

evidence can strengthen productivity and resilience.

The quantitative techniques illustrate the depth of

insights possible from thoughtful data analysis.

Ongoing research should compile expanded panel

datasets and utilize modeling approaches tailored to

these complex dynamics. As the EU strives to build

human capital and foster shared prosperity, evidence-

based policymaking will be key to providing high-

quality, equitable education opportunities to all

citizens.

Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the Impact of Educational Input on Economic Growth in the EU

147

REFERENCES

Toader, Firtescu, Roman, and Anton - Impact of

Information and Communication Technology

Infrastructure on Economic Growth: An Empirical

Assessment for the EU Countries - Sustainability, vol.

10, no. 10, pp.3750, 2018.

OECD - Productivity, human capital, and educational

policies - OECD. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.

org/economy/human-capital/, 2022.

Pietro, Biagi, Costa, KarpińskiZ. and Mazza - The likely

impact of COVID-19 on education: reflections based on

the existing literature and recent international datasets -

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European

Union, 2020.

Eurydice (European Education and Culture Executive

Agency) - The European higher education area in 2020:

Bologna process implementation report - Publications

Office of the European Union. LU: Publications Office

of the European Union. Retrieved from:

https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/756192, 2020.

European Commission's Directorate - General for

Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. Education and

Training Monitor 2022: Comparative report.Retrieved

on September 10, 2023

Åse Gornitzka. Organizing Soft Governance in Hard Times

- The Unlikely Survival of the Open Method of

Coordination in EU Education Policy. European Papers

- A Journal on Law and Integration, no.10, pp.235–255,

2018.

Creswell, and Creswell - Research design: Qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches - Sage

publications, 2017.

Chatfield, and Xing - The Analysis of Time Series: An

Introduction with R - Milton: CRC Press LLC, 2019.

Eric and Ludger - The Knowledge Capital of Nations:

Education and the Economics of Growth - Cambridge;

London: The Mit Press, Cop, 2023.

European Commission - Digital Education Action Plan

(2021-2027) European Education Area -

Education.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved from:

https://education.ec.europa.eu/focus-topics/digital-

education/action-plan, 2021.

OECD - Review Education Policies - Education GPS -

OECD. Oecd.org.Retrieved from:

https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/

#, 2022a

Seeram - An Overview of Correlational Research -

Radiologic Technology, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 176-179,

2019.

Gujarati - Basic Econometrics. Prentice Hall, 2022.

Kirkness - Shifting Tides: New Zealand's Foreign Policy

Shift in the Pacific a Small State's Response to

Changing Global Challenges - ProQuest.

www.proquest.com. Retrieved on September 14, 2023.

OECD - Review education policies - Education GPS

OECD. Oecd.org. Retrieved from:

https://gpseducation.oecd.org/revieweducationpolicies/

#, 2022b

Danielle and Eric - Nber Working Paper Series U.S. School

Finance: Resources And Outcomes - National Bureau

Of Economic Research. Retrieved from:

http://www.nber.org/papers/w30769, 2023.

Grover - “Russ” W. Spurring Innovation Through

Education: Four Ideas. Retrieved from:

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/spurring-

innovation-through-education-four-ideas, 2010.

Carnoy, Brodziak, Luschei, Beteille, and Loyalka -

Teacher Education and Development Study in

Mathematics (TEDS-M): Do Countries Paying

Teachers Higher Relative Salaries Have Higher Student

Mathematics Achievement? - International Association

for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

Herengracht 487, Amsterdam, 1017 BT, The

Netherlands, 2009.

Hanushek and Woessmann - The Knowledge Capital of

Nations: Education and the economics of growth - MIT

Press, 2023.

European Commission - Directorate-General for

Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, Education and

training monitor. Publications Office, 2013.

DAML 2023 - International Conference on Data Analysis and Machine Learning

148