Best Practice in Multi-organisation Sensitive Health Data Sharing:

A Comparative Analysis of Ireland’s Data Governance Approach

for the Covid–19 Data Research Hub

Aleksandra Czarnik

1a

, Aoife Darragh

1b

, Maria Hurley

1

, Daniel O’Connell

1c

, Michele Quagliata

1

and Rob Brennan

2d

1

School of Computing & School of Law and Government, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland

2

ADAPT Centre, School of Computing, Dublin City University, Dublin 9, Ireland

daniel.oconnell245@mail.dcu.ie, michele.quagliata2@mail.dcu.ie, rob.brennan@dcu.ie

Keywords: Data Governance, Health Data, Data Security, Health Research, Public Administrative Bodies.

Abstract: This paper examines, from a data governance perspective, the creation and operation of the Irish Covid–19

Data Research Hub, a secure multi-institution collation and access-controlled source of sensitive Covid–19

epidemiological data from diverse sources. The Hub is assessed alongside international comparators and with

reference to a set of leading academic data governance models, including those developed by Khatri & Brown

(2010), Winter & Davidson (2019), and Abraham et al (2019). The analysis explores the requirements for

such data hubs balancing data protection, security, and health policy decision making. It examines the data

hub design from architectural, data access policy, and data governance perspectives. Whilst recognising

certain unique features of the Covid–19 Data Research Hub not replicated elsewhere, it highlights key data

governance strengths and gaps in the model used which may inform future development of similar hubs

supporting the exploitation of public sector data for health policy-related research. The interdisciplinary legal

and technical data governance assessment methodology described here is applicable to the increasing number

of data federation and aggregation projects increasingly being deployed in both public and private healthcare

settings.

1 INTRODUCTION

Health research operates in one of the most sensitive

of all data domains (General Data Protection

Regulation, 2018) and requires exemplary standards

of data stewardship and governance to comply with

data protection laws and to maintain public

confidence. The Data Administration Management

Association (DAMA, 2017) defines data governance

as “the exercise of authority, control, and shared-

decision making (planning, monitoring, and

enforcement) over the management of data assets”. In

addition, ethical health data governance, as described

by Hripcsak et al. 2014, must involve the structured

management, secure storage and controlled

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6217-5701

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3104-2767

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8641-2409

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8236-362X

disclosure of health data only to appropriate users, to

ensure knowledgeable and proper use of the data.

This challenge of providing secure researcher

access to sensitive health data is well recognised

internationally and the last decade in particular has

seen significant State led initiatives to develop

structurally, legally and ethically robust systems to

exploit the explosion of opportunities, including via

Big Data, in this sphere of public health

administrative data. Examples include initiatives in

the UK, (Winter & Davidson, 2018), France

(Goldberg & Zins, 2021) and Germany, (Cuggia &

Combes, 2019). Ireland lags in the development of

the infrastructure and services required to deliver

such an environment. Hence it is relevant to evaluate

Czarnik, A., Darragh, A., Hurley, M., O’Connell, D., Quagliata, M. and Brennan, R.

Best Practice in Multi-organisation Sensitive Health Data Sharing: A Comparative Analysis of Ireland’s Data Governance Approach for the Covid–19 Data Research Hub.

DOI: 10.5220/0010802100003123

In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2022) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 57-68

ISBN: 978-989-758-552-4; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

57

the Irish Covid-19 Health Research Data Hub jointly

developed by the Central Statistics Office,

Department of Health and Heath Research Board

against international best practice. Even defining the

terms of this comparison is challenging, due to the

diversity of national health data sharing projects.

Important related developments in academic

research on models of Data Governance (Khatri &

Brown, 2010; Winter and Davidson., Abrahams et al,

2019) have emerged which reflect best practice in the

design, build and operation of any large scale data

management system. Taken together, information

from the foregoing practical and theoretical systems

can be used to benchmark the Covid–19 Data

Research Hub in terms of data governance and to

identify strengths, gaps and opportunities for future

such initiatives by the Irish public administration.

In this paper, we investigate the research question

“to what extent can international health data sharing

hubs and academic data governance frameworks be

used to evaluate data governance in the Covid–19

Data Research Hub?”. We use this question to

conduct an analysis of data governance best practice

in the sphere of public administrative health data

access, analysis and exploitation and we show how to

evaluate the Irish approach based on comparison with

international approaches and academic models.

The contribution of this paper is by drawing on the

learnings from these models, we propose a series of

areas for focus both in the future development of the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub and for other public

administrative health data hubs and we discuss the

applicability of academic data governance models to

these. Using the Covid–19 Data Research Hub as its

model, this case study aims to illustrate a method to

critically assess the state of the art in the collation and

dissemination for statistical purposes of public sector

health research data, specifically focusing on data

protection, data governance and access control. It will

examine the requirement for this approach; the aims

of the model; the involvement of inter-organisational

collaboration and the legal and governance structures

used in its construction. The key strengths and

weaknesses of the Covid–19 Data Research Hub are

be outlined and options for alternative approaches

will be identified.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 discussed related work, section 3 discusses

our case study consisting of a description of the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub, our evaluation

methodology and the evaluation itself, section 4

discusses our findings and section provides our

conclusions.

2 RELATED WORK

Any attempt to examine the data analysis approach of

public administrations in responding to the Covid–19

pandemic requires an understanding of both academic

and deployed models addressing intra and inter-

organisational data governance and exploitation of

administrative and Big Data in the healthcare related

sphere (Tse et al, 2018). This section examines the

existing literature in large scale data governance

generally across multiple organisations, particularly

from the health data hub perspective, seeking out

existing data hubs of similar nature, considering the

impacts of Big Data on research, and finally, the

evaluating impact of the use of such data sets on the

organisation and exploitation of state data resources

looking forward.

Due to the emergent nature of the data governance

domain, research on data governance with a multi-

organisational perspective in the area of health data is

still very limited. There is a pattern of literature

reviews considering the issue of data governance in

relation with health data hubs, but few papers address

it directly. One paper (Nielsen, 2017) directly notes

that within data governance published between 2007

and 2017, there have been only 62 papers directly

fitting under the description of ‘data governance’ i.e.,

not confusing data governance with data

management. Within those papers, only 11% consider

e-health, and only 3% consider e-government. This

highlights a gap in literature, as academic surveys

show that persons are generally positive about sharing

their data for research purposes (Nielsen, 2017), with

their top priorities revolving around secure databases,

data stewardship, and anonymisation or

pseudonymisation, as well as re-consent. Addressing

these concerns requires strong data governance.

2.1 Healthcare Data and Data

Governance

Only recently has the potential of Big Data in

healthcare, particularly from a research perspective,

begun to be systematically explored and exploited. In

this regard, (Wang et al., 2018) identify five discrete

areas in which Big Data analytics can enhance

healthcare activities, these being analytical capability

for patterns of care, unstructured data analytical

capability, decision support capability, predictive

capability, and traceability. Literature also points to

the fact that there is increasing public and academic

perceptions of Big Data being of substantial value for

improving decision making processes, education,

healthcare, law, social media and artificial

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

58

intelligence. Comparatively, there has not been as

much focus on the governance of said data though,

unless dealing with the risks of artificial intelligence

(Ethics Guidelines on Trustworthy AI, 2019).

Literature is also lacking in respect of data

governance of Big Data for research purposes,

particularly dealing with ‘sensitive’ data. It also often

conflates data management and data governance, or

in some cases calls for better techniques to handle

data, while omitting, or perhaps ignoring, data

governance. Yet this omission is problematic given

the related significance of the legal, digital trust, and

societal implications. Consideration is needed of data

governance by design, data interoperability, data

quality, data storage and operations, data security,

and data architecture.

2.2 National Data Hub Initiatives

Few national administrations have utilised health data

hubs within Healthcare (e-Estonia, 2021) and the area

remains emergent. The nature of health research is

such that in many instances the greatest value is to be

exploited where multiple data flows are combined to

bring new insights. As such, collaboration between

these entities requires complex inter-organisational

data governance (Lis & Otto, 2020).

Two interesting but different approaches are

explored from France and Germany by Cuggia and

Combes (2019), who examine the respective top-

down and bottom-up approaches to developing

publicly funded health data hubs in these countries. In

France, the Health Data Hub was designed to operate

on a hub and spoke model, with the central delivery

of sophisticated data sharing infrastructure supported

by highly expert staff in all relevant technical

domains, including IT, engineering, medicine, law

and governance. In this Top-Down model, projects

were then selected to be incorporated into the data

sharing infrastructure in two groups - one involving

only public or academic collaborators, the other

offering access also to industry partners. In Germany,

the Medical Informatics Initiative was developed

using a Bottom-Up methodology, reflecting the

federal structure of that country’s public

administration, with locally developed Data

Integration Centres and locally promoted use cases,

building on existing regional (Land) based e-health

strategies. The most successful of these use cases

were then selected to graduate to a subsequent phase

of work, during which the respective projects are to

be grown and networked. The German model focuses

on the importance of encouraging stakeholder

confidence in health data sharing, with strong

electronic consent declarations, trusted third party

technologies for identity management, clearly

defined data rules and access structures, an emphasis

on semantic interoperability, data sharing modalities

and audit criteria. The paper does not reach a

definitive conclusion as to which approach, Top

Down or Bottom Up is the most appropriate, but gives

a clear indication that in both respects the key criteria

include the drive for interoperability, data quality and

citizen involvement and trust dynamics.

Literature within the framework of public

administrative bodies collaborating to create data

hubs also shows great discontinuity though, as there

has been an increase of jointly created networks, and

data collections, in which public administrative

bodies collaborate to construct. However, the same

literature generally does not consider the

collaboration of administrative bodies for the

purposes of research-based datasets, and particularly

the impact that their collaboration may have in the

creation of them.

Estonia (McBride et al. , 2018) is widely

recognised as leader as regards the overall digitisation

of the delivery of government services and its

approach to digital state service delivery, including in

the healthcare sphere, although it does not

specifically inform the instant issue of public health

research responses in a time of pandemic. Therefore

while the technological design and data governance

protections inherent in its model were ground-

breaking and radical in the 1990s when their project

commenced, their application to the present problem

turns less on specific issues of access to health

research data and more on the Estonian State’s

approach to designing digital government on the basis

of a common national commitment to the use of Base

Registries for the collection, use and re-use of citizen

data; a very robust identity verification and

management infrastructure, underpinned by (Public

Key Infrastructure) PKI based authentication and

digital signatures and a transparent “service layer” via

which all Estonians can both access all State services

and view who in the State sector has accessed their

personal data, for what purpose with a full access

audit trail. This model offers possible indicators of a

route map to sustaining public trust in the use and re-

use of personal health information in Ireland, post

pandemic.

2.3 Data Governance Models

Managing the inter-organisational dynamics of data

governance in Big Data research is also a theme in

research by (Lis & Otto, 2020), who define the

Best Practice in Multi-organisation Sensitive Health Data Sharing: A Comparative Analysis of Ireland’s Data Governance Approach for the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub

59

characteristics of interorganisational data governance

around the themes of scope, purpose, goals, roles and

organisation, modes and governance and distinguish

between the more traditional intra-organisational data

governance tasks of assigning decision rights and

accountabilities and the more complex challenges of

inter-organisational data governance, which

frequently involves platform based technical

infrastructures.

An interesting model for approaching data

governance in the specific case of personal health

information is set out by (Winter and Davidson,

2019), who explore Helen Nissenbaum’s approach to

privacy (2009). She describes privacy not as a right to

secrecy or control but as an appropriate flow of

personal information within particular social

contexts. In the Winter and Davidson model (2018),

Data Governance in the area of Personal Health

Information (PHI) should be governed based around

five analytical dimensions – the data domain; the

stakeholders, the value or the application of the PHI,

the governance goal and the governance forum. This

paper explores the particular use case of the Royal

Free Trust and Alphabet’s DeepMind Health

initiative and highlights conflicts between the

partners in respect of key aspects in particular of the

governance goals, governance forms and the value

achieved through the initiative.

Khatri and Brown (2010) is considered the

foundational model of modern data governance and

iterates 5 key data decision domains: Data principles,

Data Quality, Meta Data, Data Access, and Data

Lifecycle. Winter and Davidson (2018) further

develop this model in their 2019 paper also

documenting 5 “dimensions” of governance for

Public Health Data, focusing in inter alia on the role

of Stakeholders (incorporating Direct, Indirect and

Public Health System related) and more specifically

calling out the Value or Application of the work,

generally encompassed Khatri and Brown’s Data

Principles (2013), while a composite synthesis of

research papers published by Abrahams et al. in

(2019) reviews 145 research and practitioner papers

in the sphere of data governance generally published

between 2001 and 2019. The latter define a pyramidal

governance structure, in which data, domain and

organisational scope are counterbalanced by

Governance Mechanisms, all framed by

organisational legal and technical “antecedents” pre

data ingestion and influenced by risk management

and performance related “consequences” post hoc.

Taken together, these three studies provide a

comprehensive governance framework via which to

evaluate research data hubs (see Table 1 below).

Based on the foregoing analysis, our study can

seek to fill gaps in the current literature, in particular

as regards connecting Big Data, the State sector,

personal freedoms, research ethics and data

governance. The lack of extensive published

information on multi-organisation health data hubs

suggests a gap where our comparative analysis could

add value. Additionally, the review uncovered that

while there are live medically oriented hubs

internationally which bear some similarities to the

Irish data hub, none of these systems could be said to

identically match the comprehensively centrally

driven model for Health Data Hub. While the German

Medical Informatics Initiative, through its focus on

clearly defined data rules and access structures,

semantic interoperability, data sharing modalities and

audit criteria appears to share the most similarities to

the Irish hub it still does not share the same function

as the Irish hub which is to ultimately provide a

statistically robust, secure and controlled

environment for the statistical analysis of relevant

data sources to inform the Government’s Covid–19

response.

3 CASE STUDY

This case study to critically assess the Covid–19 Data

Research Hub, compares it with similar

administrative data hubs in order to identify any key

strengths and weaknesses. In order to provide a

proper evaluation, given we could not rely solely on

a comparison of international prototypes we had to

look to models such as the five key decision domains

for effective data use proposed by Khatri and Brown

(2010), the conceptual framework proposed by

Winter and Davidson (2018) as well reaching out to

industry professionals who could provide us with

greater insight into the nuances of how the Covid–19

Data Research Hub was developed.

The steps which were necessary to achieve our

research objectives for this case study included the

following:

• Speaking with members of the public

administrative bodies involved in the Covid–

19 Data Research Hub so as to validate or

invalidate some of our own assumptions.

• Establishing the existence of clear data

governance structures specifically regarding

data access.

• Establishing whether international models

such as those outlined above were examined

during the course of the development of the

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

60

Covid–19 Data Research Hub. Identifying

whether the Covid–19 Data Research Hub

may be able to incorporate features of models

abroad

• Identifying whether the Covid–19 Data

Research Hub diverges significantly from

international standards.

3.1 Covid–19 Data Research Hub

The development of the Covid–19 Data Research

Hub has been a novel undertaking in an Irish context,

precipitated by necessity. The Covid–19 Data

Research Hub is defined here as a technical

architecture which enables secure health data sharing

between Irish public administrative bodies and

approved users in a format that is controlled,

accessible and usable. The infrastructure and

underpinning governance approach were modelled on

best international practice, with a particular emphasis

on data confidentiality and strong governance. It

represents a federated governance and data sharing

initiative as following a decision by the Minister for

Health to authorise it, the Central Statistics Office

was given legal authority to process special category

health data under the control of the Department of

Health and the HSE. This was to facilitate secure,

reliable data access to approved researchers and

thereby to facilitate Covid–19 related analysis.

Looking beyond the current emergency period,

population-level data similar to that stored in the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub may also be a valuable

tool, for example, for designing medical management

algorithms and guidelines (Sharma, Borah and

Moses, 2021).

In response to the Covid–19 pandemic the CSO

began receiving research and analysis relevant data

flows from the HSE (Health Service Executive) and

other public bodies. Consequently, the Covid–19

Data Research Hub was created to make Covid–19

relevant datasets compiled by the CSO from diverse

administrative data sources securely available to

researchers via the CSO Researcher Microdata Files

(RMF) process under Section 20(c) of The Statistics

Act, 1993. The use of a RMF process was designed to

implement the possibility for statistical analysis in a

manner that protects the confidentiality of the data

and ensures that such data is only made available for

use for statistical purposes and to a restricted number

of specifically approved researchers. It was

developed after extensive consultation between the

CSO, the Health Research Board (HRB), the

Department of Health (DoH) and the HSE.

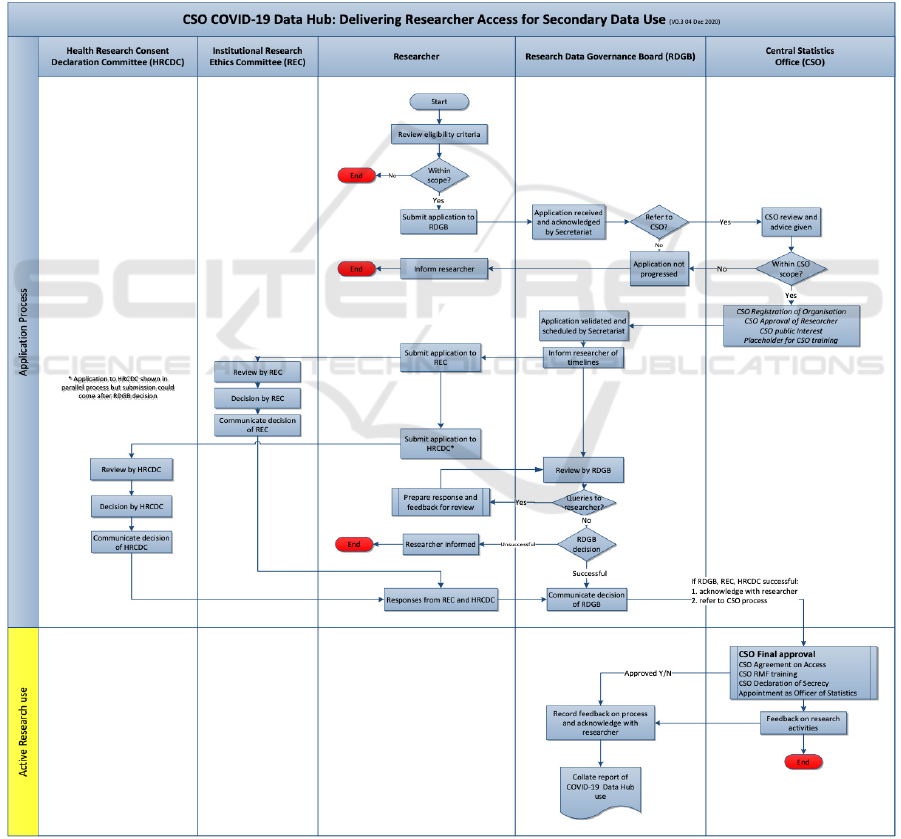

Figure 1: HSE to CSO Health data flows.

From a technical perspective, the process which

transforms data received by the CSO to data available

to the researchers is shown in Figure 1.

HSE and DoH data is transferred by Secure File

Transfer Protocol (SFTP) to a CSO remote server

with the use of encryption and secure transmission

mechanisms from the HSE. Each data flow is dealt

with individually and is stored safely in its original

format in what is called the “Migration Tier” of the

Administrative Data Centre (ADC) of the CSO.

Access to such raw data in the Migration Tier is

confined to a small number of ADC staff for

processing purposes only.

Each entire dataset is then converted from its

original format to a format compatible with the

Statistical Analysis System (SAS) and stored in what

is called the “Source Tier” of the ADC. SAS is the

primary statistical software used by the CSO to

analyse data. Access to such second Tier is limited to

ADC staff for processing and a limited number of

CSO staff with fully documented and approved

reasons which justifies the use of such confidential

data for limited internal or analysis purposes.

Afterwards, a pseudonymised version of each data

flow is also created in SAS and stored in what is

called the Analysis Tier. All access requests for

analysis purposes are with respect to pseudonymised

data only, therefore to this third Tier.

HSE

a21_src: HSE Coronavirus

Assessments, Test Referrals

and Facilities data

C19HospitalCases_src:

Recorded Hospital

Cases as a result of

Covid

–

19

CIDR_src: HSE

Computerised Infectious

Disease Reporting System

HIPE_src: Hospital

Inpatient Discharge Data

NOCA_src: National

Office of Clinical

Audit Intensive Care

Unit Data

SBAR_src: Situation,

Background,

Assessment,

Recommendation,

Shift

handover

data

CCT_src: Covid Care

Tracker Data

Vaccination Info Data:

Record of vaccinations

administered for Covid–19

CSO

Production of

pseudonymised

RMF files

Approval process

Best Practice in Multi-organisation Sensitive Health Data Sharing: A Comparative Analysis of Ireland’s Data Governance Approach for the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub

61

All data flows and datasets involved in the

Migration, Source and Analysis Tiers of ADC are

registered on the internal ADC Data Portal. This

online portal, which uses the CSO intranet, includes a

register of all available data stored, including

metadata and a list of registered users for each data

flow.

Once the data has undergone all the above-

explained processing and is stored in a

pseudonymised form in the Analysis Tier, researchers

may access the RDP via a Citrix connection using

unique credentials. The microdata, at all times,

remains on a CSO server as the RDP is a secure,

locked-down environment from which no data can be

extracted without permission. There is also no

internet/email access and nothing can be copied to the

local PC.

When a researcher has completed work on a file

that they wish to have exported as an output, they may

contact the data custodian in the CSO. Only such

nominated custodians have permissions set to allow

access to the researchers’ inputs and outputs folders

after checking for compliance with statistical

disclosure control.

As declared in the relevant DPIAs by the CSO, the

data will then be retained for as long as necessary to

respond to the pandemic.

Figure 2: Data Access Process Map.

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

62

3.2 Methodology

The Irish model will be evaluated by comparison with

similar administrative data hubs in operation. The

background literature was highly informative in the

describing international comparator data hubs and

four were selected: Health Data Hub (HDH) in France

and the German Medical Informatics Initiative (MII),

the UK’s partnership between the Royal Free Trust

and Alphabet’s DeepMind Health (DMH) AI led

medical data collaboration and the design and

delivery of Estonia’s Digital Government model.

This was complemented by access to the

underpinning DPIA (Data Protection Impact

Assessment) documentation for the Irish Data

Research Hub, which provided a detailed insight into

the design and execution of that model and its

associated governance. This was complimented by an

interview with a key stakeholder (discussed below).

Each of these data hubs have been evaluated in

accordance with their adherence to the data

governance principles and domains laid out in Khatri

and Brown and refined by the 2019 review by

Abrahams et al. This gives a common basis rooted in

best practice to evaluate the current solutions and the

Irish Covid-19 Data Research Hub.

The opportunity of access to a key stakeholder in

the Irish Data Research Hub permitted a more

detailed and nuanced examination of the dynamics

and structures underpinning this initiative. A senior

manager with responsibility for Statistical System

Co-Ordination in the CSO, was interviewed using the

following as a discussion guide. The interview was

semi-structured, intended to provide reliable and

comparable data. Open-ended questions were used to

obtain answers which were not focused on what the

interviewee feels should be utilized within their

organisation, but what is. The interview lasted for an

hour and was transcribed verbatim.

The topics discussed were as follows:

1. Description of objectives of the development of the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub and the interviewee’s

role.

2. Options for project design considered by the

interviewee.

3. Whether or not international exemplars were

examined by the interviewee, and whether any

conclusions were reached if affirmatively answered.

4. The key factors which influenced the final

approach and model for the finalised approach to the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub.

5. Based on international comparators or learnings

since the Covid–19 Data Research Hub has gone live,

the assessment the interviewee would give of the

relative strengths/weaknesses in each model and in

the final Irish model

6. A description of any roadblocks or inhibitors which

forced compromises in design and delivery choices

which were ultimately taken.

7. The steps the interviewee would address in respect

of the aforementioned roadblocks for future

initiatives or learnings which would influence

alternative decision making.

8. General remarks the interviewee would wish to add

in regard to the mechanisms available in Ireland to

leverage administrative data in support of public

policy development.

Together the interview and data governance

evaluation enabled a structured, comparative analysis

of the Covid-19 Data Hub in terms of international

best practice and theoretical soundness.

3.3 Evaluation

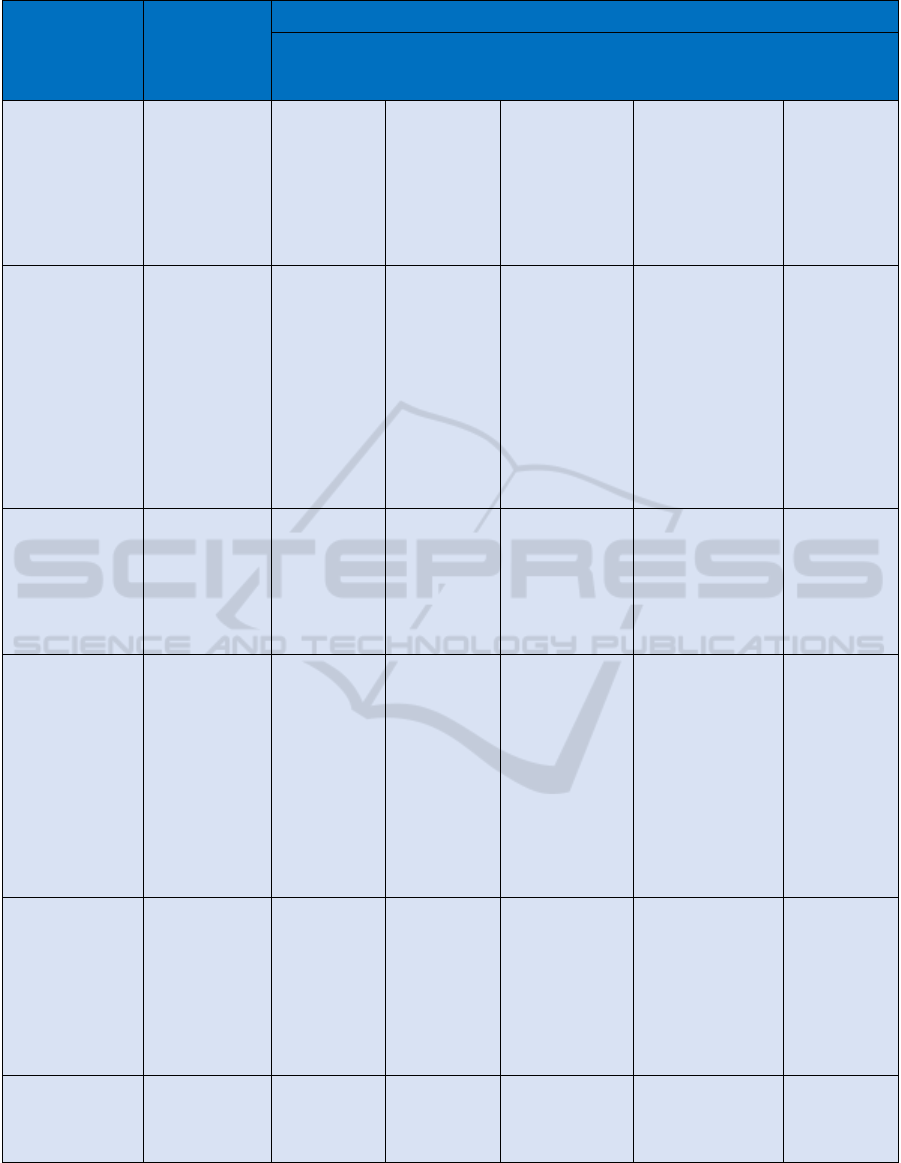

The findings of the evaluation are synthesised in

Table 1 which provides a column for each data hub

assessed and a row for each data governance

dimension following to Khatri and Brown. First we

examine the Irish Covid -19 Data Research Hub in

isolation according to the academic principles of data

governance and then a comparative analysis is

provided with respect to the international models

examined.

The academic Data Governance models evaluated

indicate key strengths in the Irish model (see Table

1), in particular in the data governance areas of Data

Access and Data Principles, however the real value

and application of public health information depends

on the engagement, trust and sustained cooperation of

all stakeholders and there appear to be vulnerabilities

here, especially as regard metadata standards, data

lifecycle management and individual level data

transparency.

The main objective of the Covid–19 Data

Research Hub is to inform decision-making during

the national emergency based on research undertaken

by approved individuals. Pseudonymisation of the

data held on the system protects the privacy of

individuals and international comparison indicates

this to be a standard. However, weak or absent meta

data standardisation is a vulnerability from a Data

Quality and Access perspective and in a longer-term

perspective, in particular for more ordinary-time

purposes, may hinder the value of the data from a

researcher’s perspective.

Governance goals illustrate the objectives

targeted by implementing a governance method. By

robustly governing the data contained in the Covid–

Best Practice in Multi-organisation Sensitive Health Data Sharing: A Comparative Analysis of Ireland’s Data Governance Approach for the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub

63

19 Data Research Hub it is hoped to provide a secure

source for researchers to access pseudonymised data

relating to the Covid–19 pandemic and its effects and,

by extension, to demonstrate the opportunities for

further public sector policy to be informed by parallel

type research.

Governance forms indicate externalities that

impact on achieving the goals set out. These include

organisational units, practices, policies and

regulations and technologies involved in the

management of the data. The CSO ensured that all

necessary protocols under the Statistics Act, the Data

Protection Act/Health Research Regulations were

employed in the collaborative process. The

establishment of the Research Data Governance

Board (RDGB) acts as an added safeguard in

supporting governance and transparency of the

application process for approved researcher status.

Overall, from the perspective of formal or

academic governance, the Irish model presents

opportunities for improvement, on a solid and

verifiable governance base.

From the perspective of practical implementation

of other data hub models, Estonia (see Table 1) has

stolen a march in the digitisation of their public

administrative systems generally. Designed for

broader purposes than the Irish Covid–19 Data

Research Hub, their system allows residents to access

personal health data amongst a range of all the data

they share with the public administrative system,

sharing this data with doctors and healthcare

professionals whilst having full visibility of its use.

This creates ease of engagement for both parties and

removes the need for manual file transfer as it can be

carried out online. Regarding the Irish data hub, this

system operates in a more detached manner, ingesting

information specifically related to instances of

Covid–19, processing it for governance and onward

access purposes, with no option for dynamic sharing

of datasets. Only approved researchers will have

access to the data hub, following an extensive process

involving the HRB, the CSO and the RDGB.

The French Health Data Hub operates on the

principle of encouraging research, much like the Irish

data hub. A key feature of the French HDH is

Artificial Intelligence (AI), which is not yet included

in any aspect of the Irish Covid–19 data hub, although

there are clear opportunities for the deployment of

Machine Learning techniques. The HDH aims to

expand the area of digital health by including multiple

parties in the data sharing system. Similarly, the Irish

Covid–19 Data Research Hub developed with

involvement from a number of public administrative

bodies, collaborating to ensure all bases were covered

regarding the data transfer by the HSE to the CSO,

the application process managed by the HRB and the

system for approvals

Germany has developed a Medical Informatics

Initiative focusing on the promotion of training and

educating among selected healthcare actors but relies

heavily on local cooperation and is as yet unproven at

a national level. The bottom-up nature of its operation

offers assurance at a governance level whilst risking

constraints in terms of broader utility, across its

audience of data scientists, data stewards, doctors,

patients, research and universities. It is hoped that this

data hub will provide insights into medical research

and improve treatment decisions. Access to the Irish

Covid–19 Data Research Hub is limited to approved

researchers, as mentioned above, in a bid to inform

public bodies of evidence to support policy decisions.

3.3.1 Data Hub Stakeholder Interview

Summary

The interviewee noted the objectives were to

encourage research on Covid–19 across a broad group

of researchers, consistent with the Statistics Act 1993

and health research obligations. He noted that a safe

haven for research has been a necessity, which

complied with all law and recognized the status of

health data as ‘special category data’.

Regarding the “state of the art” in data hub design

and execution, it was noted that the Health Research

Board (HRB) is internationally connected and well

aware of international trends in areas relating to

process maps, research ethics, and public interest,

while the CSO is a globally active National Statistical

Institute, operating to transnational standards.

Accordingly, Irish Health Research Regulations and

CSO Statistical Data Governance Standards are

considered state of the art and heavily influenced the

governance model followed by the CSO and the HRB

in developing the data hub.

The interviewee’s principal governance and risk

factors in the Data Research Hub design & architecture

included ethics, consent, public interest, legislation,

metadata and data availability, lack of persistent

identifiers, and consideration of international trends in

data hub creation and management. The interviewee

expressed the view that the data hub was strong in the

area of research ethics and consent, with both heavily

reflected in the model, while noting that the absence of

advance data subject consent could be discounted to

some extent by the public interest imperative of Covid–

19 related responses. Nonetheless, approval to access

such data is given from an independent source, Health

Research Consent Declaration Committee.

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

64

Table 1: Data Hub Evaluation based on Data Governance Domains and Antecedents.

Data Governance Data Hubs

Decision Domain Scope French HDH German MII

Covid–19

Research Data

Hub

DeepMind Health

(UK)

Estonia

Antecedents External (legal,

regulatory,

market

envt…)/Internal

(Business

Strategy; IT

architecture;

Culture envt)

Central rule

setting. Strict

national

regulatory

framework,

Hub and

Spoke

architecture

Bottom-Up

approach

Urgent national

response

Local (Health Trust

to private

contractor)

contracting

arrangement with

weekly specified

contracting

parameters

Clean Sheet –

common

baseline –

Register

based

approach

Data Principles Acceptable

uses? Desirable

behaviours?

Use & re-use

protocols?

Regulatory

Engagement

18 projects

sanctioned,

subject to

independent

oversight.

Complex

access/match

ing processes

slowing

progress.

Moving to

harmonise

Strong

commitment

to

interoperabili

ty and data

sharing

Tightly defined,

purpose

dependent

access. no open

sharing

protocols.

rigorous output

checking. close

DPC

engagement

Weakly defined.

Large data dumps

with poorly

specified outputs.

Data principles

severely criticised

according to an

Independent

Review Panel in

2017

Collect once,

use often is

the guiding

principle with

strict national

governance re

access and

use.

Maximum

transparency

Data Quality/

Domain Scope

Accuracy,

Timeliness,

Completeness,

Credibility

No evidence

of validation

No evidence

of validation

Acknowledge

unvalidated

No evidence of

validation

100%

transparent,

data viewable

by data

subject,

editable/verifi

able

Metadata/

Domain Scope

Semantic

Dictionary

Metadata

Maintenance

Implied

strong

governance,

given Hub &

Spoke Design

Due to

Bottom-Up

design,

presumed

lagging if

present at all.

Poorly

documented

in research

papers

Confirmed as a

gap. Purpose

specific

approach to

individual data

flows. urgently

requires

attention

No evidence. AI

data

mining/processing

techniques

deployed on a

“black box” basis

Register

based,

legislatively

driven

approach

ensures

commonality

and consistent

with external

parties (banks

for eID

infrastructure)

Data Access/

Governance

Form/Governance

Mechanism

Access Risk

Assessment

Access

Protocols

Access

Logging/Control

Compliance &

Security

Varied,

complex and

diverse rules

Stringent

governance,

centrally

overseen

Stringent data

provenance,

sharing,

processing and

access controls;

Ethical, Research

and governance

sign off required

No central

oversight but

confirmed patient

opt-out

Strict

legislatively

defined

governance

Data Lifecycle/

Domain Scope

Data definition,

production,

retention,

retirement

Unspecified

in literature

Unspecified in

literature

Unspecified in

literature

Unspecified in

literature

Unspecified in

literature

Best Practice in Multi-organisation Sensitive Health Data Sharing: A Comparative Analysis of Ireland’s Data Governance Approach for the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub

65

He further noted the architecture of the Data Research

Hub establishes a foundation for potential future

expansion to the education and labour market, for

which there is demand for research purposes.

The interviewee identified that a lack of metadata

for data sets is an issue, as the CSO receives data from

the HSE directly from diverse systems, each of which

was designed independently, for diverse purposes.

Researchers rely on data sets that display consistency,

are complete and ready for research purposes.

Bridging this gap is a considerable challenge. In

particular, data access, metadata availability, and the

lack of a persistent identifier created issues. It was

also identified that reluctance to embrace standard

identifiers across the public sector is problematic. In

noting that the resistance existed even prior to GDPR

and the DPC, he also noted that ‘bravery’ is now

necessary, to galvanise the effort to mobilise

administrative data for public policy development.

As a general remark, it was noted that investment

in data which is based on sensors and IoT must be

considered. However, this area raises the challenge of

the sheer size of the data flows implying a need to

engage with partners, including potential outsourced

providers, which may imply cloud solutions for data

that is not sensitive. This would represent a

considerable departure for the public sector.

3.4 Discussion

From the above, we can draw a number of

conclusions: the stakeholder confirmed the growing

trend in Europe to make data available for research

purposes has reached Ireland, but noted the

difficulties that come alongside this in respect of

legislation that limits the use of health data for

research purposes. While these difficulties have been

discussed within scholarship and in papers outlining

other European health hub systems, (Winter and

Davidson , 2018) the author made it clear that these

were not considered for direct implementation.

Nonetheless, international trends were observed, as

noted in topic 2. Some of the international trends

observed, such as metadata (which also implies data

quality), data availability, legislation and consent

have been parts of data governance state-of-the-art

scholarship (K. C. O’Doherty et al, 2021), (Prainsack

& Buyx, 2013) (McMahon, Buyx & Prainsack, 2020),

(Cuggia & Combes, 2019). Despite the fact the

interviewee has not mentioned data governance

specifically as an influencing factor, this does not

imply that it cannot exist de facto. It should be further

noted that while data governance has been confirmed

to be an influencing success factor in prior

scholarship, (Panian, 2010) it is nonetheless not in the

mainstream yet. This is further exacerbated by the

fact that scholarship is only recently treading the

waters of data governance in international health

hubs. The interviewee, in topic 5, discussed the lack

of explicit consent for data as research assets.

Nonetheless, the interviewee interestingly mentions

the overriding public interest. Article 6(e) of the

GDPR does allow processing for the purposes of

performance of a task carried out in the public interest

(GDPR, 2018). The German Data Protection

Commission has recently approved a set of (updated)

forms used to ensure a provision for patient data for

medical research purposes (Virtuelles

Datenschutzbüro, 2021). They will be approved for

use by the Medical Informatics Initiative, which is

essentially, a data hub much like the Covid–19 Data

Research Hub developed by the HSE and CSO, with

the two diverging factors being that the German data

hub encompasses all medical data, as opposed to

Covid–19 related data, (MII Germany, 2021) and the

‘bottom-up’ approach taken by Germany, wherein a

consortia of hospitals, universities, and private

partners exists (Cuggia & Combes, 2019). The French

Health Data Hub, known as the ‘Plateforme nationale

des données de santé’, or HDH, is more similar to the

Irish hub, with the objective of promoting research.

Much like the Irish system, the French system was

also tested via pilot projects (“Plateforme des données

de santé, Direction de la recherche, des études, de

l’évaluation et des statistiques”, 2021). Furthermore,

the Irish system also features the employment of data

producers, as a joint venture by the HSE and CSO.

While the full comparisons between the data

governance of the French, Estonian, German, and

Irish data hubs would be extensive, our initial

research has nonetheless shown that the hubs differ

greatly. International comparisons do not play a role

in de facto application of development of health data

hubs, and this is mostly arising out of the factors

which necessitate the hub in the first place.

Conclusively, there seems to be general international

practice that simply occurs on the basis of best

practice reasoning. While international hubs were not

considered in respect of applicable features,

nonetheless, there is general international practice

used that can be found across all hubs.

4 CONCLUSION

While international Health Data Hubs exist or are in

development, they diverge as much as they intersect

as regards purpose, governance, and implementation.

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

66

Key areas of data governance development focus

should be made a priority, in particular in order to

preserve public confidence and to support future

interoperability and long-term utility from data

sources. In particular, attention should be paid to

consent and metadata management and to data subject

transparency.

The Covid–19 Data Research Hub is

distinguished in particular by the fact that it focuses

exclusively on public sector data being made

available to academic researchers for emergency

response purposes. International standard ethics

approval is required for research projects, consistent

with comparator models in the UK, France and

Germany. Due to the retrofitting of the data access

model to diverse available sources, preliminary

consent has had to be dispensed with, although a

robust retrospective process for consent management

is in place. Rigorous researcher access protocols are

applied, and the purpose of the research is firmly

focused on public good outcomes, thus in this respect

it appears to offer a particularly high level of

assurance to data subjects individually and

collectively.

All evidence suggests the CSO’s ingestion,

collation and preparation of data for research access,

via Research Micro-Data File access, complies with

rigorous data governance standards, protecting the

privacy of data subjects and limiting access strictly to

that which is necessary. There are no “black box”

processes and Data Subjects can access full

transparency details in respect of the processing

principles applied to their data. Outputs are rigorously

checked for Statistical Disclosure. No cloud

technology is used, and data is securely held on

premise at all times.

While transparency is well documented in

general, however, the Data Subject enjoys very

limited transparency at the individual level. This

aspect cannot easily be retrofitted to a system

developed reactively and drawing on disparate

sources, not designed for this purpose. This stands in

stark contrast, for example, to the Estonian Digital

Government model where a discrete Service Layer

(Winter and Davidson (2019) ensures Data Subjects

have real time visibility on the use of their data and

the X-Road based Data Registers model ensures that

any given variable has a single consistent, auditable

source. In order to preserve public confidence,

progress in this area is desirable.

At the statistical level, the absence of strong

semantic compatibility and inter-operability/meta-

data standardisation hampers data processing, making

the role of the CSO particularly challenging. Unique

identifiers would assist considerably, as would

common meta-data standards.

This research did not reveal ideal international

comparators against which to benchmark the Covid–

19 Data Research Hub, but general learnings were

nonetheless instructive in particular as regards

general pitfalls for large scale data sharing and

analysis. The lessons learned from Estonia offer a

particularly illuminating view of the possibility for

the safe, trusted and transparent use of public

administrative data “as a public asset” and these

should be studied in particular detail in the

perspective of future investment in Irish public sector

research capability. Benchmarking against academic

data governance models reveals key weaknesses, in

particular in respect of meta data and data lifecycle

management, while issues of Data Quality validations

are also ripe for further examination.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express a special thanks to Mr Paul

Morrin of the Central Statistics Office for his

assistance as part of this project. This research has

received funding from the ADAPT Centre for Digital

Content Technology, funded under the SFI Research

Centres Programme (Grant 13/RC/2106\_P2), co-

funded by the European Regional Development Fund.

For the purpose of Open Access, the author has

applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any

Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from

this submission.

REFERENCES

“Art. 6 GDPR – Lawfulness of processing,” General Data

Protection Regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-

info.eu/art-6-gdpr/ (accessed Apr. 16, 2021).

“Art. 9 GDPR – Processing of special categories of personal

data” General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

https://gdpr.eu/article-9-processing-special-categories-

of-personal-data-prohibited/

Abraham R., Brockeand J. V. & Schneider J., (2019) “Data

Governance: A Conceptual Framework, Structured

Review and Research Agenda” International Journal of

Information Management vol 49 pp424-438, Dec. 2019

doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.008

Cuggia M. & Combes S., ‘The French Data Hub and The

German Medical Informatics Initiatives: Two National

Projects to promote Data Sharing in Health Care’,

Yearb of Med Inform, vol 28, pp 195-202, Aug. 2019

DOI: 10.1055/s-0039-1677917.

Best Practice in Multi-organisation Sensitive Health Data Sharing: A Comparative Analysis of Ireland’s Data Governance Approach for the

Covid–19 Data Research Hub

67

DAMA International (2017). DAMA-DMBOK: Data

Management Body of Knowledge, Second Edition.

Bradley Beach, N.J.: Technics Publications, 2017.

De Prieëlle F., De Reuver M. & Rezaei J., (2020) “The

Role of Ecosystem Data Governance in Adoption of

Data Platforms by Internet-of-Things Data Providers:

Case of Dutch Horticulture Industry,” IEEE

Transactions on Engineering Management, vol 1, pp.

1–11, Jan. 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1109/

TEM.2020.2966024

e-Estonia.com ‘E-Health Records’, <https://e-estonia.com/

solutions/healthcare/e-health-record/> (accessed 13

March 2021); ‘Page d’accueil’, Health Data Hub.fr,

<https://www.health-data-hub.fr/> (accessed 13 March

2021); ‘Digital Medicine - BIH’, Berlin Institute of

Health.org, <https://www.bihealth.org/en/research/

translation-hubs/digital-medicine> (accessed 13 March

2021); ‘Our Hubs’, HDR UK.ac.uk <

https://www.hdruk.ac.uk/helping-with-health-data/our-

hubs-across-the-uk/> (accessed 13 March 2021.)

Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, High-Level Expert

Group on AI. This followed he publication of the

guidelines’ first draft in Dec 2018. https://digital-

strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-

trustworthy-ai

Golberg M. & Zins M., (2021) Le Health Data Hub (suite),

Med Sci (Paris) vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 271-276, Mar. 2021,

doi: https://doi.org/10.1051/medsci/2021016.

Hripcsak G. et al, (2014) “Health data use, stewardship, and

governance: ongoing gaps and challenges: a report from

AMIA’s 2012 Health Policy Meeting.” Journal of the

American Medical Informatics Association, vol.21,

pp.204-211, Mar. 2014, doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.11

36%2Famiajnl-2013-002117

Khatri V. & Brown C. V., (2010) ‘Designing Data

Governance’ Communications of the ACM vol 53, pp

148 - 152, Jan. 2010

Lis D. & Otto B., (2020) "Data Governance in Data

Ecosystems – Insights from Organizations" presented at

Americas Conference on Information Systems, 2020,

pp. 1-10, doi: https://www.researchgate.net/

publication/343215188_Data_Governance_in_Data_E

cosystems_-_Insights_from_Organizations

Margetts H. & Naumann A., 'Government as a platform:

What can Estonia show the world?’ Oxford Politics

Research Paper, 2017 <https://www.politics.ox.ac.uk/

publications/government-as-a-platform-what-can-

estonia-show-the-world.html

McBride K., Toots M., Kalvet T. & Krimmer R., (2018)

‘Leader in e-Government, Laggard in Open Data:

Exploring the Case of Estonia’, Reuve francaise

d’administration publique vol. 167 no 3 pp 613-625

https://www.cairn.info/revue-francaise-d-

administration-publique-2018-3-page-613.htm

McMahon A., Buyx A., & Prainsack B., (2020) “Big Data

Governance Needs More Collective Responsibility:

The Role of Harm Mitigation in the Governance of Data

Use in Medicine and Beyond,” Med. Law Rev., vol. 28,

no. 1, pp. 155–182, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.1093/

medlaw/fwz016

MII Germany, “About the initiative | Medical Informatics

Initiative.” https://www.medizininformatik-initiative.

de/en/about-initiative (accessed Apr. 16, 2021).

Nielsen, O.B., (2017) A Comprehensive Review of the Data

Governance Literature, Selected Papers of the IRIS no

8 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/301373908.pdf

Nissenbaum H., (2009) ‘Privacy in Context: Technology,

Policy and the Integrity of Social Life’, Stanford, CA,

USA Stanford University Press, 2009

O’Doherty K. C. et al (2021) “Toward better governance of

human genomic data,” Nat. Genet., vol. 53, no. 1, Art.

no. 1, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00742-6.

Panian Z., (2010) Some Practical Experiences in Data

Governance in World Academy of Science, Engineering

and Technology, doi: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/

viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.190.6948&rep=rep1&t

ype=pdf

Prainsack B. & Buyx A., (2013) “A Solidarity-Based

Approach to the Governance of Research Biobanks,”

Med. Law Rev., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 71–91, Mar. 2013,

doi: 10.1093/medlaw/fws040.

République Française, “Plateforme des données de santé |

Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et

des statistiques.” https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/

article/plateforme-des-donnees-de-sante (accessed

Apr. 16, 2021).

Sharma A., Borah S. B. & Moses A. C., (2021) ‘Responses

to Covid–19: The Role of Governance, Healthcare

Infrastructure, and Learning from Past Pandemics’

Journal of Business Research vol.122, pp. 597-607, Jan

2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.0

11.

Tse D., Chow C., Ly T., Tong C. & Tam K., (2018) ‘The

Challenges of Big Data Governance in Healthcare’, in

17th IEEE International Conference On Trust, Security

And Privacy In Computing And Communications/ 12th

IEEE International Conference On Big Data Science

And Engineering, 2018, pp.1632-1636, doi:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnu

mber=8456108.

Virtuelles Datenschutzbüro, “Datenschutzbehörden des

Bundes und der Länder akzeptieren die Einwilligungs-

dokumente der Medizininformatik-Initiative.”

https://www.datenschutz.de/datenschutzbehoerden-

des-bundes-und-der-laender-akzeptieren-die-

einwilligungsdokumente-der-medizininformatik-

initiative/ (accessed Apr. 16, 2021).

Wang Y., Kung L. & Byrd T., (2018) ‘Big Data Analytics

– Understanding Capabilities and Potential Benefits for

Healthcare Organisations’, Technology Forecasting

and Social Change vol 126, pp. 3-13, Jan. 2018 , doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.12.019

Winter J. S. & Davidson E., (2018) ‘Big Data Governance

of Personal Health Information and Challenges to

Contextual Integrity’ The Information Society vol 35,

pp 36 - 51, Dec. 2018, doi: https://doi.org/

10.1080/01972243.2018.1542648

HEALTHINF 2022 - 15th International Conference on Health Informatics

68