Towards a Unified Multilingual Ontology for Rhetorical Figures

Yetian Wang

1 a

, Ramona K

¨

uhn

3 b

, Randy Allen Harris

2 c

, Jelena Mitrovi

´

c

3,4 d

and Michael Granitzer

3 e

1

David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Canada

2

Department of English Language and Literature, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Canada

3

Faculty of Computer Science and Mathematics, University of Passau, Innstraße 43, Passau, Germany

4

Institute for Artificial Intelligence Research and Development of Serbia, Fru

ˇ

skogorska 1 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia

Keywords:

Ontology, Rhetorical Figures, Knowledge Representation, Computational Rhetoric, Language Modelling.

Abstract:

Formal ontologies for rhetorical figures have been developed to improve the computational detection for dif-

ferent applications in the area of Natural Language Processing, such as hate speech and fake news detection,

argumentation mining, and sentiment analysis. The existing ontologies all model different aspects of rhetorical

figures, thus creating a variety of formalisms and in the worst case, creating incompatibilities and contradictory

representations. In this paper, we focus on figures of perfect lexical repetition and their representation in three

ontologies in three different languages: The Ploke ontology, the Serbian RetFig, and the German GRhOOT

ontology. We combine those ontologies to benefit from synergy effects and create a multilingual, coherent,

robust, and modular ontology for rhetorical figures of perfect lexical repetition.

1 INTRODUCTION

A rhetorical figure is an extra-grammatical linguis-

tic device which generates attentional effects such as

salience, aesthetic pleasure, and a mnemonic effect at

the receiver side. Rhetorical figures are widespread

in all registers, genres, and dialects of all languages.

There simply does not exist a pure literal language

(Harris et al., 2017). Common rhetorical figures,

such as rhyme and metaphor are encountered in ev-

eryday conversations. One class of rhetorical fig-

ures is called trope, which is characterized by se-

mantics, e.g., a metaphor is the mapping of simili-

tude between semantic domains conveyed. In con-

trast, the class scheme is characterized by the form,

e.g., a rhyme is the repetition of final syllables of

words in a passage. Rhetorical figures have received

more and more attention in the field of Natural Lan-

guage Processing (NLP) in recent years, as their sig-

nificance has become clear for tasks such as argu-

mentation mining (Mitrovi

´

c et al., 2017; Lawrence

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6984-7256

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9750-0305

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9324-1879

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3220-8749

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3566-5507

et al., 2017; Green and Crotts, 2020; Green, 2020),

sentiment analysis (Karp et al., 2021), fake news/hate

speech detection (Musolff, 2015; Caselli et al., 2020;

Lemmens et al., 2021), text summarization (Alli-

heedi and Di Marco, 2014), text improvement (Harris

and DiMarco, 2009), authorship attribution (Strom-

mer, 2011; Java, 2015), machine translation (Clarke,

2019), and translation with focus on maintaining the

rhythm of text (Lagutina et al., 2020). To use rhetor-

ical figures in a computational context, formal mod-

els like ontologies were developed. The goal of the

project RhetFig (Harris et al., 2017; Harris and Di-

Marco, 2009; Kelly et al., 2010) is to build a neuro-

cognitive ontology for rhetorical figures. The ontol-

ogy is ‘neuro-cognitive’ in the sense that it not only

captures ‘isA’ and ‘partOf’ relations among rhetori-

cal figures, it can also infer how a rhetorical figure

generates potential attentional and mnemonic effects,

e.g., whether a word or word group is more salient,

in order to understand rhetorical strategies embed-

ded in an utterance (Harris and DiMarco, 2009; Har-

ris et al., 2017). Rhetorical figure ontologies are re-

quired for automatic figure recognition, annotation,

and generation, which are critical for the aforemen-

tioned tasks. From RhetFig, the RetFig ontology

was developed (note: without the letter “h”) (Mlade-

novi

´

c and Mitrovi

´

c, 2013), an ontology that describes

Wang, Y., Kühn, R., Harris, R., Mitrovi

´

c, J. and Granitzer, M.

Towards a Unified Multilingual Ontology for Rhetorical Figures.

DOI: 10.5220/0011524400003335

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (IC3K 2022) - Volume 2: KEOD, pages 117-127

ISBN: 978-989-758-614-9; ISSN: 2184-3228

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

117

most of the rhetorical figures in the Serbian language.

This ontology was recently translated and adapted to

the German language, modelling 110 German figures,

and named GRhOOT (K

¨

uhn et al., 2022).

The Ploke ontology (Wang et al., 2021) focuses

on modelling the class of rhetorical figures of perfect

lexical repetition, i.e., ploke, from a neuro-cognitive

perspective. It also models how attentional effects are

generated by such rhetorical figures. For example, the

phrase “long long ago”

1

is a figure of perfect lexical

repetition with the word “long” repeated. As stated

by Harris, “[m]ore occurrences of a word increase the

scale of an evoked concept in a constrained range of

ways” (Harris, 2020). Receivers perceive this phrase

with a sense of time that is further away in history

compared to another phrase that simply states “long

ago”. The definition of ‘perfect lexical repetition’ was

adopted from Fahnestock and Harris: “the repetition

of a word or word group with no variation of signans

or signatum” (Fahnestock, 2002; Harris, 2020). In

other words, both the form and meaning of the re-

peated words or word groups stay the same. Thus,

ploke is distinguished from figures of ‘partial lexical

repetition’ such as synonymia, in which synonyms are

used to convey the same meaning, e.g., “How weary,

stale, flat, and unprofitable . . . ” (Shakespeare, Ham-

let, 1.2) (Shakespeare, 2014); polyptoton, in which

words and word groups are repeated with different

morphology, e.g., “ . . . with the remover to remove”

(Shakespeare, Sonnet 116) (Shakespeare, 2014); and

antanaclasis, in which words and word groups are re-

peated with different meanings, e.g., “we must . . . all

hang together, or . . . we shall all hang separately”

(Benjamin Franklin). In this paper, we combine the

figures of perfect lexical repetition of three ontolo-

gies (Ploke, RetFig, GRhOOT) into one multilingual

ontology.

We chose those three ontologies as we want to

focus on multilingual aspects, formal categorization,

and neuro-cognitive affinities. To the best of our

knowledge, the RetFig and GRhOOT ontologies are

the only known non-English ontologies that formally

model rhetorical figures, but they do not include the

effects or purposes of rhetorical figures. However,

GRhOOT already includes multilingualism as it is a

translation and adaption of the Serbian RetFig. We

focus on figures of perfect lexical repetition as they

are extra-grammatical and neuro-cognitively moti-

vated and are therefore language independent. The

Ploke ontology is a perfect choice, as it models fig-

ures of perfect lexical repetition in English and in-

cludes neuro-cognitive aspects. Therefore, the Ploke

1

This is an instance of a figure called epizeuxis, which

we will discuss in Section 3.2.

ontology should be able to incorporate language fea-

tures specific to the Serbian and German ontologies.

Furthermore, all three ontologies aim to be combined

with other ontologies as future work: Therefore, they

were already modelled to allow an extension or adap-

tion. We discuss how the ontologies are fit or unfit to

be connected, and the steps we take to alter any in-

compatible components in the ontologies. However,

each ontology was modelled differently and inconsis-

tencies or deviations are expected. The Ploke ontol-

ogy serves as a baseline since it models the most spe-

cific rhetorical figure concepts among the three on-

tologies.

Our contribution is that we tackle the problem that

many different ontologies for rhetorical figures are de-

veloped that are then incompatible with each other.

Merging rhetorical figure ontologies is a difficult task

due to inconsistencies not only in ontology modelling,

but also in domain-specific knowledge of rhetorical

figures. Therefore, it is critical to understand potential

inconsistencies that may occur when merging them.

By merging the ontologies, they benefit from each

other and synergy effects can be used. We take an-

other step forward to the enhancement of machine-

readable ontologies for rhetorical figures. The re-

sulting ontology is a more robust, tightly-connected

yet modular ontology (or ontological suite), which

demonstrates the re-usability of ontologies. Section

2 summarizes related work on rhetorical figure on-

tologies. Section 3 compares the ontologies, their

rhetorical figures, definitions, and structures. In Sec-

tion 4, we show the differences and inconsistencies

of those ontologies regarding terminology, modelling,

and concepts. A sketch of the combined ontology is

presented in Section 5.

2 RELATED WORK

Fahnestock provides an excellent overview of the de-

velopment of rhetorical figure classification (Fahne-

stock, 2002). As different names and definitions of

rhetorical figures exist, a classification can never be

unambiguous against the background of the inherited

terminology. With the help of ontologies, researchers

have tried to formally model rhetorical figures and

their properties. One of the first ontologies in this

direction models linguistic operations (addition, dele-

tion, etc.) and neuro-cognitive affinities (comparison,

symmetry, etc.), including a formal description of

rhetorical figures and their operations (Harris and Di-

Marco, 2009). The approach is limited to words that

do not have multiple meanings or different forms. The

RhetFig (Rhetorical Figure Ontology) Project (Harris

KEOD 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

118

and DiMarco, 2009; Kelly et al., 2010) has the goal to

build a database, a wiki, and an ontology of rhetorical

figures. Based on this work, an ontology for rhetorical

figures in the Serbian language was modelled in the

Web Ontology Language (OWL) (McGuinness et al.,

2004). This ontology is called RetFig and aims to

model all rhetorical figures in the Serbian language

(Mladenovi

´

c and Mitrovi

´

c, 2013). Another ontology

was developed to spot rhetorical figures of speech in

text (O’Reilly and Paurobally, 2010). The ontology

was modelled using OWL and Semantic Web Rule

Language (SWRL) rules (Horrocks et al., 2004). A

comparison of different forms and rhetorical concepts

shows the context between the Rhetorical Structure

Theory (RST), the Serbian RetFig ontology, and the

Lassoing Rhetoric project (Mitrovi

´

c et al., 2017). An

ontology for the rhetorical figure litotes was modelled

by (Mitrovic et al., 2020).

A top-down, middle-out, and a bottom-up ap-

proach to model an ontology under neuro-cognitive

aspects of rhetorical figures is presented by (Harris

et al., 2017). As future work, the authors would like

to connect their ontology with others, especially “lin-

guistic and cognitive ontologies”. Based on this work,

an OWL ontology for argumentation was developed

for a suite of rhetorical figures (O’Reilly et al., 2018;

Black et al., 2019). The intersection of multiple fig-

ures is considered. The ontology was developed for

a compound rhetorical figure called climax, in which

words or word groups are repeated with a semantic

increase, e.g., “Minutes are hours there, and the hours

are days, / Each day’s a year, and every year an age”

(Suckling, Aglaura, 3.2) (Suckling, 1637). It con-

sists of a trope called incrementum, in which words

or word groups form a semantic increase in a pas-

sage. The figure climax also consists of two rhetorical

figures of perfect lexical repetition, i.e., gradatio and

anadiplosis. An anadiplosis is defined as “the repe-

tition of a word or word sequence on both sides of

a clause or phrase boundary” (Harris and Di Marco,

2017), e.g., “I beg your pardon. Pardon, I beseech

you!” (Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, 4.2) (Shake-

speare, 2014). A gradatio features a sequence of

anadiploses (Harris and Di Marco, 2017). The au-

thors defined anadiplosis and gradatio in terms of el-

ements, colons, and tokens. This model was then

extended to construct the Ploke ontology that cov-

ers other types of rhetorical figures of perfect lexical

repetition and incorporates notions of neuro-cognitive

affinities such as repetition and position (Wang et al.,

2021). By incorporating views from (Harris, 2020),

(Wang et al., 2021) demonstrated that it is possible to

model how simple syntactical patterns such as perfect

lexical repetition can generate attentional effects such

as salience, aesthetic pleasure, and mnemonic effect.

This paper focuses on the future work mentioned

in several papers (Harris et al., 2017; Mladenovi

´

c and

Mitrovi

´

c, 2013; Wang et al., 2021): Combining dif-

ferent rhetorical figure ontologies. We combine the

Ploke ontology with the Serbian RetFig ontology and

its adaption to the German GRhOOT ontology. The

differences between the models will be highlighted

as well as the peculiarities that arise when combining

them into a multilingual ontology. Note that this pa-

per does not focus on ontology matching and merging

techniques since the ontologies and corresponding in-

consistencies involved are particular to the domain of

rhetorical figures. However, procedures discussed in

this paper are inevitably applications of general on-

tology matching and merging techniques. Readers

may refer to (Euzenat and Shvaiko, 2013) for a com-

prehensive introduction to general ontology matching

and merging methods.

3 COMPARISON OF RetFig,

GRhOOT, AND PLOKE

ONTOLOGY

In this section, we discuss the conceptual models of

the RetFig, GRhOOT, and Ploke ontology. Further,

we provide a comparison of rhetorical figure defi-

nitions in the RetFig (Serbian), GRhOOT (German)

and Ploke ontologies. In this paper, we use capital-

ized words to indicate a class name (e.g., Class), and

typewriter lower case words to indicate an individual

name (e.g., ind1) in an ontology. Names of rhetorical

figures are italicized on the first appearance.

3.1 Concepts of RetFig/GRhOOT:

Serbian and German Ontologies

RetFig (Mladenovi

´

c and Mitrovi

´

c, 2013) is a formal

domain ontology for rhetorical figures in the Serbian

language, written in OWL. Figures are classified ac-

cording to rhetorical and linguistic types and rhetori-

cal operations. It was inspired by the ontology devel-

oped by (Harris and DiMarco, 2009) and (Kelly et al.,

2010) in the scope of the RhetFig project. There,

rhetorical figures are classified based on Linguistic

Domain (e.g., phonological, morphological, and lex-

ical), neuro-cognitive pattern biases (e.g., repetition,

position, and similarity), and traditional categories

(e.g., trope and scheme). A figure can belong to more

than one class.

In the Serbian RetFig, the authors reduced the

number of Linguistic Entities to four: phonological,

Towards a Unified Multilingual Ontology for Rhetorical Figures

119

Table 1: Explanation of figures in different languages.

Figure Language Definition

Anadiplosis English The repetition of a word or word group on both sides of a clause or phrase

boundary.

Anadiplose German Repetition of the last word of a sentence at the beginning of the next

sentence.

Palilogija Serbian Repetition of the words at the end of a verse at the beginning of the next

verse.

Conduplicatio English Unpatterned perfect lexical repetition.

Epanalepse German Repetition of a word or group of words in a sentence (Dudenredaktion,

2022).

Epanalepsis English The repetition of a word or word group at the beginning and ending of

the same clause or phrase.

Epanadiplose German Repetition of a word at the beginning and end of a sentence/line.

Okruzivanje Serbian The same word is at the beginning and end of the sentence (verse).

Epanaphora English The occurrence of the same word or word group at the beginning of

proximal clauses or phrases.

Anapher German Repetition of the word in the beginning in successive sentences.

Anafora Serbian Repetition of the same words in the beginning (verse).

Epiphora English The occurrence of the same word or word group at the end of proximal

clauses or phrases.

Epipher German Inversed anaphora.

Epifora Serbian Repetition of the same words at the end (verses).

Epizeuxis English The immediate repetition of a word or word group with no other words

intervening.

Epizeuxis German Three or more repetitions of the same word/word group.

Epizeusa Serbian Repeating the same word several times in the same sentence or verse for

emphasis.

Gradatio English A sequence of anadiploses.

Gradation German Gradual increase, top term for climax/anticlimax.

Gradacija Serbian Transferring one word or word group from one sentence or verse to the

next sentence or verse in order to gradually increase or decrease the

strength of the initial statement.

Mesodiplosis English Lexical repetition of a word or word group in the middle of clauses or

phrases.

Symploce/Symploke English Combination of epanaphora and epiphora: The occurrence of the same

word or word group at the beginnings of two or more proximal phrases

or clauses while another word or word group occurs at the ends of those

same phrases or clauses.

Symploke German Combination of anaphora and epiphora.

Simploka Serbian Repetition of the same words at the beginning and at the end (verses).

Anaklaza Serbian Repeating the same word in the same verse for emphasis.

Antiklimax German Downward gradatio.

Emphase German Emphatic emphasis of a word, often acoustically or with exclamation

marks.

Emfaza Serbian Emphasis on words in a sentence. Exaggeration in the tone or expression

with which the writer or speaker emphasizes certain words, thoughts or

feelings. It can turn into force.

KEOD 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

120

morphological, pragmatic, and syntactic, and

do not concern themselves with neuro-cognition or

traditional categories. Instead, they modelled rhetori-

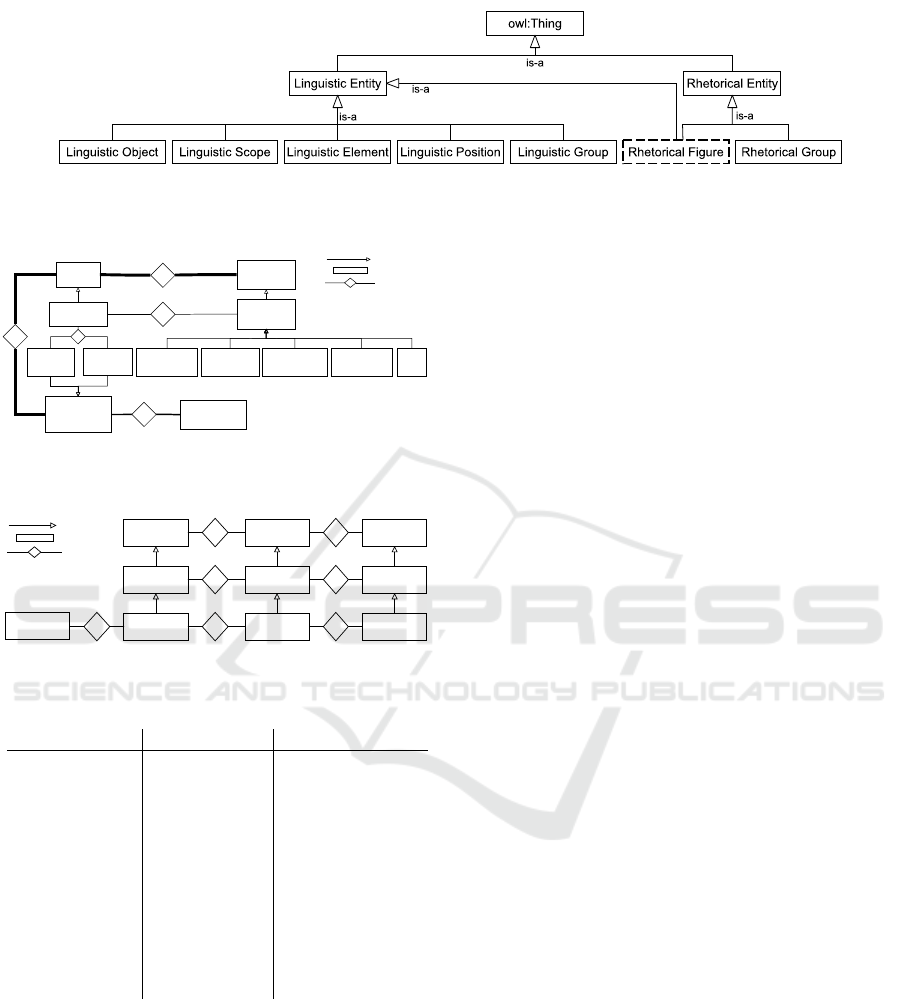

cal operations. The overall structure is shown in Fig-

ure 1. Each figure is assigned a LinguisticEntity and

a RhetoricalEntity. A LinguisticEntity has multiple

subclasses such as LinguisticObject, LinguisticScope,

LinguisticElement, etc. A rhetorical operation desc-

ribes how a rhetorical figure is formed, e.g.,

addition, omission, repetition, transposition,

joining, separation, or symmetry. These oper-

ations are similar to the Kind-Of classification in

RhetFig. For the RhetoricalEntity, RetFig differenti-

ates between figures of pronunciation, of meaning

tropes, of construction, and of thoughts. For

each figure, an English name is provided such that a

mapping to other linguistic ontologies is possible in

the future.

GRhOOT, the German RhetOrical OnTology, is

the adaption of the Serbian RetFig to the German

language. GRhOOT uses the same structure as Ret-

Fig (cf. Figure 1), however, some figures have been

adapted/added/omitted according to differences in the

definitions of figures in the Serbian and the German

language.

3.2 Concepts of the Ploke Ontology

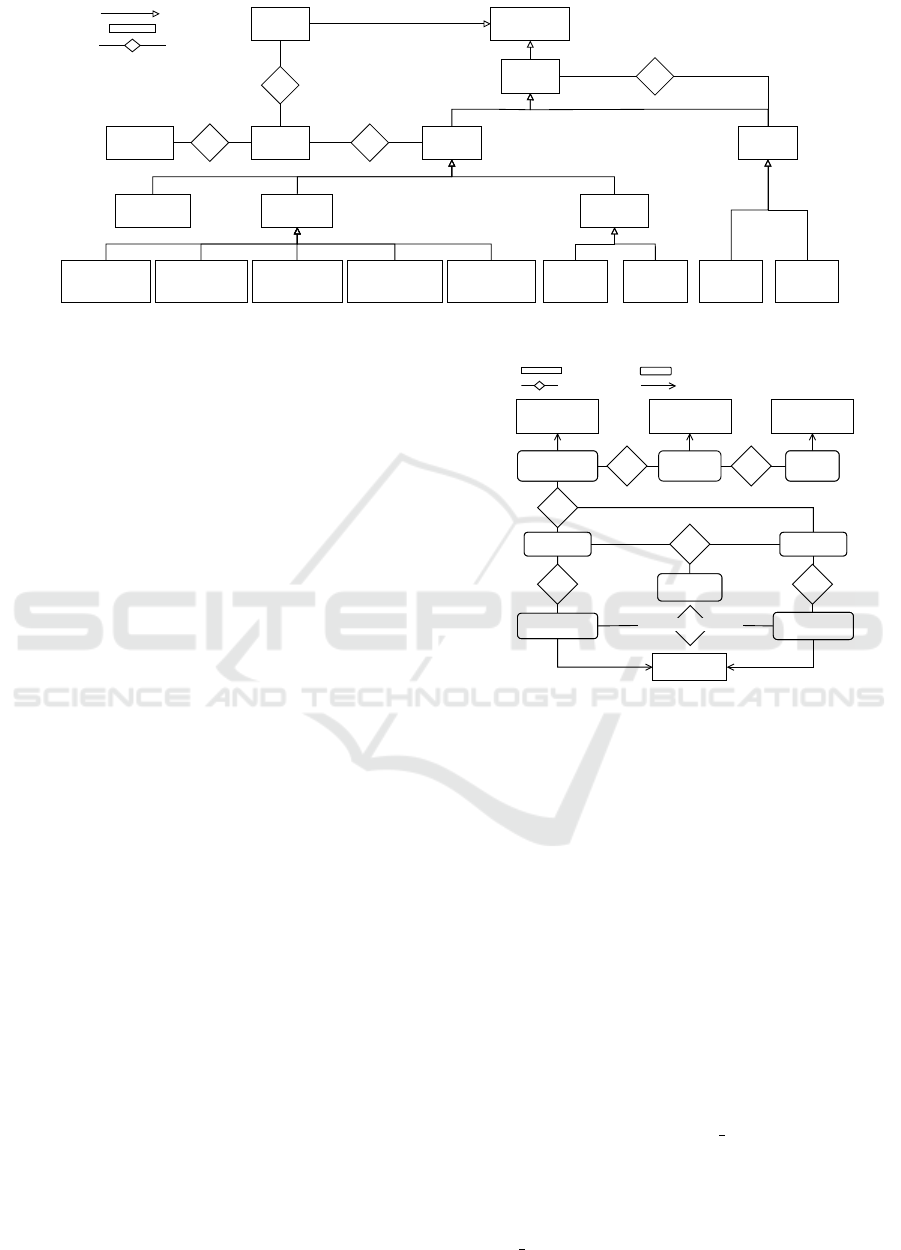

The Ploke ontology (Wang et al., 2021), as the

name suggests, deals with ploke, rhetorical figures

of perfect lexical repetition. At the top level, it

defines a class RhetoricalFigure, Form, and Neuro-

cognitiveAffinity with relations to depict a statement

which we refer to as the “neuro-cognitive path”: a

rhetorical figure has a form, the form triggers a set

of neuro-cognitive affinities that generate a set of at-

tentional and mnemonic effects (Wang et al., 2021).

Neuro-cognitive affinities are patterns that can be eas-

ily recognized by a human mind, generating atten-

tional and mnemonic effects that make certain con-

cepts more salient, aesthetically pleasing, and more

memorable (Harris et al., 2017). This is illustrated

by the highlighted path in Figure 2. The Ploke ontol-

ogy focuses on representing concepts specific to ploke

along this path.

Instead of treating ploke as a single figure, the

Ploke ontology adopts the view of Harris in which

ploke should be treated as a class of figures of perfect

lexical repetition (Harris, 2020). Figure 2 outlines

classes and relations in the Ploke ontology. A class

Ploke is defined as a subclass of RhetoricalFigure

and has a number of subclasses to represent the fig-

ures of perfect lexical repetition such as epanaphora,

epizeuxis, mesodiplosis, antimetabole, etc.

2

They

are defined in terms of their positions relative to the

clause structure, e.g., an epanaphora is a figure in

which words or word groups are repeated at the be-

ginning of a clause; or respective to other lexical

items, e.g., epizeuxis is a figure in which a word or

word group is repeated immediately. Each class as-

sociates with a corresponding subclass of Form. Two

classes, Repetition and Position are defined as sub-

classes of Neuro-cognitiveAffinity, each of which has

subclasses representing different types of lexical rep-

etition corresponding to subclasses of Ploke as shown

in Figure 4. There are other neuro-cognitive affini-

ties but repetition and position are the two most fun-

damental affinities triggered by ploke (Harris, 2020;

Wang et al., 2021). For example, in the Ploke ontol-

ogy, a class Epizeuxis is connected to an Epizeuxis-

Form, which triggers ImmediateRepetition. Each of

these is a subclass of Ploke, PlokeForm, and Rep-

etition respectively, which in turn are subclasses of

RhetoricalFigure, Form, and Neuro-cognitiveAffinity,

respectively. The hierarchy is illustrated in Figure 3.

3

As an enhancement of the Ploke ontology, a Repeti-

tion can be further classified into classes SingleRepe-

tition or NestedRepetition. A SingleRepetition is con-

nected to a class Element that refer to a word or word

group and has a position. A NestedRepetition is a

subclass of Repetition in which the elements are also

isntances of Repetition. For simplicity, we omit Nest-

edRepetition and refer to SingleRepetition as Repeti-

tion in this paper.

3.3 Figures of Perfect Lexical

Repetition in the Ontologies

For each figure of perfect lexical repetition, we com-

pared within the three ontologies if it exists in the

other languages in general and if it is modelled in the

ontologies, too. The result is shown in Table 2. A

dash indicates that a figure does not exist in this on-

tology.

Some figures like anaklaza, mesodiplosis, or an-

tiklimax, are only modelled in one ontology or only

in one of the ontologies considered as ploke. Only in

GRhOOT, antiklimax is considered as a figure of per-

fect lexical repetition, but klimax (climax) is not. It is

questionable if this is just due to a wrong classifica-

tion. One might notice, for instance, that epanalepsis

is not the same as the German figure epanalepse, but

epanadiplose. The terminology of rhetorical figures

is notoriously inconsistent. We want to look further

2

Definitions are listed in Table 1.

3

Relation names are omitted for readability.

Towards a Unified Multilingual Ontology for Rhetorical Figures

121

Figure 1: Structure of the RetFig ontology, adapted from (Mladenovi

´

c and Mitrovi

´

c, 2013).

Ploke

Anadiplosis Mesodiplosis Antimetabole ...

Ploke Form

Repetition

Conduplicatio

Rhetorical

Figure

Form

Neuro-

cognitive

Affinity

Position

Attentional

Effect

sublcass of

class

binary relation

Figure 2: Classes related to ploke in the Ploke ontology,

adapted from (Wang et al., 2021).

Ploke

Epizeuxis

Epizeuxis

Form

Repetition

Immediate

Repetition

Ploke

Form

Rhetorical

Figure

Neuro-cognitive

Affinity

Form

Element

sublcass of

class

binary relation

Figure 3: Classes related to Epizeuxis in the Ploke ontology.

Table 2: Comparison of figures of perfect lexical repetition.

Ploke Ontology Serbian RetFig German GRhOOT

Anadiplosis Palilogija Anadiplose

Conduplicatio – Epanalepse

Epanalepsis Okruzivanje Epanadiplose

Epanaphora Anafora Anapher

Epiphora Epifora Epipher

Epizeuxis Epizeusa Epizeuxis

Gradatio Gradacija Gradation

Mesodiplosis – –

Symploke Simploka Symploke

– Anaklaza –

– – Antiklimax

– Emfaza Emphase

into the definitions to spot differences and detect in-

consistencies. Table 1 provides the definitions from

each ontology for the respective figure. We provide

the English definitions (Harris and Di Marco, 2017)

that are used in the Ploke ontology, the German def-

initions (Berner, 2011) from GRhOOT, and the Ser-

bian definitions from the RetFig ontology.

4 INCONSISTENCIES OF THE

ONTOLOGIES

This section discusses types of inconsistencies be-

tween RetFig/GRhOOT and the Ploke ontology.

These inconsistencies fall under a more general clas-

sification of heterogeneity outlined by (Euzenat and

Shvaiko, 2013). We adapt those types of heterogene-

ity to introduce the following types of inconsistencies.

4.1 Model Inconsistency

Model inconsistency is a type of conceptual or seman-

tic heterogeneity, particularly an instance of differ-

ence in granularity or difference in perspective (Eu-

zenat and Shvaiko, 2013). The difference is caused

by the level of details represented for concepts in

each ontology. The most significant inconsistency

is that rhetorical figures are modelled as individu-

als in GRhOOT, but are modelled as classes in the

Ploke ontology. The former focuses on the relation

of rhetorical figures with linguistic entities in gen-

eral, in which it is sufficient to represent each rhetor-

ical figure as an individual. The latter models a spe-

cific class of figures, i.e., ploke, which requires the

representation of the hierarchical relations between

ploke and its subclasses, and their relations to cor-

responding subclasses of repetition and position. For

example, in GRhOOT, the figure epizeuxis is repre-

sented by an individual epizeuxis, an instance of the

class RhetoricalFigure, with axioms shown in Table 3.

In the Ploke ontology, the figure epizeuxis is repre-

sented by a class Epizeuxis, an indirect subclass of

the class RhetoricalFigure. An instance of Epizeuxis

is an individual representing a specific epizeuxis,

e.g., epiz1, which is connected to epiz1form and

immediateRep1 which are instances of the Epizeux-

isForm and ImmediateReptition, respectively. The re-

lations are outlined in Figure 5.

In order to resolve this inconsistency, classes that

are defined in the Ploke ontology will replace the

corresponding individuals in GRhOOT while main-

KEOD 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

122

Single

Repetition

Neuro-cognitive

Affinity

Relative

Repetition

Nested

Repetition

Cross-Boundary

Repetition

Constituent-

Medial Repetition

Constituent-

Final Repetition

Immediate

Repetition

Reversed

Repetition

Gradatio

Repetition

Element

Word/Word

Group

refers

To

Unpatterned

Repetition

Respective

Repetition

Between

Repetition

Constituent-

Initial Repetition

Outer-Boundary

Repetition

Position

sublcass of

class

binary relation

Repetition

Figure 4: Repetition in the Ploke ontology, modified based on (Wang et al., 2021).

taining conceptual and ontological inconsistencies as

discussed in the following sections. Individuals of

rhetorical figures that are not part of the Ploke on-

tology remain untouched. These individuals can be

used as placeholders for future extension of potential

ontologies in the rhetorical figure domain.

4.2 Conceptual Inconsistency

Conceptual inconsistency is a combination of concep-

tual heterogeneity and terminological heterogeneity

(Euzenat and Shvaiko, 2013). It is caused by dif-

ferences in definitions of rhetorical figures and the

scopes of the ontologies. Conceptual inconsistency

can be terminological or due to differences in cover-

age.

4.2.1 Terminological Inconsistency

Terminological inconsistencies occur when different

names are used for the same rhetorical figures, or

when a rhetorical figure is represented as different en-

tities. For example, epizeuxis is defined as a figure

in which words or word groups are repeated imme-

diately in the Ploke ontology, but defined as a figure

in which words or word groups are repeated three or

more times in GRhOOT.

In order to resolve terminological inconsistencies,

the definitions will be carefully compared. In the case

of epizeuxis as mentioned above, we first distinguish

representations of epizeuxis in the ontologies by cre-

ating a class EpizeuxisG for epizeuxis in GRhOOT.

The class Epizeuxis follows the definition in Figure 3

in the Ploke ontology.

Figure 5 demonstrates how epiz1, an instance of

Epizeuxis, is represented graphically using the phrase

“long, long ago”. Recall that epiz1 is connected

to immediateRep1, an instance of ImmediateRepeti-

tion, which is connected to two instances of Element,

Immediate

Repetition

immediateRep1

e1 e2

position(e1) position(e2)

Position

refers

To

"long"

epiz1

epiz1form

Epizeuxis

Form

Epizeuxis

binary relation

class

instance of

individual

Immediate

Repetition

immediateRep1

e1

position(e1)

"long"

Position

position(e2)

e2

epiz1

immediately precedes

Figure 5: An instance of Epizeuxis in the Ploke ontology of

the phrase “long, long ago”.

e1 and e2. The Element class represents each occur-

rence of the repeated word or word group. An in-

stance of Element refers to an instance of the class

Word/WordGroup and is connected to an instance of

the class Position. The position of the first element

of “long”, i.e., e1, immediately precedes the second

element, i.e., e2. Both e1 and e2 refer to the word

“long”. Implicitly, the position of e2 immediately

follows the position of e1. There are two cases we

consider for the definition of EpizeuxisG:

1. Words or word groups repeat 3 or more times.

2. Words or word groups repeat 3 or more times. im-

mediately, e.g., “a long, long, long time ago”.

In case 1, EpizeuxisG is not necessarily an

epizeuxis, it is a subclass of Ploke distinguished from

Epizeuxis. A new class Ploke 3 is created as a sub-

class of Ploke with additional cardinality constraints

on number of occurrences associated with the corre-

sponding subclass of Repetition. In case 2, Epizeux-

isG is a more specified version of both the class

Ploke 3 and Epizeuxis, therefore a subclass of both.

Towards a Unified Multilingual Ontology for Rhetorical Figures

123

The resulting classes and relations are shown in Fig-

ure 6.

Another example of terminological inconsistency

regards the figure epanalepsis. Its corresponding Ser-

bian term is okruzivanje, but in German the name

is epanadiplose, whereas an epanalepse in German

is just a repetition of words without any constraints,

similar to conduplicatio in English. We create

classes EpanadiploseG and EpanalepseG to represent

epanadiplose and epanalepse defined in GRhOOT re-

spectively. Conduplicatio and Epanalepsis are already

subclasses of the class Ploke in the Ploke Ontology

as shown in Figure 2. Therefore, we construct the

following mappings from GRhOOT to the Ploke on-

tology regarding epanalepsis: 1) EpanadiploseG →

Epanalepsis; 2) EpanalepseG → Conduplicatio.

4.2.2 Inconsistency in Coverage

Different sets of rhetorical figures are included in each

ontology due to difference in coverage and perspec-

tive (Euzenat and Shvaiko, 2013). In order to resolve

coverage inconsistencies, each disjoint figure listed in

Section 3.3 will be checked individually. Since the

Ploke ontology has the most specific details, it is used

as baseline ontology. We check whether the figures

from GRhOOT can fit into the model of the Ploke on-

tology. For example, since mesodiplosis is the only

figure that is only present in the Ploke ontology and

as this ontology serves as baseline, thus no further ac-

tions need to be taken for mesodiplosis.

On the other hand, there are three figures included

in the Serbian RetFig and GRhOOT but not in the

Ploke ontology, i.e., antiklimax, anaklaza, and em-

phase. Antiklimax, an inversed version of the figure

climax, is not considered as a figure of perfect lexical

repetition in the Ploke ontology. Recall from Section

2, climax is a figure that consists of anadiplosis and

gradatio but also incrementum which is not a figure of

perfect lexical repetition (O’Reilly et al., 2018; Black

et al., 2019). Therefore, the Ploke ontology includes

only classes Anadiplosis and Gradatio as subclasses

of Ploke, but no class to represent incrementum nor

climax. Anaklaza and emphase are figures of perfect

lexical repetition that are not represented in the Ploke

ontology which will be discussed in the following sec-

tion.

4.3 Ontological Inconsistency

This type of inconsistency deals with domain-specific

concepts that are represented differently in each on-

tology due to the different purposes and scopes when

modelling the ontologies. This is referred to as

semiotic or pragmatic heterogeneity (Euzenat and

Shvaiko, 2013). A significant ontological inconsis-

tency is how repetition is represented in each ontol-

ogy. In the Serbian RetFig and GRhOOT ontologies,

repetition is merely implicitly defined as object prop-

erties. Four different subproperties of the repetition

property are differentiated here: Repetition of another

form, of the same form, with different meaning, of

different kind. Individual elements like word, sen-

tence, or phrase can be assigned to those properties.

In the Ploke ontology, repetition is represented as a

subclass of Neuro-cognitiveAffinity as demonstrated

in Figure 5. It includes more details such as sub-

classes to represent different types of repetition, the

class Element to represent occurrences of repeated

words or word groups, and their positions. There-

fore, the ontologies are merged based on the Ploke on-

tology while incorporating any suitable axioms from

GRhOOT regarding a specific rhetorical figure of per-

fect lexical repetition. Again, we demonstrate this

with epizeuxis as an example. In GRhOOT, an in-

dividual Epizeuxis is defined with the axioms in Ta-

ble 3, where all values are individuals. Repetition and

position orientation of epizeuxis are only implicitly

defined with the object properties isARepeatableEle-

mentOfTheSameForm and isInPosition.

Table 3: Axioms of Epizeuxis in GRhOOT.

Object Property Value

isARepeatableElement

OfTheSameForm

Wordelement

isInObject Wordobject

isInPosition Whole-Succesive

isLinguisticGroup Syntactic

isRhetoricalGroup FigureOfSpeech

isInArea Sentence

isInArea Verse

As shown in Figure 5, the Ploke ontology de-

fines repetition with an explicit and more detailed

definition such as each occurrence of the repeated

words or word groups. A class ImmediateRepeti-

tion, a subclass of Repetition, is used to represent

the specific type of repetition triggered by the form of

an epizeuxis represented by an EpizeuxisForm class.

The positions of the repeated words or word groups

are also defined with a Position class. An object prop-

erty immediatelyPrecedes, which is a subproperty of

precedes (similarly for immediatelyFollows and fol-

lows) represents the orientation of positions explicitly.

Another example of ontological inconsistency is

the rhetorical figure emphase in GRhOOT. It is de-

fined as emphasis of a word, often acoustically or

with exclamation mark (Berner, 2011). It deals with

phonological or orthographic methods of applying an

emphasis effect. In the case of ploke, the emphasis

KEOD 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

124

Epizeuxis

Repetition_3

Element

3,*

Ploke

Ploke_3

Ploke_3

Form

Single

Repetition

Ploke

Form

EpizeuxisG

2,*

sublcass of

class

binary relation

Repetition

Figure 6: New classes Ploke 3 and EpizeuxisG added to resolve Case 1 and 2 respectively.

effect naturally applies to every ploke since the re-

peated words or word groups would already increase,

to some extent, the salience of the concept carried as

part of the attentional effect (Harris, 2020), thus em-

phasizing the concept of the repeated word or word

group. The Ploke ontology implicitly represents this

emphasis effect as part of the neuro-cognitive path

(the highlighted path in Figure 2). That is, the form

of a rhetorical figure triggers neuro-cognitive affini-

ties (e.g., repetition) which generate attentional and

mnemonic effect (e.g., salience). Since the Ploke on-

tology does not deal with phonological, orthographic,

or punctuation aspects of natural language, it does not

include emphase as part of its representation. This

also suggests that the figure anaklaza is equivalent

to conduplicatio under this representation, since the

only difference between the definitions is the notion

of ‘emphasis’ as shown in Table 1.

Neuro-cognitive

Affinity

Repetition Position

......Metaphor Rhyme Sarcasm

Linguistic EntitiesRhetorical Entities

Ploke

Epanaphora Anadiplosis

......

Epizeuxis

Antimetabole

RetFig/

GRhOOT

+

Ploke

RetFig/

GRhOOT

Ploke

Figure 7: Combination of the RetFig, GRhOOT, and Ploke

ontologies.

5 COMBINING THE RetFig,

GRhOOT, AND PLOKE

ONTOLOGIES

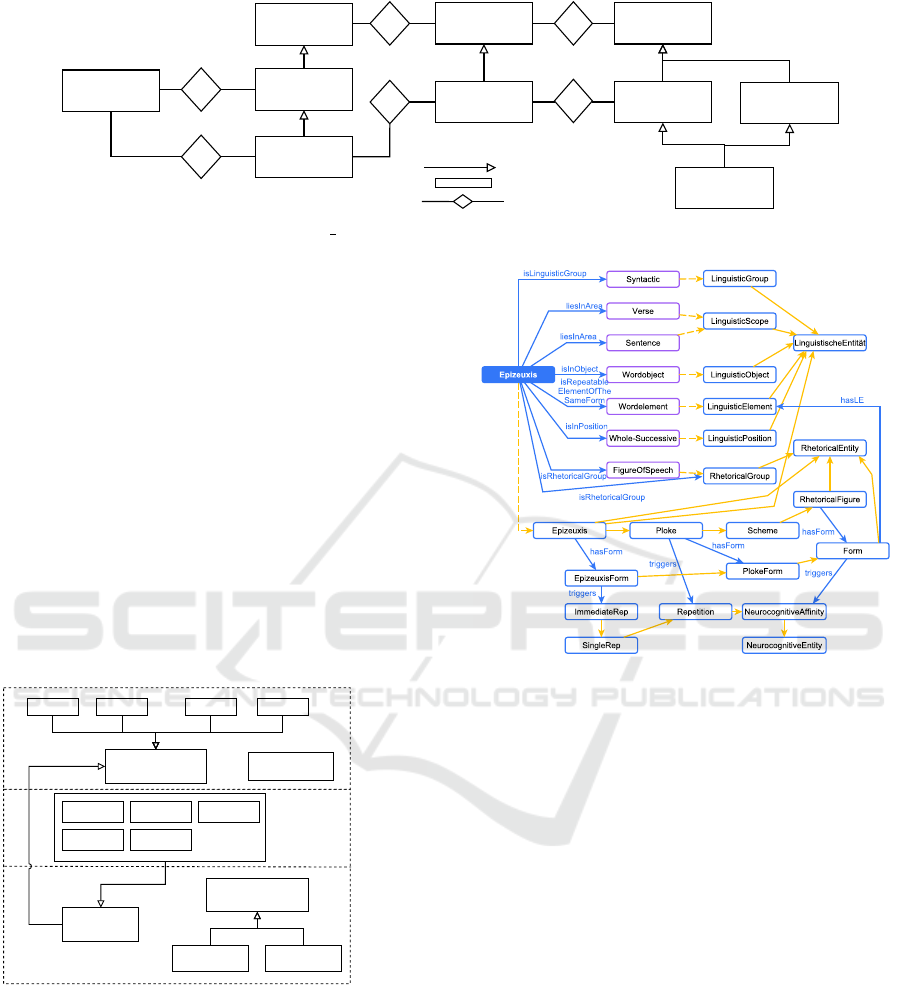

The resulting ontology is a combination of the Ser-

bian RetFig, GRhOOT and Ploke ontology as shown

Figure 8: Prot

´

eg

´

e’s entity graph for the figure Epizeuxis.

in Figure 7. Concepts that apply to only one ontol-

ogy remain unchanged, e.g., subclasses of Linguis-

ticEntities and Neuro-cognitiveAffinity, respectively.

The middle section of Figure 7 indicates the over-

lapping concepts in all three ontologies. These con-

cepts are subclasses of ploke represented by newly

formed classes to incorporate existing concepts from

both GRhOOT and the Ploke ontology. Note that only

subclassOf relations are shown in Figure 7. The OWL

ontology was implemented using WebProt

´

eg

´

e (Tudo-

rache et al., 2013). Figure 8 shows the entity graph

of the figure epizeuxis, represented by an individual

Epizeuxis with a type of the class Epizeuxis. The

axioms from GRhOOT shown in Table 3 are present

here again. Additionally, the individual represent-

ing epizeuxis is now connected to a class of Rhetor-

icalFigure whose form triggers ImmediateRepetition.

This is a subclass of Repetition, which in turn is a

subclass of Neuro-cognitiveAffinity. As Epizeuxis is

a type of Ploke, it is marked as a subclass of Ploke

which is a subclass of the rhetorical figures of the cat-

egory Scheme. These are all rhetorical entities be-

longing to the top class RhetoricalEntity.

Towards a Unified Multilingual Ontology for Rhetorical Figures

125

6 CONCLUSION

The resulting ontology for rhetorical figures of perfect

lexical repetition is a combination of three different

ontologies that tackles not only multilingual differ-

ences but also conceptual and terminological incon-

sistencies. It is tightly connected but still modular.

We have shown the representations of different fig-

ures of perfect lexical repetition in the ontologies and

their definitions. The inconsistencies were identified

to be later resolved.

Future work includes the establishment of a gen-

eralized framework for ontologies in the domain of

rhetorical figures, as also suggested by (Mitrovi

´

c

et al., 2017). This framework could be similar to the

CIDOC-Conceptual Reference Model (Doerr, 2003)

that is used in the domain of cultural heritage infor-

mation. It is an ontology which is restricted to prede-

fined semantics that are specific in the domain of cul-

tural heritage. For the domain of rhetorical figures, a

standard notation of text elements is required (Harris

and DiMarco, 2009). Furthermore, more figures can

be combined in one unified ontology.

We paved the way for combining ontologies of

rhetorical figures in a potentially generalizable way:

It involves much domain-specific knowledge. We

hope for an automated tool that incorporates rhetori-

cal figure domain knowledge as more rhetorical figure

ontologies are being developed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The project on which this report is

partly based was funded by the So-

cial Sciences and Humanites Research

Council of Canada and the German

Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF)

under the funding code 01—S20049. The authors are

responsible for the content of this publication.

REFERENCES

Alliheedi, M. and Di Marco, C. (2014). Rhetorical figu-

ration as a metric in text summarization. In Cana-

dian Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 13–

22. Springer.

Berner, G. (2011). Vollst

¨

andiges Kompendium der

rhetorischen Mittel, Stilfiguren und Tropen f

¨

ur Ober-

stufensch

¨

uler und Studienanf

¨

anger. GRIN Verlag,

M

¨

unchen.

Black, L. A., Tu, K., O’Reilly, C., Wang, Y., Pacheco, P.,

and Harris, R. A. (2019). An ontological approach to

meaning making through path and gestalt foreground-

ing in climax. The American Journal of Semiotics,

35(1/2):217–249.

Caselli, T., Basile, V., Mitrovi

´

c, J., Kartoziya, I., and

Granitzer, M. (2020). I feel offended, don’t be abu-

sive! implicit/explicit messages in offensive and abu-

sive language. In Proceedings of the 12th Lan-

guage Resources and Evaluation Conference, pages

6193–6202, Marseille, France. European Language

Resources Association.

Clarke, E. L. (2019). The Relo-KT Process for Cross-

Disciplinary Knowledge Transfer. PhD thesis, Trinity

College Dublin, Ireland.

Doerr, M. (2003). The cidoc conceptual reference module:

an ontological approach to semantic interoperability

of metadata. AI magazine, 24(3):75–75.

Dudenredaktion (2022). Epanalepse. https://www.duden.

de/rechtschreibung/Epanalepse. Accessed: 2022-02-

17.

Euzenat, J. and Shvaiko, P. (2013). Ontology Matching.

Springer Science & Business Media.

Fahnestock, J. (2002). Rhetorical Figures in Science. Ox-

ford University Press on Demand.

Green, N. L. (2020). Recognizing rhetoric in science pol-

icy arguments. Argument & Computation, 11(3):257–

268.

Green, N. L. and Crotts, L. J. (2020). Towards automatic

detection of antithesis. In Computational Models of

Natural Argument, pages 69–73.

Harris, R. and DiMarco, C. (2009). Constructing a rhetori-

cal figuration ontology. In Persuasive Technology and

Digital Behaviour Intervention Symposium, pages 47–

52.

Harris, R. A. (2020). Ploke. Metaphor and Symbol,

35(1):23–42.

Harris, R. A. and Di Marco, C. (2017). Rhetorical figures,

arguments, computation. Argument & Computation,

8(3):211–231.

Harris, R. A., Di Marco, C., Mehlenbacher, A. R., Clap-

perton, R., Choi, I., Li, I., Ruan, S., and O’Reilly,

C. (2017). A cognitive ontology of rhetorical figures.

Cognition and Ontologies, pages 18–21.

Horrocks, I., Patel-Schneider, P. F., Boley, H., Tabet, S.,

Grosof, B., Dean, M., et al. (2004). Swrl: A semantic

web rule language combining owl and ruleml. W3C

Member submission, 21(79):1–31.

Java, J. (2015). Characterization of Prose by Rhetorical

Structure for Machine Learning Classification. PhD

thesis, Nova Southeastern University.

Karp, M., Kunanets, N., and Kucher, Y. (2021). Meiosis

and litotes in the catcher in the rye by jerome david

salinger: text mining. In CEUR Workshop Proceed-

ings, volume 2870, pages 166–178.

Kelly, A. R., Abbott, N. A., Harris, R. A., DiMarco, C.,

and Cheriton, D. R. (2010). Toward an ontology of

rhetorical figures. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM In-

ternational Conference on Design of Communication,

pages 123–130.

K

¨

uhn, R., Mitrovi

´

c, J., and Granitzer, M. (2022). GRhOOT:

Ontology of Rhetorical Figures in German. In Pro-

ceedings of The 13th Language Resources and Eval-

KEOD 2022 - 14th International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

126

uation Conference, Marseille, France. European Lan-

guage Resources Association.

Lagutina, N. S., Lagutina, K. V., Boychuk, E. I.,

Vorontsova, I. A., and Paramonov, I. V. (2020). Auto-

mated rhythmic device search in literary texts applied

to comparing original and translated texts as exempli-

fied by english to russian translations. Automatic Con-

trol and Computer Sciences, 54(7):697–711.

Lawrence, J., Visser, J., and Reed, C. (2017). Harnessing

rhetorical figures for argument mining. Argument &

Computation, 8(3):289–310.

Lemmens, J., Markov, I., and Daelemans, W. (2021). Im-

proving hate speech type and target detection with

hateful metaphor features. In Proceedings of the

Fourth Workshop on NLP for Internet Freedom: Cen-

sorship, Disinformation, and Propaganda, pages 7–

16.

McGuinness, D. L., Van Harmelen, F., et al. (2004). Owl

web ontology language overview. W3C recommenda-

tion, 10(10):2004.

Mitrovic, J., O’Reilly, C., Harris, R. A., and Granitzer, M.

(2020). Cognitive modeling in computational rhetoric:

Litotes, containment and the unexcluded middle. In

ICAART (2), pages 806–813.

Mitrovi

´

c, J., O’Reilly, C., Mladenovi

´

c, M., and Handschuh,

S. (2017). Ontological representations of rhetorical

figures for argument mining. Argument & Computa-

tion, 8(3):267–287.

Mladenovi

´

c, M. and Mitrovi

´

c, J. (2013). Ontology of

rhetorical figures for serbian. In International Confer-

ence on Text, Speech and Dialogue, pages 386–393.

Springer.

Musolff, A. (2015). Dehumanizing metaphors in uk immi-

grant debates in press and online media. Journal of

Language Aggression and Conflict, 3(1):41–56.

O’Reilly, C. and Paurobally, S. (2010). Lassoing rhetoric

with owl and swrl. Unpublished MSc dissertation.

Available: http://computationalrhetoricworkshop.

uwaterloo.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2016/06/

LassoingRhetoricWithOWLAndSWRL.pdf .

O’Reilly, C., Wang, Y., Tu, K., Bott, S., Pacheco, P., Black,

T. W., and Harris, R. A. (2018). Arguments in grada-

tio, incrementum and climax; a climax ontology. In

Proceedings of the 18th workshop on Computational

Models of Natural Argument. Academic Press.

Shakespeare, W. (2014). The complete works of William

Shakespeare. Race Point Publishing.

Strommer, C. W. (2011). Using Rhetorical Figures and

Shallow Attributes as a Metric of Intent in Text. PhD

thesis, University of Waterloo.

Suckling, S. J. (c. 1637). Aglaura.

Tudorache, T., Nyulas, C., Noy, N. F., and Musen, M. A.

(2013). Webprot

´

eg

´

e: A collaborative ontology editor

and knowledge acquisition tool for the web. Semantic

web, 4(1):89–99.

Wang, Y., Harris, R. A., and Berry, D. M. (2021). An ontol-

ogy for ploke: Rhetorical figures of lexical repetitions.

CAOS 2021: 5th Workshop on Cognition And Ontolo-

gieS.

Towards a Unified Multilingual Ontology for Rhetorical Figures

127