An Immersive Virtual Reality Application to Preserve the Historical

Memory of Tangible and Intangible Heritage

Lucio Tommaso De Paolis

a

, Sofia Chiarello

b

and Valerio De Luca

c

Department of Engineering for Innovation, University of Salento, Lecce, Italy

fi

Keywords:

Cultural Heritage, 3D Modelling, Virtual Reality, User Experience.

Abstract:

This paper concerns the valorization of a building that has been inaccessible for a long time: the Castle

of Corsano, a small Italian village in the Salento area. Starting from the three-dimensional reconstruction

of the rooms of the Castle and, in part, of its furnishings, it presents the development of a VR application

with the possibility of interacting with the environments of the Palace and learning the historical information

collected not only through bibliographic research but also through an act of remembering, which has involved,

in particular, the elderly of the village. The goal is to create an archive of memory and make virtually accessible

one of the most emblematic historical places of the urban network, which risks being definitively forgotten.

Experimental tests were carried out on a heterogeneous sample of users to evaluate the factors characterising

the sense of presence and the relationships between them. The results revealed a high level of involvement

and perceived visual fidelity.

1 INTRODUCTION

This research work concerns the Castle of Corsano, a

building that has been abandoned and inaccessible to

its inhabitants for over thirty years, located in a small

town on the Adriatic coast of Salento.

Accessibility plays a fundamental role among the

aspects related to the fruition of Cultural Heritage.

However, an increasing number of sites, both archae-

ological and natural, are in a state of abandonment

and neglect or have already been destroyed, often

intentionally. Fragility and degradation of artefacts,

and poor protection or enhancement policies are only

some of the causes that lead to the inaccessibility of a

cultural site.

Therefore, physical access to a place, where there

are no dangers, should be the main objective of her-

itage valorisation policies, with a view to involving

the greatest number of people and creating partici-

pation. However, in cases where the state of preser-

vation is poor, it is sometimes necessary to resort to

other means that become tools for accessibility, or to

flank and support a more traditional fruition. Among

these, information and communication technologies

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1274-9070

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2158-3976

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3018-7251

(ICT) are taking over, ranging from Mixed Reality

(MR) to Virtual Reality (VR).

The aim of the project is twofold: on the one hand,

it aims to preserve the historical memory of the place

through its material and non-material component, by

exploiting the oral testimonies of the women who

worked inside the castle; on the other hand, it aims

to create a dissemination tool by helping to promote

the knowledge of a site to professionals and, above

all, to local people, thanks to VR technology.

The first part of the paper provides a historical

overview of Corsano and its castle from the 12th cen-

tury to the 20th century, with a particular emphasis

on the role of the tobacco factory it assumed until

the 1980s; the second part of the research examines

all the phases of technological development, starting

with the three-dimensional modelling of the places,

up to the realisation of an application usable in VR

through the “Oculus Quest 2” Head-Mounted Dis-

play. This stand-alone visor allows users to enjoy a

VR experience even from home and without neces-

sarily linking it to a computer. It was therefore the

best choice to enhance a totally inaccessible building,

like the Castle of Corsano.

De Paolis, L., Chiarello, S. and De Luca, V.

An Immersive Virtual Reality Application to Preserve the Historical Memory of Tangible and Intangible Heritage.

DOI: 10.5220/0011791400003417

In Proceedings of the 18th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2023) - Volume 2: HUCAPP, pages

279-286

ISBN: 978-989-758-634-7; ISSN: 2184-4321

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

279

2 RELATED WORK

The 1980s and 1990s saw the first technological ex-

periments applied to cultural heritage, limited, how-

ever, only to the 2D virtual reconstruction of de-

stroyed sites, monuments and ancient urban contexts,

and then displaying them on screens, for the purpose

of documentation.

From the end of the 20th century, the Cultural

Heritage sector has begun to increase the use of im-

mersive technologies belonging to the macrocosm of

’Extended Reality’, a collective term for Augmented,

Virtual and Mixed Reality technologies that provide

sensory experiences through various combinations of

real and digital content.

Among the first examples in literature, it is worth

mentioning the virtual restitution of the Renaissance

mansion of Dudley, commissioned by Queen Eliza-

beth II. The reconstruction was based on some exist-

ing ruins, as well as on historical films, written doc-

uments and also a voice that enriched the virtual tour

(Messemer, 2016). It was one of the first examples of

digital storytelling, which is the idea of combining the

art of storytelling with the variety of digital multime-

dia such as audio, images, and video (Robin, 2006).

The use of innovative VR tools and digitisation

activities have facilitated the dissemination of knowl-

edge and access to Cultural Heritage in a more engag-

ing and innovative way (Bekele et al., 2018).

Since the purpose of most cultural applications in

VR is to revive a reality that no longer exists, the topic

of “time travel” has always been among the most pop-

ular, although declined in different ways.

In 2017 a kind of “time travel” was realized from

the Museo Arqueologico Nacional in Madrid, in col-

laboration with Samsung, within the project entitled

“Vive el Pasado”. It was an immersive tour in which

visitors virtually walked through the history of Spain

from Prehistory to the Modern Age, by using 3D vi-

sors like Cardboards (Sànchez Mateos, 2018).

In Italy, if we look at the Salento area where the

Castle of Corsano is located, we find some interest-

ing similar experiences. In particular, “The Medi-

aEvo Project” was a VR project for edutainment in

cultural heritage based on a serious game oriented to-

wards the knowledge of history and society of a me-

dieval town in Salento (De Paolis et al., 2011a). The

project enhanced interactions among historical, ped-

agogical and ICT researchers by means of a virtual

immersive platform for playing and educating. This

platform, through the reconstruction of the old town

of Otranto in the Middle Ages, has permitted the col-

lection of feedback about the questions related to the

educative use of ICT (De Paolis et al., 2011b).

Near Otranto, in 2021, the enhancement of an

underground oil mill in the abandoned Masseria of

Torcito, next to Cannole (Lecce, Italy), was proposed

by means of a VR application and a MR applica-

tion. The former can be used with Cardboard, through

which it is possible to visit the oil mill from the inside

with spherical photos. In the latter the 3D model of

the olive mill is navigable through the technology of

Virtual Portal (De Paolis et al., 2021).

The use of immersive VR for education or train-

ing offers a substantial improvement in the interest of

learning in these environments, facilitating the under-

standing of complex concepts. This has necessitated

the creation of new VR environments specifically for

learning or training (Checa et al., 2020).

In the educational field can also be placed the

project “VirgilTell”, developed in 2021 by the Poly-

technic of Turin, to make virtual accessible the im-

pervious places of the Racconigi Castle in Piedmont,

unreachable due to restoration. The experience ex-

ploited the use of the Oculus Quest visor. The rooms

were modelled using the support of historians to ver-

ify the veracity of the information and visited together

with the characters of the kings Carlo Alberto and Vit-

torio Emanuele II, who guides as a “ghost” the vis-

itors in 1842 and 1920 respectively (Germak et al.,

2021).

In the same domain, another project concerned

the reconstruction of one of the most representative

UNESCO sites of Lombard architecture: Santa Maria

Delle Grazie in Milan, according to the Cloister of

Dead part. By the means of Oculus Rift, users can

discover the transformations of the Cloister over the

centuries (before and after the bombing of World War

II), which are gradually being lost in common mem-

ory. The aim of the research project is to hand down

the historical phases and intangible memory of the

monument to future generations, thanks to the tool of

Virtual Reality (Banfi and Bolognesi, 2021).

On the contrary, the ultimate goal of the applica-

tion developed for the Castle of Corsano is to enhance

a tangible asset, even if closed to the public for much

longer, by using as sources an intangible cultural her-

itage, mostly made up of oral testimonies, and above

all by inserting them as virtual elements to interact

with. All of this has been made usable through a

medium that is also, in itself, intangible: Virtual Re-

ality.

This dichotomy between real and virtual, between

history and memory is the thread running through the

entire project and constitutes its strong point.

Today, the adoption of VR solutions has turned

out to be effective also in the museum world, to react

to the impact of the forced closure of museums due to

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

280

the Covid-19 pandemic. Virtual visits and tours (in-

cluding the Uffizi and the Vatican Museums in Italy)

were highly appreciated by users, temporarily over-

coming the inaccessibility of museums (Gatto et al.,

2021).

VR technology also came to the aid of small lo-

cal realities, such as the Castle of Corsano, not only

to limit the problem of its use during the pandemic

but, more generally, to promote its accessibility while

waiting for physical access to be permitted. In this

scenario, a user experience study was also conducted

using a questionnaire to assess the sense of presence,

defined as the subjective experience of being in a par-

ticular place, independently of where the user is actu-

ally located (Witmer and Singer, 1998).

3 THE CASTLE OF CORSANO

The castle of Corsano was used for different functions

over the centuries.

Although the building has never been the object

of any archaeological, artistic, or architectural study,

further historical research has been carried out on the

basis of the few archival and bibliographic sources

available.

3.1 From the Origins to the 17th

Century

After the Norman domination of the feud of Corsano,

the Castle appeared as a defensive fortress. A pre-

vious thesis on this subject contributed to hypothe-

size the external structure of the fortress in the 15th

century, with the presence of plumb lines, still visi-

ble today in the facade (Ciardo, 2014). As for who

lived there, the Palace passed, first, in the hands of

the Count of Caserta Della Ratta and then of the noble

families of Securo and Cicala. A deed of sale dated

to 1636 described the cession of the Land of Corsano,

including the Castle, to the Capece family, of Campa-

nian origin.

Figure 1: Part of the stucco decorations in the Castle, still

visible today.

Of particular note is the stucco decoration, pre-

served in the rooms of the south side of the Palace

(Figure 1), probably commissioned by Giovanni Tom-

maso Capece, the most active member of the family

in terms of artistic and architectural (Ciardo, 2014).

Another important source is an Inventarium Ered-

itatis written by a notary, dating from the same period,

with the description of the furnishing of the rooms.

The Capece baronate ended in the XIX century,

with the last descendant of the family who married

Giuseppe Galluccio. He turned the baronial residence

into a tobacco warehouse.

3.2 The Tobacco Warehouse

The project of arrangement and modification signed

by Galluccio in 1958 has provided important infor-

mation about the arrangement of spaces, because of

its architectural plan with a descriptive legend.

Moreover, the oral testimonies of the “tabac-

chine”, the women who worked the tobacco inside

the Castle of Corsano during the 19th century, gave us

the possibility to reconstruct the phases of the tobacco

leaves processing, one of the most important and pop-

ular productions of the south in the last century. The

tobacco was imported into Italy from Portugal around

’500, but it gradually ended in the ’80s of the 19th

century, because of the fungus Peronospera.

In that period, the Tagliaferro family bought the

factory of Corsano, without making substantial struc-

tural changes and leaving the tobacco machines inside

the building (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A conveyor belt still inside the Castle, dating from

the last phases of the tobacco factory.

In 2015, the Palace of Corsano was declared of

cultural interest by the Regional Commission of Cul-

tural Heritage of Puglia.

However, a slow process of decay and neglect still

applies today and the access to the Castle continues

to be severely compromised also by the external scaf-

folding.

An Immersive Virtual Reality Application to Preserve the Historical Memory of Tangible and Intangible Heritage

281

4 THE VR APPLICATION

The poor state of conservation of the castle’s rooms

proved to be a critical factor during the work phases,

making it impossible to stay inside them for long pe-

riods of time. Nevertheless, some inspections inside

the Castle and some photographic acquisitions were

carried out in order to model in a realistic way the an-

cient halls and the furniture, and to design the whole

storytelling, before the development of the VR appli-

cation.

4.1 The Design of the Experience

The established storyboard concerns the reconstruc-

tion of the Castle’s environments in its three main pe-

riods of occupation:

• the 15th century, when it is hypothesized that the

castle of Corsano was a little fortress with plumb

line in the facade, sold to the count of Caserta.

Since there is no documentation regarding the in-

ternal partitioning of the rooms of that period, it

was decided to make it visitable only from the out-

side (Figure 3);

• the 17th century that saw the building as the

main residence of the baronial family Capece,

who commissioned stucco decorations in the halls

(Figure 4);

• the 20th century when the castle was transformed

into a tobacco warehouse (Figure 5) and a lot of

employed women worked inside.

Unlike the fortress, the fruition of the ’700 and ’900

takes place inside the rooms, giving the possibility to

the user to interact with pop-ups, photos and informa-

tion panels.

According to this design idea, the application

starts by default in a corridor with the user’s position

facing a doorway on which an old map is affixed that

allows the temporal switch between the three eras.

This corridor connects the rooms referring to 1700

and 1900, respectively a room decorated with a stucco

Figure 3: 3D model of the hypothetical fortress in 15th cen-

tury.

Figure 4: 3D model of one baronial bedroom in the Castle

during the 18th century.

Figure 5: Reconstruction of the main hall of the Castle

where tobacco was processed in the early 1900s.

vault for the baroque period, and the main room con-

sidered the main environment of the tobacco factory,

together with the adjacent rooms, probably the dress-

ing rooms of the workers.

4.2 The 3D Modelling Phase

Once the experience of the VR application was

designed, it started modelling the environments in

Blender. It is a free and cross-platform 3D modelling

software, which also allows rendering and animation

of 3D objects.

The first step focused on the reconstruction of the

walls, thanks to the main information from the plans

of the land register found in the public archive.

In the second phase, all the furnishings were mod-

elled: for example, we followed the descriptions re-

ported in the Inventarium for the 18th century, while

for the 19th century furniture, the reconstructions of

the tobacco machines were based on the workers’ in-

terviews.

Once the mesh was ready, we texturized every-

thing using the images acquired inside the Castle as

references (Figure 6).

The same textures were also exploited for the

modelling of the eighteenth-century stucco vault, to

obtain the three-dimensional photogrammetric model

of the vault, in the Agisoft Metashape Professional

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

282

Figure 6: Comparison between a photo showing the press

still in the Castle and its 3D reconstruction.

software. This software creates a dense cloud of

points and a mesh with textures until obtaining a very

realistic model, then imported into Blender.

Photogrammetry is a surveying technique that al-

lows to reconstruct and define the position, shape and

size of objects, using the information contained in ap-

propriate photographic images of the same objects,

taken from different points (Cannarozzo et al., 2012).

The whole realised three-dimensional environ-

ment was exported in ".fbx" format to be imported

into the Unity software.

4.3 The Implementation in Unity

The development of the VR application for the Castle

of Corsano had to deal with various aspects, from the

management of the user’s movements in the virtual

world to the presentation of content through sounds

and illustrative pop-ups.

4.3.1 Device and Software Settings

The Oculus Quest 2 Head-Mounted Display (HMD)

turned out to be the most congenial device to safety

run the VR app since it is equipped with the

“Passthrough+" system that guarantees the free move-

ment of the user, without colliding with real objects

during the experience.

To configure the HMD on Unity (a cross-platform

graphics engine) it was necessary to associate the in-

puts from the user movements and rotation to the con-

trollers of the Quest 2, installing the Open XR plug-in

from Unity. Open XR is an open royalty-free standard

that aims to simplify the development of Augmented

and Virtual Reality applications by allowing develop-

ers to easily move between a wide range of AR/VR

devices, including, also, the Oculus Quest 2. In or-

der to manage Open XR, it was necessary to install

the XR plug-in management packages and the XR In-

teraction Toolkit, which contains a set of preset ac-

tions connected by default to certain buttons on Ocu-

lus controllers.

4.3.2 User Interactions

The interactive component and the tracking of the

player’s movement are at the base of the described ap-

plication, as both have a significant impact on the ex-

perience in the virtual environment. Studies confirm

that, compared to gesture-based touchless devices,

controllers connected to visors reveal a better usabil-

ity, also influencing the user’s perception of immer-

sion in VR (De Paolis and De Luca, 2020)(De Paolis

and De Luca, 2022).

For the user’s movement, the “teleportation area”

system was chosen: as soon as the controller ray in-

tercepts the floor, it turns white and allows the user

to move to the exact point where it ends, by pressing

the grip button of the controller. This kind of teleport

enables the free exploration of the virtual world.

To increase immersion in the VR experience, in

all the three virtual worlds the user is given the op-

portunity to interact with pop-ups or panels showing

historical content that contextualizes the objects in the

environments and some vintage photographs.

Moreover, since the main aim of the project is

to integrate part of the tangible cultural heritage

(archival documents and previous thesis work), with

much of the intangible heritage (consisting of folk

songs, interviews and memories of the village), dur-

ing the VR experience in the 19th century the user can

also listen to the voices of some tobacco workers in-

terviewed, accompanied by animations and music in

background (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Visualization of an interactive panel in which

users can listen to the oral testimonies.

5 USER EXPERIENCE

EVALUATION

Various studies have been proposed on the reliabil-

ity of questionnaires for assessing the user experi-

ence in virtual environments and their actual ability

to represent the sense of presence (Schwind et al.,

2019). The Presence Questionnaire (PQ) (Witmer and

An Immersive Virtual Reality Application to Preserve the Historical Memory of Tangible and Intangible Heritage

283

Singer, 1998) has the lowest variance, which denotes

good reliability, probably due to the large number of

items, but the iGroup Presence Questionnaire (IPQ)

(Schubert et al., 2001) seems to be the one that best

represents presence (Schwind et al., 2019).

Nonetheless, the PQ questionnaire was chosen for

the present study in order to take advantage of its

more articulated structure that allows for the evalu-

ation of the effect of multiple factors and the rela-

tionships between them. In particular, a variant of

this questionnaire proposed by the Laboratoire de Cy-

berpsychologie de l’UQO was chosen, consisting of

22 items (plus two optional items for applications that

include haptic feedback), for each of which a rating

is given on a scale of 1 to 7. This version of the

questionnaire was further modified for the testing of

the considered application by replacing the last two

questions on the identification and localisation of en-

vironmental sounds with "Were you able to under-

stand the tabacchine’s stories?", given the importance

of oral testimonies in the entire project. The item

"How compelling was your sense of objects moving

through space?" was removed because no significant

object movement was implemented in the described

VR application. Two further items were added to ask

whether the user has already visited the castle in per-

son, and if so, whether he or she finds the virtual re-

construction faithful to the real castle.

The test was administered to a total of 31 users

aged between 17 and 60 without previous experience

with Virtual Reality. Each user filled in the question-

naire after a few minutes of experience through the

three eras reconstructed by the virtual application.

According to (Witmer et al., 2005), the question-

naire items can be aggregated into the following fac-

tors:

• Involvement, which is a psychological state trig-

gered by how much energy and attention is fo-

cused on the activities in the VR environment.

This may depend on other factors such as personal

thoughts and concerns, the stability of the visor on

the head or the quality of the audio that may neg-

atively affect a proper engagement in the virtual

world;

• Interface Quality, which includes possible dis-

tractions caused by poor video resolution or con-

trollers during the experience;

• Adaptation/Immersion, which is the perception of

being fully immersed in the virtual world by in-

teracting with it. This component increases with

isolation from the physical environment, with the

sensation of natural movement even in the 3D en-

vironment;

• Visual Fidelity, which refers to the viewpoints

one can assume when navigating in the three-

dimensional reconstruction (e.g. the possibility of

looking at objects more closely), and how closely

they reflect those in reality.

In the case study of the Castle of Corsano, a fifth fac-

tor was added, called Understanding Stories, which

corresponds to the item on the ability to understand

the stories told by the tabacchine.

The mean values and the standard deviations of

the scores (between 0 and 6) of the components iden-

tified above, represented in the histogram in Fig-

ure 8, showed a clear convergence of user opinions

towards high levels of Involvement and Visual Fi-

delity. This may partly depend on the novelty effect

of VR environments, which usually helps to produce a

higher level of user satisfaction along with the hands-

on learning strategy typical of serious games (Checa

et al., 2021). Users generally spend a longer time

in adapting themselves to a virtual environment, but,

once they get familiar with it, they enjoy all the op-

portunities offered by VR (Checa et al., 2021).

Figure 8: Histogram showing mean and standard deviation

values for each PQ factor.

The lowest values are referred to the Interface

Quality, though there is great variability in the scores

for this factor, probably caused by a different predis-

position of each user to the VR technologies accord-

ing to their personal attitudes.

The five users who had already visited the castle

in person gave an average score of 5.9 out of 6 for the

fidelity of the virtual reconstruction.

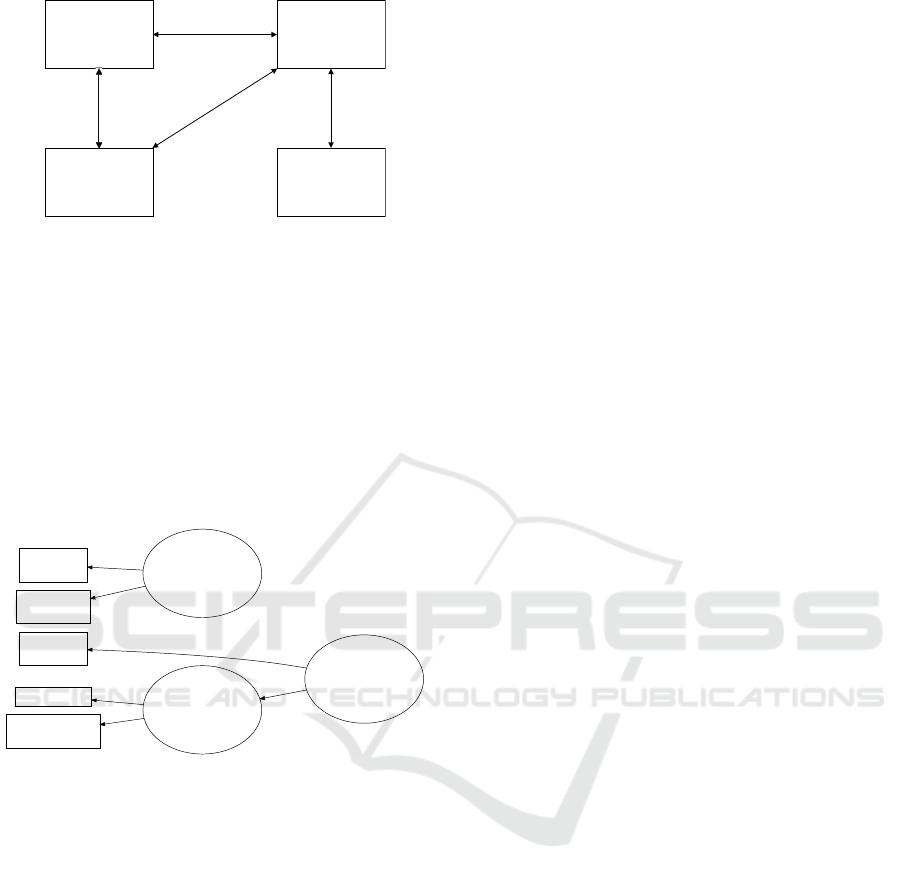

The study presented in (Witmer et al., 2005) on

PQ factors identified the correlations depicted in the

diagram in Figure 9, where Sensory Fidelity repre-

sents a combination of Visual and Audio Fidelity (Wit-

mer et al., 2005).

For the considered case study, a cluster analysis

was conducted through ICLUST, a package for the R

environment based on a hierarchical algorithm (Rev-

elle, 1978) that tries to maximize internal consistency

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

284

Involvement

Adaptation/

Immersion

Sensory

Fidelity

Interface

Quality

Figure 9: Correlations between PQ factors according to

(Witmer et al., 2005).

and homogeneity. A model based on two clusters was

chosen, as it maximizes cluster fit and pattern fit and

minimizes the root-mean square radius (RMSR). The

result is depicted in the diagram of Figure 10, where

ovals represent clusters between items. Cronbach’s

alpha (Cronbach, 1951) and Revelle’s beta (Revelle,

1979) inside each oval represent internal consistency

and scale homogeneity respectively: as these values

tend to coincide in the considered scenario, the clus-

ters can be considered reliable.

Involvement

Interface

Quality

Adaptation/

Immersion

Visual

Fidelity

Understanding

Stories

C1

alpha= 0.75

beta= 0.75

N= 2

0.78

0.78

C2

alpha= 0.54

beta=

0.54

N=

2

0.66

0.66

C3

alpha= 0.79

beta=

0.77

N=

3

0.83

0.83

Figure 10: Cluster fit = 0.72, Pattern fit = 0.99, RMSR =

0.06.

While Sensory Fidelity is correlated with Involve-

ment and Adaptation/Immersion in (Witmer et al.,

2005), in the considered scenario Visual Fidelity is

correlated with Involvement and Understanding Sto-

ries. Involvement is more strictly correlated with the

ability to understand stories, with which it forms a

cluster, than with Visual Fidelity: this highlights the

greater importance of the audio component for un-

derstanding the context, which in turn is crucial for

keeping the user’s attention.

Neither Visual Fidelity nor the ability to under-

stand stories, which could be considered as an au-

dio component of Sensory Fidelity, is correlated with

Adaptation/Immersion, which in turn is only weakly

correlated with Interface Quality and not with In-

volvement.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The goal of the project is to raise awareness among

the citizens, especially the inhabitants of Corsano and

its surroundings, towards the enhancement of the ter-

ritory and the local artistic heritage not included in the

mainstream visit circuit, because of their peripheral

geographical location or because of bad management

upstream.

VR could be the most congenial tool to reach a

wide range of target users. Therefore, the strategy is

to exploit Virtual Reality as a tool for accessibility to

cultural heritage, in its dual meaning. Traditionally,

the term “Cultural Heritage” has referred only to tan-

gible heritage, such as monuments, buildings, and ob-

jects. Later, the definition of the term was expanded

to also include intangible cultural heritage, which in-

volves the traditions and oral expressions of a com-

munity passed down from generation to generation

(UNESCO-ICH, 2003). The evolution of the Castle of

Corsano over the centuries has been available thanks

to the information received from several sources in

order to produce a hybrid combination of historical

research and technology. This dichotomy between

real and virtual, between history and memory is the fil

rouge of the entire project, which becomes its strong

point.

This paper encourages future more analytical re-

search on the building, although the hope remains to

make the castle physically accessible again.

REFERENCES

Banfi, F. and Bolognesi, C. (2021). Virtual Reality for Cul-

tural Heritage: New Levels of Computer-Generated

Simulation of a Unesco World Heritage Site. Springer

Tracts in Civil Engineering, pages 47–64.

Bekele, M., Pierdicca, R., Frontoni, E., Malinverni, E., and

Gain, J. (2018). A survey of augmented, virtual, and

mixed reality for cultural heritage. Journal on Com-

puting and Cultural Heritage, 11(2).

Cannarozzo, R., Cucchiarini, L., and Meschieri, W. (2012).

Principi e strumenti della fotogrammetria Definizione

e classificazione. Zanichelli editore S.p.A., Bologna,

Italy.

Checa, D., Gatto, C., Cisternino, D., De Paolis, L. T.,

and Bustillo, A. (2020). A Framework for Educa-

tional and Training Immersive Virtual Reality Experi-

ences. In 7th International Conference on Augmented

and Virtual Reality and Computer Graphics (Salento

AVR 2020), September 7-10, 2020, Lecture Notes in

Computer Science, volume 12243, pages 220–228.

Springer.

Checa, D., Miguel-Alonso, I., and Bustillo, A. (2021).

Immersive virtual-reality computer-assembly serious

An Immersive Virtual Reality Application to Preserve the Historical Memory of Tangible and Intangible Heritage

285

game to enhance autonomous learning. Virtual Real-

ity.

Ciardo, G. (2014). Il Palazzo Baronale di Corsano: tra

storia e architettura. Tesi di Laurea. Department of

Cultural Heritage, University of Salento, Lecce, Italy.

Cronbach, L. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal

structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3):297–334.

De Paolis, L. T., Chiarello, S., D’Errico, G., Gatto, C.,

Nuzzo, B. L., and Sumerano, G. (2021). Mobile

Extended Reality for the Enhancement of an Under-

ground Oil Mill: A Preliminary Discussion. In 8th

International Conference Augmented and Virtual Re-

ality, and Computer Graphics (Salento AVR 2021),

September 7-10, 2021, Lecture Notes in Computer

Science (LNCS 12980), pages 326–335. Springer.

De Paolis, L. T. and De Luca, V. (2022). The effects

of touchless interaction on usability and sense of

presence in a virtual environment. Virtual Reality,

26(4):1551–1571.

De Paolis, L. T., Aloisio, G., Celentano, M. G., Oliva, L.,

and Vecchio, P. (2011a). Experiencing a town of the

Middle Ages: An application for the edutainment in

cultural heritage. In IEEE 3rd International Con-

ference on Communication Software and Networks,

pages 169–174.

De Paolis, L. T., Aloisio, G., Celentano, M. G., Oliva, L.,

and Vecchio, P. (2011b). MediaEvo project: A seri-

ous game for the edutainment. In 3rd International

Conference on Computer Research and Development,

volume 4, pages 524–529.

De Paolis, L. T. and De Luca, V. (2020). The impact

of the input interface in a virtual environment: the

Vive controller and the Myo armband. Virtual Reality,

24(3):483–502.

Gatto, C., D’Errico, G., Paladini, G., and De Paolis, L.

T. (2021). Virtual Reality in Italian Museums: A

Brief Discussion. In 8th International Conference on

Augmented and Virtual Reality and Computer Graph-

ics (Salento AVR 2021), September 7-10, 2021, Lec-

ture Notes in Computer Science, volume 12980, pages

306–314. Springer.

Germak, C., Di Salvo, A., and Abbate, L. (2021). Aug-

mented Reality Experience for Inaccessible Areas in

Museums. In Proceedings of EVA London 2021, pages

39–45.

Messemer, H. (2016). The beginnings of Digital Visualiza-

tion of Historical Architecture in the Academic Field.

Palatium e-Publications, Monaco.

Revelle, W. (1978). ICLUST: A cluster analytic ap-

proach to exploratory and confirmatory scale con-

struction. Behavior Research Methods & Instrumen-

tation, 10(5):739–742.

Revelle, W. (1979). Hierarchical cluster analysis and the in-

ternal structure of tests. Multivariate Behavioral Re-

search, 14(1):57–74.

Robin, B. (2006). The educational uses of digital story-

telling. In Crawford, C., Carlsen, R., McFerrin, K.,

Price, J., Weber, R., and Willis, D., editors, Proceed-

ings of SITE 2006 - Society for Information Tech-

nology & Teacher Education International Confer-

ence, pages 709–716. Orlando, Florida, USA: Associ-

ation for the Advancement of Computing in Education

(AACE).

Schubert, T., Friedmann, F., and Regenbrecht, H. (2001).

The experience of presence: Factor analytic insights.

Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments,

10(3):266–281.

Schwind, V., Knierim, P., Haas, N., and Henze, N. (2019).

Using Presence Questionnaires in Virtual Reality. As-

sociation for Computing Machinery.

Sànchez Mateos, D. (2018). El nuevos museos y los nuevos

públicos. El videojuego como un nuevo recurso de co-

municación, volume 3. Economia della Cultura.

UNESCO-ICH (2003). Text of the Convention for the Safe-

guarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. https:

//ich.unesco.org/en/convention.

Witmer, B. G., Jerome, C. J., and Singer, M. J. (2005). The

factor structure of the Presence Questionnaire.

Witmer, B. G. and Singer, M. J. (1998). Measuring pres-

ence in virtual environments: A presence question-

naire. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environ-

ments, 7(3):225–240.

HUCAPP 2023 - 7th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

286