User Empowering Design: Expanding the Users' Hierarchy of Needs

David Gallula

1a

, Hadar Ronen

2

, Ido Shichel

3

and Adi Katz

4b

1

Department of Information Systems, The Yezreel Valley Academic College, Israel

2

Department of Education and Society, Ono Academic College, Israel

3

Department of Learning Disabilities, University of Haifa, Israel

4

Usability Center, Industrial Engineering and Management Department, SCE, Ashdod, Israel

Keywords: User Empowerment, User Empowering Design, User-Centred Design, Usability, User Experience,

Human Computer Interaction.

Abstract: We offer a comprehensive framework for HCI designers to empower users. Our purpose is to lay the

foundations for a complete design method: User Empowering Design (UED). Empowerment is not a new

human need, and the ability of technologies to empower users has already been discussed and deemed

important by many experts. UED concentrates on the human need to fulfil the potential for growth, increase

strengths, and reduce weaknesses. It does not replace user-centred design (UCD) but expands it to a higher-

level need. Thus, we suggest that UED is the third revolution in developing interactive technology. Just as

user experience (UX) has expanded usability, UED expands the user experience. The UX design method

focuses on the user experiences while interacting with a digital product (e.g., emotions, feelings, aesthetics,

hedonic needs). The UED approach takes a step further, as it focuses on the impact that goes beyond the scope

of the digital product with an emphasis on aspects that are in the user's main life path. Within this framework,

we offer a methodology that includes eight distinct models, each referring to a variety of technologies that

have an impact on personal, community and organisational empowerment. We explain the current need for a

design that is intended to empower users, present the different models by describing their mechanisms, and

offer practical examples to implement the empowering design.

1

INTRODUCTION

Technological advancement in recent decades has led

to fundamental changes in the way users think about

and use their digital products. Today, users are no

longer settling for a merely functional product, or for

having a pleasant experience when using the product.

It seems that as technology progresses, users also

expect more from their digital products. In this paper,

we argue that product designers should address an

additional need, which is at a higher level than user

experience. Therefore, we call for User Empowering

Design (hereafter UED). In his seminal paper,

Shneiderman (1990) declared that users need to be

empowered by technology and stated that they should

“be able to apply their knowledge and experience to

make judgments that lead to improved job

performance and greater personal satisfaction.” The

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7065-2819

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8143-709X

term “Empowerment” denotes reinforcing and

enabling people so that they realize their abilities,

increase their strengths, have a high level of belief in

themselves, and perceive themselves as more self-

efficient (Brendtro et al., 2002). Our research follows

the idea that there should be design methods that

intentionally achieve user empowerment (Gallula and

Frank, 2014) and aims to encourage innovative ideas

and tools for empowering users with technologies.

In recent years, we have witnessed a rise of the

concept of empowerment in various fields, such as

employment and learning. In the field of employment,

one of the most prominent factors that impact

employees’ engagement, their commitment to the

organisation, and their level of performance at work,

is employee empowerment (Osborne and Hammoud,

2017; Hanaysha, 2016). In the past, work was

regarded as a source of livelihood and financial

security. Later generations sought interest and self-

Gallula, D., Ronen, H., Shichel, I. and Katz, A.

User Empowering Design: Expanding the Users’ Hierarchy of Needs.

DOI: 10.5220/0011552500003323

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications (CHIRA 2022), pages 201-208

ISBN: 978-989-758-609-5; ISSN: 2184-3244

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All r ights reserved

201

satisfaction in the workplace (including a good

atmosphere, and fascinating tasks). Nowadays,

people are looking for a workplace that allows them

to develop abilities and skills, grow and feel

empowered. In a similar vein, in the field of learning,

the rhetoric of empowerment has been linked to

formal education (Selwyn, 2011). This is evident in

the literature related to learning technologies and

pedagogic approaches, where the Internet is

considered an appropriate space for autonomous

learning and where students can exercise their power

and experience with a high degree of freedom and

control (see, e.g., Prinsloo and Slade, 2017; Bennett

and Folley, 2019).

In this paper, we will address the manner in which

digital products can provide empowerment to their

users. We begin by describing the user empowerment

framework, followed by a discussion of the applied

implications of the model, and conclude with

recommendations for future research. Before we

broaden the scope of user empowerment and discuss

how it can be applied in practice in designing digital

products, we must first understand the building

blocks on which user empowerment is laid, i.e., the

current designers’ focus on user's interaction with

digital products and determine whether existing

trends fulfil the aim of user empowerment.

1.1 Time to Address a Higher Order of

User Needs

According to the User-Centred Design (hereafter

UCD) approach, the purpose of a system is to serve

its users, and the needs of the users should lead the

design of the system’s interface (Norman, 1986).

Currently, the UCD approach concentrates on two

main design methods that meet the users’ needs:

Usability and User Experience (UX). Usability

emphasizes the effectiveness, efficiency, and

satisfaction of execution (Nielsen, 1993) and UX

emphasizes the feelings, sensations, and experiences

of a user (Norman, 2004).

The UED framework is inspired by the ERG

(existence, relatedness, growth) theory (Alderfer,

1969). This refers to an order of needs, in which

certain needs serve as building blocks for higher

needs. If we relate to Alderfer’s theory, existence is

the basic material required for living and is the

cornerstone of the hierarchy pyramid; relatedness

emphasizes the importance of social interactions and

positive emotions, and growth describes the urge to

continue personal development and therefore is at the

top of the pyramid. We propose an extension to the

UCD model by adding a third and higher level to the

users’ needs hierarchy. We claim that it is time to

consciously add user empowerment when designing

digital products.

1.1.1 Usability: The First Need

Usability addresses the users’ need to perform well in

tasks and successfully complete the tasks conducted

via the interfaces of digital systems (Nielsen, 1993).

It refers to the extent to which a system, product, or

service “can be used by specified users to achieve

specific goals with effectiveness, efficiency (in

minimum time, with minimum errors), and

satisfaction in a specified context of use” (Bevan et

al., 2015; ISO FDIS 9241-210). Nielsen referred to

usability as a method for improving ease of use during

the design process. The usability emphasizes the

user's need to achieve pragmatic goals such as

successful and efficient performance in tasks

supported by the computerized system, with a focus

on cognitive and task-oriented aspects, emphasizing

the instrumental value of technological products

(Hassenzahl and Tractinsky, 2006).

1.1.2 User Experience: The Second Need

A User Experience (UX) goes beyond meeting the

instrumental (pragmatic) user's needs for usefulness,

efficiency, and satisfaction. It strives to optimize the

user's holistic experience, which includes the need to

achieve hedonistic goals (Hassenzahl and Tractinsky,

2006). Among these goals, users require aesthetic

pleasure, fun, being surprised, and entertainment

(Gaver and Martin, 2000). The holistic UX includes

emotions, beliefs, preferences, psychological

responses, and physical behaviours (Bevan, 2009).

1.1.3 Empowerment: The Third Need

Shneiderman (1990) declared that users need to be

empowered by technology. Kim and Gupta (2014)

demonstrated the critical role of user empowerment

in regulating IS infusion in organizations. Schneider

et al. (2018) claim that empowering people through

technology is of increasing concern in the HCI

community and reviewed 54 CHI full papers using

the terms empower and empowerment. Inspired by

these previous works, we too concentrate on the

human need to be empowered.

1.1.4 User Empowering Design (UED)

User empowering design (UED) goes a long way

beyond the concept of UX. While UX strives to

increase feelings and emotions of pleasure and

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

202

enjoyment, these remain within the limited context of

interacting with the product or system. In contrast,

UED focuses on the effects of the interaction beyond

its occurrence, not in limited terms of reflection on

the user experience, but in a way that benefits aspects

of the user's life that are outside and beyond the

product’s use experience. UED is a powerful idea,

because it is based on the understanding that

technological product designers can positively impact

the users' well-being. UED strives to strengthen the

users and minimize their weaknesses, which are

reflected in the central path of their life. Therefore, it

significantly expands the ramifications that a product,

system, or service has for its user by fulfilling the

user’s need to be empowered in their personal life.

We define UED as a method built from a

collection of design rules and principles aiming to

design HCI systems that meet the need for user

empowerment. These systems will have positive

effects on the perceptions or abilities that are in the

main path of the user's life, in a way that minimizes

the user's weaknesses and/or emphasizes the user's

strengths. While it is possible that the existing models

for designing user-technology interaction might

provide user empowerment unintentionally as a most

welcome side effect, there is more to aspire to. We

argue that the existing situation in HCI should not be

left intact, and the growing need for empowerment

must be addressed; The fact that there is currently no

orderly design method that consciously provides an

answer for this need motivated us to explore and offer

a preliminary basis for such a method. As the

previous two methods have evolved over decades of

research and practice, we do not claim to offer in this

paper a complete and encompassing method, but only

raise awareness of this need and suggest

implementation options.

Just as the need for good UX has not replaced the

need for usability, so the need for empowerment will

not replace the two previous needs. An empowering

product should also be usable and provide a good UX.

Different user need should not come at the expense of

each other. However, different products may

emphasize a particular need, according to their

purpose and the context of their use.

1.1.5 Why Now?

To this date, there is no orderly method designed to

empower users. We believe that the conditions for

empowering users have matured, and this is the time

for a qualitative leap towards a design that is

consciously dedicated to user empowerment. This

argument is based on four components:

First, it is the Zeitgeist of the current generation

who grew up with technology, which leads its users

to take functionality for granted, cease to be satisfied

with positive experiences, and expect technology to

improve their lives. As in the other areas of life we

mentioned earlier - work and education - expectations

from technology are undergoing a revolution.

Usability and UX are already considered foundational

and the need for a transition to the next level has

arisen.

The second factor is technological maturity.

Nowadays, the hybridity and friction between

humans and technology (e.g., mobile and wearable

devices, augmented reality, virtual reality, IoT) create

a symbiosis between users and the technological

products that surround them. Advanced digital

developments such as Metaverse will increase this

friction. New digital products will continue to adjust

and adapt themselves to the user (e.g., by using AI

and machine learning). While these technological

developments integrate and keep the users more and

more inside the digital matrix, the concept of user

empowerment emphasizes positive changes in the

users' well-being outside the virtual space.

The third factor is based on the fact that, at

present, steadiness, in terms of not regenerating

products, is detrimental to digital companies, and

therefore there is a constant demand for continuous

innovation. Big tech companies that have reached

maturity and technological extraction are seeking

their next breakthrough. Having a competitive

innovation edge is a key aspect of survival and

growth. This makes ‘innovate or perish’ the new

motto of the global knowledge economy era (Shakina

and Barajas, 2020). Thus, one way to overcome

technological barriers and continue to innovate is by

addressing the human high-quality need to be

empowered.

Lastly, Netflix’ “Social Dilemma” documentary,

which came out in 2020, raised public awareness of

the negative sides of social networks, including their

ability to act as an “addictive drug” (see also Eyal,

2014 on the addictive patterns underlying

technologies). We use the term “Junk Tech” (Bally

and Desmaison, 2021) to describe technology as tasty

but not healthy for us users. That is, we consume

digital products in a way that is equivalent to eating

unhealthy fast food. Technological products capture

our attention and without being aware, we fall into the

rabbit hole. This, for example, causes us to stay

awake late at night, and thus affects us negatively the

next day. Usability, user experience, and

empowerment can be analogous to food consumption

influences. Just as consumers have realized that they

User Empowering Design: Expanding the Users’ Hierarchy of Needs

203

can and should demand food that is not only fast and

tasty, but also healthy, so will users of digital products

undergo a transformation and stop settling for just the

experience. They will demand products that will also

improve their well-being, lead them to personal

growth and help them fulfil the important goals in

their lives. In other words, people will look for

products that empower them to manage their well-

being and health (Blandford, 2019; Seshadri et al.,

2019). Illustrative examples are apps for body self-

acceptance to elevate the self-esteem of young people

(Paay et al., 2018), for raising the sense of self-

efficacy among job seekers such as "review me" and

"Interview4" (Dillahunt and Hasiao, 2020), and for

dealing with social anxiety, such as the app

"CogniShift" (Elefsen and Khaliq, 2021).

2

HOW TO IMPLEMENT UED

We propose to expand the UCD theory and add

practical tools that enable user empowerment.

To develop a digital product, one must start from

the premise of the steps within the UCD. Within

them, we will focus on the first two processes of the

UCD - research and concept, as a thorough

examination of the design and test stages are beyond

the scope of the current paper. When developing a

new digital product or updating an existing one, the

designers of the product must keep in mind that the

product can improve the user's strengths, and we

encourage them to think of ways to help the users

reach their potential in the central path of their life.

2.1 Research

We consider the common tool of personas as an

effective UCD method (Cooper, 1999; Jansen et al,

2022; Goodwin, 2011). In UED, the persona's

description (user card) includes additional layers that

describe the importance of the product for the user in

terms of the technological product's potential impact

on the user's life beyond the course of interaction with

the product itself.

The UED approach introduces additional

important aspects to the process of building personas,

including the user's personal potential mapping tool.

Using this tool, we ask about the life of the user and

define their “main path,” i.e. their important goals and

ambitions, strengths and weaknesses in the context of

that main path. Applying our mapping tool, for each

persona we add several Likert-type scales, each

representing an attribute that is relevant to the main

path. The attributes are important characteristics or

abilities that the persona wants to have or fulfil. On

each attribute scale, we mark the persona’s current

state and their potential future state. In addition, we

describe the factors that currently inhibit or prevent

the persona from realizing their potential.

2.2 Concept

We suggest that the product designer employ a

systematic usage of our methodology. After the

designer defines the trait/ability that the user wishes

to emphasize and identifies the factor that inhibits the

user’s potential to advance that trait (the “preventive

factor”) – the methodology systematically leads the

designers through certain paths to the most suitable

design solutions.

The methodology we offer includes eight distinct

models, demonstrated in Table 1. Each model appears

in a separate column and represents a different

“preventive factor.” We suggest a suitable design

solution for each of these factors, which may

empower the user beyond the course of interaction

with the technological product. We divided the

models into two groups: four models see technology

as the solution for dealing with the preventing factor,

and the other four models identify the source of the

preventing factor in the technology itself.

Due to space constraints, we will demonstrate only

two models out of the eight described in Table 1, the

Walls and the Ripples. For each, we suggest design

features specifically intended to empower users using

a popular instant messaging application, WhatsApp.

2.2.1 The Wall Model: Intergenerational

Dictionary

Many adults experience technology as an obstacle in

their lives. Age-related barriers are derived from

normal changes that a person undergoes in cognition

and physical conditions, along with affective barriers

(age-related perceptions and attitudes towards

technology). In addition, technologies are usually not

designed to be age-friendly. The combination of these

factors leads to intergenerational gaps and negative

consequences, including digital exclusion that may,

in turn, lead to social exclusion and deterioration of

the sense of belonging (Katz and Sophia, 2021). The

acquisition of online literacy for digital

communication creates a linguistic gap that

distinguishes generation Y from the baby boomer

generation (Subramaniam and Razak, 2014). The use

of nonstandard language, emojis and new forms of

slang in social networks may lead to

misunderstandings and communication barriers.

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

204

Table 1: The eight model that guides designers to empower users.

Technology offers the solution Technology causes the problem

mental aspects lack of abilities unintentional intentional

motivation

b

arriers transien

t

p

ermanen

t

exclusion side effects to addic

t

to har

m

Engines Breaks Trainers Bridges Walls Ripples Hooks Bad Wolf

Ex

p

lanation

Technology

deals with

lack of

motivation

that prevents

the user from

persevering

and

succeeding

Technology

deals with fears

and changes

thoughts that

hinder the user

from realising

his or her

potential

Technology

offers proper

guidance and

coaching, so

users will be

able overcome

transient

difficulties and

inabilities

Technology

can help

users

overcome a

p

ermanent or

inherent

disability

Technology

was not

designed to fit

the user's

needs, and

therefore

becomes an

obstacle,

excluding

users.

While

technology

solves a

problem, it

may create

others, by

causing

unexpected by-

products such

as loss or

degrade of

ca

p

abilities

Technology

was designed

to addict the

user or

negatively

affects the

user

Technology

was designed

to allow for

evil or is

exploited by

users in

immoral

ways

Desi

g

n

Create a habit

by

encouraging

existing

motivations

and by

sparking

hidden

motivations

Encourage small

successes and

dissolve fears in

a safe

environment

Build a training

process that

will encourage

the user to

succeed

without the

product

Build a tool

that will

provide a

permanent

solution

Consciously

include the

user in the

design process.

Refine and

weaken the by-

product

outcomes

without

impeding the

main product

Neutralize an

addiction or

create an

alternative

positive

conduct

Block the

p

ossibility to

harm and

protect the

users

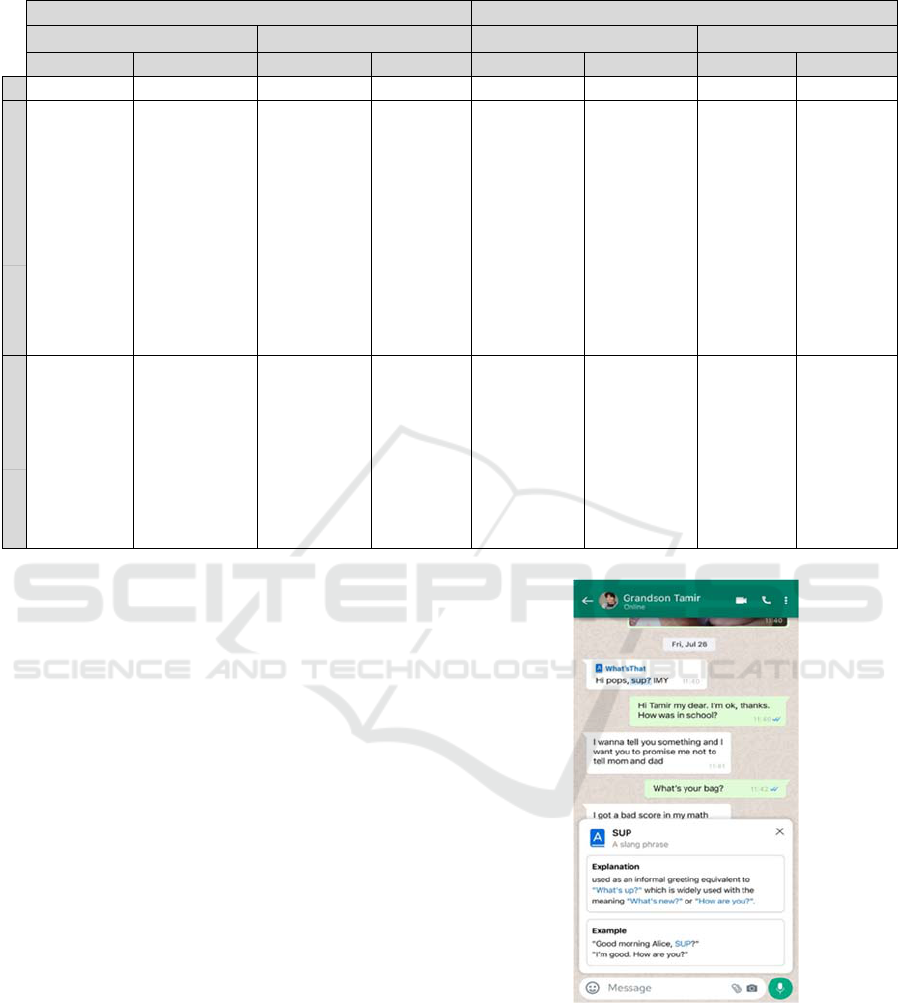

One of the weaknesses of the WhatsApp

application is faulty communication caused by the

user being unfamiliar with unique slang and terms

that are typical to the medium of instant messaging

correspondence. Through the lens of the Walls

Model, Katz and Sophia (2021) identified this

problem and suggested a solution by designing

“WhatsThat,” which provides a synchronous

automatic translation for dialogue participants.

WhatsThat offers a solution that reduces the gap

between participants and minimizes possible negative

consequences for the well-being of all family

members, especially older adults. Figure 1 shows a

screen that demonstrates message exchanges between

Grandpa David and his grandson, Tamir. The figure

presents Grandpa David’s view. Grandpa David

clicked on an embedded link for the word “sup” that

the system generated automatically and received

contextual knowledge (an explanation) retrieved

from the system’s dictionary (Figure 1).

The design contributes to fulfilling the user’s

communication potential with loved family members,

especially grandchildren, by building common

ground, increasing mutual understanding and

overcoming potential miscommunications. This

design focuses on empowering older adults’ self-

efficacy, a meaningful goal that is on the main path of

their lives.

Figure 1: A synchronous automatic” translation” for

dialogue participants.

2.2.2 The Ripples Model: Displaying the

“Important” along with the “Recent”

Nowadays, people make extensive use of instant

messaging applications throughout almost every

waking moment. They constantly check, read, and

User Empowering Design: Expanding the Users’ Hierarchy of Needs

205

send messages in the context of various relationships

and activities: family, friends, work, leisure,

colleagues and more.

The Ripples Model portrays situations in which

technology that was invented to solve a certain

problem inadvertently creates other problems. For

example, nowadays people hardly remember

telephone numbers due to the high availability of

digital personal contact apps. Another example is

navigation apps, which help people efficiently move

from one geographic point to another, freeing them

from the need to remember the directions required to

reach their destination. However, this technological

assistance may come at the cost of the loss of intrinsic

navigational skills and lack of attention to landmarks

situated in a route. Thus, researchers list many

negative side effects and ramifications of

technological designs, including loss of navigational

skills, memory loss, lack of attention, inability to

form interpersonal relationships, loneliness and more

(Amichai-Hamburger and Etgar, 2018; Turkel, 2017;

Goodman, 2021).

For the sake of continuity, we will once again use

WhatsApp to demonstrate another ripple effect. In

order to meet user needs, WhatsApp designers surely

applied the rules of usability and UX. To fulfil users'

needs for efficiently detecting and reading messages,

chats with the most recent incoming messages are

presented at the top of the screen. This design strategy

also reinforces the emotional UX level, since people

become more engaged when seeing a new message.

This emotional response is related to the widespread

Fear Of Missing Out (FOMO), which triggers the need

to be constantly updated. Presenting the most recent

chats at the top supports the immediate need to know

what is happening here and now at any given time.

Although the designers’ good intentions to

provide a user-friendly app that meets the users’ need

for usability and a good experience, WhatsApp’s

current design may impede the need of many users to

preserve and promote certain relations that are

important in their lives. As in various social media

platforms, many users feel that their time and

attention have been hijacked by the abundant social

groups to which they belong and that intensive

involvement in social media negatively affects their

well-being (Sagioglou & Greitemeyer, 2014;

Vorderer et al., 2017; Appel et al., 2020). A mundane

message recently received in the kindergarten

parents’ group finds its way to the top of the chat list.

An inflated volume of chats that find their way to the

top of the screen may push important contacts (such

as family members and dear friends) down the chat

history and thereby lead to the “out of sight – out of

mind” phenomenon. This may blur the distinction

between recent and important, leading users to focus

on recent chats while forgetting about the important

contacts that are out of sight. WhatsApp developers

identified this problem and attempted to offer various

solutions, such as muting groups and allowing users

to pin up to three chats at the top of the chat list.

However, enabling users to pin more than three chats

is not possible. In addition, WhatsApp’s current

design does not create a continuous awareness of the

people that are important to the user. The user's ability

to see their important contacts at any moment is

crucial for the user’s sense of control (Ng, 2004).

We propose a solution that does not require the user

to give up the convenience of having recent messages

appear at the top of the screen. Rather, we focus on

adding a permanent horizontal bar of important contacts

to the top of the screen (see Figure 2). We enable and

encourage users to select and add their important

contacts to the bar that we label "Important to me". This

microcopy will appeal to the user's emotions and act as

a subtle reminder of who is truly important to them. The

ordinary vertical order of chats preserves the recent,

while our new horizontal bar simultaneously pins the

important to the top. Together, the vertical order of

chats and the horizontal bar that we offer allow the user

to find the balance between what happened recently

(changes dynamically) and what is important (relatively

constant), thus restoring their sense of control over the

important things in life. This design will contribute to

the user's main life path outside the product -

maintaining and strengthening the relationships with

the people who are truly important to them.

Figure 2: Fixed bar of important contacts in the upper part

of the screen.

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

206

3 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we lay the foundations for a design

method – UED, motivated by the fact that there is

currently no orderly design method that consciously

provides an answer for empowering users. We

described the user empowerment framework and

explained how it expands UCD to a higher-level user

need. We also described practical solutions that

implement the empowering design. Our framework

offers a methodology that identifies eight models,

each representing a variety of situations that may

have an impact on personal, community and

organisational empowerment.

Empowerment is certainly not a new concept. The

innovation we offer is UED, designing digital

products intentionally to empower users. UED is a

powerful idea, as it emphasises the understanding that

HCI designers can positively affect the users' well-

being and aspects that are in the central path of the

users’ lives (behaviours, worldviews, feelings of self-

worth, self-efficacy and even perceptions of the

meaning of life). While most designers focus on

providing influences that occur during the interaction

(usability and emotions at the time of interacting),

UED is meant to achieve positive effects way beyond

the interaction. We wish not only to highlight this

ability of designers to enhance the impact of their

designs, but also call on designers to take

responsibility for the characteristics of the product

they produce and design products that will better the

lives of their users.

There are already some very interesting and

inspiring projects by Maes in MIT Media Lab that

show how new body-integrated technologies may

assist people by strengthening cognitive skills and

“soft” skills such as attention, learning, decision-

making, creativity, communication, and emotion

regulation. Maes’ works with her students and

colleagues (e.g., Rosello et al., 2016; Leong et al.,

2021) demonstrate how technologies can assist users

in overcoming their limitations and realizing their

goals. Some applications include intelligence

augmentation, memory augmentation, motor

augmentation, augmented decision-making and more.

These works adopt a design approach to create and

study new wearable and immersive systems that can

help people reach a life with well-being, and while

doing so, they are mindful of ethical and social issues.

In future works, we will further expand the

description of the design stages (research, concept,

design and test) under the UED lens. For example, we

will elaborate on practical instructions for building a

persona card that focuses on the user's weaknesses

and strengths. We will also offer design principles for

each of the eight models and include a solution plan

for various problematic situations. In addition, we

will expand the discussion beyond personal

empowerment, to social and organizational

empowerment. To these ends, we will refine the

measures of user empowerment and test the

usefulness of UED by means of empirical

experiments

.

REFERENCES

Alderfer, C. P. (1969). An empirical test of a new theory of

human needs. Organizational behavior and human

performance, 4(2), 142-175.

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Etgar, S. (2018). Internet and

well-being. In The Social Psychology of Living Well

(pp. 298-318). Routledge.

Appel, M., Marker, C., & Gnambs, T. (2020). Are social

media ruining our lives? A review of meta-analytic

evidence. Review of General Psychology, 24(1), 60-74.

Bally, J., Desmaison, X. (2021). Junk tech - how Silicon

Valley won the marketing war. Hermann

Bennett, L., Folley, S. (2019). Four design principles for

learner dashboards that support student agency and

empowerment. Journal of Applied Research in Higher

Education.

Bevan, N. (2009). What is the difference between the

purpose of usability and user experience evaluation

methods? In Proceedings of the Workshop UXEM

2009, Uppsala, Sweden

Bevan, N., Carter, J., Harker, S. (2015, August). ISO 9241-

11 revised: What have we learnt about usability since

1998? In International conference on human-computer

interaction (pp. 143-151). Springer, Cham.

Blandford, A. (2019). HCI for health and wellbeing:

Challenges and opportunities. International Journal of

Human-Computer Studies, 131, 41–51

Brendtro, L., Brokenleg, M. (2002). Reclaiming youth at

risk: Our hope for the future. Solution Tree Press.

Cooper, A. (1999). The inmates are running the asylum.

Indianapolis, IA: SAMS. Macmillan.

Dillahunt, T. R., & Hsiao, J. C. (2020) Positive Feedback

and Self-Reflection: Features to Support Self-efficacy

among Underrepresented Job Seekers. Proceedings of

the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems,(588, 13 pages)

Elefsen, K., Khaliq, A. (2021). CogniShift: Smartphone

Applica-tion for Public Speaking Anxiety. In

Proceedings of Aalborg University (AAU). ACM, New

York, NY, USA, 13 page

Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked: How to build habit-forming

products. Penguin.

Gallula, D., Frank, A. J. (2014, September). User

Empowering Design. In Proceedings of the

2014European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics

(pp. 1-3).

User Empowering Design: Expanding the Users’ Hierarchy of Needs

207

Gaver, B., Martin, H. (2000, April). Alternatives: exploring

information appliances through conceptual design

proposals. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on

Human factors in computing systems (pp. 209-216).

Goodman, M. (2021). Broken attention: How to heal a

world fractured by technology. Kinneret Zmora.

Goodwin, K. (2011). Designing for the digital age: How to

create human-centred products and services. John

Wiley & Sons.

Hanaysha, J. (2016). Examining the effects of employee

empowerment, teamwork, and employee training on

organizational commitment. Procedia-Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 229, 298-306.

Hassenzahl, M., Tractinsky, N. (2006). User experience-a

research agenda. Behavior & information technology,

25(2), 91-97.

Jansen, B. J., Jung, S. G., Nielsen, L., Guan, K. W.,

Salminen, J. (2022). How to create personas: three

persona creation methodologies with Implications for

practical employment. Pacific Asia Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 14(3), 1.

Katz, A., Sophia, Y. (2021). A contextualization feature to

overcome intergenerational language barriers in

communication apps. In Proceedings of the 5th

International Conference on Computer-Human

Interaction Research and Applications - CHIRA (pp.

166-173).

Kim, H. W., Gupta, S. (2014). A user empowerment

approach to information systems infusion. IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, 61(4), 656-

668.

Leong, J., Pataranutaporn, P., Mao, Y., Perteneder, F.,

Hoque, E., Baker, J. M., Maes, P. (2021, May).

Exploring the use of real-time camera filters on

embodiment and creativity. In extended abstracts of the

2021 CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing

Systems (pp. 1-7).

Ng, A. (2004). User friendliness? User empowerment?

How to make a choice? 2004 Spring LIS450IIL

Nielsen, J. (1993). Usability engineering. Morgan

Kaufmann.

Norman, D.A. (1986) User-Centered System Design: New

Perspectives on Human-computer Interaction. In:

Norman, D.A. and Draper, S.W., Eds., Cognitive

Engineering, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale,

31-61.

Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional design: Why we love (or

hate) everyday things. Civitas Books.

Osborne, S., Hammoud, M. S. (2017). Effective employee

engagement in the workplace. International Journal of

Applied Management and Technology, 16(1), 4.

Paay, J., Nielsen,H., Larsen, H. and Kjeldskov, J. (2018).

Happy bits: interactive technologies helping young

adults with low self-esteem. In Proceedings of the 10th

Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

(NordiCHI '18). Association for Computing

Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 584–596.

Prinsloo, P., Slade, S. (2017). Big data, higher education

and learning analytics: Beyond justice, towards an

ethics of care. In Big data and learning analytics in

higher education (pp. 109-124). Springer, Cham.

Rosello, O., Exposito, M., Maes, P. (2016, October).

NeverMind: using augmented reality for memorization.

In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Symposium on User

Interface Software and Technology (pp. 215-216).

Sagioglou, C., & Greitemeyer, T. (2014). Facebook’s

emotional consequences: Why Facebook causes a

decrease in mood and why people still use it. Computers

in Human Behavior, 35, 359-363.

doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.003

Selwyn, N. (2011). Education and technology: key issues

and debates. Continuum International Pub. Group.

Seshadri, P., Joslyn, C., Hynes, M., & Reid, T. (2019).

Compassionate design: Considerations that impact the

users’ dignity, empowerment and sense of security.

Design Science, 5, E21.

Schneider, H., Eiband, M., Ullrich, D., Butz, A. (2018,

April). Empowerment in HCI-A survey and framework.

In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-14).

Shakina, E., Barajas, A. (2020). 'Innovate or Perish?':

Companies under crisis. European Research on

Management and Business Economics, 26(3), 145-154.

Shneiderman, B. (1990). Human values and the future of

technology: A declaration of empowerment. Acm

Sigcas Computers and Society, 20(3), 1-6.

Subramaniam, V., Razak, N. A. (2014). Examining

language usage and patterns in online conversation:

communication gap among generation Y and baby

boomers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together : why we expect more

from technology and less from each other. New York

:Basic Books

Vorderer, P., Hefner, D., Reinecke, L., & Klimmt, C.

(Eds.). (2017). Permanently online, permanently

connected: Living and communicating in a POPC

World. New York, NY: Routledge.

CHIRA 2022 - 6th International Conference on Computer-Human Interaction Research and Applications

208