UK Students’ Concerns About Security and Privacy of Online Higher

Education Digital Technologies in the Coronavirus Pandemic

Basmah Almekhled

1,2 a

and Helen Petrie

1b

1

Department of Computer Science, University of York, Heslington East, York, U.K.

2

College of Computing and Informatics, Saudi Electronic University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Keywords: Online Higher Education, Privacy and Security Concerns, Videoconferencing Technologies, Online Chat

Technologies, COVID Pandemic.

Abstract: The coronavirus pandemic has led to major changes in higher education around the world. Higher education

institutions (HEIs) moved to completely online learning and a range of new technologies including online

videoconferencing and chat tools. Research has shown that users have privacy and security concerns about

such tools, but little is known about the attitudes of HEI students to these issues, apart from reluctance to use

webcams during online teaching. A survey of 71 UK HEI students explored attitudes and concerns about

privacy and security in online teaching in the pandemic. Participants knew little about institutional policies

on these issues and few had had any training. Ratings of concern across a range of issues were generally low,

however in open-ended questions, a range of concerns such as being recorded without permission,

unauthorised people entering and disrupting of online sessions, not knowing where recordings are stored and

who has access to them. The main concerns about online teaching situations related to being monitored in

examinations. HEIs moved very rapidly to deploy online technologies for teaching in response to the

pandemic, but going forward, more transparency and information to students could alleviate many of these

concerns and create better informed students.

1 INTRODUCTION

As a result of the coronavirus pandemic, higher

educational institutions (HEIs) around the world were

suddenly forced to move largely to online teaching.

UNESCO (2021) estimates that more than 220

million students in higher education were affected by

the pandemic. Students began to learn and study

online at very short notice and without the

expectation that this would be the way they would

have undertaken their courses and assessments. This

transition required major changes in teaching and

learning methods. Face-to-face lectures, seminars,

practicals and other teaching methods were replaced

with online equivalents were possible or suspended if

this was not possible. Examinations were online or

changed to different online assessments. This

precipitous change caused considerable stress for

both teachers (Watermeyer et al., 2021) and students.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9985-7869

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0100-9846

Although many HEIs were already using online

systems such as virtual learning environments

(VLEs) before the pandemic, the use of a range of

different technologies greatly increased when HEIs

moved to fully or nearly fully online teaching. Our

own institution is probably typical in that within days

of the first lockdown in the United Kingdom, the

institution purchased an enterprise level version of

Zoom, set up Slack and Discord channels for students

and staff at every level, and initiated discussion of

how we would conduct the end of year examinations

remotely via these technologies. This sudden move to

the use of many different digital technologies also

initiated much discussion of the privacy and security

issues related to their use: how would we monitor

whether students were participating in sessions, was

it necessary for staff and students to have their

microphones and webcams on during sessions, how

would assessments and examinations be monitored

for collusion and cheating and so on? The rapid

Almekhled, B. and Petrie, H.

UK Students’ Concerns About Security and Privacy of Online Higher Education Digital Technologies in the Coronavirus Pandemic.

DOI: 10.5220/0011993500003470

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2023) - Volume 2, pages 483-492

ISBN: 978-989-758-641-5; ISSN: 2184-5026

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

483

actions and discussions at our institution were clearly

not unique, several studies of HEI educators’

experiences of the pandemic (Müller et al., 2021;

Watermeyer et al., 2021) highlight very similar

issues.

Although not specifically about educational use of

digital technologies, a worldwide survey conducted in

May 2020, several months into widespread remote

working and teaching due to the pandemic, found that

privacy and security factors were the most frequently

mentioned in relation to the use of conferencing and

communication tools (Emami-Naeini et al., 2021).

Another large general survey taken a few months

before the pandemic also found that users were

concerned about the security and privacy of group

chat technologies (Oesch et al., 2020). These are the

kinds of digital technologies that many HEIs began

employing for online teaching druing the pandemic,

often with rapid and ad hoc deployment.

A number of studies investigated HEI students’

attitudes and concerns in relation to online privacy

and security before the pandemic, but these are

generally about their general attitudes and concerns,

and not in relation specifically to their online

education. For example, Kim (2013) surveyed 85

American university students and found they had a

good understanding of online security issues. One

question related to their educational experience, only

40% of respondents thought that their personal

information was adequately protected in the

institution’s online systems. Khalid et al. (2018)

surveyed 142 Malaysian HEI students and found they

had typical concerns about online privacy and

security (e.g. that their personal information might be

shared without their permission) but also good

knowledge of protective actions (e.g. to ignore

requests for information from strangers). However,

these questions were posed in relation to general

online privacy and security, not specifically about the

educational context.

In addition, a number of studies have investigated

HEI students’ experiences of digital technologies

during the pandemic, in a wide range of countries and

situations, although only one study could be found

which focused specifically on privacy and security

issues of the technologies being used. Kim (2021)

investigated the attitudes of 296 South Korean HEI

students using a technology acceptance model (TAM)

(Davis et al., 1989) framework and found that

concerns about online privacy and security negatively

impacted on students’ intention to participate in live

online teaching sessions.

More general studies of students’ attitudes to

online teaching included Serhan (2020) who found

that a sample of US university students were positive

about using Zoom for online teaching, although

concerns about privacy were raised tangentially. A

study in India (Agarwal & Kaushik, 2020) also found

that university students were positive about Zoom

sessions, although a study from Pakistan (Adnan &

Anwar, 2020) found that the majority of students felt

that face-to-face teaching was vital for learning.

Two studies were identified which investigated

HEI students’ attitudes to the use of webcams in

online teaching and specifically why students do not

want to have them on during online teaching sessions

(Bedenlier et al., 2021; Gherhes et al., 2021).

Although conducted in different countries (Germany

and Romania), both found reluctance on the part of

students to have webcams on during online teaching

sessions. A range of reasons were proposed,

including shyness and anxiety, but both studies

highlighted privacy issues as major concerns. Yet,

the educators in the study by Müller et al (2021)

highlight the difficulty of engaging with students who

cannot be seen in online teaching sessions.

Given the paucity of information about HEI

students’ concerns about the privacy and security

issues of the numerous technologies now being

deployed in online teaching, technologies which are

very likely to continue to be used to some extent even

as face-to-face education has returned, we set out to

investigate these concerns with a sample of HEI

students who had started their higher education before

the pandemic, but were now continuing their studies

during the pandemic (data were collected in

December 2021) . We chose to concentrate in the first

instance on a sample of students from the UK (those

studying in the UK and who are British), as

educational practices at HE level can vary between

countries. In addition, students from different

cultures may well have different attitudes to online

privacy and security in general and specifically in

relation to their education. Some research has found

substantial cultural differences in these areas (Cho et

al., 2009; Trepte et al., 2017), although this is not

always the case (Petrie & Merdenyan, 2016). Thus,

investigating a culturally and educationally

homogenous sample should allow us to draw clearer

conclusions.

Our research questions were, in the context of the

pandemic:

RQ1: What do HEI UK students understand by online

privacy and security?

RQ2: Are UK HEI students aware of their

institution’s policies about online privacy and

security issues and are they provided with training

about these issues?

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

484

RQ3: What are UK HEI students' concerns about

privacy and security issues in relation to using video

conferencing and online chat technologies for online

teaching and studying?

RQ4: What are UK HEI students’ concerns about

privacy and security issues in relation to a range of

specific online teaching and learning situations?

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited via the Prolific

recruitment site (prolific.co). The inclusion criteria,

were to be British, studying at a UK HEI and to have

been studying there since before the coronavirus

pandemic started (i.e. to have started studying in the

2019 – 2020 academic year or earlier). Data were

collected in December 2021 and this paper addresses

students’ current situation, that is study in the

pandemic situation of enforced distance learning.

75 students responded, but data from four were

discarded because they had not started studying

before the pandemic, leaving a sample of 71

participants. Demographic information for the sample

is shown in Table 1. All those who responded

received a payment of GBP 2.00 for completing the

survey.

The age range was surprisingly wide (18 - 67

years), but 50 participants (70.4%) were 25 years or

younger, and 60 (84.5%) were 30 or younger. The

sample was somewhat biased toward women (63.4%

women), probably due to the tendency of women to

volunteer for research [19].

Participants were studying at 46 different UK

HEIs, representing every type of HEI from the elite

universities (Oxford and Cambridge) to the newer

HEIs. No one HEI had more than three participants.

Most participants were studying at HEIs in England

(61, 85.9%), but with some representation from

Scotland (6, 8.5%), Wales (3, 4.2%) and Northern

Ireland (1, 1.4%).

The distribution of degree levels is quite close to

the overall UK higher education population, statistics

from the Higher Education Statistics Agency [10]

show that 73.0% of students are enrolled in Bachelor

level degrees, 22.9% at Masters level and 4.1% at

PhD or other research degrees. The distribution of

major subjects of study is not so close to the overall

UK higher education population [11] with over-

representation of participants studying arts and

humanities, computer science, engineering and

mathematics, physical and social sciences, and under-

representation of students studying business studies.

However, the sample did include participants

studying a wide range of subjects in both the sciences

and humanities.

Table 1: Demographics of the participants.

Age

Range

Mean

Standard deviation

18 – 67

25.6

8.9

Gender

Men

Women

Non-

b

inar

y

25 (35.2%)

45 (63.4%)

1 (1.4%)

Degree level

Bachelor

Masters

PhD

56 (78.9%)

10 (14.1%)

5

(

7.0%

)

Academic year started

2019 - 2020

2018 - 2019

2017 - 2018

Earlie

r

47 (66.2%)

19 (26.8%)

1 (1.4%)

3 (5.6%)

2.2 Online Questionnaire

A questionnaire was designed to explore attitudes and

concerns about privacy and security issues in relation

to online teaching and learning. The questionnaire

asked about attitudes and concerns held before the

pandemic and since the pandemic, however this paper

will concentrate on issues since the pandemic. The

questionnaire included four sections relevant to this

paper.

Before providing a definition of “online privacy

and security” for the survey, participants were asked

what this phrase meant to them. A working definition

for the survey was then provided: “that a person’s

data, including their identity, is not accessible to

anyone other than themselves and others who they

have authorised and that their computing devices

work properly and are free from unauthorised

interference” (based on our reading of a range of

sources, (e.g. NCSC, 2022; Schatz, 2017; Steinberg,

2019; Windley, 2005). This was to ensure that

participants did understand what we were asking

about in subsequent sections.

The four main sections of the questionnaire used

a mixture of Likert rating items and open-ended

questions. The sections were:

About the Participant’s Institution: asked where

the participant is studying, major subject of study,

qualification they are studying for, and when they

started studying in HE. Also, asked whether their

institution has policies in relation to online privacy

UK Students’ Concerns About Security and Privacy of Online Higher Education Digital Technologies in the Coronavirus Pandemic

485

and security and provides training to students on these

issues.

Privacy and Security Concerns About

Videoconferencing and Chat Technologies in

Teaching and Learning: asked about participants’

experiences and concerns of online security and

privacy specifically about videoconferencing and

chat technologies in their teaching and learning.

Questions also addressed concerns about security and

privacy issues in relation to the different activities

such as using videoconferencing and online chat

technologies in teaching sessions or with other

students.

Privacy and Security Concerns About a Range of

Particular Online Teaching, Learning and

Studying Situations: asked about concerns about

security and privacy issues relevant to online teaching

(e.g. online sessions being recorded without the

participant’s knowledge, unauthorised people

attending online teaching sessions). Questions also

addressed attitudes and practices around the use of

webcams during teaching and study activities. This

set of situations was developed from our reading of

the literature and by brainstorming with a number of

HEI educators about their experiences since the

pandemic. We opted to ask about a range of specific

situations, as a completely open-ended question on

this topic might not elicit much specific information.

Demographics: asked basic questions about age,

gender, and how knowledgeable participants rated

themselves about online privacy and security issues

and videoconference and chat technologies.

The online questionnaire was deployed using the

Qualtrics survey software in December 2021. A pilot

study with five students at our own institution was

conducted to assess the clarity of the questions and

the time required to complete the survey. Some small

adjustments were made. The survey received ethical

approval from the University of York Physical

Sciences Ethics Committee.

2.3 Data Preparation

The questionnaire elicited both quantitative (answers

to multiple choice questions and 7-point Likert items)

and qualitative data (answers to open-ended

questions). The Likert items were often very skewed

to the lower part of the scale, so analysed using non-

parametric statistics. Medians and semi-interquartile

ranges (SIQRs) were calculated instead of means and

standard deviations and the Wilcoxon One Sample

Signed Ranks Test was used to test whether the

distribution of ratings differed from the midpoint of

the scale. As the sample size is large (more than 30

observations), the Z statistic for the normal

distribution approximation was used instead of the

Wilcoxon T (Siegel & Castellan, 1988).

Thematic analysis was conducted separately on

each open-ended question. Inductive thematic

analysis was used (Braun & Clarke, 2006), as no a

priori assumptions were made about the themes

which would emerge. The typical thematic analysis

procedure was used of reading through all the

answers to a particular question several times,

developing a preliminary set of themes, and then

working through the material repeatedly to refine

those themes and where appropriate, create sub-

themes. In some cases, themes were sub-divided into

sub-themes (see Tables 2 and 3), but as these were

relatively small thematic analyses (71 responses in

Table 2, 28 in Table 4, 22 in Table 6), this was not

always the case.

3 RESULTS

Before addressing the four research questions, we

briefly present results on participants’ experience of

online teaching and studying and how that changed

due to the pandemic.

Participants were asked whether their teaching

before the pandemic was totally online, totally face-

to-face, or blended (i.e. a mixture of face-to-face and

online). 60 participants (84.5%) reported that it had

been totally face-to-face, with only 5 (7.0%) reporting

totally online teaching, and 6 (8.5%) blended

teaching. In response to the pandemic, teaching for

the majority of participants (54, 76.1%) moved (or

remained) totally online (participants whose teaching

did not move totally online were mainly in medicine,

physics, chemistry or biology). Thus, for a majority

of participants (44, 62.0%) the pandemic resulted in a

radical of teaching methods, from totally face-to-face

to totally online.

3.1 RQ1: Students’ Understanding of

Online Privacy and Security (RQ1)

Initially, participants were asked to provide their

understanding of online privacy and security in their

own words. This was a compulsory question, so all 71

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

486

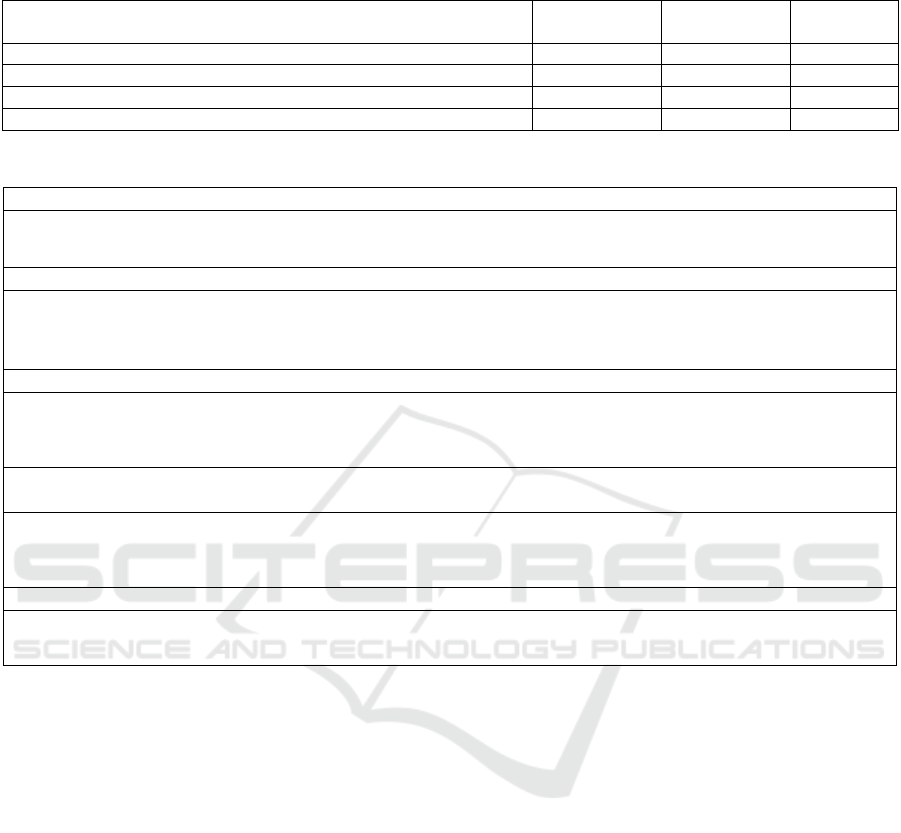

Table 2: Participants’ understanding of online security and privacy (based on answers from all 71 participants).

MAIN CATEGORY/sub category Examples

SECURE (Mentioned by 30 participants, 42.3%; 32 distinct mentions, 23.0%)

Data/information

18

(

56.3%

)

keeping my data, work and login details secure (P4)

Kee

p

in

g

m

y

information secure … whilst stud

y

in

g

online

(

P46

)

During online activities

10

(

31.3%

)

… being safe .. while using the Internet (P13)

Attendin

g

over a secure

p

latform i.e. Microsoft teams

(

P69

)

In accessing institution resources

4 (12.5%)

being able to access institution resources safely (P11)

Making sure my university site is secure (P36)

PRIVATE (Mentioned by 20 participants, 28.2%; 21 distinct mentions, 15.1%)

Data/information

14 (66.7%)

Keeping your information …. private within the university (P43)

Keeping all personal data and the course

p

rogress of students private (P49)

During online activities

7 (33.3%)

Being able to participate in online lectures without other students and

lecturers being able to see and hear people in the background of your home

(P11)

Having a private connection when attending online classes and meetings

(P69)

PROTECTION

(

mentioned b

y

17

p

artici

p

ants, 23.9%, 15 mentions, 10.8%

)

having reliable … protection against online threats (P21)

… protection of personal data (P27)

NOT ACCESSIBLE (mentioned by 16 participants, 22.5%; 17 distinct mentions, 12.2%)

Unauthorised persons are not able to access

data

… making sure that personal information, passwords, private files cannot

be accessed without my permission … (P25)

my details are only available on an as requested basis and only to the

university (P47)

STOLEN, HACKED, LEAKED, SHARED (mentioned by 13 participants, 18.3%; 16 distinct mentions,11.5%)

Data cannot be stolen, hacked, leaked won’t risk my passwords or data being leaked (P24)

… my information online is … not vulnerable to be stolen (P44)

NOT SHARED (mentioned by 8 participants, 11.3%; 8 distinct mentions, 5.8%)

Data cannot be shared (without permission) That your data cannot be … passed on (P20)

Your data is not shared outwith relevant

g

rou

p

s

(

P41

)

PREVENT USE WITHOUT PERMISSION OR MISUSE (mentioned by 8 participants, 11.3%, 7 mentions, 5.0%)

…someone else using my information without my permission for their

benefit (P10)

my information online is … not vulnerable to be used in a harmful way

(

P44

)

participants provided an answer. Results of the

thematic analysis of responses are summarised in

Table 2. Nearly half the participants (30, 42.3%)

produced somewhat circular definitions by using the

term “secure” (or close variations) and more than a

quarter (20, 28.2%) used “private” (or close

variations). However, many participants elaborated

with what was secure or private, most commonly their

data, but also their online activities and their access to

their institution’s resources. Smaller numbers of

participants brought in different concepts such as

their data being protected (17, 23.9%) or not

accessible (except to those authorised, 16, 22.5%) or

not able to be stolen, hacked or leaked (13, 18.3%),

shared without permission (8, 11.3%) or not mis-used

(8, 11.3%). Smaller numbers of participants (less than

10%) also mentioned preventing scams, anonymity in

online activities, having control over one’s data and

confidentiality.

3.2 Students’ Awareness of

Institutional Policies About Online

Privacy and Security Issues and

Training (RQ2)

Participants were asked if they knew whether their

institution has policies about privacy and security

issues in relation to the use of technologies for online

teaching and learning (e.g. videoconference systems,

online chat systems). Less than one third of

participants (21, 29.6%) knew of such policies, a

small number (5, 7.0%) said they thought the

institution did not have any policies, and the majority

UK Students’ Concerns About Security and Privacy of Online Higher Education Digital Technologies in the Coronavirus Pandemic

487

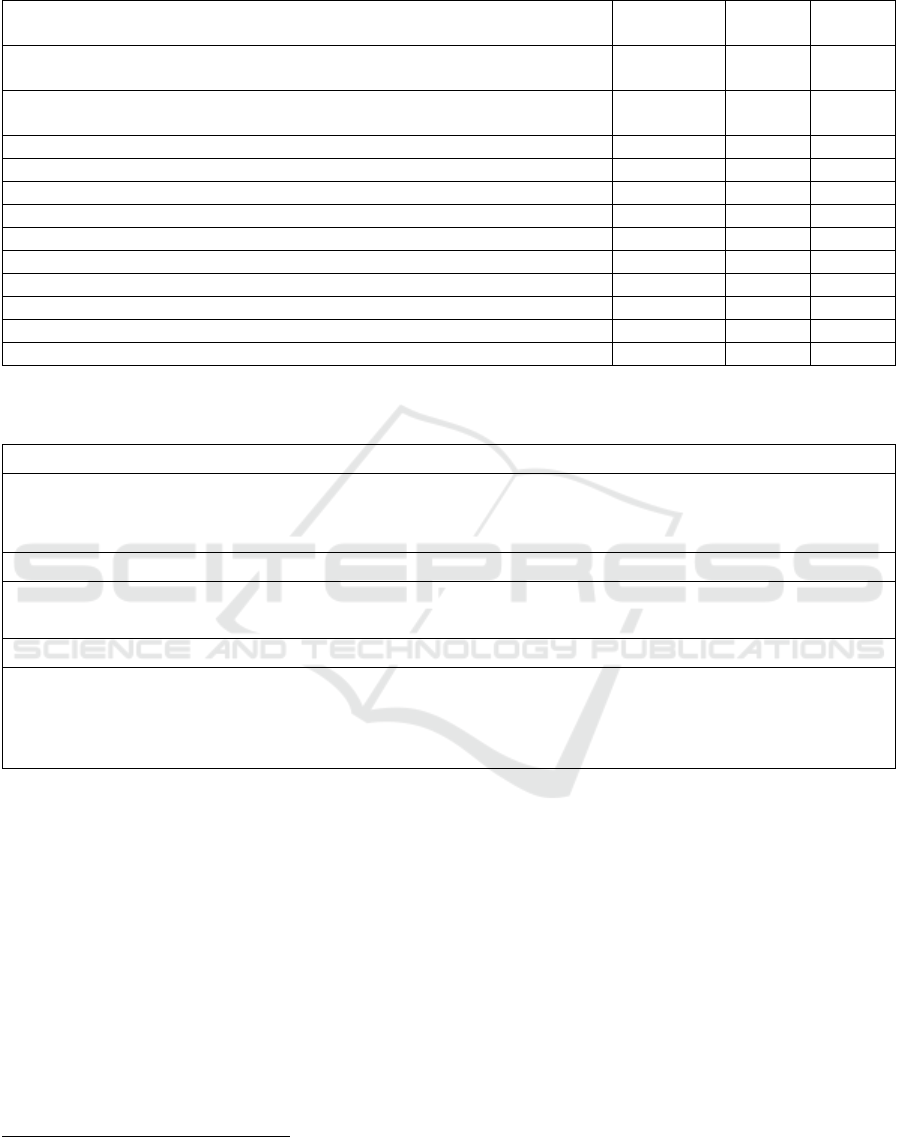

Table 3: Participants’ level of concern about online security and privacy about using video conferencing and chat technologies

in online teaching and studying (rated from 1 = not at all concerned to 7 = very concerned).

Issue

Median

(SIQR)

Z p

Usin

g

video conferencin

g

technolo

g

ies in teachin

g

sessions 1.00

(

0.50

)

-6.89 < .001

Usin

g

online chat technolo

g

ies in teachin

g

sessions 1.00

(

0.50

)

-6.53 < .001

Using video conferencing technologies in studying with other students 1.00 (1.00) -6.75 < .001

Using online chat technologies in studying with other students 1.00 (1.00) -6.70 < .001

Table 4: Participants’ concerns about videoconferencing and online chat technologies (based on 28 participants).

BEING RECORDED (WITHOUT PERMISSION)

(

mentioned b

y

6

p

artici

p

ants, 21.4%

)

It's also easy to record things without anyone's permission or knowledge (P32)

People being recorded when they don’t consent to be (P38)

UNAUTHORISED PEOPLE BEING IN A SESSION (AND DISRUPTING IT)

(

mentioned b

y

6

p

artici

p

ants, 21.4%

)

There have been cases of random people joining Zoom calls if they are public and then causing chaos until they get kicked

out (P13)

There's always a risk of someone joining without invitation (P43)

LACK OF TRUST IN THE INSTITUTION OR THE TECHNOLOGY

(

mentioned b

y

6

p

artici

p

ants, 21.4%

)

I just don't trust the university websites as they are very outdated (P29)

I'm more concerned about online chat technologies as these are run by companies like Facebook which I don't trust (vs

trust Zoom etc slightly more) (P66)

NOT KNOWING WHO CAN ACCESS RECORDINGS OF SESSIONS OR WHERE THEY ARE STORED

(mentioned by 5 participants, 17.9%)

The recorded sessions go online with our information and video and its hard to know who can access it (P16)

I would want to know .. who will have access to it [the recording], especially if I personally have participated in the

conversation or had my camera on .. I would want to know where [the recording] will be stored (P19)

CAMERA/MICROPHONE ON/OFF?

(

mentioned b

y

4

p

artici

p

ants, 14.3%

)

… that I will accidentally turn my camera on when I don't mean to (P63)

Worries of camera / mic being on when you are not aware that they are (P64)

of participants (45, 63.4%) said they were not sure or

did not know.

When asked whether their institution provides

training in online privacy and security issues, a small

number of participants (10, 14.1%) reported that

training was provided, more reported that it was not

provided (16, 22.5%) and again, the majority were not

sure or did not know (45, 63.4%). Only two

participants (2.8%) reported having received any such

training.

3.3 Students' Concerns About Privacy

and Security Issues in Relation to

Video Conferencing and Online

Chat Technologies for Online

Teaching and Studying (RQ3)

Participants were asked to rate their level of concern

about security and privacy issues in relation to the use

of videoconferencing and online chat technologies for

teaching sessions and for studying with other students

(on 7-point Likert items, coded as 1 = not at all

concerned to 7 = very concerned, only the end point

wording was presented to participants). Table 3

shows that in all cases, they rated their concern as

very low (median of 1.0 or “not at all concerned” on

all four combinations, significantly below the

midpoint of the rating scale) with very small variance

(as measured by the SIQRs).

However, in a follow-up open ended question

about any concerns, 28 (39.4%) of participants did

raise concerns, including two who said they were not

concerned, but then raised concerns. The thematic

analysis of these concerns is summarised in Table 4.

Two of the most commonly mentioned concerns were

videoconferencing sessions being recorded without

permission, and who could access them (particularly

whether institution staff could access them) and

where they would be stored (although it was not

explicitly mentioned, this presumably related to the

security of the storage). The other most commonly

mentioned concerns were about unauthorised people

entering and disrupting online sessions (although no

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

488

participant reported this actually happening to them)

and a general lack of trust in either the institution, the

technology or the companies providing the

technology.

Participants were also concerned about knowing

whether their camera or microphone being on when

they are not aware of it and that others (again,

particularly staff) might be able to access their camera

or turn their camera or microphone off without their

knowledge or permission. Less frequently mentioned

concerns (mentioned by less than 10% of participants

who answered) included being involved in

discussions with other students who might do/say

something that would get the whole group into

trouble (this was one of the few concerns about other

students) and a number of concerns which were not

necessarily about online privacy and security, for

example not wanting to post a photo of oneself (this

could be a privacy concern, it was not clear), feeling

uncomfortable in online sessions, and it being “just

difficult to get points across, feels less authentic”

(P58) (all mentioned only by one participant).

3.4 Students’ Concerns About Privacy

and Security Issues in Relation to a

Range of Specific Online Teaching

and Learning Situations (RQ4)

Participants were asked to rate their level of concern

about online privacy and security issues in relation to

a range of specific online teaching and learning

situations (see Table 5). Two situations, both relating

to being monitored in online exams, had median

ratings of 4.0, which were not significantly different

from the midpoint of scale, which indicates a

moderate level of concern. All the other situations had

medians of 1.0 or 2.0 and were significantly below

the midpoint of the scale, meaning participants were

not particularly concerned about them. However, it

is interesting that a number of the situations were ones

which were commonly raised by participants in the

open-ended question about privacy and security

concerns in relation to video conferencing and online

chat technologies, namely online sessions being

recorded without their knowledge, unauthorised

people attending or disrupting online teaching

sessions.

Again, in a follow-up open-ended question

participants described their concerns. 22

participants(30.1%) raised concerns (see Table 6),

and three participants also raised positive aspects of

the online situation in relation to these issues. The

positive comments were the fact that online lectures

could be watched again to understand them better;

and that the chat facility in online sessions was very

useful for sharing comments and links; that online

sessions were password protected, which made the

participant feel secure.

In terms of the concerns, there was some overlap

with the answers to the previous open-ended question

(see Table 3), with the two most frequently mentioned

concerns (being recorded without permission and

unauthorised people being in an online session and

potentially disrupting it) also being the most

frequently mentioned in responses to the earlier

question. The additional concern most frequently

mentioned in response to this question was other

students making inappropriate comments in online

sessions (mentioned by 3 participants, 13.6%). Less

frequently mentioned concerns (mentioned by less

than 10% of the participants who answered) were

possibilities for plagiarism (mentioned by two

participants), one’s work being shared without

permission, that the teacher could turn the student’s

webcam or microphone on without alerting them, and

the issue of not wanting to post one’s photo

(discussed above in relation to RG3) (mentioned by

one participant each).

4 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated the attitudes and concerns

about privacy and security in online teaching and

learning of UK HEI students during the coronavirus

pandemic. In relation to RQ1, participants seemed to

have only a rather basic and perhaps overly simple

understanding of online privacy and security, but this

may be because they were asked in an online survey

and only felt the need to give a simple answer. It

would be important to follow up HEI students

understanding of these concepts and their mental

models of how online privacy and security work in

online education with more in-depth methods such as

interviews and focus groups.

In relation to RQ2, less than one third of

participants knew whether their HEI had any policies

about online privacy and security and only two

(2.5%) had received any training in this area. A

separate question is whether HEIs have clear policies

in these areas. What precautions are taken to ensure

that only eligible students attend online sessions, are

students (and staff) required to have webcams on

during online sessions, what is recorded in sessions

(just the video or also the chat discussion), how

private and secure are informal channels such as

UK Students’ Concerns About Security and Privacy of Online Higher Education Digital Technologies in the Coronavirus Pandemic

489

Table 5: Participants’ level of concern about online security and privacy about particular teaching and learning situations

(rated from 1 = not at all concerned to 7 = very concerned).

Issue

Median

(SIQR)

Z p

Having to turn on your webcam during an online exam to allow the teacher to

monitor

y

ou in real-time

4.00 (2.00) 0.03 n.s.

Having to video record yourself during online exams so a teacher can review the

video late

r

4.00 (2.00) 0.29 n.s.

Other students making recording or screenshots without permission 2.00 (1.50) -4.68 < .001

Your work bein

g

used as exam

p

les without

y

our

p

ermission 2.00

(

1.50

)

-5.36 < .001

Other students makin

g

recordin

g

or screenshots without

p

ermission 2.00

(

1.50

)

-4.68 < .001

Other students making inappropriate comments (sexist, racist) 2.00 (1.50) -5.66 < .001

Online lectures/seminars bein

g

recorded without

y

our knowled

g

e 1.00

(

1.00

)

-6.33 < .001

Unauthorised

p

eo

p

le attendin

g

online teachin

g

sessions 1.00

(

1.00

)

-5.89 < .001

Unauthorised people interrupting online teaching session 1.00 (1.00) -6.09 < .001

Other students harassin

g

y

ou 1.00

(

0.50

)

-7.04 < .001

Your teacher not turnin

g

on their webcam in teachin

g

sessions 1.00

(

0.50

)

-6.87 < .001

Other students not turning on their webcams in online sessions 1.00 (0.50) -7.05 < .001

Table 6: Participants’ concerns about online security and privacy in particular teaching and learning situations (based on

answers from 22 participants).

BEING RECORDED (WITHOUT PERMISSION) (mentioned by 6 participants, 27.3%)

Being recorded without my knowledge (P7)

Other students making recordings/screenshots: not that concerned as only likely personal data would be name/face (which

could also be found on social media etc.) (P66)

UNAUTHORISED PEOPLE BEING IN A SESSION (AND DISRUPTING IT) (mentioned by 5 participants, 22.7%)

Again, my main concern is around people hacking sessions (P3)

Interruptions in teaching sessions is probably the most concerning since it's the most likely thing to happen (P51)

INAPPROPRIATE COMMENTS FROM STUDENTS (mentioned by 3 participants, 13.6%)

There was one issue where a student made some inappropriate comments in the chat feature during a live session, this was

dealt with well by the professor … (P58)

Inappropriate comments/harassment: slightly concerned but this is no different to when this could happen before pandemic

(P66)

Slack or Discord? There are many issues where

privacy and security policies are needed. A starting

point may be the General Data Protection Regulation

(GDPR), but much more specific policy is required in

these areas. Granted, HEIs needed to move very

rapidly to deploy online technologies for teaching in

response to the pandemic, but our survey took place

in December 2021, when HEIs in the UK were still

largely teaching in a hybrid format, often with online

lectures but face-to-face seminars and practicals

1

, but

had had ample time to publicise policies and provide

students with appropriate training and support. This

would help students not only in their education, but

more generally in their online lives.

1

An informal survey of 18 UK HEIs found that 83% (15)

were teaching in such a hybrid format, with 17% (3)

teaching largely face-to-face.

On RQ3 and RQ4 the ratings of concern were very

low, apart from those relating to the monitoring of

examinations, suggesting that students were not

concerned about the many potential privacy and

security issues that many of their teachers had

undoubtedly stressed over. However, it was

interesting that in the responses to the follow-up

open-ended questions a substantial minority of

participants then raised numerous concerns. We need

to conduct further analysis to investigate whether

these participants did in fact give higher concern

ratings. However, this shows the importance of not

relying on quantitative data alone, which in this

instance may have been susceptible to socially

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

490

desirable answers (students not wanting to appear

overly concerned). However, this apparent lack of

concern on the part of UK HEI students is somewhat

at odds with studies which have shown concerns

amongst the working population about online privacy

and security issues (Emami-Naeini et al., 2021; Oesch

et al., 2020). Do students trust their institutions more

than workers or are they simply less worried about

these issues in an educational context? The results

also differ from those from Kim (2013), admitted data

from well before the pandemic and in a country

without GDPR, which found that a sample of

American HEI students tended not to think their

personal information was adequately protected by

their institution.

Although we did not specifically ask participants

whether they had personally experienced any of the

privacy and security issues asked about in the

questionnaire, ongoing analysis of the open-ended

questions suggests that very few participants had

actual experience of the issues they were concerned

about but had heard or thought about these issues.

There were numerous uses of hypothetical phrases

such as “people taking photos could be a concern….”

(P63) and “I would be uneasy if …” (P55). There was

only a very few instances in which a participant

recounted an experience in some detail which they

had clearly experienced personally. Thus, some of

the concerns, such as online sessions being

“Zoombombed” or teachers being allowed to turn on

students’ webcams or mikes without their permission

could be alleviated with greater transparency and

information to students from their HEIs.

A particular limitation of this study is that

although a sample of 71 students from a range of UK

HEIs is very adequate for the quantitative analysis

and amount of data for the qualitative analysis was

relatively small. It was necessary to make most of the

open-ended questions optional – participants could

not answer about concerns they did not have, but we

also did not want to make the questionnaire too

onerous to complete. Thus, some participants who

did have concerns might not have written about them,

but more importantly the sample of students with

concerns was not large (28 for RQ3 and 22 for RQ4).

Thus, more data and different methods are needed to

explore these issues further, but this study provides

some initial pointers of interest.

As mentioned in the Introduction, we specifically

sampled the population of British students studying at

UK HEIs. The attitudes and concerns of international

students studying in the UK may be different, and the

attitudes and concerns of students studying at HEIs in

other countries is very likely to be very different.

That is a topic we will address in further research. In

addition, the questionnaire also asked about students’

attitudes and concerns before the coronavirus

pandemic and how the pandemic had changed their

attitudes. This will be the focus of further analysis of

our data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the students who

participated in the survey for their time and effort in

answering quite a long set of questions.

REFERENCES

Adnan, M. & Anwar, K. (2020). Online learning amid the

COVID-19 pandemic: students’ perspectives. Journal

of Pedagogical Sociology and Psychology, 2(1), 45 –

51.

Agarwal, S. & Kaushik, J.S. (2020). Students’ perception

of online learning during COVID pandemic. Indian

Journal of Pediatrics, 87(7), 554. https://doi.org/10.

1007/s12098-020-03327-7

Almaiah, M.A., Al-Khasawneh, A., & Althunibat, A.

(2020). Exploring the critical challenges and factors

influencing the e-learning system usage during

COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information

Technologies, 25, 5261 – 5280. https://doi.org/10.

1007/s10639-020-10219-y

Bedenlier, S., Wunder, I., Glaser-Zikuda, M., Kammerl, R.,

Kopp, B., Ziegler, A., & Handel, M. (2021).

“Generation invisible”?: Higher education students’

(non)use of webcams in synchronous online learning.

International Journal of Educational Research Open,

2,100068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100068

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in

psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2),

77 – 101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Cho, H., Rivera-Sanchez, M., & Lim, S.S. (2009). A

multinational study on online privacy: global concerns

and local responses. New Media and Society, 11(3), 395

– 416. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444808101618

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R.

(1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A

comparison of two theoretical models. Management

Science, 35(8), 982–1003.

Emami-Naeini, P., Francisco, T., Kohno, T., & Roesner, F.

(2021). Understanding privacy attitudes and concerns

towards remote communications during the COVID-19

pandemic. Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security

(SOUPS ‘21) (online only). USENIX.

Gherhes, V., Simon, S., & Para, I. (2021). Analysing

students’ reasons for keeping their webcams on or off

during online classes. Sustainability, 13, 3203.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063203

UK Students’ Concerns About Security and Privacy of Online Higher Education Digital Technologies in the Coronavirus Pandemic

491

Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). (2022a). HE

student enrolments by level of study 2016/17 to

2020/21. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/

sb262/figure-3.

Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). (2022b).

What do HE students study? https://www.hesa.

ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/what-study.

Khalid, F., Daud, M.Y., Rahman, M.J.A., & Nasir, M.K.M.

(2018). An investigation of university students’

awareness of cyber security. International Journal of

Engineering & Technology, 7(4.21), 11 – 14.

Kim, E.B. (2013). Information security awareness status of

business college undergraduate students. Information

Security Journal: A Global Perspective, 22(4), 171 –

179. https://doi.org/10.1080/19393555.2013.828803

Kim, S.S. (2021). Motivators and concerns for real-time

online classes: focused on the security and privacy

issues. Interactive Learning Environments,

https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1863232.

Müller, A.M., Goh, C., Lim, L.Z., & Gao, X. (2021).

COVID-19 emergency elearning and beyond:

experiences and perspectives of university educators.

Education Sciences, 11, Art. 19. https://doi.org/

10.3390/educsci11010019

National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC): What is cyber

security? https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/ section/about-

ncsc/what-is-cyber-security

Oesch, S., Abu-Salma, R., Diallo, O., Krämer, J., Simmons,

J., Wu, J., & Ruoti, S. (2020). Understanding user

perceptions of security and privacy for group chat: a

survey of users in the US and UK. Proceedings of

Annual Computer Security Applications Conference

(ACSAC ’20). ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/

3427228.3427275

Petrie, H., & Merdenyan, B. (2016). Cultural and gender

differences in password behaviors: Evidence from

China, Turkey and the UK. Proceedings of the 9th

Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

(NordiCHI ’16). ACM Press. https://doi.org/10.1145/

2971485.2971563

Rosnow, R. L. & Rosenthal, R. (2012). Beginning

behavioral research: a conceptual primer (7th edition).

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Schatz, D., Bashroush, R., & Wall, J. (2017). Towards a

more representative definition of cyber security.

Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law, 12(2),

Art 8. https://doi.org/10.15394/jdfsl.2017.1476

Serhan, D. (2020). Transitioning from face-to-face to

remote learning: students’ attitudes and perceptions of

using Zoom during COVID-19 pandemic.

International Journal of Technology in Education and

Science, 4(4), 335 – 342.

Siegel, S., & Castellan, N.J. (1988). Nonparametric

statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill.

Slusky, L. & Partow-Navid, P. (2014). Students’

information security practices and awareness. Journal

of Information Privacy and Security, 8(4), 3 – 26.

https://doi.org/10.1080/15536548.2012.10845664

Steinberg, J. (2019). Cybersecurity for dummies. Wiley.

Trepte, S., Reinecke, L. Ellison, N.B., Quiring, O., Yao,

M.A. & Ziegele, M. (2017). A cross-cultural

perspective on the privacy calculus. Social Media +

Society, 3(1), 1 – 13. DO https://doi.org/10.1177/

2056305116688035

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization (UNESCO). (2021). COVID-19:

reopening and reimagining universities, survey on

higher education through the UNESCO National

Commissions. unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf00003

78174.

Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J.

(2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK

universities: afflictions and affordances of emergency

online migration. Higher Education, 81, 623 – 641.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Windley, P.J. (2005). Digital identity: unmasking identity

management architecture. O’Reilly.

CSEDU 2023 - 15th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

492