Happily Married in the Absence of a Child:

Marital Satisfaction of Voluntary and

Involuntary Childless Individuals

Mutiara Ramadhita Roesad

a

and Pingkan C. B. Rumondor

b

Department of Psychology, Bina Nusantara University, Kemanggisan Ilir III No. 45 Kemanggisan,

Palmerah, Jakarta, Indonesia

Keywords: Marital Satisfaction, Voluntary Childless, Involuntary Childless, Young Adult, Indonesia.

Abstract: The absence of a child due to involuntary reasons can create tension between wife and husband. In contrast,

the decision to be voluntary childless might not cause tension but could burden couples with social

expectations. In line with the vulnerability-stress-adaptation model, both processes can cause stress that

hinders marital satisfaction. This research aims to test the differences in marital satisfaction between

involuntary and voluntary childless groups. Using quantitative data collected via an online survey from 108

involuntary childless and 112 voluntary childless participants, mean differences for both groups were tested

with the Mann-Whitney method. The result obtained from the marital distress cut-off score based on the

Couple Satisfaction Index (CSI) showed that the marital satisfaction for both involuntary and voluntary

childless was relatively high, and there were no differences between the two groups. This research suggested

that participants in both groups (voluntary and involuntary childless) experienced relatively high marital

satisfaction despite the stress that they experienced. Further study regarding the adaptive process or dyadic

coping in childless couples is needed to understand how couples buffer the negative impact of stress on marital

satisfaction.

1 INTRODUCTION

"When will you get married?" is a common question

frequently asked to a young adult in Indonesia. In

Indonesia, when someone enters adulthood, they are

expected to form an intimate relationship and marry

their partner. After a person gets married, another

question will follow: "When will you have kids?".

Indeed, most couples will long for the presence of

children to complement their marriage. Moreover,

society seems to demand a presence of a child in the

newly formed family. However, expectations of

having children do not always go as expected, despite

various efforts made by the couple. The World

Health Organization (WHO) estimates that around

50-80 million married couples (1 in 7 couples) have

infertility problems. In Indonesia, infertility occurs in

more than 20% of the population, 40% in women,

40% in men, and 20% in both. As a consequence, the

family cannot have a child (Gina & Ircham, 2017).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3428-4139

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0778-929X

On the contrary, some couples willingly decided

to postpone pregnancy because they have many

considerations related to children. Data on Fertile

Age Couples (PUS) showed that many do not have

children among individuals in the age range of 20-35

years old (Wahyuni & Mahmudah, 2017). In addition,

according to the Ministry of Women's Empowerment

and Child Protection data, from 2018 to 2025, there

will be a decrease in the number of children

population as a result of decreased Total Fertility Rate

in Indonesia (Windiarto et al., 2019). Based on those

data, it can be assumed that adults in Indonesia are not

in a hurry to have children.

We surveyed reasons and stressors related to

childless conditions to 32 married individuals without

children, both voluntary and involuntary. Based on

the survey, 31.2% of participants voluntarily

postpone having a child. The reasons given were

various, such as "wanting to enjoy time with the

partner", "preparing financially and mentally",

438

Roesad, M. and Rumondor, P.

Happily Married in the Absence of a Child: Marital Satisfaction of Voluntary and Involuntary Childless Individuals.

DOI: 10.5220/0010753400003112

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences (ICE-HUMS 2021), pages 438-447

ISBN: 978-989-758-604-0

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

"delaying due to the COVID-19 condition", and

"feeling that children were not a priority in married

life". This condition puts pressure on the couple, as

illustrated by the mini-survey. The most frequently

mentioned pressures were "questions from extended

family" and "social pressure". Meanwhile, 68.8% of

couples wanted and were trying to have children.

Participants reported that some of the efforts were

"actively engaging in sexual activities without using

contraception" and "consulting with doctors".

Children are one of the essential factors in the

family because when forming a family, ideally, the

partner will desire the child's presence to complement

the family. Children could bring partners closer

together, and some couples reported greater closeness

due to having children (Twenge, Campbell, & Foster,

2003). However, not all married couples can have

children immediately. Couples who intend to have

children but are unable due to experiencing fertility

problems are called involuntary childless (Malik,

2021). Previous empirical data shows that more than

11% of women with infertility problems will have

lower self-confidence (Azizi, 2018). The decrease of

self-confidence is due to the role expectation for adult

women to be a mother.

As a pronatalist country,

married couples who do not have children after years

of marriage will be considered imperfect marriages

(Patnani, Takwin, & Mansoer, 2020). As a result,

several couples in Indonesia have made various efforts

to have children. Planning and trying to have children

can create tension in the marriage relationship,

reducing satisfaction in life (Onat & Beji, 2012).

Meanwhile, at the partner level, infertility causes

high tension and a tendency to blame each other

(Patnani et al., 2020). This disharmony can lead to new

conflicts that encourage couples to take divorce as a

way out to overcome guilt and failure (Onat & Beji,

2012). This finding is in line with several views

regarding marital satisfaction, which stated that

planning children could play an important role in

marital satisfaction (Bradbury, Fincham, & Beach,

2000).

Although it is stated that children are an essential

factor in relationships, some couples deliberately delay

having children. Couples who voluntarily do not intend

to have children even though they are of childbearing

age and condition are voluntary childless (Malik,

2021). The reasons given vary widely. Stegen,

Switsers, & Donder, (2021) summarize some of the

reasons couples delay having children. First, a person

may prefer to focus on career rather than family, so the

spouse does agree not to have children. Second, a

person may have a skeptical view of their social

environment and choose not to have children. Third,

some couples have external circumstances (such as

financial conditions) that cause permanent delays in

having children. When a couple does not plan to have

children, the marriage satisfaction obtained will be

different from involuntary childless couples because

the meaning of their married life will be more positive

(Maliki, 2019).

Marital satisfaction is an individual global

evaluation of marital relationships (Hinde, 1997). In

line with this definition, Rogge & Fincham (2010)

define marital satisfaction as a couple's subjective

evaluation of the romantic relationship. A higher

level of marital satisfaction is associated with lower

instability and divorce in a relationship (Falconier,

Jackson, Hilpert, & Bodenmann, 2015). Thus, marital

satisfaction is essential for couples to feel in

maintaining couples' harmony. In order to achieve

marital satisfaction, there are aspects of married life

that must be fulfilled include independent life,

attention and affection from partners, and the

presence of children (Mardiyan & Kustanti, 2016).

These aspects are a picture of the married life that the

couple wants to achieve. Previous research on marital

satisfaction of childless couples has focused more on

couples who are involuntarily childless. The results

obtained by previous research are that the absence of

children is one of the factors that affect marital

satisfaction (Mardiyan & Kustanti, 2016). However,

there are not necessarily the same results for couples

who do choose not to have children. Therefore, this

study describes marital satisfaction in couples who

are childless, voluntary, or involuntary.

Marital satisfaction does not occur spontaneously;

it requires the efforts of both partners. If both parties

have no effort, marital satisfaction can be unstable

and at significant risk (Azizi, 2018). According to

Azizi (2018), marital satisfaction is a personal

experience that can only be assessed from self-

pleasure due to the marriage relationship. Marital

satisfaction is also related to other people's

expectations, as it is considered necessary by the

social environment to have a successful marriage.

Various studies show different definitions of marital

satisfaction. Marital satisfaction can also be defined

as the extent to which married couples feel fulfilled

in their relationship (Rice, Stinnett, Stinnett, &

DeGenova, 2017).

According to Rogge & Fincham (2010), marital

satisfaction is a subjective evaluation of the couple's

current romantic relationship. In line with this, Funk

and Rogge (2007) define marriage satisfaction as an

individual's subjective assessment of their marriage.

In addition, marital satisfaction can also be defined as

an overall assessment of the current partner's

Happily Married in the Absence of a Child: Marital Satisfaction of Voluntary and Involuntary Childless Individuals

439

romantic relationship and is influenced by many

specific factors (Azizi, 2018). The definition of

marriage satisfaction that will be used in this study is

based on Funk & Rogge (2007), marital satisfaction

is an individual assessment of their marriage which is

subjective. Both parties need to feel happiness and

satisfaction by respecting each other to achieve a

harmonious marriage (Mardiyan & Kustanti, 2016).

Factors that can be used to measure marital

satisfaction include communication, recreational

activities, religious orientation, problem-solving,

financial management, sexual orientation, family and

friends, children and parenting, personality problems,

as well as equality of roles (Fowers & Olson, 1993).

However, this study reviews the factors that influence

marriage satisfaction based on the vulnerability-

stress-adaptation model (VSA).

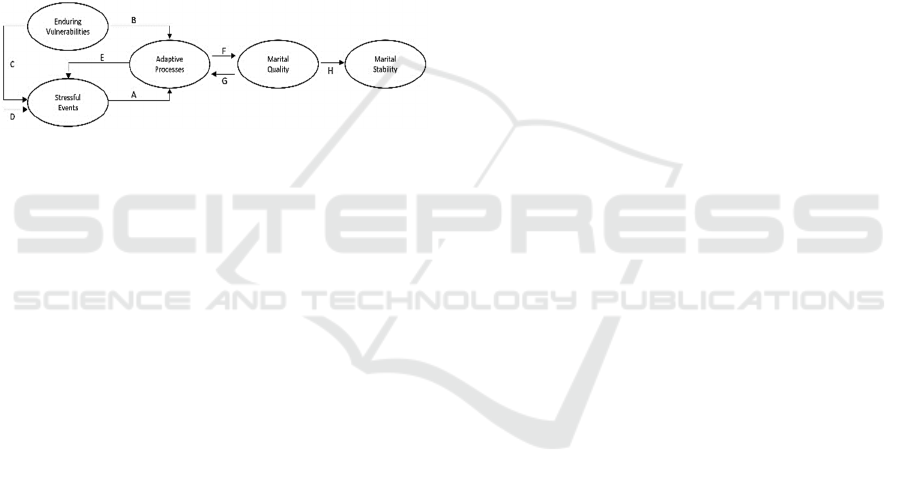

Figure 1: Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA) Model.

The Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation (VSA)

model provides a framework for explaining how

marriage changes over time (Karney & Bradbury,

1995). According to the VSA model in Figure 1,

individuals carry pre-existing vulnerabilities into

their marriage (i.e., personality) or experience factors

(i.e., parental divorce). In addition, marriage is also

affected by stressful events (i.e., financial, chronic

illness, and the presence of children). In the end, the

couple will try to adapt to the partner in response to

stress and is conceptualized as an exchange of

positive or negative behavior (Langer, Lawrence, &

Barry, 2008).

The first factor is vulnerability. Vulnerability is a

stable characteristic that every couple brings into

marriage (Aditya & Magno, 2011). Vulnerability

includes a person's character, personality, family

background, level of education. Voluntarily childless

couples do not intend to have children (Peterson,

2015), while involuntarily childless have the intention

and desire to have children but cannot due to a

specific condition (Van Balen & Trimbos-Kemper,

1995). The differences in motivation usually come

from a person's background, such as family

background, educational background, and personality

(Veevers, 1979). These differences in motivation

resulting in different views on the stressful events felt

by the partner. Involuntarily childless couples

experience a higher level of depression, lower

happiness, and life satisfaction than the voluntarily

childless couples (Jeffries & Konnert, 2002). In

addition, many couples tend to impose behavioral

characteristics on their partners, so this personality

can become a stressor in their marital relationship

(Sayehmiri, Kareem, Abdi, Dalvand, & Gheshlagh,

2020). One personality trait that has a significant

influence on marital relationships is neuroticism

(Piedmont, 1998). Neuroticism refers to a person's

tendency to feel anxiety, making a person easily feel

stressed in challenging situations.

Unfulfilled expectations can harm the partner and

can be seen as a stressful event. Stressful events are

developmental transitions, situations, events, and

chronic states experienced by both parties that make

the partner depressed (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). In

this study, these stress factors will be focused on

factors of children's absence, whether voluntary or

not. Couples who experience infertility include

experiencing emptiness, fatigue, frustration, anxiety,

lower personal well-being, lower happiness, and life

satisfaction and are considered bad luck (Patnani et

al., 2020). Conflicts like this can cause tension in the

couple. When the expectation of having children is

not fulfilled in involuntarily childless couples, there

will be high tension and a tendency to blame each

other (Patnani et al., 2020). Meanwhile, for

voluntarily childless couples, women can get an

opposing view from society, such as selfishness, lead

an unsatisfactory life, unhappy marriages, less

happiness in general, irresponsibility, and disorders

(Kelly, 2009). In the VSA model, the experience of

childlessness (both voluntary and involuntary) can be

seen as stressors because that situation can make both

partners feel stressed.

This stressful situation will encourage the couple

to solve the problems at hand. This push will make

the pair enter into the third factor of the VSA model,

namely the adaptation process. The adaptation

process is a way for couples to treat and respond to

each other to resolve the problems in marriage

(Aditya & Magno, 2011). Involuntary childless

couples will try to compromise the unfulfilled

expectations and find a way out of comments from

their society and their thoughts to avoid conflicts in

the household. Meanwhile, voluntary childless

couples will try to find a way out of the negative

comments received from their society. Therefore, the

researcher assumes low marriage satisfaction occurs

in involuntarily childless couples because their

problems come from the external environment and

the couple themselves due to unfulfilled expectations.

On the other hand, voluntarily childless couples

suffer from negative comments from their

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

440

environment, but couples have the same motivation

not to have children. The difference in stress levels

felt by the two groups led the researchers to assume a

higher marriage satisfaction occurred in voluntarily

childless couples.

This study will describe stressors caused by a

child's absence and relationship quality, measured

using the couple satisfaction index (CSI-16). The

absence of a child can be a stressor for couples

because, in Indonesia, the presence of children is an

ideal picture of a family. Moreover, marital

satisfaction is an essential predictor of a person's

well-being and health. High marital satisfaction can

positively impact marital stability and subjective

well-being (Margelisch, Schneewind, Violette, &

Perrig-Chiello, 2017). Conversely, low marital

satisfaction can harm subjective well-being (Proulx,

Helms, & Buehler, 2007). Therefore, for childless

couples, stress and marital satisfaction can impact

individuals' and couples' live.

Several previous studies, including both sexes,

have shown that the psychological response to

infertility is different for men and women (Schanz et

al., 2005). The stigma formed by the social

environment in unborn couples often affects a

person's mental health, especially women (Tanaka &

Johnson, 2014). Meanwhile, men appear to

experience less psychological stress than women

(Schanz et al., 2005). Previous empirical studies have

shown that childless individuals will have more time

for themselves (Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003).

Moreover, Nachtigall, Becker, and Wozny (1992)

concluded that failure to fulfill maternal roles

negatively affects women's perceptions of themselves

and thus experiences emptiness. Frustration and

anxiety can also be experienced by individuals who

have not had children because the social pressures

exhibit negative stigma, such as being selfish or not

trying hard enough to have children (Patnani et al.,

2020). In addition, individuals who do not have

children are often considered to have deviated from

the normative way of life and become a cause of stress

relevant to identity (Tanaka & Johnson, 2014).

A partner's experience without childcare can have

both positive and negative effects. The absence of

children can support couples to have more time

together and do activities that most parents cannot do

(Patnani et al., 2020). Financially, couples also do not

have the responsibility to meet children's needs. Thus

they can save more and used the finance for their own

needs, resulting in more satisfaction with their

financial condition (Patnani et al., 2020). In couples

who experience infertility, this problem can cause

new conflicts and tension because children's planning

can play an important role in marriage satisfaction

(King, 2016).

In the literature, researchers generally distinguish

between "voluntarily" and "involuntarily" childless.

This difference is based on the couple's motivation

not to have children (Veevers, 1979). In addition, this

difference is often used to distinguish between

biological reasons and other reasons for not having

children (Kreyenfeld & Konietzka, 2016). Women

who voluntarily do not have children are called

voluntarily childless. Peterson (2015) defines

voluntary childless as someone without biological

children who does not expect anything in the future

and intends or chooses not to have children. In

defining voluntarily childless in someone, (Veevers,

1979) states that several things need to be considered.

First, the partner's intentions for the future must be

ascertained. Even though the couple has not had

children at a particular time, this may only be

temporary for some people. Some couples usually

postpone the arrival of children until the time they

feel is appropriate, rather than permanently childless.

The second thing to note is commitment. Couples

need to identify a commitment to the intention not to

have children, whether that commitment is high or

low. The choice and commitment of partners to

voluntarily not have children is often seen as deviant

and experiences adverse reactions from people who

do not see them as "normal" (Thole, 2018).

Voluntarily childless individuals often accept this

adverse reaction, especially for women. (Kelly, 2009)

provides several negative views that voluntarily

childless women experienced: being selfish, living an

unsatisfactory life, unhappy marriages, generally less

happy, irresponsible, and abnormalities.

In contrast to voluntarily childless, when a partner

has the intention to have children but is unable due to

certain conditions, such as infertility, the partner is

called involuntarily childless (Van Balen & Trimbos-

Kemper, 1995). Infertility is a condition where there

is no conception after having repeated sexual

intercourse for 12 months or more and without using

protective equipment (Jeffries & Konnert, 2002). In

Indonesia, it is estimated that the number of couples

with infertility problems ranges from 10-15% of the

total average population (Patnani et al., 2020).

Cultural norms still require women to become

mothers, as people in Indonesia perceived having

children as a social identity (Hidayah, 2007). The

social impact experienced by involuntary childless is

usually worse than voluntary childless because of

pressure from the community, especially in

pronatalist countries, which strongly encourage birth

(Patnani et al., 2020). Difficulty having children

Happily Married in the Absence of a Child: Marital Satisfaction of Voluntary and Involuntary Childless Individuals

441

creates new conflicts that make couples blame each

other for the failures they face (Onat & Beji, 2012).

This kind of conflict makes involuntary childless

couples tend to have lower marital satisfaction.

This study aims to test marital satisfaction

differences in the voluntary and involuntary childless

couples in Indonesia, in their fertile age (20-35 years

old), and have been married for at least one year. In

order to screen voluntary and involuntary childless,

we asked their intention to have children. Participants

who were not intended to have children were

considered voluntarily, and participants who intended

to have children were considered involuntary

childless. In addition, this study also aims to describe

stressors experienced by both childless groups.

2 METHODS

This study uses a quantitative descriptive approach

and uses the Mann-Whitney test to test marital

satisfaction mean differences between the two groups

(voluntary and involuntary childless). This study was

conducted as a part of an undergraduate thesis and

have approved by the Research Ethics Committee of

the Department of Psychology, University of Bina

Nusantara. Participants were asked to fill a written

informed consent before filling the survey.

2.1 Participants

In this study, 220 participants were divided into 108

participants in the involuntary childless group and

112 participants in the voluntary childless group.

Further description of participant's demographics and

characteristics are described in the result section.

2.2 Materials

The instrument used to measure marital satisfaction is

the Couple Satisfaction Index (CSI-16) developed by

(Funk & Rogge, 2007) and have adapted to Bahasa

Indonesia (Putri, 2019). CSI (16) consists of 16 items

and uses a Likert scale to answer the questions given.

The total score is used for further analysis. In (Putri,

2019), CSI (16) was valid and reliable with the

coefficient alpha value of 0.898.

2.3 Procedures

This research was conducted by distributing

questionnaires online using Google Form and getting a

total of 220 participants who matched the

characteristics of the study. Questionnaires were

distributed from mid-December 2020 to early January

2021. The results obtained from the questionnaire were

then processed using the Mann-Whitney test using the

SPSS application to calculate the mean and mode of

marriage satisfaction for two groups of child absence,

namely voluntarily childless and involuntary childless.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Result

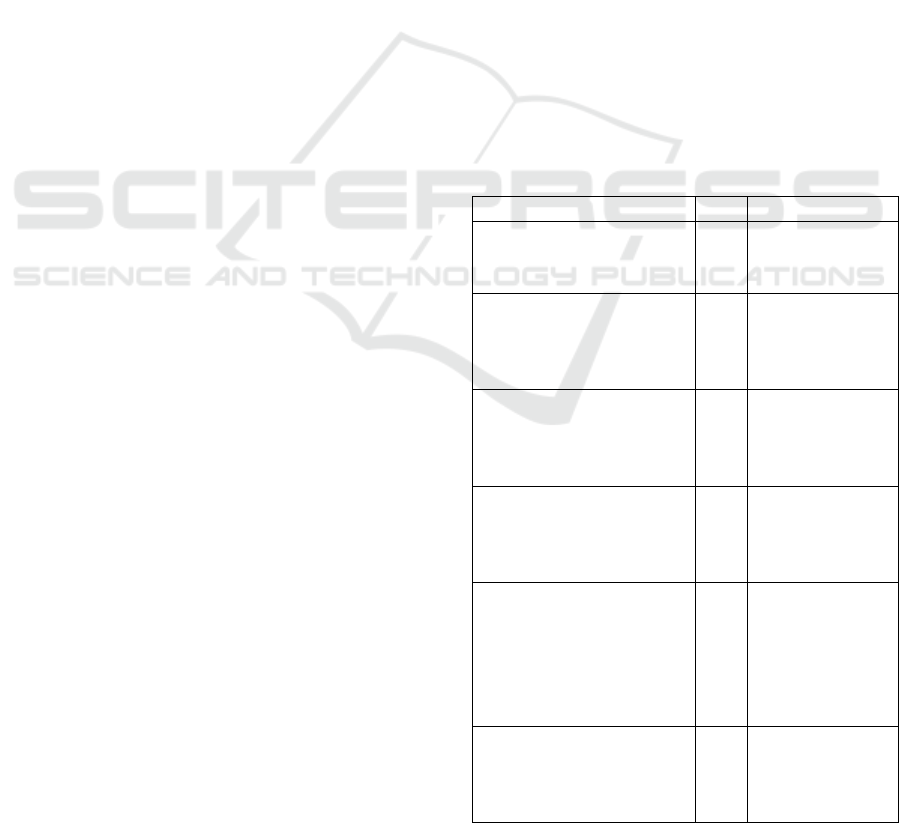

Based on data collection, demographic figures were

obtained for the two groups. In the involuntary

childless group (Table 1), most participants were

women (77.8%) and have been married for less than

Most participants are domiciled in Jabodetabek

(58.3%), while the rest come from outside

Jabodetabek with various cities in Indonesia. The

participants' education is quite diverse, ranging from

high school to master's degree, but 79.6% have

University (S1) backgrounds. Some participants have

had experiences of pregnancy (18.5%).

Table 1: Involuntary childless demographic.

Characteristics n Percentage (%)

Intention to have a child

Yes

108

100%

Total 108 100%

Gender

Men

24

22.2%

Women

84

77.8%

Total 108 100.0%

Marriage age

1-5 years

103

95.3%

>6 years

5

4.7%

Total 108 100%

Domiciled

Jabodetabek

63

58.3%

Outside Jabodetabek

45

41.7%

Total 108 100%

Education

High school

6

5.6%

Diploma

3

2.8%

S1

86

79.6%

S2

13

12.0%

Total 108 100%

Experiences of pregnancy

Yes

20

18.5%

No

88

81.5%

Total 108 100%

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

442

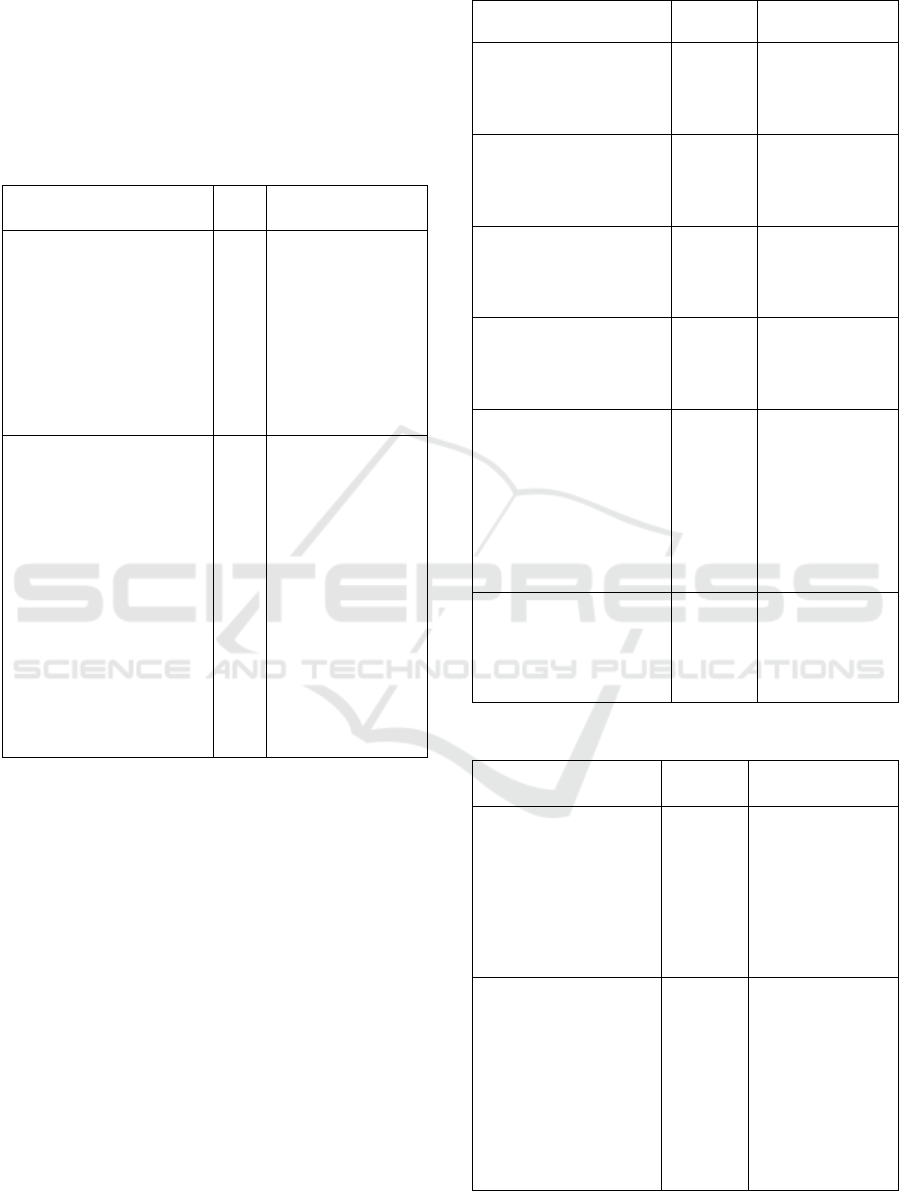

The condition of not having children involuntarily

turned out to impact the partner. As many as 73.2%

of participants felt stressed about this condition

(Table 2). The reasons for the pressure felt were

varied, but the majority came from within the

participants. As many as 50% of participants felt

stressed and had reduced self-confidence.

Table 2: Involuntary childless stress level and stressors.

Stress and Stressors n Percentage (%)

Stress level

Not stressed at all

11 10.2%

A bit stressed

18 16.7%

Stressed

46 42.6%

Very stressed

33 30.6%

Total 108 100%

Stressors

General stress

29 26.9%

Pressure from

p

arents/famil

y

18 16.7%

Other social pressure

15 13.9%

Descreased self-confident

25 23.1%

Both pressure from

family and social

3 2.8%

No stressors

13 12.0%

Others

5 4.6%

Total 108 100%

As for the voluntary childless group (Table 3),

there were 67 participants (59.8%) who had no

intention of having children and 45 (40.2%)

participants who still did not know whether they

wanted to have children or not. The participants in the

voluntary childless group majority were women

(91%). Most participants in this group have been

married for 1-5 years (91.9%), residing in Greater

Jakarta (55.4%), and have undergraduate education

(58.9%).

Moreover, all participants in the voluntary

childless did not have pregnancy experience.

Unlike the involuntary childless group, the

voluntary childless group condition of not having

children did not affect the level of stress felt by the

participants (Table 4). The majority of the sources of

pressure that were felt came from parents/family and

their social environment (75%).

Table 3: Voluntary childless demographic.

Characteristics n Percentage

(%)

Intention to have a child

No 67 59.8%

Haven’t decided 45 40.2

Total 112 100%

Gender

Men 10 9%

Women 102 91%

Total 112 100.0%

Marriage age

1-5 years 103 91.9%

>6 years 9 8.1%

Total 112 100%

Domiciled

Jabodetabek 62 55.4%

Outside Jabodetabek 50 44.6%

Total 112 100%

Education

Middle school 1 0.9%

High school 4 3.6%

Diploma 9 8.0%

S1 66 58.9%

S2 31 27.7%

S3 1 0.9%

Total 112 100%

Experiences of

p

regnanc

y

Yes 12 10.7%

No 100 89.3%

Total 112 100.0%

Table 4: Voluntary childless stress level and stressors.

Stress and Stressors n Percentage (%)

Stress Level

Not stressed at all

33 29.5%

A bit stressed

50 44.6%

Stressed

26 23.2%

Very stressed

3 2.7%

Total

112 100%

Stressors

General stress

3 2.7%

Pressure from

p

arents/famil

y

45 40.2%

Other social pressure

39 34.8%

No stressors

19 17.0%

Others

6 5.4%

Total

112 100%

Happily Married in the Absence of a Child: Marital Satisfaction of Voluntary and Involuntary Childless Individuals

443

Researchers then conducted a normality test for

Lilliefors (Kolmogorov Smirnov) because the data

used was > 50 respondents, and the value indicates

that the data is not normally distributed. Thus, the

hypothesis is performed using non-parametric

statistical tests. A Mann-Whitney test indicated that

marital satisfaction was greater for the voluntary

childless group (Mean = 78.77) than for the

involuntary childless group (Mean = 77.03).

However, the differences was not significant, U =

5253.500 (p = 0.092).

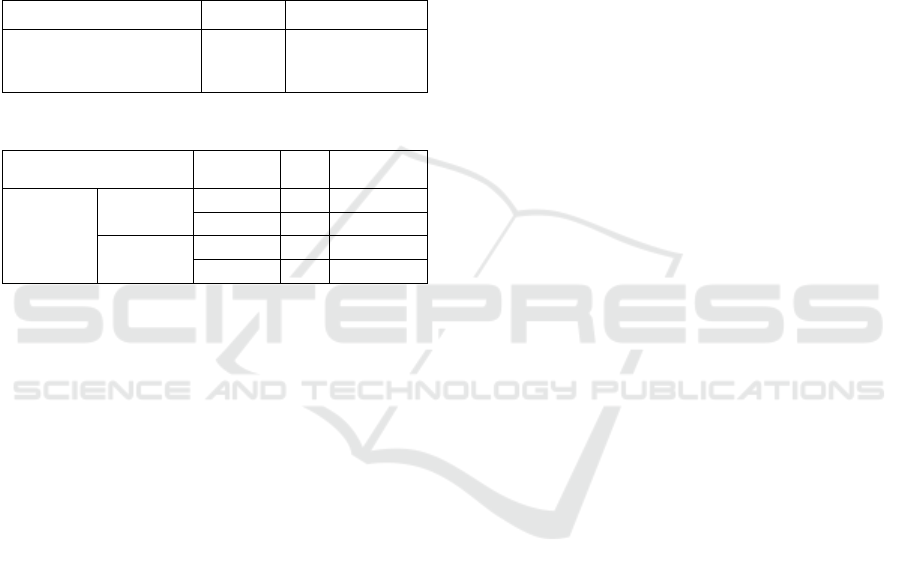

Table 5: Marital satisfaction mean.

n Mean

Involuntary Childless 108 77.03

Voluntar

y

Childless 112 78.77

Total 220 77.91

Table 6: Marital satisfaction distress cut score.

Distress

cut score

n

Persentase

(%)

Marital

satisfaction

Involuntary

<51.5 7 6.4%

>51.5 101 93.6%

Voluntary

<51.5 8 7.2%

>51.5 104 92.8%

Based on CSI 16, the distress cut score of marital

satisfaction is 51.5, which means that if the resulting

value is above 51.5, then participants have high

marital satisfaction. In the involuntary childless

group, the mean results of marriage satisfaction from

participants are 77.03, and in the voluntary childless

group, the mean result of marital satisfaction was

78.77. Thus, it can be concluded that the two groups

have relatively high marriage satisfaction.

3.2 Discussion

This study tests marital satisfaction differences

between voluntary and involuntary childless couples

in Indonesia in their fertile age (20-35 years old). The

Mann-Whitney test showed no difference in marital

satisfaction in the involuntary childless and voluntary

childless groups. Moreover, descriptive statistical

analysis results showed that the mean value of marital

satisfaction in the involuntary childless and voluntary

childless groups was above the distress cut score of

51.5. In the involuntary childless group, the mean

score was 77.03, and in the voluntary childless group,

the mean score was 78.77, and the overall group

average score was 77.91. These findings suggest that

marital satisfaction in the involuntary childless and

voluntary childless groups is relatively high.

Indeed, no research directly compares the

marriage satisfaction of involuntary childless and

voluntary childless in Indonesia. However, (Patnani

et al., 2020) research illustrates that couples

involuntary childless have experiences that vary from

positive to negative. The positive experiences felt by

couples in the involuntary childless group include

more time spent with partners than couples who

already have children so that they have the

opportunity to build more relationships with their

partners (Patnani et al., 2020). In involuntary

childless couples, they experience negative feelings

such as sadness, disappointment, failure, feelings of

guilt, and lack of confidence (Patnani et al., 2020).

According to Gold (2013) and Tanaka & Johnson,

(2014) research, this worse experience will be felt by

an involuntary childless couple who live in pro-natal

states. In line with the results of these two studies, this

study showed that 73.2% of participants in the group

involuntary childless felt depressed and very

depressed with the childless condition. The forms of

pressure that are felt include stress and lack of self-

confidence. Thus, the pressure felt by involuntary

childless couples makes most participants feel

stressed and less confident.

Unlike involuntary childless couples, couples in

the voluntary childless group perceived that majority

of the pressure that the participants' pressure came

from their family and social environment. Similarly,

(Matthews & Desjardins, 2016) found that the social

pressure of pronatalists makes the voluntary childless

couple feel frustrated and disappointed by the

judgments given by family, friends, health

professionals on their decision not to become parents.

However, the data in this study showed that only

25.9% of the participants indicated that they felt

stressed and very stressed over the choice of not

having children. This number was far less than the

involuntary childless group because there were 73.2%

who felt stressed and very stressed with the condition

of not having children. The description of the stress

level felt by the two groups made the researchers

assume that the marital satisfaction in the involuntary

childless group would be lower than the voluntary

childless group because the involuntary childless

couples had a higher level of stress.

Stressful experience is one of the factors of the

VSA model (Karney & Bradbury, 1995). The stress

felt by involuntary childless couples is different from

that felt by voluntary childless couples. In involuntary

childless, they feel that this condition represents a

kind of failure (Lampman & Dowling-Guyer, 1995)

because of an unfulfilled self-expectation that can

make couples feel depressed. In contrast, the

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

444

voluntary childless group’s choice not to have

children is often seen as deviant and experiences

adverse reactions from people who do not see them as

"normal" (Thole, 2018). Similarly, this study found

that pressure felt by this group resulted from external

factors. Thus, being in the childless marriage

voluntary leads to stressful experiences because of

how their external factor reacted. In other words,

voluntary childless group experience external stress

(Randall & Bodenmann, 2017).

When couples feel a stressful situation, this will

encourage couples to solve the problems they face.

The drive to solve these problems is the third factor

of VSA, namely the adaptation process (Karney &

Bradbury, 1995). One of the adaptation processes that

a couple can do is dyadic coping. Dyadic coping is a

multidimensional construct, including

communication and solving problems together,

giving and getting emotional support, and dealing

with changes and difficulties more as a couple than

two individuals (Gana, Saada, Broc, Koleck, &

Untas, 2017). According to Chaves, Canavarro, and

Moura-Ramos (2019), how couples perceive stress

signals shown by other partners (stress

communication), partner reactions, and how to deal

with them together can affect dyadic coping.

Therefore, it is possible that dyadic coping can help

couples cope with stressful conditions faced by their

partners.

The dyadic coping process can explain why there

is no difference in marital satisfaction in the

involuntary childless and voluntary childless groups.

Researchers assume that participants in this study

have adapted to stressful conditions that arise in

relationships. Thus, although participants in the

involuntary childless group had higher stress levels

than the voluntary childless group, they still had a

relatively high level of marital satisfaction. Likewise,

regardless of their stressful conditions, the voluntary

childless group also still has high marital satisfaction.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This study found no significant difference in marital

satisfaction of involuntary and voluntary childless

individuals. Moreover, both groups have relatively

high marital satisfaction, despite the stressors they

experienced. This study also found that both groups

have different stressors. The involuntary childless

experienced more stress from outside their

relationship (i.e., pressure from parents/family) than

general stress. However, most participants of this

study are women, and the result can not be

generalized to a larger male population. Thus, further

research could include a more balanced gender (i.e.,

a similar number of men and women) so that

participants are not dominated by one gender or are

more focused on one gender only.

Further research is also suggested to add other

variables such as dyadic coping to understand how

couples cope with external stress related to the

childless condition. Moreover, further research can

measure social desirability to control bias in the

results of marital satisfaction. In addition, further

research can also use measuring tools that support the

complete VSA model, such as personality measures

(i.e., big five inventory), stress (i.e., perceived stress

scale), and dyadic coping (i.e., dyadic coping

inventory).

REFERENCES

Aditya, Y., & Magno, C. (2011). Factors influencing

marital satisfaction among Christian couples in

Indonesia : A Vulnerability- Stress-Adaptation Model.

The International Journal of Research and Review,

7(2), 11–32.

Azizi, A. (2018). Regulation of emotional, marital

satisfaction and marital lifestyle of fertile and infertile.

Review of European Studies, 10(1), 14.

https://doi.org/10.5539/res.v10n1p14

Bradbury, T. N., Fincham, F. D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2000).

Research on the nature and determinants of marital

satisfaction: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage

and Family, 62(November), 964–980. https://doi.org/

10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00964.x

Chaves, C., Canavarro, M. C., & Moura-Ramos, M. (2019).

The role of dyadic coping on the marital and emotional

adjustment of couples with infertility. Family Process,

58(2), 509–523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/

famp.12364

Falconier, M. K., Jackson, J. B., Hilpert, P., & Bodenmann,

G. (2015). Dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction:

A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 28–

46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.002

Fowers, B. J., & Olson, D. H. (1993). Enrich marital

satisfaction scale: A brief research and clinical tool.

Journal of Family Psychology, 7(2), 176–185.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.176

Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with

item response theory: Increasing precision of

measurement for relationship satisfaction with the

Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family

Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/

0893-3200.21.4.572

Gana, K., Saada, Y., Broc, G., Koleck, M., & Untas, A.

(2017). Dyadic cross-sectional associations between

depressive mood, relationship satisfaction, and

common dyadic coping. Marriage and Family Review,

53(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2016.1247759

Happily Married in the Absence of a Child: Marital Satisfaction of Voluntary and Involuntary Childless Individuals

445

Gina, F., & Ircham, M. (2017). Pengaruh Keputihan

Patologi pada Wanita usia Subur (WUS) terhadap

Infertilitas Primer di RS Kia Sadewa Caturtunggal

Sleman Yogyakarta. Yogyakarta: Unpublished

Manuscript.

Gold, J. M. (2013). The experiences of childfree and

childless couples in a pronatalistic society: Implications

for family counselors. The Family Journal, 21(2), 223–

229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807

12468264

Hidayah N. (2007). Identifikasi dan pengelolaan stres

infertilitas. Humanitas, 4(1), 25–33.

Hinde, R. A. (1997). Relationships a dialectical

perspective. New York: Psychology Press.

Jeffries, S., & Konnert, C. (2002). Regret and psychological

well-being among voluntarily and involuntarily

childless women and mothers. International Journal of

Aging & Human Development, 54(2), 89–106.

https://doi.org/10.2190/J08N-VBVG-6PXM-0TTN

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal

course of marital quality and stability: A review of

theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin,

118(1), 3–34. doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-

2909.118.1.3

Kelly, M. (2009). Women’s voluntary childlessness: A

radical rejection of motherhood? Women’s Studies

Quarterly, 37(3/4), 157–172.

King, M. E. (2016, March). Marital satisfaction.

Encyclopedia of Family Studies, pp. 1–2.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119085621.wbefs054

Kreyenfeld, M., & Konietzka, D. (2016). Childlessness in

Europe: An overview. In M. Kreyenfeld & D.

Konietzka (Eds.), Childlessness in Europe: Contexts,

causes, and consequences (pp. 3–16). Cham: Springer

Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7

Lampman, C., & Dowling-Guyer, S. (1995). Attitudes

toward voluntary and involuntary childlessness. Basic

and Applied Social Psychology, 17(1–2), 213–222.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.1995.9646140

Langer, A., Lawrence, E., & Barry, R. A. (2008). Using a

vulnerability-stress-adaptation framework to predict

physical aggression trajectories in newlywed marriage.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5),

756–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013254

Malik, S. A. (2021). Emotional competence and marital

adjustment among childless women. International

Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 74–78.

https://doi.org/10.30491/IJBS.2021.250640.1382

Maliki, A. R. (2019). Kesejahteraan subjektif dan kepuasan

perkawinan pada pasangan yang tidak memiliki anak

karena infertilitas. Psikoborneo, 7(4), 566–572.

Mardiyan, R., & Kustanti, E. R. (2016). Kepuasan

pernikahan pada pasangan yang belum memiliki

keturunan. Empati, 5(3), 558–565.

Margelisch, K., Schneewind, K. A., Violette, J., & Perrig-

Chiello, P. (2017). Marital stability, satisfaction and

well-being in old age: Variability and continuity in

long-term continuously married older persons.

Aging & Mental Health, 21(4), 389–398.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1102197

Matthews, E. J., & Desjardins, M. (2016). Remaking our

identities: Couples’ experiences of voluntary

childlessness. The Family Journal, 25(1), 31–39.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480716679643

Nachtigall, R. D., Becker, G., & Wozny, M. (1992). The

effects of gender-specific diagnosis on men’s and

women’s response to infertility. Fertility and Sterility,

57(1), 113–121.

Nomaguchi, K. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2003). Costs and

rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent

on adults’ lives. Journal of Marriage and Family,

65(2), 356–374.

Onat, G., & Beji, N. K. (2012). Marital relationship and

quality of life among couples with infertility. Sexuality

and Disability, 30(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/

s11195-011-9233-5

Patnani, M., Takwin, B., & Mansoer, W. W. (2020). The

lived experience of involuntary Cchildless in Indonesia:

Phenomenological analysis. Journal of Educational,

Health and Community Psychology, 9(2), 166–183.

https://doi.org/10.12928/jehcp.v9i2.15797

Peterson, H. (2015). Fifty shades of freedom. Voluntary

childlessness as women’s ultimate liberation. Women’s

Studies International Forum, 53, 182–191.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.10.017

Piedmont, R. L. (1998). The revised NEO personality

inventory: Clinical and research applications. In The

revised NEO Personality Inventory: Clinical and

research applications. New York, NY, US: Plenum

Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-3588-5

Proulx, C. M., Helms, H. M., & Buehler, C. (2007). Marital

quality and personal well-being. Journal of Marriage

and Familly, 69(August), 576–593.

Putri, D. A. (2019). Hubungan kepuasan pernikahan dan

dyadic coping pada orang tua dari anak dengan

spektrum autisme. Universitas Indonesia.

Randall, A. K., & Bodenmann, G. (2017). Stress and its

associations with relationship satisfaction. Current

Opinion in Psychology, 13, 96–106.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.010

Rice, F. P., Stinnett, N., Stinnett, N. M., & DeGenova, M.

K. (2017). Intimate Relationships, Marriages, and

Families. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rogge, R., & Fincham. (2010). Understanding relationship

quality: Theoretical challenges and new tools for

assessment. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 2,

227–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00

059.x

Sayehmiri, K., Kareem, K. I., Abdi, K., Dalvand, S., &

Gheshlagh, R. G. (2020). The relationship between

personality traits and marital satisfaction: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 15.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-0383-z

Schanz, S., Baeckert-Sifeddine, I. T., Braeunlich, C.,

Collins, S. E., Batra, A., Gebert, S., Fierlbeck, G.

(2005). A new quality-of-life measure for men

experiencing involuntary childlessness. Human

Reproduction (Oxford, England), 20(10), 2858–2865.

https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dei127

Stegen, H., Switsers, L., & Donder, L. De. (2021). Life

ICE-HUMS 2021 - International Conference on Emerging Issues in Humanity Studies and Social Sciences

446

stories of voluntarily childless older people: A

retrospective view on their reasons and experiences.

Journal of Family Issues, 42(7), 1536–1558.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X20949906

Tanaka, K., & Johnson, N. E. (2014). Childlessness and

mental well-being in a global context.

Journal of Family Issues, 37(8), 1027–1045.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14526393

Thole, M. M. (2018). “I am just as normal as they are”:

Reconstructing the definition of womanhood through

the experiences of voluntary childless women (Utrecht

University). Utrecht University. Retrieved from

http://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/365051

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Foster, C. A. (2003).

Parenthood and marital satisfaction: A meta- analytic

review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(3), 574–

583.

Van Balen, F., & Trimbos-Kemper, T. C. (1995).

Involuntarily childless couples: Their desire to have

children and their motives. Journal of Psychosomatic

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 16(3), 137–144.

https://doi.org/10.3109/01674829509024462

Veevers, J. E. (1979). Voluntary childlessness: A review of

issues and evidence. Marriage \& Family Review, 2(2),

1–26. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v02n02\_01

Wahyuni, C., & Mahmudah, S. (2017). Analisis sikap

pasangan usia subur tentang kesehatan reproduksi

terhadap penundaan kehamilan di Kelurahan Blabak

Kecamatan Pesantren Kota Kediri. Strada Jurnal

Ilmiah Kesehatan, 6(2), 59–62.

Windiarto, T., Yusuf, A. H., Nugroho, S., Latifah, S., Solih,

R., & Hermawati, F. (2019). Profil anak Indonesia

Tahun 2019. Jakarta: Kementerian Pemerdayaan

Perempuan dan Perlindungan Anak.

Happily Married in the Absence of a Child: Marital Satisfaction of Voluntary and Involuntary Childless Individuals

447