Safety Education Method for Older Drivers to Correct

Overestimation of Their Own Driving

Akio Nishimoto

1

, Rinki Hirabayashi

1

, Hiroshi Yoshitake

1a

, Kenichi Yamasaki

2

, Genta Kurita

2

and Motoki Shino

1

1

Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, 5-1-5 Kashiwanoha, Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan

2

Mitsubishi Precision, Co., Ltd., 345 Kamimachiya, Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan

{kyamasaki, genta}@mpcnet.co.jp, motoki@k.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Keywords: Older Drivers, Safety Education, Overestimation, Optimism.

Abstract: Older drivers tend to overestimate their driving ability. This overestimation makes it difficult for them to drive

safely. We considered why older drivers formed their overestimation and proposed a safety education method

to correct it. The proposed method includes simulated experiences of collisions and near-miss events and

reflection on their driving at the events. The proposed method was found effective for older drivers to correct

their overestimation based on a participant experiment. However, compared to non-older drivers, the older

drivers corrected their overestimation less. To investigate the reasons for this result, we analysed the method’s

effectiveness on older drivers. Analysis results suggest that the optimistic interpretation of their own driving

discourages older drivers from correcting their overestimation.

1 INTRODUCTION

In many countries, the number of older licenced

drivers is rapidly increasing (Newnam et al., 2020).

Especially in Japan, the number of older licenced

drivers has increased ten times in the last ten years,

and the ratio of traffic accidents caused by them has

increased drastically (Japanese police department,

2019). Therefore, traffic accidents by older drivers

have become an urgent issue that must be solved.

Countermeasures to prevent traffic accidents by

older drivers include promoting the return of driver’s

licences, developing autonomous driving technology

or advanced driver-assistance systems, and driver

education. However, driving a car is essential to live

for some older people (Yanagihara 2019). Thus,

promoting the return of their licence greatly impacts

their quality of life. Moreover, even if autonomous

driving technology and driver-assistance system are

used, drivers still need to drive most of the time on

their own for now. Accordingly, improving the

effectiveness of safety education is important to

reduce traffic accidents by older drivers.

One of the important aspects of safe driving for

older drivers is self-assessment of their own driving.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6875-0957

Although the decline in driving ability may be

inevitable due to cognitive and physical decline with

age, if older drivers can correctly identify their driving,

older drivers can drive safely (Anstey et al., 2005).

Meanwhile, most older drivers are overconfident in

their driving ability (Ota et al., 2004). Therefore, safety

education, which lets older drivers estimate their real

driving ability and correct their overestimation, is

important for them to drive safely.

The overestimation of drivers is said to be formed

by their daily driving experience. Concretely, drivers

do not often encounter accidents or near-miss events,

even if they drive dangerously (Matsumura, 2011).

Moreover, if drivers experience collisions or near-

miss events, they often do not reflect them in their

driving by considering them exceptions or blaming

other traffic factors (Job, 1990). In other words,

drivers form their overestimation because they have

few opportunities to correct their overestimation in

their daily driving, and even if they face such events,

the events alone do not lead them to correct them.

Therefore, safety education considering this

formation process of overestimation is required.

This study proposes a safety education method

that is effective for older drivers to correct their

326

Nishimoto, A., Hirabayashi, R., Yoshitake, H., Yamasaki, K., Kurita, G. and Shino, M.

Safety Education Method for Older Drivers to Correct Overestimation of Their Own Driving.

DOI: 10.5220/0011804900003417

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2023) - Volume 2: HUCAPP, pages

326-334

ISBN: 978-989-758-634-7; ISSN: 2184-4321

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

overestimation of their own driving. To achieve this

goal, we considered why drivers formed their

overestimation, developed methods to correct it, and

verified and discussed the method’s effectiveness for

older drivers.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2

describes and proposes the education method which

aims for older drivers to correct their overestimation.

Section 3 describes the experimental method to verify

the effectiveness of the proposed method for older

drivers. Section 4 describes the experiment’s results

showing whether the proposed method was effective.

Section 5 discusses the effectiveness of the proposed

method. Lastly, Section 6 summarizes the findings of

this study.

2 EDUCATION METHOD

In this study, two points that form overestimation in

driving were focused on: lack of experiences of

collisions and near-miss events and difficulty in

reflecting such experiences in their own driving. Thus,

an education method was developed which meets the

following two requirements:

• Enable drivers to experience collisions and near-

miss events

• Enable drivers to reflect collisions or near-miss

events in their own driving

The following two sections (Sections 2.1 and 2.2)

describe the method that satisfies the requirements.

2.1 Experience Collisions or Near-Miss

Events

A driving simulator was used to have participants

experience collisions and near-miss events because

simulators can reproduce such events safely. The

scenario where drivers pass through a narrow street

with blind corners and pedestrians running out from

the corners was chosen as the simulation scenario

(Figure 1). This scenario was chosen because older

drivers are more likely to cause accidents in this

scenario.

When using simulators in education, it is

important to make the participants think that the

simulated experience is reasonable and can imagine

their problems (Nakamura, 2007). First, to make the

participants think that the simulated collisions or

near-miss events are reasonable, participants are

given the experience of collisions or near-miss events

based on their own driving by the following steps.

Figure 1: A sample scenario reproduced inside the driving

simulator that the participants experience.

1. Participants drive a simulator course without

pedestrians running out from the blind corners,

and their driving behaviour is recorded.

2. Participants watch the driving behaviour

recorded in the 1st step from the first-person’s

perspective using the simulator, and a pedestrian

runs out from a certain blind corner.

Pedestrians running out from the blind corners

were set to start moving 1.2 seconds before the

vehicle reached the pedestrian to reproduce a risky

situation. By having the participants experience the

events based on their own driving behavior, they were

likely to think that the collisions or near-miss events

could happen in their real driving.

Second, to enable the participants to imagine what

is problematic through the simulated experience, we

focused on what task is done during driving and to

simplify the driving task. When drivers sense danger

in the traffic environment, they first detect hazards

that may cause danger (Hazard perception) and

estimate the risk of the hazard (Risk perception)

(Shino et al., 2012). Thus, we created two types of

scenarios that focus on each of them respectively to

make the driving task simple. In the hazard-

perception scenario, an alarm rings before the

pedestrian runs out so that the participants can focus

on detecting hazards by estimating the risk of hazards

high compulsory. In the risk-perception scenario, a

red mark was placed above all hazards that may run

out so that the participants could focus on estimating

the risk of hazards by enabling compulsory detection

of hazards. In this way, when the participants

experienced collisions or near-miss events in the

simulated driving, they were promoted to consider the

cause of the events and reflect on the problem of their

driving behaviour. The method’s effectiveness in

giving participants experience of collisions and near-

miss events by dividing into these two scenarios has

already been validated in our previous work

(Nishimoto et al., 2021).

2.2 Reflect Collisions or Near-Miss

Events in Their Own Driving

In this study, the coaching method, which is

sometimes used in driving education, was adopted.

Safety Education Method for Older Drivers to Correct Overestimation of Their Own Driving

327

Unlike teaching, this method encourages students to

realize their driving problems voluntarily through a

dialogue about their driving between them and their

coaches. This method was proven effective in

correcting self-assessment (Renge et al., 2010). Thus,

we let the participants speak with the experimenter

about the experiences of collisions or near-miss

events in the simulator based on this method to

promote them to realize their driving problem. To

learn lessons that can be applied in real life from

simulated near-miss events, Nakamura (2007) points

out that the following three points are important:

(a) Whether the students recognize the simulated

experiences as a near-miss event

(b) Whether the students understand the cause of

the near-miss event

(c) Whether students acquire measures that can be

used in actual situations

Based on these points, in this study, we had the

participants answer the following three questions just

after the simulated experiences of collisions or near-

miss events to promote them to learn lessons from

experience:

(a) How did you recognize this situation with a

pedestrian running out from a blind corner?

(b) What do you think caused this collision or

near-miss event?

(c) Have you ever experienced a similar situation

in the past?

This coaching method lets the participants think

and answer these questions voluntarily. However, for

question (b), the experimenter sometimes assists them

in thinking about the cause of the experience (e.g.,

“Did you detect the pedestrian fast?” or “How was the

speed of the car?”). In addition, for question (c), the

experimenter encouraged the participants to recall

and answer concrete situations if they had a similar

experience in the past.

3 EXPERIMENT METHOD

A between-subjects design experiment was conducted

to verify the effectiveness of the education method for

older drivers proposed in the previous section. The

method’s effectiveness was evaluated regarding the

change in self-estimation (overestimation) and on-road

driving behaviour. The details are described in the

following sections. This experiment was conducted

with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the

University of Tokyo.

3.1 Participants

The participants were 20 older participants and 20

non-older participants for comparison. The older

participants were recruited from a human resource

centre that offers a temporary jobs to older residents

in Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan. All of them were 70 years

or older (mean age = 74.1, SD = 3.0), driving

routinely (mean number of days per week to drive =

5.5, SD = 1.9), and had no cognitive impairment. The

non-older participants who live or work near the

Kashiwa Campus of The University of Tokyo were

recruited. They aged between 26 to 46 years (mean

age = 41.5, SD = 6.0) and driving routinely (mean

number of days per week to drive = 5.3, SD = 2.3).

3.2 Equipment

Figure 2 shows the driving simulator used in this

study. The scenario inside the simulator was created

with the simulator software D3sim (Mitsubishi

Precision Co., Ltd.). During the simulator driving, the

eye movements of the participants were measured

with a glass-type eye-tracking device (Tobii Pro

Glasses 2, Tobii AB). This eye movement data is used

to identify when the participants detected the

pedestrian running out from the blind corners in the

simulator scenario.

An experimental vehicle equipped with a data

recorder was used to evaluate the on-road driving

behavior. The recorder recorded vehicle behaviour

(e.g., position, speed, acceleration), driver operation

(e.g., steering wheel angle, pedal status), and images

acquired from cameras equipped inside the vehicle

(e.g., vehicle front view, driver’s face).

3.3 Outcome Measures

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method,

we evaluated the change in self-estimation and on-

road driving behaviour. Moreover, to examine

whether the proposed education method was effective

for the participants to correct their overestimation,

their reflection on the simulated experiences was also

evaluated. To assess these, we adopted the following

three outcome measures.

3.3.1 Self-Estimation

To evaluate the change in self-estimation, we made a

questionnaire with the following four items. Each

item was scored on a 7-point Likert scale.

1. Are you aware enough of hazards during

driving?

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

328

2. Are you capable of detecting hazards during

driving?

3. Are you able to sufficiently estimate risks of

hazards during driving?

4. Are you driving safely overall?

Figure 2: Appearance of driving simulator.

In addition, the participants were ordered to score

each item from absolute and relative perspectives

because drivers often overestimate themselves

compared with other drivers (Matsuura, 1999). An

average of the eight (four items * two perspectives)

scores was set as the self-estimation score. When the

participants scored, they were shown the video of

their on-road driving before the education (described

in the next section) and evaluated that driving to

clarify what driving to evaluate. During the on-road

driving before the education, a driving instructor sat

in the passenger seat and answered the same

questionnaire based on the driving of each participant.

Using the two scores, we set the overestimation score,

which is calculated for each participant by subtracting

the instructor’s score from the participant’s score to

evaluate the change in self-estimation.

3.3.2 On-Road Driving Behaviour

An on-road driving experiment was conducted before

and after the education to evaluate the changes in on-

road driving behaviour. The participants drove a

course set near the campus, which included narrow

streets and intersections with blind corners like the

simulator scenario.

As a target scenario inside the on-road driving to

evaluate the change in driving behaviour, we adopted

a scenario where the participants drive through a stop

intersection with a blind corner (Figure 3). At stop

intersections, it was found that older drivers tend to

drive faster near the stop line and confirm less

towards the left and right when passing the

intersection compared to middle-aged drivers

(Hashimoto et al., 2010). Thus, in this study, we set

the speed when passing the stop line and the ratio of

time spent to confirm towards the left and right when

passing the intersection (confirmation time ratio) as

measures to evaluate on-road driving behaviour.

Figure 3: Appearance of target scenario in on-road driving:

Stop intersection with blind corners.

Figure 4: Experimental procedure.

3.3.3 Reflection on the Simulated

Experiences

To evaluate whether the participants reflected the

simulated experiences in their driving, we adopted the

following three scores: Recognition, Understanding,

and Acquisition. Each was scored based on the

answers to the questions (a) – (c) asked just after

experiencing each simulated scenario mentioned in

Section 2.2.

Recognition score (Answer to question (a))

• 0.0: Recognize it as safe

• 0.5: Recognize it as a near-miss event

• 1.0: Recognize it as a collision

Understanding score (Answer to question (b))

• 0.0: Do not answer driving problems

• 0.5: Answer driving problems with assist

• 1.0: Answer driving problems voluntary

Acquisition score (Answer to question (c))

• 0.0: Do not answer past experiences

• 0.5: Only answer the presence of past

experiences.

• 1.0: Answer the concrete situation of past

experiences.

3.4 Procedure

The experiment was conducted over three days, and

each day was spaced for about one week (Figure 4).

On Day 1, the participants are explained about the

nature of the experiment, drive the simulator to create

customized risky scenarios for education, and drive

on roads. On Day 2, the participants experience the

proposed education method and drive on roads again

after the education. Finally, on Day 3, the participants

Safety Education Method for Older Drivers to Correct Overestimation of Their Own Driving

329

answered the self-estimation questionnaire, drove on

roads, and underwent some cognitive function tests,

which were conducted only on older drivers.

In the education, the participants answer the self-

estimation questionnaire and experience the scenarios

in the simulator. Each participant experienced four

scenarios (two hazard-perception scenarios and two

risk-perception scenarios). First, the participants

answer the self-estimation questionnaire before they

experience any scenarios. Second, they experience

two hazard-perception scenarios, and after each

scenario, they answer the questionnaire and review

their self-estimation score about detecting hazards.

Third, they experience two risk-perception scenarios,

answer the questionnaire, and review their self-

estimation score about estimating risk similarly.

Finally, after experiencing all four scenarios, answer

the questionnaire again and review their self-

estimation score about safety awareness and overall

safety of their driving behaviour.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Self-Estimation

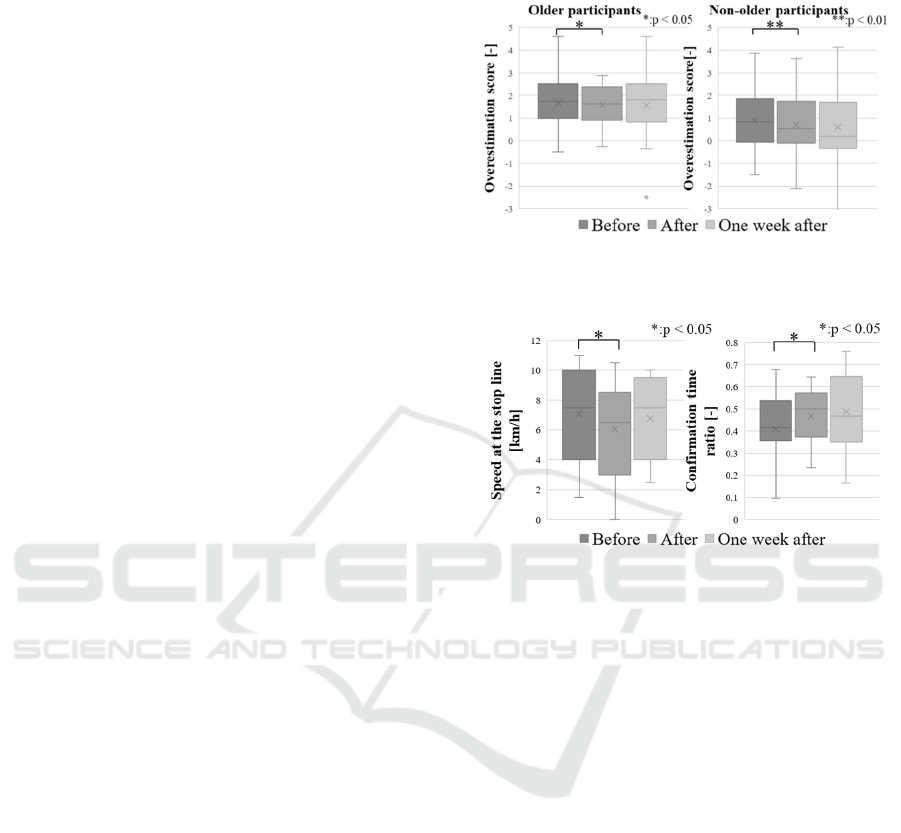

The overestimation score decreased significantly

after the education for both older and non-older

participants (Older: p < 0.05, non-older: p < 0.01)

(Figure 5). Moreover, the mean overestimation score

decreased after the education, and this effect

continued one week after the education. Therefore,

the effectiveness of the proposed education was

confirmed. However, compared to the non-older

participants, the decrease in mean overestimation

score of older participants between before and after

education was small (Older: 0.08, non-older: 0.22). In

addition, the number of older participants who did not

correct their overestimation score was more than the

non-older participants (Older: 6 participants, non-

older: 4 participants). Thus, we confirmed that the

proposed method was less effective for older than

non-older participants.

4.2 On-Road Driving Behaviour

The older participants improved both driving

measures, where the speed at the stop line decreased

and the confirmation time ratio increased after the

education. Moreover, the confirmation time ratio

improvement continued one week after the education,

although the improvement in speed did not (Figure 6).

Therefore, the proposed education was effective in

terms of on-road driving behaviour, reducing unsafe

behaviour at stop intersections.

Figure 5: Change in on-road driving behaviour of older

participants.

Figure 6: Change in overestimation score of older and non-

older participants.

4.3 Reflection on the Simulated

Experiences

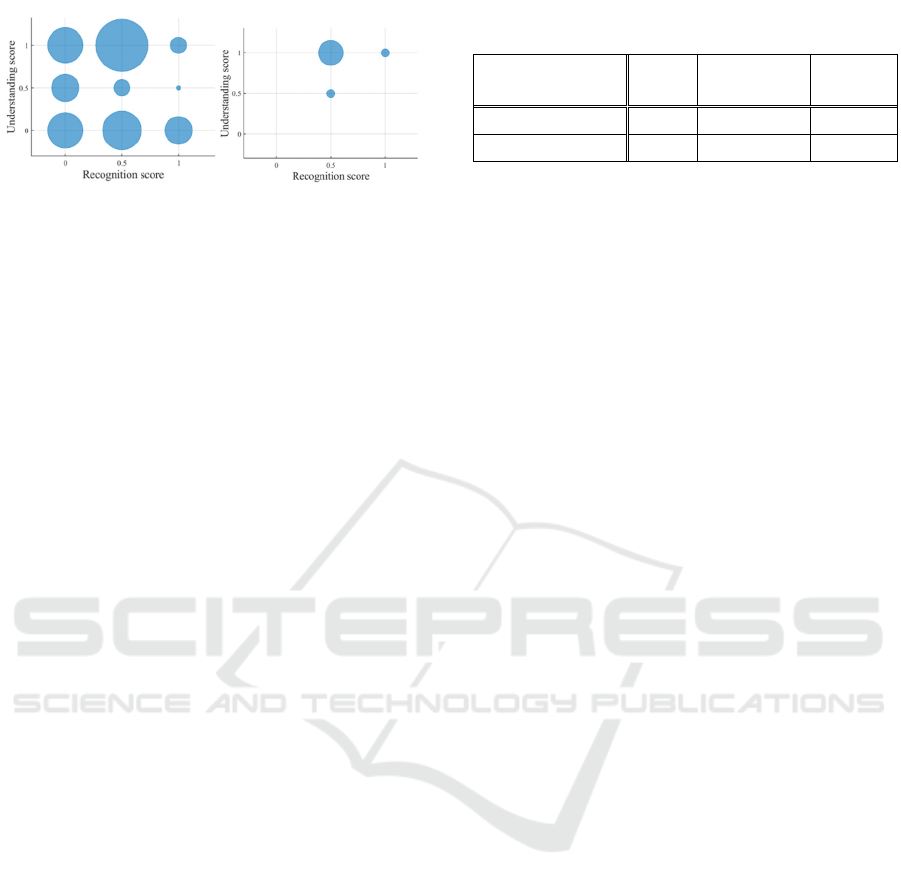

The participants tended to correct their overestimation

if they recognized the simulated experience and

understood the cause of it. We plotted the answered

frequency of each combination of recognition and

understanding scores and classified them into two

groups according to whether the participants corrected

their overestimation score after they answered or not:

correcting and non-correcting (Figure 7). The

acquisition score was excluded from the plot because

it was found that the score had less to do with the

correction of overestimation. This plot showed that

recognizing the situation as near-miss events or

collisions and understanding the cause of the situation

was essential for the participants to correct their

overestimation. Therefore, it was shown that the aim of

the proposed method was appropriate, and if the older

participants behaved as expected, they were likely to

correct their overestimation. On the other hand, we

found that older participants did not recognize the

situation as near-miss events and collisions and did not

reflect such experiences in their own driving.

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

330

Figure 7: Answered frequency of the combinations of

recognition and understanding scores (Left: non-correcting

group, right: correcting group).

5 DISCUSSION

The results show that the proposed education method

effectively corrected the older participants’

overestimation. However, it was also found that the

older participants were less likely to correct their

overestimation and often did not reflect the simulated

experiences in their driving, contrary to our

expectations. Thus, to reveal why the proposed

method was ineffective for some of them and how the

effectiveness of the education could be improved, we

analysed the participants who did not correct their

overestimation and conducted an additional survey.

5.1 Analysis of Non-Correcting

Participants

To investigate why the non-correcting participants

did not correct their overestimation, we classified the

older participants into correcting and non-correcting

groups according to whether they corrected their

overestimation score and investigated the differences.

First, we analysed the difference of whether each

group recognized the situation as near-miss events

and collisions or not. By comparing the recognition

score in each group, the non-correcting group was

less likely to recognize the situation as a near-miss

event than the correcting group (Table 1). Thus, it was

found that the method to enable participants to

experience near-miss events and collisions did not

work as expected for the non-correcting group. We

further analysed the eye movement data to reveal the

reason for this. In the scenarios, pedestrians appeared

1.2 seconds before a collision uniformly. Thus, if the

participants can detect the pedestrian earlier, they can

easily avoid it. To measure this, we defined the

detecting time as an elapsed time after the appearance

of the pedestrian to when the fixation point

overlapped the pedestrian. We compared the

detecting time between the two groups and found that

the average detecting time of the two groups is alike

Table 1: Comparison of recognition score percentage

between correcting and non-correcting groups.

Group

Safe

(0.0)

Near-miss

(0.5)

Collision

(1.0)

Correcting 25% 58% 17%

Non-correcting 63% 25% 12%

(Correcting: 0.35 seconds, non-correcting: 0.34

seconds). In other words, detecting time did not

influence the recognition of the situation. To make

clear why the non-correcting group did not recognize

the situation as a near-miss event, we plotted the

detecting time corresponding to the “safe (0.0)” and

“near-miss event (0.5)” of both groups (Figure 8).

This figure showed that the non-correcting group

never answered “near-miss event” if the detecting

time was less than 0.3 seconds. Moreover, only the

non-correcting group answered “safe” if the detecting

time was more than 0.4 seconds. This result shows

that each group interpreted the simulated experiences

differently. The non-correcting group tended to feel

the experiences as safe, and the correcting group felt

as a near-miss event.

Second, we analysed whether the correcting and

non-correcting groups reflected the experiences

differently after the near-miss or collision

experiences. To investigate this, we analysed the

difference in understanding scores between the two

groups when the recognition score was 0.5 or 1. This

analysis revealed that the correcting group tended to

answer driving problems such as speed and gaze. In

contrast, the non-correcting group tended to answer

the problems of other factors like the simulator

without admitting their own driving problems (Table

2). Thus, the non-correcting group tended to be

reluctant to interpret their own driving problems,

although the correcting group interpreted them

relatively easily.

The analysis showed that even though the non-

correcting participants were given the opportunities

to have near-miss and collision experiences and to

reflect on their driving behaviour, they interpreted

them optimistically and did not correct their

overestimation. Older drivers are known to have the

characteristics to interpret the effects of their driving

optimistically (e.g., Ferring et al., 2015). Such

optimistic characteristics may have prevented the

older participants from correcting their

overestimation and considering it may be important

to improve the effectiveness of the education.

Therefore, it was suggested that it was required to

reveal the impacts of such an optimistic interpretation

on the older participants and correct overestimation.

Safety Education Method for Older Drivers to Correct Overestimation of Their Own Driving

331

Figure 8: Detecting time corresponding to “safe (0.0)” or

“near-miss (0.5)” answers of correcting and non-correcting

groups.

Table 2: Comparison of understanding score percentage

between correcting and non-correcting groups.

Group

Not driving

problems

(0.0)

Driving

problems

(0.5, 1.0)

Correcting 50.0% 50.0%

Non-correcting 16.6% 83.3%

5.2 Additional Questionnaire Survey

The analysis of the non-correcting group suggested

that the optimistic interpretation impacted correcting

overestimation. We investigated the optimistic

characteristics of the older participants through an

additional questionnaire survey to consider how to

improve the effectiveness of education.

5.2.1 Method

An additional questionnaire survey was conducted on

the older participants to investigate whether the non-

correcting group has an optimistic view of their

driving behaviour. In accordance with the self-

estimation score, we adopted two questionaries that

ask optimistic views from an absolute and a relative

perspective. When they did not correct their

overestimation from an absolute perspective, they

may not have been able to admit their driving ability

declining with age. In a previous work (Ferring et al.,

2015), drivers were asked how much they agreed with

positive stereotypes (e.g., more experience, more

reasonable) and negative stereotypes (e.g., more

dangerous, more error-prone) about older drivers in a

five-point scale questionnaire. The more the drivers

were older, the more likely they were to agree with

positive stereotypes and disagree with negative

stereotypes. This indicates that older drivers tend to

interpret the decline of their driving ability

optimistically. Therefore, we adopted the

questionnaire used in this Ferring’s work and had the

participants answer it. We verified the optimistic

interpretation of their driving ability and considered

Figure 9: Results of the Ferring’s questionnaire.

Figure 10: Results of the Gosselin’s questionnaire.

whether such an interpretation affected the correction

of overestimation.

When the participants did not correct their

overestimation from a relative perspective, they may

not have been able to accept being poor in their

driving ability compared to others. A previous work

(Gosselin et al., 2010) revealed that when the older

drivers assessed the risk of a car crash in other older

and middle-aged drivers in a five-point scale

questionnaire, they answered that the risk is higher in

both drivers compared to themselves. This indicates

that older drivers are likelier to interpret their accident

risk than others optimistically. Therefore, we also

adopted Gosselin’s questionnaire and had the older

participants answer it.

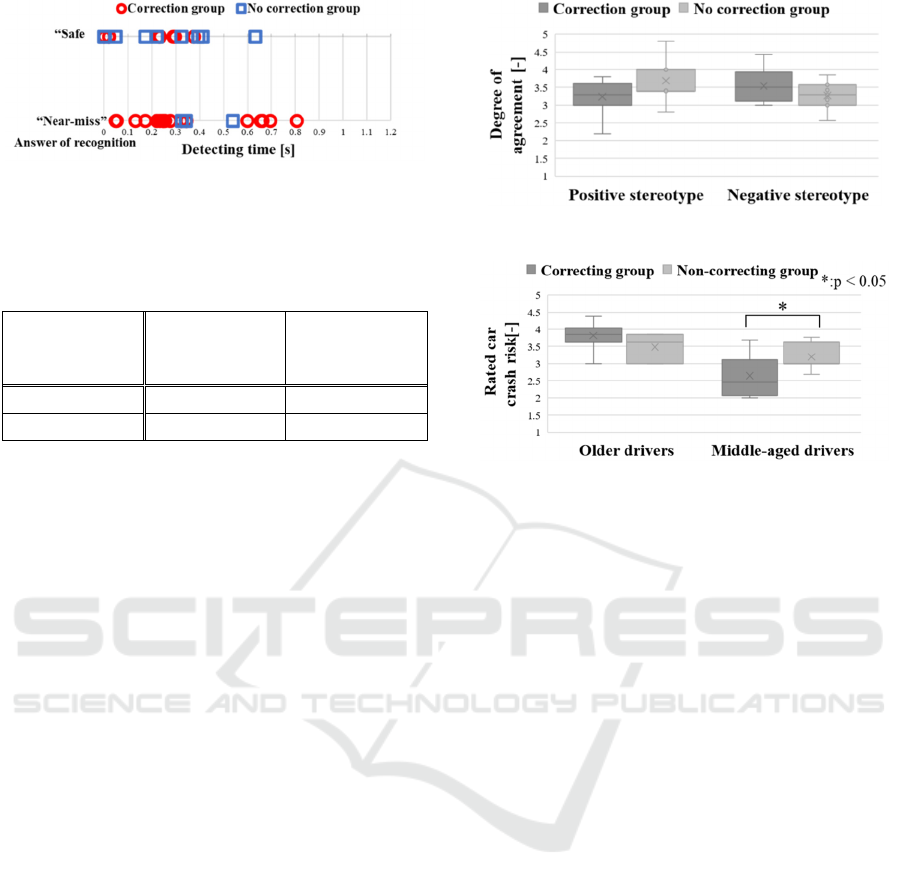

5.2.2 Results and Discussion

As for the stereotypes about older drivers, the non-

correcting group tended to agree with the positive

stereotypes and disagree with the negative

stereotypes compared to the correcting group (Figure

9). As for the crash risk, the non-correcting group

assessed that the risk in middle-aged drivers was

higher compared to the correcting group (Figure 10).

These results showed that the non-correcting group

tended to interpret their driving and especially the

decline of it with age optimistically. This suggests

that their optimistic interpretation influenced

correcting their overestimation, and improving such

interpretation was the key to correcting their

overestimation.

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

332

In this study, the non-correcting group interpreted

the decline in their driving optimistically, which

meant they were not anxious about their driving

behaviour. This may have made them indifferent to

the education and did not motivate them to change

their belief. This indicates that enhancing participants’

motivation for education may effectively correct

overestimation. In educational technology, Keller’s

ARCS model is known as a measure to enhance

students’ motivation for educational material.

According to this model, improving attention and

relevance to the material is important for students to

be encouraged to try it (Keller, 1987). In this study,

the non-correcting group did not think their driving

needed improvement, which may have impeded them

from having attention and relevance to the education.

Therefore, enhancing attention and relevance to the

education may be the next step to improve the

effectiveness of our method.

5.3 Limitations

There are some limitations in this study. First, the

sample was not large and biased toward active and

healthy males. It is said that male and female older

drivers have different ways of thinking toward their

driving (Ferring et al., 2015). Thus, the effectiveness

of the proposed method for older female drivers may

differ. Second, we did not investigate the long-term

effects of the education, although we checked one

week after the education. We need to continue

investigating the education’s effectiveness because

long-term assessment is important in safety education.

Third, the target scenario in the simulator and on-road

driving was limited to narrow streets and intersections

with blind corners. Older drivers are also likely to

cause accidents in other scenarios. It may not be

obvious that the participants could reflect on their

driving behaviour.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This study proposed an education method to correct

the overestimation of older drivers. This method

enabled the participants to experience near-miss

events or collisions and reflect them in their own

driving. As a result, older people could correct their

overestimation with the method; however, their

correction was less compared to non-older people.

Further analysis and an additional questionnaire

survey revealed that people who did not correct their

overestimation with the method tended to interpret

the simulated experiences and their driving ability

optimistically. It is suggested that this optimistic

interpretation of their driving discouraged them from

correcting their overestimation.

Enhancing the motivation for education is

suggested to be the key to improving the effectiveness

of the education method. The method of enhancing

motivation is fully researched in educational

technology. Therefore, the next step to improve the

method’s effectiveness is to refer to works in

educational technology and consider ways to enhance

the motivation of older participants.

REFERENCES

Anstey, K.J., Wood, J., Lord, S., Walker, J. (2005)

Cognitive, sensory and physical factors enabling

driving safely in older adults: a randomised controlled

trial. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 115, 1-10.

Ferring, D., Tournier, I., Mancini, D. (2015) “The closer

you get…”: age, attitudes and self-serving evaluations

about older drivers. Eur J Ageing. 12, 229-238.

Gosselin, D., Gagnon, S., Stinchcombe, A., Joanisse, M.

(2010) Comparative optimism among drivers: An

intergenerational portrait. Accident Analysis and

Prevention. 42, 734-740.

Hashimoto H., Hosokawa T., Hiramatsu M., Nitta S.,

Yoshida S (2010) Field Survey of a Elderly Driver’s

Behavior at the intersection. Transactions of the Society

of Automotive Engineers of Japan. 41 (2), 527-532.

Japanese police department. (2019) About the

characteristics of the traffic fatal accidents over 30

years in Heisei era.

Job. R. (1990) The application of learning theory to driving

confidence: the effect of age and the impact of random

breath testing. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 22 (2),

97-107

Keller, J. M. (1987) Development and use of the ARCS

model of instructional design. Journal of instructional

development. 10 (2), 2-10.

Matsuura, T., (1999) Drivers’ overestimation of their own

skill. Society of Japanese Psychological Review. 42(4),

419-437.

Matsumura, Y., Tamida, K., Nihei, M., Shino, M., Kamata.,

M. (2011) Proposal of Education Method for Elderly

Drivers Based on the Analysis of their Real Driving

Behavior. The Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers.

20, 321-324.

Nakamura. T. (2007) Anzen kyo-iku ni okeru giziteki na

kiken taiken no kouka to kadai [Effectiveness and

problem of simulated experiences in safety educations].

Japan Society for Safety Engineering. 46(2), 82-88

Newnam, S., Koppel, S., Molnar, L. J., Zakrajsek, J.D, Eby,

D. W., Blower, D. (2020) Older truck drivers: How can

keep them in the workforce as long as safety possible?

Safety Science. 121, 589-593.

Nishimoto. A., Hirabayashi, M., Yoshitake, H., Yamazaki,

K., Kurita, K., Shino, M. (2021) Safety Education for

Safety Education Method for Older Drivers to Correct Overestimation of Their Own Driving

333

Elderly Drivers Based on Self-evaluation Formation

Process. Japan Society Automotive Engineers Autumn

Conference. 128 (21), 1-6.

Ota, H., Ishibashi, T., Oiri, M., Murai, M., Renge, K. (2004)

Self-evaluation Skill among Older Drivers. Japanese

Journal of Applied Psychology. 30 (1), 1-9.

Renge. K., Ota, H., Mukai M., Ogawa, K., (2010)

Effectiveness of Training for Elderly Drivers based on

Coaching Method. Japanese Journal of Traffic

Psychology. 26 (1), 1-13.

Shino, M., Kimura, K., Nihei, M, Kamata, M., (2012)

Analysis on Relation between the Unsafe Driving

Behavior in Actual Environment and the Cognitive

Characteristics of Elderly Drivers. Transactions of the

JSME. 78 (794), 3362-3373.

Yanagihara T. (2015) Koreisya no gaisyutsu hindo kara

mita nitizyouseikatu no-ryoku to idousyudan ni kansuru

kousatu. [Consideration of the effect of frequency of

going out of older people on the means of transportation

and the activities of daily life]. Journal of JSCE. 71 (5),

459-465.

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

334