Culture, Economic Preference and Economic

Development with Python: Evidence from Two New Datasets

Linwei Ma

Tianjin University of Commerce, Tianjin, China

Keywords: Culture, Preference, Economic Growth.

Abstract: With the development of society, economy and technology, an increasing number of scholars are attaching

more value to the power of culture. Consequently, this paper uses Python, a computer programming language,

as a research tool for data analysis and examines the relationship between culture and economic outcomes

using two new datasets of cultural features and economic preferences across countries, and based on two

indicators of economic outcomes, income per worker and total factor productivity. In the course of the study,

our independent variable data cultural economic preferences are derived from Geert Hofstede ’ s Six-

dimensional Cultural Index and Global Preferences Survey. In addition, our dependent variables income per

worker and total factor productivity are obtained from the Penn World Table. With a known strong positive

relationship between the cultural preference for individualism and economic outcomes, we initially screen out

the preferences for a positive relationship with individualism by drawing a heat map model using Python.

Then, we verify the conjecture that there is a positive correlation between cultural economic preferences and

economic outcomes by producing scatter plots with the dependent variable added. The final regression model

is made to determine the extent to which the independent and dependent variables are correlated by the

magnitude of the correlation coefficient. Through our research, we find that culture has a significant impact

on economic performance.

1 INTRODUCTION

The question of how culture drives economic growth

has attracted perennial interest in both scholarly

research and popular discussions in the public sphere.

For instance, one of the most influential thinkers in

history on this topic Weber (Weber 1930). attributed

the rise of modern capitalism to protestant ethics, in

particular Calvinist. Some recent empirical work in

economics explores the economic impacts of certain

narrowly defined dimensions of cultural factors, such

as individualism v.s. collectivism Gorodnichenko

and Roland (Gorodnichenko, Roland, 2017), patience

(Chen 2013), and social structure (Granovetter 2005),

etc. The challenge in studying culture and its resulting

economic effects is that it encapsulates an extensive

number of dimensions of social features, not to

mention the difficulty of its measurement due to its

time-varying nature and the substantial variations

across regions, groups, and individuals. According to

Gorodnichenko and Roland (Gorodnichenko,

Roland, 2017), culture is defined in general as the set

of values and beliefs people have about how the

world (both nature and society) works, as well as the

norms of behavior derived from that set of values.

This paper, although similarly, adopts a more specific

definition of the culture. We treat each particular

cultural characteristic as a stable/relatively

commonly shared individual and social preferences

of economic agents making decisions. More

specifically, we use four groups of cultural economic

preferences as independent variables. They are:

Individualism

Patience and Long-term Orientation

Risk Attitude

Social Preferences

Also, I use two economic outcomes, income per

worker and total factor productivity, as measures of

the dependent variables. Based on the existing

economic models we find that the independent

variables have a direct effect on individual economic

behavior and macroeconomic performance. This

paper can be seen as an extension of Gorodnichenko

and Roland (Gorodnichenko, Roland, 2017) in terms

of the cultural variables considered and the data set

utilized. We replicate the positive relationship

854

Ma, L.

Culture, Economic Preference and Economic Development with Python: Evidence from Two New Datasets.

DOI: 10.5220/0011355500003440

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management (BDEDM 2022), pages 854-863

ISBN: 978-989-758-593-7

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

between individualism and economic performance as

measured by GDP per capita that they found in the

paper. Then, the same framework is extended to other

variables.

We utilize two cross-country databases to study

the economic effects of the culture. Both databases

are considered as possibly the best large-sample

measurements of selective culture characteristics by

existing research. The first data set is the same data

set used in Gorodnichenko and Roland

(Gorodnichenko, Roland, 2017), Geert Hofstede's

six-dimensional culture index, (Hofstede 2001). And

the second additional data set is from the Gallop

Global Survey of Economic Preferences (Falk, et al,

2018), which measures different economic

preferences such as patience, risk attitudes, etc. By

using the same economic outcome measures and the

same regression specification as in their paper, this

paper finds that not only the degree of individualism

is positively associated with economic outcomes, but

also other cultural and preference characteristics can

have a profound effect on economic outcomes. In

addition to this, there is a correlation between data on

cultural dimensions and data on preference

characteristics. Thus, the paper has some credibility

in demonstrating the correlation between different

cultural dimensions and preferences and economic

outcomes, and reflects some cross-country

differences.

1.1 Literature Review

This paper is related to three strands of literature. The

first strand of the literature which is the most related

to this paper is research that examines the relationship

between culture, economic preferences and economic

outcomes. Papers by Algan and Cahuc (Algan, Cahuc

2007), Birchenall (Birchenall 2014), Brock and

Brighouse (Brock, Brighouse 2006) as well as Greif

(Greif 1994) explore the impact of these variables on

economic growth from the perspective of

sociocultural preferences such as social attitudes,

social network structures, social interactions, unique

cultures, and relevant social organizations. Hofstede

(Hofstede 2001) argues that corporate culture may

play a crucial role in a company's profitability and

long-term development. Another paper from Lucas Jr

and Moll (Lucas, Moll 2014) shows the way people

with different levels of productivity think, and social

activities may determine the current level of

production in the economy and its actual growth rate.

Historical variables such as literacy and political

system as tools can also explore the causal

relationship between culture and economic

development, a conclusion reflected in the paper by

Tabellini (Tabellini 2010). It is worth noting that

Gorodnichenko and Roland (Gorodnichenko, Roland

2017) discussed the relationship between

individualism-collectivism dimension of culture and

innovation and long-term growth. Doepke and

Zilibotti (Doepke, Zilibotti 2014) discussed the two-

way relationship based on the single relationship

between culture and economy, and provided different

research perspectives. My thesis was improved on the

basis of their research, and added preference features

on the basis of cultural dimension.

The second line of literature broadly explores the

driver of economic growth beyond culture and

preferences. Other important factors discovered in the

literature includes institutions, natural endoment,

religions and so on. The paper by Acemoglu and

Johnson (Johnson 2005) finds that property rights

regimes have first-order effects on long-run economic

growth, investment, and financial development. In

addition to this, Hall and Jones (Hall, Jones, 1999)

find that differences in social infrastructure across

countries lead to large differences in capital

accumulation, educational attainment, and

productivity, and thus make income vary widely

across countries. Perhaps a revolution can also be a

major influence and drive history. For example, the

consumer goods revolution represented in the paper

by Greenwoodetal. (Greenwoodetal 2005) helps

explain the rise in married female labor force

participation that occurred in the last century. In our

research we need to broaden our horizons to

constantly incorporate fresh perspectives because the

factors that influence the economy can be diverse.

Acemogluetal. (Acemogluetal 2002) examined the

relationship between geographic factors and

economic prosperity, and Ashraf and

Galor (Ashraf,

Galor 2012) hypothesized, on the basis of geographic

factors, that prehistoric Homo sapiens migrated out of

Africa to various global settlements. The variation in

migration distance of prehistoric Homo sapiens out of

Africa to various settlements around the globe

influenced genetic diversity and had a persistent hump

effect on economic growth.

The third strand of literature examines the effect of

culture on other specific economic outcomes other

than economic growth, such as innovation. The paper

by Bisin and Verdier (2001) examines the population

dynamics of preference characteristics in a model of

cultural intergenerational transmission. We find that

economists have recently devoted considerable

attention to women. For example, Fernandez and

Fogli (2009) and Tertilt (2005) published enlightening

papers exploring the impact of culture on female

Culture, Economic Preference and Economic Development with Python: Evidence from Two New Datasets

855

fertility. In addition to this, Granovetter (2005)

suggests that social structure and social networks may

influence hiring, prices, productivity and innovation,

and Greenwood and Guner (2010) explore the

inextricable relationship between individuals'

adherence to social norms and morality and

technological progress in the economy, which merits

further study. My paper improves on the study of

Gorodnichenko and Roland (2017) by adding data on

preference characteristics to the cultural dimension,

making it richer.

2 DATA

2.1 Geert Hofstede’s Six-Dimensional

Cultural Index

Some scholars in economics and other fields have

found that culture affects how people make decisions

about things, and thus how society as a whole

functions. If we want to study how people's

preferences affect economic outcomes, we need to

quantify ‘culture’.

Individuals who grow up in different cultures, and

are indoctrinated from an early age, will have very

different preferences for things. Culture itself is

abstract and complex, so it is difficult to measure.

Thankfully, the Dutch social psychologist Geert

Hofstede has made a groundbreaking research on the

culture of modern countries and put forward the

theory of cultural dimension. The concept of

dimensions is not hypothetical, but is derived through

summary induction.

The depth and breadth of research on cultural

dimensions has evolved with the times. Currently,

cultural dimensions have evolved from the initial four

dimensions of values, behaviors, institutions, and

multinational organizations to six dimensions to

measure values. They are:

Power Distance: emphasizes how the fact that

people differ in physical and intellectual

ability is treated in a society. Countries with a

high power distance index may have

inequalities in power and wealth that grow

stronger over time; while countries with a low

power distance index work to reduce these

inequalities.

Individualism versus Collectivism: Emphasis

on the relationship between the individual and

1

An explanation of long-term versus short-term

orientation comes from Charles W.L. Hill's 1993 book

the collective group. In individualistic

societies, relationships between people are

looser, with the goal of individual

achievement; in collectivistic societies,

human ties are stronger, with the goal of

collective success.

Uncertainty Avoidance: refers to the degree to

which culture enables members of society to

accept unclear situations and tolerate

uncertainty.

Masculinity versus Femininity: This

dimension is mainly used in order to

determine whether the society in which one

lives is a masculine or feminist society.

Masculinity mainly includes characteristics

such as competitiveness and assertiveness,

while femininity mainly includes

characteristics such as being more modest and

attentive. Generally speaking, this distinct

gender difference creates a different color

culture. In societies that are more masculine,

gender differences create a greater difference

in jobs; in societies that are more feminist,

there is no significant difference between the

jobs held by men and women.

Long-term Orientation versus Short-term

Orientation: This dimension measures the

degree of acceptance of people in different

cultures for deferred enjoyment of material

and spiritual satisfaction. It measures people's

attitudes toward issues such as time,

inheritance, status hierarchy, face, respect for

tradition, exchange of gifts, and helping each

other. This interpretation comes from Charles

W.L. Hill

1

.

Indulgence versus Restraint: This dimension

is essentially a measure of happiness, whether

simple pleasures are satisfied. The greater the

degree to which society allows for people's

basic needs and desire to enjoy life's pleasures,

the greater the value of their own indulgences

will be, and the less people will discipline

themselves. This is the latest dimension

added.

Geert Hofstede and his team have studied and

collected data on the size of cultural dimensions in

109 countries around the world, covering all seven

continents and major regions of the world. In this

article we use a revised version from 2015 to assist in

the study.

International Business: Competing in the Global

Marketplace.

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

856

2.2 Global Preferences Survey

The Global Preference Survey collected preference

data from 80,000 people in 76 geographically and

culturally diverse countries around the world. These

countries are on different continents and have

different levels of cultural and economic

development. With an average sample size of 1,000

people per country, these respondents represent 90

percent of the world's population and income, making

these samples more global in perspective. These

countries include 15 countries in the Americas, 25 in

Europe, 22 in Asia Pacific, and 14 in Africa, 11 of

which are sub-Saharan African countries. The

specific preference survey is a measure of

respondents' propensity for ways and actions through

a quantitative item and a qualitative question.

Researchers ask respondents in a choice scenario a

number of questions and self-assess respondents'

preferences on a Likert scale (Likert scale is an 11-

point scale).

This Preference Survey measures and collects

data sets on patience, risk-taking, trust, altruism,

positive reciprocity, and negative reciprocity in

different countries. These preferences influence

individuals' choices in a variety of contexts and also

help us to explore the impact on specific economic

outcomes and the prediction of important economic

behaviors based on cultural dimensions in

combination with preferences. They can also provide

control variables if we want to identify the causal

effects of other factors associated with preferences.

Since global preferences cover the preferences of a

representative sample of each country, they provide a

better indication of country-level averages and

become the best choice for our study. This data set is

divided into a country-level data set and an

individual-level data set. The country level shows the

average behavioral performance of the population of

the whole country with respect to six preferences; the

individual level is the conclusion drawn by the survey

agency interviewing a specific number of people

within a country from different regions, ages,

genders, and even languages. Both can be used for

our in-depth study of macroeconomics and

microeconomics. Here we use country-level data:

Patience/Time Preference: Patience comes

from people's understanding, respect and

tolerance of things, as well as a measure of

opportunity cost. The willingness to give up

what is good for you today in order to gain

more in the future is high.

2

Notes.—Source: The fifth and sixth preference

Risktaking: Willingness to try things that

others are afraid to perform easily and with a

high element of uncertainty.

Positive Reciprocity: The willingness to give

back to others after receiving help from them

is high.

Negative Reciprocity: There is little

willingness to reciprocate after receiving help

from others.

Altruism. Altruism: an act of selflessness, i.e.,

concern for the welfare of others.

Trust. A strong belief in the reliability,

truthfulness, competence, or power of someone or

something.

2

2.3 Penn World Tables

The Penn World Tables abbreviated as PWT is a

database containing information on the relative levels

of income, output, inputs and productivity, covering

183 countries from 1950 to 2019. These datasets

initially had only national economic data to measure

real GDP for different countries and different regions.

after continuous expansion, the economic indicators

were gradually updated to include basic information

on countries and years for data on capital,

productivity, and population. The coverage varies in

terms of countries and periods, economic sectors

included and indicators available. Thus, these

databases can be used to answer different types of

questions about the productivity performance of

countries. Because of the desire to study the

relationship between culture, preferences and

economic variables, we decided to introduce some

data from Penn World Tables as dependent variables,

they are: log income (at purchasing power parity) per

worker and log total factor productivity in 2019,

which are used to represent the income level and

productivity level of workers in different countries. It

is worth mentioning that total factor productivity is

the efficiency of production activities over time and

is considered as an indicator of scientific and

technological progress, and its sources include

technological progress, organizational innovation,

specialization and production innovation.

Here, if we want income per worker data, we need

to set the desired year in the Penn World Tables

dataset: for example, 2019, ISO country code. The

key points to focus on are Expenditure-side real GDP

at chained PPPs (in mil. 2019US dollar), abbreviated

as ‘rgdpe’ and Number of persons engaged (in

millions), abbreviated as ‘emp’. The abbreviation is

definitions come from Wikipedia

Culture, Economic Preference and Economic Development with Python: Evidence from Two New Datasets

857

‘emp’. As we know, we can get the wage per worker

by dividing the real GDP on the expenditure side of

the PPP by the total number of workers. If we need

data for total factor productivity, we need the specific

year (year) in the PWT dataset: 2019, the ISO country

code, and ‘ctfp’,which means total factor produc-

tivity level at current purchasing power parity, in

order to make the variance of the dependent variable

more constant as the independent variable increases,

we choose to multiply the overall data by the

logarithm to obtain Log Income Per Worker and Log

Total Factor Productivity.

3 STYLYZED FACTS

3.1 Correlation between Different

Culture and Preference Measures

After collecting data from both the Geert Hofstede

Six-Dimensional Culture Index data set and the

Gallop Global Preference Survey, we learned that

both use the ISO country code, a set of abbreviations

or symbols used to identify countries, so we com-

bined the two data sets using this feature of the

country code. Obviously, we obtained a data set of

cultural dimension indices and economic preferences

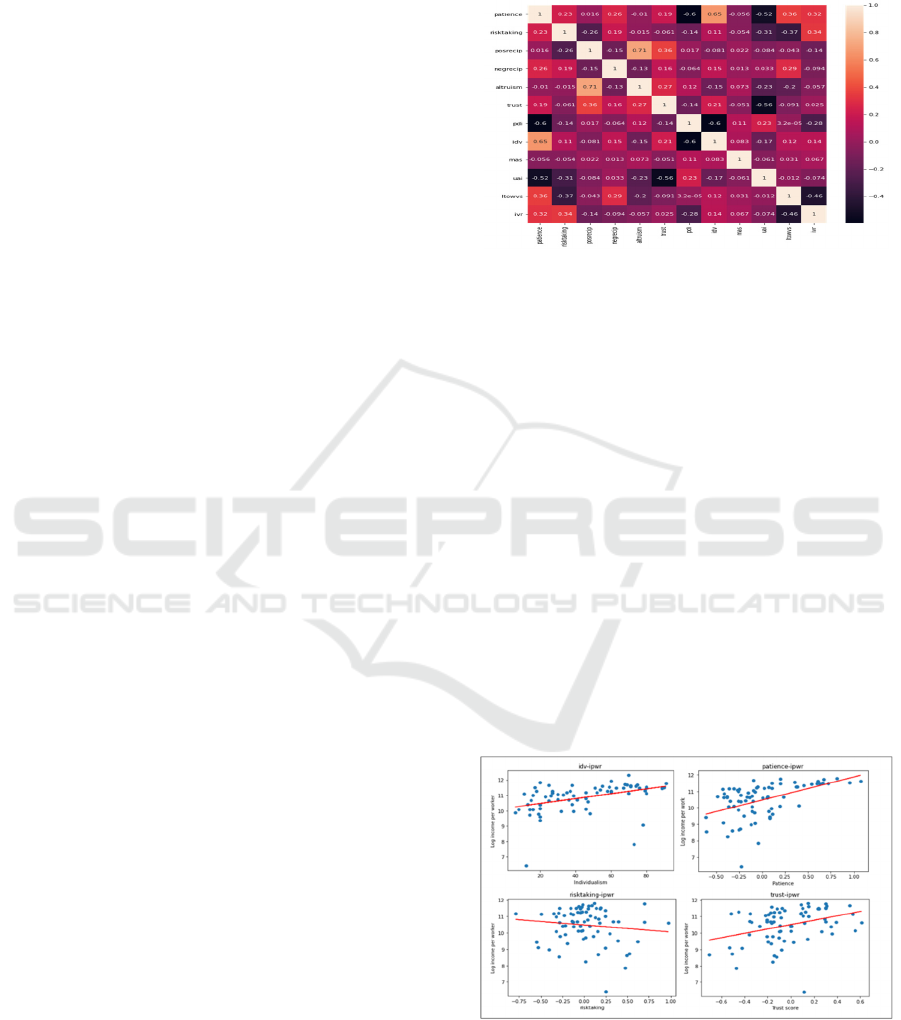

for 73 countries. In addition, we produced a

correlation coefficient matrix and heat map of the two

in Figure 1. That is, the correlation coefficient

between any two variables is used to see if there is an

interesting association between culture and a

particular preference. The closer the value in the heat

map is to 1, the stronger the correlation between the

two; the closer the value is to -1, the stronger the

negative correlation; and the correlation between the

two is close to 0, indicating no research potential. We

can clearly see that these characteristics are

undoubtedly the most relevant to” themselves We

don't need this result, because individualism has been

shown to influence specific economic outcomes in

previous studies, we first focus on the simple

correlations between individualism and other

economic preferences/cultural dimensions. As can be

seen from the figure, individualism has a strong

correlation with patience with a value of 0.65,

followed by trust with a value of 0.21, while other

characteristics also show positive correlations, but

with little significance. The finding between patience

and individualism is very interesting, so in the case of

3

The paper uses scatter plots of individualism, patience,

risk-taking, and trust as representative images of the four

a strong correlation we must pay attention to whether

patience also affects economic outcomes. The highest

positive correlation with patience can be found in the

heat map where the cultural and preference factor is

long-term orientation, with a correlation value of

0.36, followed by indulgence and restraint with a

value of 0.32. When trying to filter cultural

characteristics and preferences that have research

potential by setting the criteria for a positive

correlation with individualism and patience higher

than 0.1, we obtain several values with criteria that

are met. They are:

Trust: its correlations with individualism and

patience were 0.21 and 0.19 respectively.

Long-term orientation: its correlation with

individualism is relatively small at 0.12, but its

correlation with patience is slightly higher

with a value of 0.36;

Indulgence and restraint: its correlations with

both are 0.14 and 0.32;

Negative reciprocity: its correlations are 0.15

and 0.26, respectively;

Risk-taking: its correlation with individualism

is 0.11 and correlation with patience is 0.23.

3.2 Correlation between Cultural

/Preference Measures and

Economic Outcomes

After becoming familiar with some basic correlations,

it is more intuitive to use a scatter plot to represent

the correlation between the independent and

dependent variables. We made a scatter plot

3

between individualism and log income per worker

and log total factor productivity, which can be clearly

seen to be roughly similar to the image in the original

article Gorodnichenko and Roland (2017). Thus, we

can determine that our research is in the right

direction. Next, we need to verify the degree of

correlation of cultural and economic preferences that

may affect economic outcomes.

By plotting the images, we visualize the positive

and negative situation and the degree of correlation

between the independent and dependent variables.

We broadly divided the cultural and economic

preferences into four study sections based on this

criterion. These are (1) individualism and power

distance. (2) patience and longterm orientation versus

short-term orientation. (3) risk-taking attitude. (4)

social preference. In addition to these three

dimensions, we found other characteristics that would

research directions of cultural and economic preferences

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

858

positively affect economic outcomes. They are trust,

positive reciprocity and negative reciprocity.

Obviously, whether a person is willing to trust others

in economic activities and whether a person is willing

to give back after receiving help from others are

personal preferences in social life. Therefore, we

decided to classify trust, positive reciprocity and

negative reciprocity as social preferences in this

paper.

Individualism and Power distance: The scatter

plot between individualism and income per

worker/total factor productivity indeed shows

that workers have higher income levels and

have higher total factor productivity in

countries with a strong individualistic spirit.

In addition, power distance in the plot

indicates that it can result in strong negative

influences on economic effects.

Patience and Long-term Orientation: By

plotting the patience/long-term orientation

scatter plot, we find that patience and

individualism have a stronger impact on

economic outcomes, while long-term

orientation also unsurprisingly affects

workers' income and has a positive but small

impact on total factor productivity.

Risk Attitude: By plotting a scatter plot of

risk-taking and income per worker/total factor

productivity, we find that more adventurism

leads to lower worker incomes and total factor

productivity, which is contrary to our original

conjecture.

Social Preference: The relationship between

individualism and trust has been discussed in

the literature of Gorodnichenko and Roland

(2017). In addition, they have concluded that

there is a positive but not a strong relationship

between the economic outcome of employees'

income and trust. In the heat map, the

correlation between positive reciprocity and

individualism is -0.081 and the correlation

with patience is 0.016. Although the cor-

relation is not strong, the scatter plot shows

that it strongly affects the income level of

workers, indicating that the higher the trust,

the higher the income level of workers in the

country. In the scatter plot, it shows that trust

positively affects total factor productivity. As

well as both positive and negative reciprocity

positively affects workers’ income and total

factor productivity, the reasons for the effect

are worth further discussion.

4 EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

We use the original data from our references to

reproduce their findings. Unfortunately, although we

use the data of the culture dimension from Geert

Hofstede's website, after combining it with the PWT

data (i.e., the data set with income per worker/total

factor productivity) and removing the undefined or

unrepresentable values, we only get 72 observations

of income per worker, and we can't get 96

observations from the original data. This is probably

due to the fact that the original paper used Penn

World Tables version 6.3 to obtain income per

worker data for the year 2000, and we used Penn

World Table version 10.0 to obtain income per

worker data for the year 2019, with some changes in

the countries and ways of data collection as the years

progressed. The estimated value of the explanatory

variable parameter in the one-dimensional linear

regression model of individualism and income per

worker built in the original paper is 0.030, and the

correlation coefficient in our replicated regression

results is 0.0158, which approximates 0.016 and also

yields a relatively significant result.

In the original paper, researchers used total factor

productivity data from Hall and Jones (1999), we use

data from Penn World Table version 10.0 on TFP

levels for different countries in 2019 at current

purchasing power parity. Our sample of observations

is also smaller than the original literature with 77

observations, the number is 66. It is difficult to

determine the exact difference between the two data

sets because of the different sources, years and

methods of data collection. In the original article, the

correlation coefficient between individualism and log

total factor productivity from Hall and Jones (1999)

was 0.013, and in our regression results the regression

coefficient was 0.003, again yielding relatively

significant results.

Next, we can start doing the same linear analysis

with the variables we are concerned with. The results

are as follows.

4.1 Regression Framework

LIPWRi= a + βCULi +ϵ

(1)

where LIPWR is the log income per worker of

country i, and CUL represents the particular cultural

variable used as the explanatory variable that varies

across questions.

The regression results are reported in Table 1.

LCTFPi = a + β CULi +ϵ

(2)

where LCTFP is the log total factor productivity of

country i, and CUL represents the particular cultural

Culture, Economic Preference and Economic Development with Python: Evidence from Two New Datasets

859

variable used as the explanatory variable that varies

across questions.

The regression results are reported in Table 2.

4.2 Individualism and Power Distance

Tables 1 and 2 present OLS estimates of the basic

specification, with the dependent variables being log

income per worker and total factor productivity. The

regression coefficient between individualism and

income per worker in the first column is 0.016. The

specific implication is that for every 1-unit increase

in individualism, the log income per worker increase

by 1.6 percent. Since this model is estimated from

crosssectional data, the R2 value is relatively low,

which implies that the fit is also low. In the paper on

Culture, Institutions And National Wealth

Gorodnichenko and Roland (2017), the regression

coefficient of individualism on log income per

worker is 0.030, which is a more significant effect.

The difference in the data may be due to fewer

observations in our data, as well as other influencing

factors. In contrast to the former, the regression

coefficient of individualism on total factor

productivity is 0.003, and the coefficient, although

positive, is insignificant.

In the second column, power distance has a

negative effect on two economic outcomes, income

per worker and total factor productivity. The basic

implication of the regression coefficient is that for

every 1 unit increase in power distance, the log

income per worker decreases by 1.7 percent and total

factor productivity decreases by 0.4 percent. We can

explain this phenomenon by real examples. For

instance, countries with lower power distance have

less hierarchical differences between people, focus on

solidarity and pay more attention to each individual's

ability. Conversely, the greater the power distance,

the more rigid the hierarchy may be, which can have

a negative impact on economic outcomes.

4.3 Patience and Long-Term

Orientation

The correlation coefficient between patience and log

income per worker in the fourth column is 1.401, and

the correlation with total factor productivity is 0.239.

This means that for every 1 unit increase in patience,

log income per worker increase by 140.1 percent,

while at the same time total factor productivity

increases by 23.9 percent. This reflects the fact that

cultural traits may have a significant impact on

economic outcomes, especially qualities like patience

that may increase efficiency and reduce mistakes. But

long-term orientations, which are also excellent at

improving work precision, don't have as large a

positive impact as patience. For each unit increase in

the long-term orientation in the third column, the log

income per worker increases by 1.4 percent. The

effect of long-term orientation on total factor

productivity is 0.

4.4 Risk Attitude

In the sixth column, the coefficient on risk-taking is -

0.428. It indicates that for every 1 unit increase in

risk-taking, the log income per worker decreases by

42.8 percent. In the regression table with total factor

productivity as the dependent variable, the coefficient

on risk-taking is -0.012, indicating that for every 1

unit increase in risk-taking, total factor productivity

decreases by 1.2 percent. Obviously, in countries

with risk-taking spirit, in such a social atmosphere,

there may be an influx of risk-takers, but this also

largely increases the chances of people making

mistakes and bad decisions at work, and the

probability of making bad economic decisions in the

national government sector increases. For example,

the Argentine government made it illegal for the

Central Bank to print money and had to rely on

foreign debt to increase its currency reserves, leading

to the devaluation of the Argentine currency. The

resulting negative impact is directly reflected in the

income level of the population. It also gradually

makes the level of output that can be obtained from

the input factors of production gradually decrease.

4.5 Social Preference

The trust located in the fifth column increases the log

income per worker by 133 percent and total factor

productivity by 23.8 percent for every 1 unit increase.

This means that the regression coefficients between

the independent and dependent variables are 1.330

and 0.238, respectively. The other two social

preferences are positive reciprocity and negative

reciprocity, which are located in the seventh and

eighth columns, respectively. Both of these two

preference independent variables have a significant

effect on log income and total factor productivity per

worker. For each unit increase in positive reciprocity,

log income increases by 50.8 percent, and for each

unit increase in negative reciprocity, log income

increases by 119.1 percent. The effects for total factor

productivity are 13.2 percent and 10.3 percent,

respectively.

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

860

4.6 Robustness of the Findings

This thesis is the result of an in-depth study based on

some of the results of previous studies, so it is

important to verify the accuracy of the reference

data to ensure the smooth implementation of the

next study. In addition, the regression framework of

this paper is too simple due to the lack of instrumental

and control variables, which also can't guarantee the

accuracy of the study results to be very high. The only

way to clarify the causal relationship in the

experiment is to use control variables to control

variables other than the independent variable that can

cause changes in the dependent variable. After

solving the complex endogeneity problem with

instrumental variables, it is possible to make the

obtained results as close to the real results as possible.

We should control for the different continental

geographic locations, cultural differences caused by

immigration and differences in preferences used in

the papers that are closely followed in this

thesisGorodnichenko and Roland (2017).

We need to control other determinants of

economic growth, including institutions, human

capital, legal sources, ethnic divisions, gender, age,

and so on. Only in this way can the article be more

convincing.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Based on the fact that individualism affects income

and productivity, we found that individualism, power

distance, long-term orientation, patience, trust, and

positive/negative reciprocity all positively or

negatively affect each worker's income and total

factor productivity.

Despite these conclusions, there are some

shortcomings in the article. Introducing more

dependent variables would make the conclusion that

cultural characteristics affect economic outcomes

more convincing. In addition, the paper doesn't

invoke instrumental variables to address the

endogeneity between cultural characteristics and

dependent variables. Because the relationship

between culture and economy is very complex, it is

difficult for us to find exogenous variables that affect

the endogenous variables. We hope that this paper

will lead to a better understanding of the impact of

cultural dimensions and preference characteristics on

the economy and raise the importance of cultural

characteristics when studying economic outcomes.

6 FIGURES AND TABLES

6.1 Heat Map

Figure 1: Correlation between different cultural and

preference measures

Notes. — Source: cultural economic data comes

from Geert Hofstede's Six-dimensional Cultural Index

and Global Preferences Survey. Idv is Hofstede's

index of Individualism. pdi is Hofstede's index of

Power Distance. Ltowvs is Hofstede's index of Long-

term Orientation. posrecip is The Global Preference

Survey's a preference measure of Positive

Reciprocity. negrecip is The Global Preference

Survey's a preference measure of Negative

Reciprocity. Mas is The Global Preference Survey's a

preference measure of Masculinity. uai is The Global

Preference Survey's a preference measure of

Uncertainty Avoidance. Ivr is The Global Preference

Survey's a preference measure of Indulgence vs.

Restraint.

6.2 Scatter Plot

(a) Log Income Per Worker

a. Notes.— Source: cultural economic data comes

from Geert Hofstede's Six-dimensional Cultural

Index and Global Preferences Survey. idv is Hofstede

Culture, Economic Preference and Economic Development with Python: Evidence from Two New Datasets

861

’ s index of Individualism. patience is The Global

Preference Survey ’ s a preference measure of

Patience. trust is The Global Preference Survey’s a

preference measure of Trust. risktaking is The Global

Preference Survey’s a preference measure of Risk-

taking. ipwr is log income per worker in 2019 from

the Penn World Tables. idv-ipwr means the

relationship between Individualism and Income per

Worker. patience-ipwr means the relationship

between Patience and Income per Worker. risktaking-

ipwr means the relationship between Risk-taking and

Income per Worker. trust-ipwr means the relationship

between Trust and Income per Worker.

(b) Log Total Factor Productivity

b. Notes.—Source: cultural economic data comes

from Geert Hofstede's Six-dimensional Cultural Index

and Global Preferences Survey. idv is Hofstede’s

index of Individualism. patience is The Global

Preference Survey’s a preference measure of Patience.

trust is The Global Preference Survey’s a preference

measure of Trust. risktaking is The Global Preference

Survey’s a preference measure of Risk-taking. ctfp is

log total factor productivity in 2019 from the Penn

World Tables. idv-ipwr means the relationship

between Individualism and Income per Worker.

patience-ipwr means the relationship between

Patience and Income per Worker. risktaking-ipwr

means the relationship between Risk-taking and

Income per Worker. trust-ipwr means the relationship

between Trust and Income per Worker.

6.3 Table

Table 1: Cultural/preferential characteristics and log

income per worker.

Notes.—Source: The dependent variable is log

income per worker in 2019 from the Penn World

Tables. idv is Hofstede's index of Individualism. pdi

is Hofstede's index of Power Distance. ltowvs is

Hofstede's index of Long-term Orientation. patience

is a preference measure collected by The Global

Preference Survey. Trust is a preference measure

collected by The Global Preference Survey. rksk is

The Global Preference Survey's a preference measure

of Risk-taking. posrecip is The Global Preference

Survey's a preference measure of Positive

Reciprocity. negrecip is The Global Preference

Survey's a preference measure of Negative

Reciprocity.

Table 2: cultural/preferential characteristics and log total factor productivity

BDEDM 2022 - The International Conference on Big Data Economy and Digital Management

862

b.Notes.—Source: The dependent variable is log

total factor productivity in 2019 from the Penn World

Tables. idv is Hofstede's index of Individualism. pdi

is Hofstede's index of Power Distance. ltowvs is

Hofstede's index of Long-term Orientation. patience

is a preference measure collected by The Global

Preference Survey. Trust is a preference measure

collected by The Global Preference Survey. rksk is

The Global Preference Survey's a preference measure

of Risk-taking. posrecip is The Global Preference

Survey's a preference measure of Positive

Reciprocity. negrecip is The Global Preference

Survey's a preference measure of Negative

Reciprocity.

REFERENCES

Algan, Y. and Cahuc, P. (2007). Social attitudes and

macroeconomic performance: An epidemiological

approach. Technical report, Mimeo, University of Paris

1.

Acemoglu, D. and Johnson, S. (2005). Unbundling

institutions. Journal of political Economy, 113(5):949–

995.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. A. (2002).

Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the

making of the modern world income distribution. The

Quarterly journal of economics, 117(4):1231–1294.

Ashraf, Q. and Galor, O. (2012). The “out of africa”

hypothesis, human genetic diversity, and comparative

economic development.

Birchenall, J. A. (2014). Disease and diversity in africa’s

long-term economic development. Technical report,

Technical report, University of California Santa

Barbara.

Brock, G. and Brighouse, H. (2006). The political

philosophy.

Bisin, A. and Verdier, T. (2001). The economics of cultural

transmission and the dynamics of preferences. Journal

of Economic theory, 97(2):298–319.

Chen, M. K. (2013). The effect of language on economic

behavior: Evidence from savings rates, health

behaviors, and retirement assets. American Economic

Review, 103(2):690–731.

Doepke, M. and Zilibotti, F. (2014). Culture,

entrepreneurship, and growth. In Handbook of

economic growth, volume 2, pages 1–48. Elsevier.

Fern´andez, R. and Fogli, A. (2009). Culture: An empirical

investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. American

economic journal: Macroeconomics, 1(1):146–77.

Falk, A., Becker, A., Dohmen, T., Enke, B., Huffman, D.,

and Sunde, U. (2018). Global evidence on economic

preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

133(4):1645–1692.

Gorodnichenko, Y. and Roland, G. (2017). Culture,

institutions, and the wealth of nations. Review of

Economics and Statistics, 99(3):402–416.

Granovetter, M. (2005). The impact of social structure on

economic outcomes. Journal of economic perspectives,

19(1):33–50. R. Nicole, “Title of paper with only first

word capitalized,” J. Name Stand. Abbrev., in press.

Greif, A. (1994). Cultural beliefs and the organization of

society: A historical and theoretical reflection on

collectivist and individualist societies. Journal of

political economy, 102(5):912–950.

Greenwood, J., Seshadri, A., and Yorukoglu, M. (2005).

Engines of liberation. The Review of Economic

Studies, 72(1):109–133.

Granovetter, M. (2005). The impact of social structure on

economic outcomes. Journal of economic perspectives,

19(1):33–50.

Greenwood, J. and Guner, N. (2010). Social change: The

sexual revolution. International Economic Review,

51(4):893–923.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing

values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across

nations. Sage publications. M. Young, The Technical

Writer's Handbook. Mill Valley, CA: University

Science, 1989.

Hall, R. E. and Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries

produce so much more output per worker than others?

The quarterly journal of economics, 114(1):83–116.

Hall, R. E. and Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries

produce so much more output per worker than others?

The quarterly journal of economics, 114(1):83–116.

Lucas Jr, R. E. and Moll, B. (2014). Knowledge growth and

the allocation of time. Journal of Political Economy,

122(1): 1–51.

Tabellini, G. (2010). Culture and institutions: economic

development in the regions of europe. Journal of the

European Economic association, 8(4):677–716.

Tertilt, M. (2005). Polygyny, fertility, and savings. Journal

of Political Economy, 113(6):1341–1371.

Culture, Economic Preference and Economic Development with Python: Evidence from Two New Datasets

863