Technical Realization and First Insights of the Multicenter

Integrative Breast Cancer Registry INTREST

Thomas Ostermann

1

, Sebastian Unger

1

, Michaela Warzecha

2

, Sebastian Appelbaum

1

,

Daniela Rodrigues Recchia

1

, Holger Cramer

3

and Heidemarie Haller

4

1

Department for Psychology and Psychotherapy, Witten/Herdecke University, Alfred Herrhausen-Straße 50,

58448 Witten, Germany

2

Medical Informatics, University of Applied Sciences Dortmund, Emil-Figge-Str. 42 44227 Dortmund, Germany

3

Institute for General Practice and Interprofessional Care, University Hospital Tuebingen and Bosch Health Campus,

Stuttgart, Auerbachstraße 110, 70376 Stuttgart, Germany

4

Department of Internal and Integrative Medicine, Evang. Kliniken Essen-Mitte, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Duisburg-Essen, Am Deimelsberg 34a,45276 Essen, Germany

Holger.Cramer@med.uni-tuebingen.de, Heidemarie.Haller@uk-essen.de

Keywords: Clinical Registry, Breast Cancer, Database, Baseline Characteristics.

Abstract: Cancer is one of leading causes of mortality worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN database, 19.3 million

new cancer cases and 10 million cancer deaths worldwide were counted in 2020. Thus, there is an absolute

necessity for statistical data on cancer incidence and treatments. This is mainly done by cancer registries,

which aim at collecting, managing, and analyzing health and demographic data on individuals diagnosed with

cancer. As more and more patients make use of integrative oncology to optimize their health and quality of

life during and after cancer treatment, it is important to gather clinical registry data of complementary as well

as conventional cancer care. The INTREST registry is the first approach that aims to identify predictors of

treatment-response in women undergoing individualized, integrative breast cancer treatment. This article

reports on the technical realization and representativity of the registry based on 3,341 eligible women and 885

cases included in interim statistical analysis. The analyses show that the INTREST sample of women suffering

from breast cancer does not significantly differ from population-based registries and pragmatic trial data of

breast cancer patients in Germany with respect to main sociodemographic and clinical cancer data. However,

completeness, particularly in tumor classification, currently is a major limitation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cancer is still one of the leading causes of mortality

worldwide. According to the GLOBOCAN database,

19.3 million new cancer cases and 10 million cancer

deaths worldwide were counted in 2020 (Sung et al.,

2021; Ferley et al., 2021). Thus, there is an absolute

necessity for statistical data on cancer incidence and

treatments. This is mainly done by cancer registries,

which aim at collecting, managing, and analyzing

health and demographic data on persons diagnosed

with cancer (Jensen et al., 1991). Cancer registries

can be classified into three general types:

1. Hospital based registries, which maintain data on

all patients diagnosed and/or treated for cancer at

their facility and report cancer cases to the central

or state cancer registry as required by law.

2. Population-based central registries, which collect

data on all cancer patients within certain geogra-

phical areas.

3. Special purpose registries, providing data on a

particular type of cancer and/or treatment.

The INTREST cancer registry belongs to the third

class of registries and collects data of women diag-

nosed with breast cancer with a special focus on inte-

grative oncological treatment approaches. Integrative

Oncology has its origins in the United States and per

definition combines conventional cancer care with

evidenced-based complementary therapies (CM).

The main goal of Integrative Oncology is to reduce

side effects of oncological treatments and to improve

patient's quality of life with a first medical guideline

being published in 2007.

Common symptoms, accompanying with the

diagnosis and treatment of cancer, include fatigue,

298

Ostermann, T., Unger, S., Warzecha, M., Appelbaum, S., Recchia, D., Cramer, H. and Haller, H.

Technical Realization and First Insights of the Multicenter Integrative Breast Cancer Registry INTREST.

DOI: 10.5220/0011667800003414

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2023) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 298-306

ISBN: 978-989-758-631-6; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

sleep disturbances, pain, neuropathy, and affective

disorders (Cheng et al., 2013; Patrick et al., 2004;

Singer et al., 2021). In order to improve quality of life,

women with breast cancer frequently use CM

(Molassiotis et al., 2005; Boon et al., 2007). How-

ever, patients often do not mention the use of CM to

their physicians unless they are explicitly asked about

it (Koenig et al., 2015; Samuels et al., 2017). This

lack of communication can lead to undesired

interactions between conventional and CM therapies

that, at worst, negatively impacts quality and quantity

of life (Alsanad et al., 2014; Ben-Arye., 2015; Bode

& Dong, 2015; Zeller et al., 2013).

Asking patients and systematically exploring

their concurrent CM use is recommended by inter-

national clinical practice guidelines (Greenlee et al.,

2014; Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie, 2017; Lyman

et al., 2018) but implemented only gradually by

physicians (Paepke et al., 2020; Grimm et al., 2021)

and initial registries (Schad et al., 2013; Dusek et al.,

2016).

Standard clinical cancer registries, in contrast,

usually do not assess data beyond tumor characteris-

tics, conventional treatment algorithms, and patient

survival while other supportive treatments, streng-

thening the physical and psychosocial resilience of

cancer survivors, are not yet included.

This article reports on the technical realization

and first results of the data analysis of the INTREST

registry, which aims at assessing data on the influence

of conventional and CM treatments as well as

physical and psychosocial resilience using qualitative

and quantitative endpoints.

2 MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 Guidelines, Ethics and Partners

The INTREST registry uses an epidemiological,

multi-center cohort design according to the Trans-

parent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model

for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) and

the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational

studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement

(Collins et al., 2015). The INTREST protocol is

approved by the respective ethics committees, regis-

tered at the World Health Organization (WHO) Inter-

national Clinical Trials Registry Platform / German

Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00014852), and pub-

lished in 2021 (Haller et al., 2021).

2.2 Technical Realization

In the initial phase, INTREST was developed for

local use. The basis was a Windows 10 machine with

the XAMPP package installed, an Apache distribu-

tion with a MySQL-Database and the scripting

language PHP (PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor) using

an architecture used in the medical learning context

(Ostermann et al.,

2018).

To make INTREST acces-

sible online, it was migrated to a server that was

already fully set up with a similar operating system

and software to those of the local machine, where

INTREST was previously running. Thus, design and

structure, which are briefly presented below, could be

retained during the migration without any

complications.

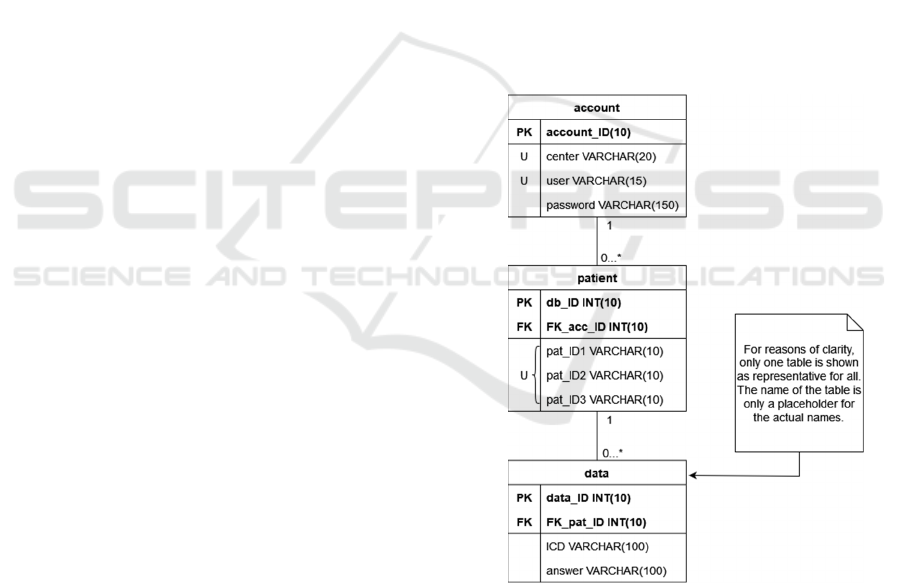

2.3 Data Model

All data are stored within a MySQL-Database. The

structure of the relational model is provided in

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Relational model of the data.

The structure of a table mostly follows the same

principle: The first column contains the primary key,

which consists of an integer value and is automa-

tically incremented when a new entry is created. This

is followed by the foreign key column, which is not

required only for the account table. Finally, there are

two columns for an alphanumeric input in the form of

a limited number of characters in the regular tables,

Technical Realization and First Insights of the Multicenter Integrative Breast Cancer Registry INTREST

299

while there are three such columns in the tables for

accounts and patients. In general, these columns

represent a survey item and the corresponding res-

ponse. The patient table uses these columns for

different types of IDs (identifiers), which are unique

in their three-way combination and consist of a

sequential center number, an individual five-digit

patient code, and a patient identification number of

the specific clinic. In the account table, on the other

hand, these columns are related to username,

password, and name of the study center. Another

characteristic of the account table is that two of its

columns are unique, since each study center receives

only one account with one user.

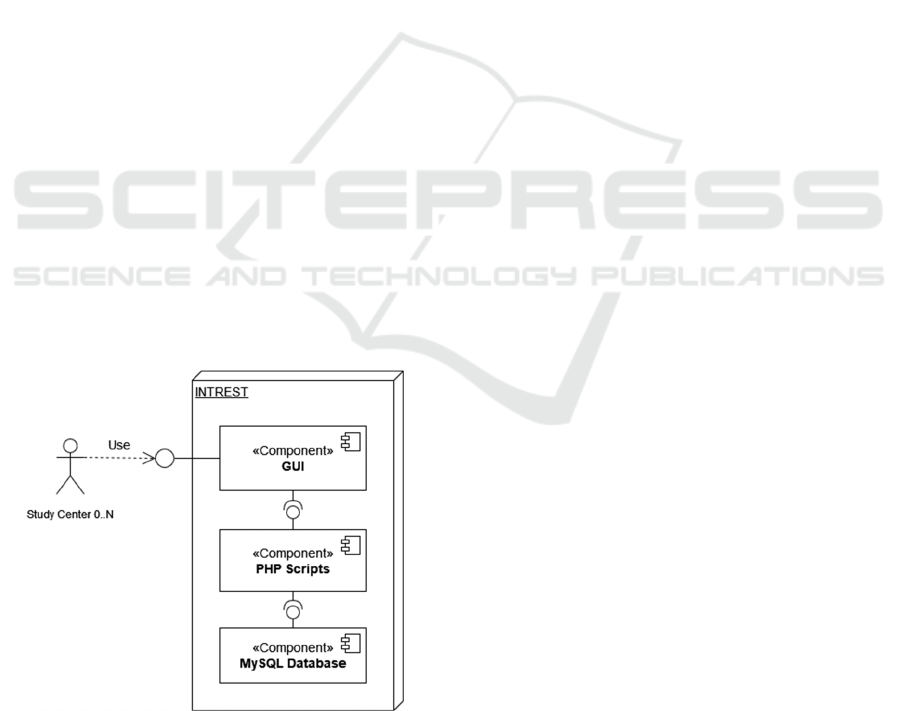

2.4 System Architecture

INTREST’s architecture can be summarized in three

main components (see Figure 2) that follow the

principle of a layer concept for smaller application

(Richards, 2015). On top, there is a GUI (Graphical

User Interface) that allows the communication

between client and server through internet. With this

study nurses of a center can access INTREST at any

time to create new patients or add their individual

Case Report Forms (CRFs). Each page of the GUI

uses a different script because a page refers to a

specific point in time when various items are

recorded. After the CRF inputs are transmitted to a

script, they are transformed to MySQL queries and

redirected to the database at the bottom of

INTREST’s architecture. If a page is accessed with

data already entered, a message appears stating that

the data already exists and can no longer be entered.

Figure 2: Component model of INTREST, visualizing the

interactions between the main components and the study

centres.

2.5 Data Security and Validity

In any application that is connected to the Internet and

contain data, especially if it is medical or personal

data as with INTREST, certain security precautions

are necessary. Hoque et al. (2014) describe many

diverse network attacks and that these attacks often

target web sites or databases to gather information.

Therefore, approaches should be applied to reduce the

risk of exposing data in network applications, which

might have security issues or process medical data.

HTTPS (Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure) is one

of the worldwide used approaches to encrypt the

communication between clients and servers. The

server, hosting INTREST, supports this protocol in

conjunction with an officially authorized certificate,

allowing secure data retrieval and transmission.

Since the data is transferred from collected

medical records in paper form, special attention is put

on this issue. Only medical personnel who have been

trained by the respective study center are authorized

for this. Their tasks are the formal monitoring for

completeness and the input of the paper CRFs into the

specially developed GUI. Therefore, they are suppor-

ted on the software side.

First, entered data is validated, using programmed

validation checks, e.g., checks for required values,

item types, and item ranges. And second, if a response

of an item is not recognizable, this item is stored in

the database with a discrepancy note. In regular data

review meetings, all such discrepancies are discussed

and clarified by comparing the entries in the database

with the source data.

Another aspect of data security concerns the

storage of data. Since it should not be possible to draw

conclusions about an individual participant, the data

are exclusively pseudonymized during transmission

to the registry. This even applies to the statistical

analysis, where pseudonymized data is transferred to

a CSV (Comma-Separated Values) file. At this stage,

the data is only checked for accuracy and comple-

teness by randomly comparing a set of items with the

original database.

2.6 Patients and Outcomes

Female patients diagnosed with primary breast cancer

stage I-III according to the pTNM (pathological

Tumor-Node-Metastasis) classification,

who received

individualized integrative cancer treatments in one of

the participating study centers, were included in the

registry. Cancer diagnosis and treatment data as well as

those on progression were retrieved from medical

records, while women were asked to complete

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

300

sociodemographic data and the following Patient

Reported Outcomes (PROs);

• Cancer-related quality of life and fatigue,

assessed by the Functional Assessment of

Cancer Therapy General (FACT-G) (Brucker et

al., 2005) and the associated Fatigue Scale

(FACIT-F) (Yost & Eton, 2005),

• Distress assessed by the Questionnaire on

Distress in Cancer Patients (QSC) (Book et al.,

2011),

• Depression assessed by the Center for Epide-

miologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD)

(Stafford et al., 2014),

• Hopelessness assessed by the Brief Hopeless-

ness measure (BH) (Fraser et al., 2014),

• State anxiety assessed by the Patient-Reported

Outcomes Measurement Information System

Emotional Distress Anxiety Form (PROMIS-

EDA) (Schalet et al., 2016) and progression

anxiety assessed by the Fear of Relapse/Recur-

rence Scale (FRRS) (Thewes et al., 2012),

• Emotion regulation assessed by the Emotion

Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) (Gross et al.,

2003),

• Sleep disturbance assessed by the Patient-

Reported Outcomes Measurement Information

System Sleep Disturbance Form (PROMIS-SD)

(Yu et al., 2011),

• Spiritual well-being assessed by the Functional

Assessment of Chronic Illness Spiritual Well-

Being Scale (FACIT-SP) (Bredle et al., 2011),

• Social support assessed by the perceived

Available Support subscale of the Berlin Social

Support Scales (BSSS) (Schulz et al., 2003),

• Physical activity assessed by International

Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) (Craig

et al., 2003),

• Healthy diet assessed by the Mediterranean Diet

Adherence Screener (MEDAS) (Schroder et al.,

2011),

• CM attitutes assessed by the CAM Health Belief

Questionnaire (CHBQ) (Lie et al., 2004),

• Interest in CM assessed by a numeric rating

scales (NRS),

• Use of CM assessed by an extended version of

the International Complementary and Alterna-

tive Medicine Questionnaire (I-CAM-Q) (Quant

et al., 2009),

• Adverse events assessed by the Memorial

Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) (Chang et

al., 2000) and

• Therapy satisfaction assessed by the Client

Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) (Attkisson et

al., 1982).

2.7 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis included univariate analyses of

frequencies using Chi-Square statistics and analyses

of mean differences using a t-test with respect to

group differences. For all analyses, due to the high

sample size, a p-value of .01 was considered to be

significant.

3 RESULTS

Originally developed at the Department of Internal

and Integrative Medicine, KEM, University of

Duisburg-Essen and the KEM Breast Unit (Start in

September 2017), three additional German cancer

centers have joint into the INTREST-registry: the

Department of Gynecology at the Robert-Bosch-

Hospital (Stuttgart in January 2018), the Breast Unit

of the St. Franziskus-Hospital (Münster in September

2019), and the Breast Unit of Hall (Hall in November

2020).

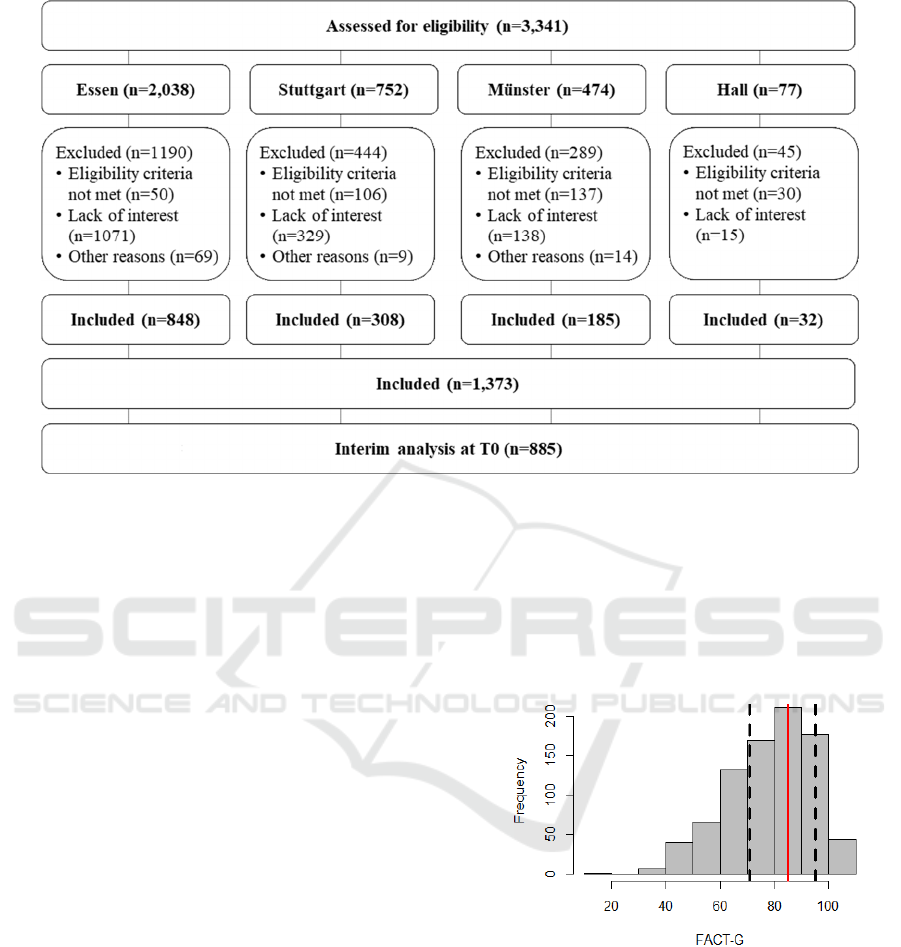

The recruitment in the four study centers of the

INTREST project amounts to N = 1373 patients with

TNM I-III breast cancer of which N = 885 were

eligible for the present interim analysis at baseline.

For the individual study centers, patient recruit-

ment results are presented in Figure 3.

3.1 Sociodemographic Data

The mean age at baseline is 57.0 ± 11.6 years, with

the vast majority born in Germany (92 %). 62 % of

the patients are married and live with their spouse.

The average weight and height are 72.2 ± 16.2 kg

(kilogram) and 167.3 ± 6.3 cm (centimeters), corres-

ponding to a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 25.8 ± 5.5.

More than half of the sample (61.2 %) is employed.

In addition, almost half of the sample had a high

school (18.1 %) or university degree (30.0 %).

3.2 Cancer Parameters

Table 1 provides cancer related baseline values com-

pared to similar cohort studies and representative

population data from a German/Saarland cancer

registry.

With respect to the age at first cancer diagnosis,

the INTREST data are significantly lower compared

to population data of the Saarland cancer registry (p

Technical Realization and First Insights of the Multicenter Integrative Breast Cancer Registry INTREST

301

Figure 3: Patient flow chart of the INTREST registry.

< 0.001; Jansen et al., 2020), which, however,

includes not only breast cancer but mixed cancer

diagnoses. Tumor type shows similar percentages

compared with the Saarland registry (p = 0.017),

while the distribution of tumor receptor subtypes is

not comparable to the TMK cohort (p < 0.001)

(Marschner et al., 2019). However, it has to be noted

that the TMK cohort is significantly younger than the

INTERST sample (p < 0.001), as only women with

early breast cancer were included.

Tumor staging is comparable between INREST

and the CM trial (p = 0.11; Witt et al., 2015), while

INTREST shows significantly different percentages

compared to the Saarland registry and the TMK

cohort (p < 0.001, respectively). Tumor grading

significantly differ between the samples (p < 0.001,

respectively) except the amount of G2 grading.

Status of menopause in the INTREST registry

does not significantly differ from the TMK cohort (p

= 0.14) and the pragmatic CM trial (p = 0.15).

3.3 Quality of Life

Quality of life measured with the FACT-G and

FACIT-F showed comparable values with respect to

other studies.

Figure 4 displays the FACT-G total score distri-

bution together with the median and interquartile

range (IQR) of the female cancer norm (Brucker et

al., 2005).

With a mean value of 78.8 ± 15.7 and a median of

80.7 (IQR: [68.2; 91.0]) the FACT-G shows an

expected distribution. This value is underpinned

when comparing it to other, e.g., with the mean value

of 76.2 of the trial of Witt et al. (2015) or with the

mean of 75.7 ± 15.7 of the TMK cohort (Marschner

et al., 2019), both presented in Table 1.

Figure 4: FACT-G distribution of the sample with median

(red line) and 1

st

and 3

rd

Quartile (dashed lines).

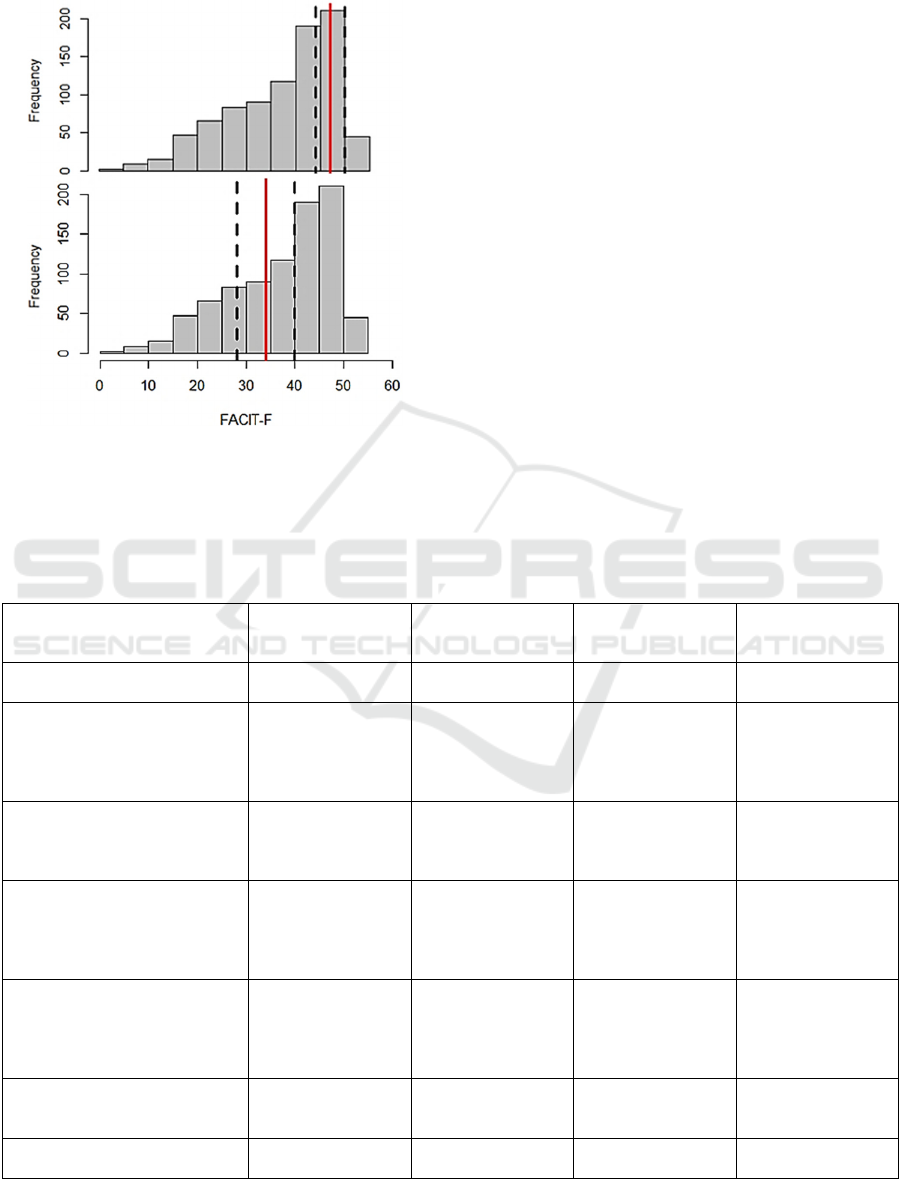

Figure 5 displays the FACIT-F total score distri-

bution. In contrast to figure 4, there are no quartile

norm values for breast cancer. Thus, comparative

values were taken from a sample of non-fatigued and

fatigued breast cancer patients at baseline from

(Courtier et al., 2013).

With a mean value of 37.8 ± 10.5 and a median of

41.0 (IQR: [30.0; 46.0]) the FACIT-F shows a distri-

bution between non-fatigued and fatigued patients (M

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

302

± SD: 36.4 ± 11.1; see Table 1) similar to the trial of

Witt et al. (2015).

Figure 5: FACIT-F distribution of the sample with median

(red line) and 1

st

and 3

rd

Quartile (dashed lines).

3.4 Interest in and Prior Use of CM

Finally, the interest in integrative cancer treatment

was remarkably high. On an NRS from 0 = no interest

to 10 = high interest, patients rated 7.7 ± 3.0.

However, their decision to be treated in an inte-

grative hospital was not driven by their interest: 73.4

% reported that integrative medicine was not relevant

for choosing the respective clinical center. 12.5 %

reported a slight moderating effect and only 14.0 %

based their decision for the hospital on the offer of

integrative therapies.

This is somehow in accordance with the fact that

only half of the patients (51.1 %) previously did not

use integrative therapies.

4 DISCUSSION

This paper presents the technical realization and first

results on representativity of the INTREST data, a

cancer registry for breast cancer patients treated with

integrative oncology.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics and medical history. Abbreviations: FAC(I)T-G/F = Functional Assessment of Cancer

Therapy-General/Fatigue Scale; N/A = Not applicable; pTNM = Classification of Malignant Tumors by histopathologic

examination. Missing data is not displayed. Metrical Values are displayed as means and standard deviations if not otherwise

described.

INTREST registry Saarland

registry

TMK

cohort

CM

trial

(N = 858) (N = 93,721) (N = 729) (N = 275)

Age at baseline 57.0 (11.6) N/A N/A 56.1 (11.0)

Age at first cancer diagnosis 56.9 (11.5) 63.7 (13.9) 26.8 (5.4) 52.9 ( N/A)

Tumor type

Invasive ductal carcinoma 78.9 % 74.0 % N/A 75.6 %

Invasive lobular carcinoma 15.8 % 12.8 % N/A 15.6 %

Inflammatory breast cance

r

0 % 0 % N/A 0 %

Other BCs 5.3 % 3.3 % N/A N/A

Tumor stage (pTNM)

Stage I 31.3 % 39.3 % 26.6 % 39.3 %

Stage II 24.3 % 39.4 % 46.2 % 38.5 %

Stage III 4.3 % 13.7 % 15.9 % 9.1 %

Tumor grading

GX 0.1 % 4.7 % N/A N/A

G1 13.4 % 3.9 % N/A 10.9 %

G2 55.2 % 53.3 % N/A 45.1 %

G3 31.2 % 28.2 % N/A 44.4 %

Tumor receptor subtype

Luminal A 69.3 % N/A 59.9 % N/A

Luminal B 12.5 % N/A 15.5 % N/A

HER2-

p

ositive 3.5 % N/A 6.7 % N/A

Triple-negative 14.7 % N/A 16.2 % N/A

Menopause

Pre-/perimenopausal 38.1 % N/A 34.4 % 40.4 %

Postmenopausal 61.9 % N/A 65.6 % 52.7 %

FACT-G at baseline 78.8 (15.7) N/A 75.7 (15.7) 76.2 ( N/A)

FACIT-F subscale at baseline 37.8 (10.5) N/A N/A 36.4 (11.1)

Technical Realization and First Insights of the Multicenter Integrative Breast Cancer Registry INTREST

303

Our analyses show that our sample of women

suffering on breast cancer does not significantly differ

from other registry and pragmatic trial data of breast

cancer patients in Germany with respect to main

sociodemographic and clinical cancer data.

However, completeness particularly in tumor

classification currently is a major limitation, which

has also been reported in other registries (Ording et

al., 2012; Ramos et al., 2015). Whether technical so-

lutions in the sense of machine learning algorithms,

e.g., to predict missing TNM-staging (Appelbaum et

al., 2023), might be a helpful tool will be discussed

when analyzing the missing data more deeply.

In the next step of the analysis, which is planned

when the data of the respective follow-up assessment

points have been entered into the database and mis-

sing data have been imputed according to the strate-

gies described in Haller et al. (2021), logistic regres-

sion analyses and other predictive models will be run

to identify potential responders and non-responders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the scientific assistants

who actively supported us in entering the patient data.

REFERENCES

Appelbaum, S., Krüerke, K., Baumgartner, S., Schenker,

M., Ostermann, T. (2023). Development,

implementation and validation of a stochastic

prediction model of the TNM classification for missing

values in large data sets in a hospital cancer registry. In

Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference

on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies

- HEALTHINF.

Alsanad, S. M., Williamson, E. M., & Howard, R. L.

(2014). Cancer patients at risk of herb/food

supplement-drug interactions: A systematic review.

Phytotherapy Research : PTR, 28(12), 1749–1755.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5213

Attkisson, C. C., & Zwick, R. (1982). The Client

Satisfaction Questionnaire: Psychometric properties

and correlations with service utilization and

psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and program

planning, 5(3), 233-237.

Ben-Arye, E., Samuels, N., Goldstein, L. H., Mutafoglu, K.,

Omran, S., Schiff, E., Charalambous, H., Dweikat, T.,

Ghrayeb, I., Bar-Sela, G., Turker, I., Hassan, A.,

Hassan, E., Saad, B., Nimri, O., Kebudi, R., &

Silbermann, M. (2016). Potential risks associated with

traditional herbal medicine use in cancer care: A study

of middle eastern oncology health care professionals.

Cancer, 122(4), 598–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/

cncr.29796

Bode, A. M., & Dong, Z. (2015). Toxic phytochemicals and

their potential risks for human cancer. Cancer

Prevention Research, 8(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/

10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0160

Book, K., Marten‐Mittag, B., Henrich, G., Dinkel, A.,

Scheddel, P., Sehlen, S., ... & Herschbach, P. (2011).

Distress screening in oncology—evaluation of the

Questionnaire on Distress in Cancer Patients—short

form (QSC‐R10) in a German sample. Psycho‐

Oncology, 20(3), 287-293.

Boon, H. S., Olatunde, F., & Zick, S. M. (2007). Trends in

complementary/alternative medicine use by breast

cancer survivors: Comparing survey data from 1998

and 2005. BMC Women's Health, 7(1), 4.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-7-4

Bredle, J. M., Salsman, J. M., Debb, S. M., Arnold, B. J., &

Cella, D. (2011). Spiritual well-being as a component

of health-related quality of life: the functional

assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-

being scale (FACIT-Sp). Religions, 2(1), 77-94.

Brucker, P. S., Yost, K., Cashy, J., Webster, K., & Cella, D.

(2005). General population and cancer patient norms

for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-

General (FACT-G). Evaluation & the health

professions, 28(2), 192-211.

Chang, V. T., Hwang, S. S., Feuerman, M., Kasimis, B. S., &

Thaler, H. T. (2000). The memorial symptom assessment

scale short form (MSAS‐SF) validity and reliability.

Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the

American Cancer Society, 89(5), 1162-1171.

Cheng, K. K. F., & Yeung, R. M. W. (2013). Impact of

mood disturbance, sleep disturbance, fatigue and pain

among patients receiving cancer therapy. European

Journal of Cancer Care, 22(1), 70–78.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01372.x

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G., & Moons, K.

G. (2015). Transparent reporting of a multivariable

prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis

(TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Journal of British

Surgery, 102(3), 148-158.

Courtier, N., Gambling, T., Enright, S., Barrett-Lee, P.,

Abraham, J., & Mason, M. D. (2013). Psychological

and immunological characteristics of fatigued women

undergoing radiotherapy for early-stage breast cancer.

Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(1), 173-181.

Craig, C. L., Marshall, A. L., Sjöström, M., Bauman, A. E.,

Booth, M. L., Ainsworth, B. E., ... & Oja, P. (2003).

International physical activity questionnaire: 12-

country reliability and validity. Medicine and science in

sports and exercise, 35(8), 1381-1395.

Dusek, J. A., Abrams, D. I., Roberts, R., Griffin, K. H.,

Trebesch, D., Dolor, R. J., Wolever, R. Q., McKee, M.

D., & Kligler, B. (2016). Patients receiving integrative

medicine effectiveness registry (primier) of the

bravenet practice-based research network: Study

protocol. BMC Complementary and Alternative

Medicine, 16(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-

016-1025-0

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

304

Ferlay, J., Colombet, M., Soerjomataram, I., Parkin, D. M.,

Piñeros, M., Znaor, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Cancer

statistics for the year 2020: An overview. International

Journal of Cancer, 149(4), 778-789.

Fraser, L., Burnell, M., Salter, L. C., Fourkala, E. O., Kalsi,

J., Ryan, A., ... & Menon, U. (2014). Identifying

hopelessness in population research: a validation study

of two brief measures of hopelessness. BMJ open, 4(5),

e005093.

Greenlee, H., Balneaves, L. G., Carlson, L. E., Cohen, M.,

Deng, G., Hershman, D., Mumber, M., Perlmutter, J.,

Seely, D., Sen, A., Zick, S. M., & Tripathy, D. (2014).

Clinical practice guidelines on the use of integrative

therapies as supportive care in patients treated for breast

cancer. JNCI Monographs, 2014(50), 346–358.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu041

Grimm, D., Voiss, P., Paepke, D., Dietmaier, J., Cramer,

H., Kümmel, S., Beckmann, M. W., Woelber, L.,

Schmalfeldt, B., Freitag, U., Kalder, M., Wallwiener,

M., Theuser, A.‑K., & Hack, C. C. (2021).

Gynecologists' attitudes toward and use of

complementary and integrative medicine approaches:

Results of a national survey in Germany. Archives of

Gynecology and Obstetrics, 303(4), 967–980.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-020-05869-9

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in

two emotion regulation processes: implications for

affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of

personality and social psychology, 85(2), 348.

Haller, H., Voiß, P., Cramer, H., Paul, A., Reinisch, M.,

Appelbaum, S., Dobos, G., Sauer, G., Kümmel, S., &

Ostermann, T. (2021). The intrest registry: Protocol of

a multicenter prospective cohort study of predictors of

women's response to integrative breast cancer

treatment. BMC Cancer, 21(1), 724. https://doi.

org/10.1186/s12885-021-08468-2

Hoque, N., Bhuyan, M. H., Baishya, R. C., Bhattacharyya,

D. K., & Kalita, J. K. (2014). Network attacks:

Taxonomy, tools and systems. Journal of Network and

Computer Applications, 40, 307–324. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.jnca.2013.08.001

Jansen, L., Holleczek, B., Kraywinkel, K., Weberpals, J.,

Schröder, C. C., Eberle, A., et.al. (2020). Divergent

patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence, mortality

and survival among older women in Germany and the

United States. Cancers, 12(9), 2419.

Jensen, O. M., Whelan, S., Jensen, O., Parkin, D.,

MacLennan, R., Muir, C., & Skeet, R. (1991). Planning

a cancer registry. IARC Sci. Publ, 95, 22-28.

Koenig, C. J., Ho, E. Y., Trupin, L., & Dohan, D. (2015).

An exploratory typology of provider responses that

encourage and discourage conversation about

complementary and integrative medicine during routine

oncology visits. Patient Education and Counseling,

98(7), 857–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.

02.018

Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie. (2017). S3-Leitlinie

Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge

des Mammakarzinoms (Version 4.0, AWMF

Registernummer: 032-045OL). Retrieved from

http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/

mammakarzinom/

Lie D, Boker J. Development and validation of the CAM

health belief questionnaire (CHBQ) and CAM use and

attitudes amongst medical students. BMC Med Educ.

2004;4(1):1–9.

Lyman, G. H., Greenlee, H., Bohlke, K., Bao, T.,

DeMichele, A. M., Deng, G. E., Fouladbakhsh, J. M.,

Gil, B., Hershman, D. L., Mansfield, S., Mussallem, D.

M., Mustian, K. M., Price, E., Rafte, S., & Cohen, L.

(2018). Integrative therapies during and after breast

cancer treatment: Asco endorsement of the SIO clinical

practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology,

36(25), 2647–2655. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.

79.2721

Marschner, N., Trarbach, T., Rauh, J., Meyer, D., Müller-

Hagen, S., Harde, J., et al. (2019). Quality of life in pre-

and postmenopausal patients with early breast cancer: a

comprehensive analysis from the prospective MaLife

project. Breast cancer research and treatment, 175(3),

701-712.

Molassiotis, A., Fernández-Ortega, P., Pud, D., Ozden, G.,

Scott, J. A., Panteli, V., Margulies, A., Browall, M.,

Magri, M., Selvekerova, S., Madsen, E., Milovics, L.,

Bruyns, I., Gudmundsdottir, G., Hummerston, S.,

Ahmad, A. M.‑A., Platin, N., Kearney, N., & Patiraki,

E. (2005). Use of complementary and alternative

medicine in cancer patients: A European survey. Annals

of Oncology, 16(4), 655–663. https://doi.org/10.1093/

annonc/mdi110

Ording, A. G., Nielsson, M. S., Frøslev, T., Friis, S., Garne,

J. P., & Søgaard, M. (2012). Completeness of breast

cancer staging in the Danish Cancer Registry, 2004–

2009. Clinical epidemiology, 4(Suppl 2), 11.

Ostermann, T., Ehlers, J. P., Warzecha, M., Hohenberg, G.,

& Zupanic, M. (2018). Development of an Online-

System for Assessing the Progress of Knowledge

Acquisition in Psychology Students. Data 2018:

Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on

Data Science, Technology and Applications: 77–82.

https://doi.org/10.5220/0006892500770082

Paepke, D., Wiedeck, C., Hapfelmeier, A., Karmazin, K.,

Kiechle, M., & Brambs, C. (2020). Prevalence and

predictors for nonuse of complementary medicine

among breast and gynecological cancer patients. Breast

Care (Basel, Switzerland), 15(4), 380–385.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000502942

Patrick, D. L., Ferketich, S. L., Frame, P. S., Harris, J. J.,

Hendricks, C. B., Levin, B., Link, M. P., Lustig, C.,

McLaughlin, J., Ried, L. D., Turrisi, A. T., Unützer, J.,

& Vernon, S. W. (2003). National institutes of health

state-of-the-science conference statement: Symptom

management in cancer: Pain, depression, and fatigue,

July 15-17, 2002. Journal of the National Cancer

Institute, 95(15), 1110–1117. https://doi.org/10.1093/

jnci/djg014

Quandt, S. A., Verhoef, M. J., Arcury, T. A., Lewith, G. T.,

Steinsbekk, A., Kristoffersen, A. E., ... & Fønnebø, V.

(2009). Development of an international questionnaire

to measure use of complementary and alternative

Technical Realization and First Insights of the Multicenter Integrative Breast Cancer Registry INTREST

305

medicine (I-CAM-Q). The Journal of Alternative and

Complementary Medicine, 15(4), 331-339.

Ramos, M., Franch, P., Zaforteza, M., Artero, J., & Durán,

M. (2015). Completeness of T, N, M and stage grouping

for all cancers in the Mallorca Cancer Registry. BMC

cancer, 15(1), 1-6.

Richards, M. (2015). Software architecture patterns,

O'Reilly Media, Inc. Sebastopol, 1

st

edition.

Samuels, N., Ben-Arye, E., Maimon, Y., & Berger, R.

(2017). Unmonitored use of herbal medicine by patients

with breast cancer: Reframing expectations. Journal of

Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 143(11), 2267–

2273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-017-2471-x

Schad, F., Axtner, J., Happe, A., Breitkreuz, T., Paxino, C.,

Gutsch, J., Matthes, B., Debus, M., Kröz, M., Spahn,

G., Riess, H., Laue, H.‑B. von, & Matthes, H. (2013).

Network oncology (no)--a clinical cancer register for

health services research and the evaluation of

integrative therapeutic interventions in anthroposophic

medicine. Forschende Komplementarmedizin (2006),

20(5), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356204

Schalet, B. D., Pilkonis, P. A., Yu, L., Dodds, N., Johnston,

K. L., Yount, S.,et al. (2016). Clinical validity of

PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse

clinical samples. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 73,

119-127.

Schröder, H., Fitó, M., Estruch, R., Martínez‐González, M.

A., Corella, D., Salas‐Salvadó, J., et al. (2011). A short

screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet

adherence among older Spanish men and women. The

Journal of nutrition, 141(6), 1140-1145.

Schulz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2003). Social support in

coping with illness: the Berlin Social Support Scales

(BSSS). Diagnostica, 49(2), 73-82.

Stafford, L., Judd, F., Gibson, P., Komiti, A., Quinn, M., &

Mann, G. B. (2014). Comparison of the Hospital

Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Center for

Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for detecting

depression in women with breast or gynecologic

cancer. General hospital psychiatry, 36(1), 74-80.

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M.,

Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global

cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of

incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in

185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians,

71(3), 209-249.

Singer, S., Das-Munshi, J., & Brähler, E. (2010).

Prevalence of mental health conditions in cancer

patients in acute care--a meta-analysis. Annals of

Oncology : Official Journal of the European Society for

Medical Oncology, 21(5), 925–930. https://doi.org/

10.1093/annonc/mdp515

Thewes, B., Butow, P., Zachariae, R., Christensen, S.,

Simard, S., & Gotay, C. (2012). Fear of cancer

recurrence: a systematic literature review of self‐report

measures. Psycho‐oncology, 21(6), 571-587.

Witt, C. M., Außerer, O., Baier, S., Heidegger, H., Icke, K.,

Mayr, O., et al. (2015). Effectiveness of an additional

individualized multi-component complementary

medicine treatment on health-related quality of life in

breast cancer patients: a pragmatic randomized trial.

Breast cancer research and treatment, 149(2), 449-460.

Yost, K. J., & Eton, D. T. (2005). Combining distribution-

and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally

important differences: the FACIT experience.

Evaluation & the health professions, 28(2), 172-191.

Yu, L., Buysse, D. J., Germain, A., Moul, D. E., Stover, A.,

Dodds, N. E.,et.al.. (2012). Development of short forms

from the PROMIS™ sleep disturbance and sleep-

related impairment item banks. Behavioral sleep

medicine, 10(1), 6-24.

Zeller, T., Muenstedt, K., Stoll, C., Schweder, J., Senf, B.,

Ruckhaeberle, E., Becker, S., Serve, H., & Huebner, J.

(2013). Potential interactions of complementary and

alternative medicine with cancer therapy in outpatients

with gynecological cancer in a comprehensive cancer

center. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical

Oncology, 139(3), 357–365.

HEALTHINF 2023 - 16th International Conference on Health Informatics

306