Assessing Security and Privacy Insights for Smart Home Users

Samiah Alghamdi

a

and Steven Furnell

b

Cyber Security Research Group, School of Computer Science, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, U.K.

Keywords: Smart Home, Privacy, Security, Internet of Things, Usability.

Abstract: Recently, the number and range of Internet-connected devices have increased rapidly, especially due to

adoption of the Internet of Things and smart home contexts. As a result, users can find themselves needing to

be concerned with the security and privacy of an increasing range of devices. This paper explores the

challenges that users can face in understanding and using the related features on their devices. The first

element of the work is approached by assessing the user-facing materials (e.g., instruction manuals and online

guidance) for a wide variety of smart home devices to determine the extent to which security and privacy

aspects (and related features) are highlighted and explained. Having established that the situation is

inconsistent, the work proceeds to assess the user experience in practice, by examining how easily a series of

security and privacy-related tasks may be accomplished via three alternative smart speakers. The findings

highlight further inconsistency and suggest that users could face considerable challenges keeping track of

security settings and status of multiple devices across a smart home, and the need for information to be

presented in a more coherent form.

1 INTRODUCTION

Smart homes are based upon Internet-connected

versions of household devices that have traditionally

operated in a standalone manner. Satpathy (2006)

described a smart home as one "which is smart

enough to assist the inhabitants to live independently

and comfortably with the help of technology is

termed as a smart home. In the smart home, all the

mechanical and digital devices are interconnected to

form a network, which can communicate with each

other and the user to create an interactive space".

Smart home devices may share information

gathered by applications and can exist in widely

varying configurations. This, in turn, indicates that

devices can be connected to one or many devices.

While users are offered resulting flexibility and

convenience, the fact that the devices are online, as

well as collecting, storing, and communicating user

data, leads to associated considerations around

security and privacy.

The rapid growth and proliferation of smart home

devices has made it difficult for some users to keep

up with the pace of change. While they use the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3028-2910

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0984-7542

devices, they may not fully understand and manage

the resulting security and privacy options that may be

associated with them. With this in mind, this research

aims to investigate the user experience and determine

areas in which further support may be needed. The

main contributions of the resulting study are:

to investigate the extent to which security and

privacy issues are made apparent to users of

smart home devices.

to assess the nature of the user experience when

attempting to utilise smart home devices to

perform security- and privacy-related operations.

2 BACKGROUND

Today's common smart home includes smart TVs,

speakers, cameras, music streaming devices, smart

lighting, and smart thermostats. Moreover, many

smart home devices may be linked to a managing

system utilizing a house location network. Various

devices interact with the user's phone applications

and communicate with remotely hosted services

(Mazwa & Mazri, 2018). For instance, many security

592

Alghamdi, S. and Furnell, S.

Assessing Security and Privacy Insights for Smart Home Users.

DOI: 10.5220/0011741800003405

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2023), pages 592-599

ISBN: 978-989-758-624-8; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

cameras keep video storage on an external server that

users can access anywhere and anytime. Meanwhile,

smart assistants, such as Alexa, benefit from the use

of cloud-based benefits.

Many researchers use the Internet of Things

concept to classify security issues in smart homes into

four categories: application security, device security,

network security, and cloud-based security (Alrawi et

al., 2019). For clarification, smart home devices are

advanced IoT devices that can sense data and record

and transmit it to servers hosted on the cloud,

delivering the services to smart home users. For

instance, when a security camera detects motion, a

video will be saved and transferred to the cloud for

further analysis or storage. Additionally, most

devices provide smartphone apps that permit users to

interact with and configure them.

Information security means protecting data from

unauthorized access. Privacy concerns involve a

user's control over the creation and usage of their data

(Kotz et al., 2009). Consequently, privacy depends on

security, as the data must be genuinely secure before

privacy concerns arise. However, privacy is essential

for smart home applications, as there are many users

influencing the same information, and the connection

between them is required to clearly explain and

clarify the issues of data ownership. The domain of

suggested solutions for IoT privacy covers network,

design, and socio-technical efforts; Nevertheless,

Jacobsson & Davidsson (2015) recommend that it is

essential to understand users to be able to generate

usable privacy tools. This motivates us to assess the

availability of privacy and security information to

users if they search for it.

Previous HCI researchers have investigated the

mental models of users using smart home devices. For

example, Zheng (2017) conducted semi-structured

interviews with the users of smart homes were

performed to comprehend their privacy concerns and

mental models. They discovered that users of smart

homes sacrifice their privacy for their convenience.

However, Emami-Naeini et al., (2019) and Leo

Gorski et al. (2018) investigated smart home security

perceptions, determined characteristics that impact

security decisions, and studied users' concerns before

and after buying devices. Other researchers

investigated access-control procedures for smart

home devices (Colnago et al., 2020; He et al., 2018;

Zeng et al., 2019). For example, Zeng et al. (2019)

created a prototype and assessed the usability of an

access control application. Colnago et al. (2020)

analysed Personalised Privacy assistants in the IoT to

permit users to discover and manage data collection

with nearby smart devices. He et al., (2018) explored

how access control policies in smart home devices

vary based on contextual aspects such as device

abilities and user relationships.

Many user privacy experiments concerning IoT

technologies have been performed in temporary or

laboratory environments. One such experiment was

conducted on five users in one week with a custom

IoT device (Worthy et al., 2016). Moreover,

experiments conducted to understand user concerns

privacy with smartwatches (Udoh & Alkharashi,

2017) and toys connected to the internet (Mcreynolds

et al., 2013) have also explained user attitudes and

identified more functional designs for IoT privacy.

Related work had a few privacy concerns regarding

the data itself in nature; with apparent concerns about

how businesses would manage the data (Rodden et

al., 2013) Participants in this experiment were

principally interested in increasing advertising and

marketing their data for profit.

Based upon the resulting appreciation of the

problem, it is considered that users would benefit from

a more effective exposition of security and privacy

issues, as well as a harmonised means of understanding

the related status of their smart home and associated

devices within it. These issues are consequently

explored in more detail in the following sections.

3 EVALUATING PROVISION OF

INFORMATION

Although services provided by smart home devices

improve our quality of life, they invariably increase

concerns regarding the privacy of personal

information. It is therefore relevant to consider the

extent to which security and privacy issues are

highlighted to users, and the extent to which they

must search to find relevant information. With this in

mind, we evaluated what users could find out about

the devices from online sources and the extent to

which users are presented with this information as

part of the standard guidance. The evaluation

considered six types of smart home devices: TVs,

Speakers, Thermostats, Robotic Vacuum, Smart

Video Doorbells and Displays. We then evaluated an

average of three companies for each type.

Furthermore, we selected companies with large,

medium, and small market shares in smart homes. In

each case we examined whether security/privacy

aspects were mentioned in the manufacturer’s

product web page, the user manual, an online FAQ

page (or similar) or other online sources. The latter

would include the privacy policies of smart home

Assessing Security and Privacy Insights for Smart Home Users

593

devices. Multiple companies take the form of long

privacy policies, which usually include legal jargon

and are difficult for users to read (Fabian et al., 2017),

making it cumbersome, if not inconceivable, for them

to use and control their data effectively.

The sub-sections that follow present a summary

of the findings for each category of smart device.

3.1 Smart Speakers

Smart speakers enable users to control and interact

with the device via voice commands, using a

virtual/voice assistant (Alexa, Google, Siri) to

perform tasks and access online services.

This assessment evaluates Google Nest, Amazon

Echo Dot, and Apple HomePod. Most devices and

their applications have the potential to invade the

user's privacy by collecting personal data, addresses,

voice recordings, and the geolocation of the user's

smartphone. Moreover, most smart speakers share

voice recordings with third parties for purposes such

as marketing and improving functionally (the

HomePod, did not share data with third parties).

Regarding privacy-related information presented

in the user manual page, we found that Google Nest

speakers indicated how to turn off the microphone.

The HomePod presented more information about user

privacy than other smart speakers. It will be difficult

for the users to read and understand privacy policy

pages because they were over long and complicated.

3.2 Smart Thermostat

Smart thermostats are a recent technology that

connects the heating system in a home to the Internet,

allowing the user to change the temperature or turn

off the heating from anywhere using the application.

This review examined the Netatmo smart ther-

mostat and the Amazon smart thermostat. Most smart

thermostat and their applications have the potential to

invade the user's privacy. All smart thermostats collect

personal information. Furthermore, Netatmo can

collect the house location, whereas Amazon collects

voice recordings because the user will require the

speaker to control the device via voice activation.

We found that all devices do not present privacy-

related information on the user manual page. Again,

the privacy policy pages are too long and complicated

for users to read and understand.

3.3 Robotic Vacuum

A robotic vacuum is a self-propelled floor cleaner. It

works using Lidar lasers or room-mapping sensors on

the vacuum to scan and map the house without human

intervention. Moreover, some vacuums are provided

with a built-in camera

This assessment examined devices from four

companies: Eufy, Ecovacs Deebot, Wyze, and

iRobot. All collected personal data and tracked the

location using the applications, and all share users'

information with third parties. Furthermore, all the

applications have the potential to invade the user's

privacy by tracking the location because they work

using Lidar lasers or room-mapping sensors on the

vacuum to scan and map the house.

The devices did not include privacy-related

information in user manual pages. Their separate

privacy policy pages were complex.

3.4 Smart Video Doorbells

Smart Video Doorbell is an internet-connected smart

device that combines a doorbell, microphone, and

camera into a single device. As a result, users can

video record who is at the door. Smart doorbells are

linked to the WIFI, and a smartphone application

permits live viewing for users.

This assessment examined Netatmo, Eufy and

Ring. Providers usually collect personal data, house

location, video recording, and face images. Further,

most devices and applications can invade the user's

privacy via cameras, microphones, and track location.

Moreover, Eufy and Ring share data with third

parties, while Netatmo applies the strictest

regulations to data collection.

Regarding privacy-related information on the

user manual page, we found that all devices do not

present any information.

3.5 Smart Displays

Smart display usually works as the hub in the smart

home and permits the user to watch YouTube, view

their photos, listen to podcasts, and maintain domestic

lighting control with their voice.

This assessment investigated Google Nest Hub,

Amazon Echo Show, and Facebook Portal. All collect

personal data, voice recording for the users and the

geolocation of the user's smartphone. Additionally,

Facebook Portal collects social contact because it

requires signing in with a WhatsApp or Facebook

account. Moreover, most smart displays share data

with third parties, including advertisers, analytics

services, and measurement partners. Besides, all

devices and their applications have the potential to

invade user privacy.

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

594

Regarding how much privacy-related information

is presented on the user manual page, we found that

just the Facebook Portal mentioned how to turn off

the camera and the microphone.

3.6 Smart TVs

A smart TV is a television connected to the internet

with computational abilities. These upgrades to the

standard TV group allow the smart TV to operate

interactive applications and stream content from the

Internet.

This review investigated the Sony and Samsung

Smart TV. All collect personal data, and social

contact, and may share data with third parties.

Furthermore, it may share geolocation, personal

information and browsing history.

Regarding privacy-related information presented

on the user manual page, we found that Samsung

mentioned how to agree to use the privacy policy

without any further explanation. In contrast, Sony

does not present any related information.

3.7 Summary

Table 1 summarises the overall findings, denoting

whether security/privacy-related information was

Table 1: Security/privacy information at different stages.

Product

w

eb page

User

manual

FAQ

page

Other

Speaker

Echo Dot

HomePod

Nest

-

Thermostat

Amazon

-

Netatmo

Robotic Vacuum

Eufy

Ecovacs

Wyze

iRobot

Video Doorbell

Netatmo

Eufy

-

Ring

Display

Nest Hub

-

Echo Show

Portal

Smart TV

Sony

Samsung

-

identified at each stage (a dash indicates that the

element was not found). The ‘Other’ column refers to

sources such as privacy policies and notices.

4 EVALUATING FEATURE

ACCESSIBILITY

Having assessed the availability of information, the

next question was how easily a user can control

security and privacy features. Smart speakers were

selected for further examination as the most

widespread smart home device. Specifically, the

Amazon Echo, Google Nest, and Apple HomePod

devices (Figure 1) were chosen, reflecting three

popular options that typical users may own and use.

(a) (b) (c)

Figure 1: Smart Speakers selected for evaluation (a)

Amazon Echo (b) Google Nest and (c) Apple HomePod.

To explore how easily and consistently users can

locate and use relevant features, the study selected a

series of security- and privacy-relevant activities that

smart speaker users may wish to perform.

Listening and Recording: Smart speakers listen

and record user conversations to send data to

developers to enhance functionality.

Consequently, users may wish to mute the

microphone or delete these recordings.

- Microphone muting - The microphone

remains on to listen for the trigger words that

permit users to utilize the device. This

indicates that smart speakers are consistently

listening, raising privacy concern for some

users. Some devices (e.g., Google Nest and

Amazon Echo) have a physical switch to

mute or unmute their microphones.

- Deleting recordings - Captured recordings

can be deleted manually by users. Moreover,

Amazon and Google speakers enable

scheduled deletion of recordings regularly.

Audio Purchases: The smart speaker allows

users to add items to a shopping basket and

complete purchases via voice controls. As such,

smart speakers are linked to the user's payment

card and require protection to avoid unauthorised

purchases. Related protection features are:

Assessing Security and Privacy Insights for Smart Home Users

595

- Turning off audio purchase – The ultimate

protection is to disable the feature.

- Payment authorisation - Amazon Alexa

allows the user to establish a 4-digit voice

code to prevent unexpected orders or verify

purchases.

Turning off Location Services: Siri utilizes the

location of the Apple HomePod speaker to

provide regional news such as weather traffic and

nearby businesses. Moreover, location services

settings will apply to all Apple HomePods

speakers in the house. Therefore, the user should

be careful with this service because it indicates

home location, which may violate the user's

security and privacy. However, this feature is

only available via Apple HomePod.

Updating Smart Speaker Software: Updates

are released regularly to improve the device's

stability, adding new features, and closing

security gaps. Therefore, the user needs to review

the software version of the smart speaker device

and compare it to the latest version. It must be

updated if a smart speaker device runs an

outdated version.

Setting Up Voice Recognition: When a smart

speaker shares with different people, it can

convey details that are not specific to the user, or

it may share the user information with somebody

else. Therefore, this can lead to weak

authorization security issue. In cases like this, the

voice match feature will allow the smart speaker

to fetch the data specific to the user only if it

hears the user's voice.

Space constraints prevent us from discussing the

details in all cases, and so the steps involved in

deleting voice recording data are presented as a

specific example. A summary of the steps involved

across the other tasks are presented in Table 2.

Apple HomePod: The user can delete recordings

from the Home application by following the

steps in Figure 2.

While it requires fewer steps

than the others, steps at the second and third

stages are not necessarily intuitive.

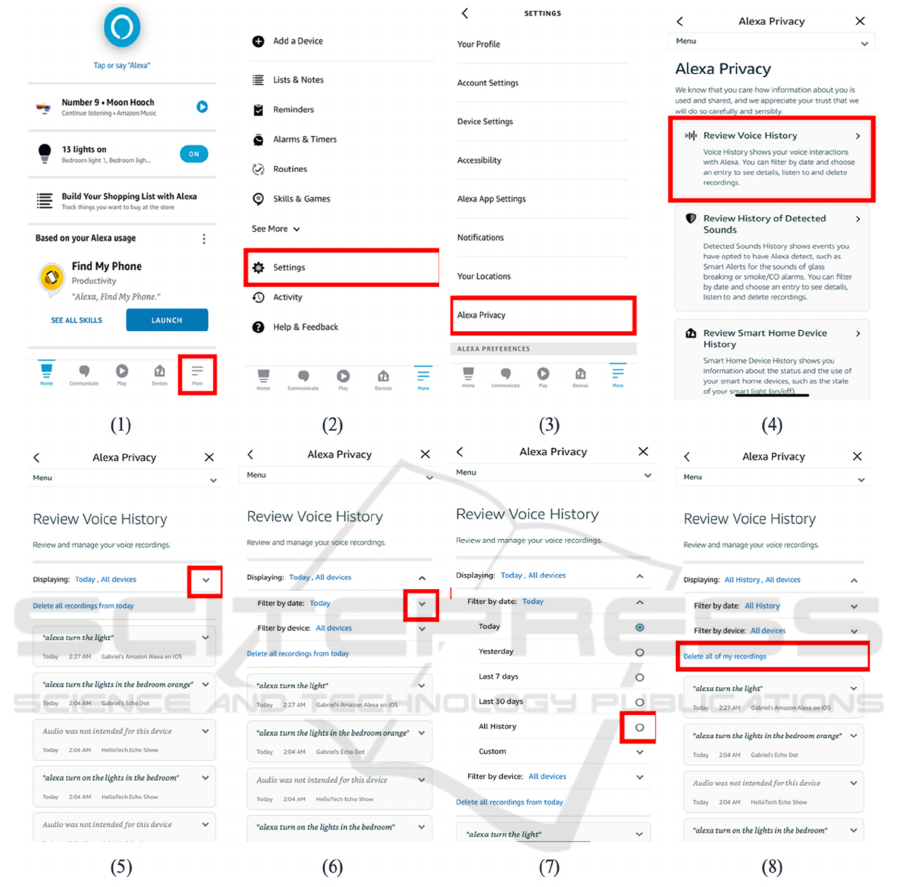

Amazon Echo Dot: The user can delete

recordings manually via the Alexa application

settings, as shown in Figure 3. To delete all

recordings, they must perform at least eight

steps. Moreover, they may need help due to

ambiguous options. For example, when opening

Settings (Step 3), how will they know to choose

Alexa Privacy rather than Account Setting?

Therefore, the users may waste time trying to

find the correct route, which can be cumbersome.

Google Nest: The user can delete all records

from their Google account by following several

steps, as shown in Figure 4. It indicates that they

must select various options and scroll down via

pages to find the Voice & Audio Activity page

to delete all voice records. These steps are not

obvious due to the variety and unclear choices

and scrolling down via pages, which can make

the user try several options and undo them to

reach the chosen option. For example, if the user

opens the setting page, how will they know to

select Google Assistant and not Voice?

Figure 2: Steps required to Delete Siri History from HomePod via the Home app.

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

596

Figure 3: Steps required to Delete all the Recording from Amazon Smart Speaker.

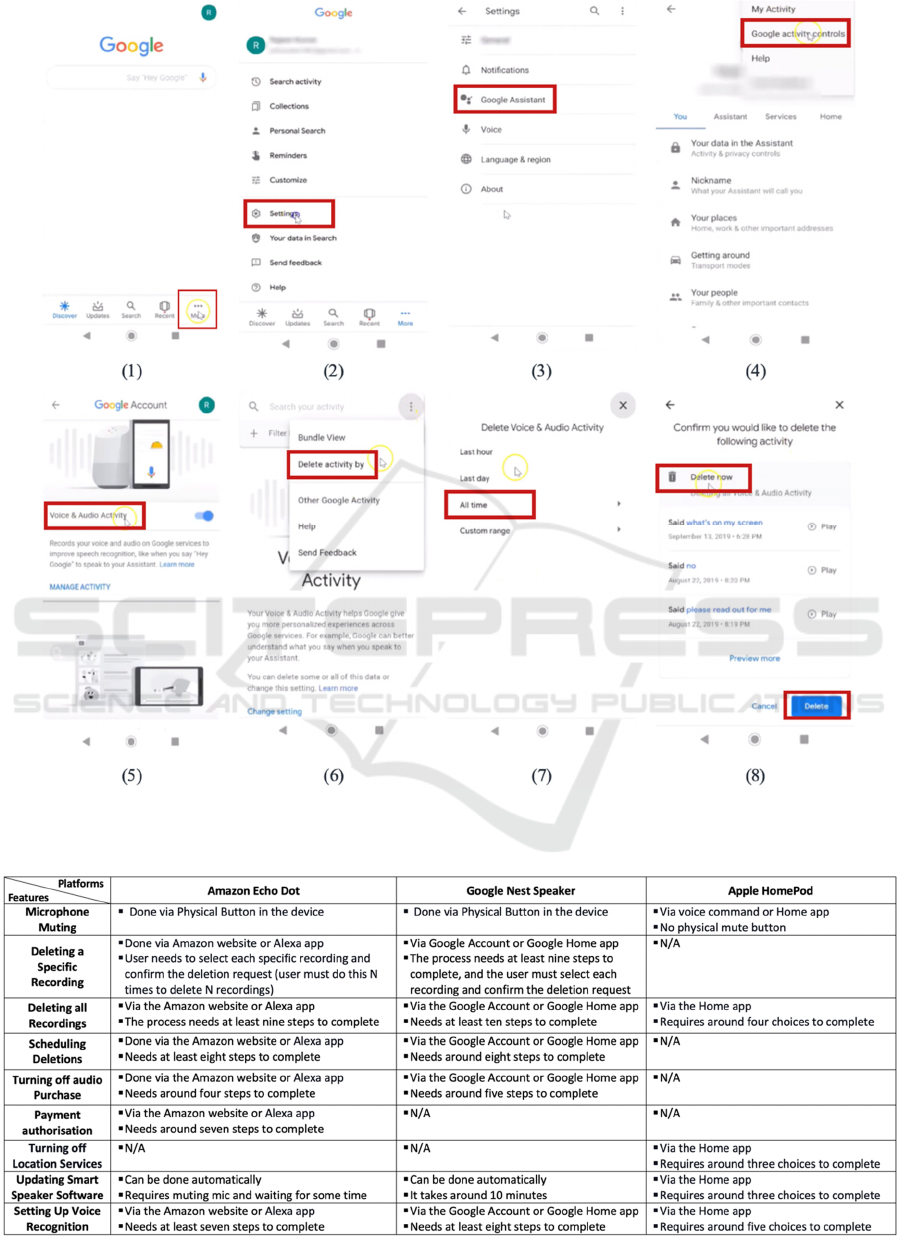

Table 2 summarises the overall findings and the

steps that a user needs to perform for each feature.

This highlights the difference in executing the same

feature between the three platforms.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The findings indicate that smart home devices make

it difficult for end-users to deal with security and

privacy issues in a consistent manner. In addition to

finding varying levels of information available to

guide them at the outset, users are then faced with

individual devices that perform similar functions in

varying ways, thereby complicating (and potentially

frustrating) the task of managing security and privacy

across a growing range of devices within their smart

home. This suggests a need to improve user

experience through better attention to HCI aspects.

Our resulting aim is to design and evaluate a

‘dashboard’ that consolidates status information from

multiple devices and presents it in a harmonised

manner, thereby giving the user a more readily

appreciable view of the status of their devices and the

smart home overall.

Assessing Security and Privacy Insights for Smart Home Users

597

Figure 4: Steps required to Delete all Records in Google Nest Speaker.

Table 2: Comparison of Smart Speakers Features on the selected platforms.

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

598

REFERENCES

Alrawi, O., Lever, C., Antonakakis, M., & Monrose, F.

(2019). SoK: Security Evaluation of Home-Based IoT

Deployments. Proceedings - IEEE Symposium on

Security and Privacy, 2019-May, 1362–1380.

https://doi.org/10.1109/SP.2019.00013

Colnago, J., Feng, Y., Palanivel, T., Pearman, S., Ung, M.,

Acquisti, A., Cranor, L. F., & Sadeh, N. (2020).

Informing the Design of a Personalized Privacy

Assistant for the Internet of Things. Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376389

Emami-Naeini, P., Dixon, H., Agarwal, Y., & Cranor, L. F.

(2019). Exploring How Privacy and Security Factor

into IoT Device Purchase Behavior. Proceedings of the

2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems, 12(2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605

Fabian, B., Ermakova, T., & Lentz, T. (2017). Large-scale

readability analysis of privacy policies. Proceedings -

2017 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on

Web Intelligence, WI 2017, 18–25. https://doi.org/

10.1145/3106426.3106427

He, W., Golla, M., Padhi, R., Ofek, J., Dürmuth, M.,

Fernandes, E., & Ur, B. (2018). Rethinking Access

Control and Authentication for the Home Internet of

Things (IoT). In Proceedings of the 27th USENIX

Security Symposium. https://www.usenix.org/

conference/usenixsecurity18/presentation/he

Jacobsson, A., & Davidsson, P. (2015). Towards a model

of privacy and security for smart homes. IEEE World

Forum on Internet of Things, WF-IoT 2015 -

Proceedings, 727–732. https://doi.org/10.1109/WF-

IOT.2015.7389144

Kotz, D., Avancha, S., & Baxi, A. (2009). A privacy

framework for mobile health and home-care systems.

Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and

Communications Security, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.11

45/1655084.1655086

Laricchia, F. (2022). Smart speakers - Statistics & Facts |

Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/4748/smart-

speakers/

Leo Gorski, P., lo Iacono, L., Wermke, D., Stransky, C.,

Moeller, S., Acar, Y., & Fahl, S. (2018). Informal

Support Networks: an investigation into Home Data

Security Practices. www.usenix.org/conference/

soups2018/presentation/gorski

Madakam, S., & Ramaswamy, R. (2014). Smart homes

(conceptual views). 2nd International Symposium on

Computational and Business Intelligence. IEEE., 63–

66. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/711

9535/

Mazwa, K., & Mazri, T. (2018). A Survey on the security

of smart homes: Issues and solutions. ACM

International Conference Proceeding Series, 81–87.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3289100.3289114

Mcreynolds, E., Hubbard, S., Lau, T., Saraf, A., Cakmak,

M., & Roesner, F. (n.d.). Toys that Listen: A Study of

Parents, Children, and Internet-Connected Toys.

Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.11

45/3025453

Rodden, T. A., Fischer, J. E., Pantidi, N., Bachour, K., &

Moran, S. (2013). At home with agents: Exploring

attitudes towards future smart energy infrastructures.

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems -

Proceedings, 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1145/2470

654.2466152

Satpathy, L. (2006). Smart Housing: Technology to Aid

Aging in Place - New Opportunities and Challenges.

Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarsjunction.ms

state.edu/td/3967

Udoh, E. S., & Alkharashi, A. (2017). Privacy risk

awareness and the behavior of smartwatch users: A case

study of Indiana University students. FTC 2016 -

Proceedings of Future Technologies Conference, 926–

931. https://doi.org/10.1109/FTC.2016.7821714

Worthy, P., Matthews, B., & Viller, S. (2016). Trust me:

Doubts and concerns living with the internet of things.

DIS 2016 - Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference

on Designing Interactive Systems: Fuse, 427–434.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2901790.2901890

Zeng, E., Roesner, F., & Allen, P. G. (2019).

Understanding and Improving Security and Privacy in

{Multi-User} Smart Homes: A Design Exploration and

{In-Home} User Study. https://www.usenix.org/

conference/usenixsecurity19/presentation/zeng

Zhang, B., Zou, Z., & Liu, M. (2011). Evaluation on

security system of internet of things based on Fuzzy-

AHP method. 2011 International Conference on E-

Business and E-Government, ICEE2011 - Proceedings,

2230–2234. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEBEG.2011.588

1939

Zheng, S. (2017). User Perceptions of Privacy in Smart

Homes. https://dataspace.princeton.edu/handle/88435/

dsp01kd17cw477

Assessing Security and Privacy Insights for Smart Home Users

599