The Influence of Gender on Students' Perception of Risk in Portugal

Bruno Martins

1

a

and Adélia Nunes

2

b

1

Department of Geography and Tourism, CEGOT (Centre of Studies on Geography and Spatial Planning),

University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

2

Department of Geography and Tourism, CEGOT (Centre of Studies on Geography and Spatial Planning),

University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Keywords: Risk Perception; Students; Gender; Education; Portugal.

Abstract: This study analyses the perception that students at the end of the 3rd cycle, in Portugal, have of a set of natural

and environmental risks, considering their manifestation both nationally and in the area of residence. It also

sets out to understand how students perceive the risks, taking into account the causes, the future trend, and

support from public authorities, as well as the willingness to change attitudes regarding risk mitigation and

reduction. The results suggest that students have a relatively low-moderate perception of risk. The risks of

forest fires, heat waves, air and water pollution, and flooding are the ones they single out as most likely to

occur, mainly as a consequence of climate change. Gender proved to be an important variable in perception,

particularly in terms of manifestation and personal perception of risk. These results can influence the strategies

and resources to be applied in the educational context, so that there is less reason to educate the youngest

children about the need to prevent risk, and to reduce the impact of disasters and strengthen the resilience of

the community in general.

1 INTRODUCTION

Understanding how the general public perceive

natural and environmental risks is crucial for a better

definition of communication and information

strategies on risks. However, it can lead to more

efficient risk management strategies, which will

somehow contribute to societies that are better able to

respond in crisis situations and that have greater

social resilience.

Research on risk perception depends on various

local/geographic and personal factors, including: the

location of the individual (Bera & Danek, 2018);

housing characteristics (Hung, 2009; Thistlethwaite

et al, 2018); the consequences of the risk

manifestation (Stojanov et al.; 2015); the impacts of

the crisis (Thistlethwaite et al, 2018); the socio-

economic and demographic profile (such as age,

education, gender, income) (Balog-Way et al.., 2020);

direct experience (Terpstra, 2009; Bera & Danek,

2018); race (Macias, 2016); the historical-cultural

context (Armas et al., 2015); and the political and

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8681-2349

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8665-4459

religious context (Bichard & Kazmierczak, 2012). Of

the multiple variables that can influence risk

perception, the gender difference has been described

in several studies as a relevant factor, noting that

women have higher levels of risk perception and

show greater concern than men (Lindell & Hwang,

2008; Poortinga et al. 2011; Martins et al., 2019).

However, other studies (Bradford et al., 2012) have

not reported a robust correlation between risk

perception and gender.

Education, particularly school, does seem to play

a very important role in risk reduction, however. In

general, individuals with a higher level of education

tend to develop more accurate levels of risk

perception, generally adopting more effective

preventive behaviours towards risk (Striessnig et al.,

2013; Muttarak & Lutz, 2014).

Based on the application of questionnaires to

students living in several regions of Portugal, we set

out to assess how students at the end of the 3rd cycle

of basic education, perceive: (i) the probability of

manifestation of natural and environmental risks,

taking into account a number of natural and

Martins, B. and Nunes, A.

The Influence of Gender on Studentsâ

˘

A

´

Z Perception of Risk in Portugal.

DOI: 10.5220/0011921500003536

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment (ISWEE 2022), pages 111-116

ISBN: 978-989-758-639-2; ISSN: 2975-9439

Copyright

c

2023 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. Under CC license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

111

environmental hazards affecting the national territory

and their area of residence; (ii) the triggering factors;

(iii) the support of public authorities in the event of

crisis; (iv) the future trends regarding their

manifestation; (v) and the willingness to change their

attitude regarding the mitigation and reduction of the

respective impacts. The issue as to whether students

of different gender have different perceptions on the

previous questions is also examined.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Background to the Study Area

Mainland Portugal is located in southwestern Europe,

between latitude 36º57' N and 42º9' N, and longitude

6º 12' W and 9º 30' W. It occupies approximately

92,212 km

2

and has 10.3 million inhabitants. The

insular part corresponds to the archipelagos of

Madeira and Azores, located in the Atlantic Ocean.

Several risks affect the mainland territory. In the

North and Centre regions of Portugal the risk of forest

fires is dominant, less so in the south, with the

exception of the Algarve mountains. In the south,

drought and desertification are the most important

risks, especially in eastern Alentejo. The risk of

flooding is greater in the lower, estuarine, courses of

the main Portuguese rivers, especially in the North

and Centre regions, as is the case of the Douro, Vouga

and Mondego rivers, and, further south, the Tagus.

2.2 Questionnaire and Statistical

Analysis

In order to assess the perception that end-of-school

students have regarding a set of natural and

environmental risks, a survey questionnaire was

applied to 376 students living in mainland Portugal.

The average age of the respondents is 15 years old;

about 47% were female and 53% male.

The questionnaire is structured in six parts. In the

first part ‘respondents are characterised’ and in the

second part students are asked to ‘Rank the risks

according to the probability of their occurrence’, at

national and municipal level. Fifteen natural and

environmental risks were listed and a qualitative

Likert scale was used to rank them, ranging from 1 -

nil/minimum; 2 - low; 3 - moderate; 4 - high; 5 -

maximum. The lowest value (nil or minimum) is

therefore linked to a very low risk perception in

relation to the probability of occurrence of the risk, as

opposed to the highest value (maximum), correlated

with a very high probability of manifestation.

The third part of the questionnaire considers

questions aimed at analysing the respondents’

perception of risk, such as: (i) whether risks tend to

increase in the future; (ii) whether they arouse fear;

(iii) whether individual actions influence risk; (iv)

whether they are concerned about the consequences

of risks; (v) whether they are willing to change

individual behaviour. The fourth part is aimed at

analysing the understanding of causes. This part of

the questionnaire considered: (i) whether risks result

from anthropic action; (ii) whether they result from

climate change; (iii) whether they result from poor

planning and land use planning; (iv) whether they

result from divine punishment; (v) whether they are

unpredictable natural events. The fifth part,

‘Channels of information on risk’, was intended to

examine the means of communication considered

most effective in communicating and informing about

risks, considering the role of education, the media and

the Internet. Finally, the sixth part of the

questionnaire looked at students' perceptions of state

support in the event of a crisis.

To assess whether there are statistically

significant differences between female and male

students in the different components of risk

perception, the independent t-test was used to

compare the mean difference between genders.

3 RESULTS

In general, the perception of the risks considered

according to their manifestation is low to moderate,

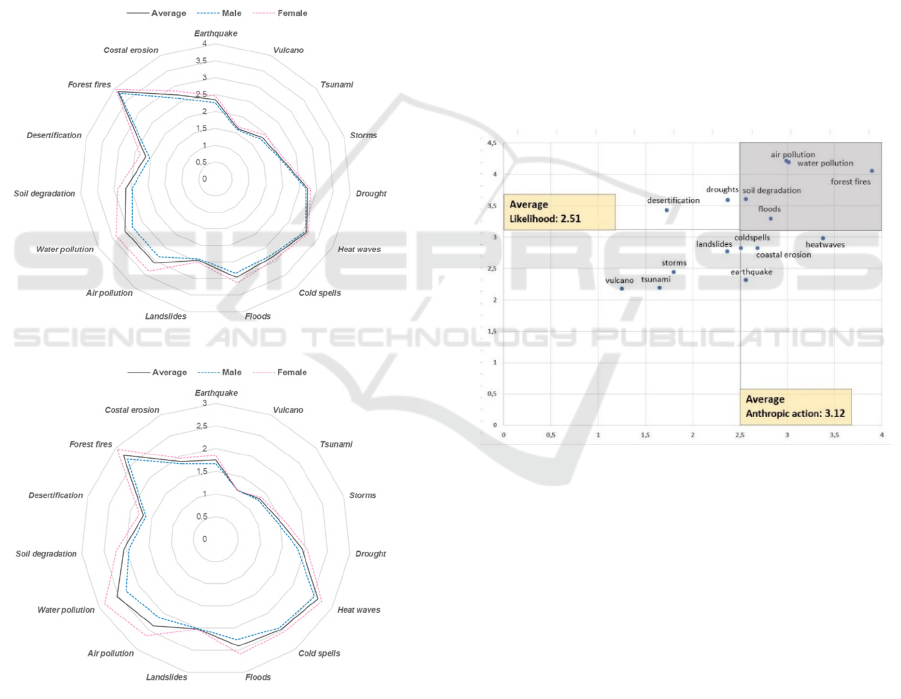

mainly at the local scale (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Distribution of the relative frequencies (%) by

class, according to the occurrence of different risks at

national level (A) and Madeira (B).

ISWEE 2022 - International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment

112

The risks with the highest perception values are

forest fires (average 3.87) and heat waves (average

3.12). These are followed by water pollution (average

3.08), air pollution (average 3.06) and coastal erosion

(average 2.72). The lowest values of risk perception

were the geophysical risks, in particular the risk of

volcanism (average 1.63) and tsunami (average 1.85),

based on the national scale.

With regard to the area of residence, the risks with

the highest perception are forest fires (average 2.77),

water pollution (average 2.53), cold spells (average

2.46), and floods (average 2.41). With lower

perception we find the volcanic risk (average 1.18),

tsunamis (average 1.32), storms (average 1.46), and

desertification (average 1.70).

A

B

Figure 2: Overall risk rating (mean) for females and males

(A National level, B Municipal) (Likert scale: 1 -

nil/minimum; 2 - low; 3 - moderate; 4 - high; 5 - maximum).

The results indicate statistically significant

differences (Levene’s test for equality of variances/ t-

test for equality of means) in the perception of risks,

taking gender into account. This fact is seen more

clearly at the local scale, and for the risks of flooding

(sig. 0.005), water (sig. 0.000) and air pollution (sig.

0.000), desertification (sig. 0.009), and soil

degradation (sig. 0.009). Female students have a

higher perception of risks than male students,

particularly when it comes to the risk of air and water

pollution, floods, forest fires and coastal erosion.

(Fig. 2).

Most students understand that the considered

risks, especially forest fires, tsunamis, storms and

earthquakes, can cause material and human losses.

Similarly, they consider that the occurrence of the

risks will tend to increase in the future, especially the

risks of air and water pollution, forest fires, and heat

waves.

The results also very clearly suggest the

importance of anthropic action as a risk amplifying

factor, especially regarding the risk of water (mean

4.16; n=162) and air pollution (mean 4.18), and the

risk of forest fire (mean 4.04) (fig. 3).

Figure 3: Comparing perceptions on likelihood and

anthropic action as a risk-increasing factor.

Climate change is seen as a cause of increased risk of

heat waves (mean 4.09), droughts (mean 4.02), cold

spells (mean 3.83) and forest fires (mean 3.76). Once

again, gender establishes statistically significant

correlations with the fear of risks (sig. 0.000), with

individual actions as a risk-influencing factor (sig.

0.004), with the concern about risks (sig. 0.000), and

with behavioural change (0.003) towards risk

mitigation (Table 1). It is the female students who are

more concerned about the consequences of the

manifestation of risks; they are more afraid and

believe that individual action contributes

significantly to risk reduction. They also tend to

ascribe the causes of an increase in the occurrence of

disasters to poor land use planning policies and are

The Influence of Gender on Studentsâ

˘

A

´

Z Perception of Risk in Portugal

113

more willing to change their behaviour in order to

moderate the impacts of risk manifestation.

Table 1: Levene’s and t-test for risk perception.

Note: Asterisk, significant relationships between groups (p-value <

0.05); n= 376.

Regarding channels of communication and

information on risks, the students surveyed believe

that the Internet and school are effective channels of

communication. Most students assigned a very

important role to education and the media as vectors

of communication (mean 4.19) and information

(mean 4.07) about risks. However, the Internet is the

most effective vehicle in the process of

communication and information about risks (average

4.07).

In crisis situations, students feel supported by

government bodies.

4 DISCUSSION

School education is very important in risk perception,

serving not only to increase knowledge of the

different potentially dangerous physical processes,

but also to raise awareness of practices aimed at

improving safety. In this study, the students'

perception of the risks considered is low to moderate,

both at national level and, more especially, in the

municipalities where respondents live. These results

corroborate some works that suggest a lower

perception of risk in the municipalities of residence

than at the national scale (Martins et al., 2019; Nunes

& Martins, 2019). This perception seems to be related

to direct experience with crisis situations (Wachinger

et al., 2013) or even to result from the influence of the

media. In fact, the media have proven to be an

important vehicle of information by influencing the

perception very strongly (Biernacki et al., 2009).

News of disasters elsewhere thus seems to influence

perceptions, suggesting that risk events tend to occur

outside the area of residence. However, the greater

attention given to a certain risk is responsible for

creating an indirect experience that influences

perception and that can, in some way, explain the

valuation of a certain risk (in the Portuguese instance,

forest fires) compared to other risks (Siegrist &

Gutscher, 2005).

In general, risks are perceived as potentially

dangerous because they can lead to loss of life and

damage to property. Forest fires and tsunamis are

prominent in this group. Disasters are also seen as

phenomena that will tend to increase in the future,

especially those related to water and air pollution, and

meteorological risks, such as heat waves and cold

spells. In fact, there are several works that point to

atmospheric risks as having the highest perceived

tendency to increase in the future (Garschagen et al.

2020), especially in relation to climate change and

extreme hydrometeorological phenomena (Eck et al.,

2020), and pollution (Altunoğlu et al., 2017).

The results suggest statistically significant

differences with respect to gender. Female students

showed a higher perception than male students,

especially regarding the risk of air and water

pollution, soil degradation and coastal erosion risks,

both at national level and in the municipality where

they lived. These results are in line with some works

that identify gender as a factor in risk perception

(Lindell & Hwang, 2008; Poortinga et al. 2011).

Female students tend to value the consequences of

disasters, too, raising more fear in them. This result is

similar to other studies that suggest that women feel

more fear and concern about the consequences of risk

manifestation than men (Lujala et al., 2015). They

also tend to give greater consideration to their actions

in influencing risk, and are more willing to change

their behaviours to lessen the likelihood that

catastrophic events might occur.

Regarding causes, climate change stands out as

the most important factor in increasing risk. The

strong media coverage of the topic and its relationship

with some risks, particularly those associated with

hydroclimatic extremes, could justify this perception,

in line with several studies that indicate identical

results (Wamsler et al., 2012; Muttarak & Lutz,

2014).

Although education, especially the role of school,

is seen as an important means of information and

communication vis-à-vis knowledge of the physical

phenomena associated with the different risks, social

communication is also emphasized, thus validating

some works that reach the same conclusions

(Biernacki et al., 2009). However, the internet is the

most effective form of knowledge (Roth &

Brönnimann, 2013). Nevertheless, although the

internet contributes very effectively to a wider

Levene's

test for equality

of variances

t-test for equality

of means

Sig. Sig. (2extremities)

I'm worried about the risks* 0.130 0.000

Willing to change* 0.667 0.000

Divine punishment 0.103 0.186

Nature's revenge 0.104 0.178

Planning Policies 0.868 0.177

My actions can lessen the risk* 0.465 0.006

ISWEE 2022 - International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment

114

dissemination of information, this does not mean that

it contributes to greater technical knowledge

(Krimsky, 2007).

The results also suggest that the causes of

occurrence, and the severity of the risks are related to

poor land use planning policies. They also suggest

that individual actions influence the risk, often

aggravating it, and claim that female students are

especially willing to change behaviours so as to

mitigate risks. Several studies (Zaalberg et al., 2009;

Terpstra, 2011) have similarly demonstrated a

positive relationship between emotional elements

such as fear or worry and willingness to implement

measures aimed at mitigating the impacts of risk

occurrence.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Risk perception is inherently personal and subjective,

and results from a combination of knowledge and

judgment associated with social, psychological,

cultural and political factors. Given this multiplicity

of factors, the analysis in this study is somewhat

limited and focuses mainly on gender and the socio-

cultural background of the students surveyed.

Gender, indeed, proved to be a variable with

significant influence on perception, particularly in

terms of personal risk perception. Female students

were more concerned about risks, as they are more

afraid because they think that risks will be more

frequent in the future and have increasingly

significant impacts. Female students also have a

higher perception of risk depending on its

manifestation. However, further work is needed in

order to consolidate this conclusion by including

more variables.

In fact, in Portugal the subject ‘Risks and

Disasters’ has only recently been introduced in the

school curriculum. Therefore, there are still no studies

on the contribution of this content to the perception of

risk by students. Thus, it is essential to carry out

studies, with a larger sample and over a longer period

of time, aiming at acquiring sounder knowledge about

how education, and school in particular, influences

students' risk perception. It will then be possible to

benefit equally from a more correct approach to

teaching methods and from the quality of educational

materials and resources used in the teaching-learning

process, thereby deepening knowledge and raising

students' awareness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research received support from the Centre of

Studies in Geography and Spatial Planning

(CEGOT), funded by national funds through the

Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under

the reference UIDB/04084/2020.

REFERENCES

Altunoğlu, B., Atav, E., Sönmez, S., 2017. The

Investigation of Environmental Risk Perception and

Attitudes Towards the Environment in Secondary

School Students, The Turkish Online Journal of

Educational Technology, pp. 446-477.

Armas, I., Ionescu, R., Posner, C.N., 2015. Flood risk

perception along the Lower Danube river, Romania.

Nat Hazards (79), 1913-1931.

Balog-Way, D., McComas, K. and Besley, J., 2020. The

Evolving Field of Risk Communication. Risk Analysis

(40), 2240-2262. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13615

Bera, M. and Danek, P., 2018. The perception of risk in the

flood-prone area: a case study from the Czech

municipality. Disaster Prev Manag 27, (1), 2-14.

Bichard, E. and Kazmierczak, A., 2012. Are homeowners

willing to adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate

change? Clim Chang (112), 633-654.

Biernacki, W., Działek, J., Janas, K., Padło, T., 2008.

Community attitudes towards extreme phenomena

relative to place of residence and previous experience.

In Liszewski S (ed). The influence of extreme

phenomena on the natural environment and human

living conditions (pp. 207-237).

Bradford, R., O'Sullivan, J., van der Craats, I., Krywkow,

J.; Rotko, P., Aaltonen, J., Bonaiuto, M., De Dominicis,

S., Waylen, K., Schelfaut, K. 2012. Risk perception-

Issues for flood management in Europe. Nat. Hazards

Earth Syst. Sci., 12, 2299-2309. doi:10.5194/nhess-12-

2299-2012.

Eck, Christel & Mulder, Bob & van der Linden, Sander

2020. Climate Change Risk Perceptions of Audiences

in the Climate Change Blogosphere. Sustainability. 12.

7990. 10.3390/su12197990.

Garschagen, M., Wood, S. L. R., Garard, J., Ivanova, M., &

Luers, A., 2020. Too big to ignore: Global risk

perception gaps between scientists and business

leaders. Earth's Future, 8, e2020EF001498.

https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EF001498

Hung, H., 2009. The attitude towards flood insurance

purchase when respondents' preferences are uncertain:

a fuzzy approach. J Risk Res 12(2):239-258

Krimsky, S. 2007. Risk communication in the internet age:

The rise of disorganized skepticism, Volume 7, Issue 2,

p.157-164.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envhaz.2007.05.006

Lindell, K., Hwang, S., 2008. 'Households' perceived

personal risk and responses in a multi-hazard

The Influence of Gender on Studentsâ

˘

A

´

Z Perception of Risk in Portugal

115

environment', Risk Anal. 28 (2), 539-556,

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01032.x.

Lujala, P., Lein, H., Rød, J., 2015. Climate change, natural

hazards, and risk perception: the role of proximity and

personal experience, Local Environ. 20 (4), 489-509,

https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.887666.

Macias, T., 2016. Environmental risk perception among

race and ethnic groups in the United States. Ethnicities,

Vol. 16 (1) 111-129,

https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796815575382

Martins, B., Nunes, A., Lourenço, L., Castro, F., 2019.

Flash Flood Risk Perception by the Population of

Mindelo, S. Vicente (Cape Verde), Water, Volume 11,

Issue 9, p.15. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091895

Muttarak, R. and Lutz, W., 2014. Is education a key to

reducing vulnerability to natural disasters and hence

unavoidable climate change? Ecology and Society

19(1): 42. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-06476-190142

Nunes, A. & Martins, B. 2019. Exploring the spatial

perception of risk in Portugal by students of Geography,

Journal of Geography, vol.119, Issue 5

https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2020.1801803

Poortinga, W., Spence, A., Whitmarsh, L., Capstick, S.,

Nick F. Pidgeon,N. F., 2011. Uncertain climate: An

investigation into public scepticism about

anthropogenic climate change, Global Environmental

Change, 21(3), 1015-1024,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.03.001.

Roth, Florian and Brönnimann, Gabriel, 2013. Using the

Internet for Public Risk Communication. Risk and

Resilience Reports.

Siegrist, M., Gutscher, H., Earle, T. C., 2005. Perception of

risk: The influence of general trust, and general

confidence. Journal of Risk Research, 8(2), 145-156.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1366987032000105315

Stojanov, R., Duz, B., Danek, T., Nemec, D., Prochàzka,

D., 2015. Adaptation to the impacts of climate extremes

in central Europe: a case study in a rural area in the

Czech Republic. Sustain 7(9):12758-12786

Striessnig, E., W. Lutz, and Patt, A., 2013. Effects of

educational attainment on climate risk vulnerability.

Ecology and Society 18(1): 16.

http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-05252-180116

Terpstra, T., 2009. Flood preparedness: thoughts, feelings

and intentions of the Dutch public. Thesis, University

of Twente, Twente.

Thistlethwaite, J., Henstra, D., Brown, C., Scott, D., 2018.

How flood experience and risk perception influences

protective actions and behaviours among Canadian

homeowners. Environ Manag (61),197-208

Wachinger, G., Renn, O., Begg, C., Kuhlicke, C. 2013. The

Risk Perception Paradox - Implications for Governance

and Communication of Natural Hazards. Risk Analysis,

(33), 1049-1065.

Wamsler, C., Brink, E., Rentala, O., 2012. Climate change,

adaptation, and formal education: the role of schooling

for increasing societies' adaptive capacities in El

Salvador and Bazil. Ecology and Society 17(2):

2.http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04645-170202

Zaalberg, R., Midden, C., Meijnders, A., McCalley, T.,

2009. Prevention, adaptation, and threat denial:

flooding experiences in the Netherlands. Risk Anal

(29),1759-1778

ISWEE 2022 - International Symposium on Water, Ecology and Environment

116