An Analysis of Cybersecurity Awareness Efforts for Swiss SMEs

Ciar

´

an Bryce

University of Applied Sciences (HES-SO), Geneva, Switzerland

Keywords:

Security, Incentive, Risk Management, Awareness.

Abstract:

This paper analyzes cybersecurity awareness efforts for SMEs in Switzerland. We highlight some weaknesses

in these efforts and propose avenues for improvement. Compared to existing work, e.g., (Alahmari and Dun-

can, 2020), we focus on attitudes and experience of experts trying to bring security to organizations rather than

the organizations themselves.

1 INTRODUCTION

SMOs

1

have a number of quality cybersecurity solu-

tions at their disposal. These range from IT tools (e.g.,

free and open-source tools for VPN, IAM, PAM, pen-

testing, etc.) to support structures (trainings, knowl-

edge portals, awareness programs, helplines, etc.). At

the same time, the Cyber-Safe Association reports

that 1 in 3 Swiss SMOs have already been the vic-

tim of cyberattacks. 15% of companies train their

employees in good cybersecurity practices, yet 100%

of organizations are the subject of phishing attempts.

For more than 1/4 of cyberattack victims, recovery

costs exceed 10 000 CHF

2

. A US report mentions that

60% of companies that suffer a cyber-attack go out of

business within a year (Team, 2021).

To borrow a term from the health domain, there

are inefficient clinical pathways (Kinsman et al.,

2010) from cybersecurity providers to SMOs regard-

ing understanding and application of cyber-health

principles. We use the term provider to denote those

responsible for encouraging and implementing secu-

rity – solution providers, system administrators, re-

searchers, governments, etc.

This paper analyzes measures that encourage cy-

bersecurity in SMOs. This topic has been covered in

the literature, e.g., (Ponsard et al., 2019; Alahmari and

Duncan, 2020), but the focus has generally been on

how companies perceive risks and implement prac-

tices. This paper intentionally focuses on providers

for two reasons. First, they are the experts and, like in

the health domain, there can be a difference between

1

Small and Medium sized Organizations includes ad-

ministrations and non-profit organizations as well as SMEs.

2

https://www.cyber-safe.ch

how organizations perceive risks and the risks them-

selves. Second, providers must develop more coor-

dinated actions if cybersecurity practices in organiza-

tions are to become more effective, so it is important

to gauge their viewpoints

The methodology used was to hold interviews

with over 30 Swiss actors in the socioeconomic do-

main about their perspective on the problem. The ac-

tors came from domains as diverse as chambers of

commerce, banking, security solution providers, le-

gal, policing, insurance, and consulting.

2 METHODOLOGY

The methodology adopted was to interview socio-

economic actors regarding their perspective on the cy-

bersecurity situation in SMOs. We have explicitly fo-

cused on actors who play a provider role. In the end,

35 actors were interviewed. The interviewees cho-

sen work on some aspect of bringing cybersecurity to

SMOs. Alternatively, interviewees have some role in

relation to influencing behaviors among organizations

or the public at large – three interviewees come from

the health domain, one from the advertisement indus-

try and another from the tax service industry. The

profiles of the interviewees are presented in Table 2.

When referenced in the paper, the notation “(2)” is

used (for interviewee 2 in this case).

We have striven for a meaningful number of in-

terviews (Guest et al., 2006). Though we chose 35

interviewees in the end, the intention was a purposive

sample – where interviewees were chosen for specific

qualities (role, experience, and agency) – rather than

a probabilistic sampling. The interviewees include

Bryce, C.

An Analysis of Cybersecurity Awareness Efforts for Swiss SMEs.

DOI: 10.5220/0011631100003405

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2023), pages 381-388

ISBN: 978-989-758-624-8; ISSN: 2184-4356

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

381

managers at chambers of commerce, researchers, in-

surers, owners of security companies and various ex-

perts. They are experts in aspects of security and

whose opinion is likely to be listened to by SMOs

(agency). Probabilistic sampling is useful for gather-

ing feedback directly from SMEs such as their per-

spective on the cybersecurity crisis, e.g., (Huaman

et al., 2021; Pugnetti and Casi

´

an, 2021; Zec, 2015).

The goal of our study was not to determine a consen-

sus, but to define and delimit the feedback of experts

on the problem. Nonetheless, we felt that we have

achieved a degree of data saturation, as the later inter-

views brought less insight than the earlier ones.

The interviews were conducted between October

2020 and June 2022. They took the form of an open

one-on-one discussion with a duration of at least 30

minutes. Some interviewees were interviewed sev-

eral times. A workshop with interviewees took place

in December 2021. In the discussions, interviewees

were asked to explain what made their job difficult in

relation to encouraging cybersecurity, and what they

felt could improve the situation. Key replies form the

code book of our study, and are used to structure the

analysis of the interviews in the following sections.

The elements of the code book are the paragraph ti-

tles in Sections 3.2 to 3.6 and are listed in Table 1.

From an ethics point of view, the names of the in-

terviewees are hidden in this paper. No interviewee

asked for anonymity, and the opinions conveyed cor-

respond to opinions that they have also expressed in

public as part of their job.

3 ANALYSIS OF AWARENESS

EFFORTS

Efforts to get SMOs to adopt security measures gener-

ally and historically begin with awareness programs.

The Swiss Confederation – notably through the ef-

forts of the Swiss National Cyber-Security Center –

is putting great emphasis into cyber-risks awareness.

Chambers of Commerce and similar organizations

also are making significant efforts to raise awareness

in companies through the organization of events.

Awareness is only the first step for an SMO to

have a cybersecurity culture. This is also a lesson

learned in the health domain, where informing a per-

son of the risk of bad behavior like smoking is not

considered enough since the person must have the

will and the means to adopt a healthy behavior. For

cybersecurity, the end-goal for SMOs is a cybersecu-

rity culture where cyber-risks are managed in an au-

tonomous manner, and where there is regular prac-

tice of defense and recovery procedures. Awareness

Table 1: Codebook for Interviews.

Stage Response

Awareness Too many companies

Limited attention

Fuzzy data

Message imparted 6= message heard

Understanding Belief it’s an IT issue

Rejection of negative messages

Abstract objectives

“Swissitude”

Poor risk assessment

Will to act Risk tolerance

Message incoherency

Action Poor IT Training

Perceived Costs

Mistrust of providers

Empowerment Absence of helpdesk

Absence of follow-up

No Sustainable Business Models

is only the first step for SMOs in this journey towards

the equivalent to what in the health domain is called

empowerment (Nutbeam, 1998).

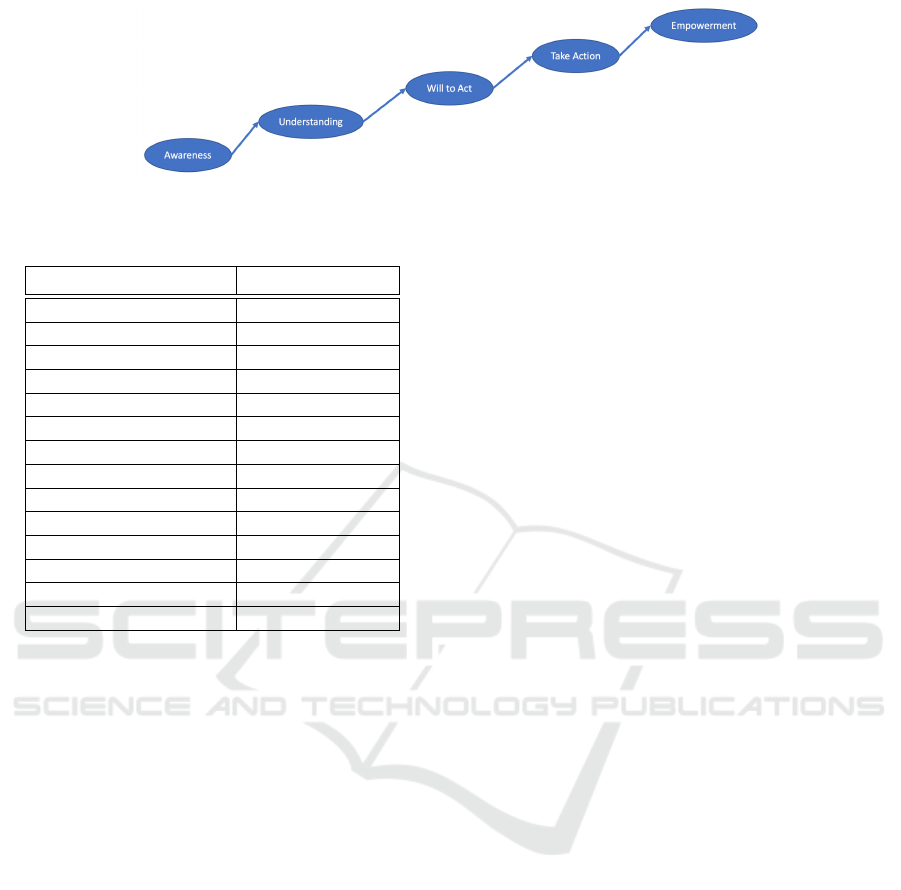

In the cybersecurity context, we can break down

the stages between awareness and the end-goal of em-

powerment, as illustrated in Figure 1. This model

is loosely based on the Trans-theoretical Model

3

in

the health domain that describes the stages a patient

undergoes in therapy (Prochaska and DiClemente,

2005). We chose the model to illustrate that mak-

ing SMOs aware of cybersecurity risks is only the

start of a process. In other words, the question of

how to make SMOs aware is not the only question

we can ask ourselves. Identifying the stages allows

us to raise other questions like “who pays for secu-

rity?” and “how do we enable SMOs to address occa-

sional queries they have on security matters?”. Thus,

efforts to make SMOs secure should be stage matched

to where they are on the model’s curve.

3.1 Cybersecurity Stages

We adapted the Trans-theoretical Model to what we

see as the main stages of an organization’s cybersecu-

rity journey.

Awareness. The SMO learns about threats like ran-

somware and denial of service attacks. The SMO

understands the motivations of criminal organizations

and state actors and accepts that everyone is a target.

3

Medical researchers chose this name since the model

brings together several theories in psychotherapy.

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

382

Figure 1: Stages in Creating a Cybersecurity Culture in SMOs.

Table 2: Interviewee Profiles.

Domain ID

Technology Start-up 2

Health 6, 16, 26

Academic 17, 28

Police 24, 25

Chamber of Commerce 5, 8, 13

Public Administration 11, 24, 27, 30

Security Firm 2, 9, 17, 18, 31

Consultant 1, 4, 9, 10, 23, 29

Major IT provider 12, 22, 35

Insurance and Risk 1, 15, 32, 34

NGO 29

Law 20, 31

Security Foundation 3, 4, 21

Other 7, 14, 19, 33

Understanding. The SMO owner can measure the

impact of a cyber-attack on his own assets and busi-

ness. This measure can be in terms of company down-

time, number of employees to mobilize to recover

from an attack, or a monetary cost.

Will to Act. The SMO refuses to accept the cyber-

security risks and decides to act to mitigate these. The

SMO is willing to define a security policy and to in-

vest resources.

Take Action. The SMO acts by adopting a techni-

cal and organizational security solution. This can in-

clude purchasing a tool from a solution provider, hir-

ing a specialist, or defining and implementing a secu-

rity policy.

Empowerment. In this end state, there is a shift

in thinking within the SMO. Cybersecurity practices

are as integrated in the operation of the company as

accounting and salary management. Cyber-defense

mechanisms are in place and the business continuity

plan includes a rehearsed data restoration procedure.

The SMO can keep up to date about current risks and

gets informed of threats that it may not know about.

3.2 Resistors to Awareness

The first step of the cybersecurity journey is to make

companies aware of cyber-risks. Many of the inter-

viewees are involved in such efforts.

Too Many Companies? There are a lot of organi-

zations to make aware: 48’000 companies in Geneva

alone. One chamber of commerce has organized cy-

bersecurity events attended by 1’200 companies over

the last 10 years. Yet, 1’200 out of 48’000 is too low

a burn rate (8).

This raises the question of a more strategic target-

ing for awareness. For instance, there might be 1’000

bankers in the canton who organize loans to compa-

nies. An awareness program for 1’000 bankers is lo-

gistically simpler than a program for 48’000 compa-

nies (15), and can be more worthwhile if the bankers

can be convinced to include cybersecurity in the due

diligence of their clients (18).

Attention is a Limited and Highly Solicited Re-

source. The goal of every SME is to sell products.

Unless the company suffers a cyber-attack, then im-

plementing cybersecurity can get pushed out of the

list of priorities. A chamber of commerce reported

having organized an event on cybersecurity in 2016

that was very well attended; a similar event in 2020

was cancelled due to lack of inscriptions (5). Other

interviewees reported a similar disinterest in recent

cybersecurity events.

Since 2020, SMOs are obviously attributing much

attention to the Covid-19 crisis. Also, data protection

and regulations are not the only concerns for SMOs.

Depending on the sector, SMOs need to be concerned

with environmental emissions, taxation, Know-your-

customer rules, etc.

Fuzzy Data. The overall cybersecurity picture in

Switzerland can be hard to read since the cantons keep

statistics rather than the Swiss central government.

The figures for cantons are obviously lower than for

An Analysis of Cybersecurity Awareness Efforts for Swiss SMEs

383

the whole of Switzerland and this might lead SMOs

to underestimate the scale of the problem (25)

4

.

Further, many publications written for industry

give figures for the cost of cyber-attacks, e.g., “1% of

GDP”. However, it is often unclear what these costs

are, e.g., ransomware payments, capital, and opera-

tional spending on cybersecurity tools, losses incurred

from company downtime following a cyber-attack,

etc. It can also be unclear if the figures are for US

or worldwide companies. A precise cost methodol-

ogy of cyber-damage needs to be defined.

Part of the problem is the reluctance of SMOs to

report cyber-attacks. One study (Zec, 2015) explains

reluctance to report being caused by three factors: i)

fear of negative publicity, ii) lack of confidence in the

judiciary to do something about the attack, and iii) un-

derestimation of the seriousness of the attack. Having

the real figures could make the awareness campaign

more effective. In (Kuderli and Neher, 2020), the au-

thors cite the absence of a duty to report in Switzer-

land as the main reason why the current figures under-

estimate the impact of cyber-attacks. Obliging com-

panies to report could bring clarity to the situation.

Message Imparted Versus Message Heard. What

is said to SMOs is not necessarily the same thing as

what SMOs hear and understand (17). The message

can get skewed in “IT talk” translation. A marketing

specialist suggested that there is a lot of “geek speak”

in solution provider marketing (19). He mentions that

windows salesmen never start their sales pitch with

“this is a great window”; they start by saying that “you

can deduct installation costs from taxes and save up to

30% on your annual heating bill”. Security providers

have a hard sell, as they are selling a product that fun-

damentally, people do not want.

In that regard, Cyber-Safe highlights that the cy-

bersecurity message being given to SMOs is too IT

oriented and therefore not audible enough to company

owners (18). The IT message speaks of viruses, de-

nial of service attacks, etc. A company owner rea-

sons in terms of the value of company assets, expected

revenue and expenditure. Audibility is therefore in-

creased by moving away from IT-based KPIs (e.g.,

number of phishing emails blocked) to business KPIs

(salary costs and expected revenue losses).

Ultimately, there is a need for more creativity in

finding ways to inform SMOs. An interesting effort

to increase understanding is the Bande Dessin

´

ee de la

S

´

ecurit

´

e (23) where the message is passed in a non-

traditional way for IT. Another incentive technique for

attention and learning is gaming (G

¨

oschlberger and

4

This situation is evolving with the implementation of a

new IT platform by the federal authorities.

Bruck, 2017). An example is a simple card game that

teaches social engineering attacks (car, ).

Cyber-insurers are now a precious resource for

SMO security awareness. They have information

about all declared cyber-attacks. Further, courtiers

visit all companies in Switzerland and present risks –

including cyber-risks. For example, insurers carry the

message that the Windows 7 operating system should

no longer be used (15). If an SMO refuses a cyber-

insurance contract, he does so after being informed of

the risks.

3.3 Resistors to Understanding

Understanding is the phase where the SMO owner

can measure the impact of cyber-risks on his business.

This may require effort but is a pre-requisite to being

able to act appropriately.

Belief that Security is an IT Issue. Cyber-attacks

aim to extract or damage data within the IT system

so this contributes to the belief that the attack can be

resolved by the “IT guy” (10). The problem is that at-

tacks will succeed, and the SMO must have a business

recovery plan that includes procedures for handling

client data leaks and resuming business.

Another problem is that many SMO managers as-

sume that their “IT guy” can handle security (18).

Partly due to the emergence of frameworks, IT is

now a large field. Even something as apparently

straightforward as maintaining a WordPress website

is not trivial, since there are many configuration files,

databases, extensions, and style files to maintain. Few

IT professionals can be expected to have knowledge

in all areas of IT that companies rely upon.

Awareness efforts and solution provider messag-

ing might be partly to blame here since they empha-

size mostly IT-based defense strategies. Other depart-

ments need to be involved, notably HR since they are

ultimately responsible for training employees (10).

Many argue that the cybersecurity manager should

be part of the board of the company (17)(23), though

given the often too technical orientation of this man-

ager, he or she is often poorly adapted to the sys-

temic role that board members should have (Atmani

and Flaurand, 2021).

Rejection of Negative Messages. As noted in the

health domain, there is a natural human tendency to

reject uncomfortable messages (6). A negative mes-

sage is generally acted upon when it becomes per-

sonalized. For instance, breast-cancer screening pro-

grams often struggle to attract women, and many

women who attend are close to someone who already

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

384

suffers from cancer. Similarly, graphic images on

cigarette boxes are not dissuading people from buy-

ing cigarettes (6). The image of the person on the

cigarette box needs to be replaced by the image of a

close friend or family member for the message to be

effective. Scare-mongering is generally considered

to be ineffective by healthcare providers and IT se-

curity experts alike (22)(26)(15)(29). We should at

least frame messages in a more pedagogical manner,

such as “would you manage client data without tak-

ing security precautions, if you would not drive a car

without insurance?” (19).

Abstract Objectives. Many companies see cyber-

security as something nebulous, and it can be difficult

for companies to visualize the danger (15)(12). The

attackers are portrayed as hooded and faceless, and

the measures we ask them to put in place can be diffi-

cult to sell since they cannot cover all the attack sur-

face. Resilience might be a more meaningful term to

use in SMO awareness programs (12).

A further difficulty is to concretely measure the

risk and the value of some solution. For instance, in

the context of the Paris Climate Agreement Accord

5

,

Switzerland wants to reduce its emission of green-

house gases by 50% by the year 2030 compared to

1990 levels. Even if achieving this is hard, the objec-

tive is simply stated, easily measurable and therefore

easier to mobilize interest in.

A measurable objective in the cybersecurity con-

text could be “one private disk per company”, “2

rehearsed data restorations (post-ransomware) per

year” (24), etc.

Swissitude. Citizens in Switzerland enjoy a rela-

tively high level of physical security and safety. It has

been suggested that SMO owners sometimes project

this sentiment of safety to the Internet world. It

is common to hear remarks from SMOs like “Why

would my company be attacked? We are only a small

company” (24). This sentiment has also been high-

lighted in another study on Swiss employee attitudes

to cyber-risks (Pugnetti and Casi

´

an, 2021).

Poor Risk Assessment. Despite best intentions, it

is possible for the SMO to make the wrong risk as-

sessment (impact and probability) (15). Audits and

labels are devised to detect these errors (21), but not

all organizations ask for these.

One interviewee highlighted a disparity between

the message given by auditors and the reality in com-

5

https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-

agreement/the-paris-agreement

panies (2). For instance, an audit might mark a com-

ponent as an accepted risk but this is the very com-

ponent through which an attack passes. An example

are administrators since they have too much privilege

and not enough safeguards. Also, too many cosmetic

solutions are proposed to companies (2).

3.4 Resistors to Will-to-Act

Despite understanding the risks to their own company,

SMO owners may choose to accept these risks, or

consider that they are not worth the cost of invest-

ment (23).

SMO owners are by nature open to risks. As one

SMO owner said: “if you are risk-averse, then be-

come an employee” (14). Another mentioned that

some companies do not care about the risks since

they believe that they could continue to function even

if attacks arise (9). Yet another perspective comes

from the health domain where treatment is endan-

gered when the patient believes that the “treatment is

worse than the illness”, even if the treatment is effec-

tive (26). A related perspective here is the concern

that making backups is a throwback to an older IT,

and that it can be frustrating to change one’s way of

working to incorporate cyber-hygiene practices (28).

Another resistor is the coherency of the message

from providers. There is agreement in the health do-

main that the message given to a patient from differ-

ent healthcare providers (nurse, doctor, pharmacist,

...) needs to be coherent, as incoherencies under-

mine the credibility of the message (e.g., when the

pharmacist proposes a different remedy to medica-

tion a doctor prescribed). In the cybersecurity con-

text, providers (administrations, solution providers,

educators, chambers of commerce) must ensure the

coherency of their messaging.

The advantage of the EU’s General Data Protec-

tion Regulation (GDPR) is that it obliges companies

to act for security – the stick approach in place of the

carrot.

3.5 Resistors to Action

Poor IT Training. Many companies want to act but

ask “Ok, but what do we actually need to do?” (13).

Computer science degrees have been criticized for

not treating computer security enough (23). Until

recently at least, many IT graduates were unable to

define security policies or to design a secure infras-

tructure in a company. Also, not all IT professionals

understand the technical details of how attacks hap-

pen (2). There are not enough highly qualified per-

sonnel in Switzerland (23).

An Analysis of Cybersecurity Awareness Efforts for Swiss SMEs

385

There is good news on this issue, thanks largely to

the arrival of the GDPR. A new generation of com-

puter science students are learning that when build-

ing a full-stack Web service, instinctively, they must

factor in security (e.g., separate the DB tables hold-

ing personal client data, use encrypted storage). This

evolution in thinking is analogous to architects who

instinctively include fire escapes in their building de-

signs. If a change occurs to the budget of a building,

it would never occur to an architect to remove the fire

escapes to save money. Soon, it will never occur to

a computer scientist to forego security to cut projects

costs or to be ready for a release date.

This also responds to a common criticism of many

IT systems since the administrator has all privileges in

the system, so a compromise of an administrator ac-

count leads to a major security breach (e.g., a sudo

account in Linux or Administrator account in Win-

dows Server). This binary model also means that ad-

ministrators have access to too much data. This point

was again mentioned by the interviewees (2) and even

raised in a Swiss court case:

“There are huge gaps in the ethics of computer

scientists. In their training, there is no course

on this subject. When I question them, I re-

alize that most consider it completely normal

for them to have all accesses” – Jean Treccani

Perceived Costs. SMOs are often hesitant about the

cost of security implementation: a company will tend

towards the best price ahead of the best security (10).

Even if there are many free tools available (capex),

there is the operational cost (opex) of understanding

and maintaining these. That said, it might be inter-

esting to distinguish SMOs from micro-SMOs (3),

where the former handle security in-house while the

latter tend more to outsource to providers. These con-

cerns raise two questions:

1. Given the importance of cybersecurity to SMOs,

who should pay for security? If cybersecurity

spending is obliged of companies, then a tax credit

model is worth investigating – this model is in

place in the US state of Maryland since 2018

6

.

Tax and insurance are the two payment modes that

companies are used to where there is no immedi-

ately obvious return on investment. Tax credits,

for instance, are recommended in a US report by

the Cyber-Readiness Institute (Team, 2021).

2. How much does operational security cost any-

way? There is no standard figure that can be

6

https://commerce.maryland.gov/fund/programs-for-

businesses/buy-maryland-cybersecurity-tax-credit

given to an SMO for costs. Given that many secu-

rity tools are free, it is worthwhile defining a cost

model. This is something that insurance compa-

nies are interested in (32).

Hesitations About Solution Providers. Many

SMOs do not feel competent enough to decide on the

security tools they need. They rely on the advice of

a security solution provider for this. This can cre-

ate skepticism since the SMO cannot be sure that the

most appropriate solution is being provided (11)(22)

7

.

Providers are sometimes perceived as being too tech-

nical and not immersed enough in the operational and

business model of their client. On a related matter,

one interviewee reported how ethical hacking com-

panies had a negative impact by scaremongering and

creating a sentiment of continued vulnerability (23).

3.6 Resistors to Empowerment

Once a company has made its initial investment in

tools and processes for cybersecurity, it needs to

maintain its security preparedness.

Absence of a Helpdesk Structure. Companies

need accompaniment or advice over solutions. They

might have an occasional query on how to implement

some security feature or need to be informed of a par-

ticular malware to which they may be vulnerable.

One interviewee is developing a helpdesk model

for Value-Added Tax declarations. Like for cyberse-

curity, support for VAT needs to be continuous and

occasional. It is hard for security providers to pro-

vide this support since most of the 5’000 providers in

Switzerland have 3 employees or less. Nonetheless,

cyber-insurance companies now include a helpdesk in

their offers. The helpdesk is particularly useful after

an incident in guiding the client (15).

Absence of Follow-up. Once an SMO has adopted

a solution, label or cyber-insurance policy, its good

practices with respect to the solution need to be ver-

ified (18). In some countries, the health authority

uses a being remembered model (6), where patients

are regularly reminded for checkups (and can billed

even if they do not show up for the checkup). La-

bel providers limit the duration of the label so that the

company periodically demonstrates its ability to con-

form to the label requirements.

7

One auditor reported that a common motivation for

asking for an audit was to evaluate the company’s security

provider (18).

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

386

Sustainable Business Models for Providers. SMO

empowerment must provide the possibility of a sus-

tainable business model for providers also. The SMO

market is not necessarily lucrative enough. One inter-

viewee reported a phenomenon where SMEs are not

considered as good clients by security providers since

revenue is generally low (18). Providers that target

SMEs and whose solution becomes successful, often

adapt their solutions to bigger sized clients for eco-

nomic reasons. Another interviewee mentioned that

his company was created to provide security consult-

ing to SMOs, but nearly the whole of his revenue over

the past 5 years has come from larger structures (31).

Smaller structures are harder to work with because fi-

nancial negotiations are more complicated

Further, in a domain where innovation is consid-

ered a key factor to provider success, SMOs still re-

quire solutions for older legacy infrastructures and

technologies. Updating from older systems requires a

critical mass of competence and resources that might

not be available within an SMO. Research funding

agencies like InnoSuisse and the Swiss National Sci-

ence Foundation prioritize innovative technology so-

lutions (30), whereas, arguably, SMOs really require

better engineered packages of existing solutions. Of

course, innovative solutions do have a role to play,

since better than making consumers aware of security

is the idea of making security automatically and in-

visibly implemented (4). Virtual environments like

Docker are good examples: instead of patching an

OS, one simply deploys a new virtual environment

which does not contain the vulnerability, i.e., the

patching of security fixes is automatically handled.

Another example is the automatic handling of back-

ups by cloud providers.

4 RELATED WORK

One report (Pugnetti and Casi

´

an, 2021) examines atti-

tudes to cyber-risks in Swiss firms from an employee

perspective. The study found that in the surveyed

companies, employees felt aware of the threat posed,

but felt that their company was not large enough to be

targeted. They also relied on external IT providers to

solve the problem. The authors identify this as a “sys-

temic weakness”, underlying that we “readily place

ourselves in the care of doctors and nurses and would

not self-medicate if we were seriously ill”. The report

urges more training within companies so that employ-

ees take ownership of cyber-risks.

A study of security preparedness for Slovakian

SMEs is made in (Zec, 2015). They identify three

areas where SMEs need to be effective: i) technical

competence, ii) organizational ability and iii) psycho-

logical maturity. The latter addresses the readiness

of IT people to address a cybersecurity issue when it

is not part of their job description, or when this in-

volves going against management or working over-

time. The report highlights weaknesses in the compa-

nies surveyed on all three levels, though the number

of companies chosen is small.

A study of German SME preparedness (aware-

ness, measures taken, and attacks suffered) is reported

in (Huaman et al., 2021). 5000 companies were inter-

viewed using computer-assisted telephone interviews.

The companies come from all economic sectors and

have up to 500 employees. Among the findings,

the study found that technical measures were widely

used but operational measures (written security pol-

icy, training, simulations) were especially absent in

smaller firms. Those companies that do have opera-

tional measures often have it for compliance reasons.

Companies with operational measures fared better un-

der attacks. The report also found that the risk of tar-

geted attacks is underestimated by all companies.

A study of Belgian SMEs (Ponsard et al., 2019)

concluded that cybersecurity awareness should con-

sider both the individual and the organization. Aware-

ness should deal with knowledge artifacts but also at-

titudes (i.e., feelings and emotions) and behaviors (ac-

tivities and risk-taking actions linked to security). The

techniques studied are awareness campaigns, general

information and guides, personae, quizzes, assess-

ments and audits, training courses with tool support.

They conclude that a mix of techniques is required

and events require good group dynamics.

The Swiss, Slovakian and German studies aim

to understand the SME perspective on cybersecurity.

These studies are important, but the issue with a spe-

cialized topic like security is that the perceived prob-

lem does not always correspond to the real problem.

Our study has taken a complementary approach of

questioning experts who are working to improve the

security of SMEs.

SMO cybersecurity would be improved if soft-

ware development methods could ensure fewer vul-

nerabilities. Several ethnographic studies have been

conducted to understand how software developers

can be made more aware of secure coding practices,

e.g., (Tuladhar et al., 2021; Weir et al., 2018). Among

the findings, software development teams best adopt

security practices using the same learning dynamics

that they use when adopting some new technology

(like a Web framework). It is better to include secure

coding from the start rather than having to modify ex-

isting code, especially when this code is already in

production. Developers are afraid of upsetting clients

An Analysis of Cybersecurity Awareness Efforts for Swiss SMEs

387

when working systems are modified (even if this is

to add security fixes). Experts who encourage secure

practices need to make a better effort at understanding

the developers’ issues for their message to be heard.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Organizations like chambers of commerce are mak-

ing great efforts to inform SMOs about cyber-risks

though inefficiencies remain. Among the lessons

learned in this study:

• Targeted awareness programs are worth inves-

tigating. An awareness program might target

bankers who give loans to companies and seek

to convince these bankers to ask for cybersecurity

guarantees as part of client due diligence.

• There is still a lot of geek speak and a tendency to

target IT to the detriment of others such as HR.

• Providers generally take little of the client risk,

and distrust of IT solution providers hampers

security efforts.

• A help-line service for organizations and ensur-

ing a coherent security message is transmitted to

organizations would be very useful.

• The greatest challenge to develop a business

model for companies creating solutions for

SMOs. Solution providers find it difficult to gen-

erate revenue from working with SMOs. While it

is critical to help SMOs, there is little economic

incentive to do so.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author is very grateful to the Hasler Foundation

for funding this research.

REFERENCES

Free social engineering playing cards. https://www.nixu.

com/blog/free-social-engineering-playing-cards. Ac-

cessed: 2010-09-30.

Alahmari, A. and Duncan, B. (2020). Cybersecurity risk

management in small and medium-sized enterprises:

A systematic review of recent evidence. In 2020 inter-

national conference on cyber situational awareness,

data analytics and assessment (CyberSA), pages 1–5.

IEEE.

Atmani, M. and Flaurand, V. (2021). La

cyber-s

´

ecurit

´

e : d

´

efi du management des

risques. PME Magazine 15, PME Magazine.

https://www.pme.ch/strategie/2021/11/30/la-

cybersecurite-defi-du-management-des-risques.

G

¨

oschlberger, B. and Bruck, P. A. (2017). Gamification

in mobile and workplace integrated microlearning. In

Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on

Information Integration and Web-based Applications

& Services, iiWAS 2017, Salzburg, Austria, December

4-6, 2017, pages 545–552.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many

interviews are enough? an experiment with data satu-

ration and variability. Field methods, 18(1):59–82.

Huaman, N., von Skarczinski, B., Stransky, C., Wermke,

D., Acar, Y., Dreißigacker, A., and Fahl, S. (2021).

A large-scale interview study on information security

in and attacks against small and medium-sized enter-

prises. In Bailey, M. and Greenstadt, R., editors, 30th

USENIX Security Symposium, USENIX Security 2021,

August 11-13, 2021, pages 1235–1252. USENIX As-

sociation.

Kinsman, L., Rotter, T., James, E., Snow, P., and Willis, J.

(2010). Wishful thinking and IT threat avoidance: An

extension to the technology threat avoidance theory.

BMC Medicine, 8(31):552–567.

Kuderli, U. and Neher, L. (2020). Cybersecurity risks – a

matter for the board. PWC Spotlight 15, Price Water

House. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-

risks-report-2020.

Nutbeam, D. (1998). Health promotion glossary. Health

Promotion International, 13(4):349–364.

Ponsard, C., Grandclaudon, J., and Bal, S. (2019). Survey

and lessons learned on raising sme awareness about

cybersecurity. ICISSP, pages 558–563.

Prochaska, J. and DiClemente, O. (2005). The transtheo-

retical approach. J. C. Norcross & M. R. Goldfried

(Eds.), Oxford series in clinical psychology. Hand-

book of psychotherapy integration (p. 147–171). Ox-

ford University Press.

Pugnetti, C. and Casi

´

an, C. (2021). Cyber risks

and swiss smes: an investigation of em-

ployee attitudes and behavioral vulnerabilities.

https://digitalcollection.zhaw.ch/handle/11475/21478.

Team, C. (2021). The urgent need to strengthen the cyber

readiness of small and medium-sized businesses.

https://cyberreadinessinstitute.org/the-urgent-need-

to-strengthen-the-cyber-readiness-of-small-and-

medium-sized-businesses-a-global-perspective.

Tuladhar, A., Lende, D., Ligatti, J., and Ou, X. (2021). An

analysis of the role of situated learning in starting a

security culture in a software company. In Chiasson,

S., editor, Seventeenth Symposium on Usable Privacy

and Security, SOUPS 2021, August 8-10, 2021, pages

617–632. USENIX Association.

Weir, C., Blair, L., Becker, I., Sasse, M. A., and Noble,

J. (2018). Light-touch interventions to improve soft-

ware development security. In 2018 IEEE Cyberse-

curity Development, SecDev 2018, Cambridge, MA,

USA, September 30 - October 2, 2018, pages 85–93.

IEEE Computer Society.

Zec, M. (2015). Cyber security measures in SME’s: a

study of it professionals’ organizational cyber security

awareness. Linnaeus University, Kalmar. Zugriff unter

http://www. divaportal. org/smash/get/diva2, 849211.

ICISSP 2023 - 9th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

388